Abstract

Foals infected with equine infectious anemia virus become thrombocytopenic 7 to 20 days after virus inoculation, and within a few days following the onset of detectable viremia. The thrombocytopenia is associated with suppression of platelet production. Possible mediators of suppression of thrombopoiesis include tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), cytokines that are released during inflammation. To assess effects of plasma or serum from infected foals on megakaryocyte (MK) growth and maturation in vitro, equine low-density bone marrow cells were cultured for clonogenic and ploidy assays. Neutralizing antibodies to TNF-α and TGF-β were added to cultures to determine the contribution of these cytokines to suppression of thrombopoiesis. Plasma from the immediately pre-thrombocytopenia (Pre-Tp) period significantly reduced MK colony numbers. This suppression was partially reversed upon antibody neutralization of plasma TNF-α, TGF-β, or both. There were no differences in ploidy distribution of MK grown in the presence of preinfection serum compared with those grown in the presence of Pre-Tp serum. These results indicate that TNF-α and TGF-β may contribute to suppression of MK proliferation and represent likely factors in the pathogenesis of thrombocytopenia.

THROMBOCYTOPENIA is associated with a number of systemic viral infections and is well-documented in humans infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).1,2 In acute equine infectious anemia (EIA) caused by a related lentivirus, thrombocytopenia is a consistent clinical sign and has been found to follow within 2 to 4 days the initial onset of detectable viremia in experimentally infected horses.3,4 As with other lentiviral infections, viremia is persistent in EIA, but clinical signs of thrombocytopenia, fever, and anemia occur during irregular episodes of exuberant viral replication associated with emergence of antigenic neutralization escape variants.5 Platelet numbers typically return to normal promptly after viremia subsides.3 4

The pathogenesis of EIA virus (EIAV)-associated thrombocytopenia, like that associated with other lentiviruses, has not been well characterized. An increase in platelet-associated IgG and IgM in experimentally infected horses suggests an immune-mediated mechanism.3 However, the development of severe, progressive thrombocytopenia in all experimentally infected severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) foals, which lack functional T and B lymphocytes, indicates that non–immune-mediated mechanisms are also important and perhaps predominant.4 Platelet production during clinical episodes in both SCID foals and in immunocompetent foals is markedly reduced, although there is no apparent reduction in bone marrow megakaryocyte (MK) numbers6 and no evidence of virus in MK.3 4

The purpose of this study was to examine the role of potential negative regulators of platelet production on the growth and differentiation of equine MK in vitro. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) are factors with demonstrated suppressive effects on megakaryocytopoiesis in other species.7,8 Production of both of these factors is increased during some viral infections and as part of the acute inflammatory response.9-11 The principal cell of origin is the macrophage, which is the primary target cell of EIAV12,13 and which is present in normal numbers in SCID foals.14 Moreover, serum levels of both of these cytokines have been shown to be significantly increased in EIAV-infected foals in the days immediately preceding the onset of thrombocytopenia (Tornquist et al15 ).

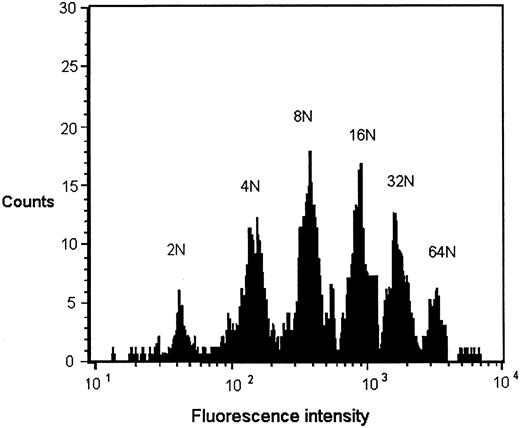

Decreased platelet production could be caused by reduced proliferation of early MK progenitor cells or by inhibition of MK maturation. Mature MK, typified by higher ploidies (16 N to 64 N) are capable of producing more platelets than immature MK.16 Clonogenic, or colony assays, and ploidy assays for evaluation of maturation were used in this study to determine if either decreased MK proliferation or decreased MK maturation contributed to reduced platelet production in EIA. Suppressive effects of serum or plasma-soluble factors from clinically ill foals and the contribution of TNF-α and TGF-β to that suppression were examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Horses, viruses, sampling.Six SCID and 10 immunocompetent foals were used in this study. With a single exception, the foals were housed in isolation, weaned at 4 weeks of age, and infected at 8 weeks of age. One immunocompetent foal was infected at 20 weeks of age. SCID foals were managed as previously described17 18 to minimize the likelihood of secondary infections.

Foals were infected intravenously with one of two strains of EIAV. All SCID foals and 2 immunocompetent foals were infected with EIAV-WSU5, a biologically cloned, fibroblast-adapted strain.19 Eight immunocompetent foals were infected with the Wyoming field strain EIAV-Wyo.

Foals were examined and body temperatures were taken daily. Blood was collected by jugular venipuncture daily. Complete blood counts were performed, and plasma and serum were separated promptly, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C. SCID foals were killed no later than day 3 after the first day of clinical thrombocytopenia T(0), defined as less than 151,000 platelets/μL. Immunocompetent foals were also euthanized within a few days of the onset of thrombocytopenia, except for 2 foals that were allowed to go through several cycles of clinical signs of viremia because they also were being used in other studies.

Platelet counts.Platelet counts were performed within 90 minutes of blood collection. Platelet counts for the first 9 foals were performed on platelet-rich plasma obtained from sodium citrate-collected blood and counted on a particle counter (Coulter Model ZBI-10; Coulter, Hialeah, FL), and the values were corrected to whole blood. Random samples were also counted in parallel on an automated cell counter (System 9000; Serono-Baker Diagnostics, Allentown, PA). The platelet counts were sufficiently similar that the automated cell counter was used for all platelet counts on the last 7 foals.

Detection of viremia.The level of infectious virus in the plasma of 11 of the foals was determined by fibroblast infectivity assay and reported elsewhere as part of a larger study on the thrombocytopenia of EIA.4 Viremia in all 16 foals was also assessed by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on serum samples taken from each foal before infection, in the immediate pre-thrombocytopenic (Pre-Tp) period, and on an intermediate day, 6 to 14 days before thrombocytopenia.

For RT-PCR, viral RNA was guanidinium thiocyanate, phenol, and chloroform-extracted from material pelleted from serum. The primer pair 5′-GCG CGA ATT CGG CTG GAA ACA GAA ATT TTA and 5′-GCG CGG ATC CTA GGT TTT CCA ATC ATC ACT was used to prime reverse transcription and to amplify a 448-bp segment of the p26 capsid protein gene of EIAV. The specificity of the assay for RNA was confirmed for positive samples by performing a duplicate reaction without reverse transcriptase.

Preparation of bone marrow cells.Bone marrow for culture was obtained from sternebrae of horses euthanized for nonfebrile, nonhematologic disorders at the Washington State University College of Veterinary Medicine Teaching Hospital. Immediately after euthanasia, marrow was collected aseptically into Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) with added 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL), gentamycin (50 μg/mL), amphotericin-B (2.5 μg/mL), and heparin (10 U/mL). Marrow was minced finely in medium, layered over Ficoll-Hypaque (Sigma Chemical Co, St Louis, MO), and centrifuged at 500g for 30 minutes at 18°C. Low-density marrow cells (LDMCs) at the interface were collected and washed twice by centrifugation at 700g for 15 minutes and resuspension in IMDM with serum and antibiotics, without heparin. After the second wash, cells were resuspended in medium and incubated in plastic petri dishes at 37°C for 2 hours to allow for macrophage adherence. Nonadherent cells were sedimented, resuspended in IMDM without serum, and counted. Viability of cells consistently exceeded 95% as determined by trypan blue exclusion.

Bone marrow culture.To optimize conditions for culture of equine MK colonies in agar clots and cell growth in liquid culture for ploidy determinations, a variety of cell concentrations, growth factor sources, additives, and incubation periods were evaluated. Recombinant human interleukin-3 (rhIL-3), rhIL-6, and recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (rhGM-CSF; R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were tested at a range of concentrations. Fetal equine serum (Sigma Chemical Co) and plasma from a single normal mare were aliquoted, stored at −20°C, and evaluated at concentrations of 10%, 15%, 20%, and 25% in the final culture medium. As a source of equine growth factors, medium conditioned on equine cells was prepared by culture of Ficoll-Hypaque-separated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Washed cells were resuspended at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL in Dulbecco's Modified Essential Medium, 10% FCS, and 1% pokeweed mitogen (Sigma). Cultures were incubated at 37°C for 5 days, and the medium was harvested, clarified, aliquoted, and stored at −20°C. Recombinant human megakaryocyte growth and development factor (rhMGDF; a generous gift from Amgen Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA) was tested at concentrations of 12.5, 25, 50, 125, and 250 ng/mL for effects on growth of equine MK.

Megakaryocyte colony assays.After optimal equine MK growth conditions were determined, colony assays were performed with the following components present in every culture: 1 × 105 cells in 1 mL of IMDM supplemented with 50 μmol/L β-mercaptoethanol, penicillin-streptomycin, 125 ng rhMGDF, and 10% equine cell-conditioned media. The variable component in each set of replicate cultures was the source of the 15% equine plasma that was added. Within a set of assays performed at one time, triplicate cultures received plasma from either the normal mare, a preinfection foal, or from the same foal 2 or 3 days before it became thrombocytopenic (Pre-Tp). In addition, replicate assays also received Pre-Tp plasma that had been preincubated with (1) a neutralizing antiequine TNF-α monoclonal antibody,20,21 (2) a pan-specific anti–TGF-β polyclonal neutralizing antibody (R & D Systems), or (3) both anti–TNF-α and anti–TGF-β. Neutralization of equine plasma TNF-α and TGF-β activity using these antibodies had been previously shown by complete abolition of detectable activity in bioassays (Tornquist et al15 ). Controls included the following: normal mare plasma preincubated with anti–TNF-α, anti–TGF-β, or both; preinfection foal plasma preincubated with anti–TNF-α, anti–TGF-β, or both; and Pre-Tp plasma preincubated with an isotype-matched monoclonal antibody (anti–TNF-α control), antisera of irrelevant specificity (anti–TGF-β control), or both. Cultures were performed in triplicate in 35-mm dishes (Corning Inc, Corning, NY) and rendered semisolid by the addition of 0.3% agar and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 7 days. MK colonies, defined as aggregates of at least 3 cells, were counted using an inverted microscope.

Identification of MK colonies in cultures was facilitated by detection of von Willebrand factor. Agar clots were fixed in 2% formalin and rinsed. Endogenous peroxidases were blocked by treatment with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide and 0.1% azide. Nonspecific staining was reduced by preincubation with 5% normal goat serum. Clots were incubated with rabbit antiserum to human von Willebrand factor (Dako, Carpinteria, CA), followed by biotinylated goat antirabbit antibody and avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Treatment with 0.05% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Vector Laboratories) was followed by rinsing and counting of brown-staining colonies. Specificity of staining was initially determined by incubating control cultures with normal rabbit Ig fraction (Dako) instead of the primary antibody.

To determine whether infectious EIAV in plasma would affect MK colony numbers, assays were included in which 1 × 106 TCID50 of EIAV-WSU5 were added to cultures. In addition, aliquots of Pre-Tp foal plasma were divided and half of each aliquot was centrifuged at 47,000g for 1 hour to sediment virus. Centrifuged and uncentrifuged supernatants were added to cultures, and MK colony numbers were compared.

Analysis of megakaryocyte ploidy from suspension cultures.LDMCs were cultured in 12-well culture plates at a concentration of 1 to 2 × 106 cells/mL in IMDM containing the growth factors and antibiotics described above. Normal mare serum, preinfection foal serum, or Pre-Tp foal serum to give a final 15% concentration was added to replicate cultures. Other cultures received normal mare, preinfection, or Pre-Tp serum that had been preincubated with neutralizing antibody against TNF-α, TGF-β, or both. Control cultures included Pre-Tp foal serum preincubated with either an isotype-matched irrelevant monoclonal antibody (anti–TNF-α control), an irrelevant antisera (anti–TGF-β control), or both. Cell numbers and morphology were monitored by examination of cytocentrifuged preparations every few days.

After 10 days of incubation, cells were harvested and prepared for flow cytometric analysis of ploidy. Cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.5% bovine serum albumin and incubated with 15 μg/mL of a murine monoclonal anti-glycoprotein IIbIIIa (a generous gift from Dr Thomas Kunicki, Milwaukee, WI) or an isotype-matched control. After three washes, the cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat-antimouse Ig (Caltag Laboratories, San Francisco, CA), washed, and resuspended in a solution of 0.1% sodium citrate, 30 μg/mL DNAse-free RNAse (GIBCO BRL, Gathersburg, MD), 50 μg/mL propidium iodide, and 0.1% Triton X-100. After incubation for 20 minutes at room temperature, the cells were analyzed on a FACSort flow cytometer using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). A gate was set to exclude 98% of the cells labeled with the isotype control antibody. The ploidy distribution of the anti-GPIIbIIIa–labeled cells was determined by setting markers at the nadirs between propidium iodide peaks. The 2 N peak position was defined by setting markers at the peak of propidium iodide staining of normal horse PBMCs. Between 2 × 103 and 3 × 103 megakaryocytes were analyzed from each culture, and the percentage of cells in each of five ploidy classes was calculated.

Statistical analysis.Analysis of both the colony number and ploidy data were performed by analysis of variance based on a split-plot experimental design. Fisher's least significant difference for multiple comparison of means was used to determine differences between SCID and immunocompetent foals and differences between treatments (SAS software; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).22 A P value of <.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Platelet counts.Platelet levels of less than 151,000/μL were considered thrombocytopenic based on a normal platelet count range (151,000 to 437,000/μL) established for age-matched uninfected Arabian foals. As previously described, there were no significant differences between platelet counts of uninfected SCID foals and uninfected immunocompetent foals at similar ages.4

All foals became thrombocytopenic between 7 and 20 days postinfection. SCID and immunocompetent foals differed with respect to onset of thrombocytopenia, with immunocompetent foals becoming thrombocytopenic earlier (mean, 10.1 dpi; range, 7 to 13 dpi) than SCID foals (mean, 18.5 dpi; range, 16 to 20 dpi). The platelet count in SCID foals continued to decrease until the day of euthanasia. We had previously shown that platelet counts in SCID foals progressively and sharply decreased until death or euthanasia at platelet counts of less than 30,000/ μL.4 For this study, therefore, SCID foals were euthanized once the onset of thrombocytopenia had been clearly established and before clinical signs of marked depression and anorexia developed. Platelet counts in immunocompetent foals typically rebound to normal levels within 3 to 5 days of a decrease in viremia.4 In the present study, 8 of 10 immunocompetent foals were killed during the first cycle of clinical signs and viremia; platelet counts in these foals ranged from 14,297/μL to 28,771/μL at the time of euthanasia. Two immunocompetent foals reached nadirs of 52,464 platelets/μL and 39,111 platelets/μL before clinical signs of EIA resolved and platelet counts returned to normal levels.

Viremia.Virus was detected by RT-PCR in all sera taken from foals 1 to 3 days before they became thrombocytopenic, but none of the preinfection sera. On the intermediate day, only a single SCID foal serum contained detectable viral RNA, 6 days before thrombocytopenia. These findings were consistent with earlier reports of viremia as measured by fibroblast infectivity assay4 and serum reverse transcriptase assay.3

Culture conditions.Growth of MK colonies was generally poor with recombinant human growth factors IL-3, IL-6, and GM-CSF at several different concentrations and commercial fetal equine serum. Substitution of 15% equine cell-conditioned media and 15% plasma from a normal mare improved colony numbers. Inclusion of 125 ng/mL rhMGDF further increased colony numbers approximately 2.5-fold. Additional rhMGDF was of no benefit. MK colony numbers plateaued after 7 days of incubation.

MK growth in liquid culture was monitored by examination of cytocentrifuged cells every 1 to 2 days. Concentrations of factors proven optimal in semisolid cultures resulted in good numbers and morphology of MKs in liquid cultures. MK numbers reached a maximum at 10 days of culture.

Megakaryocyte colony numbers.Pre-Tp plasma significantly lowered the mean MK colony number per culture (7.98 ± 2.62) as compared with cultures receiving preinfection plasma (27.46 ± 2.44; P = .0001). This suppression of colony number was partially reversed by neutralization of TGF-β (14.71 ± 2.83) and to a somewhat lesser extent by neutralization of TNF-α (12.65 ± 2.95). Neutralization with the combination of anti–TGF-β and anti–TNF-α antibodies resulted in a mean colony number (15.22 ± 0.81) that was not significantly different from that obtained by neutralization of TGF-β alone (Table 1). Addition of anti–TNF-α or anti–TGF-β antibodies to normal mare and preinfection foal plasma produced no significant changes in MK colony numbers.

Effect of Pre-Tp Plasma and Neutralization of Cytokines on MK Colony Growth

| Plasma Added . | No. of MK Colonies per Culture . |

|---|---|

| Normal mare plasma | 26.7 ± 1.9* |

| Preinfection | 27.5 ± 2.5* |

| Preinfection + anti–TGF-β | 26.8 ± 1.8* |

| Preinfection + anti–TNF-α | 27.9 ± 2.5* |

| Preinfection + anti–TGF-β and anti–TNF-α | 25.9 ± 3.0* |

| Pre-Tp | 8.0 ± 2.6† |

| Pre-Tp + anti–TGF-β | 14.6 ± 2.7‡ |

| Pre-Tp + anti–TNF-α | 12.8 ± 2.9 |

| Pre-Tp + anti–TGF-β and anti–TNF-α | 15.2 ± 0.8‡ |

| Pre-Tp + antibody control | 8.3 ± 2.9† |

| Plasma Added . | No. of MK Colonies per Culture . |

|---|---|

| Normal mare plasma | 26.7 ± 1.9* |

| Preinfection | 27.5 ± 2.5* |

| Preinfection + anti–TGF-β | 26.8 ± 1.8* |

| Preinfection + anti–TNF-α | 27.9 ± 2.5* |

| Preinfection + anti–TGF-β and anti–TNF-α | 25.9 ± 3.0* |

| Pre-Tp | 8.0 ± 2.6† |

| Pre-Tp + anti–TGF-β | 14.6 ± 2.7‡ |

| Pre-Tp + anti–TNF-α | 12.8 ± 2.9 |

| Pre-Tp + anti–TGF-β and anti–TNF-α | 15.2 ± 0.8‡ |

| Pre-Tp + antibody control | 8.3 ± 2.9† |

Equine marrow cells were cultured in triplicate in agar clots and MK colonies were counted on day 7. Mean MK colony number is expressed per 1 × 105 cells plated. The data shown are the mean values for 16 foals. SCID and immunocompetent foal values were not statistically different; thus, data were pooled. Colony numbers were not significantly different using the two antibody controls (murine isotype-matched monoclonal and rabbit polyclonal antiserum) separately or in combination, so the antibody control category is a pooled value. Differences between means were statistically significant (P < .05), except where noted.

No significant difference between these means.

No significant difference between these means.

No significant difference between these means.

There were no significant differences between MK colony numbers in cultures to which SCID and immunocompetent foal plasma of comparable infection status were added. No differences in colony numbers were found when EIAV was added to cultures or when virus was pelleted out of test samples before addition to assays (data not shown).

Megakaryocyte ploidy.Cultured bone marrow cells expressing glycoprotein IIbIIIa were divided into ploidy classes from 2 N to 32 N by DNA content as determined by histogram distributions of intensity of propidium iodide staining (Fig 1). The position of the 2 N peak in each flow cytometric analysis was determined by propidium iodide staining of normal equine PBMCs at the time of analysis. Modal ploidy in each case was 8 N. Ploidy distribution of cultures receiving preinfection serum and those receiving Pre-Tp serum were not significantly different. Neutralization of Pre-Tp sera with anti–TGF-β, with anti–TNF-α, and with both antibodies similarly had no effect on ploidy distribution (Table 2). There were no significant differences in MK ploidy when SCID or immunocompetent foal sera were added to cultures.

Representative DNA histogram of GPIIbIIIa-positive cells grown in liquid culture. Equine low-density marrow cells were cultured in the presence of Pre-Tp foal serum, labeled with an anti-GPIIbIIIa antibody, stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The position of the 2 N peak was determined by setting markers for peak propidium iodide staining of PBMCs from a normal horse. Three thousand GPIIbIIIa-positive cells were analyzed. Ploidy distribution is similar to that obtained in MK cultures exposed to preinfection serum and normal horse serum.

Representative DNA histogram of GPIIbIIIa-positive cells grown in liquid culture. Equine low-density marrow cells were cultured in the presence of Pre-Tp foal serum, labeled with an anti-GPIIbIIIa antibody, stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The position of the 2 N peak was determined by setting markers for peak propidium iodide staining of PBMCs from a normal horse. Three thousand GPIIbIIIa-positive cells were analyzed. Ploidy distribution is similar to that obtained in MK cultures exposed to preinfection serum and normal horse serum.

Effect of Pre-Tp Serum and Neutralization of Cytokines on MK Ploidy Distribution

| Serum Added . | Percentage of MK in Each Ploidy Class . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 2 N . | 4 N . | 8 N . | 16 N . | 32 N . | 64 N . |

| Normal mare | 3.56 ± 6.2 | 14.21 ± 3.5 | 24.66 ± 5.8 | 20.48 ± 4.9 | 10.58 ± 4.4 | 2.97 ± 0.9 |

| Preinfection | 3.83 ± 2.5 | 15.11 ± 5.8 | 23.81 ± 9.2 | 19.24 ± 6.0 | 11.53 ± 5.6 | 2.38 ± 1.2 |

| Preinfection + anti–TGF-β | 4.97 ± 4.7 | 13.89 ± 5.5 | 25.03 ± 7.1 | 18.68 ± 4.7 | 12.24 ± 5.3 | 3.01 ± 0.8 |

| Preinfection + anti–TNF-α | 3.75 ± 5.2 | 15.28 ± 3.7 | 23.52 ± 6.6 | 20.34 ± 5.2 | 10.75 ± 4.9 | 2.34 ± 1.7 |

| Preinfection + anti–TGF-β and anti–TNF-α | 4.02 ± 3.6 | 14.25 ± 4.3 | 24.66 ± 5.8 | 22.56 ± 5.5 | 11.89 ± 4.5 | 2.74 ± 1.9 |

| Pre-Tp | 3.14 ± 2.0 | 14.39 ± 5.4 | 22.91 ± 9.4 | 18.98 ± 6.7 | 11.03 ± 5.7 | 2.78 ± 2.1 |

| Pre-Tp + anti–TGF-β | 4.30 ± 2.8 | 15.77 ± 6.1 | 24.86 ± 8.2 | 19.81 ± 5.7 | 10.64 ± 4.1 | 2.09 ± 1.5 |

| Pre-Tp + anti–TNF-α | 4.76 ± 1.0 | 14.14 ± 2.7 | 23.97 ± 3.6 | 24.10 ± 5.0 | 10.69 ± 4.1 | 2.03 ± 0.6 |

| Pre-Tp + anti–TGF-β and TNF-α | 5.01 ± 3.1 | 15.04 ± 5.6 | 23.09 ± 7.8 | 21.55 ± 5.2 | 12.47 ± 4.8 | 2.41 ± 1.1 |

| Pre-Tp + antibody control | 3.76 ± 6.1 | 15.38 ± 5.9 | 22.79 ± 6.5 | 23.69 ± 5.8 | 12.58 ± 5.3 | 2.66 ± 2.0 |

| Serum Added . | Percentage of MK in Each Ploidy Class . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 2 N . | 4 N . | 8 N . | 16 N . | 32 N . | 64 N . |

| Normal mare | 3.56 ± 6.2 | 14.21 ± 3.5 | 24.66 ± 5.8 | 20.48 ± 4.9 | 10.58 ± 4.4 | 2.97 ± 0.9 |

| Preinfection | 3.83 ± 2.5 | 15.11 ± 5.8 | 23.81 ± 9.2 | 19.24 ± 6.0 | 11.53 ± 5.6 | 2.38 ± 1.2 |

| Preinfection + anti–TGF-β | 4.97 ± 4.7 | 13.89 ± 5.5 | 25.03 ± 7.1 | 18.68 ± 4.7 | 12.24 ± 5.3 | 3.01 ± 0.8 |

| Preinfection + anti–TNF-α | 3.75 ± 5.2 | 15.28 ± 3.7 | 23.52 ± 6.6 | 20.34 ± 5.2 | 10.75 ± 4.9 | 2.34 ± 1.7 |

| Preinfection + anti–TGF-β and anti–TNF-α | 4.02 ± 3.6 | 14.25 ± 4.3 | 24.66 ± 5.8 | 22.56 ± 5.5 | 11.89 ± 4.5 | 2.74 ± 1.9 |

| Pre-Tp | 3.14 ± 2.0 | 14.39 ± 5.4 | 22.91 ± 9.4 | 18.98 ± 6.7 | 11.03 ± 5.7 | 2.78 ± 2.1 |

| Pre-Tp + anti–TGF-β | 4.30 ± 2.8 | 15.77 ± 6.1 | 24.86 ± 8.2 | 19.81 ± 5.7 | 10.64 ± 4.1 | 2.09 ± 1.5 |

| Pre-Tp + anti–TNF-α | 4.76 ± 1.0 | 14.14 ± 2.7 | 23.97 ± 3.6 | 24.10 ± 5.0 | 10.69 ± 4.1 | 2.03 ± 0.6 |

| Pre-Tp + anti–TGF-β and TNF-α | 5.01 ± 3.1 | 15.04 ± 5.6 | 23.09 ± 7.8 | 21.55 ± 5.2 | 12.47 ± 4.8 | 2.41 ± 1.1 |

| Pre-Tp + antibody control | 3.76 ± 6.1 | 15.38 ± 5.9 | 22.79 ± 6.5 | 23.69 ± 5.8 | 12.58 ± 5.3 | 2.66 ± 2.0 |

Equine marrow cells were grown in liquid culture and prepared for ploidy analysis on day 10. Cells were labeled with a murine anti-GPIIbIIIa monoclonal antibody and propidium iodide and analyzed by flow cytometry. Between 2,000 and 3,000 MK were analyzed. Data shown are means from 16 foals, with triplicate cultures for each treatment. There were no significant ploidy distribution differences between cultures grown in the presence of preinfection or Pre-Tp serum. The antibody control category is pooled data from cultures receiving both antibody controls (murine isotype-matched monoclonal antibody and rabbit polyclonal antiserum) separately and in combination.

DISCUSSION

Causes of virus-induced thrombocytopenia have been studied in many viral infections and are most often ascribed to either immune-mediated platelet destruction or direct infection of the MK.3,23,25 The opportunity to examine a reproducible model of development of thrombocytopenia after experimental viral infection in both immunocompetent and immunodeficient foals has led us to conclude that other factors contribute substantively to thrombocytopenia in EIA. Previous studies in this laboratory showed a marked reduction in platelet production in both SCID and immunocompetent foals, with no evidence of MK infection or decrease in MK number.4,6 These results parallel those of Ballem et al,1 who reported decreased platelet production in HIV infection, and those of Clabough et al,3 who found no evidence of EIAV in MK from infected, thrombocytopenic horses.

We hypothesized that negative regulation of platelet production during acute EIA could be mediated in part by factors released by macrophages in response to viral infection. Evidence for suppression of hematopoiesis by infection of nonhematopoietic cells in the bone marrow has been found for a variety of viruses, including HIV,8,26,28 simian immunodeficiency virus,10,29 feline immunodeficiency virus,30 feline leukemia virus,31,32 human herpesvirus-6,33,34 and cytomegalovirus.35 Viral infection of nonhematopoietic cells could suppress hematopoiesis either by inhibiting production of stimulatory factors or by increasing production of inhibitors. Infected cells in the bone marrow may release factors with autocrine or paracrine effects, and there is also evidence that elevated levels of circulating factors suppress hematopoiesis in an endocrine manner.7,9 36-38

The results of the present study show that, during clinical episodes of EIA, circulating factors are present that can suppress proliferation of MK colonies by more than threefold but that have no apparent effect on MK ploidy. Approximately 35% of the suppression could be reversed by neutralization of TNF-α and TGF-β, suggesting that a substantial portion of suppression in this disease is due to other mechanisms. This is not surprising, given the complexity of regulation of MK proliferation and maturation.

TNF-α, which is produced primarily by activated macrophages, is elevated in serum and bone marrow of acutely ill foals (Tornquist et al15 ) and may contribute to the development of some clinical signs in EIA such as fever, anorexia, and depression.39 TNF-α reduces MK colony numbers in vitro.40,41 Administration of TNF-α is associated with the development of thrombocytopenia in humans36,42 and mice.37

TGF-β, a cytokine that can either stimulate or suppress growth depending on its concentration, the target cell type, and presence of other factors, is produced in active form primarily by macrophages.43 Levels of TGF-β are elevated during acute EIA episodes (Tornquist et al15 ), because they are in some other systemic viral infections.44-46 TGF-β suppresses colony growth both directly, by addition of purified TGF-β to cultures,47 and by abrogation of colony inhibition by neutralization of TGF-β released by stimulated macrophages.48 Serum from patients in the acute and clinical remission phases of thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura (TTP) suppresses MK colony numbers in both autologous and normal bone marrow hematopoietic cell cultures.49 As in the present study, neutralization of TGF-β in the serum from TTP patients significantly reduced MK colony inhibition.

TGF-β inhibited MK endomitosis in an immortalized human MK cell line and in a rat bone marrow culture system.50 51 Therefore, it was somewhat surprising to find no detectable effect of serum containing TGF-β on MK differentiation, as measured by ploidy distribution in this study. It is unlikely that horses differ from other species in the effects of TGF-β on MK differentiation. There are several other possible explanations for the absence of a detectable shift in MK ploidy given the conditions used in this study. Foal sera were added to the MK cultures only at the beginning of the 10-day culture period. Presuming that no active TGF-β would be produced in the cultures, the exposure of the developing MK to TGF-β in foal sera may have been of insufficient duration to produce any detectable inhibitory effects. Secondly, the standard level of thrombopoietin added to all cultures may have been a more important determinant of ploidy than the varied levels of TGF-β and TNF-α in sera from infected foals. To further examine MK differentiation in foals with clinical EIA, it would be useful to measure MK ploidy on noncultured bone marrow cells obtained from infected foals before and during the development of thrombocytopenia to determine whether detectable ploidy changes occur in vivo.

Our data fail to support additive or synergistic suppressive effects between TNF-α and TGF-β on MK colony numbers. Although neutralization of both factors resulted in a slightly higher mean colony number than neutralization of either factor alone, the difference was not statistically significant.

The addition of infectious virus to cultures of MK progenitors did not lead to suppression of MK colony formation, which contrasts with an earlier study of the effects of EIAV on erythroid progenitor cells in vitro.52 That study reported that EIAV significantly reduced formation of erythroid colonies in cultures of equine bone marrow mononuclear cells. Because the marrow cell preparations were not depleted of macrophages in that study, it is possible that EIAV replication in the macrophages in the cultures may have stimulated release of soluble factors inhibiting erythropoiesis. Thus, indirect suppression of hematopoietic progenitor cells by factors induced by viral replication could be common to both anemia and thrombocytopenia of EIA. We did not evaluate erythroid and myeloid progenitors in this study. Although viral replication-induced cytokines undoubtedly affect these other hematopoietic lineages, anemia and leukopenia are much less consistent hematologic findings in acute EIA than is thrombocytopenia.

There were no significant differences in the effects of SCID and immunocompetent foal serum and plasma on MK colony number and ploidy. This is consistent with the fact that in vivo platelet counts of uninfected SCID foals are no different from those of age-matched immunocompetent foals.4 TNF-α and TGF-β both increase during clinical disease episodes in SCID as well as immunocompetent foals (Tornquist et al15 ).

The use of EIAV-infected horses as a model for lentivirus-induced thrombocytopenia has proven useful in dissecting the highly complex pathogenetic mechanisms of the phenomenon. Cytokines circulating during acute EIA suppress MK progenitor proliferation, potentially contributing to decreased platelet production. Other factors also clearly play a role in reduction of MK colony growth, and future investigations using this model could further clarify the regulation of megakaryocytopoiesis in systemic viral disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr V. Broudy and N. Lin (University of Washington, Seattle, WA) for help with megakaryocyte assay techniques; Amgen, Inc (Thousand Oaks, CA) for the gift of MGDF; Drs J. Cargile and R. MacKay (University of Florida, Gainesville, FL) for antiequine TNF-α monoclonal antibody; and Dr J.L. Oaks for assistance with the RT-PCR viral assays.

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant No. R01-HL46551, Washington State University Equine Research Program Project 0079, and Public Health Services Pathobiology Training Grant No. T32-AI07367.

Address reprint requests to Susan J. Tornquist, DVM, PhD, College of Veterinary Medicine, Magruder Hall, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331-4802.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal