Abstract

Programmed cell death (or apoptosis) is a physiological process essential to the normal development and homeostatic maintenance of the immune system. The Fas/Apo-1 receptor plays a crucial role in the regulation of apoptosis, as demonstrated by lymphoproliferation in MRL-lpr/lpr mice and by the recently described autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) in humans, both of which are due to mutations in the Fas gene. We describe a novel family with ALPS in which three affected siblings carry two distinct missense mutations on both the Fas gene alleles and show lack of Fas-induced apoptosis. The children share common clinical features including splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy, but only one developed severe autoimmune manifestations. In all three siblings, we demonstrated the presence of anergic CD3+CD4−CD8− (double negative, [DN]) T cells; moreover, a chronic lymphocyte activation was found, as demonstrated by the presence of high levels of HLA-DR expression on peripheral CD3+ cells and by the presence of high levels of serum activation markers such as soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2R) and soluble CD30 (sCD30).

PROGRAMMED CELL DEATH (or apoptosis) is a key mechanism of cellular homeostasis in the immune system, both in the thymus (resulting in deletion of autoreactive thymocytes), and in the periphery, where activation-induced cell death (AICD) plays a crucial role in the extinction of the immune response to foreign antigens and in the peripheral deletion of autoreactive lymphoid cells.1-3

Fas/Apo-1 (CD95) and Fas ligand (FasL), two counter-receptors expressed on the surface of activated lymphocytes, have been recognized as functional molecules in AICD.4,5 Cross-linking of Fas with specific antibodies,6,7 with cells expressing Fas-ligand (FasL), or with purified soluble FasL8,9 leads to apoptosis, with appearance of characteristic cytoplasmic and nuclear condensation and DNA fragmentation. A characteristic motif (the so-called death domain) in the intracytoplasmic tail of Fas, sharing homology with a similar sequence of the closely related tumor necrosis factor-receptors (TNF-R), is involved in the apoptotic signal, as indicated by naturally occurring and artificially created Fas mutants.10,11 Murine models of defective Fas function include the MRL-lpr/lpr and the lprcg mice, both of which are characterized by massive lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly, with accumulation of a unique population of CD3+TCRAB+CD4−CD8− (referred to as double negative [DN], T cells) in the periphery.12,13 In addition, both MRL-lpr/lpr and lprcg mice show an increased occurrence of autoimmune manifestations, whose severity is highly influenced by the genetic background.14 15

Occurrence of lymphoproliferation in murine models of Fas defect is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait.12,13 More recently, human equivalents of the murine lpr/lpr phenotype have been reported in eight patients from seven unrelated pedigrees16,17; lack of apoptosis was observed in vitro, upon addition of agonistic antibodies to Fas. In all cases, the clinical features included early-onset splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy with accumulation of CD3+ DN T cells (mainly expressing the AB form of the T-cell receptor [TCR]); in addition, a variable degree of autoimmune manifestations were present. In all cases reported so far, patients had heterozygous mutations in the Fas gene, which in some cases led to production of dominant negative Fas mutants interfering with the function of wild-type Fas molecules. In two pedigrees (patients 2 and 3 from Rieux-Laucaut et al16 and family 3 from Fisher et al17 ), the investigators postulated a digenic disorder, because they found defective, but not abolished, Fas-induced apoptosis in the parent who did not carry mutations in the Fas gene. Based on these observations, the pattern of inheritance of the human Fas defect appears to differ from that reported in MRL-lpr/lpr mice.

We describe a novel family with autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) in which three affected siblings carry two distinct missense mutations in the Fas gene and show a lack of Fas-induced apoptosis. No clinical or immunological defect and no evidence of defective Fas function was identified in the parents, each of whom carried one of the two mutant alleles. Extensive family history failed to show other affected relatives. This is the first example of a human autosomal recessive ALPS due to single amino acid substitution in the Fas protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

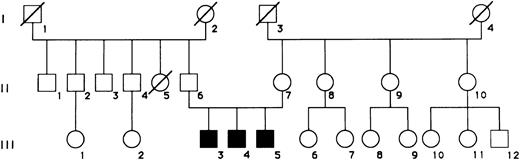

Case reports.A pedigree with three male siblings (III,3-5) with clinical features of ALPS is shown in Fig 1. As shown in Table 1, these children shared the clinical features of severe, early-onset splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy, as well as the presence of autoantibodies, which were associated with autoimmune hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia in patient N.F. One of the patients (M.F.) developed hypergammaglobulinemia, with increased IgG and IgA serum levels. The parents were unrelated and showed no clinical or immunological abnormalities, or had they ever developed adenopathy or splenomegaly in childhood. A detailed clinical history and physical examination was obtained in all relatives, and none of them appeared to have developed lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, or autoimmunity at any time in their life. Subject II,5 had died at 26 years of age of osteosarcoma; subject III,12 presents with mental and motor retardation as the result of perinatal asphyxia.

Pedigree of a family with ALPS. Patients III,3, III,4, and III,5 correspond to subjects SF, NF, and MF, respectively.

Pedigree of a family with ALPS. Patients III,3, III,4, and III,5 correspond to subjects SF, NF, and MF, respectively.

Patients' Features

| Features . | Patient M.F. . | Patient N.F. . | Patient S.F. . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 5 yr 11 mo | 13 yr 8 mo | 15 yr 4 mo |

| Splenomegaly | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| (age at onset) | 1 mo | 1 yr 6 mo | 1 yr |

| Lymphoadenopathy | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| IgG (g/L) | 41.8 | 12.0 | 13.6 |

| IgA (g/L) | 5.5 | 2.1 | 2.9 |

| IgM (g/L) | 1.4 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| Autoimmunity: | |||

| Clinical features | None | AHA, thrombocytopenia | None |

| Autoantibodies | ANA, APL | APL, APA | ANA, APL |

| Features . | Patient M.F. . | Patient N.F. . | Patient S.F. . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 5 yr 11 mo | 13 yr 8 mo | 15 yr 4 mo |

| Splenomegaly | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| (age at onset) | 1 mo | 1 yr 6 mo | 1 yr |

| Lymphoadenopathy | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| IgG (g/L) | 41.8 | 12.0 | 13.6 |

| IgA (g/L) | 5.5 | 2.1 | 2.9 |

| IgM (g/L) | 1.4 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| Autoimmunity: | |||

| Clinical features | None | AHA, thrombocytopenia | None |

| Autoantibodies | ANA, APL | APL, APA | ANA, APL |

Abbreviations: AHA, autoimmune hemolytic anemia; ANA, antinuclear antibody; APL, antiphospholipid antibody; APA, antiplatelet antibody.

Evaluation of autoimmunity.Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) were detected by indirect immunofluorescence using HEp-2 cells as substrate (Kallestad, Chaska, MN), and titers of at least 1:80 were considered positive. Anticardiolipin antibodies were measured in patients sera by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), following the method suggested by the International Standardization Workshop.18

Cell preparation.Mononuclear cells from the patient and from the parents were separated from the peripheral blood by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation and washed three times in RPMI-1640 (GIBCO Laboratoires, Grand Island, NY).

Depletion of CD4+ and CD8+ cells from peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) was obtained using negative selection with CD4− and CD8− conjugated magnetic beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway), as recommended by the manufacturer; less than 3% of negatively selected PBMC expressed CD4 and CD8 after this procedure, as assessed by immunofluorescence analysis. This population was enriched in CD3+CD4−CD8− cells (51%) and was, therefore, used in experiments of proliferation, CD40L expression, and T-cell receptor beta variable chain (TCRBV) mRNA analysis.

For the same analysis, CD4+ and CD8+ cells were further purified from PBMC by positive selection with CD4- and CD8-coated beads (Dynal): over 96% of positively selected cells were CD4+ or CD8+.

Cell cultures.All experiments were performed in complete medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), 1% glutamin and antibiotics. Proliferative responses were measured in triplicates of 200 μL containing 1 × 105 total or CD4/CD8-depleted PBMC using various combinations of the following stimulating agents: immobilized anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (MoAb), 200 ng/mL (OKT3; Ortho, Raritan, NJ), with or without interleukin-2 (IL-2), 20 U/mL (Biosource International, Camarillo, CA); phytohemoagglutinin (PHA), 1.2 μg/mL (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA); Staphylococcus aureus Enterotoxin B (SEB; 500 ng/mL; Serva Feinbiochemica, Heidelberg, Germany). After 72 hours of culture at 37°C, 5% CO2 , the cells were pulsed overnight with 1 μCi (3H)-thymidine and were harvested subsequently. Incorporated radioactivity was measured by liquid scintillation counting (Beckman, Fullerton, CA) and the results were expressed as mean cpm of triplicates ± standard error of mean (SEM).

Immunofluorescence.Evaluation of lymphocyte surface membrane expression was performed on heparinized whole blood samples with the following MoAbs: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated OKT3 (CD3), FITC-OKT4 (CD4), FITC-OKT8 (CD8), FITC-OKT11 (CD2), phycoerytrin (PE)-conjugated OKDR (HLA DR) from Ortho, FITC-TCR alpha/beta (TCRAB), PE-Leu 28 (CD28), PE-Leu11c (CD16), Leu-23 (CD69) from Becton Dickinson (Mountain View, CA), FITC-B4 (CD19) from Coulter Immunology (Hialeah, FL). For unconjugated MoAbs, an indirect immunofluorescence method was applied using a FITC-affinity–purified goat antimouse IgG antibody (Ortho).

For CD95 expression analysis, 2 × 105 PBMC were cultured in 96-well flat-bottomed microtiter plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) with PHA (1.2 μg/mL) in a final volume of 200 μL/w.

After activation for 72 hours, cells were harvested, washed two times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-5% FCS, and incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with a panel of different mouse monoclonals to human CD95: CH11 antibody (Medical and Biological Laboratories Co, Nagoya, Japan); DX2 antibody (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA); 7C11 antibody (from Robertson) and B.D29, B.E28, B.G27, B.G30, B.G34, B.K14, B.L25 antibodies (from Cattin/Wijdenes), provided through the 6th International Workshop and Conference on Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens. Cells were then washed twice in PBS-FCS and incubated with FITC-affinity–purified goat antimouse IgG antibody (Ortho).

For CD40 ligand (CD40L) and CD69 expression analysis, 2 × 105 CD4/CD8-depleted PBMC, or CD4+ plus CD8+ cells were cultured in 96-well flat-bottomed microtiter plates (Nunc) with PMA (5 ng/mL; Sigma, St Louis, MO) plus ionomycin (500 ng/mL; Sigma) in a final volume of 200 μL/w.

After activation for 16 hours, cells were harvested, washed two times with PBS-5% FCS, and incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C, respectively, with 50 μL of antihuman CD40L specific mouse MoAb (TRAP1, kindly provided by Dr R. Kroczek, Robert Koch Institute, Berlin, Germany); cells were then washed twice in PBS-FCS and incubated with FITC-affinity–purified goat antimouse IgG antibody (Ortho).

After two washes in PBS-FCS, samples were analyzed with a flow cytometer equipped with an argon-ion laser (488 nm; Cytoron Absolute; Ortho), using the ABS software. Gates were selected on lymphoid cells as determined by forward and right-angle scatter properties; dead cells were excluded by setting an appropriate threshold trigger on the low forward light scatter parameter, and nonspecific staining was assessed using FITC-conjugated nonimmune mouse IgG (Coulter). Data were acquired and stored in list mode. Fluorescence analysis was performed on a log scale.

Soluble activation markers determination.Serum levels of sIL-2R and sCD30 were evaluated with a commercial ELISA-kit (respectively, T Cell Diagnostics, Cambridge, MA and Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), as recommended by the manufacturer.

Apoptosis assay.For the apoptosis assay, after activation for 2 days with PHA (1.2 μg/mL) and 5 days with IL-2 (20 U/mL), PBMC (2 × 106/mL) were transferred to a 96-well culture plate coated with MoAb CH11 at the indicated concentration, or supplemented with dexamethasone 10−5 mol/L.

Cells were washed after 24 hours and the percentage of hypodiploid nuclei (less than 2N DNA content) was determined with a slight modification of the method of Nicoletti et al.19

Briefly, 1 × 106 lymphocytes were fixed in 1 mL of cold 70% ethanol at 4°C for 20 minutes. Cells were then washed, incubated at room temperature for 1 minute with RNase (0.5 mg/mL; Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), for 15 minutes with propidium iodide (100 μg/mL; Sigma), and immediately analyzed. The correct threshold was selected experimentally using the model system of apoptosis induced in murine thymocytes by 72 hours culture with dexamethasone 10−7 mol/L. Apoptotic cell nuclei, easily distinguishable from debris owing to the condensation of nuclear chromatin, emitted red fluorescence in the RD-FL channels 46-146. As there was no overlap between apoptotic nuclei and debris, the small percentage of residual low-fluorescence detritus (<1% in normal cells) was eliminated by gating at channel 45 of the red fluorescence scale. All measurements were performed with the same instrument setting.

The percent of hypodiploid cells at each CH11 concentration was calculated as follows: (% of hypodiploid cells from wells with MoAb − % of hypodiploid cells from wells without MoAb)/100 − % of hypodiploid cells from wells without MoAb.

Moreover, the percent of hypodiploid cells induced by dexamethasone was calculated as follows: (% of hypodiploid cells from wells with dexamethasone − % of hypodiploid cells from wells without dexamethasone)/100 − % of hypodiploid cells from wells with dexamethasone.

Preliminary experiments on healthy subjects failed to show significant differences in either Fas-mediated or dexamethasone-induced apoptosis between children and adults.

DNA extraction.High molecular weight DNA was isolated from proteinase-K–treated peripheral blood leukocytes by salting-out in mini scale, as previously described in detail.20 Briefly, erythrocytes were lysed by the addition of 2 mL red blood cell lysis buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.6; 5 mmol/L MgCl2 ; 10 mmol/L NaCl) to 1 mL EDTA blood; leukocytes were spun down (13,000 rpm for 1 minute); the pellet was washed once with H2O (13,000 rpm for 1 minute) and resuspended in 340 μL proteinase-K buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.6; 10 mmol/L EDTA, pH 8; 50 mmol/L NaCl), 30 μL 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 30 μL proteinase-K (20 mg/mL) and then incubated at 56°C for 30 minutes; after the addition of 200 μL saturated Na-acetate, the sample was shaken vigorously for 15 seconds; precipitated proteins were spun down (13,000 rpm, 5 minutes); 600 μL isopropyl alcohol was added to the supernatant; the precipitated DNA was washed once with 70% ethanol at room temperature, and finally dissolved in H2O.

Preparation of RNA, cDNA synthesis, and amplification of cDNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).Total RNA was prepared by the guanidinium thiocianate-phenol–chloroform method from PBMC of the patients. One microgram of RNA was used to synthesize the first strand of the FAS chain-specific complementary DNA (cDNA) using the RiboClone cDNA Synthesis System (Promega Corp, Madison, WI) and a Fas-specific primer ( 5′ CTA GAC CAA GCT TTG GAT TTC 3′). The cDNA reaction mixture was then subjected to enzymatic amplification using the following Fas forward and reverse primers (5′ ACG TGA TTC ATG TTG GGC ATC TGG ACC CTC CTA 3′; 5′ ACG TAA GCT TAC TAG TAA TGT CCT TGA GG 3′), which was designed to amplify the functional gene. The original sequences of these primers were modified respectively by adding at the 5′ end an EcoRI and HindIII restriction site. The PCR product is about 1,100 bp long. The amplification was performed for 35 cycles under the following conditions: denaturation at 93°C for 60 seconds, annealing at 52°C for 60 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 120 seconds. The last cycle extension was performed at 72°C for 10 minutes.

For TCR repertoire analysis, 1 μg of RNA from both CD4+ CD8+ and TCRAB+ CD4− CD8− lymphocyte subpopulation of the only child studied (M.F.) was also used to synthesize the first strand of the TCRB chain-specific cDNA using the RiboClone cDNA Synthesis System and a primer specific for TCRBC1 and TCRBC2 human genes (βcDNA: 5′ GGG CTG CTC CTT GAG GGG CTG CGG 3′). The cDNA was then subjected to enzymatic amplification using a second TCRBC primer (βAI: 5′ CCC ACT GTG CAC CTC CTT CC 3′) and a TCRBV degenerated primer (Vβd: 5′ T(GT)T(ACT) (CT)TGGTA(CT)(AC)(AG)(AT)CA 3′), which was designed to amplify TCRB chain rearrangements containing virtually all the known human TCRBV genes.21 The PCR products are about 430 bp long; they contain one half of the V region gene and extend through the V-D-J junction to the TCRBC region. The amplification was performed under the following conditions: 40 cycles of 93°C for 60 seconds, 52°C for 60 seconds, and 72°C for 60 seconds. The specificity of the total amplified products was analyzed using the previously described colorimetric method and biotynilated TCRBV-specific probes.22 The relative percentage of expression of each of the TCRBV segments analyzed was calculated by normalizing the optical density (OD) value of each individual TCRBV segment (OD[i]) with respect to the sum of the OD values of all 26 TCRBV chains.

Preparation of genomic DNA and amplification of target FAS sequences by PCR.Amplification of the genomic fragment encompassing the mutation in exon 9 was obtained with the following primers: F5′-CTGAAGTACTATAAAAGAGAAAT-3′; R5′-GTCATTCTTGATCTCATCTATTTTGGCT-3′, whereas the genomic region encompassing the mutation in exon 4 was amplified with these primers: F5′-TAACTAATAGTTTCCAAACTG-3′; R5′-TGTTTTAATCAGAGAAAGAC-3′. For PCR amplification, the following conditions were used: 30 cycles at 93°C for 30 seconds, 50°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 30 seconds, and 94°C for 30 seconds, 59°C for 60 seconds, 72°C for 60 seconds for mutation in the exon 4 and 9, respectively. The last cycle extension was performed at 72°C for 10 minutes.

The 169-bp segment surrounding the mutation in exon 4 was trimmed to 56 bp by digestion with HpaII to facilitate mutation detection. The same analysis was extended to 51 additional unrelated normal subjects.

Cloning and sequencing of the RT-PCR FAS product.The PCR product was ligated to a pCRII vector (TA Cloning Kit; Invitrogen Corp, San Diego, CA). Plasmids were grown in INVαF′ modified competent Escherichia coli cells in LB agar plates, and single plaques were picked up and expanded according to the manufacturer's instructions (TA Cloning Kit). To verify the presence of the correct insert, recombinant plaques were tested by PCR with the previously described primers. Positive plaques were selected, and plasmid DNA was purified using QIAwell 8 Plasmid Kit (Qiagen) and sequenced with an Automated Laser Fluorescent A.L.F. DNA Sequencer (Pharmacia LKB, Uppsala, Sweden) using the AutoRead Sequencing Kit (Pharmacia). In the case of FAS cDNA clones, both universal and reverse primers were used.

RESULTS

Lymphocyte surface marker analysis.Immunophenotype of the PBL (Table 2) showed that all three siblings had an expansion of CD3+CD4−CD8− cells. Among CD4−CD8− T cells, a sizeable proportion was represented by TCRAB+ cells, a subset that is usually negligible in normal controls. In addition, all CD3+ lymphocytes were also CD2+ and a substantial proportion of them expressed the activation marker DR. Finally, an increased proportion of CD28− cells were found both among CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes. The distribution of NK (CD16+) and B (CD19+) lymphocytes did not differ from normal controls.

Main Immunological Features

| Surface Markers . | Patient M.F. . | Patient N.F. . | Patient S.F. . | Mother . | Father . | Normal Values (mean ± SD) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunophenotypical analysis (%) | ||||||

| CD2 | 84 | 91 | 84 | ND | ND | 80 ± 6 |

| CD3 | 73 | 88 | 80 | 81 | 75 | 71 ± 7 |

| CD4 | 13 | 28 | 30 | 45 | 57 | 40 ± 7 |

| CD8 | 42 | 37 | 26 | 35 | 16 | 25 ± 5 |

| CD16 | 9 | 6 | 7 | ND | ND | 11 ± 5 |

| CD19 | 13 | 11 | 12 | ND | ND | 18 ± 6 |

| HLA-DR | 41 | 23 | 25 | ND | ND | 20 ± 8 |

| CD4− CD8− among CD3+ | 30 | 21 | 26 | 2 | 3 | <5 |

| TCRAB+ among CD4− CD8− | 41 | 45 | 37 | <1 | <1 | <3 |

| HLA-DR+ among CD3+ | 33 | 19 | 18 | ND | ND | <10 |

| CD2+ among CD3+ | 97 | 98 | 95 | ND | ND | >95 |

| CD28− among CD4+ | 12 | 15 | 3 | 3 | 3 | <5 |

| CD28− among CD8+ CD3+ | 76 | 68 | 57 | 40 | 44 | 41 ± 14 |

| Surface Markers . | Patient M.F. . | Patient N.F. . | Patient S.F. . | Mother . | Father . | Normal Values (mean ± SD) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunophenotypical analysis (%) | ||||||

| CD2 | 84 | 91 | 84 | ND | ND | 80 ± 6 |

| CD3 | 73 | 88 | 80 | 81 | 75 | 71 ± 7 |

| CD4 | 13 | 28 | 30 | 45 | 57 | 40 ± 7 |

| CD8 | 42 | 37 | 26 | 35 | 16 | 25 ± 5 |

| CD16 | 9 | 6 | 7 | ND | ND | 11 ± 5 |

| CD19 | 13 | 11 | 12 | ND | ND | 18 ± 6 |

| HLA-DR | 41 | 23 | 25 | ND | ND | 20 ± 8 |

| CD4− CD8− among CD3+ | 30 | 21 | 26 | 2 | 3 | <5 |

| TCRAB+ among CD4− CD8− | 41 | 45 | 37 | <1 | <1 | <3 |

| HLA-DR+ among CD3+ | 33 | 19 | 18 | ND | ND | <10 |

| CD2+ among CD3+ | 97 | 98 | 95 | ND | ND | >95 |

| CD28− among CD4+ | 12 | 15 | 3 | 3 | 3 | <5 |

| CD28− among CD8+ CD3+ | 76 | 68 | 57 | 40 | 44 | 41 ± 14 |

| Patient M.F. (PBMC) | Patient M.F. (CD4− CD8− PBMC) | Healthy control (PBMC) | |

| Proliferative response | 190 ± 9 | 800 ± 95 | 2,200 ± 140 |

| Medium | |||

| PHA (1.2 μg/mL) | 35,550 ± 1,050 | 4,100 ± 35 | 51,500 ± 3,200 |

| CD3 (200 ng/mL) | 46,500 ± 270 | 2,000 ± 12 | 61,550 ± 1,600 |

| CD3 (200 ng/mL) + IL2 (20 U/mL) | 64,050 ± 680 | 7,350 ± 7 | 74,600 ± 920 |

| SEB (500 ng/mL) | 30,150 ± 920 | 1,600 ± 52 | 57,700 ± 920 |

| Patient M.F. (PBMC) | Patient M.F. (CD4− CD8− PBMC) | Healthy control (PBMC) | |

| Proliferative response | 190 ± 9 | 800 ± 95 | 2,200 ± 140 |

| Medium | |||

| PHA (1.2 μg/mL) | 35,550 ± 1,050 | 4,100 ± 35 | 51,500 ± 3,200 |

| CD3 (200 ng/mL) | 46,500 ± 270 | 2,000 ± 12 | 61,550 ± 1,600 |

| CD3 (200 ng/mL) + IL2 (20 U/mL) | 64,050 ± 680 | 7,350 ± 7 | 74,600 ± 920 |

| SEB (500 ng/mL) | 30,150 ± 920 | 1,600 ± 52 | 57,700 ± 920 |

Proliferation studies of M.F. patients' total and CD3+ CD4− CD8− enriched PBMC. Data are expressed as the mean cpm ± SEM of a triplicate culture. Similar results were obtained for patients N.F. and S.F. (data not shown).

Abbreviation: ND, not determined.

On the contrary, no immunophenotypical abnormalities (ie, presence of “double negative” cells or expansion of CD3+CD28− cells) were found on PBL of parents (Table 2).

Serum levels of soluble activation markers.In keeping with the demonstration of an increased proportion of activated (HLA-DR+) peripheral blood T lymphocytes, increased levels of serum sIL-2R were found in the patients (M.F.: 7,155 U/mL; N.F.: 1,989 U/mL; S.F.: 2,154 U/mL), as opposed to the parents (father: 803 U/mL; mother: 391 U/mL) and normal controls (mean ± SD: 526 ± 103 U/mL; n = 8). Similar results were obtained when serum levels of sCD30 were analyzed: in fact, higher levels were found in the patients (M.F.: 251 U/mL; N.F.: 59 U/mL; S.F.: 37 U/mL), as compared with the parents (father: 11 U/mL; mother: 17 U/mL) and normal controls (mean ± SD: 11 ± 9 U/mL; n = 8).

Immunological features of “double negative” T cells.Analysis of in vitro lymphocyte proliferation showed that PBMC from all three siblings mounted a normal proliferation to various stimuli (Table 2). In contrast, the enriched CD3+CD4−CD8− population were unresponsive to PHA, anti-CD3, and SEB. Addition of exogenous IL-2 slightly increased the proliferative capacity in response to CD3.

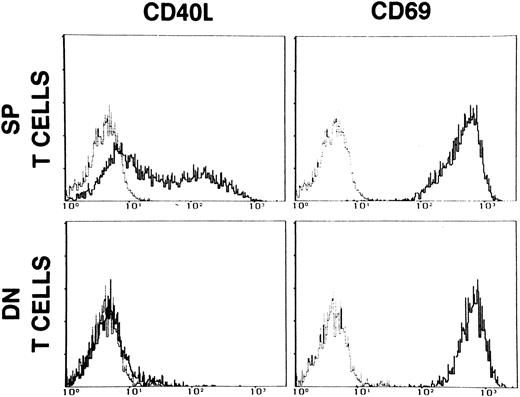

As shown in Fig 2, stimulation of DN T cells with optimal doses of PMA and ionomycin failed to induce CD40L, but resulted in normal expression of the activation marker CD69.

Expression of CD40L and CD69 on single positive (SP) T cells and on CD3+CD4−CD8− (DN) enriched PBMC of patient M.F. The cells were activated with PMA (5 ng/mL) + ionomycin (500 ng/mL) for 16 hours. Dashed lines represent the fluorescence of cells stained with nonimmune mouse IgG. Data are presented as relative log fluorescence intensity.

Expression of CD40L and CD69 on single positive (SP) T cells and on CD3+CD4−CD8− (DN) enriched PBMC of patient M.F. The cells were activated with PMA (5 ng/mL) + ionomycin (500 ng/mL) for 16 hours. Dashed lines represent the fluorescence of cells stained with nonimmune mouse IgG. Data are presented as relative log fluorescence intensity.

We performed analysis of the TCRBV repertoire of DN versus SP T cells in the affected sibling M.F., who showed the most prominent signs of lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly. No bias in the usage of the TCRBV rearrangements was identified in any cell subpopulation, arguing against preferential expansion of T-cell clones in response to specific antigens (data not shown).

Functional analysis of Fas-induced apoptosis.The demonstration of an expanded subset of DN T cells that were anergic to common in vitro stimuli prompted us to investigate the possibility of a Fas defect in the family.

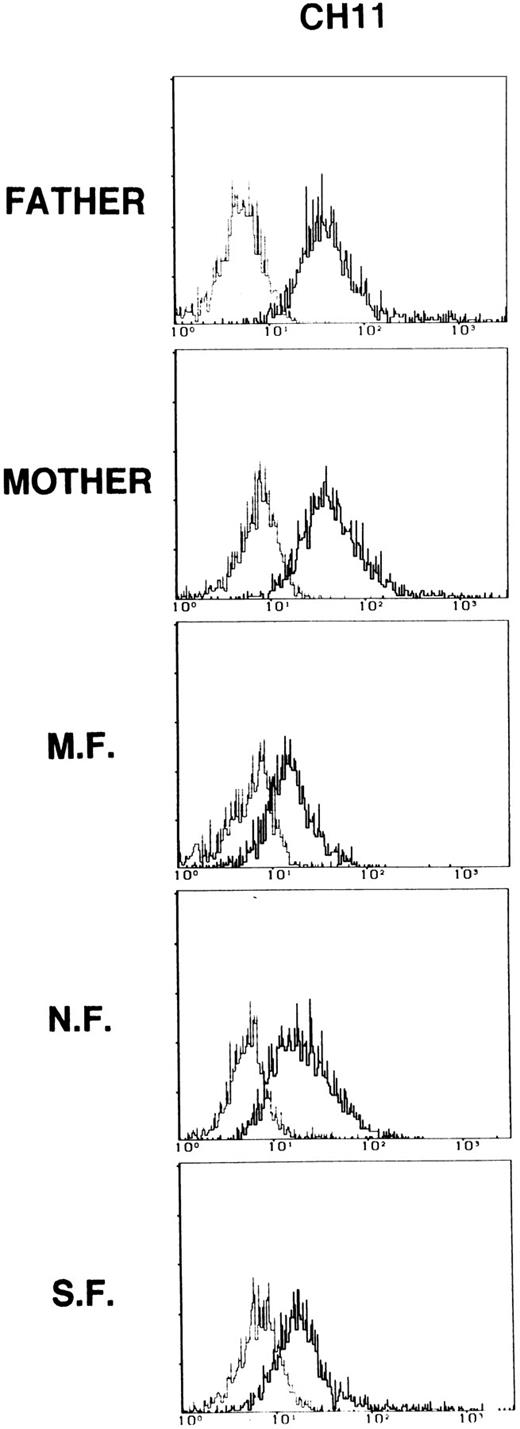

As shown in Fig 3 for monoclonal CH11, upon in vitro stimulation with PHA, PBMC from patients expressed the Fas molecule at the cell surface, but the intensity of staining was consistently slightly reduced as compared with the parents. Fas expression in activated PBMC from both parents was comparable to that observed in controls (data not shown). Similar results were produced with all anti-CD95 MoAb tested (data not shown).

CD95 expression on PBMC from patients and their parents. Cells were activated with PHA (1.2 μg/mL) for 72 hours. Dashed lines represent the fluorescence of cells stained with nonimmune mouse IgG. Data are presented as relative log fluorescence intensity. Data are representative of two independent determinations.

CD95 expression on PBMC from patients and their parents. Cells were activated with PHA (1.2 μg/mL) for 72 hours. Dashed lines represent the fluorescence of cells stained with nonimmune mouse IgG. Data are presented as relative log fluorescence intensity. Data are representative of two independent determinations.

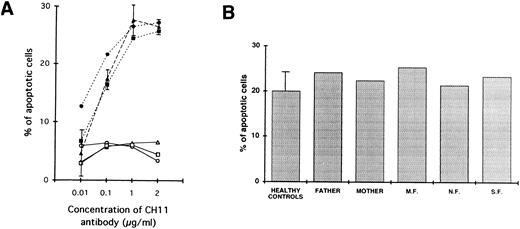

In addition, defective apoptosis through cross-linking of the Fas antigen was demonstrated in the affected siblings. In fact, as shown in Fig 4A, where the lymphocytes were stimulated with PHA for 2 days and IL-2 for 5 days, addition of various concentrations of CH11 antibody (which is known to deliver death signals through cross-linking of the Fas antigen) failed to result in AICD in the three siblings. In contrast, under the same conditions, a comparable apoptosis was described in the two parents and in a series of normal controls.

(A) Defective Fas-mediated apoptosis of patients' lymphocytes (○, M.F.; □, N.F.; ▵, S.F.) as compared with normal induction of apoptosis on lymphocytes from parents (•, father; ▪, mother) and five healthy controls (▴). Cells were activated with PHA (1.2 μg/mL) for 2 days and IL-2 (20 U/mL) for 5 days and then incubated for 24 hours with or without various concentrations of an anti-Fas antibody known to deliver an apoptotic signal (CH11). The percentage of apoptotic cells as a function of the CH11 antibody concentration is shown. For healthy controls, data are expressed as mean ± 1 SD. One representative experiment of three is shown. (B) Normal dexamethasone-induced apoptosis of lymphocytes from all affected siblings as compared with their parents and three healthy controls. Cells were activated with PHA (1.2 μg/mL) for 2 days and IL-2 (20 U/mL) for 5 days and then incubated for 24 hours with or without dexamethasone 10-5 mol/L. The percentage of apoptotic cells is shown.

(A) Defective Fas-mediated apoptosis of patients' lymphocytes (○, M.F.; □, N.F.; ▵, S.F.) as compared with normal induction of apoptosis on lymphocytes from parents (•, father; ▪, mother) and five healthy controls (▴). Cells were activated with PHA (1.2 μg/mL) for 2 days and IL-2 (20 U/mL) for 5 days and then incubated for 24 hours with or without various concentrations of an anti-Fas antibody known to deliver an apoptotic signal (CH11). The percentage of apoptotic cells as a function of the CH11 antibody concentration is shown. For healthy controls, data are expressed as mean ± 1 SD. One representative experiment of three is shown. (B) Normal dexamethasone-induced apoptosis of lymphocytes from all affected siblings as compared with their parents and three healthy controls. Cells were activated with PHA (1.2 μg/mL) for 2 days and IL-2 (20 U/mL) for 5 days and then incubated for 24 hours with or without dexamethasone 10-5 mol/L. The percentage of apoptotic cells is shown.

Finally, as shown in Fig 4B, the lymphocytes from all patients demonstrated intact apoptotic response when stimulated with dexamethasone, thus indicating that the cells of the patients were not intrinsically resistant to AICD.

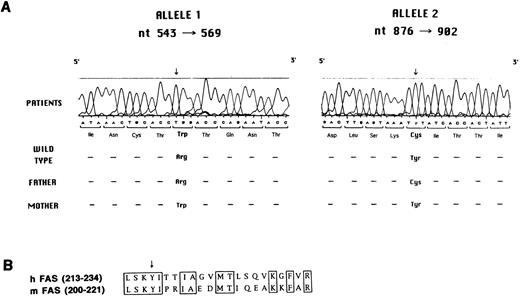

Molecular analysis of Fas defect.Search for mutations in the Fas gene was accomplished by reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR, cloning, and sequencing. As shown in Fig 5A, all three siblings were found to carry two distinct mutations, each of which was inherited from one of the parents.

(A) Mutation analysis in the Fas gene. Sequence analysis performed with the Automated Laser Fluorescent A.L.F. DNA Sequencer on amplified genomic fragments encompassing nt 543-569 and nt 876-902 of the Fas cDNA is shown. (B) Sequence of human and murine Fas cDNA at the N-terminus of the death domain. The conserved amino acids are boxed. The arrow indicates the tyrosine that is mutated to cysteine in the three affected siblings and in their father.

(A) Mutation analysis in the Fas gene. Sequence analysis performed with the Automated Laser Fluorescent A.L.F. DNA Sequencer on amplified genomic fragments encompassing nt 543-569 and nt 876-902 of the Fas cDNA is shown. (B) Sequence of human and murine Fas cDNA at the N-terminus of the death domain. The conserved amino acids are boxed. The arrow indicates the tyrosine that is mutated to cysteine in the three affected siblings and in their father.

In particular, the maternally-derived mutated allele carried a C to T mutation at nt 555, as compared with the wild-type cDNA sequence,23-25 which results in a tryptophane for arginine substitution at codon 105 in the second cystein-rich–homology (CRH) domain at the extracellular side of the protein. This mutation was confirmed at the genomic level by restriction analysis. In fact, the C to T mutation abolishes a restriction site for the HpaII enzyme. Genomic DNA amplification in the region encompassing nt −30 of intron three and nt +30 of intron four, followed by digestion with HpaII, generates two fragments of 113 and 56 bp. As expected, both in the patients and in their mother, an aberrant band of 169 bp was identified, in addition to the wild-type fragments of 113 and 56 bp, thus confirming heterozygosity for the mutation (data not shown). A similar analysis was applied to 51 normal individuals, none of whom showed the aberrant 169-bp band, thus also ruling out the possibility that the C to T change at nt 555 represents a polymorphism (data not shown).

The paternally derived mutant allele caused an A to G substitution at nt 889, resulting in a tyrosine to cysteine mutation at codon 216 at the N-terminus of the death domain in the intracytoplasmic region of the molecule. This mutation falls in a region conserved between human and murine Fas proteins (Fig 5B).

DISCUSSION

We have reported a novel family with ALPS due to mutations in the Fas gene resulting in lack of Fas-induced apoptosis despite preservation of Fas molecule expression. All three affected siblings inherited one mutated Fas allele from each heterozygous parent. Neither parent showed any immunological abnormalities (including Fas-mediated apoptosis), nor did they ever develop clinical signs of the disease; furthermore, extensive family history failed to show adenopathy, splenomegaly, or autoimmunity in any other relatives. Based on these findings, a typical autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance can be argued. This is similar to what was observed in MRL-lpr/lpr mice, but contrasts with most ALPS families due to Fas defects so far reported in humans, in which occurrence of a pathological phenotype, despite heterozygosity for Fas mutations, was explained by a dominant negative effect,17 or possibly by a digenic inheritance, with concurrent effect of a yet undefined apoptosis defect inherited from the parent with no mutations in the Fas gene.

In the present family, simultaneous occurrence of missense mutations on both Fas gene alleles was reported to result in defective apoptosis and aberrant clinical features. The maternally-inherited mutation resulted in the substitution of neutral tryptophane for the cationic arginine on the extracellular side of the protein, in the CRH2 domain. Although none of the reported Fas-gene polymorphisms lead to amino acid substitution,26 the possibility that this nonconservative amino acid change represents a polymorphism was ruled out, as no evidence for the same nucleotide substitution was obtained by PCR and restriction analysis in 51 normal subjects. For the paternally-derived mutation, although tyrosine 216 lies N-terminal to the Fas death domain, and its mutation to cysteine should not, therefore, directly affect the function of this motif, it is conserved in the murine homologue,24 27 suggesting structural or functional constraints. None of the two mutations alone substantially affects Fas expression or function, since heterozygous parents were comparable to controls. It is conceivable that depending on the severity of Fas gene mutations, Fas defect may follow a single autosomal recessive inheritance (as in the present case) or result from a dominant-negative effect, particularly when expression of mutant Fas protein strongly interferes with either Fas trimer expression or function.

Although little data are available on the CD95 epitopes recognized by the MoAbs used in this study, the demonstration that a reduced expression of CD95 was consistently observed in the three affected siblings with all CD95 monoclonals, is in favor of a reduced density of CD95 molecules at the cell surface rather than of a single conformational change.

Analysis of the clinical and immunological phenotype in the three affected siblings showed common features (including splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy), but a remarkably different degree of severity. Despite the same Fas defect in the three affected children, heterogeneity of the clinical phenotype is likely to result from the effect of the genetic background, as already reported for other families with Fas defect, and also suggested by analysis of different mice strains harboring the lpr/lpr mutation.14,15,28 Indeed, the demonstration in mice that the lpr/lpr mutation results in lymphoproliferation, while autoimmunity is strongly influenced by the genetic background,14 15 is in keeping with our observation that splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy were consistent in all affected children, while only one of them developed overt autoimmune symptoms. Therefore, it seems that impairment of Fas-induced apoptosis primarily results in inappropriate accumulation of lymphocytes, which in the presence of suitable genetic factors, may associate with autoimmunity.

On the other hand, as reported for MRL-lpr/lpr mice,29 we found no evidence for a restricted T-cell repertoire either in the unseparated SP and in the expanded DN T cells, suggesting that lymphoproliferation results from polyclonal accumulation of activated T cells.

The inability to extinguish immune reactions to exogenous and, possibly, autologous antigens in the periphery in ALPS, is accompanied by chronic lymphocyte activation. In fact, a substantial proportion of CD3+ cells coexpressed the HLA-DR activation antigen in all three affected children; in addition, elevated serum levels of sIL-2R and sCD30 were also found.

It is well recognized that to elicit effector mechanisms of response following T-cell activation, a second signal is required, in addition to engagement of the CD3/TCR complex.30,31 Accessory signals on the T-cell surface include, among others, the costimulatory molecules CD4, CD8, and CD28.32,33 It has been postulated that the aberrant accumulation of CD3+CD4−CD8− cells in MRL-lpr/lpr mice and in patients with Fas defect may result from downregulation of the expression of CD4 or CD8 molecules,34-37 as an attempt to anergize the otherwise chronically activated T cells. We have confirmed previous observations that the expanded DN T cells in MRL-lpr/lpr mice and in patients with Fas defect are unable to proliferate in response to a variety of activating stimuli.38-40 However, in keeping with previous observations,41 42 the impaired proliferation does not result from a global inability to transduce activation signals, since normal expression of the early activation antigen CD69 was observed.

Finally, we have demonstrated an increased proportion of CD28− cells among SP CD4 or CD8 T lymphocytes. Because CD28 costimulation is known to enhance expression of Bcl-xL ,43 and thus contribute to prolonged T-cell survival, downregulation of CD28 expression in SP T cells from patients with Fas defect may represent an additional mechanism for homeostatic control of terminally differentiated T cells that may not undergo Fas-mediated apoptosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr Angelo Manfredi for the generous gift of CH11 antibody, Dr Silvia Giliani for technical advice, and Dr Daniele Primi for critical review of the manuscript.

Supported in part by Telethon (Rome, Italy) Grant No. A.42 to L.D.N.

Address reprint requests to Duilio Brugnoni, MD, Servizio di Immunologia Clinica, Spedali Civili, 25123 Brescia, Italy.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal