Abstract

We have recently demonstrated that a single injection of 4,900 IU of interleukin-12 (IL-12) on the day of bone marrow transplantation (BMT) markedly inhibits acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in a fully major histocompatibility complex plus minor antigen-mismatched BMT model (A/J → B10, H-2a → H-2b), in which donor CD4+ T cells are required for the induction of acute GVHD. We show here that donor CD8-dependent graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effects against EL4 (H-2b) leukemia/lymphoma can be preserved while GVHD is inhibited by IL-12 in this model. In mice in which IL-12 mediated a significant protective effect against GVHD, marked GVL effects of allogeneic T cells against EL4 were observed. GVL effects against EL4 depended on CD8-mediated alloreactivity, protection was not observed in recipients of either syngeneic (B10) or CD8-depleted allogeneic spleen cells. Furthermore, we analyzed IL-12–treated recipients of EL4 and A/J spleen cells which survived for more than 100 days. No EL4 cells were detected in these mice by flow cytometry, tissue culture, adoptive transfer, necropsies, or histologic examination. Both GVL effects and the inhibitory effect of IL-12 on GVHD were diminished by neutralizing anti–interferon-γ (IFN-γ) monoclonal antibody. This study demonstrates that IL-12–induced IFN-γ production plays a role in the protective effect of IL-12 against GVHD. Furthermore, IFN-γ is involved in the GVL effect against EL4 leukemia, demonstrating that protection from CD4-mediated GVHD and CD8-dependent anti-leukemic activity can be provided by a single cytokine, IFN-γ. These observations may provide the basis for a new approach to inhibiting GVHD while preserving GVL effects of alloreactivity.

GRAFT-VERSUS-HOST disease (GVHD) is a major obstacle to clinical bone marrow transplantation (BMT), since its incidence is prohibitively high when extensive HLA barriers are crossed, and many patients do not have an HLA-matched donor.1,2 Although many approaches to controlling GVHD have been attempted, and a reduction of GVHD has been achieved with T-cell depletion (TCD) of donor bone marrow and the use of nonspecific immunosuppressive drugs, the rates of allograft failure3 and leukemic relapse4,5 are also increased by these approaches. Thus, the ideal clinically applicable approach to HLA-mismatched BMT would selectively inhibit the GVHD-promoting activity of allogeneic T cells while preserving allogeneic T-cell–mediated graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effects. When HLA non-genotypically–identical unrelated donor transplants have been performed, increased GVHD has been at least partially offset by decreased leukemic relapse rates.6 Similar differences have been observed when single HLA antigen-mismatched transplants have been compared with HLA-identical transplants.7-9 These results indicate that GVL effects might be even greater if BMT could be performed in the setting of wider HLA mismatches. However, the full potential of this GVL effect cannot be exploited unless GVHD can, at the same time, be avoided. We have recently demonstrated that GVL effects of allogeneic T cells can be preserved independently of GVHD by using immunobiological therapy, such as high-dose IL-2.10-13

Interleukin-12 (IL-12) is produced in response to bacteria, bacterial products, or intracellular parasites by monocytes-macrophages, and other accessory cells.14 This cytokine induces Th1-associated responses by stimulating T cells and natural killer (NK) cells to produce IFN-γ, and by inhibiting T cell production of IL-4.15-17 IL-12 also enhances cytolytic activity of T cells and NK cells,18 and has been shown to enhance protective immunity against some intracellular parasites and to promote antitumor immunity.19,20 We have recently demonstrated that IL-12 has a significant inhibitory effect on GVHD.21 Since IL-12 is not globally immunosuppressive and might even have antileukemic activity of its own, we have now examined the possibility that IL-12 could preserve GVL effects of donor T cells in the EL4 leukemia/lymphoma model, while GVHD is inhibited. Our results indicate that IL-12 treatment permits GVL-promoting activities of allogeneic T cells to occur independently of apparent GVHD. Marked GVL effects were observed in mice in which IL-12 mediated a significant protective effect against GVHD. We also analyzed the contributions of IFN-γ and allogeneic T cell subsets to GVL effects in IL-12–treated leukemic recipients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice. Specific pathogen-free female C57BL/10SnCR (B10, H-2b, KbIbDb), C57BL/6SnCR (B6, H-2b, KbIbDb) and A/J (H-2a, KaIaDd) mice were obtained from the Frederick Cancer Research Facility (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Animals were housed in sterilized microisolator cages and received autoclaved feed and autoclaved, acidified drinking water.

Whole body irradiation (WBI) and BMT. Recipient mice (B10 or B6) were lethally irradiated (10.25 Gy, 137Cs source, 1.1 Gy/min) and reconstituted within 4 to 8 hours by a single 1 mL intravenous inoculum containing 5 × 106 TCD B10 or B6 BMC plus 10 × 106 A/J BMC and 15 to 18 × 106 A/J spleen cells, or by 5 × 106 TCD B10 or B6 BMC with or without 15 to 18 × 106 B10 or B6 spleen cells (syngeneic control group). TCD syngeneic BMC enhances IL-12–mediated inhibition of GVHD, even though the host-type cells are eliminated within 1 week after BMT.21 Therefore, in order to evaluate GVL effects in IL-12–treated allogeneic recipients, TCD B10 or B6 BMC were administered in all experiments to achieve the best GVHD protection possible. Host-type (B10 or B6) BMC and, in some experiments, allogeneic BMC and spleen cells, were depleted of T cells, or of CD4+ or CD8+ cells by incubating cells with anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody (MoAb) (GK1.5 ascites)22 and/or anti-CD8 MoAb (2.43 ascites)23 for 30 minutes at room temperature, and followed by incubation with low toxicity rabbit complement (1:14 dilution) for 45 minutes at 37°C, as previously described.12 T-cell depletion was analyzed by flow cytometry using indirect staining as described,24 and completeness of depletion (less than 0.5% cells of the depleted phenotype remaining) was verified in each experiment. In adoptive BMT, secondary recipients (B10) were lethally irradiated and reconstituted with CD4- and CD8-depleted BMC and spleen cells prepared from long-term (more than 100 days) surviving nonleukemic (as control) and leukemic recipients of allogeneic BMT. These secondary recipients also received 5 × 106 fresh TCD B10 BMC. To avoid bias from cage-related effects, animals were randomized before and after BMT as described.10 Survival was followed for 100 days.

IL-12 administration. Murine recombinant IL-12 (kindly provided by Dr Stanley F. Wolf, Genetics Institute, Cambridge, MA), with specific activity of 4.9 to 5.5 × 106 U/mg, was injected intraperitoneally (IP) into recipient mice (4,900 IU/mouse) in a single injection approximately 1 hour before BMT.

EL4 leukemia experiments. The EL4 leukemia model we have previously described11,25 was used. EL4F cells (referred to here as EL4), a sub-line of the B6 T-cell leukemia/lymphoma EL4, were thawed from frozen vials and maintained in culture for 4 to 14 days before each experiment, and 500 cells were administered on day 0 along with BMC and spleen cells in a single 1 mL intravenous (IV) injection. Carcasses were saved in formalin after death or euthanasia, and in some leukemic and nonleukemic mice, the spleen, liver, kidney, and lung were embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Necropsies and histologic analysis were performed on randomly chosen samples. The presence of tumor at death was determined by gross autopsy and/or histologic observation by an observer who was unaware of which treatment group the carcasses belonged to, as previously described.25

Flow cytometric (FCM) analysis. FCM analysis of peripheral white blood cells (WBC) was performed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). WBC were prepared by hypotonic shock, as described.26 Cells were stained with biotinylated anti–H-2Dd MoAb 34-2-1227 and FITC-labeled rat antimouse CD4 MoAb GK1.5,22 rat antimouse CD8 MoAb 2.43,23 or rat antimouse Thy1.2 for 30 minutes at 4°C, then washed and incubated for 15 minutes at 4°C with phycoerythrin/streptavidin (PEA). In order to block nonspecific FcγR binding of labeled antibodies, 10 μL of undiluted culture supernatant of 2.4G2 (rat antimouse FcγR MoAb)28 was added to the first incubation. Mouse IgG2a MoAb HOPC-1 was used as a nonstaining negative control antibody. Dead cells were excluded by gating out low forward scatter/high propidium iodide-retaining cells.

Anti–IFN-γ MoAb administration. Rat IgG1 antimouse interferon-γ MoAb R4-6A229 was ammonium sulfate precipitated from ascites prepared in BALB/c nude mice. Antibody content was quantified using rat IgG-specific inhibition ELISA. A single injection of 2.5, 5, or 10 mg of R4-6A2 was administered on day 1 with respect to BMT.

Statistical analysis. Survival data were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meyer method of life table analysis, and statistical analysis was performed with the Mantel-Haenzsen test. A P value of less than .05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

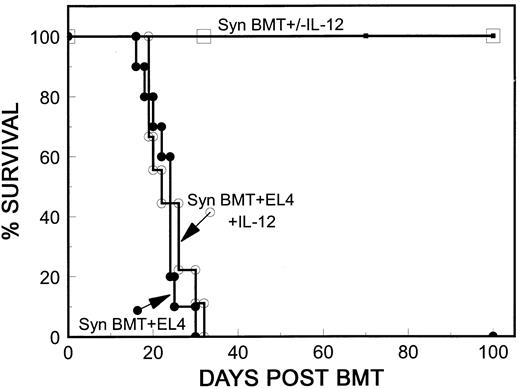

Syngeneic spleen cells do not mediate antitumor activity in IL-12–treated mice. The EL4 H-2b leukemia administered as we have recently described11,25 is highly lethal, and as few as 100 cells are sufficient to kill lethally irradiated, syngeneically reconstituted H-2b mice. Since IL-12 has been shown to promote antitumor immunity,15 19 we first investigated whether IL-12 could mediate antileukemia effects of its own, by promotion of host immunity. We compared tumor-induced mortality in control mice with that in IL-12–treated B10 mice after syngeneic BMT. B10 mice were lethally irradiated, and injected with 500 EL4 cells along with 5 × 106 TCD B10 BMC and 15 × 106 B10 spleen cells. As shown in Fig 1, a single dose of 4,900 IU of IL-12 had no effect on tumor-induced mortality. In both the control (Syn BMT + EL4) and the IL-12–treated (Syn BMT + EL4 + IL-12) group, almost all mice were dead by 30 days posttransplantation, and marked enlargement of the spleen and/or kidney was observed in 18 of 19 carcasses at autopsy.

Syngeneic spleen cells do not mediate an anti-leukemia effect in IL-12–treated mice. Results of two experiments that gave similar results are combined. B10 mice were treated with 10.25 Gy WBI and received 5 × 106 TCD B10 BMC, 15 or 18 × 106 B10 spleen cells plus 500 EL4 cells with no further treatment (•; n = 10) or with 4,900 IU IL-12 intraperitoneally on day 0 (○; n = 9). Nonleukemic control mice received similar inocula without EL4 cells with no further treatment (□; n = 6) or with 4,900 IU intraperitoneally (▪; n = 6).

Syngeneic spleen cells do not mediate an anti-leukemia effect in IL-12–treated mice. Results of two experiments that gave similar results are combined. B10 mice were treated with 10.25 Gy WBI and received 5 × 106 TCD B10 BMC, 15 or 18 × 106 B10 spleen cells plus 500 EL4 cells with no further treatment (•; n = 10) or with 4,900 IU IL-12 intraperitoneally on day 0 (○; n = 9). Nonleukemic control mice received similar inocula without EL4 cells with no further treatment (□; n = 6) or with 4,900 IU intraperitoneally (▪; n = 6).

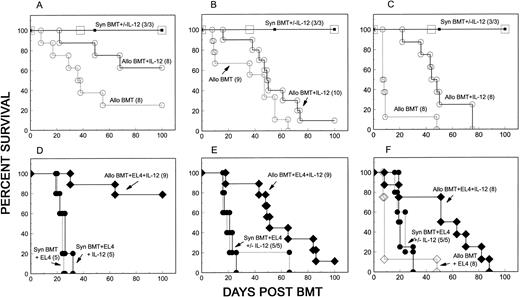

Preservation of allogeneic GVL effects in IL-12–treated mice. We next evaluated whether allogeneic GVL effects could be preserved while GVHD is inhibited by IL-12 in the EL4 leukemia model.12 Lethally irradiated B10 mice received a mixture of 5 × 106 syngeneic (B10) TCD BMC, fully MHC plus multiple minor antigen-mismatched A/J BMC (10 × 106) and A/J spleen cells (15 to 18 × 106), plus 500 EL4 cells. A syngeneic control group received the same number of B10 TCD BMC and spleen cells. Figure 2 shows the results from three independent experiments in which different degrees of GVHD were observed in the untreated allogeneic BMT recipients. In nonleukemic recipients, GVHD mortality was clearly delayed in IL-12–treated mice (Allo BMT + IL-12) when compared with untreated controls, which received similar inocula in each experiment (Allo BMT) (Fig 2, A-C) (P < .01 for two experiments shown in A and C). A similar level of protection from GVHD was also observed in IL-12–treated leukemic recipients (Fig 2, D-F ). In addition, administration of EL4 did not result in a detectable increase in mortality in these mice, as survival curves were similar in groups receiving (Allo BMT + EL4 + IL-12) or not receiving (Allo BMT + IL-12) EL4 (Fig 2, A v D, B v E, C v F ). Allogeneic cells were necessary for an antileukemic effect in IL-12–treated mice, as IL-12 treatment did not result in a detectable GVL effect in syngeneic controls in the same experiments (Fig 2, D-F ). Therefore, the GVL effect of allogeneic spleen cells was preserved while allogeneic spleen cell-mediated GVHD was inhibited by IL-12.

Preservation of allogeneic GVL effects in IL-12–treated mice. Results from three individual experiments are shown in each column. B10 (H-2b) mice were lethally irradiated on day 0. (A through C) Nonleukemic mice received 5 × 106 TCD B10 BMC and 15 to 18 × 106 B10 spleen cells with or without IL-12 treatment (Syn BMT +/− IL-12), or 5 × 106 TCD B10 BMC plus 10 × 106 A/J BMC and 15 to 18 × 106 A/J spleen cells with (Allo BMT + IL-12) or without (Allo BMT) IL-12 treatment. (D through F ) Leukemic recipients in the same experiments received 5 × 106 TCD B10 BMC and 15 to 18 × 106 B10 spleen cells alone with (Syn BMT + EL4 + IL-12) or without (Syn BMT + EL4) IL-12 treatment, or 5 × 106 TCD BMC plus 10 × 106 A/J BMC and 15 to 18 × 106 A/J spleen cells with (Allo BMT + EL4 + IL-12) or without (Allo BMT + EL4) IL-12 treatment. All leukemic recipients received 500 H-2b EL4 cells on the day of BMT.

Preservation of allogeneic GVL effects in IL-12–treated mice. Results from three individual experiments are shown in each column. B10 (H-2b) mice were lethally irradiated on day 0. (A through C) Nonleukemic mice received 5 × 106 TCD B10 BMC and 15 to 18 × 106 B10 spleen cells with or without IL-12 treatment (Syn BMT +/− IL-12), or 5 × 106 TCD B10 BMC plus 10 × 106 A/J BMC and 15 to 18 × 106 A/J spleen cells with (Allo BMT + IL-12) or without (Allo BMT) IL-12 treatment. (D through F ) Leukemic recipients in the same experiments received 5 × 106 TCD B10 BMC and 15 to 18 × 106 B10 spleen cells alone with (Syn BMT + EL4 + IL-12) or without (Syn BMT + EL4) IL-12 treatment, or 5 × 106 TCD BMC plus 10 × 106 A/J BMC and 15 to 18 × 106 A/J spleen cells with (Allo BMT + EL4 + IL-12) or without (Allo BMT + EL4) IL-12 treatment. All leukemic recipients received 500 H-2b EL4 cells on the day of BMT.

Autopsy analysis was performed in randomly selected carcasses without knowledge of which treatment the animals had received. A total of 91 carcasses (45 nonleukemic and 46 leukemic recipients) from the three experiments shown in Fig 2 were examined. As shown in Table 1, gross evidence for tumor, which was detected in almost all leukemic recipients of B10 TCD BMC and spleen cells, was not found in IL-12–treated leukemic recipients of B10 TCD BMC plus A/J BMC and spleen cells. It was impossible to detect a GVL effect of allogeneic spleen cells in leukemic mice not receiving IL-12, as most mice died of acute GVHD before EL4-induced death began in syngeneic control mice (Allo BMT + EL4) (Table 1, and Fig 2 C and F ). Leukemic infiltration of kidneys, liver, spleen, or lung was readily apparent in the syngeneic BMT controls receiving EL4 (Syn BMT + EL4 +/− IL-12), but was not detected in IL-12–protected recipients of allogeneic cells (Allo BMT + EL4 + IL-12) by histologic analysis.

Gross Evidence for Tumor at Autopsy Was Detected in All Syngeneic EL4 Recipients, But Not in IL-12–Protected Allogeneic EL4 Recipients

| Group (n) . | Tumor at Autopsy . |

|---|---|

| . | (no. with tumor/total evaluated) . |

| Syn BMT +/− IL-12 (9/9) | 0/18 |

| Allo BMT (25) | 0/15 |

| Allo BMT + IL-12 (26) | 0/12 |

| Syn BMT + EL4 (15) | 12/13 |

| Syn BMT + EL4 + IL-12 (15) | 13/13 |

| Allo BMT + EL4 (8) | 0/5* |

| Allo BMT + EL4 + IL-12 (26) | 0/15 |

| Group (n) . | Tumor at Autopsy . |

|---|---|

| . | (no. with tumor/total evaluated) . |

| Syn BMT +/− IL-12 (9/9) | 0/18 |

| Allo BMT (25) | 0/15 |

| Allo BMT + IL-12 (26) | 0/12 |

| Syn BMT + EL4 (15) | 12/13 |

| Syn BMT + EL4 + IL-12 (15) | 13/13 |

| Allo BMT + EL4 (8) | 0/5* |

| Allo BMT + EL4 + IL-12 (26) | 0/15 |

All animals died of GVHD by 8 days posttransplant.

To obtain an indication of the magnitude of GVL effects in IL-12–treated allogeneic recipients, we titrated the number of EL4 cells administered to syngeneic and allogeneic recipients. Tumor-induced mortality in syngeneic leukemic recipients was significantly accelerated by increasing the dose of EL4 cells. However, similar mortality was observed in IL-12–treated allogeneic recipients of 25,000 EL4 cells (median survival time [MST] = 19.5 days) as was observed in IL-12–treated syngeneic recipients of only 500 EL4 cells (MST = 19 days). In this experiment, no mortality could be attributed to leukemia in IL-12–treated recipients of 500 or 5,000 EL4 cells with allogeneic BMT, as no tumor was detected in 16 carcasses examined, and no increase in mortality was observed compared with recipients of allogeneic BMT without EL4, with IL-12. In syngeneic recipients of EL4, survival times were significantly shorter in recipients of 5,000 (MST = 16 days) or 25,000 (MST = 15 days) EL4 cells compared with recipients of 500 EL4 cells (MST = 19 days; P < .01). All 15 animals in all dose groups showed gross tumor at autopsy. Together, these results show that IL-12–treated allogeneic BMT recipients resisted more than 1.5 logs greater tumor burden than syngeneic controls.

EL4 cells are undetectable in IL-12–treated recipients of allogeneic spleen cells. Inhibition of leukemic mortality in IL-12–treated EL4 recipients that received B10 TCD BMC plus A/J BMC and spleen cells suggested that leukemic growth was inhibited. We next evaluated whether EL4 cells were completely eradicated by allogeneic cell-mediated GVL effects in these animals. BMC, thymocytes, spleen cells, peripheral blood cells, and tissue fractions of liver and kidney were prepared from long-term surviving IL-12–treated EL4 recipients (nine mice from experiments shown in Fig 2D and E) when they were killed after 100 days of follow-up. These cells were cultured in vitro for 1 month, and no EL4 cells grew in the cultures. Thymocytes, spleen cells, BMC, and peripheral WBC from these animals were also analyzed by two-color FACS. Since T cells in long-term surviving IL-12–treated recipients are of donor-type (A/J, H-2Dd),30 31 and EL4 cells are H-2Db+ and Thy1.2+, we stained these cells with FITC-labeled antimouse Thy1.2 MoAb and biotin-labeled anti–H-2Dd MoAb plus PEA. No EL4 cells with the H-2Dd−, Thy1.2+ phenotype were detected, as all Thy1.2+ cells were donor-type (H-2Dd+) in both nonleukemic and leukemic recipients of allogeneic BMT (data not shown).

To further test for residual leukemic cells in IL-12–protected recipients of EL4 and allogeneic cells, we transferred TCD BMC and TCD spleen cells from these long-term (more than 100 days) surviving IL-12–treated allogeneic EL4 recipients (n = 11) and nonleukemic recipients (as controls, n = 6), along with TCD B10 BMC, into lethally irradiated secondary B10 recipients (one donor to two recipients). The spleen is a major site of leukemic infiltration in this EL4 model.25 Potentially GVH-reactive A/J CD4 and CD8 T cells were eliminated from these inocula in order to allow any residual EL4 cells the best opportunity to grow in secondary host-type recipients. Mixed chimerism was observed in these secondary recipients by flow cytometric analysis (data not shown), indicating that GVH-reactive T cells were completely depleted from the spleens and marrow of the donor chimeras.32-34 However, no leukemia-induced mortality was observed by 100 days of follow-up, and no gross evidence for tumor was detected by autopsy in any of 22 mice killed 100 days following transfer. Although it is possible that IL-12–protected allogeneic leukemic recipients still harbored very small numbers of EL4 cells below the detection limit of the assays used, the absence of detectable EL4 cells by all assays, including autopsy, histology, FACS, tissue culture, and adoptive transfer, suggest that the expansion of EL4 leukemic cells had been completely inhibited and most or all EL4 cells had been eradicated from IL-12–treated allogeneic BMT recipients.

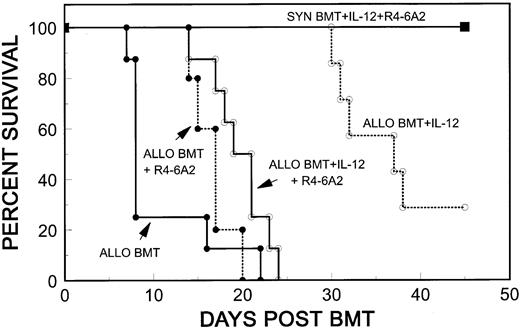

Role of IFN-γ in IL-12–mediated GVHD protection. Our previous results showed that IL-12 treatment markedly increases serum IFN-γ levels on days 2 and 3 post-BMT, and that the later, GVHD-associated rise in serum IFN-γ on day 4 is markedly inhibited.21,35 Therefore, we investigated the role of IL-12–induced IFN-γ production in the inhibitory effect against GVHD and in GVL effects of allogeneic spleen cells in IL-12–treated mice. On day 1 post-BMT, we injected 2.5 mg of R4-6A2, a neutralizing rat antimouse IFN-γ MoAb29 into IL-12–treated B10 mice, which received 5 × 106 B10 TCD BMC plus 10 × 106 A/J BMC and 15 × 106 A/J spleen cells. Although GVHD-induced mortality was slightly delayed by R4-6A2 (Allo BMT + R4-6A2) compared with GVHD controls, which received similar BMT inocula without R4-6A2 (Allo BMT), the delay did not achieve statistical significance (Fig 3). As usual, IL-12 treatment induced a significant delay in GVHD mortality (Allo BMT + IL-12) compared with GVHD controls (Allo BMT) (P < .005). This delay was markedly inhibited by R4-6A2 (Allo BMT + IL-12 + R4-6A2) (P < .005) (Fig 3), so that the time of mortality in the group receiving IL-12 and R4-6A2 (Allo BMT + IL-12 + R4-6A2) was similar to that of the group treated with R4-6A2 alone (Allo BMT + R4-6A2) (Fig 3). We repeated this experiment using different doses of R4-6A2 (2.5, 5, or 10 mg per mouse), and similar results were observed (data not shown).

R4-6A2, a rat antimouse IFN-γ MoAb, inhibits the protective effect of IL-12 against GVHD. Lethally irradiated B10 mice received 5 × 106 TCD B10 BMC plus 10 × 106 A/J BMC and 15 × 106 A/J spleen cells with no further treatment (Allo BMT, n = 8), or with IL-12 (Allo BMT + IL-12, n = 8) or R4-6A2 (Allo BMT + R4-6A2, n = 5), or both (Allo BMT + IL-12 + R4-6A2, n = 8). Syngeneic controls received 5 × 106 TCD B10 BMC with treatments of IL-12 and R4-6A2 (SYN BMT + IL-12 + R4-6A2, n = 3). Four thousand nine hundred units IL-12 and 2.5 mg R4-6A2 were administered by i.p. injection on day 0 and day 1 with respect to BMT, respectively.

R4-6A2, a rat antimouse IFN-γ MoAb, inhibits the protective effect of IL-12 against GVHD. Lethally irradiated B10 mice received 5 × 106 TCD B10 BMC plus 10 × 106 A/J BMC and 15 × 106 A/J spleen cells with no further treatment (Allo BMT, n = 8), or with IL-12 (Allo BMT + IL-12, n = 8) or R4-6A2 (Allo BMT + R4-6A2, n = 5), or both (Allo BMT + IL-12 + R4-6A2, n = 8). Syngeneic controls received 5 × 106 TCD B10 BMC with treatments of IL-12 and R4-6A2 (SYN BMT + IL-12 + R4-6A2, n = 3). Four thousand nine hundred units IL-12 and 2.5 mg R4-6A2 were administered by i.p. injection on day 0 and day 1 with respect to BMT, respectively.

Role of IFN-γ in GVL effects of allogeneic cells in IL-12–treated mice. We next investigated the possible role of IFN-γ in the GVL effects of allogeneic spleen cells in IL-12–treated mice. As shown in Table 2, IL-12–treated leukemic recipients of TCD B10 BMC plus A/J BMC and spleen cells (Allo BMT, IL-12, EL4) were significantly protected from both GVHD- and leukemia-induced mortality when compared with GVHD control recipients of similar inocula without IL-12 (Allo BMT) (P < .01), and syngeneic leukemic recipients of B10 TCD BMC and EL4 cells (Syn BMT, EL4) (P < .01), respectively. The GVL effect of allogeneic cells was significantly reduced by injecting R4-6A2 on day 1 post-BMT. A significant acceleration in mortality (P < .05) was detected in R4-6A2–treated, IL-12–treated leukemic recipients (Allo BMT, IL-12, R4-6A2, EL4) compared with IL-12–treated leukemic allogeneic BMT controls (Allo BMT, IL-12, EL4).

Role of IFN-γ in the GVL Effect of Allogeneic Spleen Cells in IL-12–Treated Mice

| Group (n) . | Survival (%) . | Tumor at Autopsy (no. with tumor/total evaluated) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Day 10 . | Day 35 . | Day 64 . | . |

| Syn BMT (3) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0/3 |

| Syn BMT, EL4 (5)* | 100 | 0 | 0 | 5/5 |

| Allo BMT (8) | 38 | 13 | 0 | 0/7 |

| Allo BMT, IL-12 (7) | 100 | 86 | 75 | 0/8 |

| Allo BMT, IL-12, R4-6A2 (8)† | 100 | 50 | 12 | 0/7 |

| Allo BMT, IL-12, EL4 (9) | 100 | 100 | 56 | 0/8 |

| Allo BMT, IL-12, R4-6A2, EL4 (9) | 100 | 33 | 11 | 4/9 |

| Group (n) . | Survival (%) . | Tumor at Autopsy (no. with tumor/total evaluated) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Day 10 . | Day 35 . | Day 64 . | . |

| Syn BMT (3) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0/3 |

| Syn BMT, EL4 (5)* | 100 | 0 | 0 | 5/5 |

| Allo BMT (8) | 38 | 13 | 0 | 0/7 |

| Allo BMT, IL-12 (7) | 100 | 86 | 75 | 0/8 |

| Allo BMT, IL-12, R4-6A2 (8)† | 100 | 50 | 12 | 0/7 |

| Allo BMT, IL-12, EL4 (9) | 100 | 100 | 56 | 0/8 |

| Allo BMT, IL-12, R4-6A2, EL4 (9) | 100 | 33 | 11 | 4/9 |

All EL4 recipients were injected with 500 EL4 cells among with BMC and spleen cells.

R4-6A2: neutralizing rat antimouse IFN-γ MoAb, 2.5 mg administered IP on day 1.

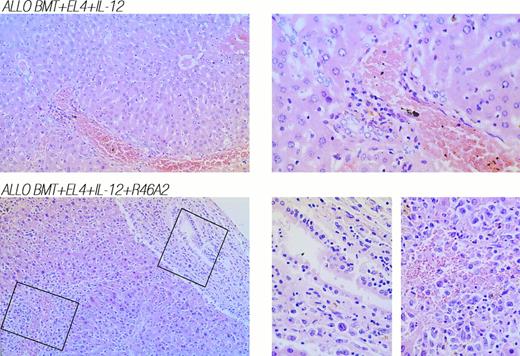

Since R4-6A2 diminished the protective effect of IL-12 against GVHD in nonleukemic allogeneic BMT mice (Fig 3 and Table 2), this acceleration of mortality in EL4 recipients could reflect a loss of GVHD protection, a loss of GVL effects, or both. However, autopsy and histologic analysis indicated that the GVL effect in IL-12–treated mice was partially impaired by R4-6A2 treatment, as gross evidence of leukemia, similar to that observed in syngeneic EL4 controls (Syn BMT, EL4), was detected in four of nine of these animals (Allo BMT, IL-12, R4-6A2, EL4) (Table 2), and leukemic infiltration of liver, kidney, or lung was observed in three of the five mice not showing gross tumor at autopsy. The coexistence of diffuse invasion of leukemic cells and severe GVHD-associated mononuclear cell infiltration was strikingly evident in the livers of IL-12–treated leukemic allogeneic BMT recipients that were treated with R4-6A2 (Fig 4, bottom row). In contrast, no evidence for leukemia was detected at autopsy of IL-12–protected leukemic recipients of similar inocula without R4-6A2 (Allo BMT, IL-12, EL4) (Table 2), and no leukemic infiltration of liver, kidney, or lung was observed by histologic analysis. Only mild GVHD-associated mononuclear cell infiltration of the liver was observed in mice that died at later times in this group (Fig 4, top row).

Neutralization of IFN-γ with MoAb R4-6A2 in leukemic allogeneic BMT recipients treated with IL-12 results in diffuse invasion of leukemic cells and severe GVHD-associated mononuclear cell infiltration of the liver. (Top) Liver was obtained from an IL-12–protected leukemic recipient of allogeneic BMT that died on day 51. (Bottom) Liver was obtained from an IL-12–treated leukemic recipient of allogeneic BMT plus neutralizing anti–IFN-γ MoAb R4-6A2 that died on day 42. 160× and 400× photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin stains are shown in left and right panels, respectively.

Neutralization of IFN-γ with MoAb R4-6A2 in leukemic allogeneic BMT recipients treated with IL-12 results in diffuse invasion of leukemic cells and severe GVHD-associated mononuclear cell infiltration of the liver. (Top) Liver was obtained from an IL-12–protected leukemic recipient of allogeneic BMT that died on day 51. (Bottom) Liver was obtained from an IL-12–treated leukemic recipient of allogeneic BMT plus neutralizing anti–IFN-γ MoAb R4-6A2 that died on day 42. 160× and 400× photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin stains are shown in left and right panels, respectively.

Together, our results show that IFN-γ is involved in the protective effect of IL-12 against acute GVHD, and is also involved in the GVL effect of allogeneic cells against EL4 leukemia in IL-12–treated mice.

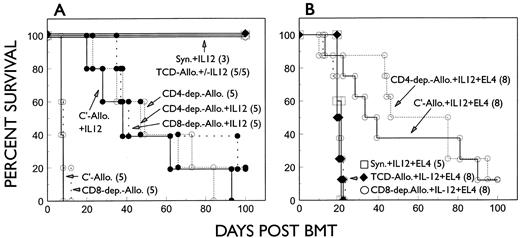

Role of T-cell subsets in GVL effects in IL-12–treated mice. Since GVL effects against EL4 leukemia in the model used in this study have been shown to be CD8-dependent and CD4-independent in untreated recipients of allogeneic BMC and spleen cells,12 we next evaluated the contribution of donor T-cell subsets to GVL effects in IL-12–treated EL4 recipients. Lethally irradiated B6 mice received 5 × 106 TCD B6 BMC alone, or with 10 × 106 TCD A/J BMC plus 15 × 106 T-cell–depleted (CD4 or CD8 or both CD4 and CD8) or nondepleted (treated with complement alone) A/J spleen cells. Leukemic mice received similar inocula plus 500 EL4 cells. As shown in Fig 5, B6 mice receiving CD8-depleted A/J spleen cells showed similar GVHD mortality to B6 recipients of complement-treated A/J spleen cells. Removing donor CD8+ cells did not abrogate the protective effect of IL-12 against GVHD (Fig 5A). As CD4+ T cells are required for the induction of acute GVHD in this strain combination, no mice died in the early period in the group receiving CD4-depleted A/J spleen cells. Most recipients in this group died subsequently with sub-acute or chronic GVHD. A single injection of IL-12 on the day of BMT had no effect on this CD8-mediated, delayed GVHD. IL-12 neither inhibited nor accelerated the GVHD observed in mice receiving CD4-depleted A/J spleen cells (Fig 5A). Although depletion of donor CD8+ T cells did not influence the course of acute GVHD or IL-12–mediated GVHD protection, recipients of CD8-depleted A/J spleen cells showed a complete loss of GVL effects against EL4 leukemia. Tumor-related mortality in IL-12–treated EL4 recipients of CD8-depleted A/J spleen cells was similar to that in IL-12–treated animals that received TCD A/J spleen cells or TCD B6 BMC alone (Fig 5B). In addition, gross evidence for leukemia was clearly detected by autopsy in these leukemic recipients of CD8-depleted A/J spleen cells (data not shown). Similar rates of EL4-induced mortality were observed in IL-12–treated recipients of CD4- plus CD8-depleted (TCD) A/J spleen cells and TCD syngeneic BMC alone (Fig 5B), suggesting that CD8-independent NK cells were not directly involved in allogeneic spleen cell-mediated GVL effects.

GVL effect of allogeneic inocula against EL4 in IL-12–treated EL4 recipients is CD8-dependent. Lethally irradiated B6 mice were reconstituted with 5 × 106 B6 TCD BMC plus 10 × 106 TCD A/J BMC and 15 × 106 A/J spleen cells depleted of CD4- (CD4-dep.-Allo), CD8- (CD8-dep.-Allo), or CD4 plus CD8 (TCD-Allo) cells. Nonleukemic and leukemic recipients of 500 EL4 cells that received similar BMT inocula are shown in (A) and (B), respectively.

GVL effect of allogeneic inocula against EL4 in IL-12–treated EL4 recipients is CD8-dependent. Lethally irradiated B6 mice were reconstituted with 5 × 106 B6 TCD BMC plus 10 × 106 TCD A/J BMC and 15 × 106 A/J spleen cells depleted of CD4- (CD4-dep.-Allo), CD8- (CD8-dep.-Allo), or CD4 plus CD8 (TCD-Allo) cells. Nonleukemic and leukemic recipients of 500 EL4 cells that received similar BMT inocula are shown in (A) and (B), respectively.

In contrast to these results, a significant GVL effect against EL4 leukemia was observed in IL-12–treated EL4 recipients of CD4-depleted A/J spleen cells in the same experiment (Fig 5B). Almost all mice in groups that received CD4-depleted A/J spleen cells plus EL4 cells survived longer than syngeneic leukemic controls (Fig 5B). No gross evidence for leukemia, as was detected in all IL-12–treated EL4 recipients of B6 TCD BMC, was observed in IL-12–treated mice receiving CD4-depleted A/J spleen cells plus EL4 by autopsy. Furthermore, the mortality in IL-12–treated mice receiving CD4-depleted A/J spleen cells plus EL4 cells was similar to that in IL-12–treated or control mice that received similar BMT inocula without EL4, indicating that EL4-induced mortality was inhibited by giving CD4-depleted A/J spleen cells. Together, these results indicate that GVL effects against EL4 leukemia are CD8-dependent, and that treatment with IL-12 can preserve this CD8-mediated GVL effect without accelerating CD8-induced GVHD. Furthermore, these results show that IL-12 can inhibit GVHD induced by CD4+ T cells without CD8+ cells.

Similar results were observed in a repeat experiment in which GVL effects were observed in IL-12–treated recipients of non–CD8-depleted A/J spleen cells. Autopsy results showed evidence for leukemia in all EL4 recipients of CD8-depleted or TCD A/J spleen cells, but only in one of 11 EL4 recipients of CD4-depleted A/J spleen cells evaluated (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Our previous studies showed that a single injection of 4,900 IU of IL-12 can significantly inhibit acute GVHD in a fully MHC plus multiple minor antigen-mismatched, A/J → B10 murine BMT model.21 The results of the present studies demonstrate that IL-12 preserves GVL effects against EL4 leukemia while delaying the onset of GVHD. Furthermore, the magnitude of the protective effect of IL-12 against GVHD is similar in leukemic mice as in IL-12–treated nonleukemic recipients (Fig 2). Despite the fact that IL-12 has been shown to promote antitumor immunity on its own,19,20 we did not observe any significant antileukemic effect of IL-12 in recipients of syngeneic spleen cells (Fig 1), indicating the limitation of syngeneic antitumor immunity in this model. As used in the model we have developed, EL4 appears not to be susceptible to the GVL effects of syngeneic T cells or NK cells even if these are activated by IL-12 or IL-2.11 Thus, measurable GVL effects in this model depend on the presence of alloreactive cells in the donor inoculum. It is well established that allogeneic T cells can mediate a GVL effect independently of GVHD,25,36-42 in some cases due to tissue specificity or tumor specificity of minor histocompatibility antigen expression.38,43-45 However, T cells responding to minor histocompatibility antigen exist at much lower frequency than those reacting to allogeneic MHC molecules, and anti-MHC responses can produce much more potent GVL responses than are observed in MHC-matched allogeneic BMT.46 This concept is supported by the present studies. The leukemic GVHD model used in the present study is a fully MHC plus multiple minor antigen-mismatched strain combination. The inability to detect EL4 cells by several assays in IL-12–treated, long-term surviving (more than 100 days) recipients of allogeneic BMC and spleen cells, suggests that the magnitude of GVL responses observed in IL-12–treated mice is sufficient to eradicate injected EL4 cells. Statistically significant inhibitory effects on GVHD and leukemia relapse were observed in IL-12–treated allogeneic EL4 recipients even when the tumor burden was increased by 1.5 logs.

Although IL-12 can enhance T-cell proliferation,47,48 a recent study has demonstrated that high doses of IL-12 administered to mice can lead to depletion of splenic CD4+ and CD8+ cells and can inhibit virus-specific CTL activity and CD8+ T cell expansion.49 We have recently demonstrated that the number of donor CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleens of IL-12–treated mice was markedly decreased in the first 4 days post-BMT in the GVHD model. However, donor CD8+ cells in all peripheral lymphoid tissues were subsequently increased on day 7 in IL-12–treated recipients compared with GVHD control mice.21 Previous studies showed that IL-12 plays a role in helper T-cell–independent, MHC I-primed cytotoxic T-lymphocyte generation, by a mechanism involving increased perforin and granzyme B gene expression.50 Acute GVHD has proved to be CD4-dependent in most fully MHC-plus multiple minor antigen-mismatched strain combinations examined, including the A/J → B10 combination studied here,12,51-55 and allogeneic CD8+ cells are the only mediators of GVL effects in this EL4 model.12 We therefore speculate that the IL-12–mediated early reduction of donor T cells and the delayed expansion of donor CD8+ T cells are responsible for the inhibition of GVHD and the preservation of GVL effects, respectively, in IL-12–treated mice. This hypothesis is supported by our observation of a GVL effect in IL-12–treated EL4-recipients that received CD4-depleted A/J spleen cells, but not in mice that received CD8-depleted or TCD A/J spleen cells (Fig 5). Thus, GVL effects against EL4 in IL-12–treated recipients of allogeneic spleen cells are CD8-dependent. CD4+ cells are not necessary for GVL effects in IL-12–treated or control mice, and NK cells do not appear to mediate significant antileukemic effects without CD8 cells in this model, even though IL-12 is administered. IL-12 has been shown to provide antitumor activity by inducing liver NK1.1+ cells in a murine model.20 However, another study showed that the antitumor activity of IL-12 is T (CD8)-dependent and NK cell-independent, as such activity was detected in both NK cell-deficient beige mice and in mice depleted of NK cells.19 In our model, although NK cells may play a role in GVL effects by inducing production of IFN-γ on day 2,21 they do not mediate significant antileukemic effects without CD8 cells, as GVL effects were undetectable in IL-12–treated mice receiving TCD allogeneic BMC and CD8-depleted spleen cells (Fig 5B). Recent studies have shown that IL-12 also induces significant protection against GVHD in the BALB/c → B6 strain combination, in which both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are involved in the induction of acute GVHD (our unpublished data). Strikingly, both subsets are also required for IL-12 protection to be observed. Studies are in progress to determine whether donor CD8+ T cells mediate GVL effects against EL4 leukemia in this strain combination.

Our previous studies have demonstrated that TCD syngeneic BMC can enhance, but are not required for, the protective effect of IL-12 against acute GVHD to be observed.21 Since TCD syngeneic BMC do not mediate detectable GVL effects in our model, the TCD B10 or B6 BMC are presumably not essential for the IL-12–mediated segregation of GVH and GVL effects by IL-12. This belief is supported by recent studies in a one MHC haplotype-mismatched murine BMT model, in which enhancement of CD8+ T-cell–mediated GVL effects was observed without increasing CD8+ T-cell–mediated GVHD in IL-12–treated recipients of allogeneic BMC and spleen cells without TCD syngeneic BMC (our unpublished data).

We have previously shown that a short course of high-dose IL-2, begun on the day of BMT, protects against GVHD in a fully MHC plus multiple minor antigen-mismatched BMT model. Unlike results in the IL-12 model described here, in which GVHD protection is associated with marked inhibition of early GVH-reactive donor Th expansion (B. Dey et al, manuscript submitted), no marked quantitative differences in the magnitude of GVH Th responses were observed in IL-2–treated allogeneic BMT recipients. Delayed kinetics of IFN-γ production were observed in association with the protective effect of IL-2 against GVHD.56 In contrast, an early surge in serum levels of IFN-γ is followed by complete inhibition of GVHD-associated IFN-γ production in IL-12–protected allogeneic recipients.21 Furthermore, GVHD protection in the IL-2 model is not dependent on IFN-γ,35 whereas the studies presented here have shown a clear dependence on IFN-γ release for the protective effect of IL-12. Therefore, IL-12 – and IL-2–induced GVHD-protection involve some differing mechanisms.

Previous reports on the role of IFN-γ in acute GVHD have been conflicting.35,57-62 Results of several murine tumor studies have suggested that IFN-γ is critical to IL-12–induced antitumor activity.19,63 In the GVHD model studied here, IL-12 treatment is associated with a marked increase in serum levels of IFN-γ on days 2 and 3, and this cytokine becomes almost undetectable on day 4 post-BMT, when serum IFN-γ peaks in untreated GVHD controls.21 Since exogenous IFN-γ has been previously shown to induce marked protection against GVHD62 and to have activity in vivo against tumors,64 we investigated the role of IFN-γ in the inhibition of GVHD and the generation of GVL responses in IL-12–treated mice. Results using a neutralizing rat antimouse IFN-γ MoAb suggest that the early increase in IFN-γ production induced by IL-12 treatment may play a role in the inhibitory effect of IL-12 against acute GVHD, as this effect was eliminated by giving anti–IFN-γ MoAb (Fig 3). Because this MoAb impaired the protective effect of IL-12 against GVHD, it was difficult to evaluate the contribution of IFN-γ to GVL effects by examining mortality. However, the timing of death and the clear evidence for leukemia at autopsy and histology in leukemic, anti–IFN-γ–treated allogeneic BMT recipients indicate that IFN-γ is involved in the GVL effect of allogeneic spleen cells against EL4 in IL-12–treated mice (Table 2, Fig 4). Therefore, the results presented here implicate a single molecule, IFN-γ, in both inhibiting GVHD and in the GVL effect of allogeneic spleen cells.

The data in this study demonstrate that allogeneic T cells can eradicate host leukemic cells, and that this antileukemic activity results partly from the activity of a cytokine that inhibits GVHD in IL-12–treated mice. Although, unlike EL4, human leukemias may also be susceptible to CD4-mediated GVL effects, in most experimental leukemia models, donor CD8+ T cells can mediate CD4-independent GVL effects, even when a CD4-mediated GVL effect also exists.13,65,66 The use of IL-12 differs from other approaches to inhibiting GVHD, such as T-cell depletion and nonspecific immunosuppressive drugs, which are associated with increased rates of leukemic relapse.4,5 67 Thus, the use of IL-12, perhaps in combination with other agents, may ultimately facilitate the performance of HLA-mismatched allogeneic BMT in leukemic patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Drs Henry Winn and Bimalangshu Dey for helpful discussion and review of the manuscript, and Dr David H. Sachs for his advice and encouragement. We also thank Yihong Sun, Tru Tran, and Guiling Zhao for outstanding animal care, and Diane Plemenos for expert assistance with the manuscript.

Supported by National Cancer Institute Grant No. R01 64912 and American Cancer Society Grant No. RPG-95-071-CIM.

Address reprint requests to Megan Sykes, MD, Transplantation Biology Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, MGH East, Bldg 149-5102, 13th St, Boston, MA 02129.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal