Key Points

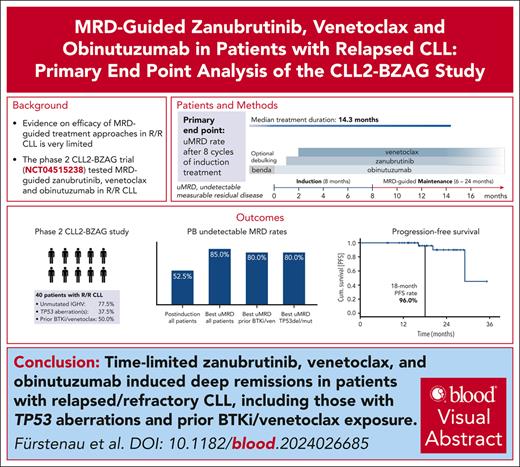

An MRD-guided treatment with zanubrutinib, venetoclax, and obinutuzumab achieved deep remissions in most patients with relapsed CLL.

Apart from COVID-19–related adverse events, the triple combination was well tolerated.

Visual Abstract

The phase 2 CLL2-BZAG trial tested a measurable residual disease (MRD)–guided combination treatment of zanubrutinib, venetoclax, and obinutuzumab after an optional bendamustine debulking in patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). In total, 42 patients were enrolled and 2 patients with ≤2 induction cycles were excluded from the analysis population per protocol. Patients had a median of 1 prior therapy (range, 1-5); 18 patients (45%) had already received a Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor (BTKi); 7 patients (17.5%) venetoclax; and, of these, 5 (12.5%) had received both. Fifteen patients (37.5%) had a TP53 mutation/deletion, and 31 (77.5%) had unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region gene. With a median observation time of 21.5 months (range, 8.0-35.3) the most common adverse events were COVID-19 (n = 26 patients), diarrhea (n = 15), infusion-related reactions (n = 15), thrombocytopenia (n = 14), nausea (n = 12), fatigue (n = 12), and neutropenia (n = 12). Two patients had fatal adverse events (COVID-19, and fungal pneumonia secondary to COVID-19). After 6 months of the triple combination, all patients responded, and 21 (52.5%; 95% confidence interval, 36.1-68.5) showed undetectable MRD (uMRD) in the peripheral blood. In many patients, remissions deepened over time, with a best uMRD rate of 85%. The estimated progression-free and overall survival rates at 18 months were 96% and 96.8%, respectively. No patient has yet required a subsequent treatment. In summary, the MRD-guided triple combination of zanubrutinib, venetoclax, and obinutuzumab induced deep remissions in a relapsed CLL population enriched for patients previously treated with a BTKi/venetoclax. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT04515238.

Medscape Continuing Medical Education online

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Medscape, LLC and the American Society of Hematology. Medscape, LLC is jointly accredited with commendation by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Successful completion of this CME activity, which includes participation in the evaluation component, enables the participant to earn up to 1.0 MOC points in the American Board of Internal Medicine's (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program. Participants will earn MOC points equivalent to the amount of CME credits claimed for the activity. It is the CME activity provider's responsibility to submit participant completion information to ACCME for the purpose of granting ABIM MOC credit.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test with a 75% minimum passing score and complete the evaluation at https://www.medscape.org/journal/blood; and (4) view/print certificate. For CME questions, see page 1334.

Disclosures

CME questions author Laurie Barclay, freelance writer and reviewer, Medscape, LLC, declares no competing financial interests.

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this activity, participants will:

Describe the efficacy of a minimal residual disease (MRD)–guided triple combination of venetoclax, zanubrutinib, and obinutuzumab, based on the primary end point analysis of the phase 2 CLL2-BZAG trial in 42 patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

Determine the safety and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis findings of an MRD-guided triple combination of venetoclax, zanubrutinib, and obinutuzumab, based on the primary end point analysis of the phase 2 CLL2-BZAG trial in 42 patients with R/R CLL

Identify clinical implications of the efficacy and safety of an MRD-guided triple combination of venetoclax, zanubrutinib, and obinutuzumab, based on the primary end point analysis of the phase 2 CLL2-BZAG trial in 42 patients with R/R CLL

Release date: March 20, 2025; Expiration date: March 20, 2026

Introduction

The treatment landscape for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has transformed significantly with the introduction of Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors (BTKi) and B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL2) inhibitors, leading to marked improvements in patient outcomes across different risk groups.1-15 Triple combinations involving BTKi, BCL2 inhibitors, and anti-CD20 antibodies have shown promising results in various settings.6,16-19 Recently, the GAIA/CLL13 trial has demonstrated high undetectable measurable residual disease (uMRD) rates and long progression-free survival (PFS) in patients treated with the first-line combination of venetoclax, ibrutinib, and obinutuzumab.20 Results from several phase 2 trials testing different triple combinations support these findings, with excellent outcomes in the first-line setting.16-18,21 However, evidence in the relapsed/refractory setting, especially in patients previously exposed to BTKi and/or venetoclax, remains limited, with only 3 published phase 2 studies testing triple combinations in this context. In 1 of these 3 studies venetoclax, ibrutinib, and obinutuzumab showed an encouraging uMRD rate of 50% in both the bone marrow and peripheral blood (PB) among 22 assessed patients at the end of treatment.18 In the second published phase 2 study, a best uMRD rate of 93.3% in the PB and a 3-year PFS rate of 85% were achieved with an MRD-guided combination of acalabrutinib, venetoclax, and obinutuzumab.22 In the third study, time-limited venetoclax, ublituximab, and umbralisib led to a PB uMRD rate of 67% in 42 assessed patients (46 enrolled patients) and a 3-year PFS rate of 74%.23

Given the shift toward time-limited combinations in the first-line treatment of patients with CLL, there is a high need for time-limited second- or later-line therapies that promise efficacy even in a post-BTKi/post-BCL2 inhibitor setting. With the implementation of an MRD-guided treatment discontinuation approach in this study, we aimed to keep the treatment exposure as low as possible while ensuring an adequate treatment duration for those patients with a slower response dynamic. Here, we report the primary end point analysis of the phase 2 CLL2-BZAG trial, testing an MRD-guided triple combination of venetoclax, zanubrutinib, and obinutuzumab after an optional debulking with bendamustine in patients with relapsed/refractory CLL.

Methods

Study design and patients

The CLL2-BZAG trial is an ongoing, phase 2, investigator-initiated study. Enrollment was completed in September 2022. Key eligibility criteria were age ≥18 years and previously treated, active CLL requiring treatment per International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (iwCLL) criteria. Patients with disease progression during a prior treatment with a BTKi and/or venetoclax and patients with potentially resistance-conferring BTK and/or BCL2 mutations were not eligible for participation. The complete list of inclusion/exclusion criteria can be found in supplemental Table 1 (supplemental Data, available on the Blood website).

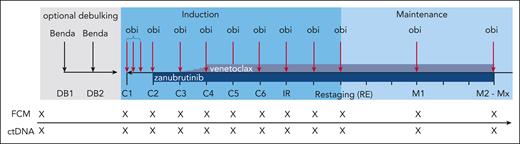

An optional debulking with 2 cycles of bendamustine (70 mg/m2 IV on days 1 and 2 repeated after 28 days) was recommended in patients with an increased risk for tumor lysis syndromes defined as an absolute lymphocyte count of ≥25 000/μL and/or any lymph nodes with a diameter of ≥5 cm. In case of contraindications (refractoriness to, or hypersensitivity against, bendamustine), debulking treatment was not recommended by the German CLL Study Group study office. Obinutuzumab, zanubrutinib, and venetoclax were sequentially initiated over the first 3 cycles of induction (Figure 1). IV obinutuzumab was administered in a dose of 1000 mg on days 1/2 (either as a split dose of 100/900 mg on days 1 and 2, or a full dose of 1000 mg on day 1), 8, and 15 of the first cycle, and on day 1 of the following cycles until the final restaging. Zanubrutinib (160 mg orally, twice daily) was added in the second induction cycle and continued until the end of study treatment. In the third induction cycle, venetoclax (400 mg orally) was added following the established 5-week ramp-up schedule. In total, induction treatment consisted of 8 cycles (ie, 6 cycles of the triple combination) before patients reached the final restaging. Induction cycles had 28 days, and maintenance cycles had 84 days. After the final restaging, maintenance treatment with obinutuzumab (1000 mg every 3 months), zanubrutinib (160 mg twice daily), and venetoclax (400 mg daily) was started. Maintenance treatment was continued until a complete response (CR) or clinical CR (ie, CR not confirmed by imaging and bone marrow aspiration) as well as uMRD in the PB was achieved in 2 consecutive measurements or for up to a total of 24 months. This results in a shortest possible regular treatment duration of ∼13 months (14 cycles a 28 days) and a maximal regular treatment duration of ∼31 months (34 cycles a 28 days). Diagnosis of CLL was centrally confirmed by immunophenotyping at the central laboratory in Cologne, Germany. In addition, karyotyping, fluorescence in situ hybridization, and mutational analysis of the immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region gene and of TP53 were performed centrally at baseline. Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scans were mandatory at screening and for confirmation of a CR. MRD was analyzed at the central laboratory in Kiel, Germany by multicolor flow cytometry following an established protocol, uMRD was defined as the detection of <1 CLL cell in 10 000 normal leukocytes (<10−4).24 Digital droplet polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR)-based analyses of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) included a panel of CLL-related mutations; known resistance mutations in BCL2, BTK, and PLCG2; and the patient-individual CLL-specific variable diversity joining rearrangement.25 The plasma used for ctDNA analyses was collected in PAXgene circulating cell-free DNA tubes (PreAnalytiX, Hombrechtikon, Switzerland). MRD and ctDNA analyses were performed monthly in the induction phase and 3-monthly during maintenance treatment. Responses were assessed by the investigators according to the iwCLL 2018 guidelines.26 Bone marrow evaluation was mandatory to establish a CR/CR with incomplete marrow recovery (CRi).

Treatment and sampling schedule. Every “X” on the sampling schedule represents an FCM and ctDNA sample. Benda, bendamustine; C1, cycle 1; C2, cycle 2; C3, cycle 3; C4, cycle 4; C5, cycle 5; C6, cycle 6; DB1, debulking cycle 1; DB2, debulking cycle 2; FCM, flow cytometry; IR, initial response assessment; M1, maintenance staging 1; M2, maintenance staging 2; Mx, maintenance stagings 3 to 8; obi, obinutuzumab; RE, final restaging.

Treatment and sampling schedule. Every “X” on the sampling schedule represents an FCM and ctDNA sample. Benda, bendamustine; C1, cycle 1; C2, cycle 2; C3, cycle 3; C4, cycle 4; C5, cycle 5; C6, cycle 6; DB1, debulking cycle 1; DB2, debulking cycle 2; FCM, flow cytometry; IR, initial response assessment; M1, maintenance staging 1; M2, maintenance staging 2; Mx, maintenance stagings 3 to 8; obi, obinutuzumab; RE, final restaging.

Continuous monitoring of adverse events was performed at each visit and adverse events were graded according to the National Cancer Institute common terminology criteria for adverse events, version 4.0.

Written informed consent was provided before enrolment and the trial protocol was approved by the responsible health authorities and institutional review boards. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization good clinical practice guideline.

Statistical analysis

The primary end point of the study was the rate of patients with uMRD in the PB after 6 cycles of the full triple combination and was assessed at the final restaging after 8 28-day cycles of induction treatment. Secondary end points reported here were the overall response rate (defined as the rate of CR, CRi, or partial response), CR rate (defined as the rate of CR or CRi) after debulking, induction and maintenance and rates of patients with uMRD at different time points, PFS (defined as the time from registration to first disease progression or death from any cause), overall survival (OS; defined as the time from registration to death), and safety. The best uMRD rate was defined as all patients in whom uMRD was achieved at any time point in the study. Predefined exploratory subgroup analyses of primary and secondary end points were performed.

All patients who received at least 2 complete cycles of induction treatment (full analysis set) were included in the efficacy analysis. Further exploratory post-hoc analyses on efficacy were performed on the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, which contained all registered patients. The safety population comprised all patients who received at least 1 dose of study drug.

The primary end point (uMRD rate at the final restaging) was analyzed descriptively without any formal confirmatory testing, the 95% confidence interval was calculated according to the Clopper-Pearson method. For time-to-event analyses, the Kaplan-Meier estimates were used; response rates, MRD rates, and other characteristics were described in counts and percentages.

The data cutoff of this primary end point analysis was 5 June 2023.

Statistical analyses were done using SPSS (version 28.0.1.0). The CLL2-BZAG study was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT04515238.

Results

Baseline characteristics

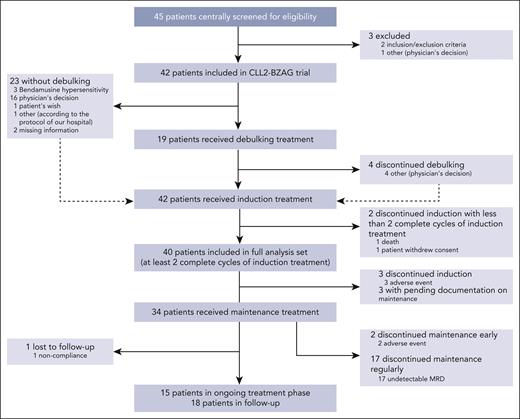

Between November 2020 and September 2022, 45 patients were screened for eligibility and 42 patients were included in the CLL2-BZAG trial. Two patients were excluded from the full analysis set (n = 40) because they had received <2 complete cycles of induction treatment (Figure 2).

Patient flow diagram according to CONSORT guidelines. CONSORT, consolidated standards of reporting trials.

Patient flow diagram according to CONSORT guidelines. CONSORT, consolidated standards of reporting trials.

Patients had a median age of 64 years (interquartile range, 57-70) and 27 of 40 patients (67.5%) were male (Table 1). The median cumulative illness rating scale score was 3 (interquartile range, 2.0-5.8) and the median creatinine clearance was 82.1 mL/min (interquartile range, 58.4-100.5 mL/min). The median number of previous treatments was 1 (range, 1-5), 18 patients (45%) had already received a BTKi in a prior line of treatment, 7 (17.5%) venetoclax, and 5 (12.5%) of these patients had received both. In total, 20 patients (50%) had received a BTKi and/or venetoclax (supplemental Table 2B, supplemental Data). Of these, 18 patients received venetoclax and/or BTKi in the context of time-limited treatment regimens, with 17 completing treatment as planned (1 toxicity-related early discontinuation; supplemental Table 2C, supplemental Data). Two of these patients also had a continuous monotherapy with a BTKi as a prior line of treatment (both discontinued because of intolerance). Two patients received BTKi monotherapy but no further time-limited regimens with venetoclax and/or BTKi, both discontinued early because of intolerance. Fifteen patients (37.5%) had 17p deletions and/or TP53 mutations, 31 (77.5%) had an unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region gene status, and 19 of 38 patients (50%) with available information had a complex karyotype defined as ≥3 cytogenetic aberrations.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristics . | Full analysis set . |

|---|---|

| All patients of the full analysis set, N | 40 |

| Sex, N (%) | 40 |

| Female, n (%) | 13 (32.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 27 (67.5) |

| Age, y | 40 |

| Median (range) | 64 (40-82) |

| Time since first diagnosis, mo | 40 |

| Median (range) | 103.5 (42.2-240.2) |

| Binet stage, N (%) | 40 |

| A, n (%) | 11 (27.5) |

| B, n (%) | 19 (47.5) |

| C, n (%) | 10 (25.0) |

| Total CIRS score | 40 |

| Median (range) | 3 (0-12) |

| Creatinine clearance (mL/min) | 40 |

| Median (range) | 82.1 (35.6-153.1) |

| del(17p), N (%) | 40 |

| Yes, n (%) | 5 (12.5) |

| del(11q), N (%) | 40 |

| Yes, n (%) | 15 (37.5) |

| Trisomy 12, N (%) | 40 |

| Yes, n (%) | 3 (7.5) |

| del(13q), N (%) | 40 |

| Yes, n (%) | 23 (57.5) |

| Type according to hierarchical model, N (%) | 40 |

| del(17p), n (%) | 5 (12.5) |

| del(11q), n (%) | 15 (37.5) |

| Trisomy 12, n (%) | 1 (2.5) |

| Not del(17p)/del(11q)/trisomy 12/del(13q), n (%) | 9 (22.5) |

| del(13q) alone, n (%) | 10 (25.0) |

| IGHV mutational status, N (%) | 40 |

| Unmutated, n (%) | 31 (77.5) |

| Mutated, n (%) | 9 (22.5) |

| TP53 mutational status, N (%) | 40 |

| Unmutated, n (%) | 26 (65.0) |

| Mutated, n (%) | 14 (35.0) |

| TP53 status, N (%) | 40 |

| None, n (%) | 25 (62.5) |

| Deleted and/or mutated, n (%) | 15 (37.5) |

| NOTCH1 mutational status, N (%) | 40 |

| Unmutated, n (%) | 30 (75.0) |

| Mutated, n (%) | 10 (25.0) |

| SF3B1 mutational status, N (%) | 40 |

| Unmutated, n (%) | 27 (67.5) |

| Mutated, n (%) | 13 (32.5) |

| Serum β2-microglobulin (mg/dL) | 39 |

| Median (range) | 4.5 (2.1-17.2) |

| Complex karyotype, N (%) | 38 |

| Noncomplex karyotype (<3 aberrations), n (%) | 19 (50.0) |

| Complex karyotype (≥3 aberrations), n (%) | 19 (50.0) |

| CLL-IPI risk group, N (%) | 39 |

| Low, n (%) | 2 (5.1) |

| Intermediate, n (%) | 6 (15.4) |

| High, n (%) | 18 (46.2) |

| Very high, n (%) | 13 (33.3) |

| Previous lines of treatment | 40 |

| Median (range) | 1 (1-5) |

| Previous treatment with venetoclax, N (%) | 40 |

| Yes, n (%) | 7 (17.5) |

| Previous treatment with a BTKi, N (%) | 40 |

| Yes, n (%) | 18 (45.0) |

| Previous treatment with a BTKi and venetoclax, N (%) | 40 |

| Yes, n (%) | 5 (12.5) |

| Previous treatment with a BTKi and/or venetoclax, N (%) | 40 |

| Yes, n (%) | 20 (50.0) |

| Characteristics . | Full analysis set . |

|---|---|

| All patients of the full analysis set, N | 40 |

| Sex, N (%) | 40 |

| Female, n (%) | 13 (32.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 27 (67.5) |

| Age, y | 40 |

| Median (range) | 64 (40-82) |

| Time since first diagnosis, mo | 40 |

| Median (range) | 103.5 (42.2-240.2) |

| Binet stage, N (%) | 40 |

| A, n (%) | 11 (27.5) |

| B, n (%) | 19 (47.5) |

| C, n (%) | 10 (25.0) |

| Total CIRS score | 40 |

| Median (range) | 3 (0-12) |

| Creatinine clearance (mL/min) | 40 |

| Median (range) | 82.1 (35.6-153.1) |

| del(17p), N (%) | 40 |

| Yes, n (%) | 5 (12.5) |

| del(11q), N (%) | 40 |

| Yes, n (%) | 15 (37.5) |

| Trisomy 12, N (%) | 40 |

| Yes, n (%) | 3 (7.5) |

| del(13q), N (%) | 40 |

| Yes, n (%) | 23 (57.5) |

| Type according to hierarchical model, N (%) | 40 |

| del(17p), n (%) | 5 (12.5) |

| del(11q), n (%) | 15 (37.5) |

| Trisomy 12, n (%) | 1 (2.5) |

| Not del(17p)/del(11q)/trisomy 12/del(13q), n (%) | 9 (22.5) |

| del(13q) alone, n (%) | 10 (25.0) |

| IGHV mutational status, N (%) | 40 |

| Unmutated, n (%) | 31 (77.5) |

| Mutated, n (%) | 9 (22.5) |

| TP53 mutational status, N (%) | 40 |

| Unmutated, n (%) | 26 (65.0) |

| Mutated, n (%) | 14 (35.0) |

| TP53 status, N (%) | 40 |

| None, n (%) | 25 (62.5) |

| Deleted and/or mutated, n (%) | 15 (37.5) |

| NOTCH1 mutational status, N (%) | 40 |

| Unmutated, n (%) | 30 (75.0) |

| Mutated, n (%) | 10 (25.0) |

| SF3B1 mutational status, N (%) | 40 |

| Unmutated, n (%) | 27 (67.5) |

| Mutated, n (%) | 13 (32.5) |

| Serum β2-microglobulin (mg/dL) | 39 |

| Median (range) | 4.5 (2.1-17.2) |

| Complex karyotype, N (%) | 38 |

| Noncomplex karyotype (<3 aberrations), n (%) | 19 (50.0) |

| Complex karyotype (≥3 aberrations), n (%) | 19 (50.0) |

| CLL-IPI risk group, N (%) | 39 |

| Low, n (%) | 2 (5.1) |

| Intermediate, n (%) | 6 (15.4) |

| High, n (%) | 18 (46.2) |

| Very high, n (%) | 13 (33.3) |

| Previous lines of treatment | 40 |

| Median (range) | 1 (1-5) |

| Previous treatment with venetoclax, N (%) | 40 |

| Yes, n (%) | 7 (17.5) |

| Previous treatment with a BTKi, N (%) | 40 |

| Yes, n (%) | 18 (45.0) |

| Previous treatment with a BTKi and venetoclax, N (%) | 40 |

| Yes, n (%) | 5 (12.5) |

| Previous treatment with a BTKi and/or venetoclax, N (%) | 40 |

| Yes, n (%) | 20 (50.0) |

CIRS, cumulative illness rating scale; IGHV, immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region gene; IPI, International Prognostic Index.

Treatment exposure

Overall, 19 patients (47.5%) received bendamustine debulking; of these, 15 patients completed the planned 2 cycles, and 4 patients received only 1 cycle of bendamustine. In total, 3 patients (7.5%) discontinued induction treatment early, all because of adverse events (COVID-19, n = 2; hepatic enzyme increase, n = 1). During induction, 14 patients (35%) experienced at least 1 venetoclax dose modification because of an adverse event, and, in 10 patients (25%), zanubrutinib dose was modified after an adverse event (supplemental Table 3, supplemental Data). At the time point of the data cutoff, 34 patients had started with the maintenance phase (documentation pending in 3 patients). Two patients (5.9%) discontinued maintenance treatment earlier than foreseen by the study protocol, both because of adverse events (squamous cell carcinoma of the hypopharynx, n = 1; and chronic kidney disease, n = 1) in cycle 4 and cycle 2 of maintenance, respectively. Seventeen patients (50%) have finished study treatment according to protocol (uMRD in 2 consecutive measurements), and in 15 patients (44.1%) maintenance treatment is ongoing. The current median treatment duration across all 40 patients is 14.3 months (interquartile range, 11.2-16.7), with a relevant proportion of patients still on treatment. The median treatment duration of patients who have finished treatment (n = 22) was 14.9 months (interquartile range, 12.9-17.5).

Efficacy

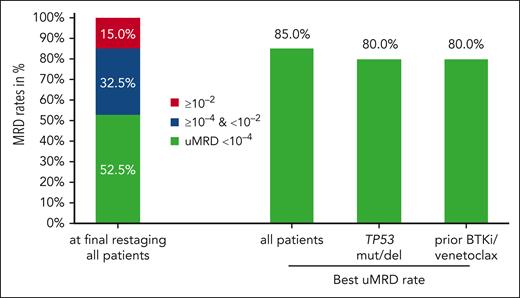

With a median observation time of 21.5 months (interquartile range, 16.5-25.9), all patients have reached the final restaging after 6 cycles of the triple combination. At the final restaging, all 40 patients responded, 3 patients (7.5%) with a CR or CRi, and 37 (92.5%) with a partial response (supplemental Table 4, supplemental Data). uMRD in the PB measured at the final restaging was achieved in 21 of 40 patients (52.5%; 95% confidence interval, 36.1-68.5; Figure 3). uMRD at final restaging was achieved in 8 of 20 patients (40%) previously exposed to BTKis and/or venetoclax and in 8 of 15 patients (53.3%) with TP53 aberrations (supplemental Table 5, supplemental Data). Remissions deepened over the course of treatment, while at the final restaging, 19 of 40 patients (47.5%) still had detectable MRD, this fraction went down to 8 of 34 patients (23.5%) after maintenance cycle 1, and 4 of 32 (12.5%) after maintenance cycle 2 (supplemental Table 6, supplemental Data). The best uMRD rate, that is, the rate of patients in whom uMRD was achieved at any time point in the study, was 85% (34 of 40 patients) in the whole study population, 80% (16 of 20) in patients previously exposed to BTKis and/or venetoclax, and 80% (12 of 15) in patients with TP53 aberrations (Figure 3). The uMRD rates at final restaging and the best uMRD rates were similar in patients who had received a debulking with bendamustine (52.6% and 89.5%) and patients who had not (52.4% and 81%). The uMRD rates based on the ITT population can be found in the supplemental Data (supplemental Tables 7 and 8).

MRD rates in the PB are shown for all patients at final restaging. In addition, best uMRD rates in the PB for all patients, for patients with TP53 aberrations, and for patients with prior exposure to BTKis and/or venetoclax are shown. RE, final restaging.

MRD rates in the PB are shown for all patients at final restaging. In addition, best uMRD rates in the PB for all patients, for patients with TP53 aberrations, and for patients with prior exposure to BTKis and/or venetoclax are shown. RE, final restaging.

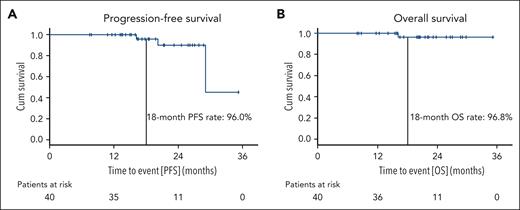

Median PFS was 29.1 months, the estimated 18-month PFS rate was 96% (Figure 4). Estimated PFS rates at 18 months were similar for patients with prior BTKi and/or venetoclax treatment (90%) and for patients with TP53 aberrations (100%), as well as for patients who had received a debulking with bendamustine (92.9%) and those who had not (100%). In total, 2 patients had disease progressions according to iwCLL criteria. One disease progression occurred 9 months after maintenance treatment was stopped because of confirmed uMRD. In the other patient, treatment was stopped after 6 induction cycles because of recurring infections and disease progression occurred 12 months after the early treatment discontinuation. Both patients with clinical disease progressions have so far not required a subsequent CLL treatment.

Progression-free and overall survival. PFS (A) and OS (B) are shown for the full analysis set; patients at risk at the respective time points are listed below the graphs.

Progression-free and overall survival. PFS (A) and OS (B) are shown for the full analysis set; patients at risk at the respective time points are listed below the graphs.

Median OS was not reached, the estimated 18-month OS rate was 96.8%. One patient died 11 months after the early discontinuation of induction treatment because of a fungal pneumonia secondary to a long-lasting severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. A second fatal case of COVID-19 was reported in a patient who was excluded from the full analysis set because of <2 cycles of induction treatment. PFS and OS data based on the ITT population are shown in the supplemental Data (supplemental Figures 1 and 2).

Safety

Until the data cutoff (5 June 2023), 445 adverse events were reported in the safety population (n = 42 patients), of these, 39 (8.8%) were reported in 19 patients during debulking treatment, 303 (68.1%) in 42 patients during induction treatment, 84 (18.9%) in 34 patients during maintenance, and 19 (4.3%) in the follow-up. In total, 80 (18%) adverse events led to an adjustment of at least 1 study drug, with dose reductions in 22 cases, interruptions in 65 cases, and permanent discontinuations in 7 cases. The most common adverse events were COVID-19 (n = 26 patients), diarrhea (n = 15), infusion-related reactions (n = 15), thrombocytopenia (n = 14), nausea (n = 12), fatigue (n = 12), and neutropenia (n = 12; Table 2). The most frequent grade ≥3 adverse events were neutropenia (n = 10 patients), COVID-19 (n = 9), thrombocytopenia (n = 7), and pneumonia (n = 5). Two patients had grade ≥3 cardiac adverse events, 1 patient with a grade 3 non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction, and 1 patient with 2 episodes of grade 3 atrial fibrillation and a history of atrial fibrillation.

Adverse events that occurred in 10% or more of patients (any CTC grade) and/or were of CTC grade 3 or higher

| Adverse event . | Any CTC grade . | CTC grade ≥3 . |

|---|---|---|

| All patients of the safety population, N (%) | 40 | 40 |

| Anemia, n (%) | 3 (7.1) | 3 (7.1) |

| Arthralgia, n (%) | 6 (14.3) | 0 |

| Back pain, n (%) | 5 (11.9) | 0 |

| Constipation, n (%) | 9 (21.4) | 1 (2.4) |

| COVID-19, n (%) | 26 (61.9) | 9 (21.4) |

| Diarrhea, n (%) | 15 (35.7) | 1 (2.4) |

| Dizziness, n (%) | 9 (21.4) | 0 |

| Fatigue, n (%) | 12 (28.6) | 0 |

| Headache, n (%) | 7 (16.7) | 0 |

| Hematoma, n (%) | 8 (19.0) | 1 (2.4) |

| Hyperuricemia, n (%) | 4 (10.0) | 1 (2.4) |

| Infusion-related reaction, n (%) | 15 (35.7) | 1 (2.4) |

| Leukopenia,∗ n (%) | 5 (11.9) | 4 (9.5) |

| Nausea, n (%) | 12 (28.6) | 0 |

| Neutropenia,† n (%) | 12 (28.6) | 10 (23.8) |

| Pneumonia,‡ n (%) | 7 (16.7) | 5 (11.9) |

| Pyrexia, n (%) | 5 (11.9) | 0 |

| Rash, n (%) | 7 (16.7) | 0 |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.4) |

| Thrombocytopenia,§ n (%) | 14 (33.3) | 7 (16.7) |

| Tumor lysis syndrome, n (%) | 3 (7.1) | 3 (7.1) |

| Vomiting, n (%) | 5 (11.9) | 0 |

| Adverse event . | Any CTC grade . | CTC grade ≥3 . |

|---|---|---|

| All patients of the safety population, N (%) | 40 | 40 |

| Anemia, n (%) | 3 (7.1) | 3 (7.1) |

| Arthralgia, n (%) | 6 (14.3) | 0 |

| Back pain, n (%) | 5 (11.9) | 0 |

| Constipation, n (%) | 9 (21.4) | 1 (2.4) |

| COVID-19, n (%) | 26 (61.9) | 9 (21.4) |

| Diarrhea, n (%) | 15 (35.7) | 1 (2.4) |

| Dizziness, n (%) | 9 (21.4) | 0 |

| Fatigue, n (%) | 12 (28.6) | 0 |

| Headache, n (%) | 7 (16.7) | 0 |

| Hematoma, n (%) | 8 (19.0) | 1 (2.4) |

| Hyperuricemia, n (%) | 4 (10.0) | 1 (2.4) |

| Infusion-related reaction, n (%) | 15 (35.7) | 1 (2.4) |

| Leukopenia,∗ n (%) | 5 (11.9) | 4 (9.5) |

| Nausea, n (%) | 12 (28.6) | 0 |

| Neutropenia,† n (%) | 12 (28.6) | 10 (23.8) |

| Pneumonia,‡ n (%) | 7 (16.7) | 5 (11.9) |

| Pyrexia, n (%) | 5 (11.9) | 0 |

| Rash, n (%) | 7 (16.7) | 0 |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.4) |

| Thrombocytopenia,§ n (%) | 14 (33.3) | 7 (16.7) |

| Tumor lysis syndrome, n (%) | 3 (7.1) | 3 (7.1) |

| Vomiting, n (%) | 5 (11.9) | 0 |

Including preferred terms “leukopenia” and “white blood cell count decreased.”

Including preferred terms “neutropenia” and “neutrophil count decreased.”

Including preferred terms “pneumonia,” “pneumonia pseudomonal,” and “pneumonia fungal.”

Including preferred terms “thrombocytopenia” and “platelet count decreased.”

ctDNA analyses

In an exploratory analysis conventional multicolor flow cytometry–based MRD monitoring was compared with plasma-based ddPCR assays tracking patient-specific variable diversity joining rearrangements. In total, 281 paired flow cytometry and ddPCR samples were analyzed throughout the course of the study. Concordant results (ie, uMRD/ctDNA negative or MRD/ctDNA positive) were observed in 245 of 281 (87.2%) samples whereas 36 (12.8%) showed discordant results. In 23 of 36 (63.9%) discordant samples, patient-specific ctDNA was still detected in plasma when conventional flow cytometry indicated uMRD; in 13 (36.1%) samples, MRD was detected whereas no patient-specific ctDNA was found. Apart from 1 PLCG2_S707F mutation that occurred 11 months after the end of treatment in a patient who was not preexposed to a BTKi, no acquisition of known resistance mutations, in particular in BTK and BCL2, was observed using ddPCR.

Discussion

In this primary end point analysis of the phase 2 CLL2-BZAG trial the time-limited, MRD-guided triple combination of venetoclax, zanubrutinib, and obinutuzumab led to an uMRD rate in the PB of 52.5% at the end of induction treatment in patients with relapsed CLL. uMRD increased with ongoing therapy, resulting in a best uMRD rate of 85%, with 15 patients still on maintenance treatment. Moreover, the combination showed high 18-month PFS (96%) and 18-month OS (96.8%) rates. Best uMRD rates and survival rates were similar for patients previously exposed to BTKi and/or venetoclax and patients with TP53 aberrations. No unexpected toxicities occurred with the triple combination and the reported events reflect the described safety profiles of the 4 drugs used in this trial. ctDNA-based and flow cytometry–based MRD assessments were highly concordant, and the combination of both methods appears to enhance the detection of residual disease.

In the management of relapsed/refractory CLL, a considerable heterogeneity exists defined by disease biology, progression dynamics, prior treatment, and exposure to specific therapeutic agents. Within this diverse patient collective, uniform treatment modalities such as continuous monotherapies or fixed-duration combinations pose the risk of either overtreatment or undertreatment. Overtreatment could imply an unnecessary burden of medication intake, physician visits, and possibly even toxicities; whereas undertreatment, leaving substantial residual disease upon treatment completion, carries the risk of early need of a next line of treatment. Both may facilitate the emergence of resistance mutations. The patient cohort enrolled in this trial embodies this clinical diversity in the relapsed/refractory setting with a broad range of prior treatment lines, including 50% of patients with prior exposure to BTKis and/or venetoclax and a high variability in the genetic risk profile. This heterogeneity is reflected in the different time points of conversion to uMRD in this population with approximately half of the patients already showing uMRD after 6 induction cycles whereas large proportion of patients appears to need at least 6 more months of maintenance to convert to uMRD. Although the follow-up in this study is still too limited to draw conclusions on the median treatment duration, we recently published a similar study using acalabrutinib, venetoclax, and obinutuzumab in which the median treatment duration was 14.7 months. This is considerably shorter than the 2 most widely used approved options in the relapsed/refractory setting, venetoclax-rituximab (2 years) and BTKi monotherapy (until progression). Already at this early analysis time point, uMRD was achieved in 85% of all patients in the CLL2-BZAG trial and it can be anticipated that this number will increase with ongoing maintenance treatment.

The uMRD rates observed in this trial compare well with the standard time-limited relapsed/refractory treatment option, venetoclax-rituximab (PB uMRD in MURANO: 62% after 6 months), although the MURANO study did not include venetoclax-pretreated patients and very few patients who had received BTKis in a prior line.2,27,28 Compared with other triple combinations in the relapsed/refractory setting such as venetoclax-ibrutinib-obinutuzumab (uMRD rate in the PB and bone marrow after 16 months: 50%) or venetoclax-acalabrutinib-obinutuzumab (PB uMRD after 6 months of the full triplet: 76%), the uMRD rate appears generally comparable.18,19,22 However, the time point to assess the primary end point might have been too early to fully capture the efficacy in this high-risk collective. With a best uMRD rate of 85% and a substantial proportion of patients still receiving maintenance treatment further deepening of responses and more conversions to uMRD with continued maintenance are expected, which might eventually translate into prolonged PFS. With regard to the interpretation of PFS data, it is still too early to draw definitive conclusions, but the 18-month PFS and OS results also compare well with other standard regimens in the relapsed/refractory setting such as the MURANO regimen (2-year PFS: 84.9%), zanubrutinib monotherapy (2-year PFS: 78.4%), or acalabrutinib monotherapy (1-year PFS: 88%).9,12,29,30 In the first-line setting, the BOVen regimen, combining the same 3 drugs as the CLL2-BZAG study, venetoclax-zanubrutinib-obinutuzumab with a MRD-guided strategy, has achieved a best uMRD rate of 94% and durable responses,17 underscoring both the efficacy of this triple regimen and the inherent differences in the treatment of a relapsed/refractory and a treatment-naïve collective. Although the early efficacy data of this regimen looks promising and compares well with continuous BTKi monotherapy in this setting, it is important to acknowledge that this study cohort consists of rather young and fit patients with CLL mostly treated at large academic centers. It remains to be seen whether triple combinations such as zanubrutinib, venetoclax, and obinutuzumab can be as easily administered as currently established options in an older and frailer patient population.

The CR rate at the final restaging after 8 cycles of induction treatment was comparatively low (7.5%). In our opinion, this is not a reflection of low efficacy but rather because of the strict response criteria and the time points of response assessments. As both a computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scan and a bone marrow analysis were mandatory to define a CR/CRi and both were only recommended when a clinical CR and uMRD in the PB were achieved, most patients have not yet received the necessary examinations to confirm a CR. Based on observations from the CLL2-BAAG trial that had the same study design and rules for response assessment, we expect the CR rate to rise with additional follow-up.19

No unexpected toxicities were observed in this study, so far. Hematological toxicities were anticipated and occurred in most patients; however, no patients experienced febrile neutropenia. Infections were generally of lower common toxicity criteria (CTC) grades and 15 patients (35.7%) had CTC grade 3 to 5 infections. Although in this patient population, COVID-19–associated deaths were expected because of the recruitment of patients from November 2020 to September 2022, the 2 fatal COVID-19 cases in this study (1of them due to fungal pneumonia following long-lasting COVID-19) should prompt meticulous reporting of infectious adverse events in studies using triple combinations of a BCL2 inhibitor, a BTKi, and a CD20 antibody.31-35

Based on previous trials and an assumed positive effect on tumor lysis syndrome risk and the incidence of infusion-related reactions, an optional debulking with bendamustine was included in the protocol.19,36-38 Only 19 (47.5%) of the patients received the optional bendamustine debulking. Debulking with bendamustine was not associated with better efficacy outcomes in this trial. Considering the now widely established BTKi-based debulking schedules before the start of concomitant venetoclax and the general movement toward entirely chemotherapy-free regimens, it is unlikely that this debulking approach will be further evaluated. Given the good data on BTKi-based tumor lysis risk reduction before the initiation of venetoclax combinations, this combination of zanubrutinib, venetoclax, and obinutuzumab might even be administered in a more tolerable way if induction treatment was started with a 3-month zanubrutinib lead-in instead of obinutuzumab.39

This analysis has several important limitations: the primary end point analysis was scheduled rather early, resulting in substantially lower uMRD rates compared with the following time points 3 and 6 months later. Moreover, following the prespecified definition of the analysis population, 2 patients with very early treatment discontinuations (ie, <2 complete induction cycles) were excluded from the efficacy analysis. These 2 patients arguably had worse treatment outcomes and their exclusion potentially overestimates the efficacy of this study treatment. The interpretation of the efficacy and safety data is further limited by the fact that half of the patients received a debulking with bendamustine, resulting in 2 patient groups with slightly different treatments.

In summary, this MRD-guided combination of venetoclax, zanubrutinib, and obinutuzumab shows promising efficacy in a relapsed/refractory CLL population enriched for patients with high-risk genetics and patients previously exposed to venetoclax/BTKis. Given the potential of this MRD-driven, individualized treatment approach to achieve deep remissions in most patients even when preexposed to targeted treatments, this time-limited triple combination warrants further exploration in relapsed/refractory CLL.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all patients, physicians, and trial staff at the sites for their participation in the study. The authors also thank Berit Falkowski, Aline Zey, Laura Miesen, Anne Domonell, Daniela Hermert, and Sophie Reidel, who worked as project managers; Olga Korf, Viktoria Monar, Anne Wosnitza, Alwina Flock, and Irene Preißler-Stodden, who worked as data managers; Tanja Annolleck, Christina Rhein, Katharina Löhers, and Sabine Frohs, who worked as safety managers in the CLL2-BZAG trial; and the monitors from the “Competence Network Malignant Lymphoma” (“Kompetenznetz Maligne Lymphome”). The droplet digital polymerase chain reaction analyses were supported by the CLL-CLUE project in the European Research Area PerMed program.

M.H. is supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, SFB 1530, projects B01 and Z01. The trial was sponsored by the German CLL Study Group with financial support and study drug provision from BeiGene, Roche, and AbbVie.

Authorship

Contribution: M.F., M.H., and P.C. were responsible for the conception and design of the study; M.F., A.G., S.R., A.F., J.S., F.S., K.F., and P.C. were responsible for the trial management; M.F., C.S., E.T., M.R., J.B., H.H., B.S., A.L.I., U.G., A. Stoltefuß, B.H., R.E., J.S., O.A.-S., F.S., P.L., S.S., B.E., M.H., and P.C. were responsible for the recruitment and treatment of patients; M.F., A.G., S.R., and P.C. had access to the raw data; M.F. and P.C. did a central review of all clinical data; C.S., E.T., M.R., F.K., J.W., K.-A.K., A. Schilhabel, M.B., and S.S. performed the laboratory analyses; A.G. and S.R. performed the statistical analysis; M.F. and P.C. wrote the first draft of the manuscript; and all authors interpreted the data, and reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.F. reports research funding (to institution) from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Janssen, and Roche and honoraria from AbbVie. C.S. reports honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, and Janssen. E.T. reports travel support from AbbVie, Janssen, and BeiGene and honoraria for presentations and advisory board participation from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Janssen, and Roche. S.R. reports honoraria from MSD. M.R. reports payments/honoraria for lectures/presentations from Janssen, AstraZeneca, and Roche; reports consulting fees from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Roche; was supported for attending meetings/travel by AstraZeneca; and received grants/contracts from AbbVie and F. Hoffmann-La Roche. J.B. reports honoraria from AbbVie, Roche, Alexion, AstraZeneca, and Oncopeptides and travel grants from BeiGene. H.H. participated in advisory boards for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, and Janssen. A.L.I. participated in advisory boards for AbbVie, Janssen-Cilag, Roche, and Onkowissen; reports honoraria from Illumina, Roche, AstraZeneca, Ars Tempi, Takeda, Expanda, Sobi, and iOmedico; and reports travel grants or accommodation expenses from Roche, Janssen-Cilag, and Takeda. U.G. reports research funding (to institution) from AstraZeneca, Mirati Therapeutics, and Epizyme and honoraria from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Celltrion, Ipsen, and Takeda. R.E. participated in advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Cilag; reports honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Incyte, Oncopeptides, and Sanofi-Aventis; and reports research support from Octapharma. A.F. reports research funding from AstraZeneca (to institution); honoraria from AstraZeneca; and travel support from AbbVie. K.F. reports advisory board honoraria from AbbVie, Roche, and AstraZeneca; honoraria from Roche and AstraZeneca; and travel support from Roche. O.A.-S. received honoraria from Janssen-Cilag, Roche, Gilead Sciences, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Adaptive Biotechnologies, and BeiGene; reports a consulting or advisory role in Roche, Janssen-Cilag, Gilead Sciences, and AbbVie; received research funding from BeiGene, Roche, AbbVie, and Janssen/Pharmacyclics; and received travel and accommodation expenses from Roche, AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, and Janssen-Cilag. F.S. reports honoraria and research support from AstraZeneca and travel support from Lilly Pharmaceuticals. J.W. is an employee of Qiagen, Hilden, Germany. K.-A.K. reports consultancy, speaker bureau fees, and research support from Janssen, Roche, and AbbVie. M.B. reports personal fees from Incyte and AstraZeneca (advisory board), Jazz (travel support), Becton Dickinson and Pfizer (speakers bureau), Janssen (travel support and speakers bureau), grants and personal fees from Amgen (advisory board, speakers bureau, travel support, and research support [to institution]), all outside the submitted work. P.L. reports honoraria from AstraZeneca, BeiGene, AbbVie, and Janssen; has participated in advisory boards for AstraZeneca, BeiGene, AbbVie, and Janssen; and has received research funding from Janssen. S.S. received advisory board honoraria, research support, travel support, and speaker’s fees from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Janssen, Novartis, and Sunesis. B.E. was part of the speakers bureaus and participated in advisory boards for AbbVie, Janssen, and Roche. M.H. received institutional research support from AbbVie, Roche, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Gilead, and BeiGene. P.C. reports research funding from Acerta, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, F. Hoffmann-LaRoche, Gilead, Janssen-Cilag, and Novartis; honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Bristol Myers Squibb, F. Hoffmann-LaRoche, Janssen-Cilag, and Novo Nordisk; advisory board participation with Acerta, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Janssen-Cilag, and Novartis; and travel support from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, F. Hoffmann LaRoche, Gilead, Janssen-Cilag, and Novo Nordisk. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Moritz Fürstenau, German CLL Study Group, Gleueler Str 176-178, 50935 Köln, Germany; email: moritz.fuerstenau@uk-koeln.de.

References

Author notes

Presented at the 65th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Diego, CA, 9 to 12 December 2023.

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Moritz Fürstenau (moritz.fuerstenau@uk-koeln.de).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal