Key Points

Plasma clots of patients with trauma feature entirely novel fibrin β-chain cross-linking not evident in healthy controls.

Fibrin β-chain cross-links evident in plasma clots of patients with trauma are recapitulated in vitro by TG2.

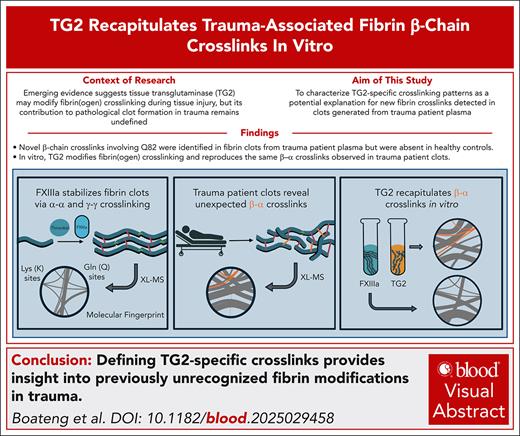

Visual Abstract

Covalent cross-linking of fibrin by the plasma transglutaminase coagulation factor XIII (FXIII) is a key determinant of blood clot stability and function. FXIII-catalyzed formation of ε-N-(γ-glutamyl)-lysyl cross-links is restricted to the fibrin γ-chain and α-chain and follows thrombin-driven fibrin polymerization. Fibrinogen is also cross-linked by tissue transglutaminase (TG2) in a reaction favoring intramolecular and intermolecular α-γ cross-linking. Emerging evidence indicates that fibrinogen is a relevant substrate of TG2 in conditions of acute tissue damage. Remarkably, beyond detection of prototypical FXIII-directed cross-links (ie, α-α, γ-γ), we identified entirely novel covalent cross-links involving the fibrinogen β-chain (ie, β-α, via FGB-Q82). Addition of TG2 to in vitro clotting reactions and analysis of fibrin(ogen) in reducing conditions revealed loss of β-chain polypeptide paired with formation of high-molecular weight β-chain species. Mass spectrometry–based cross-linking proteomic analysis of in vitro clots recapitulated the precise TG2-directed β-chain cross-links observed in clots made using plasma from patients following traumatic injury. The results indicate in vitro and ex vivo cross-linking of the fibrin β-chain and highlight a novel example of TG2 emerging as a relevant plasma transglutaminase.

Introduction

Fibrinogen circulates in plasma as a hexameric complex consisting of 2 Aα, 2 Bβ, and 2 γ chains (FGA, FGB, and FGG, respectively).1 In the first step of fibrin formation, the serine protease thrombin cleaves fibrinopeptides off the Aα and Bβ chains.1 Cross-linking of the α- and γ-chain by the plasma transglutaminase coagulation factor XIII (FXIII) plays a crucial role in stabilizing blood clots, contributing to hemostasis and wound healing.2 These cross-links are vital for providing the structural integrity necessary to prevent untimely clot dissolution.2-4 Notably, recent studies have begun to reveal additional complexities in the fibrin cross-linking process, suggesting that other transglutaminases may also contribute to clot formation, particularly under certain pathological conditions.5,6

Pioneering work by Murthy and Lorand, who isolated tissue transglutaminase (TG2) from red blood cells, documented that TG2 forms α-γ cross-links in fibrin.7 This contrasts with the primary plasma transglutaminase FXIII, which predominantly creates α-α and γ-γ cross-links.2 This discovery suggested the possibility that TG2 may play a role in fibrin(ogen) cross-linking within injured tissues and perhaps play a role in conditions of major tissue damage. Emerging experimental evidence supports the role of TG2 in tissue fibrin(ogen) cross-linking, and elevated TG2 activation has been reported in red blood cells under physiological or pathological hypoxia.8 However, biomarker-based evidence of the role of TG2-directed cross-linking of fibrin in patients is lacking. Accordingly, we sought evidence of TG2-directed fibrin cross-linking in patients with trauma, a notion fully aligned with TG2 emerging as a relevant transglutaminase in conditions of acute tissue injury.

Study design

Trauma plasma samples were obtained from the randomized COMBAT (Control of Major Bleeding After Trauma) clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01838863).9 Clots were generated for samples from 3 patients with trauma with normal fibrinolytic measurements using rapid thromboelastography. Controls were obtained from 9 healthy individuals (international review board approval no. 12-1614). After recalcification, thromboplastin was used for initiation. Clots were allowed to form over 30 minutes at 37°C. Clots were processed, and cross-linking mass spectrometry (CL-MS) proteomic analysis was performed on chromatographic fractionated peptide digests (8 fractions each). Data was searched with MSFragger10 for protein identifications and pLink2.011 for cross-link identifications. R was used for data processing, and Circos12 was used for data visualization. In vitro fibrin clots were made using purified human fibrinogen (FIB1; Enzyme Research Laboratories) or peak 1 fibrinogen (FXIII free) and human α-thrombin (Enzyme Research Laboratories) with or without recombinant human TG2 (Zedira) and analyzed using western blotting or CL-MS.6,13,14 Fibrinogen chains were detected using western blotting with polyclonal anti-fibrinogen β-chain antibody (Proteintech, catalog no. 16747-1-AP) or monoclonal anti-fibrin β-chain antibody (59D8; Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. MABS2155). Proteomic characterization was performed for the patient clots. Further details are presented in the supplemental Methods (available on the Blood website). This study was approved as part of the Collection of Whole Blood or Blood Components for Use in Research (protocol no. 12-1614) and Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (protocol no. 12-1349) for study of response of patients with trauma to treatment protocol.

Results and discussion

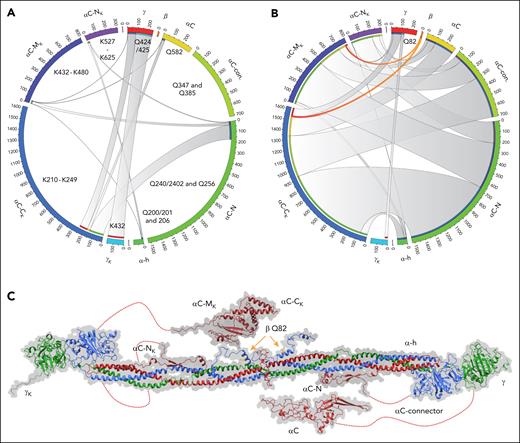

Clots were generated from 3 plasma samples of patients with trauma with normal fibrinolytic activity, as defined by thromboelastography. CL-MS analysis identified ∼250 proteins in stringently washed clots, with nearly 75% of the signal corresponding to fibrinogen chains (FGA, FGB, and FGG). Within fibrin(ogen), key glutamine cross-link sites on the Aα chain that have been documented in previous structure-function studies13,15,16 are shown in Figure 1. Corresponding lysine sites on FGA were distributed throughout the αC connector to the C-terminal portion of the αC domain (19 total, from K225 to K625). Cross-linking within the FGG C-terminus was observed. For example, the FGG residues Q424/425 were found in cross-links with FGG K432, and 8 distinct FGA lysine sites resulted in previously reported γ-γ and γ-α cross-links (Figure 1A; supplemental File 2). Overall, the results validate the capacity of CL-MS to discern precise cross-links in fibrin(ogen) formed during clotting reactions.

Chord diagram shows the cross-linking profile of fibrin clots. (A) Clots formed from healthy controls. Schematic representation of the FGG (red), FGB (orange), and FGA Q sites (yellow to green) found in cross-links (starting at the top of the circle and moving clockwise). Schematic representation of the FGG and FGA N- to C-terminal K sites (light blue to pink) (from the bottom clockwise to top). The length of the outer arc (forming the circle) is based on the maximum number of cross-link identifications across the patient samples scaled to the maximum number across patients with trauma and controls. The chord shows connectivity of Q sites (right half) to K sites (left half), and widths are based on the number of cross-links. The inner arc matches the color of the corresponding site of connectivity. (B) Clots formed from banked trauma plasma. (C) Structure of fibrinogen (PDB 3GHG) with the αC, β N-termini, and γA C-termini regions modeled. Relative position of cross-linked lysine (K) domains (matching panels A-B) shown for the 3 chains on the left half of fibrinogen and glutamine (Q) domains on the right half.

Chord diagram shows the cross-linking profile of fibrin clots. (A) Clots formed from healthy controls. Schematic representation of the FGG (red), FGB (orange), and FGA Q sites (yellow to green) found in cross-links (starting at the top of the circle and moving clockwise). Schematic representation of the FGG and FGA N- to C-terminal K sites (light blue to pink) (from the bottom clockwise to top). The length of the outer arc (forming the circle) is based on the maximum number of cross-link identifications across the patient samples scaled to the maximum number across patients with trauma and controls. The chord shows connectivity of Q sites (right half) to K sites (left half), and widths are based on the number of cross-links. The inner arc matches the color of the corresponding site of connectivity. (B) Clots formed from banked trauma plasma. (C) Structure of fibrinogen (PDB 3GHG) with the αC, β N-termini, and γA C-termini regions modeled. Relative position of cross-linked lysine (K) domains (matching panels A-B) shown for the 3 chains on the left half of fibrinogen and glutamine (Q) domains on the right half.

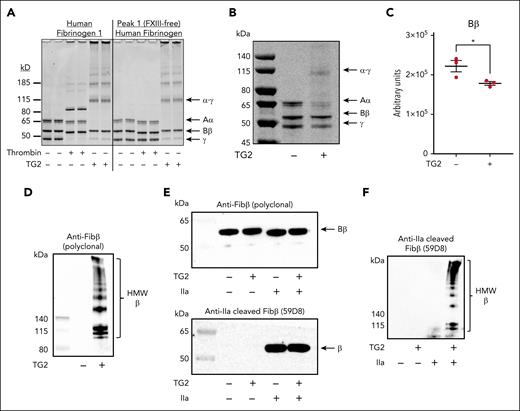

Surprisingly, we also identified several novel cross-links involving interconnection between fibrin Bβ and Aα chains in plasma clots from patients with trauma. Fibrin Bβ chain, glutamine residue 82 (FGB Q82, shown in Figure 1C) was cross-linked 14 times with 3 distinct FGA lysine residues (K437, K599, and K620) within the αC region of FGA (Figure 1B, orange chords). The identified cross-linked peptides with assigned fragmentation spectra are presented in supplemental Figure 1. FGB Q82 is shown on a modeled region of the structure (Figure 1C). These cross-links were conspicuously absent in clots generated from healthy control plasma (Figure 1A), suggesting a trauma-specific mechanism. The αC region of fibrinogen is a substrate of FXIII-dependent reactions,15,17 but to our knowledge, FGB is not a FXIII substrate. Thus, we hypothesized that the formation of FGB-FGA cross-links is mediated by an alternative transglutaminase. Traumatic tissue injury or hemolysis may liberate intracellular enzymes such as TG2.6 To determine if TG2 drives fibrin β-chain cross-linking, we generated clots in vitro using pathologically relevant levels of TG2.6 Thrombin addition to purified human fibrinogen induced fibrinopeptide A and B removal and FXIII-dependent γ-γ dimer formation (Figure 2A). In contrast, TG2 produced α-γ hybrid cross-links, even in the absence of thrombin (Figure 2A). Interestingly, while fibrinogen β-chain (∼55 kDa) levels were stable in thrombin-clotted samples, the addition of TG2 reduced fibrinogen β-chain levels even in reactions using FXIII-free fibrinogen (Figure 2A-C), consistent with observations not elaborated on in prior publications.14 We posited that this was a consequence of TG2-dependent covalent incorporation of FGB into larger complexes. Indeed, a polyclonal FGB-selective antibody detected numerous high molecular weight (HMW) bands in TG2–cross-linked fibrin (Figure 2D). To assure these HMW bands were indeed β-chain, we used a monoclonal antibody (59D8) selective for a cryptic epitope in the fibrinogen β-chain18 revealed only after thrombin proteolysis (Figure 2E). Importantly, the 59D8 monoclonal antibody detected HMW fibrin(ogen) β-chain in thrombin-clotted fibrinogen in the presence of TG2 (Figure 2F). The results suggest that TG2 covalently incorporates fibrin(ogen) β-chain into HMW complexes in the presence or absence of thrombin.

TG2 cross-links the fibrinogen β-chain to form HMW complexes. (A) Purified human fibrinogen (FIB1) and FXIII-free fibrinogen (peak 1) were incubated with thrombin (ie, to initiate fibrin polymer formation and FXIII-mediated cross-linking) or recombinant human TG2, as described previously.14 Reduced samples were resolved using sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and total protein was visualized with Coomassie Blue. (B) FIB1 (2 mg/mL) was cross-linked by TG2 (25 μg/mL), and reduced samples were resolved using SDS-PAGE and visualized with SimplyBlue. A representative gel of at least 3 independent experiments is shown. (C) Fibrinogen β-chain was quantified using densitometry. (D) Representative western blot for fibrinogen β-chain shows HMW cross-linked β-chain in fibrinogen cross-linked by TG2. (E) Thrombin (1 U/mL) or TG2 (25 μg/mL) was added to FIB1 (2 mg/mL). Representative western blots show fibrinogen β-chain detected using western blotting with the polyclonal anti-fibrinogen β-chain antibody (top) or monoclonal anti-fibrin β-chain (59D8) antibody (bottom). (F) Representative western blots show HMW fibrinogen β-chain in fibrinogen cross-linked by TG2 detected using western blotting with the anti-fibrin β-chain (58D8) antibody. For panels D-F, membranes were cut and probed with distinct primary antibody concentrations to resolve β-chain and HMW cross-linked β-chain.

TG2 cross-links the fibrinogen β-chain to form HMW complexes. (A) Purified human fibrinogen (FIB1) and FXIII-free fibrinogen (peak 1) were incubated with thrombin (ie, to initiate fibrin polymer formation and FXIII-mediated cross-linking) or recombinant human TG2, as described previously.14 Reduced samples were resolved using sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and total protein was visualized with Coomassie Blue. (B) FIB1 (2 mg/mL) was cross-linked by TG2 (25 μg/mL), and reduced samples were resolved using SDS-PAGE and visualized with SimplyBlue. A representative gel of at least 3 independent experiments is shown. (C) Fibrinogen β-chain was quantified using densitometry. (D) Representative western blot for fibrinogen β-chain shows HMW cross-linked β-chain in fibrinogen cross-linked by TG2. (E) Thrombin (1 U/mL) or TG2 (25 μg/mL) was added to FIB1 (2 mg/mL). Representative western blots show fibrinogen β-chain detected using western blotting with the polyclonal anti-fibrinogen β-chain antibody (top) or monoclonal anti-fibrin β-chain (59D8) antibody (bottom). (F) Representative western blots show HMW fibrinogen β-chain in fibrinogen cross-linked by TG2 detected using western blotting with the anti-fibrin β-chain (58D8) antibody. For panels D-F, membranes were cut and probed with distinct primary antibody concentrations to resolve β-chain and HMW cross-linked β-chain.

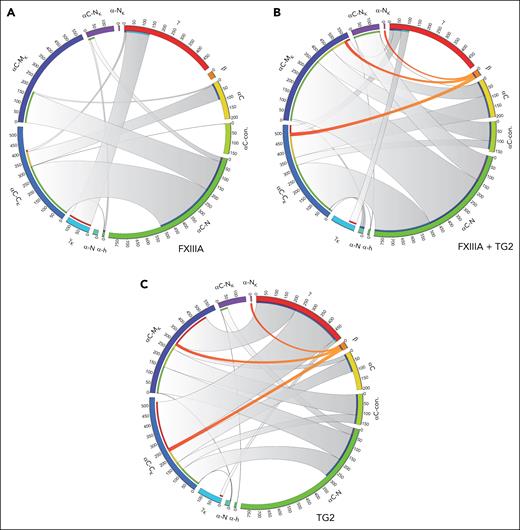

Next, we generated a comprehensive map of the cross-linking profile of these clots using CL-MS. Thrombin-clotted (FXIII-cross-linked) fibrinogen displayed a pattern dominated by FGA Q256 cross-linking to αC-C K sites (109 identified across 3 samples) and FGG Q424/425 cross-linking to K432 (99 IDs), represented by gray chords in Figure 3A. Notably, FGB cross-links were conspicuously absent in clots made with only thrombin (and endogenous FXIII). The addition of TG2 dramatically altered the cross-linking profile. With the exception of a few FGA-FGA cross-links (eg, Q347-K238, Q347-K625), the addition of TG2 produced all the Q and K cross-link categories observed in trauma clots, including increased Q240/242 cross-linking in the N-termini of the αC region (αC-N; Figure 3), FGG to FGA cross-linking (alongside a reduction in FGG-FGG), and most notably, FGB Q82 cross-links to multiple FGA αC sites (Figure 3B). TG2 also produced cross-links in all categories in reactions with FXIII-free fibrinogen, with a drastic shift toward FGG-FGA cross-links at the expense of FGA-FGA cross-links (Figure 3C). Importantly, prototype FGB Q82 cross-links observed in patients with trauma were produced by TG2 even in the absence of FXIII. Collectively, the results indicate that TG2 dramatically shifts fibrin(ogen) cross-linking patterns, including the formation of unique FGB Q82 cross-links. These same cross-links were discovered in clots from patients with trauma but not in clots generated from healthy plasma. Indeed, TG2 plasma levels were elevated in the plasma of patients with trauma (n = 32) compared with healthy control plasma (1.3 ng/mL) and exhibited a trend toward increase with the severity of trauma (new injury severity score [NISS] = 1, 9.4 ± 9.5 ng/mL vs NISS ≥ 10, 21.4 ± 23.2 ng/mL, P = .09). The results are consistent with TG2 emerging as a relevant plasma transglutaminase in the context of trauma.

Chord diagram shows the cross-linking profile of in vitro fibrin clots formed with FXIIIA and TG2. (A) Cross-linking pattern of FIB1 with copurified FXIIIA. Schematic representation of the FGG (red), FGB (orange), and FGA Q sites (yellow to green) found in cross-links (starting at the top of the circle and moving clockwise). Schematic representation of the FGG and FGA N- to C-terminal K sites (light blue to pink) (from the bottom clockwise to top). The length of the outer arc is kept constant and is based on the maximum number of cross-links observed at that site across conditions. The chord widths are based on the number of cross-links. (B) Cross-linking pattern of FIB with copurified FXIIIA and human TG2. (C) Cross-linking pattern of FXIIIA-free FIB (peak 1) with human TG2.

Chord diagram shows the cross-linking profile of in vitro fibrin clots formed with FXIIIA and TG2. (A) Cross-linking pattern of FIB1 with copurified FXIIIA. Schematic representation of the FGG (red), FGB (orange), and FGA Q sites (yellow to green) found in cross-links (starting at the top of the circle and moving clockwise). Schematic representation of the FGG and FGA N- to C-terminal K sites (light blue to pink) (from the bottom clockwise to top). The length of the outer arc is kept constant and is based on the maximum number of cross-links observed at that site across conditions. The chord widths are based on the number of cross-links. (B) Cross-linking pattern of FIB with copurified FXIIIA and human TG2. (C) Cross-linking pattern of FXIIIA-free FIB (peak 1) with human TG2.

The results provide the proof-of-concept that fibrin(ogen) is a relevant in vivo TG2 substrate and suggest that TG2 may be an underappreciated driver of fibrin(ogen) cross-linking in settings of acute tissue injury. The identification of β-chain cross-linking in our study adds a new dimension to these findings, indicating that TG2 can drive more diverse cross-linking patterns than previously recognized. These findings also raise the possibility that TG2 may partially compensate for the absence of FXIII in vivo, potentially playing a role in both traditional hemostasis and wound healing.19,20 Our experiments, including those using FXIII-free fibrinogen, demonstrated that TG2 alone can generate robust fibrin cross-links, many of which overlap with those formed by FXIII, whereas others are distinct. Notably, these include unique linkages involving FGB Q82, underscoring the potential of TG2 to contribute to fibrin(ogen) stabilization independent of FXIII. The precise effect of these unique TG2-mediated β-chain cross-links on fibrin(ogen) effector function is unknown but may encompass effects on fibrin(ogen) hemostatic and inflammatory functions,21 both of which are pivotal during trauma-induced coagulopathy. Our findings inform on future site-directed mutagenesis and production of mutant fibrinogen proteins to uncover the effects of β-chain cross-links. Similarly, strategies used to generate mice expressing FXIII-resistant fibrinogen22 may inform the design of mice expressing fibrinogen that is distinctly resistant to cross-links uniquely imposed by TG2, such as those involving FGB Q82.

Collectively, we report the novel finding of fibrin β-chain cross-linking, driven not by the canonical plasma transglutaminase FXIII but by TG2. Using CL-MS and western blotting, we identified β-α cross-links in fibrin clots formed in vitro using purified fibrinogen and TG2. Remarkably, these precise cross-links were evident in clots generated ex vivo using plasma from patients with trauma, strongly suggesting a genuine contribution of TG2 to fibrin(ogen) cross-linking in the context of trauma-induced coagulopathy. This transformational discovery paves the way for further investigations into the differential roles of transglutaminase isozymes in clot formation and their contributions to the altered hemostatic balance observed in trauma and other disease settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend special thanks to the entire trauma team and to the patients and their families.

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01 DK120289 and R01 DK136733; J.L.), support from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Institute of Food and Agriculture, and the Albert C. and Lois E. Dehn Endowment to Michigan State University for Veterinary Medicine (Pathobiology and Diagnostic Investigation; J.L.). Funding was received from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), NIH (grant R33CA183685; K.H.), and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, NIH (grant RM1GM131968; K.H., A.D., G.M., and M.C) and the NCI/NIH University of Colorado Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA046934; K.H and A.D.).

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the USDA.

Authorship

Contribution: N.K.K.B., R.W., L.P., L.S., J.L., J.R., A.D., and K.H. designed and performed research and analyzed data; N.K.K.B., J.L., A.D., and K.H. drafted the manuscript; M.C. and E.M. provided samples from patients with trauma; and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.D. and K.H. are founders of Omix Technologies Inc. A.D. is a founder of Altis Biosciences LLC; and a scientific advisory board member for Hemanext Inc and Macopharma Inc. E.M. has received financial support from HemoSonics, Humacyte, and Prytime Medical. None of these relationships had an influence on this work. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Kirk Hansen, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, University of Colorado School of Medicine, 12901 E 17th Ave, RC1-S Room 9115, Aurora, CO 80045; email: kirk.hansen@cuanschutz.edu; and James Luyendyk, Department of Pathobiology and Diagnostic Investigation, Michigan State University, 1129 Farm Ln, 253 FST, East Lansing, MI 48824; email: luyendyk@msu.edu.

References

Author notes

Raw mass spectrometry data and result files have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange consortium (identifiers PXD062639 and PXD062688).

Original data are available from the corresponding authors, Kirk Hansen (kirk.hansen@cuanschutz.edu) or James Luyendyk (luyendyk@msu.edu), on request. Global proteomic results can be found in the online version of this article.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal