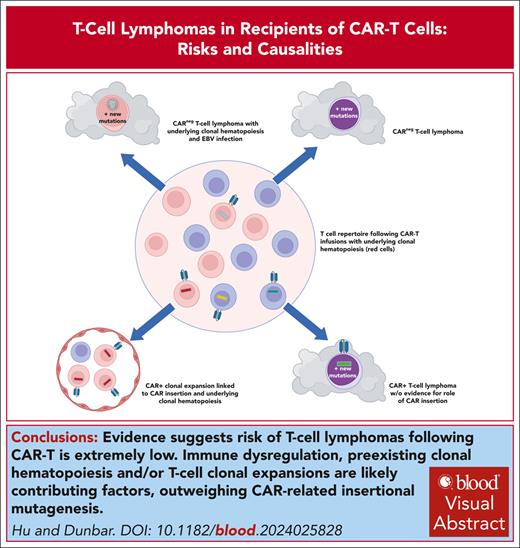

Visual Abstract

The US Food and Drug Administration announcement in November 2023 regarding reports of the occurrence of secondary T-cell lymphomas in patients receiving chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-Ts) for B-cell malignancies resulted in widespread concern among patients, clinicians, and scientists. Little information relevant to assessing causality, most importantly whether CAR retroviral or lentiviral vector genomic insertions contribute to oncogenesis, was initially available. However, since that time, several publications have provided clinical and molecular details on 3 cases showing clonal CAR vector insertions in tumor cells but without firm evidence these insertions played any role in oncogenic transformation. In addition, several other cases have been reported without vector detected in tumor cells. In addition, epidemiologic analyses as well as institutional long-term CAR-T recipient cohort studies provide important additional information suggesting the risk of T-cell lymphomas after CAR-T therapies is extremely low. This review will provide a summary of information available to date, as well as review relevant prior research suggesting a low susceptibility of mature T cells to insertional oncogenesis and documenting the almost complete lack of T-cell transformation after natural HIV infection. Alternative factors that may predispose patients treated with CAR-Ts to secondary hematologic malignancies, including immune dysfunction and clonal hematopoiesis, are discussed, and likely play a greater role than insertional mutagenesis in secondary malignancies after CAR therapies.

Introduction

In November 2023, clinicians, scientists, and patients were shaken by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announcing that they had become aware of 22 T-cell malignancies in patients receiving chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells (CAR-Ts).1 All had a latency of <2 years from CAR-T infusion, and were seen after 5 of 6 approved CAR-T products targeting CD19 or B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA). At least 3 had some evidence for integrated clonal vector, raising a concern regarding insertional genotoxicity. The FDA estimated that a minimum of 27 000 doses of CAR-Ts had been infused in the United States, thus concluded that the risk was likely very low but were concerned about underreporting. The FDA finalized a response to these events in March 2024,2 and required black box warnings to be added to each CAR-T product’s labeling.

At the time of these events, virtually no public data existed about these cases, but over the past 9 months, more has become available on individual cases, along with epidemiologic analyses and several detailed long-term follow-up studies of CAR-T recipient cohorts. Additional insights can be gained from decades of research on the susceptibility of mature T cells to insertional mutagenesis; patterns of wild-type HIV as well as retroviral (RV) and lentiviral (LV) vector insertions into the T-cell genome; clonality studies after CAR-T infusions; and associations between T-cell malignancies and HIV infections, other immune dysregulations, B-cell malignancies, and clonal hematopoiesis (CH). Synthesizing this information will inform risk assessment and provide insights into pathophysiology, particularly regarding the potential for insertional mutagenesis related to the viral vectors used to introduce CARs into T cells. A better understanding will also guide the workup of patients presenting with secondary malignancies after CAR-T therapy.

Approaches to tracking clonal dynamics and linking vector insertion to neoplasia

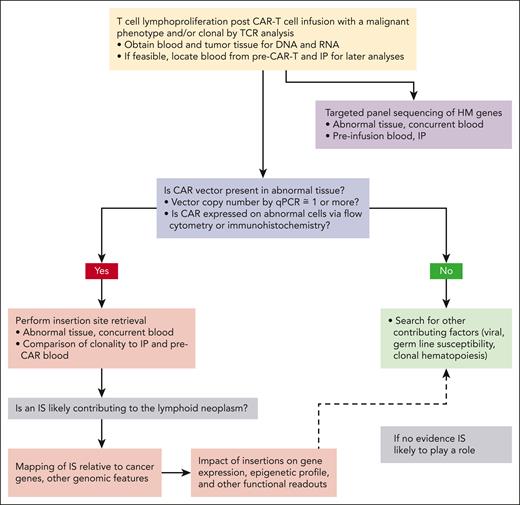

Upon discovery of potentially neoplastic T cells in a CAR-T recipient, the key question is whether CAR vector insertion(s) likely played a role in causality (Figure 1). Flow cytometric or immunohistochemical analyses for expression of the CAR on tumor cells can be performed with an anti-CAR antibody, but a negative result is insufficient to completely rule out derivation of the tumor from CAR-Ts because of potential epigenetic down regulation of CAR expression or rearrangement of vector sequences in the integrated provirus. Therefore, the key assay is quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for vector sequences to measure CAR vector copy number (VCN) in tumor DNA, ideally sorting cells in advance for a phenotypic tumor marker not expressed by normal CAR-Ts. Such assays have been described for axicabtagene ciloleuce (axi-cel), tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel), and ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel),3-5 however, a set of standards must be produced and included for quantitation. Reaching out to the vector manufacturer, the FDA, and/or centers with demonstrated published experience in analyzing tumors for vector VCN3 for advice and assistance is strongly recommended.3 A VCN close to or >1 indicates ≥1 vector integration/cell, whereas a much lower VCN likely represents detection of small numbers of persistent CAR-Ts lodged in the tumor. Use of overlapping sets of primers spanning the entire vector is desirable to definitively rule out integrated provirus, given the occurrence of rearrangements of deletions in vector sequences that may be missed using a single set of primers.3,6 The VCN will also help define the number of insertion sites (ISs) that need to be identified to fully assess the potential impact of each IS to transformation.

Schematic of suggested workup and analysis of T-cell lymphoproliferation or possible tumor in a recipient of CAR-Ts. qPCR, quantitative PCR.

Schematic of suggested workup and analysis of T-cell lymphoproliferation or possible tumor in a recipient of CAR-Ts. qPCR, quantitative PCR.

T-cell clonality is standardly assessed via quantitative T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangement assays using consensus protocols applied by many pathology departments to workup any potential T-cell neoplasm. These generally available assays can be performed as a rapid first step to confirm clonality if sufficient tumor material is available, but if material is limiting, VCN and IS analyses are more important.7 TCR clonality does not imply derivation from CAR-Ts in the absence of documentation of integrated clonal CAR vector. It is possible that an expanded TCR clone, neoplastic or not, could have been present during manufacture of the CAR-T infusion product (IP), thus TCR, VCN, IS, and mutation studies on blood before infusion and on the IP should be performed if feasible and can be helpful in sorting out clonal relationships. Single-cell genomics analyses of TCR and CAR expression can also be revealing for assessing nonhomogeneous tumor samples but would not be an initial step.

For tumor cells documented to contain clonal CAR vector at a VCN close to or >1, the vector-genome IS needs to be defined and mapped to the genome. Methodologies to retrieve RV or LV ISs have increased in sensitivity and quantitative accuracy over the past 3 decades. Current approaches rely on linear amplification from known integrated proviral sequences across the IS into the cellular genome, followed by restriction enzyme cutting or physical shearing, linker ligation, and PCR amplification of these vector/genome fragments.8 Next-generation sequencing results in semiquantitative capture of the IS, with up to tens to hundreds of thousands of reads per sample retrieved and then available to be mapped on the human genome via application of bioinformatic algorithms.9 A clonal tumor would be expected to contain 1 or several distinct ISs with similar read counts, based on a single or multiple insertions of the CAR provirus per tumor cell, vs a more polyclonal pattern in the IP or in the blood after CAR-T infusion and in vivo expansion. The number of ISs retrieved should match or approach the VCN. Individual clones of interest can be tracked across samples via design of specific PCR primers flanking the IS. IS retrieval and mapping of both LV and RV vectors is commercially available in the United States and worldwide, or as noted above, collaboration with an interested and expert academic laboratory may be desirable.

Assigning likelihood of causality to an IS found in clonally expanded or overtly malignant cells is not always straightforward. Vector insertions can contribute to transformation via at least 4 mechanisms10: (1) enhancer activation of proto-oncogene expression within up to 300 kb from the IS; (2) promoter insertion resulting in direct stimulation of expression from an immediately adjacent proto-oncogene; (3) insertional inactivation of a tumor suppressor gene; and (4) disruption of splicing or creation of 3′ messenger RNA (mRNA) truncations affecting stability, resulting in aberrant expression. RV insertions cluster in regions near transcription start sites, and LV insertions are favored throughout the entire gene,11,12 with both vector classes favoring sites in or near genes active in transduced cells. The impact of each IS on the entire genomic region, particularly those within 300 kb of cancer genes defined by databases such as the Catalog of Somatic Mutations in Cancer, can also be investigated via additional studies such as RNA sequencing, likely requiring collaborations with established experts.10 The finding of an IS within or near the same gene in tumor occurring in >1 patient is particularly strong evidence for the proviral insertion playing a role in causality.

IS analyses have been invaluable for providing new insights into the clonal dynamics of normal hematopoiesis after hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) RV or LV gene addition therapies,13 uncovering expanding HSPC clones,14 and investigating the role of insertional genotoxicity in clonal expansions and hematologic malignancies after HSPC gene therapies.14-16 For instance, RV insertional activation of LMO2 or of MECOM was implicated in frequent T-lymphoid and myeloid leukemias respectively arising in patients enrolled in pioneering RV HSPC gene therapy trials. These events resulted in a shift from RV to LV vector use for subsequent HSPC gene therapies, based on a predicted lower risk of genotoxicity because of LV insertion patterns and removal of strong constitutive promoters/enhancers from most LV vectors. However, recently LV insertional genotoxicities have also been implicated in myeloid neoplasms arising in patients with cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy treated with HSPC gene therapies, likely because of inclusion of a very strong RV promoter/enhancer within the LV vector and confirming that any integrating vector can be oncogenic.17 Much less data had existed for ISs in transduced mature T cells, but recent studies show similar propensities as in HSPCs, with RV ISs favoring transcription start sites, and LV ISs favoring intergenic regions.18,19

It is important to stress that detection of IS in leukemic cells after gene therapy does not always imply a contribution to transformation. For instance, acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) cells in a patient with sickle cell disease treated with HSPC LV gene therapy contained a clonal IS near VMA4, however, this gene has never been implicated in cancer, and no change in expression of this or any other gene near the IS could be detected.20 Patients with sickle cell disease appear to have a higher risk for myeloid leukemias, potentially resulting from chronic hypoxic marrow stress, particularly after transplantation if cells with TP53 mutations are detectable before transplant.21,22 In both autologous HSPC and T-cell gene therapies, ex vivo expansion during transduction and in vivo expansion after infusion into a lymphodepleted recipient may favor cells with preexisting driver mutations.

It is important to perform targeted sequencing panels looking for mutations in genes previously implicated in hematologic malignancies, studying both the tumor itself and, whenever possible, the IP and pre–CAR-T blood. Such panels are routinely available from commercial or academic laboratories for workup of clinical tumors or to detect CH. Cells with lymphoid malignancy or CH driver gene mutations may already be present and may expand during manufacturing or after infusion. CAR transduction of T cells already containing such mutations may result in vector sequences being present in tumor cells without contributing to neoplastic transformation. It can be quite challenging to attribute causality, as we demonstrate below for some of the T-cell tumors reported.

Clonal analyses and outcomes after natural infections with HIV

Pioneering research identifying new oncogenes via retrieval of DNA flanking clonal ISs in tumors relied on prenatal infection of mice already predisposed to lymphoma with replication-competent murine retroviruses.23 This model exposes fetal T-cell progenitors in the thymus to multiple rounds of viral infection, thus are not informative regarding insertional transformation of mature T cells. Patients with HIV infection host many billions of CD4+ T cells with proviral insertions, therefore might be a natural model for elucidating risks of insertional genotoxicity from LV vectors with HIV backbones used for T-cell gene therapies. However, most HIV-infected T cells are killed after infection, and life expectancies for patients who were HIV+ before highly effective antiretroviral therapies (HAART) limited the time these patients were at risk for secondary tumor development.

Epidemiologic studies before HAART reported only that 1% to 3% of lymphomas in patient who are HIV+ were T cell in origin, with the vast majority being B cell. The few T-cell lymphomas reported were CD4+ peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs) or adult T-cell leukemias in patients from the Caribbean likely coinfected with human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1.24,25 Only a single case of clonally integrated HIV in a T-cell lymphoma has been reported, leading to activation of the nearby FES tyrosine kinase gene.26,27FES expression has been implicated in rare non-HIV+ T-cell lymphomas.28 Several other T-cell lymphomas arising in patients with HIV infection expressed Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) genes, suggesting a link with immunosuppression rather than direct HIV causality.29,30

On HAART, a small but persistent pool of latently HIV-infected CD4+ T cells persist indefinitely,31 meaning that individuals can harbor hundreds of thousands to millions of cells with integrated HIV for decades, without evidence for an increased risk of T-cell lymphoma. However, quiescent T cells may be less susceptible to transformation, given that cell proliferation may be needed to result in mutational selection events. Thus, the type of chronic immune stimulation CAR-Ts are exposed to from residual tumor or normal cells expressing the CAR target may not be fully reflected by latent natural HIV infection. A landmark study cataloged proviral ISs in CD4+ cells from 5 individuals who were HIV+ before and after years on HAART. Clonal diversity was very high early in infection/before HAART and fell significantly over time on treatment. Notably, clonal expansions were frequent, with a single clone comprising 58% of infected cells in 1 patient.32 The IS was within the HORMAD2 gene, encoding a protein involved in meiosis, never associated with lymphoma but ectopically expressed in up to 10% of lung cancers. Several additional genes were markedly overrepresented in clonal expansions found across multiple patients, most notably BACH2 and MKL2. Of note, the BACH2 transcription factor inhibits development of effector memory and increases naïve T cells. These expansions persisted for up to 11 years without neoplastic transformation. In summary, there is little evidence that natural LV infection with HIV results in insertional neoplastic transformation of CD4 T cells, despite orders of magnitudes greater “person-years” of follow-up in patients with HIV infection compared with CAR-T recipients.

Susceptibility of mature T cells to insertional neoplastic transformation

Clear evidence implicating RV vector insertions in leukemias arising in patients enrolled in early HSPC gene therapy trials led investigators to ask whether other target cells such as mature T cells were also susceptible. One study compared RV transduction of murine HSPCs vs T cells in a serial transplantation model, using T-cell–deficient recipients and including oncogenes linked to T-cell leukemogenesis within the RV to skew the system strongly toward transformation.33 All animals receiving transduced HSPCs developed T-cell tumors in contrast to none receiving transduced mature T cells. The authors concluded that even in this “worst case” scenario, mature T cells were highly resistant to transformation. Clonal immortalization of murine T cells in vitro has been observed after transduction with an RV expressing Lmo2 and activating interleukin-2 (IL-2) and/or IL-15 expression, and human T cells transduced with a vector expressing IL-15 could also be immortalized.34,35 However, these T cells were not tumorigenic in vivo, leading to the hypothesis that clonal expansion of T cells expressing a single TCR may be limited by competition for interaction with “niches” presenting peptides via a specific major histocompatibility complex, or/and via competition for stimulatory cytokines. Coinfusion of polyclonal T cells can inhibit outgrowth of transformed T-cell clones in murine models.36 CAR-Ts survive or proliferate independent of TCR engagement in vitro during manufacturing, and are delivered to patients in the setting of lymphodepletion, factors that at least theoretically could increase the risk of transformation because of the absence of these normal T-cell homeostatic controls.

T-cell lymphomas after CAR-T therapies

Cases linked to piggyBac transposons

Ten patients were enrolled in a first-in-human trial using piggyBac transposons to introduce CD19 CARs into allogeneic donor T cells for treatment of relapsed lymphoma after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.37 Two patients developed CD4+CAR+ T-cell lymphomas at 3 and 12 months after infusion, respectively.38 Tumor cells had high surface CAR expression compared with blood CAR-Ts, and VCNs were very high (24 and 4 in the 2 tumors, respectively). Despite inclusion of insulators in the piggyBac construct, there was increased transcription of genes as far away as 1000 kb from the IS in the tumors.38 None of the ISs were within Catalog of Somatic Mutations in Cancer database cancer genes, however, in the first tumor, overexpression of FYN was observed, a proto-oncogene mutated in 4% of spontaneous PTCL,39 and only 100 kb away from the nearest IS. Both tumors had insertions within BACH2, a recurrent IS for RV and LV in the absence of tumorigenesis, and thus likely not involved in transformation.

Clinical trials using piggyBac CAR-Ts were halted. However, firm evidence implicating insertional mutagenesis as a primary mechanism was weak for the first tumor and lacking in the second. The investigators postulated potential roles for the high voltage electroporation used to introduce piggyBac into T cells, off-target effects of the transposase, high levels of DNA breaks, and/or prolonged ex vivo culture before infusion. Regulatory agencies attributed the events to unique aspects of the piggyBac system, and both clinical trial and commercial infusions of CAR-Ts with RV and LV were allowed to proceed.

T-cell lymphomas with proviral insertions

The first case of CAR-T–derived T-cell lymphoma with documented proviral vector insertion was reported at the American Society of Hematology meeting in 2023,40 just after the FDA notice of concern (Table 1). A 51-year-old man with multiple myeloma received BCMA CAR-T (cilta-cel) produced with an LV. After achieving complete remission, CD3+CD4−CD8−EBER− T-cell lymphoma was discovered at 5 months. Tumor cells were >90% positive for the CAR and clonal by TCR analysis. The same clone could be found in the IP at very low level but increased in the blood 300-fold by the time of lymphoma diagnosis. The CAR LV was inserted within the 3′ untranslated region of the PBX2 gene, which encodes a transcription factor of poorly understood function. No data on the impact of the IS on PBX2 expression were included in the abstract. The tumor also contained somatic mutations in cancer-related genes, including TET2, PTPRB, and NFKB. In addition, the patient had an activating JAK3 germ line variant previously linked to anaplastic T-cell lymphoma.41 The authors concluded that germ line predisposition combined with preexisting somatic mutations more likely contributed to the lymphomagenesis, rather than insertional genotoxicity.

T-cell lymphomas in patients receiving CAR-Ts

| Case reference . | Vector . | CAR target . | Costim∗ . | Age, y . | Latency,∗ mo . | Tumor phenotype . | Vector insertion(s) . | Additional mutation(s) in tumor . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micklethwaite et al38 | piggyBac | CD19 | 4-1BB | 66 | 3 | CD3+CD4+ | 24 total, 1 ↑FYN | PIGA, multiple CNVs |

| Micklethwaite et al38 | piggyBac | CD19 | 4-1BB | 30 | 12 | CD3−CD8+ | 4 total, 1 ↑ lncRNA | Multiple CNVs |

| Harrison et al40 | LV | BCMA | 4-1BB | 51 | 5 | CD3+CD4−CD8− | PBX2 3′ UTR | TET2, PTPRB, NFKB, germ line JAK3 |

| Ozdemirli et al5 | LV | BCMA | 4-1BB | 71 | 4 | CD3+CD4+ | SSU72 intron | KRAS, MYB, CBLC, ATM |

| Ghilardi et al49 | RV | CD19 | CD28 | 64 | 3 | CD3+CD4+ | None | JAK3 VUS |

| Hamilton et al3 | RV | CD19 | CD28 | 59 | 2 | CD3+CD4+EBV+ | None | FYN, TET2, DNMT3A |

| Case reference . | Vector . | CAR target . | Costim∗ . | Age, y . | Latency,∗ mo . | Tumor phenotype . | Vector insertion(s) . | Additional mutation(s) in tumor . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micklethwaite et al38 | piggyBac | CD19 | 4-1BB | 66 | 3 | CD3+CD4+ | 24 total, 1 ↑FYN | PIGA, multiple CNVs |

| Micklethwaite et al38 | piggyBac | CD19 | 4-1BB | 30 | 12 | CD3−CD8+ | 4 total, 1 ↑ lncRNA | Multiple CNVs |

| Harrison et al40 | LV | BCMA | 4-1BB | 51 | 5 | CD3+CD4−CD8− | PBX2 3′ UTR | TET2, PTPRB, NFKB, germ line JAK3 |

| Ozdemirli et al5 | LV | BCMA | 4-1BB | 71 | 4 | CD3+CD4+ | SSU72 intron | KRAS, MYB, CBLC, ATM |

| Ghilardi et al49 | RV | CD19 | CD28 | 64 | 3 | CD3+CD4+ | None | JAK3 VUS |

| Hamilton et al3 | RV | CD19 | CD28 | 59 | 2 | CD3+CD4+EBV+ | None | FYN, TET2, DNMT3A |

CNV, copy number variation; UTR, untranslated region.

Costim, costimulatory domain used in the CAR construct; Latency, time from CAR-T infusion.

A recent publication concerned a 71-year-old woman with a history of large granular lymphocytosis (LGL) and multiple myeloma (Table 1).5 She received BCMA CAR-T (cilta-cel); 4 months later she was diagnosed with diffuse intestinal CD3+CD4+EBER− lymphoma, with a clonal TCR distinct from her prior LGL. The same clonal TCR constituted 10% of circulating lymphocytes. High levels of CAR-encoded mRNAs were present in the tumor. The IS was in an intron of SSU72, encoding a dephosphatase involved in RNA synthesis and not previously linked to cancer but found essential for maintaining homeostatic balance between CD4 effector and regulatory T cells.42 However, no mutations in SSU72 transcripts were detected, and the ratio of mRNA expression from the provirally interrupted vs normal SSU72 alleles was not skewed, suggesting no impact on gene expression. The lymphoma also carried multiple somatic mutations, including in oncogenes KRAS, MYB, CBLC, and ATM. In summary, there was no convincing evidence that the LV insertion was a primary driver of T-cell lymphomagenesis. The patient’s history of autoimmunity/LGL were potential predisposing factors for her second T-cell neoplasm.

T-cell clonal expansions linked to proviral insertions

Before the above 2 reports of CAR+ T-cell lymphomas, several CAR-T clonal expansions had been reported, suggesting that CAR vector insertions could affect T-cell proliferation and survival. A patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) was investigated in depth after CD19 CAR-T because of a surprising pattern of response (Table 1). Initial limited primary CAR-T expansion occurred without CLL response, followed by a much larger second expansion at 1 month, coinciding with complete remission of CLL, now maintained for >5 years.43 The IP and initial expansion were polyclonal, but a surprising conversion to TCR monoclonality occurred during the second massive expansion, calculated to represent 29 population doublings, before contraction occurred after CLL remission.

The IS was in intron 9 of the TET2 gene, with premature termination and abnormal splicing resulting in loss of demethylase activity. TET2 insufficiency is a common driver of CH, as well as being associated with lymphomas and leukemias.44 Notably, the CAR-T clone had an acquired loss-of-function mutation in the other TET2 allele, resulting in complete loss of TET2 function. This somatic TET2 mutation was present in T cells from before infusion. The CAR-T clone had a central memory phenotype, in contrast to the more typical effector memory phenotype seen in other patients receiving CAR-Ts. The clone remained nonmalignant and retained homeostatic and antigen-dependent controls, evidenced by contraction coincident with recovery of non-CAR+ T cells and sustained depletion of CD19+ target cells.

A second patient demonstrated a similar pattern of nonmalignant clonal expansion.45 A 28-year-old woman received CD22 CAR-Ts for refractory pre–B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. After primary in vivo expansion and disease response, the CAR-Ts contracted as expected but expanded markedly again a month later while the patient remained in complete remission. The cells were 90% clonal via TCR sequencing, contained provirus on VCN analysis, and had a proviral insertion in the second intron of the CBL gene. The other CBL allele was normal. The clone then contracted and became undetectable by day 180, when the patient relapsed with CD22− acute lymphoblastic leukemia. CBL is a tyrosine kinase and is known to be involved in TCR signaling. Complete loss in murine models reduces the threshold for T-cell activation and need for costimulation, but haploinsufficiency of CBL had no effect on T cells in prior studies.46 This report did not examine the impact of the insertion on CBL expression or splicing, and thus the mechanism of a link between the insertion and the clonal expansion is unclear.

Comprehensive surveys of CAR-T clonality

Insights into the clonal behavior of CAR-Ts in the absence of suspected clonal expansions or tumors have been gained through long-term IS tracking studies. CAR-Ts were first administered to patients with HIV infection, using CARs consisting of a gp210-binding CD4 extracellular domain fused to the CD3ζ signaling domain, before the discovery that costimulatory domains were necessary for in vivo CAR-T persistence and function. More than 7000 RV insertions in 11 patients were tracked for up to 11 years.47 CAR-Ts were detectable throughout at very low levels, with stable clonal patterns and no detected expansions. Insertions near oncogenes were not enriched over time.

After the reports of remarkable clonal expansions summarized above, comprehensive studies were performed by 2 groups analyzing 49 patients receiving LV-transduced CD19 CAR-Ts.18,48 Both studies found persistent polyclonality, however a drop in overall clonal population size occurred between the IP and initial in vivo samples, with further loss of population size over time in subsets of patients studied longitudinally. TCR clonality did not predict IS clonality, with TCR clonality linked to pretransduction-expanded T-cell clones. No additional clonal expansions defined by IS were noted after infusion. Thus, clonal expansions, as defined by IS, appear to be relatively rare events, although patient numbers studied are relatively low.

Even in the absence of overt clonal expansions, there is additional evidence that IS may affect in vivo persistence. TET2 ISs were overrepresented across patients.18 A comparison of IS patterns in CLL CAR-T responders vs nonresponders found enhancement of cells with ISs affecting signal transduction or chromatin remodeling genes. A multivariate model based on the IS profile in the IP was constructed to predict tumor response, with good predictive value in a validation cohort. An independent study compared integration patterns in 28 patients receiving CD22 CAR-Ts produced with either RV or LV, showing, unsurprisingly, a larger impact of RV on the overall transcriptome, and some correlation of clinical outcomes with enrichment of specific IS patterns in the IP.48 It is inherently difficult to conclude whether specific IS patterns are the “chicken” or the “egg,” given the propensity for IS cluster in active genes, and thus IS overrepresentation in persistent CAR-Ts may simply reflect favored integration regions in cells with more self-renewal capabilities at the time of transduction, rather than the insertions themselves affecting the persistence of these T cells in vivo.

T-cell lymphoma cases without evidence for proviral insertions

As part of a cohort analysis performed at the University of Pennsylvania, a detailed analysis of a T-cell lymphoma arising in a 64-year-old male with a history of autoimmunity and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) was presented.49 He had been extensively treated with chemotherapy and pembrolizumab before RV CD19 CAR-T (axi-cel; Table 1). Three months later he was serendipitously discovered to have PTCL in a thoracic lymph node removed during workup for lung cancer. The lymphoma cells were CD3+CD4dimCD8+EBER−, and the CAR VCN was only 0.005%, attributed to residual blood CAR-Ts, however, only a single primer set was used, and a grossly rearranged vector might not have been detected. Targeted oncogene sequencing of the tumor revealed a JAK3 variant of uncertain significance at a variant allele frequency (VAF) of 11%. The lymphoma was TCRγ clonal, and the clone could be detected in blood before CAR-T infusion at a level of <0.01%.

A second T-cell lymphoma without evidence for proviral insertion was reported as part of a Stanford cohort.3 A 59-year-old female with EBV+ DLBCL and severe psoriasis requiring multiple immunosuppressive therapies received CD19 CAR-T (axi-cel). Bone marrow biopsy performed on day 58 for persistent cytopenias revealed infiltration of CD3+CD4+CD8−EBER+ T-cell lymphoma. The tumor was TCRβ clonal and could be detected in the blood at a low level before CAR-T therapy. Notably, the plasma load of EBV rose markedly after lymphodepletion/CAR-T infusion. A comprehensive search for integrated provirus via 112 overlapping probes covering the entire vector was negative. Tumor sequencing identified a clonal activating FYN mutation, lacking in myeloid cells and in the DLBCL. In addition, 2 TET2 and 1 DNMT3A mutations were detected in the T-cell lymphoma and the DLBCL, as well as in the blood at lower but still significant VAF, suggesting both B- and T-cell tumors originated from HSPCs with these CH mutations.

Cohort and epidemiologic studies of secondary malignancies after CAR-T therapies

In response to the initial 2023 FDA notice, an analysis of 12 394 entries in the FDA’s Adverse Events Reporting System for the 6 FDA-approved CAR-T products was performed.50 After identifying >2000 adverse events classified as “neoplasms” and excluding those related to the primary cancer/preexisting cancer, 536 events were analyzed. The majority were in patients receiving axi-cel and tisa-cel, as expected based on dates of approval and relative usage. At least 62% of the neoplasms were myeloid. Seventeen T-cell lymphomas were reported (3.2%) and included 12 anaplastic large cell, 3 peripheral, 1 angioimmunoblastic, and 1 enteropathy-associated lymphomas, and 2 LGL. These tumors were associated with both RV or LV CAR vectors containing either CD28 or 4-1BB domains and targeting CD19 or BCMA. This study relied solely on information in the FDA database, with no further investigation of the cases. Odds ratios were calculated via comparison with secondary malignancies reported in patients receiving non–CAR-T therapies for the same underlying tumor. Of 6 products, 5 had disproportionately higher reporting odds for myeloid tumors, an important finding independent of T-cell lymphoma concerns, and consistent with a recent report showing earlier onset and higher rates of myeloid neoplasms after CAR-Ts compared with autologous hematopoietic cell transplant.51 Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma had a slightly higher odds ratio after tisa-cel, the only positive signal.

Long-term follow-up of institutional cohorts were undertaken by 4 CAR-T clinical research centers or consortia, both before and in response to the 2023 FDA announcement. The University of Pennsylvania and National Cancer Institute groups initiated pioneering clinical trials of CAR-T in 2009, and their series of 38 and 43 patients, respectively, included patients followed-up for 3 to 9 years.52,53 Neither reported T-cell lymphomas but documented multiple secondary myeloid tumors, as expected for patients heavily pretreated with chemotherapy, including autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. CAR-Ts could be detected at very low levels in many patients, even years after infusion. Stanford University investigators reported on 724 patients receiving a variety of cell therapies, the majority CAR-Ts, with a relatively short median follow-up of 15 months, documenting 24 secondary tumors, including 13 myeloid, and 1 T-cell malignancy (the case detailed above lacking vector).3 A retrospective multicenter analysis of 420 pediatric/young adult patients not surprisingly reported a lower rate of secondary malignancies than seen in the adult cohorts, and no T-cell lymphomas.54 Baylor College of Medicine recorded up to 30 years follow-up of 340 adult and pediatric patients receiving T cells transduced with RV carrying marker genes, suicide genes, CARs against various targets, or immune effector genes. With 1027 total patient-years of follow-up, 13 patients (3.8%) developed 16 secondary neoplasms, including 3 myeloid, and 1 T-cell lymphoma reported negative for vector occurring 36 months after infusion of HER2-CAR for glioblastoma.55,56 In summary, these cohorts detected a total of 3 T-cell lymphomas, none containing vector, in >1500 patients with lengths of follow-up in a substantial majority over 2 years, the longest latency in the FDA 2023 notice. A very recent meta-analysis of published CAR-T data, including 5517 patients receiving CAR-Ts for lymphoma or myeloma and incorporating most of the studies summarized above, came to similar conclusions, with 6% of patients developing second primary malignancies at a mean follow-up of 21 months, and T-cell malignancies constituting only 1.5% of these tumors.57 Interestingly, they performed a subgroup analysis of the randomized controlled CAR-T trials incorporating a standard-of-care arm, and found no higher risk of secondary tumors for CAR-Ts vs standard-of-care.

Additional factors potentially increasing the risk of T-cell malignancies in CAR-T recipients

The vast majority of patients receiving CAR-Ts to date, particularly those surviving several years or longer, have underlying B-cell malignancies. A recent registry analysis found a fivefold higher risk of T-cell lymphomas in patients with prior B-cell lymphomas.58 In addition, several other plausible factors may predispose to T-cell lymphoma in CAR-T recipients, including autoimmune disorders requiring immunosuppressive therapy, immunosuppression related to treatment of B-cell malignancies, viral reactivation, and/or CH accelerated by prior cytotoxic chemotherapy, all known predisposing factors.

Three patients with T-cell lymphoma also had CH predating CAR-T infusions, with the same CH mutations detected in the T-cell tumors. It is well established that mutations in genes including DNMT3A, TET2, TP53, and JAKs can result in clonal expansion in the setting of proliferative stress after autologous stem cell transplantation.59,60 Studies have also shown an increase in the VAF of CH mutations after CAR-T therapy.61-63 CH has been increasingly implicated as an underlying factor in T-cell lymphomas, particularly PTCL, with the same mutations found in nontransformed myeloid blood cells; T-cell lymphoma cells; and, in some cases, preceding or subsequent myeloid and B-cell tumors.64,65 Although ex vivo culture, in vivo expansion in the setting of lymphodepletion, and cytokine-mediated inflammation could have accelerated any of these underlying processes, insertional mutagenesis seems unlikely to be the sole causal factor, even in tumors with proviral integrations.

Conclusions and future directions

Although review of current evidence does not suggest that clinical decisions should be altered for patients eligible for CAR-Ts based on concerns regarding T-cell lymphomas, there is a finite risk of insertional transformation when billions of T cells have their genome semirandomly interrupted by an integrating vector. Mature T cells are much less susceptible to insertional genotoxicity than HSPCs, and insights gained from analyses of natural HIV infections suggest the risk is very low, particularly because CAR vectors generally do not contain strong internal viral promoter/enhancers, whether in the context of RV or LV backbones. Sustained proliferation of CAR-Ts during manufacturing and in vivo after infusions likely favor the expansion of cells with preexisting or new somatic mutations, including insertions changing expression of genes involved in cancer. But underlying patient factors such as a genetic predisposition to malignancy, autoimmunity, other types of immune dysfunction, immunodeficiency related to prior treatments, and/or CH accelerated by aging and prior cytotoxic therapies are likely more relevant risk factors than clonal outgrowth solely due to proviral insertions. Most of these additional risk factors are not modifiable, and clearly predispose CAR-T recipients to secondary myeloid neoplasms much more frequently than T-cell lymphomas.

Several approaches have been developed that would be predicted to decrease the already very low risk of T-cell malignancies after CAR-T therapy. “On-off” switches or suicide genes could be included within CAR vectors, allowing “on-demand” depletion of CAR-T–derived clonal expansions or even overt tumors.66 Targeted genomic introduction of CAR constructs via CRISPR/Cas or other nucleases could theoretically greatly reduce insertional genotoxicity, however, such approaches are less well studied long term in model animals or patients, and persistent chromosomal translocations after infusion of edited CAR-Ts have been detected.67 In vivo creation of CAR-Ts via administration of T-cell targeted viral or nonviral vectors avoids risks associated with in vitro manufacturing and in vivo lymphodepletion68 but, depending on the vector system used, could still result in insertional genotoxicity. Finally, “hit and run” strategies have been explored using mismatched third-party CAR-Ts that are rapidly rejected, natural killer CAR cells with more limited self-renewal potential, or production of CAR-Ts using nonintegrating vectors that will be diluted out with cell divisions. However, these approaches preclude ongoing tumor surveillance by CAR-expressing cells, therefore losing the main at least theoretical advantage of cellular therapies over drugs such as T-cell–activating bispecific antibodies.

It is also important going forward to standardize and incentivize long-term follow-up and safety monitoring. It is very challenging to prospectively organize, pay for, collect, store, and control access to samples from patients that then may become necessary for complete workup of tumors (Figure 1), including pre-CAR blood samples, IPs, and the tumors themselves. The workup of such events, as detailed in this review, can be complicated, expensive, and require laboratory and analytic approaches that are not widely available, particularly to clinicians who may have administered commercial CAR-T products. CAR-T product approvals stipulate 15 years of monitoring, and patients are asked to sign an informed consent follow-up but even academic centers struggle to maintain contact with many patients for anywhere near this length of time. There are few incentives for patients to continue to travel to cell therapy treatment centers (the institutions responsible for FDA and registry reporting) once they have recovered from the acute effects of CAR-T therapies. As indications expand to solid tumors and nonmalignant disorders, follow-up may become even more difficult, given the lack of familiarity of primary oncologists or other subspecialists with the long-term concerns and reporting pathways for cell and gene therapies.

The FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database has information on only ∼8000 patients, despite estimates of >35 000 CAR-T infusions.69 Regulatory agencies, registries, and funding agencies need to work together to design a practical follow-up approach, incentivizing patients, industry, and physicians to procure and store samples and report outcomes. Any clinicians or investigators encountering patients with second malignancies after CAR-T therapies are encouraged to immediately report them to the FDA (http://www.fda.gov/medwatch) or appropriate non-US regulatory agencies, both to receive advice regarding appropriate next steps in workup of the tumor, and to inform ongoing and future risk assessments for CAR-T therapies.

Acknowledgments

C.E.D. is supported by the intramural research program of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health. J.H. is supported by grant 82330005 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Authorship

Contribution: J.H. and C.E.D. contributed to literature review and writing and revision of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.E.D. receives research support from Novartis, Be Bio, and Disc Medicine. J.H. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Cynthia E. Dunbar, Translational Stem Cell Biology Branch, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Room 5E-3332, Building 10-CRC, 9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD 20892; email: dunbarc@nhlbi.nih.gov.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal