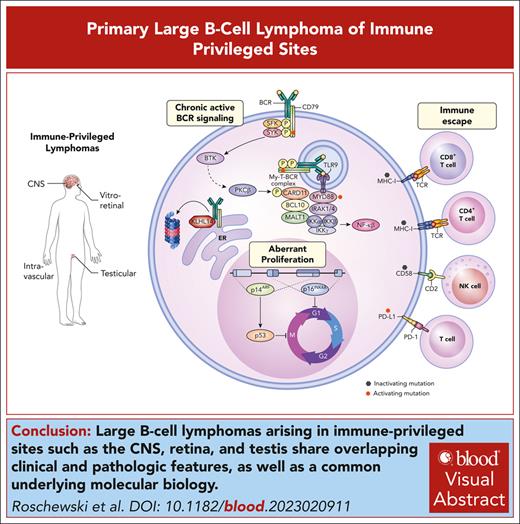

Visual Abstract

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) encompasses a diverse spectrum of aggressive B-cell lymphomas with remarkable genetic heterogeneity and myriad clinical presentations. Multiplatform genomic analyses of DLBCL have identified oncogenic drivers within genetic subtypes that allow for pathologic subclassification of tumors into discrete entities with shared immunophenotypic, genetic, and clinical features. Robust classification of lymphoid tumors establishes a foundation for precision medicine and enables the identification of novel therapeutic vulnerabilities within biologically homogeneous entities. Most cases of DLBCL involving the central nervous system (CNS), vitreous, and testis exhibit immunophenotypic features suggesting an activated B-cell (ABC) origin. Shared molecular features include frequent comutations of MYD88 (L265P) and CD79B and frequent genetic alterations promoting immune evasion, which are hallmarks of the MCD/C5/MYD88 genetic subtype of DLBCL. Clinically, these lymphomas primarily arise within anatomic sanctuary sites and have a predilection for remaining confined to extranodal sites and strong CNS tropism. Given the shared clinical and molecular features, the umbrella term primary large B-cell lymphoma of immune-privileged sites (IP-LBCL) was proposed. Other extranodal DLBCL involving the breast, adrenal glands, and skin are often ABC DLBCL but are more heterogeneous in their genomic profile and involve anatomic sites that are not considered immune privileged. In this review, we describe the overlapping clinical, pathologic, and molecular features of IP-LBCL and highlight important considerations for diagnosis, staging, and treatment. We also discuss potential therapeutic vulnerabilities of IP-LBCL including sensitivity to inhibitors of Bruton tyrosine kinase, immunomodulatory agents, and immunotherapy.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is not a singular disease but describes a broad spectrum of aggressive B-cell lymphomas that can involve any organ system in the body. As the genetic basis underlying the clinical diversity emerges,1-4 the classification of lymphoid tumors evolves with the purpose of identifying discrete DLBCL subtypes that share common immunophenotypic, genetic, and clinical features.5,6 A subset of DLBCL demonstrate a strong predilection for involving extranodal anatomic regions including immune-privileged sanctuary sites such as the central nervous system (CNS), vitreous, and testis. Furthermore, these tumors frequently remain within immune-privileged sites at the time of relapse, including the CNS, suggesting they have unique genetic and/or microenvironmental selective pressures. Recent studies have demonstrated that primary DLBCL of the CNS (PCNSL), primary DLBCL of the testis (PTL), and primary vitreoretinal lymphoma (PVRL) share biologic and clinical features.7-11 Thus, the umbrella term primary large B-cell lymphomas involving immune-privileged sites (IP-LBCL) was proposed in the fifth edition of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms.6 Importantly, the term IP-LBCL is reserved for tumors that arise in immunocompetent hosts, and DLBCL arising in the CNS or testis in the setting of inherited or acquired immunodeficiencies have a different underlying biology and are classified separately.12,13 Notably, the International Consensus Classification system also debated creating an umbrella term for “extranodal lymphoma activated B-cell (ABC) type” to describe DLBCL that arise in immune privileged sites along with other lymphomas that share clinical and biologic features including intravascular LBCL (IVLBCL), primary cutaneous DLBCL, leg-type, and primary DLBCL of the breast or adrenals.

Here, we describe the biologic and clinical features of IP-LBCL and emphasize special considerations for staging and treatment. We have included IVLBCL given its strong biologic overlap with IP-LBCL and its confinement to the intravascular niche that may also represent a site of immune privilege. We discuss therapeutic vulnerabilities of these entities and highlight clinical trials testing the efficacy of inhibitors of Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK), immunomodulatory agents, and immunotherapy.

Diagnosis and staging of IP-LBCL

IP-LBCL includes uncommon or rare lymphomas that share overlapping clinical features but with important differences (Table 1). One central unifying clinical feature is that they arise restricted to extranodal anatomic sites at diagnosis and also frequently remain within extranodal sites at relapse.14 Furthermore, these lesions either arise within the CNS or have a strong predilection for CNS progression, which can occur many years after treatment.14-16 “Immune privileged” refers to anatomic sanctuary sites such as the brain, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), eyes, and the testes based on studies that demonstrated tissue allografted into these sites was less likely to undergo graft rejection.17 Tumor cells within these immune-privileged sites are thereby postulated to be less susceptible to antitumor immune responses from T cells and natural killer cells. Given the unique clinical features of IP-LBCL, special considerations are required for diagnosis and staging that differ from nodal-based lymphomas (Table 2).

Clinical features of IP-LBCL

| . | PCNSL . | PVRL . | PTL . | IVLBCL∗ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence | ∼4% of malignant brain tumors; ∼1700 cases annually in the United States | A rare subset of PCNSL; ∼50 cases annually in United States | <5% of testicular cancers; commonest testicular malignancy in men aged >60 y | Rare |

| Age | Median age 55 to 60 y; incidence rising in those aged >70 y | Median age 50 to 60 y | Median age 65 to 68 y | Median age 60 to 70 y |

| Presentation | Focal neurologic deficits, cognitive/behavioral changes, or increased intracranial pressure | Blurry vision and floaters; impaired visual acuity; symptoms precede diagnosis for years | Firm, painless testicular mass; 40% associated with hydrocele | Fever of unknown origin common, rapid weight loss; progressive neurologic signs; hemophagocytosis-associated variant |

| Behavior | Aggressive | Indolent | Aggressive | Aggressive |

| CNS involvement | 100% | 100% involve the eye; 60%-80% progress to CNS | ∼25% relapse in CNS (can be late); most CNS progressions involve brain parenchyma | Common |

| Anatomic sites | >90% involve brain parenchyma; 30% to 40% are multifocal; 15%-25% with concurrent brain/CSF; may relapse outside of CNS | Infiltration of the vitreous; may also affect the retina | 5%-10% involve contralateral testis; 20% to 30% have concurrent disease at extranodal sites | Largely restricted to lumina of small blood vessels; the bone marrow, spleen, liver, skin, and CNS |

| . | PCNSL . | PVRL . | PTL . | IVLBCL∗ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence | ∼4% of malignant brain tumors; ∼1700 cases annually in the United States | A rare subset of PCNSL; ∼50 cases annually in United States | <5% of testicular cancers; commonest testicular malignancy in men aged >60 y | Rare |

| Age | Median age 55 to 60 y; incidence rising in those aged >70 y | Median age 50 to 60 y | Median age 65 to 68 y | Median age 60 to 70 y |

| Presentation | Focal neurologic deficits, cognitive/behavioral changes, or increased intracranial pressure | Blurry vision and floaters; impaired visual acuity; symptoms precede diagnosis for years | Firm, painless testicular mass; 40% associated with hydrocele | Fever of unknown origin common, rapid weight loss; progressive neurologic signs; hemophagocytosis-associated variant |

| Behavior | Aggressive | Indolent | Aggressive | Aggressive |

| CNS involvement | 100% | 100% involve the eye; 60%-80% progress to CNS | ∼25% relapse in CNS (can be late); most CNS progressions involve brain parenchyma | Common |

| Anatomic sites | >90% involve brain parenchyma; 30% to 40% are multifocal; 15%-25% with concurrent brain/CSF; may relapse outside of CNS | Infiltration of the vitreous; may also affect the retina | 5%-10% involve contralateral testis; 20% to 30% have concurrent disease at extranodal sites | Largely restricted to lumina of small blood vessels; the bone marrow, spleen, liver, skin, and CNS |

IVLBCL is currently categorized as a discrete biologic entity in both the World Health Organization and International Consensus Classification systems.

Diagnosis and staging of IP-LBCL

| . | PCNSL . | PVRL . | PTL . | IVLBCL . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic biopsy procedures | ||||

| Stereotactic brain biopsy | Procedure of choice | |||

| Vitreous fluid biopsy | Procedure of choice | |||

| Orchiectomy | Procedure of choice | |||

| Biopsy affected organ (the liver, bone marrow, or skin) | Procedure of choice | |||

| Random skin biopsies | Consider | |||

| Adjunctive tests (CSF or vitreous) | ||||

| Flow cytometry, cytology | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended |

| MYD88 mutation testing | Consider | Consider | Consider | Consider |

| Immunoglobulin gene rearrangement | Consider | Consider | Consider | Consider |

| ctDNA | Consider | Consider | Consider | Consider |

| Cytokines (interleukin-6, interleukin-10) | Consider | Consider | Not recommended | Not recommended |

| Laboratory tests | ||||

| Complete blood count, LDH, and liver and renal function | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended |

| HIV screening | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended |

| Hepatitis B screening | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended |

| Hepatitis C screening | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended |

| EBV serology | Recommended | Not recommended | Not recommended | Not recommended |

| Staging procedures | ||||

| MRI of brain with gadolinium | Essential | Recommended | Consider | Recommended |

| Dilated eye examination | Recommended | Essential | Not recommended | Not recommended |

| Testicular ultrasound | Consider | Consider | Essential | Not recommended |

| FDG-PET of body | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended |

| Peripheral blood flow cytometry | Not recommended | Not recommended | Consider | Consider |

| MRI of spine | Consider | Not recommended | Not recommended | Not Recommended |

| CT of body with contrast | Consider | Consider | Consider | Consider |

| Bone marrow biopsy, aspirate | Consider | Not recommended | Recommended | Recommended |

| . | PCNSL . | PVRL . | PTL . | IVLBCL . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic biopsy procedures | ||||

| Stereotactic brain biopsy | Procedure of choice | |||

| Vitreous fluid biopsy | Procedure of choice | |||

| Orchiectomy | Procedure of choice | |||

| Biopsy affected organ (the liver, bone marrow, or skin) | Procedure of choice | |||

| Random skin biopsies | Consider | |||

| Adjunctive tests (CSF or vitreous) | ||||

| Flow cytometry, cytology | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended |

| MYD88 mutation testing | Consider | Consider | Consider | Consider |

| Immunoglobulin gene rearrangement | Consider | Consider | Consider | Consider |

| ctDNA | Consider | Consider | Consider | Consider |

| Cytokines (interleukin-6, interleukin-10) | Consider | Consider | Not recommended | Not recommended |

| Laboratory tests | ||||

| Complete blood count, LDH, and liver and renal function | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended |

| HIV screening | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended |

| Hepatitis B screening | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended |

| Hepatitis C screening | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended |

| EBV serology | Recommended | Not recommended | Not recommended | Not recommended |

| Staging procedures | ||||

| MRI of brain with gadolinium | Essential | Recommended | Consider | Recommended |

| Dilated eye examination | Recommended | Essential | Not recommended | Not recommended |

| Testicular ultrasound | Consider | Consider | Essential | Not recommended |

| FDG-PET of body | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended |

| Peripheral blood flow cytometry | Not recommended | Not recommended | Consider | Consider |

| MRI of spine | Consider | Not recommended | Not recommended | Not Recommended |

| CT of body with contrast | Consider | Consider | Consider | Consider |

| Bone marrow biopsy, aspirate | Consider | Not recommended | Recommended | Recommended |

CT, computed tomography EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

PCNSL

PCNSL is a rare and aggressive B-cell lymphoma confined to the brain, spine, CSF, or eyes at diagnosis.18,19 It constitutes ∼4% of newly diagnosed malignant brain tumors, with a slight male predominance.20 The incidence of PCNSL is rising among immunocompetent people particularly in individuals aged >70 years.21,22 Notably, CNS lymphomas that arise in the setting of immunodeficiency including human immunodeficiency virus and after solid organ transplantation are commonly associated with Epstein-Barr virus, have a different genetic landscape, and are considered separate entities.12,13 The clinical presentation may be an acute onset of focal neurologic deficits or more insidious with subtle cognitive or behavioral changes that develop over weeks. The natural history is highly aggressive and neurologic symptoms often progress rapidly. PCNSL involves the brain parenchyma in >90% of cases, with most lesions being supratentorial and 30% to 40% of cases showing multiple brain lesions.23 Concomitant involvement of the CSF or eyes occurs in 15% to 25% of cases, but isolated leptomeningeal involvement is rare. PCNSL may involve anatomic sites outside of the CNS at relapse.24

Stereotactic needle biopsy of a brain parenchymal lesion is the diagnostic procedure of choice and surgical resection is not indicated. Empiric corticosteroid therapy before biopsy is strongly discouraged because it may result in the disappearance of the lesions, which is not sufficient evidence to diagnose lymphoma.25 The CSF should be evaluated with flow cytometry (preferred) and cytology in all patients unless contraindicated because of increased intracranial pressure. In cases in which biopsy is challenging, the demonstration of tumor cells in the CSF using flow cytometry or cytology can be diagnostic. MYD88 mutation and immunoglobin gene rearrangement testing in CSF can also be considered as adjunct diagnostic procedures.26 Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) can be detected in the CSF of virtually all patients and may emerge as a useful biomarker for diagnosis and/or prognosis.27 Interestingly, ctDNA can also be detected in the plasma of most patients, which may have prognostic relevance by identifying a high-risk group at diagnosis and as a noninvasive biomarker that can monitor treatment response.27

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the brain with gadolinium are essential for tumor characterization, and spine MRI can be considered in patients with localizing symptoms. Staging procedures for PCNSL focus on ruling out the presence of systemic DLBCL, and fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET) scans are the most sensitive to evaluate for extranodal disease.28 All patients should have a dilated eye examination, and a testicular ultrasound should be considered in men. Bone marrow biopsy with aspirate have limited clinical utility in the modern era with routine use of FDG-PET scans.

PVRL

PVRL is a rare variant of PCNSL in which tumor cells are confined to the vitreous or retina without overt CNS involvement.29 Patients present with the subacute onset of blurry vision, floaters, or decreased visual acuity that mimics posterior uveitis. PVRL often has an indolent course and symptoms can precede diagnosis for years. Similar to PCNSL, empiric therapy with corticosteroids may transiently improve symptoms but may delay diagnosis confirmation. The diagnosis of PVRL can be challenging and relies on a combination of immunocytochemical or flow cytometry from vitrectomy specimens. Intravitreal levels of interleukin-10 and interleukin-6 may also assist in diagnosis.30MYD88 (L265P) mutation analysis in the vitreous may aid in diagnosis but is not widely available.31 Next-generation sequencing panels for ctDNA from the vitreous are also emerging as adjunctive diagnostic tools.11,27

Ruling out CNS disease is critical and best performed with a contrasted MRI of the brain and CSF flow cytometry. Up to 80% of patients with PVRL will ultimately progress to the CNS, but systemic spread is rare. FDG-PET scans of the body are used to rule out systemic lymphomas with secondary involvement of intraocular structures; this is uncommon except for PTL and primary breast lymphoma, which can progress to the eye in isolation or with concomitant CNS relapse.32

PTL

PTL is an uncommon lymphoma, but it is the most common testicular malignancy in men aged ≥60 years.33 The classic presentation is painless testicular enlargement and a hydrocele may coexist in up to 40% of cases.34 Most cases are localized to the testis, but PTL includes cases of systemic spread that commonly remain confined to extranodal sites including the CNS, skin, lung, soft tissues, and the contralateral testis.35 The diagnostic procedure of choice is an orchiectomy. FDG-PET scans are used to rule out systemic disease and bilateral testicular ultrasounds are essential. Most PTL cases are localized at diagnosis, with up to 10% involving the contralateral testis and ∼25% of cases with systemic involvement.36 Despite the limited stage, the clinical course of PTL is aggressive and demonstrates a continuous rate of relapse.35-37 Most relapses involve extranodal sites such as the contralateral testis or CNS that can occur many years after therapy36,38 and typically involve the brain parenchyma.15 For this reason, all patients with PTL should have a lumbar puncture with CSF studies, and a contrasted brain MRI should be considered. The biologic reasons for the CNS tropism of PTL remains unclear, but a recent study suggested that tumors with BCL6 or PDL1/2 rearrangements were associated with a higher risk of CNS relapse.39 The management of patients with PTL includes measures to prevent CNS relapse, and a recent prospective study demonstrated that intensive CNS prophylaxis including both intrathecal and intravenous methods was feasible and no CNS relapses were observed.37 Contralateral testis irradiation is administered to prevent local recurrence.

IVLBCL

IVLBCL is a rare and aggressive form of extranodal DLBCL characterized by tumor cells growing predominantly within the lumen of small blood vessels without associated lymphadenopathy, although extravascular location of tumor cells has been described.40-42 The diagnosis is challenging and often delayed because imaging scans are unrevealing and biopsy of an affected organ is required. Common symptoms are nonspecific including generalized fatigue, anorexia, rapid deterioration of performance status, weight loss, night sweats, neurologic symptoms, and fever of unknown origin.43 Random skin biopsies can be diagnostic of IVLBCL in cases of fever of unknown origin with elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels, poor performance status, and unexplained cytopenias, and may avoid unacceptably prolonged delays in treatment initiation.44 The natural history of IVLBCL is very aggressive and often results in progressive neurologic compromise without therapy. Cases isolated to the skin appear to have a better prognosis, likely because of earlier diagnosis and therapeutic intervention. A hemophagocytic syndrome–associated variant has been described, which more commonly involves the bone marrow and is often associated with fever and hepatosplenomegaly.45,46 Conventional staging procedures are not reliable and IVLBCL should be considered disseminated at diagnosis. Bone marrow biopsy, brain MRI with contrast, and lumbar puncture with CSF studies are recommended.40 ctDNA levels are often very high in IVLBCL and may emerge as an effective method for studying tumor genetics and monitoring therapeutic response.47

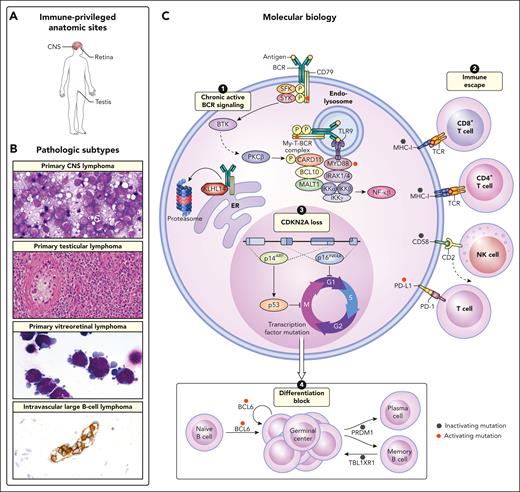

Pathologic features of IP-LBCL

Histologically, on conventional hematoxylin and eosin stains, these tumors are not unique (Figure 1). A common feature of cases presenting in the CNS and testis is the ABC or non–germinal center B-cell (non-GCB) profile using the Hans algorithm. Gene expression profiling studies are confirmatory of the ABC derivation. The tumor cells express B-cell–associated antigens including CD20, CD19, and CD79a. They are typically positive for MUM1/IRF4 but negative for CD10. BCL6 is usually positive and BCL2 is more variably expressed. Although MYC rearrangement is not a feature of these lesions, MYC protein is often positive. A common feature of DLBCL presenting in immune privileged sites is loss of expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class 1 and class 2.2 Consistent with the failure of an immune response, infiltrating immune cells including T cells are generally few in number.

Unifying clinical and biologic features of IP-LBCL and IVLBCL. (A) The involved anatomic sites are commonly restricted to extranodal regions at both diagnosis and upon relapse and include the CNS, eye, and testis. (B) The pathologic subtypes included under the proposed umbrella term IP-LBCL include primary CNS lymphoma, primary testicular lymphoma, and PVRL. IVLBCL is also an extranodal ABC lymphoma that shares features with IP-LBCL but does not arise in an anatomic site that is considered to be immune privileged. Primary CNS lymphoma, original magnification ×1000; primary testicular lymphoma, original magnification ×200; primary vitreoretinal lymphoma, original magnification ×1000; intravascular large B-cell lymphoma, original magnification ×400. (C) The molecular biology of IP-LBCL mostly closely resembles that of an ABC phenotype and the MCD genetic subtype of DLBCL. Four main biologic cornerstones that have been described in IP-LBCL include (1) activating mutations of MYD88 (L265P) and CD79B that form the MYD88-TLR9-BCR (My-T-BCR) complex and promote chronic active BCR signaling; (2) inactivating mutations of class 1 and 2 HLA expression as well as CD58, which promote immune escape; (3) loss of CDKN2A, which promotes unregulated cell cycle activation; and (4) inactivating mutations in transcription factors such as PRDM1 and TBL1XR1, that promote ongoing proliferation.

Unifying clinical and biologic features of IP-LBCL and IVLBCL. (A) The involved anatomic sites are commonly restricted to extranodal regions at both diagnosis and upon relapse and include the CNS, eye, and testis. (B) The pathologic subtypes included under the proposed umbrella term IP-LBCL include primary CNS lymphoma, primary testicular lymphoma, and PVRL. IVLBCL is also an extranodal ABC lymphoma that shares features with IP-LBCL but does not arise in an anatomic site that is considered to be immune privileged. Primary CNS lymphoma, original magnification ×1000; primary testicular lymphoma, original magnification ×200; primary vitreoretinal lymphoma, original magnification ×1000; intravascular large B-cell lymphoma, original magnification ×400. (C) The molecular biology of IP-LBCL mostly closely resembles that of an ABC phenotype and the MCD genetic subtype of DLBCL. Four main biologic cornerstones that have been described in IP-LBCL include (1) activating mutations of MYD88 (L265P) and CD79B that form the MYD88-TLR9-BCR (My-T-BCR) complex and promote chronic active BCR signaling; (2) inactivating mutations of class 1 and 2 HLA expression as well as CD58, which promote immune escape; (3) loss of CDKN2A, which promotes unregulated cell cycle activation; and (4) inactivating mutations in transcription factors such as PRDM1 and TBL1XR1, that promote ongoing proliferation.

The phenotype of IVLBCL is more heterogeneous.40 Although these tumors are often non-GCB by the Hans algorithm, CD5 is often positive, which is not generally a feature of tumors arising in the CNS or testis. Fewer data are available regarding the phenotype of vitreo-retinal lesions. The cells recovered from the vitreous are often markedly degenerate, and difficult to characterize by immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry.

IP-LBCL share molecular features with MCD DLBCL

Although histological and clinical heterogeneity of systemic DLBCL have long been appreciated, only recently have genetic studies been sufficiently powered to resolve these differences into distinct molecular subtypes. Gene expression studies first demonstrated that DLBCL consists of 2 main subtypes that share transcriptional patterns with either GCBs, so called GCB DLBCL, or with in vitro ABCs, so called ABC DLBCL. The ABC subtype was found to have high NF-κB activity and worse overall survival in response to cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP)-based therapies.48-51 This gene expression classification system, termed “cell of origin,” is an incredibly robust classification that yields greater reproducibility across tissue preparation and gene expression profiling platforms.52-54 Patients with ABCs show an enrichment for unique genomic alterations in genes including MYD88, CD79B, PIM1, and CDKN2A, among others; whereas patients with GCBs have higher mutation frequencies in EZH2, MEF2B, GNA13, BCL2, and SGK1.55-59 Subsequent functional studies have identified unique survival mechanisms used by each subtype, none perhaps as clinically relevant as the discovery of self-antigen–driven chronic active B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling in ABC DLBCL, which is sensitive to BTK inhibition.56,60 As such, since the revised fourth edition of the World Health Organization classification, studies to determine the cell of origin for newly diagnosed DLBCL have been recommended, with this guidance retained in the newer classification systems.5,6 IP-LBCL are heavily skewed to the non-GCB subtype, a histological method that approximates the ABC DLBCL cell-of-origin classification.61

More recently, genetic studies of de novo DLBCL have described upward of 8 molecular subtypes of DLBCL. Despite using different sequencing approaches and statistical methods, each of the 3 models contains highly overlapping molecular features for a given genetic subtype.1-4 Notably, MYD88 (L265P) and CD79B immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) mutations are hallmark features of the MCD/C5/MYD88 subtypes. Other MCD features are also frequently found in IP-LBCL including mutations and homozygous deletions in CDKN2A and HLA class 1 genes; evidence of somatic hypermutation targeting BTG1, BTG2, KLHL14, and PIM1; gains and amplifications in BCL2; as well as missense mutations in TBL1XR1.7,11,62-68 The MCD subtype has >30 genetic features (mutations, translocations, and DNA copy number alterations). Although the functional consequence of each have yet to be determined, many hallmarks of cancer are represented within the mutated gene list of MCD DLBCL including resisting cell death (BCL2), evading growth suppressors (CDK2NA), phenotypic plasticity (IRF4, PRDM1, SPIB, and TBL1XR1), and immune evasion (HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, TAP1, CD58, and PDCD1LG2/CD274).

Given high expression of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)/PD-L269 and the success of immune checkpoint blockade therapy in Hodgkin lymphoma,70 the observation of amplification of chromosome 9p24, containing the PD-L1/PD-L2 loci in a subset MCD and IP-LBCL cases warrants a brief discussion of checkpoint blockade in IP-LBCL. In general, PD-L1 staining is higher in ABC DLBCL than in GCB DLBCL71 and in Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL than in Epstein-Barr virus–negative DLBCL,72 however overall frequencies remain <20%.2 Within PCNSL and PTL, genetic alteration of the locus was reported in nearly 50% of cases7 and early case reports of relapsed cases of PD-L1–positive PCNSL and PTL showed high response rates to programmed death protein 1 blockade.73 Such high frequencies of PD-L1/PD-L2 have not been observed in subsequent studies8,68 and prospective clinical trials have shown disappointing results.74,75

Conversely, other genomic alterations common to IP-LBCL are clinically actionable using BTK inhibitors, namely, the co-occurrence of MYD88 (L265P) and CD79B ITAM mutations. At first blush, this appears to be a contradiction. MYD88 is an innate immune signaling adapter protein that facilitates activation of downstream NF-κB, interferon regulatory factor (IRF), and MAPK signaling, whereas CD79B is 1 of 2 immunoglobulin containing, signaling competent components of the BCR. One might predict then that BTK inhibitors would be less effective in patients with DLBCL with both MYD88 (L265P) and CD79B mutations compared with those with mutant CD79B alone because of activation of a compensatory pathway driving NF-κB. Yet, double-mutant tumors are, in fact, the most sensitive to BTK inhibitors60 and patients with MCD subtype, in general, demonstrate the greatest benefit of combining BTK inhibitors with chemotherapy.76

This apparent clinical contradiction was resolved with the discovery of the “My-T-BCR” supercomplex, named for the colocalization of MYD88 (L265P) with TLR9 and the BCR. The My-T-BCR is the site of NF-κB activation and exceptionally sensitive to BTK inhibition possibly because of autophagic degradation of mutant MYD88 by BTK inhibitors.77 The My-T-BCR complex was found in ABC and PCNSL tumors, and its presence correlated with clinical response to BTK inhibition.78 Thus, the BCR and MYD88 are not independent pathways that can activate NF-κB in MCD DLBCL but rather both proteins required to form a multiprotein supercomplex that mediates oncogenic signaling.

Other frequently mutated MCD genes may further promote this mode of signaling. For instance, KLHL14 is a Kelch-like BTB-containing subunit of the Cullin-RING E3 ligase complex. KLHL14 is localized to the cytoplasmic face of the endoplasmic reticulum in which it was recently shown to interact with CD79A, CD79B, and immunoglobulin M.79 Missense and nonsense mutations in KLHL14 are associated with MCD DLBCL, but only missense mutations were found to impair the growth of MCD DLBCL cell lines and decreased BCR expression when ectopically expressed. Conversely, mimicking KLHL14 nonsense mutations with CRISPR-mediated knockout of KLHL14 resulted in higher levels of surface BCR, increased My-T-BCR interactions, and resulted in a relative growth advantage to MCD DLBCL cell lines treated with ibrutinib. Taken together, these results implicate KLHL14 in a critical quality control mechanism of BCR expression and highlight the central role of My-T-BCR signaling to MCD-like lymphomas.

Clinical management of IP-LBCL

The clinical management of patients with IP-LBCL differs significantly when the CNS is involved compared with situations in which strategies to prevent CNS progression/relapse are considered. A thorough discussion is beyond the scope of this manuscript and is better reviewed elsewhere,18,19,80,81 but we emphasize important aspects of clinical management specific to IP-LBCL and highlight rational targeted agents being studied in PCNSL and PVRL, the prototypical MCD/C5/MYD88 tumor, because these therapies may ultimately prove clinical utility across all IP-LBCLs (Table 3).

Novel agents for relapsed or refractory IP-LBCL

| . | Study design (no. of patients) . | Response rate . | Long-term efficacy . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BTK inhibitors | ||||

| Ibrutinib | Phase 1 (N = 13) | ORR = 77%, CR = 38% | Median PFS = 4.6 mo | 102 |

| Phase 2 (N = 52) | ORR = 52%, CR = 19% | Median PFS = 4.8 mo | 103 | |

| Tirabrutinib | Phase 2 (N = 44) | ORR = 64%, CR = 34% | Median PFS = 2.9 mo | 105 |

| Immunomodulatory agents | ||||

| Lenalidomide | Phase 1 (N = 7) | ORR = 86%, CR = 14% | Not reported | 110 |

| Lenalidomide with rituximab | Phase 2 (N = 45) | ORR = 36%, CR = 29% | Median PFS = 7.8 mo | 111 |

| Pomalidomide with dexamethasone | Phase 1 (N = 25) | ORR = 48%, CR = 32% | Median PFS = 5.3 mo | 112 |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors | ||||

| Nivolumab | Phase 2 PCNSL (N = 47) | ORR = 6% | Median PFS = 1.4 mo | Clinicaltrials.gov [NCT02857426] |

| Phase 2 PTL (N = 19) | ORR = 26% | Median PFS = 1.7 mo | Clinicaltrials.gov [NCT02857426] | |

| Pembrolizumab | Phase 2 PCNSL (N = 50) | ORR = 12% | Median PFS = 2.6 mo | 75 |

| CAR T-cell therapy | ||||

| Tisangenlecleucel | Phase 1/2 (N = 12) | ORR = 58%, CR = 50% | Not reported | 113 |

| Axicabtagene ciloleucel | Phase 1 (N = 9) | ORR = 86%, CR = 86% | Not reported | 114 |

| . | Study design (no. of patients) . | Response rate . | Long-term efficacy . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BTK inhibitors | ||||

| Ibrutinib | Phase 1 (N = 13) | ORR = 77%, CR = 38% | Median PFS = 4.6 mo | 102 |

| Phase 2 (N = 52) | ORR = 52%, CR = 19% | Median PFS = 4.8 mo | 103 | |

| Tirabrutinib | Phase 2 (N = 44) | ORR = 64%, CR = 34% | Median PFS = 2.9 mo | 105 |

| Immunomodulatory agents | ||||

| Lenalidomide | Phase 1 (N = 7) | ORR = 86%, CR = 14% | Not reported | 110 |

| Lenalidomide with rituximab | Phase 2 (N = 45) | ORR = 36%, CR = 29% | Median PFS = 7.8 mo | 111 |

| Pomalidomide with dexamethasone | Phase 1 (N = 25) | ORR = 48%, CR = 32% | Median PFS = 5.3 mo | 112 |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors | ||||

| Nivolumab | Phase 2 PCNSL (N = 47) | ORR = 6% | Median PFS = 1.4 mo | Clinicaltrials.gov [NCT02857426] |

| Phase 2 PTL (N = 19) | ORR = 26% | Median PFS = 1.7 mo | Clinicaltrials.gov [NCT02857426] | |

| Pembrolizumab | Phase 2 PCNSL (N = 50) | ORR = 12% | Median PFS = 2.6 mo | 75 |

| CAR T-cell therapy | ||||

| Tisangenlecleucel | Phase 1/2 (N = 12) | ORR = 58%, CR = 50% | Not reported | 113 |

| Axicabtagene ciloleucel | Phase 1 (N = 9) | ORR = 86%, CR = 86% | Not reported | 114 |

CR, complete response rate; ORR, overall response rate.

Treatment of PCNSL

Treatment of PCNSL differs significantly from the treatment of systemic DLBCL because standard anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimens do not reliably cross the blood–brain barrier and the prognosis is worse. As such, high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX) chemotherapy regimens form the cornerstone of therapy.82-85 The rate of complete response to standard induction regimens is only ∼50%, so most patients are offered postremission consolidation. Younger patients who are deemed suitable for dose-intensive therapy are often treated with high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation.86,87 A recent randomized phase 2 study of 140 patients aged <60 years showed that thiotepa-based conditioning followed by autologous stem cell transplantation resulted in an 8-year progression-free survival (PFS) of 67% and was a superior consolidation strategy than whole-brain radiotherapy.83 Older patients and those not deemed suitable for dose-intensive therapy have a much poorer prognosis because few alternative therapies exist with reliable penetration across the blood–brain barrier.88-91 Furthermore, the actual rate of cure may not be captured from clinical trials because late recurrences are common.16,92 Few effective salvage therapies exist, and those with chemotherapy-refractory disease have a grave prognosis.93

PVRL

PVRL has an indolent course and systemic therapy is generally not indicated at diagnosis. Clinical management incorporates localized therapy to prevent progressive vision loss but this does not prevent CNS relapse.94 Treatment algorithms derive mostly from small retrospective series leading to significant variance in practice patterns.95 In situations of unilateral involvement, localized therapy consists of intravitreal injections of either MTX or rituximab.96,97 An alternative local therapy is radiotherapy, but this risks inducing retinopathy and does not prevent CNS relapse. Bilateral involvement leads to consideration of more intensive therapy such as HD-MTX, but the benefit of this approach is unknown. HD-MTX has been used after intravitreal MTX to prevent CNS relapse, but the benefit to prevention of CNS progression remains unproven. Prospective studies testing the role of novel targeted agents and immunotherapy are needed.

Treatment of PTL

Orchiectomy is required for the localized management of PTL but is not definitive therapy and systemic therapy is indicated even with limited stage disease because of the high risk of systemic relapse.34,35 Standard chemotherapy regimens for DLBCL such as rituximab plus CHOP (R-CHOP) should be given and the benefit of anthracycline-based chemotherapy has been shown.35 The management of patients with PTL includes measures to prevent CNS relapse, and a recent prospective study demonstrated that intensive CNS prophylaxis including both intrathecal and intravenous methods was feasible and no CNS relapses were observed.37 Contralateral testis irradiation is administered to prevent local recurrence.37

A common source of treatment failure for PTL is related to the risk of CNS relapse, which occurs in 15% to 30% of patients.38 Prospective studies have included intrathecal MTX as CNS prophylaxis and the rate of CNS progression was only 6%.98 Other studies have used HD-MTX as CNS prophylaxis, which may be a suitable option in some patients.99 A recent prospective study demonstrated that intensive CNS prophylaxis including both intrathecal and intravenous methods was feasible and no CNS relapses were observed.37 Involvement of the contralateral testicle occurs in up to 10% of cases, which should prompt the use of testicular radiation. Retrospective series have suggested that contralateral scrotal radiation is effective for reducing the risk of local recurrence and this strategy is recommended.35,37 Hypogonadism is a risk of this approach and testosterone replacement should be considered.

Treatment of IVLBCL

Given the challenges of accurate staging of IVLBCL, it should be considered as disseminated disease in all cases. Anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimens are the mainstay of treatment, with special attention given to the risk of CNS involvement and progression. As in IP-LBCL, the risk of CNS progression in IVLBCL is sufficiently high to warrant consideration of CNS prophylaxis as part of frontline management. A prospective phase 2 study of 38 patients with IVLBCL and no CNS involvement tested R-CHOP every 14 days with intrathecal chemotherapy alternating with rituximab plus HD-MTX as an intensive strategy to prevent CNS disease suggested that CNS prophylaxis may reduce the risk of CNS recurrence in IVLBCL.100

Novel treatment approaches for IP-LBCL

The fundamental question is whether an improved understanding of the genetic profile of IP-LBCL can be translated to improved clinical outcomes. Multiple rational targeted agents and immunotherapy approaches have been tested in PCNSL and PVRL and multiple combinations are being tested.

Ibrutinib is a first-generation BTK inhibitor that interferes with chronic active BCR signaling and initially demonstrated selective activity in relapsed or refractory DLBCL tumors that harbor both MYD88L265P and CD79B mutations.60 BTK was thereby identified as highly rational therapeutic target in PCNSL because this genetic profile is characteristic. Indeed, early clinical studies demonstrated very high response rates to ibrutinib monotherapy,101-103 but resistance developed rapidly to monotherapy,104 which results in a median PFS of only 3 to 5 months.102,103,105 To overcome the problem of acquired resistance, ibrutinib has been added to chemotherapy including HD-MTX with rituximab106 and anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimens.101 This strategy resulted in significantly higher rates of complete response, and many combination regimens using ibrutinib as well as second generation BTK inhibitors including zanubrutinib, acalabrutinib, tirabrutinib, and orelabrutinib are now being tested in ongoing clinical trials.

Understanding the potential role of BTK inhibitors across IP-LBCL subtypes is more difficult because PTL is uncommon and related entities such as IVLBCL are both uncommon and frequently excluded from clinical trials that require measurable disease. The most compelling data supporting a possible role of BTK inhibitors for IP-LBCL comes from a randomized phase 3 study testing frontline therapy of R-CHOP with ibrutinib compared with R-CHOP with placebo in non-GCB DLBCL.107 This study did not meet its primary end point and no benefit was observed with the use of ibrutinib across the entire study population. Intriguingly, patients aged <60 years had improvements in both PFS and overall survival, and a subsequent translational study demonstrated that the genetic subtypes MCD and N1 had survival of 100% when treated with ibrutinib plus R-CHOP.76

Other novel targeted agents that are rational for PCNSL and PVRL are the immunomodulatory drugs, lenalidomide and pomalidomide, which downregulate the transcription factor interferon regulatory factor 4 and augment interferon β production to kill ABC DLBCL cell lines.108,109 Both lenalidomide and pomalidomide have been tested as combination therapy for relapsed or refractory PCNSL and PVRL.110-112 These agents show clinical activity and may improve outcomes as part of combination therapy, many of which are being tested in ongoing studies.

Novel immunotherapy approaches including chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies targeting CD19 are effective in chemotherapy-refractory systemic DLBCL and have been explored in PCNSL.113,114 These early studies have demonstrated that effector CAR T cells successfully cross the blood–brain barrier and are clinically active in CNS tumors. A summary of 128 patients with CNS lymphoma treated with CAR T-cell therapy showed acceptable safety and suggested that the rates of complete response compare favorably with those in systemic DLBCL.115 Immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1 showed early promise in retrospective studies for PCNSL and PTL,73 but prospective studies have been disappointing.74,75

Conclusion and future directions

The umbrella term IP-LBCL includes cases of DLBCL that involve the CNS, vitreous, and testis, that share unique clinical features including a strong predilection to involve extranodal sites, including the CNS, and are commonly of the MCD/C5/MYD88 genetic subtype. The relevance of their origins within immune-privileged sites is unclear and other entities also appear closely related as extranodal ABC lymphomas, particularly IVLBCL. The recognition of IP-LBCL as a distinct group of tumors allows for the investigation of therapeutic vulnerabilities and clinical trials can report results within the context of these subtypes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank patients and their families who participate in clinical trials testing novel agents in aggressive B-cell lymphomas. Ethan Tyler is acknowledged for illustration support.

This work is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH: National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Authorship

Contribution: M.R wrote the first version of this manuscript with input from J.D.P. and E.S.J., who edited the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mark Roschewski, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Lymphoid Malignancies Branch, CCR 9000 Rockville Pike, Bldg 10, Room 12c442, 10 Center Dr, Bethesda, MD 20892; email: mark.roschewski@nih.gov.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal