Abstract

We have shown previously that the Rhesus (Rh) polypeptides are the commonest targets for pathogenic anti-red blood cell (RBC) autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA). The aim of the current work was to determine whether activated T cells from such patients also mount recall responses to epitopes on these proteins. Two panels of overlapping 15-mer peptides, corresponding to the sequences of the 30-kD Rh proteins associated with expression of the D and Cc/Ee blood group antigens, were synthesized and screened for the ability to stimulate the in vitro proliferation of mononuclear cells from the peripheral blood or spleen of nine AIHA cases. Culture conditions were chosen that favor recall proliferation by previously activated T cells, rather than primary responses. In seven of the patients, including all four cases with autoantibody to the Rh proteins, two or more peptides elicited proliferation, but cells from eight of nine patients with other anemias and seven of nine healthy donors failed to respond to the panels. Multiple peptides were also stimulatory in two positive control donors who had been alloimmunized with Rh D-positive RBCs. Six different profiles of peptides elicited responses in the AIHA patients, and this variation may reflect the different HLA types in the group. Stimulatory peptides were identified throughout domains shared between, or specific to, each of the related 30-kD Rh proteins, but T cells that responded to nonconserved regions did not cross-react with the alternative sequences. Anti-major histocompatibility complex class II antibodies blocked the responses and depletion experiments confirmed that the proliferating mononuclear cells were T cells. Notably, splenic T cells that proliferated against multiple Rh peptides also responded to intact RBCs. We propose that pathogenic autoantibody production in many cases of AIHA is driven by the activation of T-helper cells specific for previously cryptic epitopes on the Rh proteins.

CURRENT MEDICAL treatments for autoimmune diseases are unsatisfactory, because therapy is largely restricted to the use of immunosuppressive or anti-inflammatory agents, which are merely palliative while causing potentially serious toxic effects. However, novel forms of immunotherapy have recently been described in rodent models of autoimmune disease. For example, the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis may be inhibited by administration of synthetic peptides corresponding to autoantigenic epitopes, or epitope analogues, recognized by pathogenic T cells.1-3 Such an approach may provide an alternative strategy for effective, specific treatment of human autoimmune conditions.

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) was one of the first diseases that was shown to have an autoimmune pathology4 and remains one of the few such conditions in which important target antigens have been identified in humans. We have previously shown, using both immunoprecipitation and serological methods, that the antigens recognized by pathogenic autoantibodies in AIHA can vary between different cases, but that one pattern of specificity predominates.5 The apparent molecular mass of the most commonly precipitated autoantigens indicates that they are polypeptides from the Rhesus (Rh) complex of red blood cells (RBCs). The identification of the Rh polypeptides as targets for pathogenic autoantibodies is supported by the results of previous serological studies6 and has been subsequently confirmed by others using immunoprecipitation techniques.7

Antibody responses to the vast majority of antigens are T-cell dependent, and the production of anti-RBC autoantibodies appears to be no exception. Thus, treatment with anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody (MoAb) abrogates spontaneous autoantibody production in NZB mice8 and prevents murine AIHA induced by inoculation with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus.9 Furthermore, T-cell depletion protects mice from developing the AIHA that follows repeated immunization with rat RBCs,10 and we have also recently reported the activation of RBC-reactive T cells in the peripheral blood of a dog with spontaneous AIHA.11 It would therefore be predicted that human patients with AIHA would also harbor activated helper T cells responsive to RBC autoantigens and that such lymphocytes would recognize epitopes on the Rh proteins in cases with Rh-specific autoantibody.

The amino acid sequences of the two 30-kD Rh polypeptides associated with the expression of the D12,13 and Cc/Ee14 15 blood group antigens have recently been deduced from cDNA analyses, making it possible to identify autoreactive T-cell epitopes on these proteins. Before the potential for peptide immunotherapy can be evaluated in human AIHA, it is clearly necessary to map T-cell determinants on the relevant autoantigens. The aim of the current work was therefore to identify any epitopes on the Rh polypeptides that stimulate recall responses in vitro by T cells obtained from a series of patients with AIHA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples.AIHA was diagnosed in a series of patients attending the Bristol Royal Infirmary and Aberdeen Royal Hospital on the basis of clinical and hematologic investigation and a positive Coombs' test result. Details of the cases are summarized in Table 1. At presentation, each patient had low hemoglobin levels, spherocytosis, an increased reticulocyte count, and an elevated bilirubin level, and all cases responded to corticosteroid treatment, apart from one individual who died from fulminant hemolysis after 1 week. Patients were only included in the series if they were considered to have primary AIHA with no evidence of underlying disease. Note that, with the exception of case no. 4, who was a D-negative individual, the RBCs of all patients expressed both the Cc/Ee and D Rh proteins. In one patient undergoing splenectomy, splenic tissue was obtained under aseptic conditions, and blood samples from the remaining cases were collected by venupuncture into citrate or heparin anticoagulant for cell culture or plain glass tubes for serum separation (Vacutainer; Becton Dickinson, Cowley, Oxon, UK). Leukocyte concentrates from healthy human volunteers with no serological evidence of anti-D alloantibodies and from Rh D-negative donors alloimmunized with Rh D-positive RBCs were obtained from the Regional Transfusion Centre (Bristol, UK).

Details of AIHA-Positive Cases

| Case No. . | Age (yr)/Sex . | Rh Type . | Samples . | Treatment . | Hemoglobin . | Reticulocytes . | Coombs' Test . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | Obtained . | at Sampling . | (g/dL) . | (%) . | . |

| 1 | 19/F | CDe/CDe | Splenic tissue | Prednisolone | 3.3 | 90 | IgG+++ |

| 2 | 59/M | CDe/cde | Peripheral blood | None | 2.8 | 20 | IgG+++ |

| 3 | 62/F | CDe/cDE | Peripheral blood | Prednisolone | 11.2 | 1.9 | IgG+++ |

| 4 | 83/F | cde/cde | Peripheral blood | None | 6.9 | 17 | IgG+++ |

| 5 | 69/F | CDe/cde | Peripheral blood | Prednisolone | 6.8 | 10 | IgG++ |

| 6 | 59/F | D positive | Peripheral blood | Prednisolone | 10.0 | Not recorded | IgG+++ |

| 7 | 70/M | cDe/cde | Peripheral blood | None | 6.2 | 16 | IgG++ |

| 8 | 50/M | CDe/cde | Peripheral blood | None | 4.7 | 15 | IgG+++ |

| 9 | 78/F | cDE/cde | Peripheral blood | Prednisolone | 4.8 | 22 | IgG+++ |

| Case No. . | Age (yr)/Sex . | Rh Type . | Samples . | Treatment . | Hemoglobin . | Reticulocytes . | Coombs' Test . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | Obtained . | at Sampling . | (g/dL) . | (%) . | . |

| 1 | 19/F | CDe/CDe | Splenic tissue | Prednisolone | 3.3 | 90 | IgG+++ |

| 2 | 59/M | CDe/cde | Peripheral blood | None | 2.8 | 20 | IgG+++ |

| 3 | 62/F | CDe/cDE | Peripheral blood | Prednisolone | 11.2 | 1.9 | IgG+++ |

| 4 | 83/F | cde/cde | Peripheral blood | None | 6.9 | 17 | IgG+++ |

| 5 | 69/F | CDe/cde | Peripheral blood | Prednisolone | 6.8 | 10 | IgG++ |

| 6 | 59/F | D positive | Peripheral blood | Prednisolone | 10.0 | Not recorded | IgG+++ |

| 7 | 70/M | cDe/cde | Peripheral blood | None | 6.2 | 16 | IgG++ |

| 8 | 50/M | CDe/cde | Peripheral blood | None | 4.7 | 15 | IgG+++ |

| 9 | 78/F | cDE/cde | Peripheral blood | Prednisolone | 4.8 | 22 | IgG+++ |

Summary of Rh Peptides Stimulating MC From AIHA Patients In Vitro

| Case No. . | Synthetic Rh D or Cc/Ee Peptides Stimulating Proliferation (SI > 3) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| . | D-Specific . | Cc/Ee-Specific . | Cc/Ee and D Shared . |

| 1 | 6, 7, 10*, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 40 | 36 | 3, 4, 8, 9, 37, 39 |

| 2 | Not tested† | 6, 10, 15*, 19, 23, 26 | None |

| 3 | 19, 25, 31 | 12 | 1, 29* |

| 4 | None | 13* | 2 |

| 5 | None | 13 | 2* |

| 6 | None | Not tested | 1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 14, 21, 29*, 38 |

| 7 | 19, 22, 31 | 30, 32 | 28* |

| 8 | None | None | None |

| 9 | None | None | None |

| Case No. . | Synthetic Rh D or Cc/Ee Peptides Stimulating Proliferation (SI > 3) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| . | D-Specific . | Cc/Ee-Specific . | Cc/Ee and D Shared . |

| 1 | 6, 7, 10*, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 40 | 36 | 3, 4, 8, 9, 37, 39 |

| 2 | Not tested† | 6, 10, 15*, 19, 23, 26 | None |

| 3 | 19, 25, 31 | 12 | 1, 29* |

| 4 | None | 13* | 2 |

| 5 | None | 13 | 2* |

| 6 | None | Not tested | 1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 14, 21, 29*, 38 |

| 7 | 19, 22, 31 | 30, 32 | 28* |

| 8 | None | None | None |

| 9 | None | None | None |

Peptide eliciting greatest proliferation.

Patient died before the panel of D peptides was tested.

Sequences and Predicted Topography of Stimulatory Rh Peptides

| Stimulatory Peptide . | Responding Case Nos. . | Sequence . | Predicted Topography3-150 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-specific | |||

| 6 | 1 | QDLTVMAAIGLGFLT | Transmembrane |

| 7 | 1 | LGFLTSSFRRHSWSS | Transmembrane |

| 10 | 1 | ILLDGFLSQFPSGKV | Extracellular |

| 11 | 1 | PSGKVVITLFSIRLA | Extracellular |

| 12 | 1 | SIRLATMSALSVLIS | Transmembrane |

| 13 | 1 | SVLISSVDAVLGKVNL | Transmembrane |

| 15 | 1 | MVLVEVTALGNLRMV | Transmembrane |

| 16 | 1 | NLRMVISNIFNTDYH | Extracellular |

| 19 | 3, 7 | SVAWCLPKPLPEGTE | Intracellular |

| 22 | 1, 7 | GALFLWIFWPSFNSA | Transmembrane |

| 23 | 1 | SFNSALLRSPIERKN | Extracellular |

| 24 | 1 | IERKNAVFNTYYAVA | Transmembrane |

| 25 | 1, 3 | YYAVAVSVVTAISGS | Transmembrane |

| 26 | 1 | AISGSSLAHPQGKIS | Transmembrane |

| 30 | 1 | WLAMVLGLVAGLISV | Transmembrane |

| 31 | 1, 3, 7 | GLISVGGAKYLPGCC | Transmembrane |

| 32 | 1 | LPGCCNRVLGIPHSS | Intracellular |

| 33 | 1 | IPHSSIMGYNFSLLG | Intracellular |

| 34 | 1 | FSLLGLLDEIIYIVL | Transmembrane |

| 35 | 1 | IYIVLLVLDTVGAGN | Transmembrane |

| 40 | 1 | IWKAPHEAKYFDDQV | Intracellular |

| Cc/Ee-specific | |||

| 6 | 2 | QDLTVMAALGLGFLT | Transmembrane |

| 10 | 2 | ILLDGFLSQFPPGKV | Extracellular |

| 12 | 3 | SIRLATMSAMSVLIS | Transmembrane |

| 13 | 4, 5 | SVLISAGAVLGKVNL | Transmembrane |

| 19 | 2 | TVAWCLPKPLPKGTE | Intracellular |

| 23 | 2 | SVNSPLLRSPIQRKN | Extracellular |

| 26 | 2 | AISGSSLAHPQRKIS | Transmembrane |

| 30 | 7 | WLAMVLGLVAGLISI | Transmembrane |

| 32 | 7 | LPVCCNRVLGIHHIS | Intracellular |

| 36 | 1 | VWNGNGMIGFQVLLS | Extracellular |

| Cc/Ee and D shared | |||

| 1 | 3, 6 | SSKYPRSVRRCLPLW | Intracellular |

| 2 | 4, 5 | CLPLWALTLEAALIL | Transmembrane |

| 3 | 1, 6 | AALILLFYFFTHYDA | Transmembrane |

| 4 | 1, 6 | THYDASLEDQKGLVA | Extracellular |

| 5 | 6 | KGLVASYQVGQDLTV | Extracellular |

| 8 | 1, 6 | HSWSSVAFNLFMLAL | Intracellular |

| 9 | 1 | FMLALGVQWAILLDG | Transmembrane |

| 14 | 6 | GKVNLAQLVVMVLVE | Intracellular |

| 21 | 6 | ATIPSLSAMLGALFL | Transmembrane |

| 28 | 7 | SAVLAGGVAVGTSCH | Transmembrane |

| 29 | 3, 6 | GTSCHLIPSPWLAMV | Extracellular |

| 37 | 1 | QVLLSIGELSLAIVI | Extracellular |

| 38 | 6 | LAIVIALTSGLLTGL | Transmembrane |

| 39 | 1 | LLTGLLLNLKIWKAP | Intracellular |

| Stimulatory Peptide . | Responding Case Nos. . | Sequence . | Predicted Topography3-150 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-specific | |||

| 6 | 1 | QDLTVMAAIGLGFLT | Transmembrane |

| 7 | 1 | LGFLTSSFRRHSWSS | Transmembrane |

| 10 | 1 | ILLDGFLSQFPSGKV | Extracellular |

| 11 | 1 | PSGKVVITLFSIRLA | Extracellular |

| 12 | 1 | SIRLATMSALSVLIS | Transmembrane |

| 13 | 1 | SVLISSVDAVLGKVNL | Transmembrane |

| 15 | 1 | MVLVEVTALGNLRMV | Transmembrane |

| 16 | 1 | NLRMVISNIFNTDYH | Extracellular |

| 19 | 3, 7 | SVAWCLPKPLPEGTE | Intracellular |

| 22 | 1, 7 | GALFLWIFWPSFNSA | Transmembrane |

| 23 | 1 | SFNSALLRSPIERKN | Extracellular |

| 24 | 1 | IERKNAVFNTYYAVA | Transmembrane |

| 25 | 1, 3 | YYAVAVSVVTAISGS | Transmembrane |

| 26 | 1 | AISGSSLAHPQGKIS | Transmembrane |

| 30 | 1 | WLAMVLGLVAGLISV | Transmembrane |

| 31 | 1, 3, 7 | GLISVGGAKYLPGCC | Transmembrane |

| 32 | 1 | LPGCCNRVLGIPHSS | Intracellular |

| 33 | 1 | IPHSSIMGYNFSLLG | Intracellular |

| 34 | 1 | FSLLGLLDEIIYIVL | Transmembrane |

| 35 | 1 | IYIVLLVLDTVGAGN | Transmembrane |

| 40 | 1 | IWKAPHEAKYFDDQV | Intracellular |

| Cc/Ee-specific | |||

| 6 | 2 | QDLTVMAALGLGFLT | Transmembrane |

| 10 | 2 | ILLDGFLSQFPPGKV | Extracellular |

| 12 | 3 | SIRLATMSAMSVLIS | Transmembrane |

| 13 | 4, 5 | SVLISAGAVLGKVNL | Transmembrane |

| 19 | 2 | TVAWCLPKPLPKGTE | Intracellular |

| 23 | 2 | SVNSPLLRSPIQRKN | Extracellular |

| 26 | 2 | AISGSSLAHPQRKIS | Transmembrane |

| 30 | 7 | WLAMVLGLVAGLISI | Transmembrane |

| 32 | 7 | LPVCCNRVLGIHHIS | Intracellular |

| 36 | 1 | VWNGNGMIGFQVLLS | Extracellular |

| Cc/Ee and D shared | |||

| 1 | 3, 6 | SSKYPRSVRRCLPLW | Intracellular |

| 2 | 4, 5 | CLPLWALTLEAALIL | Transmembrane |

| 3 | 1, 6 | AALILLFYFFTHYDA | Transmembrane |

| 4 | 1, 6 | THYDASLEDQKGLVA | Extracellular |

| 5 | 6 | KGLVASYQVGQDLTV | Extracellular |

| 8 | 1, 6 | HSWSSVAFNLFMLAL | Intracellular |

| 9 | 1 | FMLALGVQWAILLDG | Transmembrane |

| 14 | 6 | GKVNLAQLVVMVLVE | Intracellular |

| 21 | 6 | ATIPSLSAMLGALFL | Transmembrane |

| 28 | 7 | SAVLAGGVAVGTSCH | Transmembrane |

| 29 | 3, 6 | GTSCHLIPSPWLAMV | Extracellular |

| 37 | 1 | QVLLSIGELSLAIVI | Extracellular |

| 38 | 6 | LAIVIALTSGLLTGL | Transmembrane |

| 39 | 1 | LLTGLLLNLKIWKAP | Intracellular |

Location of most residues in peptide after Avent et al.14

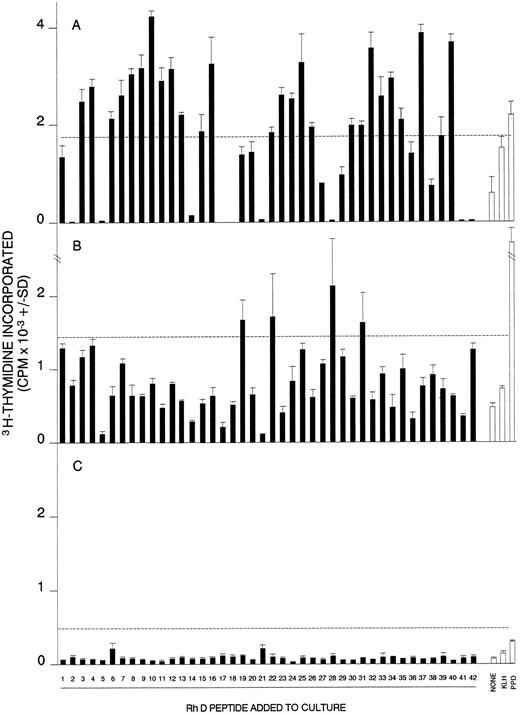

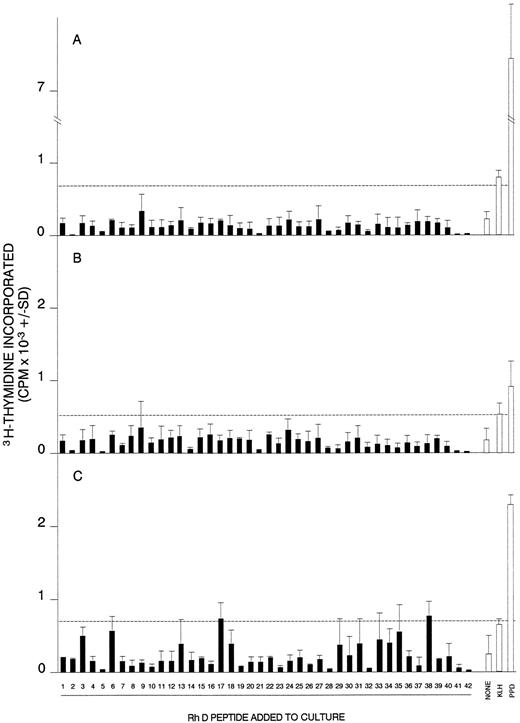

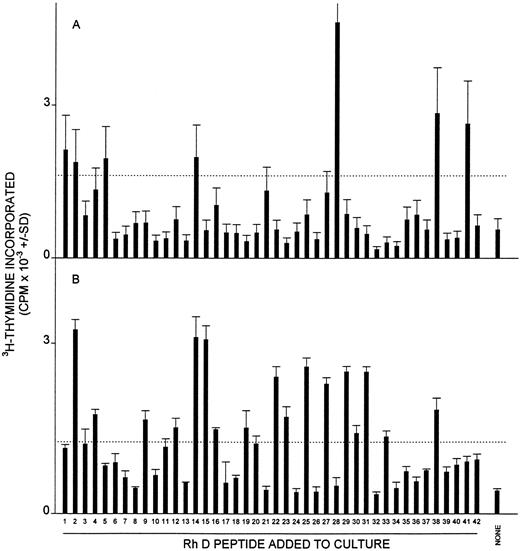

Proliferative responses of MCs obtained from AIHA cases no. 1 (A), 7 (B), and 8 (C) against the panel of 42 peptides corresponding to the Rh D protein. In each case, all the peptides were tested on a single occasion, and the dashed line indicates the level of proliferation taken as representing a positive response (the higher of SI = 3 or CPM = 500). Positive control responses to the foreign recall antigen PPD are also shown. The HLA-DR type of each patient was (1) DRB1*1501/2/3; DRB1*1303/4, (7) DRB1*4; DRB1*1401/4/5/7/8, and (8) DRB1*15; DRB1*0301.

Proliferative responses of MCs obtained from AIHA cases no. 1 (A), 7 (B), and 8 (C) against the panel of 42 peptides corresponding to the Rh D protein. In each case, all the peptides were tested on a single occasion, and the dashed line indicates the level of proliferation taken as representing a positive response (the higher of SI = 3 or CPM = 500). Positive control responses to the foreign recall antigen PPD are also shown. The HLA-DR type of each patient was (1) DRB1*1501/2/3; DRB1*1303/4, (7) DRB1*4; DRB1*1401/4/5/7/8, and (8) DRB1*15; DRB1*0301.

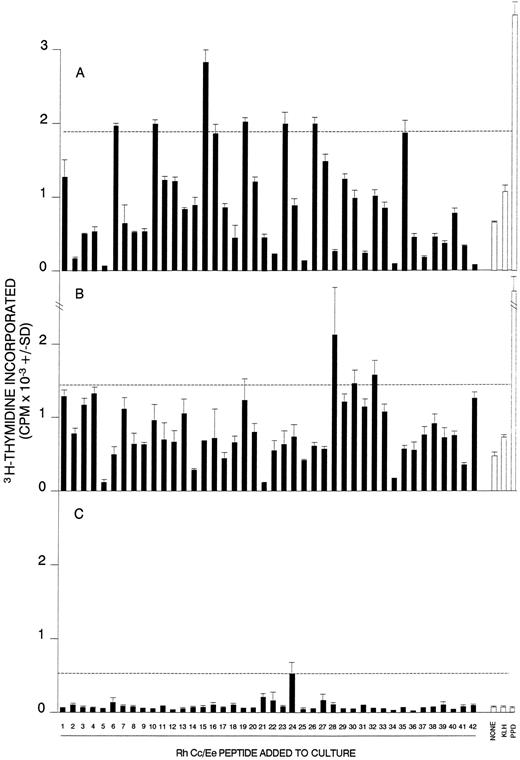

Proliferative responses of MCs obtained from AIHA cases no. 2 (A), 7 (B), and 8 (C) against the panel of 42 peptides corresponding to the Rh Cc/Ee protein. In each case, all the peptides were tested on a single occasion, and the dashed line indicates the level of proliferation taken as representing a positive response (the higher of SI = 3 or CPM = 500). Positive control responses to the foreign recall antigen PPD are also shown.

Proliferative responses of MCs obtained from AIHA cases no. 2 (A), 7 (B), and 8 (C) against the panel of 42 peptides corresponding to the Rh Cc/Ee protein. In each case, all the peptides were tested on a single occasion, and the dashed line indicates the level of proliferation taken as representing a positive response (the higher of SI = 3 or CPM = 500). Positive control responses to the foreign recall antigen PPD are also shown.

Determination of autoantibody specificity.Autoantibody eluted by ether treatment16 from the RBCs of AIHA patients, or serum antibody, was screened in hemagglutination assays for the ability to bind a panel of RBCs consisting of MKMK, U — , Rhnull , .D., LW(a — b — ), Oh, Fy(a — b — ). Lu(a — b — ). Ko, Rw1R1 , R2R2 , r′r, r′′r, and rr cells. Antibody that was considered to be Rh-specific failed to react with Rh null and .D. cells, but agglutinated RBCs of all other phenotypes tested. Autoantibody reactive with the entire panel of RBCs was classified as panagglutinin. Panagglutinin-containing eluates were absorbed with an equal volume of Rh null cells and retested against the panel of RBCs to determine whether Rh-specific antibodies were also present.

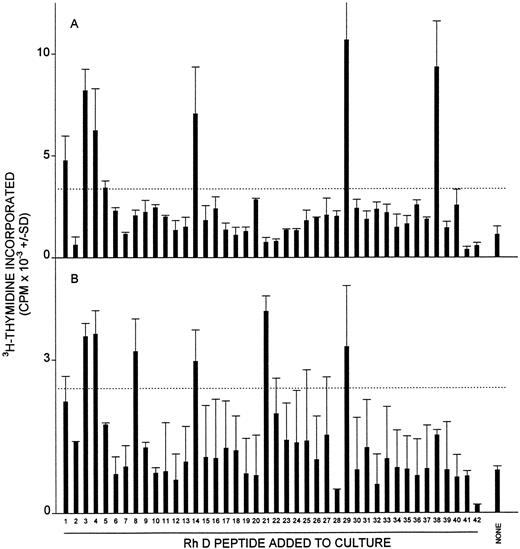

Proliferative responses of MCs from AIHA case no. 6 against the panel of 42 peptides corresponding to the Rh D protein on two occasions (A and B) 3 months apart. The hemoglobin level of the patient on each occasion was 10.0 and 10.1 g/dL, respectively, and the treatment was unchanged (10 mg prednisolone daily). The dashed line indicates the level of proliferation taken as representing a positive response (the higher of SI = 3 or CPM = 500).

Proliferative responses of MCs from AIHA case no. 6 against the panel of 42 peptides corresponding to the Rh D protein on two occasions (A and B) 3 months apart. The hemoglobin level of the patient on each occasion was 10.0 and 10.1 g/dL, respectively, and the treatment was unchanged (10 mg prednisolone daily). The dashed line indicates the level of proliferation taken as representing a positive response (the higher of SI = 3 or CPM = 500).

Antigens and mitogens.Two complete panels of 42 15-mer peptides, with 5 amino acid overlaps, were synthesized (Multiple Peptide Service, Cambridge Research Biochemicals, Cheshire, UK) corresponding to the sequences of the 30-kD Rh proteins associated with expression of the D or Cc/Ee blood group antigens, respectively (ie, D peptides 1-42 and Cc/Ee peptides 1-42). The amino acid sequences for each of these proteins have been deduced independently from cDNA analyses by two laboratories.12-15 Because the two polypeptide sequences show 92% homology, 16 of the synthetic peptides were shared between the panels (numbering from the amino terminus, peptides 1-5, 8, 9, 14, 21, 28, 29, 37-39, 41, and 42). To ensure purity, each panel was synthesized by fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl chemistry on resin using a base-labile linker, rather than by conventional pin technology, and randomly selected peptides were screened by high-performance liquid chromatography and amino acid analysis. The peptides were used to stimulate cultures at 20 μg/mL, although it should be noted that the responses of the cultures had previously been shown to be similar in magnitude and kinetics at peptide concentrations between 5 and 20 μg/mL.

The control antigens Mycobacterium tuberculosis-purified protein derivative (PPD; Statens Seruminstitut, Copenhagen, Denmark) and keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH; Calbiochem-Behring, La Jolla, CA) were dialyzed extensively against phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4 (PBS), and filter sterilized before addition to cultures at 50 μg/mL. PPD, but not KLH, readily provokes recall T-cell responses in vitro,17 because most UK citizens have been immunized with Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG). Concanavalin A (Con A) was obtained from Sigma (Poole, Dorset, UK) and used to stimulate cultures at 10 μg/mL.

Antibodies.Fluorescein isothiocyanate- or phycoerythrin-conjugated MoAbs against human CD3, CD19, CD45, or CD14 were obtained from Dako Ltd (High Wycombe, Bucks, UK). Blocking MoAbs specific for HLA-DP, -DQ, or -DR (Becton Dickinson, Oxford, UK) were dialyzed thoroughly against PBS before addition to cultures at the previously determined optimum concentration of 2.5 μg/mL.

Isolation of splenic mononuclear cells (SMCs) or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and T cells.SMCs were obtained from homogenized spleen tissue by centrifugation on Ficoll-Hypaque (Sigma) and stored frozen under liquid nitrogen until needed. PBMCs were separated from fresh blood samples using Ficoll-Hypaque. The viability of SMCs and PBMCs was greater than 90% in all experiments, as judged by trypan blue exclusion. T cells were isolated from SMCs or PBMCs by passage through glass bead affinity columns coated with human IgG/sheep antihuman IgG immune complexes.18 Flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson FACScan) showed that typical preparations contained more than 95% T cells.

Cell proliferation assays.SMCs or PBMCs were cultured in 100 μL volumes in microtiter plates at a concentration of 1.25 × 106 cells/mL in the Alpha Modification of Eagle's Medium (ICN Flow, Bucks, UK) supplemented with 5% autologous serum, 4 mmol/L L-glutamine (GIBCO, Paisley, UK), 100 U/mL sodium benzylpenicillin G (Sigma), 100 μg/mL streptomycin sulphate (Sigma), 5 × 10−5 mol/L 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), and 20 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.2 (Sigma). All plates were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 /95% air. The cell proliferation in cultures was estimated from the incorporation of 3H-thymidine in triplicate wells 5 days after stimulation with antigen, as described previously.19 Purified T cells were cultured under similar conditions at 1.25 × 106 cells/mL, together with unfractionated MCs that had been irradiated with 2,000 rad to prevent their proliferation and that were added to the wells at a final concentration of 0.6 × 106 cells/mL to act as antigen-presenting cells (APCs). In some experiments, these cultures were performed in 2-mL wells and the incorporation of 3H-thymidine was measured in triplicate 100-μL samples withdrawn from the plates over the period 4 to 9 days after stimulation. Proliferation results are presented either as the mean counts per minute (CPM) ± SD of the triplicate samples or as a stimulation index (SI) expressing the ratio of mean CPM in stimulated versus unstimulated control cultures. An SI > 3 with CPM > 500 is interpreted as representing a positive response.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for binding of RBC autoantibody to Rh peptides.Eluted autoantibody was screened for the ability to bind Rh peptides by modifying an ELISA previously used to measure reactivity with other RBC components.11 Briefly, 50-μL volumes of 20 μg/mL Rh peptide in carbonate buffer, pH 9.6, were coated overnight at 4°C onto duplicate wells of flat-bottomed microtiter plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). After washing, the wells were blocked with 100 μL PBS containing 1% wt/vol bovine serum albumin and incubated with 50 μL eluted antibody for 1 hour at 37°C. The plates were then successively washed and incubated with 50-μL volumes of rabbit antiserum to human IgG Fc (Nordic, Maidenhead, UK) and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibody specific for rabbit IgG (Sigma). Finally, wells were developed with 50 μL phophatase substrate (Sigma) and the absorbence measured at 405 nm using a Multiskan MS reader (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland). The results are expressed as the mean optical density of duplicate readings minus the background in uncoated wells (ΔOD).

RESULTS

Proliferative responses of SMCs or PBMCs from AIHA patients to Rh protein peptides.The two panels of synthetic peptides, corresponding to the sequences of the Rh D and Rh Cc/Ee proteins, were screened for the ability to stimulate the proliferation of MCs from each of the AIHA patients. Proliferation was assessed on day 5 after stimulation, and cell culture was performed in microtiter plates without enrichment of T cells, conditions that strongly favor recall, rather than primary, responses.17 20-22 The results are summarized in Table 2. In most patients it was not possible to test all the peptides on one occasion, and the results were obtained by compiling data from a number of experiments using repeat blood samples. The screening studies showed that two or more peptides elicited proliferative responses in cases no. 1 through 7, but that PBMCs from cases no. 8 and 9 failed to respond to any members of either panel on two occasions.

Is the distinction between responding and nonresponding patients specific to proliferation against the Rh peptides? If failure of MCs from cases no. 8 and 9 to respond to the peptides was due to a general immune dysfunction, then it would be expected that their MCs would also be unable to proliferate in response to other stimuli. MCs from cases no. 1 through 7 and 9 responded to both the T-cell mitogen Con A (SI > 5.4) and the recall foreign antigen PPD (SI > 3.6), but neither stimulus elicited a response in case no. 8 (SI < 2.2, CPM < 300). Note that failure to respond is not correlated with the administration of immunosuppressive or corticosteroid treatment (compare with Table 1).

Responsiveness of MCs to Stimulatory Rh Peptides on Different Occasions

| Case No. . | Peptide Tested . | PBMC Response to Peptide . | Hemoglobin (g/dL) . | Interval . | Change in Treatment . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Occasion 1 . | Occasion 2 . | Occasion 1 . | Occasion 2 . | . | . |

| 3 | D/Cc/Ee 1 | + | + | 11.2 | 12.0 | 1 yr | None |

| D 12 | + | − | |||||

| 4 | D/Cc/Ee 2 | + | + | 6.9 | 6.9 | 1 wk | Prednisolone started by occasion 2 |

| Cc/Ee 13 | + | − | |||||

| 5 | D/Cc/Ee 2 | + | + | 6.8 | 12.6 | 4 mo | None |

| Cc/Ee 13 | − | + | |||||

| Case No. . | Peptide Tested . | PBMC Response to Peptide . | Hemoglobin (g/dL) . | Interval . | Change in Treatment . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Occasion 1 . | Occasion 2 . | Occasion 1 . | Occasion 2 . | . | . |

| 3 | D/Cc/Ee 1 | + | + | 11.2 | 12.0 | 1 yr | None |

| D 12 | + | − | |||||

| 4 | D/Cc/Ee 2 | + | + | 6.9 | 6.9 | 1 wk | Prednisolone started by occasion 2 |

| Cc/Ee 13 | + | − | |||||

| 5 | D/Cc/Ee 2 | + | + | 6.8 | 12.6 | 4 mo | None |

| Cc/Ee 13 | − | + | |||||

Distribution of stimulatory Rh peptides in responding patients.Are stimulatory peptides restricted to particular regions of the Rh proteins? Table 2 shows that, in the responding patient group as a whole, peptides that elicited responses were identified throughout D- and Cc/Ee-specific sequences and in conserved regions. The sequences and predicted topography of these peptides are listed in Table 3, and it can be seen that stimulatory regions are derived not only from extracellular loops of the Rh proteins, but also from membrane spanning domains and intracellular loops.

Because the Rh D and Cc/Ee proteins show 92% homology, those peptides that correspond to nonconserved regions typically differ by only one to three amino acids. Despite this similarity, the question arises as to whether any of the unique peptides that are stimulatory also cross-react with their homologues from the alternative sequence. Analysis of the results shown in Tables 2 and 3 shows that, in every case in which nonconserved peptides elicited proliferation, the responses were provoked by only one of the D or Cc/Ee homologues.

Do the same Rh peptides stimulate proliferative responses of MCs from different patients? It can be seen from Table 2 that, in the seven AIHA cases with positive responses to the panels, there were six different profiles of stimulatory peptides. These patterns were identical only in cases no. 4 and 5, in which responses were elicited by peptide 13 from the Cc/Ee protein and by peptide 2 common to both Rh proteins. Most of the other stimulatory peptides each provoked responses in only a single case, with the exceptions of D-specific peptides 19, 22, 25, and 31 and peptides 1, 3, 4, 8, and 29 shared between the Cc/Ee and D proteins.

Entire peptide panels were screened simultaneously whenever sufficient MCs were obtained from individual donations by AIHA patients, and representative results are depicted in Figs 1 and 2. These experiments further illustrate that the profiles of the responses to the Rh peptides can vary markedly between different cases, and it is also evident that the stimulatory peptides tend to occur in clusters along the D and Cc/Ee proteins. Note also that the culture conditions support control recall responses to PPD, but not primary responses to KLH. Because major histocompatibility complex (MHC) type is one factor that may influence the distribution of peptides that elicit responses, the HLA-DR classification of patients was determined where possible. It can be seen from Fig 1 that the HLA-DR type does vary between cases with different response profiles. Unfortunately, patient mortality and limitations on blood sampling precluded the MHC typing of other cases, including cases no. 4 and 5, whose MCs, as already noted, responded to identical peptides.

To determine whether the patterns of Rh peptides that evoke responses change with time in each patient, the entire panel from the D protein was screened in case no. 6 on two occasions 3 months apart (Fig 3). It can be seen that peptides 3, 4, 14, and 29 were stimulatory on both dates, whereas responsiveness to peptides 1, 5, and 38 was lost and reactivity to peptides 8 and 21 was gained. Although the results show that stimulatory profiles do change with time, this variation is much less than that observed between different patients (compare Fig 3 with Figs 1 and 2). Retesting selected stimulatory peptides in cases no. 3, 4, and 5 further shows that the ability to respond to some peptides can be maintained over periods up to 1 year, but confirms that responsiveness to others may be lost or gained (summarized in Table 4). It should be noted that, in all cases, the evolution of the response is independent of changes in treatment or the severity of disease.

Proliferative responses of purified splenic T cells from AIHA case no. 1 against Rh peptides that had elicited proliferation of SMCs.

Proliferative responses of purified splenic T cells from AIHA case no. 1 against Rh peptides that had elicited proliferation of SMCs.

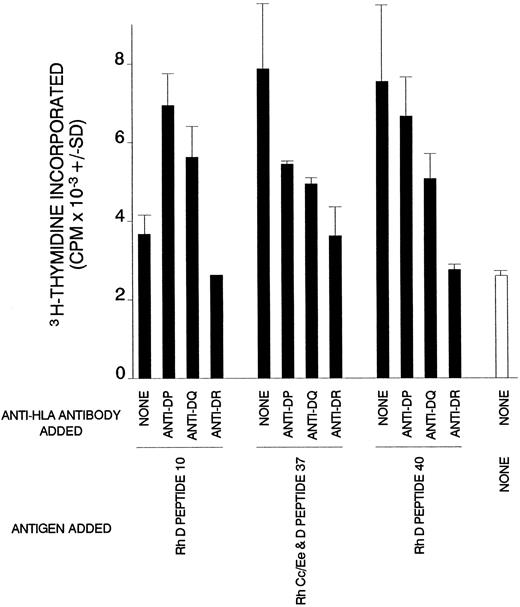

Dependency on HLA class II of T-cell proliferation against Rh peptides in AIHA case no. 1. Cultures of splenic T cells were stimulated with Rh peptides and class II-restricted responses were blocked by the addition of antibody specific for DP, DQ, or DR.

Dependency on HLA class II of T-cell proliferation against Rh peptides in AIHA case no. 1. Cultures of splenic T cells were stimulated with Rh peptides and class II-restricted responses were blocked by the addition of antibody specific for DP, DQ, or DR.

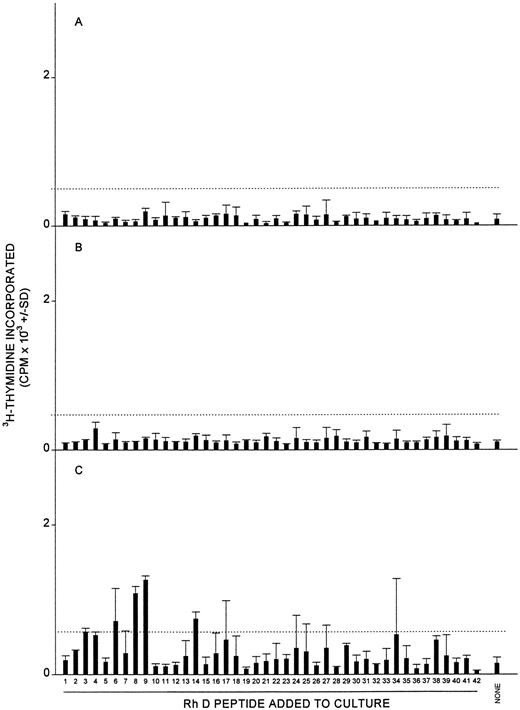

Proliferative responses of MCs obtained from three healthy donors (A, B, and C) against the panel of 42 peptides corresponding to the Rh D protein. In each case, all the peptides were tested on a single occasion, and the dashed line indicates the level of proliferation taken as representing a positive response (the higher of SI = 3 or CPM = 500). Positive control responses to the foreign recall antigen PPD are also shown.

Proliferative responses of MCs obtained from three healthy donors (A, B, and C) against the panel of 42 peptides corresponding to the Rh D protein. In each case, all the peptides were tested on a single occasion, and the dashed line indicates the level of proliferation taken as representing a positive response (the higher of SI = 3 or CPM = 500). Positive control responses to the foreign recall antigen PPD are also shown.

Details of AIHA-Negative Control Patients

| Patient No. . | Age (yr)/Sex . | Samples Obtained . | Hemoglobin . | Reticulocytes . | Diagnosis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | (g/dL) . | (%) . | . |

| C1 | 55/F | Peripheral blood | 11.4 | 2.9 | Cold hemagglutinin disease |

| C2 | 77/F | Peripheral blood | 9.9 | 6 | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| C3 | 67/F | Peripheral blood | 11.7 | 1.4 | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| C4 | 38/F | Peripheral blood | 10.7 | Not recorded | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| C5 | 70/F | Peripheral blood | 7.6 | 1.1 | Autoimmune thrombocytopenia |

| C6 | 65/F | Peripheral blood | 7.2 | 7.6 | Lymphoma |

| C7 | 76/M | Peripheral blood | 9.4 | Not recorded | Chronic renal failure |

| C8 | 32/F | Peripheral blood | 9.5 | Not recorded | Chronic renal failure |

| C9 | 60/F | Peripheral blood | 8.3 | Not recorded | Chronic renal failure |

| Patient No. . | Age (yr)/Sex . | Samples Obtained . | Hemoglobin . | Reticulocytes . | Diagnosis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | (g/dL) . | (%) . | . |

| C1 | 55/F | Peripheral blood | 11.4 | 2.9 | Cold hemagglutinin disease |

| C2 | 77/F | Peripheral blood | 9.9 | 6 | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| C3 | 67/F | Peripheral blood | 11.7 | 1.4 | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| C4 | 38/F | Peripheral blood | 10.7 | Not recorded | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| C5 | 70/F | Peripheral blood | 7.6 | 1.1 | Autoimmune thrombocytopenia |

| C6 | 65/F | Peripheral blood | 7.2 | 7.6 | Lymphoma |

| C7 | 76/M | Peripheral blood | 9.4 | Not recorded | Chronic renal failure |

| C8 | 32/F | Peripheral blood | 9.5 | Not recorded | Chronic renal failure |

| C9 | 60/F | Peripheral blood | 8.3 | Not recorded | Chronic renal failure |

Proliferative responses of MCs obtained from patient C1 with cold hemagglutinin disease (A), patient C4 with systemic lupus erythematosus (B), and patient C9 with chronic renal failure (C) against the panel of 42 peptides corresponding to the Rh D protein. In each case, all the peptides were tested on a single occasion, and the dashed line indicates the level of proliferation taken as representing a positive response (the higher of SI = 3 or CPM = 500).

Proliferative responses of MCs obtained from patient C1 with cold hemagglutinin disease (A), patient C4 with systemic lupus erythematosus (B), and patient C9 with chronic renal failure (C) against the panel of 42 peptides corresponding to the Rh D protein. In each case, all the peptides were tested on a single occasion, and the dashed line indicates the level of proliferation taken as representing a positive response (the higher of SI = 3 or CPM = 500).

Specificity of Autoantibody From AIHA Patients and Reactivity of T Cells With Rh Peptides In Vitro

| Case No. . | Autoantibody Specificity . | T-Cell Reactivity . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Rh-Specific . | Panagglutinin . | Not Determined6-150 . | With Rh Peptides . |

| 1 | + | − | − | + |

| 2 | + | + | − | + |

| 3 | − | + | − | + |

| 4 | + | − | − | + |

| 5 | + | − | − | + |

| 6 | − | − | + | + |

| 7 | − | − | + | + |

| 8 | − | + | − | − |

| 9 | − | − | + | − |

| Case No. . | Autoantibody Specificity . | T-Cell Reactivity . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Rh-Specific . | Panagglutinin . | Not Determined6-150 . | With Rh Peptides . |

| 1 | + | − | − | + |

| 2 | + | + | − | + |

| 3 | − | + | − | + |

| 4 | + | − | − | + |

| 5 | + | − | − | + |

| 6 | − | − | + | + |

| 7 | − | − | + | + |

| 8 | − | + | − | − |

| 9 | − | − | + | − |

Autoantibody of insufficient titer to determine specificity.

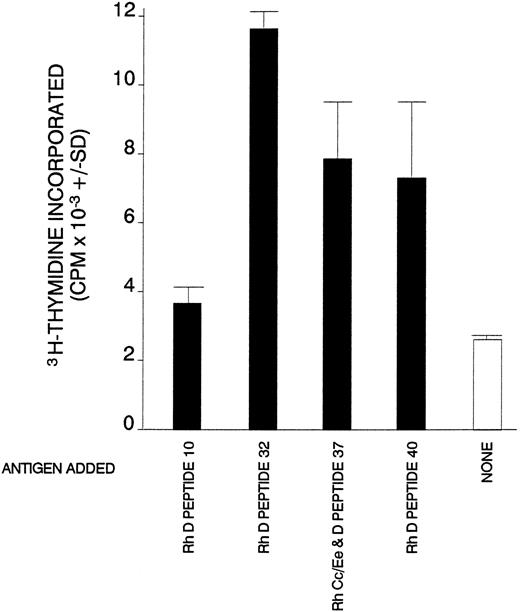

Characteristics of cellular proliferation against Rh protein peptides.Experiments were set up to determine whether the cells that proliferate in vitro in response to the Rh peptides were T lymphocytes that recognize the peptides in the context of MHC class II restriction elements. Affinity chromatography was used to purify T cells from SMCs in case no. 1, and these lymphocytes were tested for the ability to respond to four peptides that had elicited the proliferation of unfractionated cells. Figure 4 shows that generally, as expected, the purified T cells responded more strongly, although the proliferation against one peptide was weak. Similar results were obtained when T cells were obtained from the PBMCs of case no. 4 (results not shown). The ability of blocking antibodies specific for MHC class II molecules to inhibit the peptide-induced proliferation of purified T cells from case no. 1 was ascertained. It is evident from Fig 5 that the addition of anti-DR to cultures abrogated the responses to all the peptides tested. In contrast, the effects of anti-DP or -DQ antibodies were more varied, ranging from partial inhibition of proliferation to enhancement of the T-cell response against one of the peptides.

Relationship between T-cell responsiveness to Rh peptides and anti-RBC autoantibody production.If the T cells that respond to Rh peptides under culture conditions biased towards supporting only recall proliferation do provide help for pathogenic anti-RBC antibody generation in vivo, then four predictions can be made. The first prediction, that such responsiveness should be uncommon in healthy individuals, was tested by determining whether the SMCs or PBMCs from nine normal donors were able to proliferate under similar conditions against the Rh peptide panels. In seven cases, the panels were not stimulatory, but the PBMCs from two individuals proliferated against two or more peptides. Figure 6 depicts representative results from nonresponsive (Fig 6A and B) and responsive (Fig 6C) healthy donors. Because it could be argued that T-cell responsiveness to the Rh peptides in primary AIHA cases is a consequence, rather than a cause, of the disease, the panels were also tested for the ability to stimulate PBMCs from nine patients with other immunologic or nonimmunologic causes of anemia. The details of these control patients are summarized in Table 5. No PBMC responses were evoked by the peptides in eight of these cases, including one patient with cold hemagglutinin disease, three with systemic lupus erythematosus, one with autoimmune thrombocytopenia, one with lymphoma, and two with chronic renal failure (representative results from these patients are shown in Fig 7A and B). In only one control patient, who was suffering from chronic renal failure, three peptides provoked weak responses (Fig 7C).

Secondly, it can be predicted that, in the series of primary AIHA patients, there should be a relationship between the demonstration of T-cell responsiveness to the Rh peptides and the presence of antibodies reactive with the Rh proteins. The specificity of the autoantibodies from each of the cases was therefore determined and the results are summarized in Table 6. It can be seen that particular Rh peptides were indeed stimulatory in cases no. 1, 4, and 5, the three cases with Rh-reactive autoantibody, and in case no. 2, whose mixed antibodies included those with Rh specificity. Furthermore, no anti-Rh autoantibodies were detectable in either of the cases no. 8 or 9, in which PBMCs were consistently unresponsive to both panels. However, only panagglutinin antibodies were identified in case no. 3, and the autoantibody specificity could not be determined in cases no. 6 and 7, despite the demonstration of Rh-peptide reactive PBMCs.

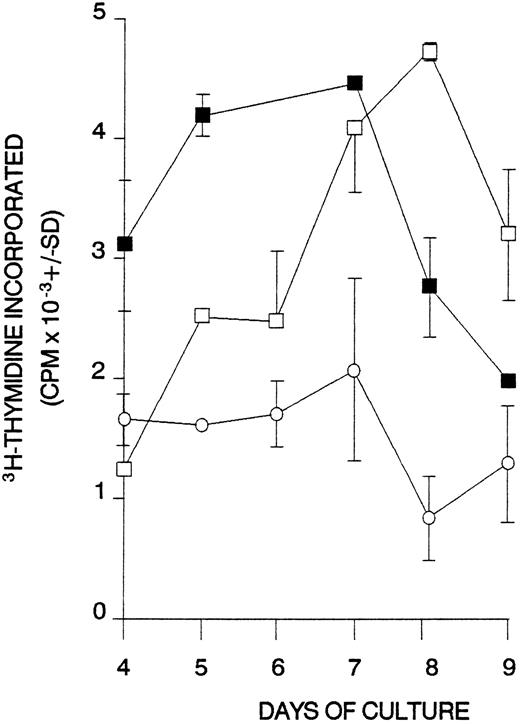

The third prediction is that, if T cells reactive with particular peptides from the Rh proteins are capable of driving autoantibody production, then they will also respond to the native proteins from the RBC membrane processed by APCs. Figure 8 shows that splenic T cells from case no. 1 proliferated not only to Rh peptides, but also to RBCs bearing the D and/or Cc/Ee Rh proteins. No such responses to RBCs were elicited (SI < 1.4) when SMCs or PBMCs were obtained from healthy donors (n = 10) or from cases no. 8 and 9, in which the Rh peptides also failed to stimulate proliferation. Rh null RBCs lacking the Rh D and Cc/Ee proteins were tested in control donors and AIHA patients, but, although as predicted there was no response, these fragile RBCs lyse in culture medium and nonspecifically inhibit T-cell proliferation to less than background levels (mean SI = 0.7).

Proliferative responses of splenic T cells obtained from AIHA case no. 1 against RBCs. Antigens were added to cultures as follows: (□) D-positive RBCs; (▪) D-negative RBCs; (○) unstimulated control.

Proliferative responses of splenic T cells obtained from AIHA case no. 1 against RBCs. Antigens were added to cultures as follows: (□) D-positive RBCs; (▪) D-negative RBCs; (○) unstimulated control.

Finally, T cells from D-negative healthy donors who have produced anti-D antibodies as a result of alloimmunization with the RhD blood group antigen should also proliferate in response to peptides from the D protein. Figure 9 shows that multiple peptides were stimulatory in two such donors.

T-cell proliferative responses against the panel of 42 Rh D peptides in two healthy D-negative donors (A and B) with alloantibodies specific for the Rh D blood group antigen. In each case, all the peptides were tested on a single occasion, and the dashed line indicates the level of proliferation taken as representing a positive response (the higher of SI = 3 or CPM = 500).

T-cell proliferative responses against the panel of 42 Rh D peptides in two healthy D-negative donors (A and B) with alloantibodies specific for the Rh D blood group antigen. In each case, all the peptides were tested on a single occasion, and the dashed line indicates the level of proliferation taken as representing a positive response (the higher of SI = 3 or CPM = 500).

If both helper T cells and autoantibody are specific for the Rh proteins in AIHA, the question arises as to whether they recognize the same epitopes. To address this question, autoantibody eluted from the RBCs of AIHA cases no. 1 and 5 was tested for the ability to bind the Rh peptides that elicited proliferation of their MC. Autoantibody from neither patient reacted with any of the corresponding stimulatory peptides listed in Table 2 (ΔOD < 0.05). In addition, no reactivity was detected with any nonstimulatory peptides, with the exception of weak binding of autoantibody from case no. 1 to peptide D/Cc/Ee 1 (ΔOD = 0.170).

DISCUSSION

The main finding reported here is that activated T cells capable of mounting recall responses to epitopes on the Rh proteins are present in the majority of human patients with AIHA, including all cases with autoantibodies that recognize the Rh complex. We5 and others7 have previously shown that the Rh proteins on the RBC membrane are important targets for pathogenic autoantibodies in humans, but the current work provides the first evidence that helper T cells do react with epitopes on these autoantigens and may therefore be responsible for driving the disease process.

It was shown by depletion experiments that the cells responding in vitro to the Rh peptides were T cells, and the ability of anti-DR antibodies to block consistently the proliferation indicated that these lymphocytes were predominantly MHC class II-restricted cells. Although DR appears to be the principal restricting class II locus, the effects of the blocking antibodies suggest that DP and DQ molecules may also compete for binding/presentation of particular Rh peptides. The specific nature of the in vitro T-cell responses to Rh peptides in human AIHA is shown by two findings. First, the profiles of stimulatory peptides were similar in only two cases. Secondly, nonconserved, but related, sequences from each of the two Rh proteins tested did not cross-react. The differences in profile of the peptide responses between patients may be related to the variations in the DR type of the cases and reflect both the ability of particular HLA molecules to bind and present each peptide and the role of the MHC in shaping the T-cell repertoire.23 The more limited changes in the patterns of stimulatory peptides with time demonstrate that the precise specificity of the autoimmune T-cell response evolves even when the disease appears clinically stable. Gain or loss of the ability to respond to some epitopes may result from the respective effects of epitope spreading24 and clonal exhaustion. Similar diversity and plasticity of self-recognition has recently been reported for T cells reactive with myelin proteolipid protein in multiple sclerosis.25

Is there any pattern to the distribution of autoreactive helper T-cell epitopes in the Rh proteins in AIHA? Alignment of the peptides that elicited responses with the sequences and predicted topography of the Rh D12,13 and Cc/Ee14,15 proteins shows that stimulatory epitopes are found throughout each of the molecules, in both extracellular or intracellular and membrane-spanning domains. The finding that Rh-reactive autoantibody failed to react well with any of the peptides indicates that the autoreactive T and B cells do not share the same epitopes and supports the view that autoantibody recognition is dependent on the conformation of the Rh proteins.5 This contrast in the distribution and form of the epitopes is not unexpected given the requirement for processing of antigen within APC before recognition by T cells26 and the likelihood that determinants bound by the pathogenic autoantibodies will be exposed on the outer surface of RBCs. Comparison of our results with the recently described blood group polymorphisms in the Rh proteins27 28 confirms that stimulatory Rh peptides in each responding patient did correspond to self, not foreign sequences, with the exception of Cc/Ee specific peptide 23 in case no. 2.

The key question that arises from the present work is whether the Rh-specific T cells that are activated in AIHA patients are indeed causally related to the disease in vivo. Evidence supporting a relationship includes the demonstration of Rh-reactive T cells in all AIHA patients with anti-Rh autoantibodies, the inability to identify such antibody in cases in which T cells consistently failed to respond to the Rh peptide panels, and the lack of responsiveness to the panels in most patients with other causes of anemia. Moreover, the paradigm emerging from studies of animal models of AIHA is that the target antigens bear pathogenic helper T-cell epitopes in addition to B-cell determinants.8-11,29,30 Although T cells were also responsive to the Rh peptides in three cases with no detectable Rh-specific antibody, in two cases the autoantibody was too weak to be defined and in the other it is possible that anti-Rh activity was masked serologically due to the presence of a strong panagglutinin. Alternatively, T cells specific for the Rh proteins may provide help for the panagglutinating antibodies against other molecules from the membrane, particularly nonprotein structures such as RBC phospholipid autoantigens31 that lack conventional T-cell epitopes.

The combined results of the current study and our previous work20 show that T cells capable of recall responses in vitro to the Rh peptides were not detected in 16 of 19 of healthy donors, providing further support for the view that such cells provide help for the production of anti-RBC autoantibodies. These findings do not conflict with the demonstration that the normal repertoire contains previously unstimulated immunologically ignorant T cells capable of giving responses in vitro to multiple epitopes on the Rh proteins.20 Such primary responses can only be detected using bulk cultures of highly enriched T cells17,20,21 after a relatively long incubation period.17 20-22 In contrast, cultures in the present work were performed using unfractionated cells in microtiter plates over a short time course, conditions designed to favor recall proliferation by primed T cells. Indeed, the results do validate the experimental design, because the conditions consistently support recall responses to PPD, but not proliferation to the nonrecall antigen KLH. Work to be published elsewhere (R.N.B. and C.J.E., manuscript in preparation) confirms that the culture period is critical in differentiating primary from recall responses in the case of Rh peptides: the proliferation of purified T cells from D-alloimmunized individuals to particular Rh D-specific peptides peaks on day 5 to 6 of bulk culture, whereas the maximal response of immunologically ignorant T cells from the same donors responding in vitro to autologous sequences occurs on day 8 to 9.

Given that Rh-specific helper T cells may drive the production of pathogenic autoantibodies in the majority of patients with AIHA, further important questions arise. First, how do these autoreactive T cells escape the mechanisms of clonal deletion32,33 and anergy34,35 that purge potentially autoaggressive cells from the repertoire during the induction of self-tolerance? Secondly, what causes these cells to be stimulated in AIHA? Thirdly, if such activated cells are pathogenic, why are they also present, albeit uncommonly, in some healthy individuals in the absence of harmful Rh-specific autoantibody production? These questions were addressed by a hypothesis that we have recently put forward for the induction of AIHA and other autoimmune diseases.36 As discussed above, we have previously shown that autoreactive T cells responsive to multiple epitopes on the Rh proteins do exist in all healthy humans, but that, as confirmed by the present study, these lymphocytes are not commonly activated in vivo.20 T cells of this type that evade repertoire purging and remain quiescent in the periphery, despite the presence of the autoantigen they recognize, may be termed immunologically ignorant.37,38 We predict that the Rh-reactive ignorant T cells are specific for epitopes that are not normally presented by APCs and that are therefore defined as cryptic,24,39 either because the corresponding peptides are not generated by processing of the antigen or because they bind with low affinity to their restricting MHC class II molecules.40 Our hypothesis proposes that ignorant T cells are activated in AIHA due to the coincidence of two independent events, namely persistent stimulation by cross-reactive environmental antigen(s) and Th1-lymphokine–induced changes in autoantigen processing that trigger the presentation of many previously cryptic epitopes. Thus, it is possible for healthy individuals to harbor activated Rh-specific T cells after encountering environmental antigen(s) that cross-reacts with the Rh proteins, but in the absence of a coincidental change in autoantigen processing, the corresponding Rh epitopes remain cryptic and no disease will result. The current findings, that T cells from AIHA patients but not healthy individuals can respond to native RBC proteins processed by APCs, are consistent with this interpretation.

One possibility that was not investigated in the current study is whether the Rh polypeptides are the only targets for activated autoreactive T cells in human AIHA. The notion that, in those patients with Rh-specific T cells, there may also be T cells that recognize other proteins is supported by our recent findings in other species: in NZB mouse AIHA and in a dog with the disease, T cells responded to multiple RBC membrane fractions.11 30 Another possibility, in a minority of human patients, is that neither autoantibodies nor T cells are specific for the Rh complex, but that both react with other RBC proteins. Such patients may include the two cases, one with panagglutinin and the other with antibody of undetermined specificity, whose T cells did not mount recall responses to the Rh peptide panels.

There is a pressing need to develop specific forms of therapy for autoimmune disease that are more potent than currently available treatments, but with less side-effects. As already mentioned, one approach that has proved successful in rodent models is peptide immunotherapy.1-3 The identification of helper T-cell epitopes on the Rh proteins is the first step towards the evaluation of such therapy in human AIHA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr J.L. Bidwell for assistance with HLA typing. We are also grateful to Dr M. Vickers and Prof M. Greaves for help in collecting blood samples from patients.

Supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust (UK) and ACTR Medical Research (Scotland).

Address reprint requests to Robert N. Barker, PhD, Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, University of Aberdeen, Foresterhill, Aberdeen AB25 2ZD, UK.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal