Abstract

Thrombopoietin (TPO), the ligand for the receptor proto-oncogene c-Mpl, has been cloned and shown to be the critical regulator of proliferation and differentiation of megakaryocytic lineage. Initially, TPO was not considered to have the activity on hematopoietic lineages other than megakaryocytes. Recently, however, TPO was reported to enhance the in vitro erythroid colony formation from human bone marrow (BM) CD34+ progenitors or from mouse BM cells in combination with other cytokines. We examined the effects of TPO on the colony formation of hematopoietic progenitors in mouse yolk sac. TPO remarkably enhanced proliferation and differentiation of erythroid-lineage cells in the presence of erythropoietin (Epo). This effect was observed even in the absence of Epo. Compared with adult BM, yolk sac turned out to have relatively abundant erythroid and erythro-megakaryocytic progenitors, which responded to TPO and Epo stimulation. TPO similarly stimulated erythroid colony formation from in vitro differentiation-induced mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells whose hematopoietic differentiation status was similar to that of yolk sac. These findings help to understand the biology of hematopoietic progenitors of the early phase of hematopoiesis. Yolk sac cells or in vitro differentiation-induced ES cells would be good sources to analyze the TPO function on erythropoiesis.

THE PROTO-ONCOGENE c-Mpl is a novel member of the cytokine receptor superfamily, a family characterized by a common structural design of the extracellular domain including four conserved C residues in the N-terminal portion and a WSXWS motif close to the transmembrane domain.1-3 The c-Mpl possesses extensive homologies with the receptors for erythropoietin (Epo), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF ), and interleukin-3 (IL-3).1-3 Expression of c-mpl is restricted to spleen, bone marrow (BM), or fetal liver in mice and to megakaryocytes, platelets and CD34+ cells in humans.4 Antisense oligonucleotide to c-mpl selectively inhibited magakaryocytes colony formation in culture without affecting erythroid or myeloid colony formation.4 Moreover, c-mpl–deficient mice had a remarkable decrease in their number of platelets and megakaryocytes but had normal amounts of other hematopoietic cell types.5 These studies clearly show that c-Mpl plays a functional role in hematopoiesis, in particular, megakaryocytopoiesis.

Recently, several groups successfully purified and cloned the ligand for the c-Mpl receptor and showed that the Mpl ligand has high similarity with Epo in their nucleotide and amino acid sequences.6-11 Mpl ligand supports the proliferation of megakaryocytic progenitors and their differentiation into large polyploid, platelet-producing megakaryocytes.6,7,10,12-17 Mpl ligand levels in serum are inversely related to platelet count, and the administration of the cytokine profoundly drives platelet production in normal animals.10,14,18,19 These observations indicate that Mpl ligand is identical to thrombopoietin (TPO), the critical regulator of thrombopoiesis.15

TPO by itself can stimulate proliferation and differentiation from immature hematopoietic cells to magakaryocytes and fully matured platelets.7,12-17,20 Growth factor requirement of erythrocyte production is different from that of megakaryocyte/platelet production, ie, early erythroid progenitors and late erythroid progenitors require different factors for erythroid proliferation and differentiation. IL-3, granulocyte macrophage-CSF (GM-CSF ), stem cell factor (SCF/c-kit ligand), and IL-9 have been shown to expand early erythroid progenitors.21-25 Epo, which promotes the terminal differentiation of red blood cells, is the critical regulator of late erythroid progenitors.26 27

There is much evidence that points to a common nature of the erythroid and the megakaryocyte lineages. For example, erythroleukemic cell lines express markers of megakaryocytic differentiation,28,29 and megakaryocytic cell lines express markers of erythroid differentiation reciprocally.30 The cells of these two lineages share a number of common surface markers and transcription factors.31-33 Several groups have shown that Epo augments the effects of TPO on megakaryocyte formation in vitro.34-36 Furthermore, the results of three studies about the roles of TPO on erythroid cell proliferation were reported. (1) In vivo administration of TPO to mice expanded erythroid progenitors in the BM37; (2) in c-mpl–deficient mice, total hematopoietic progenitor cell numbers were reduced in multipotential, blast cell, and committed progenitors of multiple lineages including the erythroid lineage38; and (3) TPO enhanced erythroid burst formation from human CD34+ BM and cord blood cells in the presence of Epo.39 Here, we report that, in contrast to BM cells and fetal liver cells, TPO induced proliferation and differentiation of erythroid-lineage cells from untreated and unfractionated yolk sac cells in the presence or the absence of Epo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and tissues.Day-9.5 postcoitus, day-12.5 postcoitus, and normal adult C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Japan SLC Inc (Shizuoka, Japan). To obtain yolk sac cells and fetal liver cells, pregnant mice at day 10.5 postcoitus and day 13.5 postcoitus, respectively, were killed by cervical dislocation. Embryos were removed and placed in α-minimal essential medium (α-MEM; Life Technologies, Inc, Gaithersburg, MD) with 2% fetal calf serum (FCS; Summit, Ft Collins, CO). Yolk sac cells were obtained essentially as previously reported.40 A solution of 0.1% collagenase (Sigma, St Louis, MO) in Ca2+-, Mg2+-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 20% FCS was prepared just before use. Three yolk sacs were placed in 5 mL of the collagenase solution in a 50-mL tube. The solution was then incubated at 37°C for 3 to 4 hours with shaking at 15-minute intervals. After the incubation, the solution was passed with metal mesh and nylon mesh subsequently. These were washed twice with α-MEM supplemented with 20% FCS and then suspended in α-MEM as final suspension. The majority of the cells obtained were present as single cells. Fetal liver cells were homogenized with glass homogenizer, passed through metal and nylon meshes, and washed once with α-MEM supplemented with 20% FCS. Adult BM cells were flushed from the femur, and single cells were obtained by serial passage of hypodermic needles.

Methylcellulose cultures.Cells were mixed in a culture medium consisting of α-MEM plus 30% FCS (Summit), 0.8% methycellulose (Sigma), 1% deionized bovine serum albumin (Sigma), and 10−4 mol/L 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma) with various cytokines. One milliliter of the final methylcellulose mixture was plated in a 35-mm suspension-culture dish (Corning, Corning, NY), and the culture was incubated for 7 days in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 to develop colonies. In the experiment of “delayed addition,” colonies were examined 5 days after the delayed addition. Colonies containing more than 50 hemoglobinized cells were counted as the erythroid colonies. Megakaryocyte-containing cultures were counted as previously described.14 A total of 2 U/mL of recombinant human Epo, 10 ng/mL of recombinant human TPO (Kirin Brewery Co, Ltd, Maebashi, Japan), and 100 U/mL of mouse IL-3 (obtained from BMG-IL3 X63 cells41 ) were used as final concentrations. Antihuman TPO-blocking antibody42 was kindly provided by Kirin Brewery Co, Ltd. In the delayed addition experiments, 100 mL of the medium containing the cytokine(s) was added as the final concentration reached that described above.

In vitro differentiation of embryonic stem (ES) cells.The OP9 stromal cell line was maintained in α-MEM supplemented with 20% FCS and standard antibiotics.43,44 D3 mouse ES cells were maintained on embryonic fibroblast feeder cells in the presence of a saturated dose of leukemia-inhibitory factor.45,46 Differentiation induction was performed as described previously.44 47 D3 ES cells were transferred onto confluent OP9 stromal cells in 6-well plates at the cell density of 104/well. Culture media for the differentiation induction were the same as for the maintenance of OP9 cells. The induced cells were trypsinized at day 5, and 105 cells per well were transferred onto fresh OP9 cells. One day later, the cells, other than adherent OP9 cells, were harvested by gentle pipetting. Those cells were used for the methylcellulose culture as described above.

RESULTS

Enhancement of proliferation and differentiation of erythroid progenitors in mouse yolk sac by TPO.Day-10.5 yolk sac cells, day-13.5 fetal liver cells, and adult BM cells of C57BL/6 mice were cultured in methylcellulose semisolid culture media supplemented with Epo, TPO, or both. TPO augmented in vitro erythropoiesis of yolk sac cells significantly (Table 1). In the presence of Epo, TPO increased the number of the colonies containing erythroid cells from 31 ± 4 to 111 ± 6 (P < .0001 by Student's t-test). In addition, TPO induced erythroid cell proliferation and differentiation significantly even in the absence of Epo (from 0 ± 0 to 14 ± 2; P < .01 by Student's t-test). Meanwhile, Epo significantly enhanced megakaryocyte containing colony formation of yolk sac, fetal liver, and BM cells in the presence of TPO. In the absence of TPO, Epo enhanced megakaryocyte containing colony formation of yolk sac and fetal liver cells.

Colony Formation From Yolk Sac, Fetal Liver, and Adult BM Cells

| Factors . | No. of Colonies . | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Yolk Sac . | Fetal Liver . | BM . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||||||

| . | E + Meg . | E . | Meg . | Others . | E + Meg . | E . | Meg . | Others . | E + Meg . | E . | Meg . | Others . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| None | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 18 ± 3 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 12 ± 3 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 9 ± 1 | |||||||||

| EPO | 2 ± 1 | 30 ± 5 | 2 ± 1 | 21 ± 2 | 11 ± 1 | 27 ± 2 | 5 ± 1 | 9 ± 4 | 0 ± 0 | 21 ± 3 | 0 ± 0 | 10 ± 1 | |||||||||

| TPO | 6 ± 2 | 5 ± 1 | 73 ± 5 | 21 ± 2 | 2 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | 54 ± 5 | 10 ± 2 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 30 ± 1 | 10 ± 1 | |||||||||

| EPO + TPO | 61 ± 3 | 49 ± 4 | 68 ± 7 | 20 ± 3 | 24 ± 2 | 18 ± 1 | 69 ± 6 | 16 ± 2 | 3 ± 1 | 18 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 | 11 ± 2 | |||||||||

| IL-3 + EPO + TPO | 123 ± 7 | 43 ± 5 | 48 ± 5 | 57 ± 9 | 40 ± 2 | 25 ± 6 | 91 ± 1 | 98 ± 1 | 42 ± 4 | 19 ± 2 | 66 ± 9 | 168 ± 9 | |||||||||

| Factors . | No. of Colonies . | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Yolk Sac . | Fetal Liver . | BM . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||||||

| . | E + Meg . | E . | Meg . | Others . | E + Meg . | E . | Meg . | Others . | E + Meg . | E . | Meg . | Others . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| None | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 18 ± 3 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 12 ± 3 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 9 ± 1 | |||||||||

| EPO | 2 ± 1 | 30 ± 5 | 2 ± 1 | 21 ± 2 | 11 ± 1 | 27 ± 2 | 5 ± 1 | 9 ± 4 | 0 ± 0 | 21 ± 3 | 0 ± 0 | 10 ± 1 | |||||||||

| TPO | 6 ± 2 | 5 ± 1 | 73 ± 5 | 21 ± 2 | 2 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | 54 ± 5 | 10 ± 2 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 30 ± 1 | 10 ± 1 | |||||||||

| EPO + TPO | 61 ± 3 | 49 ± 4 | 68 ± 7 | 20 ± 3 | 24 ± 2 | 18 ± 1 | 69 ± 6 | 16 ± 2 | 3 ± 1 | 18 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 | 11 ± 2 | |||||||||

| IL-3 + EPO + TPO | 123 ± 7 | 43 ± 5 | 48 ± 5 | 57 ± 9 | 40 ± 2 | 25 ± 6 | 91 ± 1 | 98 ± 1 | 42 ± 4 | 19 ± 2 | 66 ± 9 | 168 ± 9 | |||||||||

A total of 7.5 × 104 day 10.5 yolk sac cells, 5 × 104 day 13.5 fetal liver cells, and 1 × 105 adult BM cells were plated onto a dish containing 2 U/mL EPO, 10 ng/mL TPO, 100 U/mL IL-3, and their combinations. E + Meg shows the number of colonies that contained both erythroid lineage cells and megakaryocytes. E and Meg shows the number of colonies that contained erythrocytes but no megakaryocytes and those that contained megakaryocytes but no erythrocytes, respectively. Data represent mean ± SE of quadruplicate cultures.

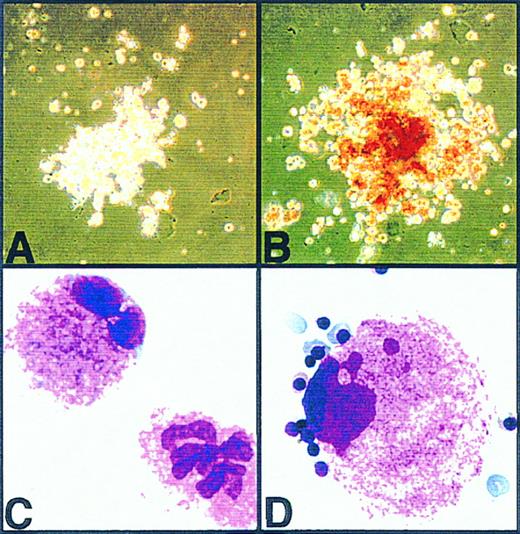

Erythroid-lineage cells, which appeared in these cultures, were morphologically adult-type definitive erythrocytes (Fig 1). These erythroid cells were negative by peroxidase-antiperoxidase (PAP) immunohistochemical staining with antiembryonic hemoglobin antiserum (data not shown).48 49 Thus, erythroid-lineage cells differentiated from yolk sac cells by the stimulation of TPO were definitive erythrocytes. In all the cultures of yolk sac, fetal liver, and adult BM, the addition of IL-3 significantly increased the number of erythroid colonies in the presence of both Epo and TPO (Table 1). E + Meg, E, and Meg colonies contained erythroid cells and megakaryocytes, erythroid cells, and megakaryocytes, respectively, almost exclusively, except for the culture containing IL-3 + Epo + TPO.

Photographs of phase-contrast microscopy and May-Giemsa staining of the colonies developed from day-10.5 mouse yolk sac cells. (A) and (C) show a pure megakaryocytic colony developed in the semisolid medium containing TPO (10 ng/mL) only. (B) and (D) show an erythro-megakaryocytic colony developed in medium containing Epo (2 U/mL) and TPO (10 ng/mL).

Photographs of phase-contrast microscopy and May-Giemsa staining of the colonies developed from day-10.5 mouse yolk sac cells. (A) and (C) show a pure megakaryocytic colony developed in the semisolid medium containing TPO (10 ng/mL) only. (B) and (D) show an erythro-megakaryocytic colony developed in medium containing Epo (2 U/mL) and TPO (10 ng/mL).

Augmentation of the size of erythroid colonies from yolk sac cells by TPO and IL-3.TPO increased not only the number of erythroid colonies, but also the numbers of the erythroid cells in individual colonies. The numbers of macroscopically visible red colonies (which should contain relatively large numbers of erythroid-lineage cells), microscopically identifiable erythroid colonies, and the ratio of these two types of colonies are presented in Table 2. Although the percentage of macroscopic erythroid colonies per microscopic ones was only 4% in the presence of Epo alone, the percentage increased to 24% by adding TPO. The number of microscopic erythroid colonies in the presence of Epo + TPO was comparable with that in the presence of IL-3 + Epo. However, the number was significantly higher in the culture with the combinatorial stimulation of IL-3 + Epo + TPO. The number of microscopic colonies in the presence of IL-3 + Epo + TPO was twice as many as those for Epo + TPO or IL-3 + Epo. This result suggests that at least two types of early erythroid progenitors exist in the mouse yolk sac; one responds to TPO and the other to IL-3. Presumably, there also exists the overlapping population that can respond to both IL-3 and TPO for stimulating erythroid colony formation.

Numbers of Colonies Containing Erythroid Cells From Day 10.5 Yolk Sac Cells

| Factors . | Macroscopic Erythroid Colonies . | Microscopic Erythroid Colonies . | Percentage of Macroscopic/Microscopic . |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 |

| EPO | 1 ± 1 | 39 ± 3 | 4 ± 2 |

| TPO | 0 ± 0 | 12 ± 3 | 0 ± 0 |

| EPO + TPO | 34 ± 4* | 141 ± 12* | 24 ± 3* |

| IL-3 | 15 ± 2† | 93 ± 7† | 16 ± 2† |

| IL-3 + EPO | 94 ± 8‡ | 149 ± 13 | 63 ± 2‡ |

| IL-3 + TPO | 35 ± 5 | 134 ± 4 | 26 ± 3 |

| IL-3 + EPO + TPO | 152 ± 3‡ | 236 ± 11‡ | 65 ± 1‡ |

| Factors . | Macroscopic Erythroid Colonies . | Microscopic Erythroid Colonies . | Percentage of Macroscopic/Microscopic . |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 |

| EPO | 1 ± 1 | 39 ± 3 | 4 ± 2 |

| TPO | 0 ± 0 | 12 ± 3 | 0 ± 0 |

| EPO + TPO | 34 ± 4* | 141 ± 12* | 24 ± 3* |

| IL-3 | 15 ± 2† | 93 ± 7† | 16 ± 2† |

| IL-3 + EPO | 94 ± 8‡ | 149 ± 13 | 63 ± 2‡ |

| IL-3 + TPO | 35 ± 5 | 134 ± 4 | 26 ± 3 |

| IL-3 + EPO + TPO | 152 ± 3‡ | 236 ± 11‡ | 65 ± 1‡ |

A total of 7.5 × 105 day 10.5 yolk sac cells were plated per dish in the presence of EPO, TPO, IL-3, and their combinations. Data represent mean ± SE of quadruplicate cultures.

P < .01 by Student's t-test with the groups of None, EPO alone, and TPO alone.

P < .01 by Student's t-test with the group of TPO alone.

P < .01 by Student's t-test with the group of EPO + TPO.

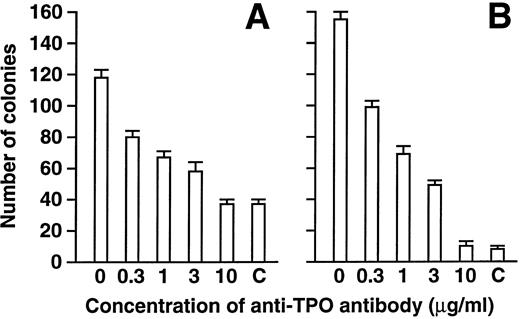

Effects of anti-TPO blocking antibody.The effects of anti-TPO blocking polyclonal antibody on erythroid and megakaryocyte colony formation by TPO and Epo were examined (Fig 2). Anti-TPO antibody showed dose-dependent inhibition of erythroid colony formation and megakaryocyte colony formation in a similar manner. Addition of anti-TPO antibody did not affect the growth of erythroid colony formation supported by Epo alone. Therefore, it is likely that the effects of TPO on erythroid colony formation are mediated through TPO–c-Mpl signaling.

Effects of anti-TPO antibody on erythroid and megakaryocytic colony formation supported by Epo and TPO. A total of 7.5 × 105 day 10.5 yolk sac cells were plated into methylcellulose cultures containing 2 U/mL Epo and 10 ng/mL TPO. Only Epo was added in the control (c) culture. Various concentrations of anti-TPO antibody were added as described. Numbers of colonies containing erythroid-lineage cells (A) and those containing megakaryocytes (B) are shown. Data represent mean ± standard errors (SE) of quadruplicate cultures.

Effects of anti-TPO antibody on erythroid and megakaryocytic colony formation supported by Epo and TPO. A total of 7.5 × 105 day 10.5 yolk sac cells were plated into methylcellulose cultures containing 2 U/mL Epo and 10 ng/mL TPO. Only Epo was added in the control (c) culture. Various concentrations of anti-TPO antibody were added as described. Numbers of colonies containing erythroid-lineage cells (A) and those containing megakaryocytes (B) are shown. Data represent mean ± standard errors (SE) of quadruplicate cultures.

Effect of TPO on the differentiation-induced ES cells.When ES cells were cocultured on the macrophage-CSF (M-CSF )–deficient stromal cell line, OP9, hematopoietic differentiation induction can be efficiently obtained.44,47 Recently, we found that embryonic primitive erythrocytes appeared around days 6 and 7 of the differentiation induction and the differentiation status was similar to yolk sac hematopoiesis.49 The day-6 differentiation-induced cells were cultured in the presence of Epo, TPO, or both (Table 3). Here again, TPO enhanced proliferation and differentiation of erythroid cells either in the presence or in the absence of Epo. The response of the day-6–induced cells to TPO was essentially the same as that of day-10.5 yolk sac cells.

Colony Formation From Day 6 In Vitro Differentiation-Induced ES Cells

| Factors . | E + Meg . | E . | Meg . | Others . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 3 ± 1 |

| EPO | 1 ± 1 | 13 ± 2 | 1 ± 1 | 7 ± 2 |

| TPO | 11 ± 23-150 | 2 ± 13-150 | 117 ± 23-150 | 1 ± 1 |

| EPO + TPO | 82 ± 63-151 | 51 ± 23-151 | 37 ± 53-151 | 5 ± 1 |

| IL3 + EPO + TPO | 119 ± 43-152 | 36 ± 5 | 60 ± 43-152 | 17 ± 13-152 |

| Factors . | E + Meg . | E . | Meg . | Others . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 3 ± 1 |

| EPO | 1 ± 1 | 13 ± 2 | 1 ± 1 | 7 ± 2 |

| TPO | 11 ± 23-150 | 2 ± 13-150 | 117 ± 23-150 | 1 ± 1 |

| EPO + TPO | 82 ± 63-151 | 51 ± 23-151 | 37 ± 53-151 | 5 ± 1 |

| IL3 + EPO + TPO | 119 ± 43-152 | 36 ± 5 | 60 ± 43-152 | 17 ± 13-152 |

A total of 3 × 104 day 6 in vitro differentiation-induced ES cells (for details, Materials and Methods) were plated into a dish containing 2 U/mL EPO, 10 ng/mL TPO, 100 U/mL IL-3, and their combinations. E + Meg, E and Meg shows the numbers of colonies the same as in Table 1. Data represent mean ± SE of quadruplicate cultures.

P < .01 by Student's t-test with the groups of None and TPO alone.

P < .01 by Student's t-test with the group of None, EPO alone, and TPO alone.

P < .05 by Student's t-test with the group of None, EPO alone, TPO alone, and EPO + TPO.

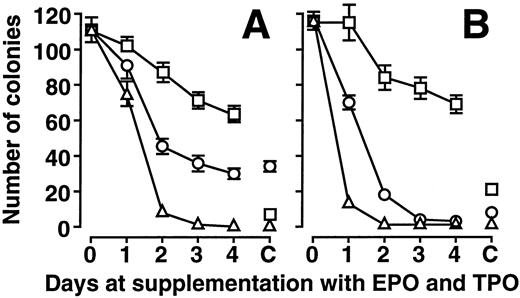

TPO as a survival factor for the erythroid progenitors.To examine whether either Epo or TPO could function as a survival factor for the erythroid progenitor cells, experiments of delayed addition of the cytokines were performed by using yolk sac cells and day-6 in vitro differentiation-induced ES cells (Fig 3).50 Methylcellulose semisolid culture was started supplemented with nothing, Epo alone, or TPO alone, and the culture media was supplemented with Epo and TPO, TPO, or Epo, respectively, at 1, 2, 3, and 4 days after the initiation of methylcellulose culture. No growth factors, Epo, and TPO were added in control culture of none, Epo, and TPO, respectively, throughout the culture.

Delayed addition experiment on yolk sac cells and day-6 in vitro differentiation-induced ES cells. The numbers of erythroid colonies from day-10.5 yolk sac cells (A) and day-6 in vitro differentiation-induced ES cells (B) are shown. ▵, ○, and □ show the numbers of colonies when the culture started with none, Epo alone, and TPO alone, respectively. The data at day 0 and “C” (control) show results of the culture that contained both Epo and TPO from day 0 and that which did not receive the supplement of the cytokines, respectively. Refer to text for details. Data represent mean ± SE of quadruplicate cultures.

Delayed addition experiment on yolk sac cells and day-6 in vitro differentiation-induced ES cells. The numbers of erythroid colonies from day-10.5 yolk sac cells (A) and day-6 in vitro differentiation-induced ES cells (B) are shown. ▵, ○, and □ show the numbers of colonies when the culture started with none, Epo alone, and TPO alone, respectively. The data at day 0 and “C” (control) show results of the culture that contained both Epo and TPO from day 0 and that which did not receive the supplement of the cytokines, respectively. Refer to text for details. Data represent mean ± SE of quadruplicate cultures.

When yolk sac cells were cultured with Epo alone or without growth factors, the numbers of erythroid colonies decreased rapidly. There were no significant differences between the numbers of erythroid colonies of control culture and those of delayed addition after day 2. In contrast, TPO restored a significant proportion of erythroid colony formation from yolk sac cells until day 4. In the case of day-6 in vitro-differentiated ES cells, the tendency was similar. Although Epo restored ≈60% of the erythroid colony-forming activity until day 1, such activity was hardly detected after day 3. On the other hand, TPO restored greater than 98% of the erythroid colony-forming activity until day 1. Furthermore, greater than 60% of the erythroid colony formation was maintained even until day 4 by TPO. These results clearly show that TPO was a survival factor of early erythroid progenitors in mouse yolk sac and day-6 in vitro-differentiated ES cells. In other words, TPO itself, not some other unknown factors in FCS, functioned as the enhancement factor of erythroid-lineage cells.

DISCUSSION

Early erythroid progenitors require the presence of both burst-promoting activity (BPA) and Epo for their proliferation and differentiation. Several growth factors such as IL-3, GM-CSF, SCF, and IL-9 have been identified as BPAs.21,23-25,50 Recently, a couple of groups reported that TPO also enhanced erythroid colony formation of BM or fetal liver progenitors, as well. Kobayashi et al39 reported that TPO functions as BPA on human CD34+ BM cells and cord blood cells, Kaushansky et al37 showed that TPO enhanced BPA activity of IL-3 and SCF on mouse BM erythroid progenitors, and Kieran et al51 showed that TPO rescued in vitro erythroid colony formation from fetal liver cells of Epo receptor lacking embryos in combination with SCF or with IL-3 and IL-11. In this study, we have shown that TPO has the ability to enhance proliferation and differentiation of early erythroid progenitors of murine yolk sac. This enhancement was augmented by Epo and, moreover, TPO alone stimulated proliferation and differentiation of erythroid cells. However, TPO did not have statistically significant influence on in vitro erythropoiesis of BM cells and fetal liver cells in our hands. The difference between the three reports cited above and our data might be due to the difference of FCS concentration and culture conditions39 or the combination with other cytokines such as SCF or IL-3.37 51

We cannot completely exclude the possibility that the erythroid-supporting activity of TPO is mediated by the Epo receptor and its signaling. But the following studies strongly suggest that TPO has the effects on erythroid progenitors through TPO-c–Mpl signaling. First, the effects of Epo plus TPO were much more than those of the additive, in not only the number but also the size of erythroid colonies (Table 2). Second, anti-TPO antibody inhibited erythroid colony formation (Fig 2). Third, TPO functioned as a survival factor for colony formation in the delayed-addition experiment (Fig 3) Meanwhile, it was examined whether previous treatment of TPO was sufficient to stimulate the early erythroid progenitor proliferation. TPO was added to the culture during the differentiation induction from ES cells between day 3 and day 6; afterwards, the cells were cultured in the methylcellulose media containing Epo only. However, the previous treatment of TPO did not enhance erythroid colony formation at all (data not shown). Thus, continuous stimulation of TPO seems important to support erythroid colony formation.

The percentage of the number of erythromegakaryocytic colonies produced by Epo + TPO per that of total colonies produced by IL-3 + Epo + TPO was calculated from Table 1. The percentage in yolk sac (23%) was much higher than that in adult BM (1%), indicating that the relative frequency of the bipotential erythromegakaryocytic progenitors, which responded to Epo + TPO stimulation, was very high in mouse yolk sac. Similarly, the percentage was high (35%) when in vitro differentiation-induced ES cells were used as a cell source. Therefore, the erythromegakaryocytic progenitors in mouse yolk sac and in vitro-differentiated ES cells should be a useful model to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of differentiation of two transcriptionally similar lineages, erythroid cells, and megakaryocytes.

The study on the developmental process of hematopoiesis is not well satisfied partially because of the difficulty involved in obtaining the in vivo materials from the developing mouse embryos. ES cells can be regarded as a substitute for the in vivo source, because ES cells are pluripotent cells derived from the inner cell mass of blastocysts and possess the ability to contribute to all lineages, including germline in chimeric animal once reintroduced into eight cell or blastocyst embryos.46 An efficient differentiation induction method by simple coculture of ES cells on novel stromal cell line OP9, which does not produce functional M-CSF was developed.43,44,47,49 Culture of day-6 differentiation induction with the method is similar to the status in yolk sac hematopoiesis, because it contains embryonic primitive erythrocytes as mature blood cells almost exclusively.49 TPO enhanced proliferation and differentiation of erythroid-lineage cells from these day-6 in vitro differentiation-induced ES cells, as it did for day 10.5 yolk sac cells. The day-6 culture also contained erythromegakaryocytic progenitors that responded to TPO and Epo, which supports the notion that the OP9 in vitro differentiation induction method is very useful to study the embryonic hematopoiesis. Obtaining the hematopoietic progenitors with this differentiation induction method is easier, less tedious, and less expensive than obtaining them from yolk sacs. Hematopoietic progenitors induced from genetically manipulated ES cells should facilitate understanding of the molecular events of hematopoiesis of the early stage of embryogenesis.

By using OP9 in vitro differentiation induction method, we recently reported on the development of embryonic primitive erythrocytes and adult definitive erythrocytes.49 Coculture of ES cells on OP9 cells sequentially gave rise to primitive erythrocytes and definitive erythrocytes with a time course similar to that for erythrocyte development in murine ontogeny. The data of growth factor requirement and limiting dilution analysis suggested that the primitive erythrocytes and definitive erythrocytes probably developed from different progenitors via a distinct differentiation pathway. Erythroid-lineage cells in the colonies, which were differentiated from yolk sac cells and day-6 in vitro differentiation-induced ES cells by the stimulation of TPO alone or of Epo + TPO, were definitive erythrocytes. In other words, TPO enhanced proliferation and differentiation of EryD progenitors but not of EryP progenitors.

In summary, TPO enhances proliferation and differentiation of erythroid-lineage cells from mouse yolk sac progenitors. Abundant erythroid progenitors and erythromegakaryocytic progenitors that respond to the stimulation of TPO and Epo exist in mouse yolk sac. In vitro differentiation-induced ES cells show very similar responses to TPO. The study of the effects of TPO on these erythroid and erythromegakaryocytic progenitors should promote the elucidation of the function and the mechanisms of TPO on erythropoiesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Professor T. Honjo of Kyoto University for spiritual and financial support, Dr H. Karasuyama for a kind gift of BMG-IL3 X63 cells, and Kirin Brewery Co, Ltd for a kind gift of Epo, TPO, and rat anti-TPO antibody.

Supported by the Naito Foundation, Tokyo, Japan; Yamanouchi Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders, Tokyo, Japan; and the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan.

Address reprint requests to Toru Nakano, MD, PhD, Department of Molecular Cell Biology, Research Institute for Microbial Diseases, Osaka University, Yamada-Oka 3-1, Suita, Osaka 565 Japan.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal