Abstract

Sixty patients with Hodgkin's disease, refractory to or at first recurrence after chemotherapy, received cytoreductive therapy followed by high-dose etoposide, cyclophosphamide and either total body irradiation or carmustine and autografting (median follow-up, 3.6 years; range, 1.1 to 7.5 years). A matched conventional salvage group of 103 patients was selected from patients treated at Stanford University Medical Center between January 1976 and January 1989 (median follow-up, 10.3 years; range, 3.0 to 15.7 years). Overall survival (OS), event-free survival (EFS), and freedom from progression (FFP) at 4 years follow-up favored patients who received high-dose therapy compared with conventional salvage treatment (OS: 54% v 47%, P = .25; EFS: 53% v 27%, P < .01; FFP: 62% v 32%, P < .01). In Cox regression analysis, response to cytoreductive or salvage therapy and B symptoms at relapse were the most important predictors of OS. The use of high-dose therapy at relapse, a longer duration of remission, and favorable response to cytoreductive or salvage therapy were most predictive of superior FFP and EFS. These data from a single institution comparing conventional and high-dose therapy in matched patients demonstrate an advantage for high-dose therapy and autografting in the sustained control of Hodgkin's disease. As with primary therapy, it is difficult to demonstrate a statistically significant survival advantage, despite an apparently superior cure rate. However, patients failing induction therapy or relapsing within 1 year benefited significantly from high-dose therapy by all outcome measures (OS, EFS, FFP). As the transplant-related mortality rates decline in Hodgkin's disease, it is predicted that cure rates and late effects will become ultimate determinants of the success of high-dose therapy and autografting.

A SUBSET OF PATIENTS with advanced stage Hodgkin's disease will fail induction therapy or relapse after chemotherapy.1 Treatment results with second-line chemotherapy have generally been disappointing, particularly in patients who failed induction therapy or who had a brief duration of remission.2-4 In the last decade, high-dose therapy (HDT) with autologous stem cell support (autografting) has been used with increasing frequency at first relapse. In contrast to historical salvage treatment data, the results of high-dose therapy appear promising, as a significant number of patients enter an apparent sustained remission.5-15 However, few studies have directly compared high-dose therapy regimens and conventional salvage strategies.

It is difficult to compare high-dose therapy results with those of conventional therapy for several reasons. Patients receiving high-dose therapy are selected on the basis of age and other factors. Results from chemotherapy series differ in both the primary and second-line therapies used, some of which are no longer considered to be optimal therapy. In addition, the autografting series are mixed, with early series including less favorable patients with multiple relapses. The current study was undertaken to compare the characteristics and outcome between patients with refractory or relapsed Hodgkin's disease who were treated in first relapse with high-dose therapy and autografting and a matched historical group of patients who were managed with conventional treatment strategies.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Selection of Study Groups

The high-dose therapy group consisted of patients who were treated at Stanford University Medical Center (SUMC) with high-dose therapy and autografting for Hodgkin's disease that was refractory to induction chemotherapy or in first relapse after chemotherapy. The comparison group consisted of a matched group of patients who were treated with conventional therapy with curative intent at SUMC. The conventional salvage group included those patients who failed both primary radiotherapy and a course of salvage chemotherapy. Patients were identified through a search of the computerized Hodgkin's disease data base in the Division of Oncology. The conventional therapy group was selected to mirror the general characteristics of the high-dose therapy group. These characteristics included (1) initial disease stage II-IV; (2) age at relapse between 15 and 45 years; and (3) failure of induction chemotherapy or in first relapse after chemotherapy. The time interval for conventional therapy was restricted to January 1976 through January 1989, a period when doxorubicin chemotherapy had become available and before the frequent use of high-dose therapy at SUMC. All treatment was given at SUMC.

Conventional Salvage Therapy

Conventional salvage therapy generally consisted of combination chemotherapy that was noncross-resistant to the original induction treatment; consideration was given to retreatment with the induction regimen in patients who had been in remission longer than 1 year before relapse. Consolidative radiotherapy was often administered to bulky sites of recurrent disease. Patients not treated with curative intent, such as those who received single agent chemotherapy or nonmyelosuppressive regimens, were not included in this analysis. Treatment generally continued until a maximum response was attained. Growth factors were not available during the period when the conventional therapy patients were treated.

High-Dose Therapy and Autografting

Treatment with high-dose therapy with autografting for Hodgkin's disease started at SUMC in December of 1987. Patients who met the following criteria were considered for treatment: age 15 to 55 years, refractory or recurrent Hodgkin's disease with a projected cure rate of less than 25% with conventional therapy, and no contraindication to the planned treatment. Most patients received cytoreductive chemotherapy, usually two to three cycles, in an attempt to achieve a state of minimal disease before high-dose therapy and autografting. If patients had received seven- or eight-drug induction chemotherapy and had a disease-free interval of 12 months or less, then cisplatin, cytarabine, and dexamethasone (DHAP) was given as cytoreductive treatment.16 For patients with a disease-free interval of longer than 1 year, or initial treatment with a four-drug regimen, either mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone (MOPP),17 doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (ABVD),18 or a combination of the two regimens was recommended. Response was assessed before proceeding with high-dose therapy.

Peripheral blood progenitor cells (PBPC), collected by apheresis, were given alone or in combination with harvested bone marrow.19 Patients received one of two preparatory regimens depending on prior therapy. Carmustine [BCNU] (15 mg/kg, not to exceed 550 mg/m2), etoposide [VP-16] (60 mg/kg), and cyclophosphamide [Cy] (100 mg/kg), were given to patients with prior chest radiation greater than 20 Gy or pelvic radiation. All other patients received fractionated total body radiation (fTBI), 12 Gy in 10 fractions, with identical doses and scheduling of etoposide and cyclophosphamide. Involved field irradiation was given pre or posttransplantation to selected patients.

Study Parameters

The following information was extracted from clinic or hospital records of the high-dose therapy and conventional salvage patients: stage of disease at diagnosis, presence of B symptoms at diagnosis, duration of remission (induction failure, ≤12 months, >12 months), presence of B symptoms at relapse, extent of disease at relapse, age at relapse, number of extranodal sites of disease at relapse, any prior radiotherapy, treatment with radiotherapy alone at diagnosis, relapse in site of prior radiotherapy, response to salvage treatment in the conventional salvage group and response to cytoreductive treatment in the high-dose therapy group. In addition, the following information was collected on patients in the conventional salvage group: amount and type of chemotherapy delivered in the first 12 weeks of salvage therapy and total months of MOP(P) chemotherapy before relapse.

Induction failure was defined as progression during initial therapy or relapse within 2 months of completion of treatment. Duration of remission was measured from the end of treatment with chemotherapy to the date of relapse. For patients receiving radiotherapy alone as primary therapy, remission duration was calculated from the end of treatment with salvage chemotherapy to the date of relapse. The response to cytoreductive or salvage therapy was classified as (1) complete if all previously abnormal radiographs returned to normal and previously involved bone marrow was normal on repeat examination; (2) minimal disease (MD) if there was more than a 75% reduction in a bulky (>10 cm) tumor mass, 2 cm or less maximum horizontal diameter of a lymph node, and less than 10% bone marrow involvement; (3) partial if there was greater than a 50% reduction in the sum of the perpendicular diameters of tumor masses, but less than a MD status as defined above; and (4) none if patients did not meet any of the above criteria.

The amount of chemotherapy delivered in the first 12 weeks of salvage treatment was expressed as the percentage of prescribed dose of a standard regimen, eg, MOP(P) or ABVD, that was actually received. Each agent counted equally towards the total percentage delivered. Categories of treatment were designated as follows: (1) 85% to 100%; (2) 50% to 85%; (3) <50% of a standard regimen; or (4) salvage with radiotherapy alone.

Statistical Analysis

Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the beginning of salvage/cytoreductive therapy to the date of death or last follow-up. Freedom from progression (FFP) was measured from the beginning of salvage/cytoreductive therapy to the date of relapse (if any). Toxic or intercurrent deaths were censored with this endpoint. Event-free survival (EFS) considered toxic or intercurrent deaths as well as relapses as events. Survival analyses were performed using the method of Kaplan and Meier.20 Differences in survival between groups were identified by the generalized log-rank analysis.21 The prognostic significance of variables was calculated using backwards selection Cox multivariate regression.22

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Conventional salvage.The conventional salvage group consisted of 103 patients with Hodgkin's disease either in first relapse or refractory to chemotherapy who began salvage treatment between January 1976 and January 1989. As shown in Table 1, most patients (70%) had stage III-IV disease at diagnosis, and about half had B symptoms. Forty patients (39%) were treated initially with chemotherapy only, 39 (38%) received chemotherapy and radiation, and 24 (23%) received radiotherapy alone. As previously stated, all patients initially treated with radiotherapy alone had also failed a course of salvage chemotherapy. Most patients either failed induction therapy (25%) or relapsed ≤12 months of chemotherapy (34%). At relapse, most patients (58%) had evidence of extensive disease, but a minority (18%) had B symptoms. Eighty-six patients (84%) had received radiotherapy at some time before relapse, and 59 (57%) relapsed within a site previously treated with radiotherapy.

Characteristics of High-Dose Therapy and Conventional Salvage Therapy Groups

| Characteristic . | CS . | HDT . | Chi square* . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | n (%) . | n (%) . | P . |

| Total no. | 103 | 60 | |

| Initial disease stage | |||

| II | 31 (30) | 20 (33) | |

| III | 43 (42) | 18 (30) | .53 |

| IV | 39 (28) | 22 (37) | |

| Initial B symptoms | |||

| Present | 55 (53) | 40 (67) | .14 |

| Absent | 48 (47) | 20 (33) | |

| Initial radiotherapy only | |||

| Yes | 24 (23) | 8 (13) | |

| No | 79 (77) | 52 (87) | .18 |

| Duration of remission | |||

| Induction failure | 26 (25) | 13 (22) | |

| ≤12 months | 35 (34) | 25 (42) | .61 |

| >12 months | 42 (31) | 22 (37) | |

| Stage at relapse | |||

| I | 18 (18) | 3 (5) | I/II v |

| II | 25 (24) | 22 (37) | III/IV |

| III | 11 (11) | 12 (20) | P = 1.0 |

| IV | 48 (47) | 23 (38) | |

| B symptoms at relapse | |||

| Present | 18 (18) | 28 (47) | <.01 |

| Absent | 83 (82) | 32 (53) | |

| Prior radiotherapy | |||

| Yes | 86 (84) | 30 (50) | <.01 |

| No | 17 (16) | 30 (50) | |

| Relapse in irradiated site | |||

| Yes | 59 (57) | 22 (37) | .02 |

| No | 44 (43) | 38 (63) | |

| No. of extranodal sites | |||

| None | 45 (44) | 31 (52) | 0 v 1-3; |

| One | 43 (42) | 19 (32) | P = .44 |

| Two | 13 (13) | 10 (17) | |

| Three | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| Age at relapse | |||

| Range | 15-44 | 16-45 | |

| Median | 26 | 28 | |

| Type of salvage therapy | |||

| Full dose chemotherapy | 28 (28) | ||

| Moderate dose | 50 (50) | ||

| Attenuated dose | 9 (9) | ||

| Radiotherapy alone | 13 (13) | ||

| Response to salvage therapy | |||

| Complete/minimal disease | 68 (66) | 47 (78) | CR/MD v |

| Partial | 10 (10) | 12 (20) | PR/NR; |

| None | 25 (24) | 1 (2) | P = .14 |

| Characteristic . | CS . | HDT . | Chi square* . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | n (%) . | n (%) . | P . |

| Total no. | 103 | 60 | |

| Initial disease stage | |||

| II | 31 (30) | 20 (33) | |

| III | 43 (42) | 18 (30) | .53 |

| IV | 39 (28) | 22 (37) | |

| Initial B symptoms | |||

| Present | 55 (53) | 40 (67) | .14 |

| Absent | 48 (47) | 20 (33) | |

| Initial radiotherapy only | |||

| Yes | 24 (23) | 8 (13) | |

| No | 79 (77) | 52 (87) | .18 |

| Duration of remission | |||

| Induction failure | 26 (25) | 13 (22) | |

| ≤12 months | 35 (34) | 25 (42) | .61 |

| >12 months | 42 (31) | 22 (37) | |

| Stage at relapse | |||

| I | 18 (18) | 3 (5) | I/II v |

| II | 25 (24) | 22 (37) | III/IV |

| III | 11 (11) | 12 (20) | P = 1.0 |

| IV | 48 (47) | 23 (38) | |

| B symptoms at relapse | |||

| Present | 18 (18) | 28 (47) | <.01 |

| Absent | 83 (82) | 32 (53) | |

| Prior radiotherapy | |||

| Yes | 86 (84) | 30 (50) | <.01 |

| No | 17 (16) | 30 (50) | |

| Relapse in irradiated site | |||

| Yes | 59 (57) | 22 (37) | .02 |

| No | 44 (43) | 38 (63) | |

| No. of extranodal sites | |||

| None | 45 (44) | 31 (52) | 0 v 1-3; |

| One | 43 (42) | 19 (32) | P = .44 |

| Two | 13 (13) | 10 (17) | |

| Three | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| Age at relapse | |||

| Range | 15-44 | 16-45 | |

| Median | 26 | 28 | |

| Type of salvage therapy | |||

| Full dose chemotherapy | 28 (28) | ||

| Moderate dose | 50 (50) | ||

| Attenuated dose | 9 (9) | ||

| Radiotherapy alone | 13 (13) | ||

| Response to salvage therapy | |||

| Complete/minimal disease | 68 (66) | 47 (78) | CR/MD v |

| Partial | 10 (10) | 12 (20) | PR/NR; |

| None | 25 (24) | 1 (2) | P = .14 |

Chi square test of distribution of variables between HDT and CS groups.

Salvage therapy for most patients consisted of chemotherapy (73%) or chemotherapy and radiotherapy (14%). Thirteen patients (13%) received radiotherapy alone (Table 2). Doxorubicin-based chemotherapy was used most often (67%), while a smaller portion of patients received a MOP(P)-based treatment (15%) or other chemotherapy regimen (5%). The majority of patients did not receive full doses of a standard salvage chemotherapy regimen. Only 28 patients (28%) received greater than 85% of optimal doses, while 50 (50%) received between 50% to 85%. The remainder received less than 50% of optimal doses. Most patients had sensitive disease as 68 (66%) patients achieved a CR or MD. Twenty-five (24%) did not respond to salvage treatment.

Treatment of 103 Conventional Salvage Therapy Patients

| . | No. . |

|---|---|

| Initial treatment | |

| Radiation only | 24 |

| Chemotherapy | 40 |

| Combined modality | 39 |

| First chemotherapy course | |

| MOP(P)* | 68 |

| PAVe† | 17 |

| PAVe/ABVD† | 8 |

| MOPP/ABV(D)‡ | 5 |

| ABVD* | 5 |

| Salvage therapy at relapse | |

| Doxorubicin-based therapy | 69 |

| MOP(P)-based therapy | 16 |

| Other chemotherapy | 5 |

| Chemotherapy and radiotherapy | 14 |

| Radiotherapy only | 13 |

| . | No. . |

|---|---|

| Initial treatment | |

| Radiation only | 24 |

| Chemotherapy | 40 |

| Combined modality | 39 |

| First chemotherapy course | |

| MOP(P)* | 68 |

| PAVe† | 17 |

| PAVe/ABVD† | 8 |

| MOPP/ABV(D)‡ | 5 |

| ABVD* | 5 |

| Salvage therapy at relapse | |

| Doxorubicin-based therapy | 69 |

| MOP(P)-based therapy | 16 |

| Other chemotherapy | 5 |

| Chemotherapy and radiotherapy | 14 |

| Radiotherapy only | 13 |

High-dose therapy.Between March 25, 1988 and October 27, 1993, 60 patients with Hodgkin's disease in first relapse or refractory to chemotherapy were treated with high-dose therapy and autografting. The characteristics of the study group are shown in Tables 1 and 3. About two thirds had stage III or IV disease at diagnosis, and an equal percentage had B symptoms. Thirty patients (50%) were treated initially with chemotherapy, 22 (37%) received radiotherapy and chemotherapy, and eight (13%) received radiotherapy alone.

Treatment of High-Dose Therapy Patients

| . | No. . |

|---|---|

| Initial treatment | |

| Chemotherapy only | 30 |

| Chemotherapy and radiotherapy | 22 |

| Radiotherapy only | 8 |

| First chemotherapy course | |

| MOPP/ABV(D)3-150 | 25 |

| ABVD3-151 | 13 |

| MOP(P)†/CMOPP3-152 | 11 |

| Stanford Vρ | 4 |

| PAVe3-155 | 4 |

| NOVP¶, DHAP3-151 | 2 |

| MOP(P)/PAVe3-155 | 1 |

| Cytoreductive therapy before HDT | |

| DHAP3-151 | 17 |

| MOP(P)3-151 | 13 |

| MOPP/ABV(D)3-150 | 8 |

| Radiotherapy | 7 |

| Stanford Vρ | 6 |

| ABVD3-151 | 5 |

| Other chemotherapy | 4 |

| . | No. . |

|---|---|

| Initial treatment | |

| Chemotherapy only | 30 |

| Chemotherapy and radiotherapy | 22 |

| Radiotherapy only | 8 |

| First chemotherapy course | |

| MOPP/ABV(D)3-150 | 25 |

| ABVD3-151 | 13 |

| MOP(P)†/CMOPP3-152 | 11 |

| Stanford Vρ | 4 |

| PAVe3-155 | 4 |

| NOVP¶, DHAP3-151 | 2 |

| MOP(P)/PAVe3-155 | 1 |

| Cytoreductive therapy before HDT | |

| DHAP3-151 | 17 |

| MOP(P)3-151 | 13 |

| MOPP/ABV(D)3-150 | 8 |

| Radiotherapy | 7 |

| Stanford Vρ | 6 |

| ABVD3-151 | 5 |

| Other chemotherapy | 4 |

The majority failed induction therapy (22%) or relapsed ≤12 months after primary chemotherapy (42%). At relapse, most had evidence of extensive (stage III or IV) disease (58%), and half had B symptoms. Thirty patients (50%) had received radiotherapy before relapse, and 22 (37%) patients relapsed in a previously irradiated site. Cytoreductive therapy consisted of chemotherapy alone (78%), chemotherapy with radiation therapy (10%), or radiotherapy alone (12%). Forty-seven (78%) had sensitive disease at relapse, achieving either a state of CR or MD with cytoreductive therapy. Twenty patients received fTBI/VP-16/Cy and 40 received BCNU/VP-16/Cy as the preparatory regimen. Forty-one patients received both bone marrow and PBPC, 17 received PBPC only, and two received bone marrow alone. Three patients received posttransplant radiotherapy.

One criticism of the generally favorable results of high-dose therapy is that patients are highly selected. Table 1 shows that high-dose therapy patients had generally more favorable characteristics; a significantly greater portion of patients had not relapsed in a site of prior radiation (63% v 43%, P = .02), and a greater proportion of high-dose therapy patients had sensitive disease at relapse (78% v 66%, P = .14). However, a greater number of high-dose therapy patients had B symptoms at relapse (47% v 18%, P < .01).

Survival Analysis

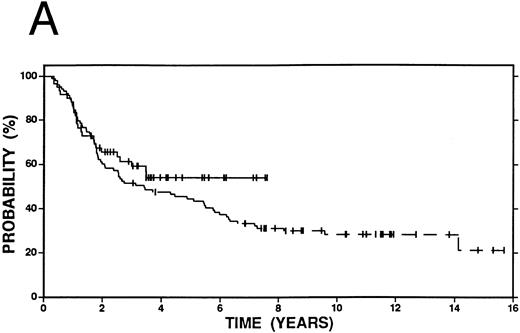

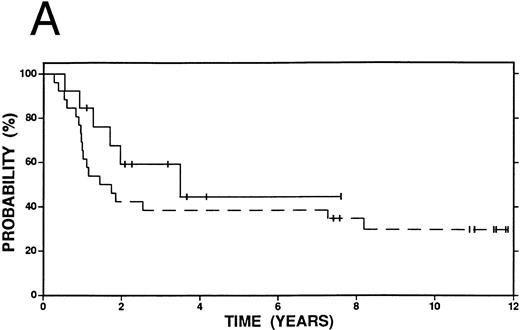

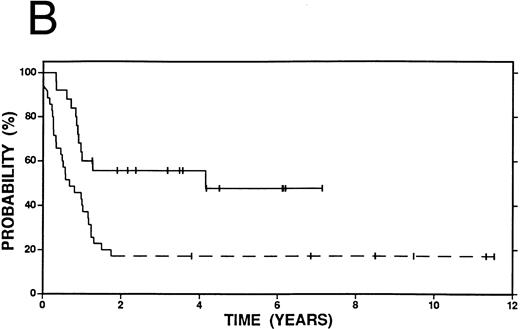

Conventional salvage.The median follow-up of survivors in the conventional salvage group was 10.3 years (range, 3.0 to 15.7 years). The 4-year overall survival was 47% (Fig 1A), but only 32% were free from progression at the time. The EFS was 27% at 4 years (Fig 1B). The causes of death included 60 due to Hodgkin's disease, 7 due to a second malignancy, 4 due to cardiac disease, 2 due to infections, and 1 due to hemorrhage. The results of Cox regression analysis are shown in Table 4.

Survival in Hodgkin's disease patients with refractory disease or in first relapse treated with either high-dose therapy and autografting (n = 60, solid line) or conventional salvage therapy (n = 103, dashed line). (A) Overall survival. Log-rank P = .25. (B) Event-free survival. Log-rank P < .01.

Survival in Hodgkin's disease patients with refractory disease or in first relapse treated with either high-dose therapy and autografting (n = 60, solid line) or conventional salvage therapy (n = 103, dashed line). (A) Overall survival. Log-rank P = .25. (B) Event-free survival. Log-rank P < .01.

Cox Regression Analysis: Conventional Salvage Therapy Patients

| . | OS . | EFS . |

|---|---|---|

| . | P . | P . |

| All variables | ||

| Response to salvage therapy | <.01 | <.01 |

| Months of prior MOP(P) chemotherapy | .05 | NS |

| Duration of remission | NS | <.01 |

| Age at relapse | .02 | NS |

| B symptoms at relapse | .12 | NS |

| Percentage of optimal chemotherapy at relapse | .04 | .02 |

| Radiation therapy only at relapse | <.01 | .05 |

| Stage of disease at relapse | .03 | NS |

| Excluding response | ||

| Months of prior MOP(P) chemotherapy | .02 | .16 |

| Duration of remission | .07 | <.01 |

| Age at relapse | .15 | NS |

| B symptoms at relapse | .01 | NS |

| Percentage of optimal chemotherapy at relapse | .05 | <.01 |

| Radiation therapy only at relapse | .17 | .02 |

| . | OS . | EFS . |

|---|---|---|

| . | P . | P . |

| All variables | ||

| Response to salvage therapy | <.01 | <.01 |

| Months of prior MOP(P) chemotherapy | .05 | NS |

| Duration of remission | NS | <.01 |

| Age at relapse | .02 | NS |

| B symptoms at relapse | .12 | NS |

| Percentage of optimal chemotherapy at relapse | .04 | .02 |

| Radiation therapy only at relapse | <.01 | .05 |

| Stage of disease at relapse | .03 | NS |

| Excluding response | ||

| Months of prior MOP(P) chemotherapy | .02 | .16 |

| Duration of remission | .07 | <.01 |

| Age at relapse | .15 | NS |

| B symptoms at relapse | .01 | NS |

| Percentage of optimal chemotherapy at relapse | .05 | <.01 |

| Radiation therapy only at relapse | .17 | .02 |

Other variables entered into the analysis include: stage at initial diagnosis, B symptoms at initial diagnosis, initial treatment with radiotherapy alone, stage at relapse, number of extra nodal disease sites at relapse, reinduction with the initial chemotherapy regimen, prior radiotherapy, relapse in site of prior radiotherapy.

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; EFS, event-free survival; not significant (NS): P > .20.

In the model that excluded response (Table 4), the percentage of optimal chemotherapy doses received at time of salvage treatment predicted for longer OS, EFS, and FFP. The overall survival at 4 years was 68% for those patients who received >85% of a standard regimen, versus 42% for those who received between 50% to 85%, and 33% for those who received <50%. Similar trends were observed in EFS and FFP at 4 years (EFS: 46% v 20% v 11%, FFP: 55% v 22% v 11%, respectively).

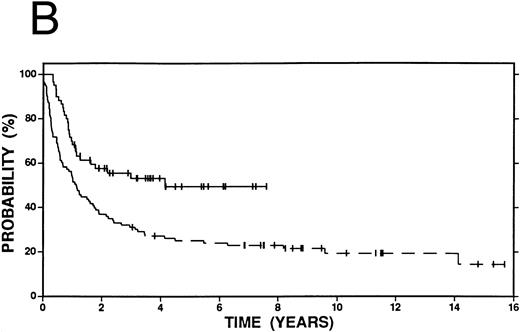

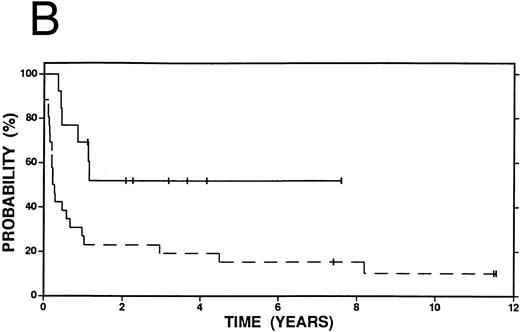

Survival in patients with an initial duration of remission longer than 12 months treated at relapse with either high-dose therapy and autografting (solid line, n = 22) or conventional salvage therapy (n = 42, dashed line). (A) Overall survival. Log-rank P < .20. (B) Event-free survival. Log-rank P < .20.

Survival in patients with an initial duration of remission longer than 12 months treated at relapse with either high-dose therapy and autografting (solid line, n = 22) or conventional salvage therapy (n = 42, dashed line). (A) Overall survival. Log-rank P < .20. (B) Event-free survival. Log-rank P < .20.

Figures 2 4 show survival curves according to initial remission duration. Sixty-two percent of patients with a remission duration longer than 12 months are alive at 4 years compared with only 38% of those who failed induction therapy or who had a shorter remission (P = .19). Similar differences in EFS and FFP are also observed at 4 years (EFS 40% v 19%, P < .01; FFP 51% v 19%, P < .01).

High-dose therapy and autografting.The median follow-up of the high-dose therapy group was 3.6 years (range, 1.1 to 7.5 years). Fifty-four percent of the group was still alive at 4 years (Fig 1A), and 62% of the group was free from progressive Hodgkin's disease. The event-free survival at 4 years was 53% (Fig 1B). The causes of death included 19 due to Hodgkin's disease, one due to graft failure, one due to respiratory failure, one from diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, two from veno-occlusive disease, and one from interstitial pneumonitis. There were no cases of treatment-related leukemia or myelodysplasia.

In Cox regression analysis (Table 5), the most significant variable predictive of OS, EFS, or FFP in this high-dose therapy group was response to cytoreductive therapy. Sixty-eight percent of the patients who achieved a CR or MD were alive at 4 years, compared with 9% of those with a partial response and none who did not have responsive disease. In the Cox regression model that excluded the variable coding for response to cytoreductive therapy, the presence of B symptoms at relapse was most predictive of OS, FFP, and EFS.

Cox Regression Analysis: High-Dose Therapy Patients

| . | OS . | EFS . |

|---|---|---|

| . | P . | P . |

| All variables | ||

| Response to cytoreductive therapy | <.01 | <.01 |

| B symptoms at relapse | .06 | .03 |

| Excluding response | ||

| B symptoms at relapse | .01 | <.01 |

| Initial disease stage | NS | .12 |

| . | OS . | EFS . |

|---|---|---|

| . | P . | P . |

| All variables | ||

| Response to cytoreductive therapy | <.01 | <.01 |

| B symptoms at relapse | .06 | .03 |

| Excluding response | ||

| B symptoms at relapse | .01 | <.01 |

| Initial disease stage | NS | .12 |

Other variables entered into the analysis include: stage at initial diagnosis, B symptoms at initial diagnosis, initial treatment with radiotherapy alone, duration of remission (induction failure v ≤12 mo v >12 mo), stage at relapse, age at relapse, B symptoms at relapse, number of extra nodal disease sites at relapse, prior radiotherapy, relapse in site of prior radiotherapy and response to cytoreductive therapy (CR/MD v PR v NR). NS: P > .20.

Comparative analysis.Univariate analyses were performed on the combined group of high-dose and conventional salvage patients (Table 6). Treatment at relapse (high-dose therapy v conventional salvage therapy) was entered as an independent variable. A favorable response (CR or MD) to cytoreductive/salvage therapy and the absence of B symptoms at relapse were predictive of OS, FFP, and EFS. The use of high-dose therapy did not predict for overall survival, although it did predict for improved FFP and EFS, as did a longer duration of remission and no prior radiotherapy.

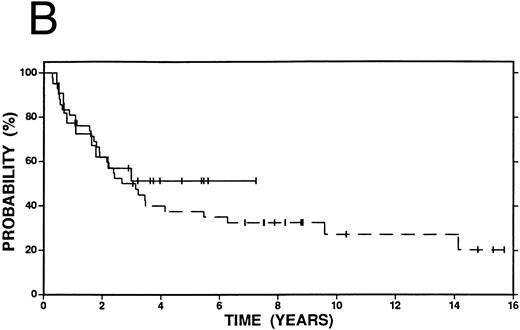

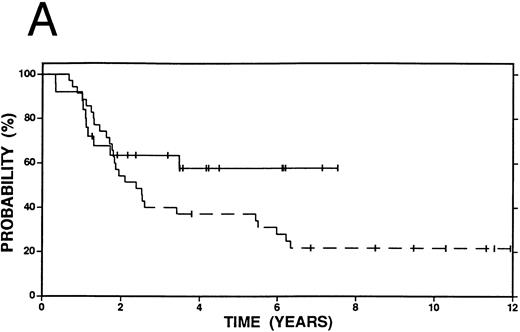

Survival in patients failing induction therapy and who subsequently received either high-dose therapy and autografting (solid line, n = 13) or conventional salvage therapy (n = 26, dashed line). (A) Overall survival. Log-rank P < .20. (B) Event-free survival. Log-rank P = .01.

Survival in patients failing induction therapy and who subsequently received either high-dose therapy and autografting (solid line, n = 13) or conventional salvage therapy (n = 26, dashed line). (A) Overall survival. Log-rank P < .20. (B) Event-free survival. Log-rank P = .01.

Univariate Analysis: All Patients

| . | OS . | EFS . |

|---|---|---|

| . | P . | P . |

| Limited initial stage | NS | NS |

| No B symptoms initially | NS | NS |

| Duration of remission >12 mo | NS | <.01 |

| No prior radiotherapy | NS | .04 |

| No relapse in irradiated site | NS | NS |

| No extranodal sites at relapse | .14 | NS |

| No B symptoms at relapse | <.01 | .02 |

| Limited stage at relapse | NS | NS |

| CR/MD to cytoreductive/salvage therapy | <.01 | <.01 |

| High-dose therapy at relapse | NS | <.01 |

| . | OS . | EFS . |

|---|---|---|

| . | P . | P . |

| Limited initial stage | NS | NS |

| No B symptoms initially | NS | NS |

| Duration of remission >12 mo | NS | <.01 |

| No prior radiotherapy | NS | .04 |

| No relapse in irradiated site | NS | NS |

| No extranodal sites at relapse | .14 | NS |

| No B symptoms at relapse | <.01 | .02 |

| Limited stage at relapse | NS | NS |

| CR/MD to cytoreductive/salvage therapy | <.01 | <.01 |

| High-dose therapy at relapse | NS | <.01 |

NS: P > .20.

Backward selection Cox regression was performed on the combined patient group with the same variables as in the univariate analyses (Table 7). Response to cytoreductive/salvage treatment and B symptoms at relapse were the most significant predictors of overall survival. High-dose therapy at relapse and a longer duration of remission, in addition to response to cytoreductive/salvage treatment were predictive of FFP and EFS. A second Cox regression analysis excluded the variable, which coded for response to cytoreductive/salvage treatment. In this model, high-dose therapy at relapse and the absence of B symptoms at relapse were independently predictive of longer overall survival. High-dose therapy at relapse, a longer duration of remission, the absence of B symptoms at relapse, and no prior exposure to radiotherapy were independent predictors of extended EFS and FFP.

Cox Regression Analysis: All Patients

| . | OS . | EFS . |

|---|---|---|

| . | P . | P . |

| All variables | ||

| Duration of remission | NS | <.01 |

| B symptoms at relapse | .04 | NS |

| Response to cytoreductive therapy | <.01 | <.01 |

| Treatment at relapse (HDT v CS) | NS | <.01 |

| Excluding response | ||

| Duration of remission | NS | <.01 |

| Prior radiotherapy | NS | .02 |

| B symptoms at relapse | <.01 | <.01 |

| Treatment at relapse (HDT v CS) | .04 | <.01 |

| . | OS . | EFS . |

|---|---|---|

| . | P . | P . |

| All variables | ||

| Duration of remission | NS | <.01 |

| B symptoms at relapse | .04 | NS |

| Response to cytoreductive therapy | <.01 | <.01 |

| Treatment at relapse (HDT v CS) | NS | <.01 |

| Excluding response | ||

| Duration of remission | NS | <.01 |

| Prior radiotherapy | NS | .02 |

| B symptoms at relapse | <.01 | <.01 |

| Treatment at relapse (HDT v CS) | .04 | <.01 |

Other variables entered into the analysis include: stage at initial diagnosis, B symptoms at initial diagnosis, stage at relapse, number of extra nodal disease sites at relapse, prior radiotherapy, relapse in site of prior radiotherapy. NS: P > .20.

Kaplan-Meier curves for OS and EFS comparing high-dose therapy and conventional salvage groups are shown in Fig 1A and B. The overall survival at 4 years was slightly greater in the high-dose therapy group (54% v 47%, P = .25). However, nearly twice as many patients were free from progressive Hodgkin's disease (62% v 32%, P < .01) or free from an adverse event (53% v 27%, P < .01) in the high-dose therapy group compared with the conventional salvage group.

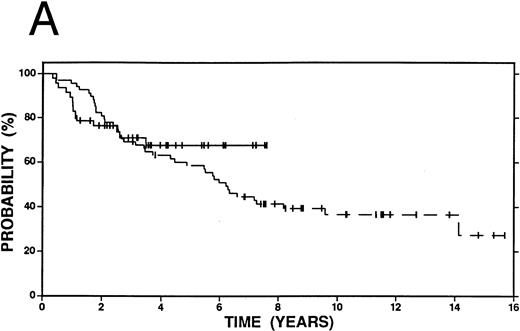

While Fig 1A and B compare all patients who received high-dose or conventional salvage therapy, Fig 5A and B show a comparison between the most favorable subset of patients: those who achieved a CR or MD to cytoreductive treatment or salvage therapy. Overall survival was similar at 4 years (68% v 63%, P = .25), although the advantage of high-dose therapy in FFP (71% v 49%, P = .06) and EFS (66% v 40%, P = .06) was maintained even in this favorable group of patients.

Survival among patients who achieved a complete response or minimal disease state prior to salvage therapy with high-dose therapy and autografting (n = 47, solid line) or with conventional salvage therapy (n = 68, dashed line). (A) Overall survival. Log-rank P < .20. (B) Event-free survival. Log-rank P = .06.

Survival among patients who achieved a complete response or minimal disease state prior to salvage therapy with high-dose therapy and autografting (n = 47, solid line) or with conventional salvage therapy (n = 68, dashed line). (A) Overall survival. Log-rank P < .20. (B) Event-free survival. Log-rank P = .06.

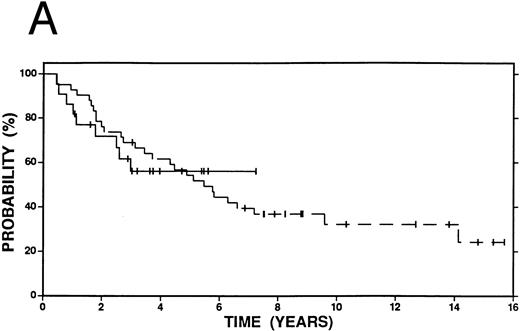

Among patients with a duration of remission >12 months, there was no statistically significant difference in OS, FFP, or EFS at 4 years between patients who received high-dose therapy and those who received conventional salvage treatment (Fig 2A and B). However, among patients with a shorter duration of remission (≤12 months), OS (58% v 38%, P = .15), FFP (58% v 19%, P < .01) and EFS (56% v 19%, P < .01) were improved among patients who received high-dose compared with conventional salvage therapy (Fig 3A and B). A similar advantage at 4 years was seen among patients who had failed induction therapy and were treated with high-dose therapy: OS (44% v 38%, P = .32), FFP (52% v 19%, P = .01), and EFS (52% v 19%, P = .01) (Fig 4A and B).

Survival in patients with an initial duration of remission 12 months or less treated at relapse with either high-dose therapy and autografting (solid line, n = 25) or conventional salvage therapy (n = 35, dashed line). (A) Overall survival. Log-rank P = .15. (B) Event-free survival. Log-rank P < .01.

Survival in patients with an initial duration of remission 12 months or less treated at relapse with either high-dose therapy and autografting (solid line, n = 25) or conventional salvage therapy (n = 35, dashed line). (A) Overall survival. Log-rank P = .15. (B) Event-free survival. Log-rank P < .01.

DISCUSSION

Conventional salvage treatment for recurrent or refractory Hodgkin's disease has generally been poor. Patients with long intervals between initial treatment and relapse may have complete response rates above 50%. However, even among this favorable group of patients, disease-free survival decreases to only 20% to 50% at 5 years.2 23 Patients who have less than a complete initial response or who relapse in less than a year have a considerably worse prognosis.

High-dose therapy with autografting has been used as salvage therapy for patients with refractory or relapsed Hodgkin's disease for more than 10 years. Results from these generally uncontrolled trials appear encouraging when compared with historical data.5-15 However, the studies contain heterogeneous groups of patients with different initial therapies, different numbers of relapses, and different high-dose preparatory regimens. Moreover, the patients who undergo high-dose therapy and autografting may be highly selected with predictably better outcomes.

Few randomized controlled trials have compared high-dose therapy with conventional salvage treatments. Linch et al24 compared high-dose BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan) chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow transplant (ABMT) to lower doses of BEAM without ABMT. Event-free survival was significantly better in the high-dose chemotherapy group. Overall survival was also higher in the ABMT group, but the difference had not reached statistical significance.

Lohri et al25 retrospectively analyzed a group of 71 patients treated at first relapse with a variety of methods. Sixteen patients received high-dose chemotherapy and ABMT at time of relapse. Sequential univariate analysis identified B symptoms at relapse, time to relapse of less than 1 year, and original stage IV disease as most predictive of poor survival. The presence of one negative risk factor was the major determinant of outcome irrespective of the type of salvage treatment. Patients with no risk factors did as well with irradiation or doxorubicin-based chemotherapy as with high-dose chemotherapy and ABMT.

The current study compares a group of patients treated with high-dose therapy and autografting with an historical group of patients treated at Stanford University before the availability of high-dose therapy. Only patients who had failed induction therapy or who were in first relapse and who received HDT were considered. The historical control group was chosen to match the general patient characteristics of the HDT group.

The outcome of the conventional salvage comparison group was similar to that reported in the literature. Only 27% of patients were free of an adverse event at 4 years, and 47% were alive at the time. Important prognostic variables for overall survival after relapse were fewer months of prior MOP(P) chemotherapy, longer duration of remission, absence of B symptoms at relapse, and greater percentage of optimal chemotherapy doses received at relapse. A favorable response at relapse was highly predictive of survival and event-free survival in the model that included this variable.

High-dose therapy was generally well tolerated and as effective as reported in other series. There were no cases of treatment-related leukemia or myelodysplasia and there were six cases of treatment-related mortality. Sixty percent of patients were free from progression at 4 years. Response to cytoreductive therapy was the singularly most important predictor of overall and event-free survival. B symptoms were the most important predictor in the model that excluded response. However, unlike results from Vancouver,26 the duration of remission did not independently predict for overall or event-free survival.

The Kaplan-Meier curves (Fig 1A and B) that compare the entire group of high-dose and conventional salvage patients show an advantage with high-dose therapy in event-free survival and freedom from progression. Overall survival was also improved, though the difference did not reached statistical significance. From this analysis, one might conclude that HDT is superior to conventional salvage treatments. However, comparing patient populations ignores differences in the distribution of important variables. When only the most favorable patients are compared (CR or MD to salvage/cytoreductive therapy or duration of remission longer than 1 year), then the differences between the two salvage treatments decrease (Figs 2 and 5). When one considers the subgroup of patients with the least favorable prognosis with conventional therapy (induction failure or short remission duration), both event-free survival and overall survival are considerably improved among the high-dose group (Figs 3 and 4). These data suggest that patients with the least impressive response to induction chemotherapy may benefit most from high-dose therapy, while those with responsive disease may still have improved outcomes with high-dose therapy, though the additional benefit may not be as great.

In addition to the univariate analyses described above, the current study used Cox regression analysis to account for differences in the distribution of variables between groups and to identify independently predictive variables. The type of salvage therapy (high-dose v conventional salvage) was considered as a separate variable in multivariate regression. The outcome of the analysis illustrates several interesting points. First, the sensitivity of disease as reflected by the response to salvage/cytoreductive therapy and the presence of B symptoms at relapse were the most significant predictors of overall survival, regardless of the type of salvage therapy. The use of high-dose therapy, in addition to a longer remission, were predictive of event-free survival and freedom from progression. Second, the analysis showed that other factors besides the type of salvage therapy were predictive of outcome after relapse.

The conclusions drawn from this study must be tempered with several caveats. The comparison conventional salvage group of patients cannot substitute for a concurrent randomized group of patients. The conventional salvage group consists of patients who were treated over a long period of time during which primary treatment patterns have changed. For example, the extended use of MOP(P) chemotherapy is much less frequent now than in the past, and the duration of primary treatment has shortened considerably.

Caution must also be exercised since advances in treatment can affect the effectiveness and safety of both high-dose therapy and what one might consider modern conventional salvage treatment. For example, mortality related to high-dose therapy and autografting has decreased even over the relatively brief period of use at SUMC. Growth factors may allow greater doses of conventional salvage therapy to be administered.

In conclusion, the use of high-dose therapy and autografting is but one of several independent and important factors. However, high-dose therapy and autografting offers improved outcomes even among those patients with the most favorable characteristics. The benefit of high-dose therapy is particularly pronounced among those with less favorable prognostic factors. Longer follow-up is necessary to see if the differences are maintained over time, and in particular, to appreciate the late effects of treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors gratefully acknowledge the work of the members of the Division of Bone Marrow Transplantation in the Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine.

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, Grant No. CA 49605 (Karl G. Blume), Marrow Grafting for Lymphoma, Project II: Bone Marrow Grafting for Leukemia and Lymphoma) and National Institutes of Health Grant No. CA 56060 to S.J.H., Clinical Investigations in Hodgkin's Disease. A.R.Y. is supported, in part, by the Lymphoma Research Foundation of America (Los Angeles, CA).

Address reprint requests to Sandra J. Horning, MD, 1000 Welch Rd, Suite 202, Palo Alto, CA 94305.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal