In this issue of Blood, Condoluci et al, on behalf of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK), report the primary end point analysis of the phase 2 SAKK 34/17 trial investigating a measurable residual disease (MRD)-guided combination treatment with ibrutinib and venetoclax (I+V) in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).1 In a population of typical patients with relapsed CLL (median age 69 years, all risk groups) who had not yet received a BTK inhibitor (BTKi) or BCL2 inhibitor (BCL2i), Condoluci et al were able to achieve deep remissions in the majority of patients with a longer than usual I+V treatment of at least 2.5 years. Although the efficacy outcomes compare well with other time-limited options in the relapse setting, premature treatment discontinuations and cardiac adverse events were more frequent than with shorter I+V regimens.

Despite the approval und widespread adoption of efficacious time-limited combination therapies in the first-line context (venetoclax-obinutuzumab, I+V, probably soon acalabrutinib-venetoclax), there is a lack of equally good options in the relapse setting where venetoclax-rituximab is the only approved time-limited therapy.2,3 With an increasing number of patients requiring second-line treatment following long treatment-free intervals after time-limited first-line therapies, a time-limited retreatment with a combination of BTKi and BCL2i (with or without obinutuzumab) would be an ideal option promising good efficacy and the prospect of another long treatment-free interval.

In this phase 2 study of 30 patients with relapsed CLL, Condoluci et al used a prolonged ibrutinib lead-in to reduce tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) risk and an extended I+V treatment (24 instead of the established 12 months) with the aim of increasing undetectable MRD rates compared with shorter BTKi plus BCL2i regimens.4,5 The key takeaways from the SAKK 34/17 include the following:

With a 6-month ibrutinib lead-in, the proportion of patients with high TLS risk was reduced from 53% at baseline to 14% before starting venetoclax.

At the end of combination treatment (after month 30), undetectable MRD (uMRD) in peripheral blood (PB) was achieved in 63% of patients and uMRD in both PB and bone marrow in 53%.

Estimated progression-free survival (PFS) after 30 months was 90%, comparing favorably with established options in the relapse setting.

More than a third of all patients (37%) had to discontinue treatment earlier than planned, mostly due to adverse events, a rate 2 to 3 times as high as with shorter I+V regimens.

Although the toxicity profile was generally comparable to shorter I+V combinations, longer ibrutinib exposure in SAKK 34/17 was accompanied by a higher rate of grade 3 to 4 cardiac adverse events (10%).

In a detailed comparison of different cell-based (flow cytometry, immunoglobulin high-throughput sequencing [Ig HTS]) and cell-free (CAPP-seq) methods of MRD measurement, Ig HTS clearly demonstrated the highest sensitivity in detecting MRD.

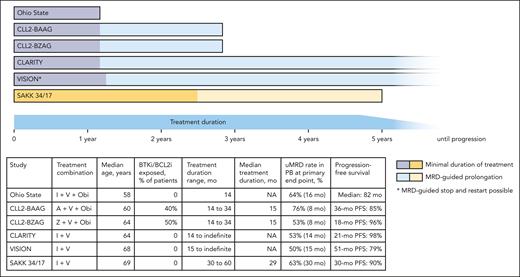

Undoubtedly these efficacy outcomes are excellent, but do they justify a substantially longer treatment? For an illustrative comparison of different treatment durations in relapsed/refractory CLL, the figure shows published studies using BTKi plus BCL2i (with or without obinutuzumab) combinations in this setting.6-10 Most studies in this space use a uMRD-triggered treatment discontinuation approach, allowing patients with deep remissions to stop treatment at a predefined time point, resulting in a minimal treatment duration of 14 to 15 months (CLL2-BZAG, CLL2-BAAG, CLARITY, VISION) to 30 months in the SAKK 34/17 study. With the caveat of different patient populations (BTKi/BCL2i exposed vs naive) and different observation times, the efficacy outcomes across these regimens appear comparable, with PB uMRD rates at the end of treatment between 50% and 76%, with obinutuzumab-containing therapies achieving these rates at earlier time points. The PFS rates were high for all tested regimens and compare favorably with the currently approved treatment options of BTKi monotherapy and venetoclax-rituximab. In the Ohio State study, a median PFS of 82 months was reported after a fixed-duration therapy of just 14 months of I+V plus obinutuzumab, thus a BTKi/BCL2i-naive patient receiving this regimen in the second line might expect to have a 6-year treatment-free interval before meeting criteria for disease progression. Similar trends (although with shorter follow-up) can be observed for patients previously exposed to BTKi/BCL2i in the CLL2-BAAG trial with a median treatment duration of 15 months. With its minimal treatment duration of 30 months, the SAKK 34/17 trial withholds this opportunity of early, MRD-guided treatment discontinuations for good responders. In my view, this treatment prolongation for all patients, not only those with suboptimal responses, does not do justice to the heterogeneity (CLL biology, age, previous therapies) of a relapsed patient collective and might result in overtreatment with an increased risk for toxicities and the acquisition of resistance mutations that potentially limits retreatment options. In trials like VISION or CLARITY, a more adaptive approach with treatment durations from 14 to 15 months for patients with early uMRD to continuous treatment for those who need it was feasible and also resulted in excellent efficacy outcomes.

Different duration of BTKi plus BCL2i combinations in relapsed CLL. This figure shows the treatment duration of different published BTKi plus BCL2i (with or without obinutuzumab) combinations in relapsed CLL. The dark part of the bars indicates the minimal treatment duration, and the light part indicates the optional, MRD-guided prolongation of treatment. The table lists key demographic and outcome data from the shown trials. A, acalabrutinib; I, ibrutinib; NA, data not available; Obi, obinutuzumab; V, venetoclax; Z, zanubrutinib. References of depicted trials: Ohio State10; CLL2-BAAG6; CLL2-BZAG7; CLARITY8; VISION9; SAKK 34/171.

Different duration of BTKi plus BCL2i combinations in relapsed CLL. This figure shows the treatment duration of different published BTKi plus BCL2i (with or without obinutuzumab) combinations in relapsed CLL. The dark part of the bars indicates the minimal treatment duration, and the light part indicates the optional, MRD-guided prolongation of treatment. The table lists key demographic and outcome data from the shown trials. A, acalabrutinib; I, ibrutinib; NA, data not available; Obi, obinutuzumab; V, venetoclax; Z, zanubrutinib. References of depicted trials: Ohio State10; CLL2-BAAG6; CLL2-BZAG7; CLARITY8; VISION9; SAKK 34/171.

Despite the rather long treatment, Condoluci et al report few mutations in BCL2 and none in BTK, which is generally reassuring. However, resistance mutations were analyzed in plasma using a CAPP-seq approach that detected residual disease (ie, circulating tumor DNA) in only 3 patients at month 30. It can thus be assumed that the absence of resistance mutations at month 30 reflects an absence of detectable disease rather than an absence of resistance mutations in the CLL cells and that the rate of mutations in BCL2 and BTK might increase at the time point of disease progression.

In conclusion, the SAKK 34/17 study demonstrates high uMRD and PFS rates in an older relapsed patient population with CLL despite many early treatment discontinuations and several treatment-unrelated deaths. Replacing ibrutinib with a second-generation BTKi and allowing more time off treatment might further improve the tolerability of this regimen. The optimal duration of time-limited BTKi plus BCL2i combination treatments in relapsed CLL remains a subject of debate, but given the convincing data from several trials (see figure), there is a strong case for earlier treatment discontinuation in patients with deep remissions. Irrespective of this question, it is time to investigate these promising phase 2 approaches in randomized trials so that more efficacious time-limited options become available in the relapse setting.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.F. declares no competing financial interests.

Comments

Response to the Comment of Dr. Visentin et al.

With the obvious caveats of cross trial comparisons, the data from the IMPROVE study - when juxtaposed with the SAKK 34/17 data - further strengthens the notion that with less treatment and a more adaptive/flexible approach, better safety and efficacy outcomes can be obtained, thus doing more justice to the heterogeneity of a relapsed patient collective and hopefully reducing the risk of overtreatment and acquisition of resistance mutations.

Response to “how long should we treat relapsed CLL?” and how to improve

we read with interest the study by Condoluci et al.1 reporting the results from the SAKK 24/17 trial, in which 30 patients with relapsed-refractory (R/R) chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) received 6 months of ibrutinib (Ibr) lead-in followed by 24 months of ibrutinib plus venetoclax (I+V), and the accompanying editorial2 which interpreted the study in the context of other published studies using I+V combinations.

Surprisingly both manuscripts1,2 did not mention the IMPROVE trial that also investigated the combination of the 2 drugs3. This phase 2 MRD-driven study was designed with the intent of discontinuing treatment upon reaching uMRD4 in patients with R/R CLL treated either in monotherapy or in combination. Patients started with venetoclax (Ven) monotherapy and those achieving uMRD4 discontinued it at Cycle 12, dMRD4 patients added ibrutinib and continued I+V up to Cycle 24 Day 28/uMRD4/progression/toxicity. Patients who still had dMRD4 at Cycle 24 continued ibrutinib till progression or toxicity.

Thirty-eight patients (29% with TP53 aberrations; 79% with unmutated IGHV) started Ven. Seventeen patients (45%) with uMRD4 discontinued Ven at cycle 12 while 19 (55%) dMRD4 added ibrutinib. With I+V, 16 (84%) of 19 patients achieved uMRD4, thus stopping both drugs. This sequential MRD-guided approach led to uMRD4 in 87% (33/38) patients, which seems higher than 63% reported by Condolucci et al1.

Along this line, in the IMPROVE trial, only 2 patients (5%) did not complete treatment, including one who developed myelodysplasia during Ven monotherapy (deemed unlikely to be treatment-related). Conversely, in the SAKK 24/17 36% of the patients discontinued treatment due to AEs, a rate that is 2 to 3-fold higher than other trials with I+V in the R/R patients with CLL2,4, likely due to the prolonged exposure to both drugs, which was more limited using the IMPROVE approach. Of note, in the IMPROVE trial, only 1 and 4 patients developed atrial fibrillation and hypertension, respectively, but none of grade 3 or higher. In the SAKK 24/17 10% developed grade 3 or 4 cardiac AEs.

Given the high rates of deep remissions and the safety profile, we believe our approach is worth mentioning and considering in this context.