Key Points

CM-TMA has a classical pathway stimulus driven by polyreactive IgM, addressing why 40% of CM-TMA lack complement-specific variants.

Complement biosensors can be used to monitor classical and alternative pathway activity and aid in the diagnosis of CM-TMA.

Visual Abstract

Complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy (CM-TMA) or hemolytic uremic syndrome, previously identified as atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome, is a TMA characterized by germ line variants or acquired antibodies to complement proteins and regulators. Building upon our prior experience with the modified Ham (mHam) assay for ex vivo diagnosis of complementopathies, we have developed an array of cell-based complement “biosensors” by selective removal of complement regulatory proteins (CD55 and CD59, CD46, or a combination thereof) in an autonomously bioluminescent HEK293 cell line. These biosensors can be used as a sensitive method for diagnosing CM-TMA and monitoring therapeutic complement blockade. Using specific complement pathway inhibitors, this model identifies immunoglobulin M (IgM)–driven classical pathway stimulus during both acute disease and in many patients during clinical remission. This provides a potential explanation for ∼50% of patients with CM-TMA who lack an alternative pathway “driving” variant and suggests at least a subset of CM-TMA is characterized by a breakdown of IgM immunologic tolerance.

Introduction

Complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy (CM-TMA) is a subset of TMA characterized by complement dysregulation. CM-TMA remains a clinical diagnosis based on the exclusion of other TMA syndromes; there is no diagnostic assay. Prompt diagnosis of CM-TMA is critical because complement inhibition with C5 inhibitors is highly effective therapy.1

CM-TMA is thought to be a disorder of the alternative pathway (AP) of complement because 50% to 60% of patients harbor a germ line variant or acquired autoantibody to a protein central to this pathway (eg, C3, factor H [FH], FI, membrane cofactor protein [MCP]/CD46, and CFB).2,3 Mechanistic studies show these pathogenic variants play a direct role in cell-surface expression, gain of function/resistance to regulation, cofactor activity, or decay accelerating activity.4-6 However, these variants are neither necessary nor sufficient; 40% to 50% of patients do not carry any variant or autoantibody, and disease penetrance is only 20% to 50% in those with a known pathogenic variant.7,8 Thus, there is an unmet need for assays and/or biomarkers, not only for diagnosis but also to mechanistically explain the disease in patients without variants and the low penetrance in those with known familial pathogenic variants.

Two principal techniques for in vitro diagnosis have been proposed, including the modified Ham (mHam) assay9,10 and human microvascular endothelial cell (HMEC-1) staining for C5b-9,11-15 but neither is widely adopted. Both assays rely upon testing patient serum for abnormal cell-deposited complement activity. In the case of mHam, TF-1 erythroblasts deficient in glycosylphosphatidylinositol–linked complement regulators (decay accelerating factor [DAF]/CD55 and CD59) are used in an absorbance-based cell viability assay to assess for increased complement activity leading to cell death.9 In most versions of the HMEC-1 C5b-9 assay, wild-type (WT) HMEC-1 endothelial cells are stimulated with adenosine diphosphate, incubated with patient serum, and then assessed by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy for increased C5b-9 deposition.12

Our experience with the mHam assay on TF-1 cells and endothelial cells suggested that an additional stimulus beyond the AP was required for complement activation. First, complement-mediated cell killing was typically greater in calcium and magnesium–containing buffer permissive of all pathways (classical, lectin, and alternative) than in an AP-specific buffer (magnesium ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid [MgEGTA]).9,10 Second, patients with known pathogenic variants in membrane bound (vs soluble) complement regulators (eg, CD46) were still positive when testing their serum in either the mHam or HMEC-1 C5b-9 assays.13,16,17 Finally, both assays, as well as soluble C5b-9, remain positive or elevated in a sizable proportion of patients without an identifiable AP variant, even in hematologic remission.11,13,18 The initiation of the AP is the hydrolysis of the thioester of C3, which occurs at a slow, fixed rate according to first-order kinetics.19,20 Although enhanced tick over through contact activation or heme-induced activation has been proposed as a contributing mechanism, this would not explain ongoing complement activation in a patient with CM-TMA in hematologic remission.19,21-23 Taken together, these data suggest an additional mechanism of complement activation contributes to disease pathogenesis.

To address these observations, we used an autonomously bioluminescent HEK293 cell line that allows for real-time measurement of cellular metabolic health resulting from complement activation and obviates the need for washes or reagent addition.24 Compared with the TF-1 cell line used in the mHam, HEK293 cells lack complement receptor 1 (CR1), which strongly regulates both classical pathway (CP) and AP activity25 on cells of hematopoietic origin and renal podocytes.26 Here, we use these biosensors to probe the pathogenesis of CM-TMA and show the presence of abnormal CP activity driven by immunoglobulin M (IgM).

Methods

Patient cohort and definitions

We used 41 biobanked sera specimens from the Johns Hopkins Complement Associated Disease Registry with a diagnosis of CM-TMA or thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) (Table 1). TTP was diagnosed by ADAMTS13 activity <10%, and the diagnosis of CM-TMA was determined by a consulting hematologist. Samples were defined as acute if they were collected within 14 days of initial manifestations; had not yet received donor plasma, C5 inhibitory therapy, or caplacizumab; and had not yet achieved hematologic remission (defined as hemoglobin >11 g/dL or recovery to baseline, lactate dehydrogenase within normal limits, and platelet count >150 × 103/μL). Patients with renal-limited TMA were excluded. Two of 6 (33%) acute CM-TMA samples and 6 of 15 (40%) remission samples had a known pathogenic variant or variant of uncertain significance in a complement regulatory protein or factor H autoantibody (FHAA). Fourteen CM-TMA samples were included from patients on C5 inhibitors (either eculizumab or ravulizumab). Additionally, we included sera from 19 nonpregnant, healthy adults and 6 patients with acute TTP.

Cohort characteristics

| Patient identification . | Age at diagnosis, y/sex . | Sample collected/follow-up, y∗ . | Variant† . | Overall classification . | Trigger . | Therapy‡ . | Clinical outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute | |||||||

| CM01 | 27/F | 0/4 | NA | NA | Third pregnancy | Short-term eculizumab | Normal kidney function |

| CM02 | 14/F | 0/4 | CD46 c.286+2T>G splice site | Likely pathogenic | Influenza A | Supportive care only | Normal kidney function |

| CM03 | 9/M | 0/4 | +FHAA, homozygous del of CFHR1, compound heterozygous CFHR3-CFHR1 and CHFR1-CHFR4 deletion | Likely pathogenic | Influenza B | Long-term eculizumab | Normal kidney function |

| CM04 | 23/F | 0/5 | Homozygous del CHFR3-CHFR1, no FHAA | VUS | NA | Short-term eculizumab | Deceased (unrelated cause) |

| CM05 | 1/M | 0/3 | NMD | NA | Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis | Supportive care | Normal kidney function |

| CM06 | 59/F | 0/<1 | NA | NA | NA | On eculizumab | ESKD |

| Remission | |||||||

| CM07 | 46/F | 4/11 | Homozygous del of CFHR1-CHFR3 and heterozygous Factor H p.Gln950His | Likely pathogenic vs VUS | Kidney stone | Short-term eculizumab | CKD1 |

| CM08 | 22/F | 3/5 | NMD | NA | Possible infection | Short-term eculizumab | Normal kidney function |

| CM09 | 22/F | 4/9 | NMD | NA | Influenza-like illness | Short-term eculizumab | CKD3 |

| CM10 | 31/F | 1/4 | NMD | NA | Pregnancy | PLEX/Short-term eculizumab | ESKD |

| CM11 | 26/F | 1/2 | NMD | NA | Pregnancy | Short-term eculizumab | CKD1 |

| CM12 | 24/F | 1/1 | Heterozygous CD46 c.104G>A, p.Cys35Tyr | Likely pathogenic | COVID-19 | Supportive care | Normal kidney function |

| CM13 | 24/M | 2/8 | ADAMTS13 c.3677C>T, p.Thr1226Ile | VUS | Possible pneumonia | Short-term eculizumab | CKD4 |

| CM14 | 31/F | 3/11 | THBD (heterozygous c.1456G>T, p.Asp486Tyr), CFHR5 (heterozygous c.1357C>G,p.Pro453Ala) | Likely pathogenic | Pregnancy | PLEX and rituximab | Normal kidney function |

| CM15 | 55/M | 1/2 | NA | NA | EtOH pancreatitis | Short-term eculizumab | Normal kidney function |

| CM16 | 37/F | 1/8 | THBD het c.127G>A, p.Ala43Thr and het del CHFR3-CFHR1 with novel fusion protein of the first 19 SCR of CFH and SCR 5 of CFHR1 | Likely pathogenic | Possibly IBD related | Long-term ravulizumab | Normal kidney function |

| CM17 | 51/M | 1/8 | het CD46 p.Ser274Tyrfs∗, het CFH p.Arg1074Pro, het del CFHR3-CFHR1 | Likely pathogenic | Unknown | Short-term eculizumab | Normal kidney function |

| CM18 | 24/F | 1/9 | NMD | NA | Dental abscess | Supportive | Normal kidney function |

| CM19 | 22/F | 2/11 | NMD | NA | Unknown | Short-term | ESKD s/p transplant |

| CM20 | 37/F | 1/2 | NMD | NA | Pregnancy | PLEX only | CKD3 |

| CM21 | 2/M | 27/28 | Het C3 c.Arg592Trp | Likely pathogenic | Unknown | Long-term ravulizumab | ESKD s/p transplant (×3) |

| Patient identification . | Age at diagnosis, y/sex . | Sample collected/follow-up, y∗ . | Variant† . | Overall classification . | Trigger . | Therapy‡ . | Clinical outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute | |||||||

| CM01 | 27/F | 0/4 | NA | NA | Third pregnancy | Short-term eculizumab | Normal kidney function |

| CM02 | 14/F | 0/4 | CD46 c.286+2T>G splice site | Likely pathogenic | Influenza A | Supportive care only | Normal kidney function |

| CM03 | 9/M | 0/4 | +FHAA, homozygous del of CFHR1, compound heterozygous CFHR3-CFHR1 and CHFR1-CHFR4 deletion | Likely pathogenic | Influenza B | Long-term eculizumab | Normal kidney function |

| CM04 | 23/F | 0/5 | Homozygous del CHFR3-CHFR1, no FHAA | VUS | NA | Short-term eculizumab | Deceased (unrelated cause) |

| CM05 | 1/M | 0/3 | NMD | NA | Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis | Supportive care | Normal kidney function |

| CM06 | 59/F | 0/<1 | NA | NA | NA | On eculizumab | ESKD |

| Remission | |||||||

| CM07 | 46/F | 4/11 | Homozygous del of CFHR1-CHFR3 and heterozygous Factor H p.Gln950His | Likely pathogenic vs VUS | Kidney stone | Short-term eculizumab | CKD1 |

| CM08 | 22/F | 3/5 | NMD | NA | Possible infection | Short-term eculizumab | Normal kidney function |

| CM09 | 22/F | 4/9 | NMD | NA | Influenza-like illness | Short-term eculizumab | CKD3 |

| CM10 | 31/F | 1/4 | NMD | NA | Pregnancy | PLEX/Short-term eculizumab | ESKD |

| CM11 | 26/F | 1/2 | NMD | NA | Pregnancy | Short-term eculizumab | CKD1 |

| CM12 | 24/F | 1/1 | Heterozygous CD46 c.104G>A, p.Cys35Tyr | Likely pathogenic | COVID-19 | Supportive care | Normal kidney function |

| CM13 | 24/M | 2/8 | ADAMTS13 c.3677C>T, p.Thr1226Ile | VUS | Possible pneumonia | Short-term eculizumab | CKD4 |

| CM14 | 31/F | 3/11 | THBD (heterozygous c.1456G>T, p.Asp486Tyr), CFHR5 (heterozygous c.1357C>G,p.Pro453Ala) | Likely pathogenic | Pregnancy | PLEX and rituximab | Normal kidney function |

| CM15 | 55/M | 1/2 | NA | NA | EtOH pancreatitis | Short-term eculizumab | Normal kidney function |

| CM16 | 37/F | 1/8 | THBD het c.127G>A, p.Ala43Thr and het del CHFR3-CFHR1 with novel fusion protein of the first 19 SCR of CFH and SCR 5 of CFHR1 | Likely pathogenic | Possibly IBD related | Long-term ravulizumab | Normal kidney function |

| CM17 | 51/M | 1/8 | het CD46 p.Ser274Tyrfs∗, het CFH p.Arg1074Pro, het del CFHR3-CFHR1 | Likely pathogenic | Unknown | Short-term eculizumab | Normal kidney function |

| CM18 | 24/F | 1/9 | NMD | NA | Dental abscess | Supportive | Normal kidney function |

| CM19 | 22/F | 2/11 | NMD | NA | Unknown | Short-term | ESKD s/p transplant |

| CM20 | 37/F | 1/2 | NMD | NA | Pregnancy | PLEX only | CKD3 |

| CM21 | 2/M | 27/28 | Het C3 c.Arg592Trp | Likely pathogenic | Unknown | Long-term ravulizumab | ESKD s/p transplant (×3) |

ESKD s/p, end stage kidney disease status post; EtOH, ethanol; F, female; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; M, male; NA, not performed or not available; NMD, no mutation detected; PLEX, plasma exchange; VUS, variant of uncertain significance.

Sample collection indicates the time from diagnosis until sample was collected in years. Length of follow-up indicates the time from diagnosis in years until present.

In only 2 cases of CFHR1/CFHR3 deletion were FHAA specifically tested (CM03 and CM04). Given other cases are remission samples, they were not analyzed for FHAA but classified as likely pathogenic vs variant of uncertain significance based on homozygous deletion and known increased frequency in CM-TMA.

Short-term defined as a minimum of 5 doses or up to 2 years and around the time of kidney transplant in some cases.

Samples were collected and analyzed with the approval of the human research participants Institutional Review Board at Johns Hopkins University associated with the complement associated disease registry.

Biosensor creation

LiveLight HEK293 cell line (490 BioTech) was used to allow for real-time measurement of metabolic health.24 A PIGA knockout cell line (PIGAKO) devoid of all glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins, including complement regulators CD55 and CD59, was established by proaerolysin selection as previously described.10 CRISPR/Cas9 was used to establish an isolated MCP/CD46 knockout cell line (CD46KO) as well as a double knockout cell line (DKO) devoid of all 3 membrane bound complement regulators, CD55, CD59, and CD46.

Bioluminescent mHam assay

Forty-thousand cells were harvested with trypsin/EDTA and plated as triplicates in gelatin veronal buffer (GVB++; 80 μL). Next, serum (20 μL) was added after appropriate treatment (heat inactivation, dithiothreitol [DTT] treatment, immunoglobulin-degrading enzyme from Streptococcus pyogenes (IdeS) cleavage, or inhibitor addition as described in supplemental Methods, available on the Blood website). Relative luminescence was monitored by serial luminescence measurements (every 5 minutes at 37°C) in a BMG Clariostar luminometer. Results were plotted in GraphPad Prism.

Presensitization

CM-TMA or healthy control (HC) sera was heat inactivated and then incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C with PIGAKO or DKO cells. Cells were washed twice and resuspended in GVB++. These presensitized cells are then used in the bioluminescent mHam as described above, with HC mix serum (specifically selected for low activity on the DKO cell line).

Flow cytometry

Healthy control or CM-TMA serum was incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C with WT TF-1, HEK293, CD46KO, and PIGAKO cell lines in the presence of eculizumab alone, eculizumab + sutimlimab, or eculizumab + factor D inhibitor (FDi; ACH-5548). Heat-inactivated sera was used as a negative control. Cells were washed in Hanks balanced salt solution with 1% bovine serum albumin, stained for C3c or C4d, and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in the supplemental Methods. IgG and IgM flow cytometry was similarly performed after incubation of heat-inactivated healthy control or CM-TMA sera for 45 minutes at 37°C.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics and statistical analysis were performed in GraphPad Prism.

A complete description of experimental details can be found in the supplemental Materials.

Results

Biosensors detect range of normal complement activity among healthy controls

In the bioluminescent mHam, cells are incubated with sera for 2.5 hours, and a real-time tracing of autonomous bioluminescence is compared with heat-inactivated sera (Figure 1A-E). Heating serum is a well-established method for inactivating complement,27 and cell luminescence correlates with metabolic health and cell viability.24,28 Thus, by comparing the luminescent signal of untreated and heat-inactivated sera from the same patient, the effects of complement-mediated cell cytotoxicity are measured. Because maximal effect is typically observed at ∼1 hour, this time point was selected to report a “percent relative luminescence,” in which 100% relative luminescence represents no significant metabolic effect of complement, and 0% indicates total loss of the cell population. Using healthy control sera, the relative luminescence at 1 hour decreased as complement regulators were removed (Figure 1B-F): WT cells 90.3 (95% confidence interval [CI], 86.9-93.8), CD46KO cells 78.8 (95% CI, 67.9-89.7), PIGAKO cells 47.2 (95% CI 34.4-59.9), and DKO 20.9 (95% CI 7.9-33.9; Figure 1F). One healthy control was excluded, given the significant killing of WT cells, with further studies ongoing to determine the etiology (Figure 1F). A relative 1-hour luminescence of ≤12% for the PIGAKO line and ≤62% for the CD46KO line was used to establish a “positive” threshold for abnormal complement activity, corresponding to the lower 85th percentile on both cell lines.

Complement biosensors identify a range of “normal” complement activation in healthy control sera. (A) Overview of creation of biosensors with different susceptibilities to complement and description of the assay. (B-E) Healthy control (HC) or heat-inactivated sera incubated with Livelight WT HEK293 cells (B), CD46KO cells (C), PIGAKO cells (D), double CD46, and PIGA KO (DKO) cells (E). Relative luminescence measured every 5 minutes for 2.5 hours. Data plotted as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for each triplicate. (F) Summary of relative luminescence at 1 hour for healthy controls (WT, CD46KO, and PIGAKO, n = 19; and for DKO, n = 18). Asterisk identifies outlier by ROUT analysis (Q = 1%). P values were calculated using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for Dunnett multiple-comparisons test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. HI, heat inactivation; ns, not significant; RLU, relative luminescence units; ROUT, robust regression and outlier. Portions of figure were created with BioRender.com.

Complement biosensors identify a range of “normal” complement activation in healthy control sera. (A) Overview of creation of biosensors with different susceptibilities to complement and description of the assay. (B-E) Healthy control (HC) or heat-inactivated sera incubated with Livelight WT HEK293 cells (B), CD46KO cells (C), PIGAKO cells (D), double CD46, and PIGA KO (DKO) cells (E). Relative luminescence measured every 5 minutes for 2.5 hours. Data plotted as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for each triplicate. (F) Summary of relative luminescence at 1 hour for healthy controls (WT, CD46KO, and PIGAKO, n = 19; and for DKO, n = 18). Asterisk identifies outlier by ROUT analysis (Q = 1%). P values were calculated using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for Dunnett multiple-comparisons test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. HI, heat inactivation; ns, not significant; RLU, relative luminescence units; ROUT, robust regression and outlier. Portions of figure were created with BioRender.com.

Bioluminescent mHam on PIGAKO and CD46KO biosensors differentiates acute CM-TMA from TTP and healthy control sera

We next sought to characterize the activity in TMA samples, including CM-TMA (acute or remission) and acute TTP. Both acute and remission CM-TMA samples are significantly different from healthy controls or acute TTP, and all acute CM-TMAs have significant activity on both the PIGAKO and CD46KO biosensors (Figure 2A-E). In remission, 7 of 13 sample (54%) remain positive on the CD46KO and 8 of 14 (57%) on the PIGAKO (Figure 2B,E). Among patients with a complement variant or FHAA, 3 of 5 (60%) were positive on CD46KO compared with 4 of 8 (50%) without.

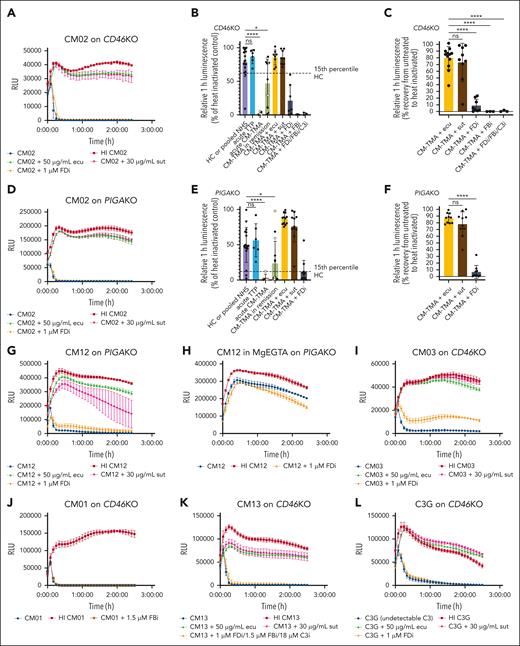

Example CM-TMA tracings and summary of relative luminescence and blocking. (A,D) CM02 sera on CD46KO cells (A) or PIGAKO cells (D) in GVB++ with or without heat inactivation (HI), eculizumab (ecu; 50 μg/mL), sutimlimab (sut; 30 μg/mL), or ACH-5548 (FDi). (B,E) Summary of relative 1-hour luminescence of healthy controls (HC), CM-TMA (acute or remission) with or without the addition of ecu, sut, ACH-4471/ACH-5548 (FDi; 1 μM), iptacopan (FBi; 1.5 μM), or “triple AP blockade” with FDi (1 μM), FBi (1.5 μM), and compstatin (18 μM) on CD46KO (B) or PIGAKO (E) (PIGAKO: HC, n = 18; acute TTP, n = 6; acute CM-TMA, n = 5; remission, n = 14; CM-TMA + ecu, n = 12; CM-TMA + sut, n = 11; CM-TMA + FDi, n = 11; CD46KO: HC, n = 18; acute TTP, n = 6; acute CM-TMA, n = 5; remission CM-TMA, n = 13; CM-TMA + ecu, n = 8; CM-TMA + sut, n = 8; CM-TMA + FDi, n = 7; CM-TMA FBi, n = 3; CM-TMA triple blockade, n = 3). Graphed as mean ± SD. Yellow fill indicates sample with pathogenic variant or variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in complement regulatory protein. Dashed line represents the 15th percentile of healthy control. (C,F) Relative 1-hour luminescence recovery after addition of inhibitor calculated at 1 hour as follows: (luminescence inhibitor-treated serum − luminescence untreated serum)/(luminescence heat-inactivated serum − luminescence untreated serum); (PIGAKO, n = 10 for each condition; CD46KO: CM-TMA + ecu, n = 12; CM-TMA + sut, n = 9; CM-TMA + FDi, n = 8; CM-TMA + FBi, n = 3; triple blockade, n = 3). (B,C,E-F) P values were calculated using 1-way ANOVA for Dunnett multiple-comparisons test. (G-H) AP only buffer inhibits complement activity. CM12 sera on PIGAKO in GVB++ (G) or MgEGTA (AP only buffer with 13 mM Mg2+) (H) with or without inhibitors. (I) Example tracing of acute CM-TMA CM03 (FHAA) on CD46KO with or without inhibitors. (J) Example tracing of remission CM-TMA no mutation CM01 on CD46KO with addition of iptacopan (FBi; 1.5 μM). (K) Example tracing of CM13 on CD46KO with addition of “triple AP blockade” including with FDi (1 μM), FBi (1.5 μM), and compstatin (18 μM). (L) Example tracing of C3 glomerulopathy (C3G) with VUS in CD46 on CD46KO. Activity persists despite C3 being below limit of detection at time sample was collected (<15 mg/dL). Data plotted as mean ± SD for each triplicate. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ns, not significant; RLU, relative luminescence units.

Example CM-TMA tracings and summary of relative luminescence and blocking. (A,D) CM02 sera on CD46KO cells (A) or PIGAKO cells (D) in GVB++ with or without heat inactivation (HI), eculizumab (ecu; 50 μg/mL), sutimlimab (sut; 30 μg/mL), or ACH-5548 (FDi). (B,E) Summary of relative 1-hour luminescence of healthy controls (HC), CM-TMA (acute or remission) with or without the addition of ecu, sut, ACH-4471/ACH-5548 (FDi; 1 μM), iptacopan (FBi; 1.5 μM), or “triple AP blockade” with FDi (1 μM), FBi (1.5 μM), and compstatin (18 μM) on CD46KO (B) or PIGAKO (E) (PIGAKO: HC, n = 18; acute TTP, n = 6; acute CM-TMA, n = 5; remission, n = 14; CM-TMA + ecu, n = 12; CM-TMA + sut, n = 11; CM-TMA + FDi, n = 11; CD46KO: HC, n = 18; acute TTP, n = 6; acute CM-TMA, n = 5; remission CM-TMA, n = 13; CM-TMA + ecu, n = 8; CM-TMA + sut, n = 8; CM-TMA + FDi, n = 7; CM-TMA FBi, n = 3; CM-TMA triple blockade, n = 3). Graphed as mean ± SD. Yellow fill indicates sample with pathogenic variant or variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in complement regulatory protein. Dashed line represents the 15th percentile of healthy control. (C,F) Relative 1-hour luminescence recovery after addition of inhibitor calculated at 1 hour as follows: (luminescence inhibitor-treated serum − luminescence untreated serum)/(luminescence heat-inactivated serum − luminescence untreated serum); (PIGAKO, n = 10 for each condition; CD46KO: CM-TMA + ecu, n = 12; CM-TMA + sut, n = 9; CM-TMA + FDi, n = 8; CM-TMA + FBi, n = 3; triple blockade, n = 3). (B,C,E-F) P values were calculated using 1-way ANOVA for Dunnett multiple-comparisons test. (G-H) AP only buffer inhibits complement activity. CM12 sera on PIGAKO in GVB++ (G) or MgEGTA (AP only buffer with 13 mM Mg2+) (H) with or without inhibitors. (I) Example tracing of acute CM-TMA CM03 (FHAA) on CD46KO with or without inhibitors. (J) Example tracing of remission CM-TMA no mutation CM01 on CD46KO with addition of iptacopan (FBi; 1.5 μM). (K) Example tracing of CM13 on CD46KO with addition of “triple AP blockade” including with FDi (1 μM), FBi (1.5 μM), and compstatin (18 μM). (L) Example tracing of C3 glomerulopathy (C3G) with VUS in CD46 on CD46KO. Activity persists despite C3 being below limit of detection at time sample was collected (<15 mg/dL). Data plotted as mean ± SD for each triplicate. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ns, not significant; RLU, relative luminescence units.

Use of CP C1s inhibitor sutimlimab but not AP inhibitors mitigates cell-directed complement activation in CM-TMA sera

To investigate the contribution of each complement pathway, we used a selection of complement inhibitors: AP inhibitors including FDis ACH-4471 and ACH-5548, factor B inhibitor (FBi) iptacopan, and C3 inhibitor compstatin; CP inhibitor including C1s inhibitor sutimlimab; and terminal pathway inhibitor including C5 inhibitor eculizumab. Activity of these inhibitors was confirmed in the AP or CP Wieslab assays (supplemental Figure 1). The terminal pathway inhibitor eculizumab rescued the bioluminescent signal to a mean of 80% on CD46KO and 87% on PIGAKO (Figure 2C,F), but unexpectedly, AP inhibitors offered minimal protection from complement-mediated cell death. With FDi, there was a mean recovery of 8.8% on CD46KO and 6.8% on PIGAKO (Figure 2A-G,I). This was confirmed with a FBi on a limited number of samples (Figure 2B-C,J). In contrast, the CP inhibitor sutimlimab offered significant protection and was comparable with eculizumab with a mean recovery of 73% on CD46KO and 78% on PIGAKO (Figure 2C,F). The sutimlimab findings were confirmed by using GVB-MgEGTA, a buffer permissive of only AP, which also blocked the serum cytolytic activity (Figure 2G-H). These effects were consistently observed in both acute and remission samples, regardless of the presence of an AP variant (compare Figure 2A-B,E,I,K). Furthermore, pathologic complement activation in sera from patients with variants in membrane bound regulators (eg, CD46) was blocked by sutimlimab but not AP inhibitors in both acute and remission samples (Figure 2A,D,G). “Triple” AP blockade targeting FB, FD, and C3 did not offer significant protection (Figure 2B-C,K). Finally, the sera of a patient with C3 glomerulopathy (Supplemental Table 2) with undetectable C3 (<15 mg/dL) showed reduced bioluminescence comparable with CM-TMA (Figure 2L). Given that complement activity persists with either C3 depletion or triple AP blockade, the “C3 bypass mechanism” may lead to membrane attack complex deposition. This supports the observations of others that, in the presence of strong CP stimulus on membrane surfaces, there is a more limited role for AP amplification.29,30 Highlighting the membrane-directed nature of the CP stimulus, heat-aggregated IgG, a well-documented fluid-phase CP activator, protects cells from death in a dose-dependent manner (supplemental Figure 2). Furthermore, this exemplifies the important differences between fluid-phase analysis and assays of membrane-directed activation.31,32

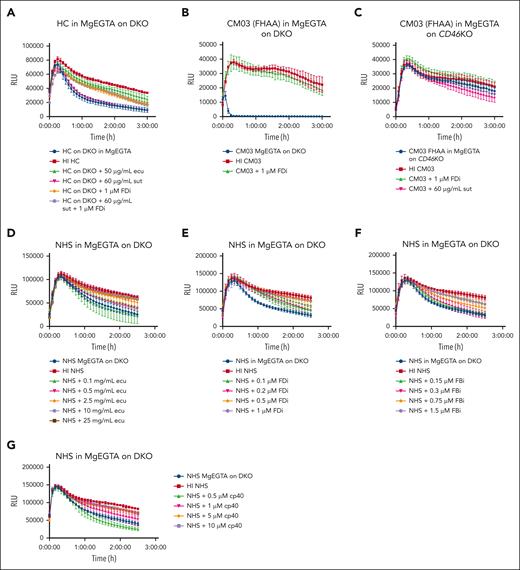

Isolated AP evaluation

Healthy control sera in AP buffer (GVB-MgEGTA) on the DKO line showed that the cytolytic effects of the AP can be isolated and appropriately blocked by FDi but not by sutimlimab (Figure 3A), and there was dose-dependent inhibition of this activity with increasing concentrations of eculizumab, FDi, FBi, and C3 inhibitor (cp40) (Figure 3D-G). Further evaluation of sera from CM03 with a known FHAA level of 57 104 arbitrary units (<200 AU normal) in isolated AP buffer showed significant killing of the DKO cell line (Figure 3B), but cytolytic activity was completely inhibited on the CD46KO cell line (Figure 3C). Importantly, although “all pathway” buffer investigations on the same sample showed the highest degree of blockade with a FDi (27.7%; Figure 2I) among acute CM-TMA samples, this was still less far less than blockade with sutimlimab (98.6%). These results emphasize the relative strength of the CP and AP of complement; that is, the CP has cytolytic activity even on cells with intact regulators, whereas the cytolytic effects in AP buffer are observed only after rendering the cells almost completely devoid of complement regulators (ie, the DKO). Taken together, these results demonstrate the importance of a CP stimulus and suggest that the AP plays a more important role in amplification rather than initiation of CM-TMA.23,33

AP assessment. (A-F) Assay in AP only buffer (13-mM MgEGTA in GVB0) on DKO cells (A-B,D-F) or CD46KO cells (C). (A) DKO cells were resuspended in MgEGTA with subsequent addition of healthy control serum with or without the addition of eculizumab, sutimlimab, FDi (ACH-5548), or a combination of sutimlimab and FDi. (B-C) Serum from CM03, patient with known FHAA titer of 57 104 AU in AP buffer on either DKO cells (B) or CD46KO cells (C) with or without the addition of FDi or sutimlimab. (D-G) Isolated AP inhibitor titrations. Pooled normal human serum (NHS) from complement technologies was incubated with increasing concentrations of eculizumab (D), FDi (ACH-5548) (E), FBi (iptacopan) (F), or C3 inhibitor (cp40) (G) in AP buffer on DKO cells. Example traces plotted as mean ± SD for each triplicate. RLU, relative luminescence units.

AP assessment. (A-F) Assay in AP only buffer (13-mM MgEGTA in GVB0) on DKO cells (A-B,D-F) or CD46KO cells (C). (A) DKO cells were resuspended in MgEGTA with subsequent addition of healthy control serum with or without the addition of eculizumab, sutimlimab, FDi (ACH-5548), or a combination of sutimlimab and FDi. (B-C) Serum from CM03, patient with known FHAA titer of 57 104 AU in AP buffer on either DKO cells (B) or CD46KO cells (C) with or without the addition of FDi or sutimlimab. (D-G) Isolated AP inhibitor titrations. Pooled normal human serum (NHS) from complement technologies was incubated with increasing concentrations of eculizumab (D), FDi (ACH-5548) (E), FBi (iptacopan) (F), or C3 inhibitor (cp40) (G) in AP buffer on DKO cells. Example traces plotted as mean ± SD for each triplicate. RLU, relative luminescence units.

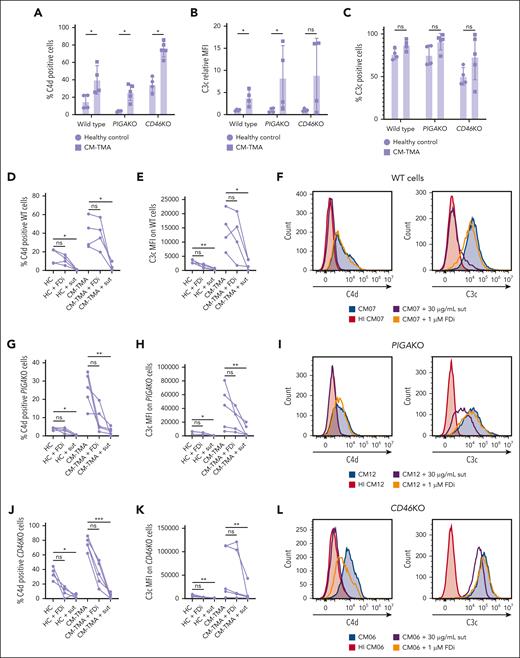

CP stimulus drives C4d deposition in CM-TMA even on WT HEK293, TF-1, and HMEC-1 cells, and MCP/CD46, as opposed to CD55, is a more significant regulator of that stimulus

Of the membrane-associated complement regulators, only variants in MCP (CD46) and factor H are associated with CM-TMA.6,34 In addition to AP regulation, these proteins are C4b-binding proteins and regulate CP activity with variable efficiency depending upon the model system and degree of sensitization.35-39 Aside from CR1, they are the only membrane-associated regulators with cofactor activity to control CP-stimulated C4b deposition on the cell surface.26,37 DAF (CD55) regulates deposition of both CP and AP convertases but possesses only decay accelerator activity.6,40

To study the role of CD46 and CD55 in CM-TMA, we performed flow cytometry to assess C3c and C4d deposition in CM-TMA compared with healthy control sera (Figure 4). Eculizumab was used to preserve cell viability. Given that CD59 inhibits only membrane attack complex insertion (ie, downstream of C3c and C4d deposition), differential deposition on WT, PIGAKO, and CD46KO will be driven by either the lack of DAF/CD55 (for PIGAKO line) or MCP/CD46 (for CD46KO line). As shown in Figure 4A-C, there is an increased C3c and C4d in CM-TMA compared with healthy controls across all 3 cell lines. The significant change in bioluminescence on the CD46KO line in samples from CM-TMA, compared with the relative absence of change in healthy control samples, supports differential regulation of the CP in CM-TMA and identifies the specificity of the CD46KO line for this disease. The critical role of CP vs AP control was further confirmed by examining the ability of sutimlimab or FDi (ACH-5548) to control either C3 or C4 deposition. Across all cell lines, both C3 and C4 are more consistently blocked by sutimlimab than FDi, suggesting a critical role for the CP (Figure 4D-L). These findings were also confirmed on WT TF-1 cells, the cell line used for the traditional mHam, by flow cytometry (supplemental Figure 3) and HMEC-1 microvascular endothelial cells by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy (supplemental Figures 4 and 5). Furthermore, the changes in complement deposition pattern (increased C4d and C3c) are consistent between WT cells and the knockout cell lines lacking complement regulators. In summary, these results suggest CD46 is more important than CD55 in the regulation of the CP in CM-TMA, and this assay identifies a physiologic stimulus inherent to the disease as opposed to creating an artifactual finding.

C4d and C3c deposition and inhibition in HC and CM-TMA samples. (A-L) All experiments were done in the presence of C5 inhibitor, eculizumab (100 μg/mL). WT, PIGAKO, or CD46KO cells were treated with 20% serum in GVB++ for 30 minutes and then stained singly for either C4d or C3c and deposition quantified by flow cytometry. The same healthy control (n = 4) and CM-TMA (n = 4 for WT; n = 5 for PIGAKO and CD46KO) were used across all cell types. Serum was treated, as indicated, with the sut (30 μg/mL) or ACH-5548 (1 μM; FDi). (A) Comparison of C4d deposition across cell types by percent positive cells determined by gating on heat-inactivated HC sample. (B) Relative median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of C3c deposition induced by CM-TMA serum vs healthy control serum. (C) Comparison of C3c deposition across cell types by percent positive cells determined by gating on heat-inactivated HC sample. (A-C) Intra–cell line differences between HC and CM-TMA P values were calculated with unpaired Mann-Whitney test. (D,G,J) C4d deposition on WT cells (D), PIGAKO (G), and PIGAKO (J) in HC or CM-TMA with or without addition of sut or FDi. (E,H,K) C3c MFI on WT cells (D), PIGAKO (G), PIGAKO (J) in HC or CM-TMA with or without addition of sutimlimab or FDi. (D-E,G-H,J-K) P values calculated using Friedman test for Dunn multiple comparisons. (F) Example histograms of CM07 on WT cells with or without HI, sut, or FDi. (I) Example histograms of CM12 on PIGAKO cells with or without HI, sut, or FDi. (L) Example histograms of CM06 on CD46KO cells with or without HI, sut, or FDi. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ns, not significant.

C4d and C3c deposition and inhibition in HC and CM-TMA samples. (A-L) All experiments were done in the presence of C5 inhibitor, eculizumab (100 μg/mL). WT, PIGAKO, or CD46KO cells were treated with 20% serum in GVB++ for 30 minutes and then stained singly for either C4d or C3c and deposition quantified by flow cytometry. The same healthy control (n = 4) and CM-TMA (n = 4 for WT; n = 5 for PIGAKO and CD46KO) were used across all cell types. Serum was treated, as indicated, with the sut (30 μg/mL) or ACH-5548 (1 μM; FDi). (A) Comparison of C4d deposition across cell types by percent positive cells determined by gating on heat-inactivated HC sample. (B) Relative median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of C3c deposition induced by CM-TMA serum vs healthy control serum. (C) Comparison of C3c deposition across cell types by percent positive cells determined by gating on heat-inactivated HC sample. (A-C) Intra–cell line differences between HC and CM-TMA P values were calculated with unpaired Mann-Whitney test. (D,G,J) C4d deposition on WT cells (D), PIGAKO (G), and PIGAKO (J) in HC or CM-TMA with or without addition of sut or FDi. (E,H,K) C3c MFI on WT cells (D), PIGAKO (G), PIGAKO (J) in HC or CM-TMA with or without addition of sutimlimab or FDi. (D-E,G-H,J-K) P values calculated using Friedman test for Dunn multiple comparisons. (F) Example histograms of CM07 on WT cells with or without HI, sut, or FDi. (I) Example histograms of CM12 on PIGAKO cells with or without HI, sut, or FDi. (L) Example histograms of CM06 on CD46KO cells with or without HI, sut, or FDi. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ns, not significant.

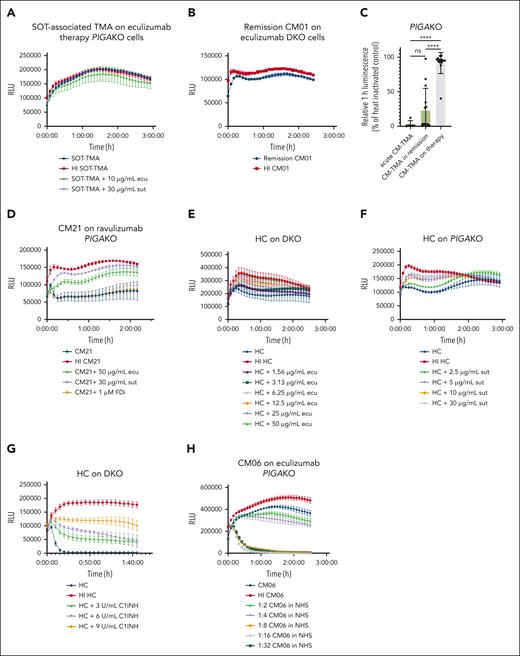

PIGAKO and DKO biosensors can be used to identify patients who may benefit from increased dosing of C5 inhibitors or C1-INH

There are no standardized assays to evaluate membrane surface protection with the use of complement inhibitors.41-44 The ability of the PIGAKO and DKO lines to identify a range of “normal” complement activity means these biosensors are potentially useful in monitoring therapeutic complement blockade. As shown in Figure 5A-B, when on therapeutic complement inhibition, patient serum yields similar cell killing to that of heat-inactivated samples on both the PIGAKO and DKO lines. Evaluating 14 samples from patients on eculizumab or ravulizumab showed an average 1-hour relative luminescence of 91.7% (95% CI, 82.9-100.4), with only 1 patient with relative luminescence <88% (CM21 at 40.3%; Figure 5C). Addition of either sutimlimab or eculizumab (but not FDi) to CM21 sera shows that additional cell protection could be offered by increasing complement inhibition (Figure 5D). We also confirmed a dose-dependent response for CP inhibitors for sutimlimab, eculizumab, and C1 inhibitor (Figure 5E-G). Finally, we show that patient sera can be diluted with NHS to give a “titer” required to overcome the complement inhibition and show an activating stimulus even when on complement inhibitor therapy (Figure 5H).

PIGAKO and DKO can be used to monitor therapeutic complement inhibition. (A) Example tracing of solid organ transplant-associated (SOT) TMA sample on therapeutic eculizumab ran on PIGAKO cells with or without addition of sutimlimab or eculizumab. (B) Example tracing of CM01 remission sample after being started on eculizumab on DKO cells. (C) Summary of relative luminescence at 1 hour for CM-TMA samples (n = 14) on treatment with C5 inhibition (acute and remission samples off treatment included for comparison). (D) Example tracing of CM21 on ravulizumab therapy with or without the addition of eculizumab, sutimlimab, or FDi on PIGAKO cells. (E) Example tracing of HC on DKO with increasing concentrations of eculizumab. (F) Example tracing of HC on PIGAKO with increasing concentrations of sutimlimab. (G) Example tracing of HC on DKO with increasing concentrations of C1 inhibitor. (H) Serum from acute CM-TMA sample (CM06) on eculizumab therapy was diluted with pooled normal human serum on PIGAKO. For panels A-B,D-H, example tracings plotted as mean ± SD for each triplicate. For panel C, P values were calculated using 1-way ANOVA for Dunnett multiple-comparisons test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ns, not significant; RLU, relative luminescence units.

PIGAKO and DKO can be used to monitor therapeutic complement inhibition. (A) Example tracing of solid organ transplant-associated (SOT) TMA sample on therapeutic eculizumab ran on PIGAKO cells with or without addition of sutimlimab or eculizumab. (B) Example tracing of CM01 remission sample after being started on eculizumab on DKO cells. (C) Summary of relative luminescence at 1 hour for CM-TMA samples (n = 14) on treatment with C5 inhibition (acute and remission samples off treatment included for comparison). (D) Example tracing of CM21 on ravulizumab therapy with or without the addition of eculizumab, sutimlimab, or FDi on PIGAKO cells. (E) Example tracing of HC on DKO with increasing concentrations of eculizumab. (F) Example tracing of HC on PIGAKO with increasing concentrations of sutimlimab. (G) Example tracing of HC on DKO with increasing concentrations of C1 inhibitor. (H) Serum from acute CM-TMA sample (CM06) on eculizumab therapy was diluted with pooled normal human serum on PIGAKO. For panels A-B,D-H, example tracings plotted as mean ± SD for each triplicate. For panel C, P values were calculated using 1-way ANOVA for Dunnett multiple-comparisons test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ns, not significant; RLU, relative luminescence units.

IgM is the immunoglobulin species contributing to CM-TMA complement activation

Finding a predominant role for CP, we hypothesized this stimulation would be mediated by immunoglobulin. We used the cleavage of IgG with IdeS (supplemental Figure 6) or selective reduction of IgM with 3-mM DTT to investigate the contributions of IgG or IgM, respectively. IdeS is an IgG-specific endopeptidase that cleaves human IgG into F(ab′)2 and Fc fragments; although F(ab’)2 is still available to bind to antigen, the loss of the complement-fixing Fc domain prohibits IgG-mediated complement activity.45 DTT treatment is commonly used to differentiate IgG from IgM-mediated pathologic effects.46-48 We confirmed DTT treatment causes a selective reduction of IgM with minimal effect on IgG using a nonreduced, unheated sodium dodecyl suflate–polyacrylamide gel electropheresis (SDS-PAGE) gel (Figure 6A) and showed dose-dependent effects on complement inhibition in healthy control sera (supplemental Figure 7). Given that DTT has nonspecific effects on complement activation,49 we also performed fractionated antisera (principally IgG) sensitization of sheep erythrocytes followed by quantification of CH50, with or without the presence of DTT. Under these conditions, there was an average CH50 reduction of ∼35% at either pretreatment (3-mM DTT) or final concentrations of DTT (0.6-mM DTT) used in the bioluminescent mHam (supplemental Table 1). Additionally, demonstrating the strength of the assay in understanding complement activation pathways relevant to an individual’s disease presentation, we identified a patient with acute fatty liver of pregnancy and hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets (HELLP) (supplemental Table 2) in whom activation is blocked with heat or eculizumab but not sutimlimab or DTT (Figure 6B). Taken together, these results demonstrate that DTT inhibitory effect in the assay is driven principally by the reduction of IgM as opposed to nonspecific effects on serum or complement.

Serum treatment with DTT or IdeS and protein G spin columns identify IgM as the predominant immunoglobulin species leading to complement activation. (A) Nonreducing, no heat SDS-PAGE gel of IgG and IgM with increasing concentrations of DTT. IgG (3 μg), IgM (3 μg), or both were incubated with DTT (0 mM, 0.5 mM, 1 mM, and 3 mM) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) in a final reaction volume of 10 μL at room temperature for 30 minutes. Some experimental details removed throughout legend. IgM′ represents a partially reduced form of IgM. (B) Sera from patient with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets (HELLP) with or without the addition of additional C5 inhibitor (eculizumab), sutimlimab, DTT, or FDi on PIGAKO cells. (C) CM12 sera was processed over a protein G spin column to purify IgG (protein G eluate [GE]) or isolate flow-through (protein G flow-through [GF]). GE and GF underwent centrifugal concentration (as required), desalting, and buffer exchange into PBS. Final preparation was added to healthy control sera in the bioluminescent mHam on CD46KO cells with or without IdeS treatment. (D) CM04 sera prepared as per panel C. After preparation, GF samples were treated with IdeS, DTT (3-mM pretreatment; 0.6-mM final), or sutimlimab (30 μg/mL). Final preparation per well was added to HC sera in the bioluminescent mHam on CD46KO cells. (E) Example tracing of CM04 in bioluminescent mHam on CD46KO cells with or without HI, temperature control (untreated serum heated to 37°C for 30 minutes), eculizumab, sutimlimab, IdeS pretreatment, or DTT before treatment. (F) Summary of relative luminescence at 1 hour for CM-TMA samples treated with DTT (n = 5) or IdeS (n = 5) compared with acute, remission, or eculizumab spiked samples. (G) Healthy control sera spiked with polyclonal IgM (extra 5, 10, or 20 μg per well) and run in bioluminescent mHam on CD46KO cells. (H) Healthy control sera spiked with myeloma IgM (10 μg per well), polyclonal IgM (10 μg per well), myeloma IgG1 (10 μg per well), polyclonal IgG (10 μg or 60 μg per well) and run in bioluminescent mHam on PIGAKO cells. (I) Healthy control sera spiked with polyclonal IgM (5 or 10 μg per well), polyclonal IgG (20 or 60 μg per well), myeloma IgG1 (20 μg per well), or myeloma IgM (10 μg per well) and run in bioluminescent mHam on DKO cells. (B-E,G-I) Example traces plotted as mean ± SD for each triplicate. (F) P values were calculated using 1-way ANOVA for Dunnett multiple-comparisons test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. HCh, heavy chain; LC, light chain; ns, not significant; RLU, relative luminescence units.

Serum treatment with DTT or IdeS and protein G spin columns identify IgM as the predominant immunoglobulin species leading to complement activation. (A) Nonreducing, no heat SDS-PAGE gel of IgG and IgM with increasing concentrations of DTT. IgG (3 μg), IgM (3 μg), or both were incubated with DTT (0 mM, 0.5 mM, 1 mM, and 3 mM) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) in a final reaction volume of 10 μL at room temperature for 30 minutes. Some experimental details removed throughout legend. IgM′ represents a partially reduced form of IgM. (B) Sera from patient with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets (HELLP) with or without the addition of additional C5 inhibitor (eculizumab), sutimlimab, DTT, or FDi on PIGAKO cells. (C) CM12 sera was processed over a protein G spin column to purify IgG (protein G eluate [GE]) or isolate flow-through (protein G flow-through [GF]). GE and GF underwent centrifugal concentration (as required), desalting, and buffer exchange into PBS. Final preparation was added to healthy control sera in the bioluminescent mHam on CD46KO cells with or without IdeS treatment. (D) CM04 sera prepared as per panel C. After preparation, GF samples were treated with IdeS, DTT (3-mM pretreatment; 0.6-mM final), or sutimlimab (30 μg/mL). Final preparation per well was added to HC sera in the bioluminescent mHam on CD46KO cells. (E) Example tracing of CM04 in bioluminescent mHam on CD46KO cells with or without HI, temperature control (untreated serum heated to 37°C for 30 minutes), eculizumab, sutimlimab, IdeS pretreatment, or DTT before treatment. (F) Summary of relative luminescence at 1 hour for CM-TMA samples treated with DTT (n = 5) or IdeS (n = 5) compared with acute, remission, or eculizumab spiked samples. (G) Healthy control sera spiked with polyclonal IgM (extra 5, 10, or 20 μg per well) and run in bioluminescent mHam on CD46KO cells. (H) Healthy control sera spiked with myeloma IgM (10 μg per well), polyclonal IgM (10 μg per well), myeloma IgG1 (10 μg per well), polyclonal IgG (10 μg or 60 μg per well) and run in bioluminescent mHam on PIGAKO cells. (I) Healthy control sera spiked with polyclonal IgM (5 or 10 μg per well), polyclonal IgG (20 or 60 μg per well), myeloma IgG1 (20 μg per well), or myeloma IgM (10 μg per well) and run in bioluminescent mHam on DKO cells. (B-E,G-I) Example traces plotted as mean ± SD for each triplicate. (F) P values were calculated using 1-way ANOVA for Dunnett multiple-comparisons test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. HCh, heavy chain; LC, light chain; ns, not significant; RLU, relative luminescence units.

Isolation of CM-TMA IgG with protein G spin columns, followed by addition to healthy control serum, consistently showed increased activity in the flow-through as opposed to the IgG eluate fraction (Figure 6C). Treatment of flow-through with DTT or sutimlimab partially blocks these effects, whereas IdeS treatment does not (Figure 6D). Moreover, pretreatment of CM-TMA sera with DTT but not IdeS results in almost complete blockade of observed activity (Figure 6E-F), with a mean 1-hour relative luminescence of 85.4% (mean 95% CI, 74.5-96.3) and 8.3% (mean 95% CI, 6.7-23.3) for DTT and IdeS, respectively.

We next investigated the ability of commercial preparations of polyclonal IgG, polyclonal IgM, monoclonal IgG, and monoclonal IgM to activate complement when spiked into healthy control sera across all 3 cell lines. For the DKO line, a pool of healthy control sera was selected for low basal activity. As seen in Figure 6G, polyclonal IgM cannot stimulate activation on the CD46KO line. There is a trend toward activating on the PIGAKO line (Figure 6H), but the effect is clearest on the DKO line (Figure 6I), in which there is a dose-dependent response with IgM but not monoclonal IgG/IgM or polyclonal IgG. This activation is again blocked by both eculizumab and sutimlimab (supplemental Figure 8).

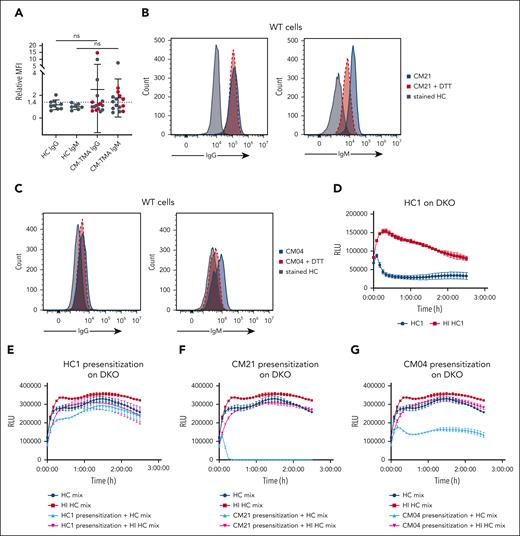

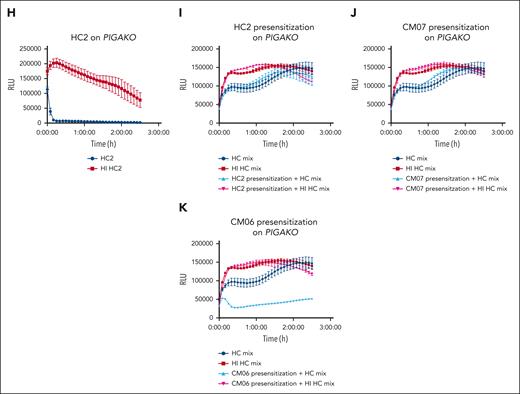

Innate, polyreactive IgM demonstrates low affinity interactions for a wide variety of substrates.50,51 The ability of polyclonal IgM and healthy control sera to activate complement on a physiologic membrane surface provides evidence that this is the culprit immunoglobulin species. However, there is a clear difference in the relative affinity of polyreactive IgM for the cell surface, even among healthy controls, as evidenced by a range of activity on the PIGAKO line from 0% to 100%; and some healthy controls show only minimal complement activity, even on the DKO cell line, but can be stimulated with the addition of polyclonal IgM preparations. Furthermore, unlike the activity observed in CM-TMA, neither healthy controls nor polyclonal IgM preparations have significant activity on the CD46KO line, suggesting a difference in total complement fixing avidity. As a preliminary evaluation of this concept, we examined the degree of IgG and IgM binding in a selection of CM-TMA and healthy control samples. There was a trend toward increased IgG and IgM staining in CM-TMA compared with healthy controls (Figure 7A). Using a relative median fluorescence intensity of >95th percentile of healthy controls (>2.05 for IgG and >1.36 for IgM) as a positive threshold, there was no difference in IgG staining (0 of 9 for HC vs 3 of 17 for CM-TMA; P ≥ .53, Fisher exact test) but significantly more positive samples for IgM in CM-TMA than HC (0 of 7 for HC vs 8 of 15 for CM-TMA; P = .0225, Fisher exact test). Furthermore, in the CM-TMA samples, increased IgM staining is more frequently seen in acute (4 of 6) than remission samples (4 of 9). Finally, IgM but not IgG staining can be reduced by treatment with DTT (Figure 7B-C).

CM-TMA sera has increased IgM binding to HEK293 cell surfaces and can presensitize cells even after HI of serum. Heat-inactivated sera was used for all cytometry and presensitization experiments to eliminate preloading of cells with C3 or C4 fragments. (A) WT cells were incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C with either heat-inactivated HC or CM-TMA sera (20% in GVB++), washed, and evaluated for deposition of IgG (HC, n = 9; CM-TMA n = 17) or IgM (HC, n = 7; CM-TMA, n = 15) by flow cytometry. Acute CM-TMA samples (n = 6) indicated by red dots. Relative MFI calculated as ratio of sample MFI compared with the average of 4 healthy controls. P values were calculated using unpaired, 2-tailed t test, with Welch correction. (B-C) Example histograms of IgG (left) or IgM (right) staining from CM21 (B) and CM04 (C) on WT cells with (red) or without (blue) pretreatment of serum with DTT (3 mM pretreatment). HC stained IgG or IgM stained cells included as baseline reference population (gray). (D) Bioluminescent mHam tracing of HC1 on DKO. (H) Bioluminescent mHam tracing of HC2 on PIGAKO. (E-G,I-K) Specially selected low activity healthy control sera mix was used to facilitate complement activity in the bioluminescent mHam after either DKO (E-G) or PIGAKO (I-K) cells were presensitized (20% heat-inactivated sera treatment for 45 minutes in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium), washed, and resuspended in GVB++ then run in the bioluminescent mHam. Baseline activity of the healthy control mix sera shown in each tracing as dark blue (HC sera mix) and dark red (HI HC sera mix). Pretreatment sera included HC1 (E), CM21 (F), CM04 (G), HC2 (I), CM07 (J), and CM06 (K). (D-K) Tracings plotted as mean ± SD for each triplicate. ns, not significant; RLU, relative luminescence units.

CM-TMA sera has increased IgM binding to HEK293 cell surfaces and can presensitize cells even after HI of serum. Heat-inactivated sera was used for all cytometry and presensitization experiments to eliminate preloading of cells with C3 or C4 fragments. (A) WT cells were incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C with either heat-inactivated HC or CM-TMA sera (20% in GVB++), washed, and evaluated for deposition of IgG (HC, n = 9; CM-TMA n = 17) or IgM (HC, n = 7; CM-TMA, n = 15) by flow cytometry. Acute CM-TMA samples (n = 6) indicated by red dots. Relative MFI calculated as ratio of sample MFI compared with the average of 4 healthy controls. P values were calculated using unpaired, 2-tailed t test, with Welch correction. (B-C) Example histograms of IgG (left) or IgM (right) staining from CM21 (B) and CM04 (C) on WT cells with (red) or without (blue) pretreatment of serum with DTT (3 mM pretreatment). HC stained IgG or IgM stained cells included as baseline reference population (gray). (D) Bioluminescent mHam tracing of HC1 on DKO. (H) Bioluminescent mHam tracing of HC2 on PIGAKO. (E-G,I-K) Specially selected low activity healthy control sera mix was used to facilitate complement activity in the bioluminescent mHam after either DKO (E-G) or PIGAKO (I-K) cells were presensitized (20% heat-inactivated sera treatment for 45 minutes in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium), washed, and resuspended in GVB++ then run in the bioluminescent mHam. Baseline activity of the healthy control mix sera shown in each tracing as dark blue (HC sera mix) and dark red (HI HC sera mix). Pretreatment sera included HC1 (E), CM21 (F), CM04 (G), HC2 (I), CM07 (J), and CM06 (K). (D-K) Tracings plotted as mean ± SD for each triplicate. ns, not significant; RLU, relative luminescence units.

Presensitization of PIGA or DKO cells with CM-TMA sera and then assessing ability to cause activation in healthy control sera demonstrates cell-bound IgM alone is sufficient to stimulate complement activation

As a final method to explore the differential complement-fixing avidity of CM-TMA sera, we presensitized either DKO or PIGAKO cells with the heat-inactivated CM-TMA or healthy control sera. The cells were washed and then incubated with healthy control sera (as a source of complement). As shown in Figure 7 (and supplemental Figure 9), presensitization with acute CM-TMA serum (n = 2) significantly increased the complement activity of the healthy control sera, whereas only 1 of 7 CM-TMA remission samples similarly tested was positive. The positive remission sample was CM21, which also had incomplete blockade on ravulizumab. Along with the trend of increased IgM binding in acute compared with remission CM-TMA samples (vide supra, Figure 6), these results suggest a shift in the IgM pool in the acute setting of CM-TMA that resolves once in remission. Importantly, given the heat inactivation, washing, and use of healthy control serum in the assay, this also demonstrated that IgM alone was sufficient to stimulate pathologic complement activity in some cases of CM-TMA. Together, these results suggest a role for both “natural, polyreactive” and “autoreactive” IgM in the disease.52

Discussion

We have developed complement biosensors capable of detecting surface-directed complement activation in real time. In contrast to fluid-phase markers of complement (soluble C5b-9, Bb, or Ba), cell-directed complement activation is more specific to CM-TMA disease pathogenesis.10,11,31 These biosensors are unique among complement diagnostics in that they allow for the detection of a range of complement activity without antibody sensitization53,54 or cell stimulation,11 allowing for an easy discrimination of activity coming from patient serum.

Since 1974, depression of C3 more than C4 in CM-TMA has been noted, and even at that time, in accordance with our own observations, it was shown that the “C3-splitting activity” was greater in all pathway buffer, suggesting a CP stimulus.55 A CP stimulus from a polyreactive IgM profile provides a mechanistic explanation for disease activity in those without variants in complement regulatory proteins and the variable penetrance of the disorder in carriers of known pathogenic variants. It also explains the common propensity for C1q, C4d, and IgM deposition in histologic specimens of TMA, including deltoid skin biopsies.56-65 These tissue findings contrast with what is seen in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) plasma, in which C3 is depressed in ∼22% to 32% of samples compared with only 6.7% for C4.66 The reason for a higher incidence of low C3 is likely explained by the role of C4 as a complement-initiating protein vs C3 as an amplifying protein; this is confirmed in quantitative radioisotopic studies, which show that, after CP stimulus, 30× more molecules of C3 than C4 are deposited on the cell surface.67 Prior studies have shown that 80% of complement activity comes from alternative amplification on a solid surface.68,69 Our assay data showing ongoing CP activity even in a patient with C3 depletion as well as activity with triple AP blockade provide further evidence that, in the face of overwhelming CP stimulus, the role of AP amplification is less significant .29,30,70

aHUS has previously been implicated as an autoimmune disease with a role for autoreactive antibodies.71-73 Leung et al implicate anti–endothelial cell antibodies in causing complement-mediated cytolysis in the disorder.71 More importantly, their data provide additional evidence that the CP stimulus is relevant to endothelial surfaces in CM-TMA. In contrast to our data, they implicate both IgG and IgM in endothelial injury, which cannot be entirely excluded by our studies on HEK293 cells that have a different repertoire of cell-surface antigens. Similar findings in the traditional mHam/TF-1 cell line again suggest the generalizability of these findings across cell surfaces and reinforce that the stimulus is not directed at a specific cell epitope but rather driven by low affinity, polyreactive interactions.

Our study highlights many important observations on the role of complement and IgM in disease pathophysiology. Although most literature focuses on their role as AP regulators, there is also evidence that FH and CD46 mitigate CP activity.35-39,74-76 Our data suggest that, in CM-TMA, the role of CD46 in regulating classical activity is more important than its role in controlling the amplification loop. Interestingly, in C3 glomerulopathy, another disorder characterized by AP variants, the disease can rarely present or even transition from dense deposit disease with predominantly C3-containing deposits to immune complex deposits.77-79 There is also well-known interplay between polyreactive IgM and FH. In mice, FH is suspected of functioning more akin to CR1 in primates and has been shown to be crucial for controlling immune complex injury in the glomerulus.80,81 Furthermore, FH deficiency in mice exacerbates the ability of polyclonal and monoclonal IgM recognizing phospholipids to deposit on kidney mesangial cells, leading to complement activation and cell damage.82 In human studies, low C4 and elevated C4d in an aHUS cohort with FHAA correlated with anemia and IgM on kidney biopsy.60

Our study has several limitations including underrepresentation of pathogenic variants (∼25%-38% in our study compared with 40%-60% in larger cohorts) and low representation of those with factor H variants in particular. Larger studies are needed for validation and to correlate ongoing positivity in the assay with relapse- and nonrelapse-related outcomes. As an added caveat, because fluid-phase and membrane-directed complement activation likely lie on a spectrum, the diagnostic accuracy of the test could be decreased in cases of strong fluid-phase activation, leading to complement depletion.

In summary, our data reveal that CM-TMA is a multihit disease with a CP stimulus, addressing the mystery of why 40% of CM-TMA lack complement-specific variants or autoantibodies. We demonstrate this finding even in patients with pathogenic variants in cell-surface complement regulators such as MCP (CD46). Variants in complement regulatory genes (FH, CD46, FB, C3, and FI) lower the threshold for disease but are not necessary or sufficient to cause disease. CP activation in the disease is at least partially driven by polyreactive or autoreactive IgM and is readily inhibited by DTT or inhibition at C1s or C5. Lastly, we show that the bioluminescent mHam provides a rapid assay to help distinguish CM-TMA from TTP and can be used to monitor CP or AP complement inhibition.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank S. Peter Howard (University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada) for gracious donation of the proaerolysin used in this study and Alexion Pharmaceuticals (Boston, MA) for generously providing both FDis, ACH-4471 and ACH-5548. Graphical illustrations were created with BioRender and Adobe Illustrator.

M.A.C. was supported by the J. Mario Molina Physician-Scientist Scholarship and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) T32 Training Program in Hematology (T32HL007525). This work was funded by the NIH, NHLBI (grant R56HL133113) and the US Department of Defense (grant W81XWH2110898).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Authorship

Contribution: M.A.C. designed research, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; N.R. performed research and wrote the paper; G.F.G. designed research and wrote the paper; D.F.-G. performed research; X.-Z.P. performed research; G.M. helped plan microscopy experiments, analyzed data, and edited the paper; S.C. reviewed research data and wrote/edited the paper; C.J.S. reviewed research data and wrote/edited the paper; K.R.M. reviewed data and wrote/edited the paper; and R.A.B. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.A.C. served on the advisory board of Alexion Pharmaceuticals and holds individual stock in AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, and Omeros Pharmaceuticals. G.F.G. serves on advisory boards of Apellis Pharmaceutical and Alexion Pharmaceuticals. C.J.S. reports research support from Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp and Alnylam Pharmaceuticals; honoraria for serving on data safety monitoring board for Alexion Pharmaceuticals and Omeros Corporation; and consulting fees from DiscMedicine and Q32 Bio. S.C. reports consultancy or advisory board fees from Alexion, Sanofi, Takeda, Sobi, and Sanofi. K.R.M. reports consultancy or advisory board fees from Sanofi, Novartis, and Sobi. M.A.C. and R.A.B. are pursuing patents/diagnostic licensing of technology reported in this manuscript. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Robert A. Brodsky, Division of Hematology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 720 Rutland Ave, Ross Research Building, Room 1025, Baltimore, MD 21205; email: brodsro@jhmi.edu.

References

Author notes

Material, data sets, and protocols are available with completion of MTA as appropriate; requests should be made to the corresponding author, Robert A. Brodsky (brodsro@jhmi.edu). No DNA/RNA sequencing data was generated.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![Serum treatment with DTT or IdeS and protein G spin columns identify IgM as the predominant immunoglobulin species leading to complement activation. (A) Nonreducing, no heat SDS-PAGE gel of IgG and IgM with increasing concentrations of DTT. IgG (3 μg), IgM (3 μg), or both were incubated with DTT (0 mM, 0.5 mM, 1 mM, and 3 mM) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) in a final reaction volume of 10 μL at room temperature for 30 minutes. Some experimental details removed throughout legend. IgM′ represents a partially reduced form of IgM. (B) Sera from patient with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets (HELLP) with or without the addition of additional C5 inhibitor (eculizumab), sutimlimab, DTT, or FDi on PIGAKO cells. (C) CM12 sera was processed over a protein G spin column to purify IgG (protein G eluate [GE]) or isolate flow-through (protein G flow-through [GF]). GE and GF underwent centrifugal concentration (as required), desalting, and buffer exchange into PBS. Final preparation was added to healthy control sera in the bioluminescent mHam on CD46KO cells with or without IdeS treatment. (D) CM04 sera prepared as per panel C. After preparation, GF samples were treated with IdeS, DTT (3-mM pretreatment; 0.6-mM final), or sutimlimab (30 μg/mL). Final preparation per well was added to HC sera in the bioluminescent mHam on CD46KO cells. (E) Example tracing of CM04 in bioluminescent mHam on CD46KO cells with or without HI, temperature control (untreated serum heated to 37°C for 30 minutes), eculizumab, sutimlimab, IdeS pretreatment, or DTT before treatment. (F) Summary of relative luminescence at 1 hour for CM-TMA samples treated with DTT (n = 5) or IdeS (n = 5) compared with acute, remission, or eculizumab spiked samples. (G) Healthy control sera spiked with polyclonal IgM (extra 5, 10, or 20 μg per well) and run in bioluminescent mHam on CD46KO cells. (H) Healthy control sera spiked with myeloma IgM (10 μg per well), polyclonal IgM (10 μg per well), myeloma IgG1 (10 μg per well), polyclonal IgG (10 μg or 60 μg per well) and run in bioluminescent mHam on PIGAKO cells. (I) Healthy control sera spiked with polyclonal IgM (5 or 10 μg per well), polyclonal IgG (20 or 60 μg per well), myeloma IgG1 (20 μg per well), or myeloma IgM (10 μg per well) and run in bioluminescent mHam on DKO cells. (B-E,G-I) Example traces plotted as mean ± SD for each triplicate. (F) P values were calculated using 1-way ANOVA for Dunnett multiple-comparisons test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. HCh, heavy chain; LC, light chain; ns, not significant; RLU, relative luminescence units.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/144/24/10.1182_blood.2024025850/2/m_blood_bld-2024-025850-gr6.jpeg?Expires=1769851012&Signature=JZBYtxMiENm1V7eYlIWB2uJrVzOlva~1DGy1RARNVZhsUPb7SSPq22UUw7hyoCj7TAi1cS-J1TNrBZXYqpUqnmgBlMIg9qrISq5zRRhmUWp5k7CN6dXAXOetgi7aE-niyU-RD4V3grP~aR6YSfPvTEhWzKAEJPFjtiWTL3qUb1e~V911A5F7bx1JQK~inu4iVtk1Wm3EUDloMFYFDPhPFIk6CCGg1P9mqs3ZjvSKHP3X4114xy-j7MDYH9Wyhmav54JQTRQCZxh85b5S3Bk0R4XM1iiUsBK8Pr06nUFI4n1-f-PQA9nE~xk8CHwvvBr06pG~TJNxW0PzfCMeZ4dH~g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal