Abstract

Fas, a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF ) receptor superfamily is a critical downregulator of cellular immune responses. Proinflammatory cytokines like interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and TNF-α can induce Fas expression and render hematopoietic progenitor cells susceptible to Fas-induced growth suppression and apoptosis. Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1 ) is an essential anti-inflammatory cytokine, thought to play a key role in regulating hematopoiesis. In the present studies we investigated whether TGF-β1 might regulate growth suppression and apoptosis of murine hematopoietic progenitor cells signaled through Fas. In the presence of TNF, activation of Fas almost completely blocked clonogenic growth of lineage-depleted (Lin−) bone marrow (BM) progenitor cells in response to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF ), CSF-1, or a combination of multiple cytokines. Whereas TGF-β1 alone had no effect or stimulated growth in response to these cytokines, it abrogated Fas-induced growth suppression. Single-cell studies and delayed addition of TGF-β1 showed that the ability of TGF-β1 to inhibit Fas-induced growth suppression was directly mediated on the progenitor cells and not indirect through potentially contaminating accessory cells. Furthermore, TGF-β1 blocked Fas-induced apoptosis of Lin− BM cells, but did not affect Fas-induced apoptosis of thymocytes. TGF-β1 also downregulated the expression of Fas on Lin− BM cells. Thus, TGF-β1 potently and directly inhibits activation-dependent and Fas-mediated growth suppression and apoptosis of murine BM progenitor cells, an effect that appears to be distinct from its ability to induce progenitor cell-cycle arrest. Consequently, TGF-β1 might act to protect hematopoietic progenitor cells from enhanced Fas expression and function associated with proinflammatory responses.

HEMATOPOIESIS requires the continuous and balanced production of mature blood cells with a limited life span from a pool of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells.1,2 Many cytokines have been shown not only to stimulate the growth and differentiation of hematopoietic progenitor cells, but also to have a specific viability-promoting effect, in that they can counteract apoptosis.3 Other cytokines, including transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) mediate predominantly growth-suppressing effects and are capable of promoting apoptosis of hematopoietic progenitor cells.3-5 Although the mechanisms underlying their ability to induce apoptosis of progenitors are unclear, it seems that it at least in part involves their ability to inhibit the effects of viability-promoting cytokines.3,5,6 Signaling through Fas, a member of the TNF receptor superfamily, can potently induce apoptosis of multiple normal and transformed cell types.7-11 Fas and its ligand (FasL) play an important role in the development and selection of T and B cells,11,12 and are accordingly critically involved in downregulating the immune system. Loss-of-function mutations in Fas or FasL result in accumulation of activated lymphocytes, and development of autoimmune disease.12-15 Also, abnormally high activation of the Fas system may result in pathology, and Fas-mediated apoptosis has been implicated to be involved in the pathogenesis of diseases like acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and hepatitis.16-18

Because homeostatic regulation of hematopoiesis not only involves regulation of progenitor cell growth and differentiation, but probably also apoptosis,3 it is possible that Fas might be actively involved in regulation of normal hematopoiesis. This is supported by the expression of Fas on hematopoietic cell lines, as well as on mature lymphocytes, granulocytes, and macrophages which share a common stem cell.7,19,20 In addition, Fas activation might be involved in the pathophysiology of bone marrow (BM) failure syndromes.21

Recent studies showed that although human CD34+ BM cells do not constitutively express Fas, the proinflammatory cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α can induce Fas expression and responsiveness.22,23 Accordingly, Fas-induced apoptosis of hematopoietic progenitor cells might be involved in pathological BM suppression,21 and might also play a physiological role in limiting the progenitor cell response in situations of temporary demand for increased cell production. Because it is clear that the limited pool of primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells can be induced to express Fas, it is important to address whether any naturally occurring regulators might act to protect the progenitor cells from Fas-induced apoptosis.

TGF-β1 has been shown to predominantly inhibit the growth of hematopoietic progenitor cells in vitro, although it under certain conditions rather enhances progenitor cell growth.24,25 Particularly noteworthy are studies suggesting that hematopoietic progenitor cells might themselves produce TGF-β1 ,26,27 suggesting that it might be critically involved in maintaining the pool of hematopoietic progenitor cells. TGF-β1 is an essential anti-inflammatory cytokine, in that TGF-β1–deficient mice develop excessive inflammatory responses and early death,28,29 and in vitro TGF-β1 has been shown to potently inhibit a wide variety of proinflammatory cytokine responses.30 31 In the present study we investigated whether TGF-β1 might also interact with Fas-induced growth suppression and apoptosis of murine BM progenitor cells.

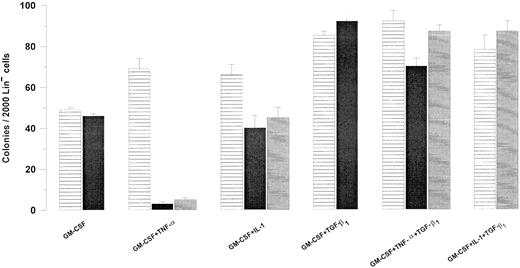

Effect of TGF-β1 on the Fas-responsiveness of Lin− BM progenitor cells. Two thousand Lin− murine BM cells were plated in IMDM containing 20% FCS, 1.2% methylcellulose, and cytokines at predetermined optimal concentrations as indicated. Cultures were incubated in the absence (▤) or presence of 0.5 μg/mL Jo2 added at initiation of culture (▪) or after 48 hours (▤). Colonies (<50 cells) were scored after 7 to 9 days of incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2 in air. An irrelevant hamster IgG control antibody had no effect on colony formation (data not shown). Results represent the mean values of three independent experiments with duplicate determinations; error bars show the SEM.

Effect of TGF-β1 on the Fas-responsiveness of Lin− BM progenitor cells. Two thousand Lin− murine BM cells were plated in IMDM containing 20% FCS, 1.2% methylcellulose, and cytokines at predetermined optimal concentrations as indicated. Cultures were incubated in the absence (▤) or presence of 0.5 μg/mL Jo2 added at initiation of culture (▪) or after 48 hours (▤). Colonies (<50 cells) were scored after 7 to 9 days of incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2 in air. An irrelevant hamster IgG control antibody had no effect on colony formation (data not shown). Results represent the mean values of three independent experiments with duplicate determinations; error bars show the SEM.

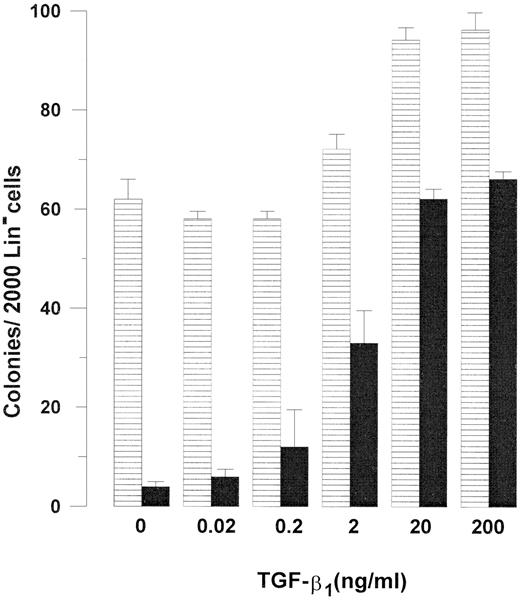

Concentration dependency of TGF-β1–mediated inhibition of Fas-induced growth suppression of Lin− BM cells. Two thousand Lin− BM cells were plated in IMDM supplemented with 20% FCS and 1.2% methylcellulose as described in Materials and Methods. All cultures were supplemented with GM-CSF 20 ng/mL and TNF-α 20 ng/mL, in the absence (▤) or presence (▪) of 0.5 μg/mL Jo2, from initiation of culture. As indicated, TGF-β1 was added at increasing concentrations. Cultures were scored for colony formation (<50 cells) after 7 to 9 days of incubation. An irrelevant hamster control IgG antibody had no effect on colony formation. Results represent the mean values from four separate experiments with duplicate determinations; error bars show the SEM.

Concentration dependency of TGF-β1–mediated inhibition of Fas-induced growth suppression of Lin− BM cells. Two thousand Lin− BM cells were plated in IMDM supplemented with 20% FCS and 1.2% methylcellulose as described in Materials and Methods. All cultures were supplemented with GM-CSF 20 ng/mL and TNF-α 20 ng/mL, in the absence (▤) or presence (▪) of 0.5 μg/mL Jo2, from initiation of culture. As indicated, TGF-β1 was added at increasing concentrations. Cultures were scored for colony formation (<50 cells) after 7 to 9 days of incubation. An irrelevant hamster control IgG antibody had no effect on colony formation. Results represent the mean values from four separate experiments with duplicate determinations; error bars show the SEM.

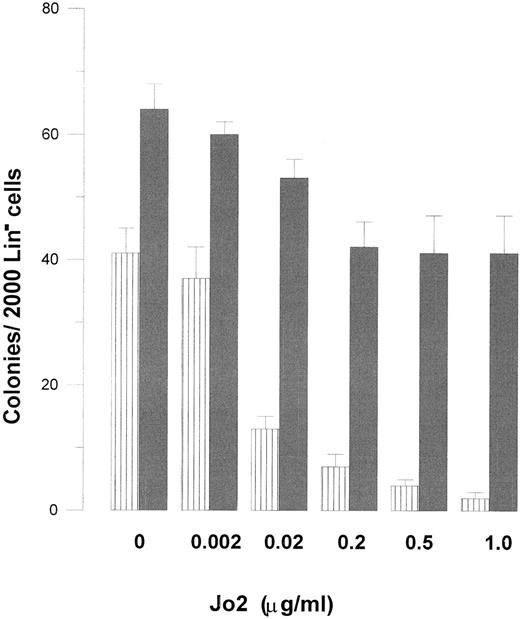

Concentration dependency of Jo2-induced growth suppression of Lin− BM progenitor cells in the absence and presence of TGF-β1 . Two thousand Lin− cells were plated in IMDM-based 1.2% methylcellulose (final concentration), and supplemented with 20% FCS, GM-CSF (20 ng/mL), and TNF-α (20 ng/mL). As indicated, cultures were incubated in the absence (▥) or presence () of TGF-β1 (20 ng/mL) and increasing concentrations of Jo2. After 7 to 9 days of incubation cultures were scored for colony formation (<50 cells). Irrelevant hamster control IgG antibody at concentrations up to 1 μg/mL had no effect on colony formation (data not shown). Results represent the mean values from four separate experiments with duplicate determinations; error bars show SEM.

Concentration dependency of Jo2-induced growth suppression of Lin− BM progenitor cells in the absence and presence of TGF-β1 . Two thousand Lin− cells were plated in IMDM-based 1.2% methylcellulose (final concentration), and supplemented with 20% FCS, GM-CSF (20 ng/mL), and TNF-α (20 ng/mL). As indicated, cultures were incubated in the absence (▥) or presence () of TGF-β1 (20 ng/mL) and increasing concentrations of Jo2. After 7 to 9 days of incubation cultures were scored for colony formation (<50 cells). Irrelevant hamster control IgG antibody at concentrations up to 1 μg/mL had no effect on colony formation (data not shown). Results represent the mean values from four separate experiments with duplicate determinations; error bars show SEM.

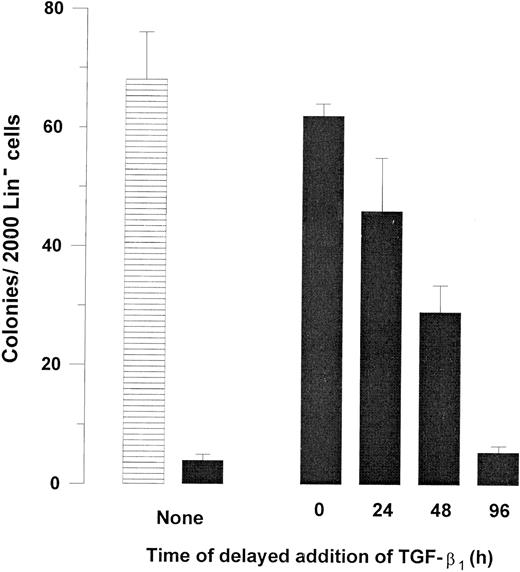

Kinetics of TGF-β1–induced inhibition of Fas response. Two thousand Lin− BM cells were plated in IMDM containing 20% FCS, 1.2% methylcellulose supplemented with 20 ng/mL GM-CSF, and 20 ng/mL TNF-α in the absence (▤) or presence (▪) of 0.5 μg/mL Jo2. TGF-β1 (20 ng/mL) was added as indicated at initiation of culture (0 hour) or after 24, 48, or 96 hours of incubation. Colonies were scored after a total of 7 to 9 days of incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2 in air. An irrelevant hamster IgG had no effect on colony formation. Results represent the mean values of three separate experiments with duplicate determinations; error bars show the SEM.

Kinetics of TGF-β1–induced inhibition of Fas response. Two thousand Lin− BM cells were plated in IMDM containing 20% FCS, 1.2% methylcellulose supplemented with 20 ng/mL GM-CSF, and 20 ng/mL TNF-α in the absence (▤) or presence (▪) of 0.5 μg/mL Jo2. TGF-β1 (20 ng/mL) was added as indicated at initiation of culture (0 hour) or after 24, 48, or 96 hours of incubation. Colonies were scored after a total of 7 to 9 days of incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2 in air. An irrelevant hamster IgG had no effect on colony formation. Results represent the mean values of three separate experiments with duplicate determinations; error bars show the SEM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cytokines and antibodies. Purified recombinant rat (rr) stem cell factor (SCF ), recombinant human (rHu) granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF ), and recombinant murine (rMu) granulocyte-macrophage CSF (GM-CSF ) were generously supplied by Amgen Corp (Thousand Oaks, CA). Purified rMu interleukin-1β (rMuIL-1β) and rMuIL-3 were from PeproTech Inc (Rocky Hill, NJ) and Promega Corp (Madison, WI), respectively. rHuIL-6 was a gift from Genetics Institute (Cambridge, MA). Purified rHu CSF-1 was kindly provided by Cetus (Emeryville, CA). rMuTNF-α was supplied by Genentech (San Francisco, CA) and rHuTGF-β1 was a gift from Tony Purchio (Oncogene Corp, Seattle, WA). A monoclonal hamster IgG anti-mouse Fas antibody (Jo2) was developed and purified as previously described,17 whereas fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated Jo2 as well as purified and FITC-conjugated irrelevant monoclonal hamster IgG control antibodies were from PharMingen (San Diego, CA). Unless otherwise indicated, all cytokines were used at predetermined optimal concentrations: rrSCF, 50 ng/mL; rHuG-CSF, 50 ng/mL; rMuGM-CSF, 20 ng/mL; rMuIL-1β, 20 ng/mL; rMuIL-3, 20 ng/mL; rHuIL-6, 50 ng/mL; rHuCSF-1, 50 ng/mL; rMuTNF-α, 20 ng/mL; and rHuTGF-β1 , 10 to 20 ng/mL. Purified Jo2 and an irrelevant control antibody were used at 0.5 to 2 μg/mL (based on titration on murine thymocytes, as previously described,32 as well as on Lin− cells in the present studies).

Isolation and enrichment of murine BM progenitors and thymocytes. Lin− BM cells were isolated from femurs and tibias of normal C57BL/6 mice (5 to 8 weeks old), as previously described.33-35 Briefly, unfractionated BM cells were incubated at 4°C for 30 minutes in a cocktail of lineage-specific antibodies (at predetermined optimal concentrations): RB6-8C5 (Gr-1), Lyt-2 (CD8a), L3T4 (CD4), LY-1 (CD5), MAC-1, and RA3-6B2 (B220) all from PharMingen, and Ter-119, generously supplied by Dr Tatsuo Kina (Chest Disease Research Institute, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan) in Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (IMDM; GIBCO, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 U/mL streptomycin and 20% fetal calf serum (FCS; Bio Whittaker, Walkersville, MD; complete IMDM). Sheep anti-rat IgG (Fc)-conjugated immunomagnetic beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) were added at a cell-to-bead ratio of 1:1 to 1:2 and incubated at 4°C for 45 minutes. Labeled (Lin+) cells were removed by a magnetic particle concentrator (Dynal), and lineage-depleted (Lin−) cells recovered from the supernatant. A second bead separation was performed with the same (absolute) number of beads. Thymocytes were isolated from the thymus of 5- to 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice.

Semisolid colony assay. Lin− BM cells were plated in 1 mL IMDM supplemented with 20% FCS, 1.2% (final concentrations) methylcellulose (Methocel; Fluka Chemie, Buchs, Switzerland), and cytokines at predetermined optimal concentrations in 35-mm Petri dishes. Cultures were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 in air for 7 to 9 (Lin− cells) or 12 days (Lin−Sca-1+ cells), at which time colonies (>50 cells) were scored according to established criteria.36

Single-cell assay. Lin− cells were seeded in 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plates at a concentration of one cell per well in 50 μL complete IMDM and predetermined optimal concentrations of cytokines. Four hundred wells were seeded per group. Wells were scored for clonal growth (>10 cells) after 7 to 9 days of incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2 in air. In some experiments, to ensure that the effects observed were on single cells, all wells were visualized by microscopy 2 hours after seeding of the cells, and only the wells containing one cell per well were included in the experiment. Similar results were observed with both methods.

Flow cytometric analysis of Fas expression. Cell-surface expression of Fas was examined on freshly isolated Lin− BM cells from normal mice or thymocytes from normal and lpr/lpr mice. Fas expression was also investigated on Lin− BM cells incubated for different periods of time in complete IMDM with cytokines at predetermined optimal concentrations. FITC-conjugated Jo2 or irrelevant hamster IgG control antibody were used at 0.2 μg in 100 μL medium based on titration of the antibody on thymocytes from normal mice as compared with thymocytes from mice homozygous for lpr which do not bind the Fas Ab.17 32 The cells were incubated with the antibody for 30 minutes on ice after blocking unspecific binding with hamster IgG (10 μg in 100 μL medium; Jackson ImmunoResearch Lab, Inc, West Grove, PA) for 10 minutes. Cells were analyzed for Fas expression by flow cytometry (FACSort; Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Apoptosis assay. Apoptotic cells were detected by a previously described method.37 Briefly, 1 × 106 freshly isolated thymocytes were incubated in RPMI-1640 tissue culture medium (Bio Whittaker, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 10% FCS in the presence or absence of cycloheximide (ICN Biomedicals, Inc, Irvine, CA), or 80,000 Lin− BM cells were incubated in complete IMDM and cytokines in the absence or presence of Jo2. Cells were pelleted in a microcentrifuge, fixed in 1% methanol-free formaldehyde (Polyscience Inc, Warrington, PA) for 15 minutes on ice, pelleted, and resuspended in 70% ethanol and stored at −20°C. Cells were washed once in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Bio Whittaker, Walkersville, MD) containing 1% FCS before being labeled according to the In Situ Death Detection Kit, Fluorescein (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). Cells were resuspended in 45 μL label solution (containing Fluorescein-dUTP and optimized buffer concentrations), of which 10 μL was removed and used as a negative control. To the remaining 35 μL was added 4 μL enzyme solution (containing terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase: TdT). Both samples were incubated for 60 minutes at 37°C. Finally, 300 μL PBS was added and cells were resuspended and analyzed by flow cytometry. The cell samples collected for apoptosis studies were first counted, and the number of viable cells determined by trypan blue exclusion.

Statistical analysis. All results were expressed as mean values ± SEM of data obtained from at least three experiments. The statistical significance of differences between groups (mean values) was determined using the Student's paired t-test.

RESULTS

An agonistic antibody against Fas (Jo2) did not affect GM-CSF–stimulated colony formation of Lin− BM cells (Fig 1) and, as previously shown, TNF-α slightly enhanced GM-CSF–stimulated colony formation in methylcellulose.38 As demonstrated for human CD34+ progenitor cells,22 23 TNF-α induced Fas-responsiveness of GM-CSF–stimulated Lin− progenitor cells, and a similar but less dramatic effect was seen in response to IL-1. Specifically, Jo2 inhibited GM-CSF–stimulated colony formation by 96% in the presence of TNF-α (P < .0001; Fig 1) and by 36% in the presence of IL-1 (P < .05; Fig 1).

Experiments were next performed to investigate whether TGF-β1 could affect the Fas-responsiveness of Lin− BM progenitor cells (Fig 1). In agreement with previous studies, TGF-β1 synergistically enhanced GM-CSF–stimulated colony formation.25 Unlike TNF-α, TGF-β1 did not induce Jo2 responsiveness of GM-CSF–stimulated progenitor cells (Fig 1), but rather potently inhibited the ability of Jo2 to suppress colony formation of GM-CSF + TNF-α–stimulated Lin− progenitors, in that Jo2 reduced the number of GM-CSF + TNF-α–induced colonies to 4 in the absence of TGF-β1 , whereas 60 colonies were formed in the presence of TGF-β1 (P < .01; Fig 1).

To investigate whether the low, but significant fraction (P < .05) of GM-CSF + TNF-α–induced colonies inhibited by Jo2 in the presence of TGF-β1 might be caused by an inhibitory effect of Jo2 occurring before full protective effect of TGF-β1 could be obtained, we next preincubated cells in GM-CSF + TNF-α + TGF-β1 for 48 hours before supplementing the cultures with Jo2. Jo2 added after 48 hours of preincubation had the same inhibitory effect on GM-CSF + TNF-α–stimulated colony formation as when added at initiation of culture (Fig 1). However, when delaying Jo2 addition for 48 hours, no significant effect of Jo2 was observed on GM-CSF + TNF-α + TGF-β1–induced colony formation (Fig 1; P = .1). As for the TNF-α–induced-Fas-responsiveness, 48 hours of preincubation of GM-CSF + IL-1–stimulated Lin− progenitor cells with TGF-β1 blocked Jo2-induced inhibition of colony formation (Fig 1). Thus, TGF-β1 completely abrogates Fas-induced growth suppression of Lin− BM progenitor cells both in response to TNF-α and IL-1.

The inhibitory effect of TGF-β1 on Fas-induced growth suppression of GM-CSF + TNF-α–stimulated colony formation was concentration dependent, with maximum effect observed at 20 ng/mL, and half-maximum stimulation (ED50 ) at 2 ng/mL (Fig 2). Jo2 inhibited GM-CSF + TNF-α–induced colony formation at similar concentrations in the absence and presence of TGF-β1 , with maximum inhibition observed at 0.1 to 0.5 μg/mL (Fig 3). Thus, increasing the Jo2 concentration to 1 μg/mL did not result in enhanced suppression of TGF-β1–supplemented cultures (Fig 3).

To investigate whether the ability of TGF-β1 to block Fas-induced growth suppression of Lin− progenitor cells was directly mediated on the progenitor cells, Lin− BM cells were also seeded at the single cell level. Whereas Jo2 reduced the number of GM-CSF + TNF-α–induced clones by 87% (mean of three experiments; P < .005), no effect of Jo2 could be observed when cells were incubated in the presence of TGF-β1 (including a 48-hour preincubation before addition of Jo2), supporting a direct action of Jo2, as well as TGF-β1 , on the progenitor cells (I.D., S.E.W.J., unpublished observation, 1996).

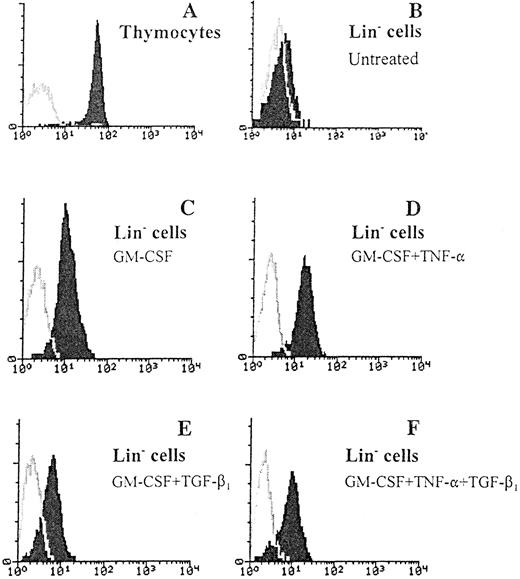

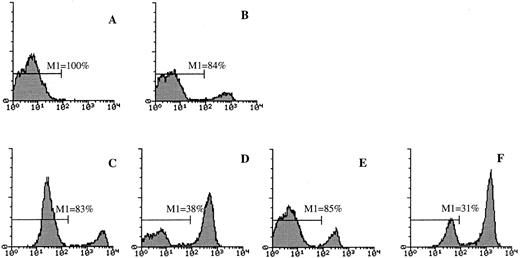

TGF-β1–induced regulation of Fas expression on Lin− BM cells. Fifty thousand Lin− BM cells were cultured in 96-well microtiter plates in complete IMDM and cytokines as indicated at predetermined optimal concentrations for 44 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2 in air. Freshly isolated thymocytes (A), Lin− BM cells (B), as well as cultured Lin− cells (C through F ) were stained with an FITC-conjugated anti-Fas antibody (Jo2) or irrelevant control hamster IgG and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in Materials and Methods. (C and D) Fas expression after culturing Lin− BM cells in GM-CSF for 44 hours, in the absence or presence of TNF-α, respectively. (E and F ) Fas expression of Lin− BM cells cultured in GM-CSF + TGF-β1 after 44 hours of incubation in the absence or presence of TNF-α, respectively. For all panels the Y-axis represents relative cell number and the X-axis represents relative fluorescence intensity. One representative experiment (of three) is shown. Gray lines represent the control antibody.

TGF-β1–induced regulation of Fas expression on Lin− BM cells. Fifty thousand Lin− BM cells were cultured in 96-well microtiter plates in complete IMDM and cytokines as indicated at predetermined optimal concentrations for 44 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2 in air. Freshly isolated thymocytes (A), Lin− BM cells (B), as well as cultured Lin− cells (C through F ) were stained with an FITC-conjugated anti-Fas antibody (Jo2) or irrelevant control hamster IgG and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in Materials and Methods. (C and D) Fas expression after culturing Lin− BM cells in GM-CSF for 44 hours, in the absence or presence of TNF-α, respectively. (E and F ) Fas expression of Lin− BM cells cultured in GM-CSF + TGF-β1 after 44 hours of incubation in the absence or presence of TNF-α, respectively. For all panels the Y-axis represents relative cell number and the X-axis represents relative fluorescence intensity. One representative experiment (of three) is shown. Gray lines represent the control antibody.

The effect of delayed addition of TGF-β1 was next examined to determine whether the potent ability of TGF-β1 to counteract Jo2-induced growth suppression of Lin− progenitors required the presence of TGF-β1 at initiation of culture (Fig 4). A slight reduction in the ability of TGF-β1 to inhibit Jo2-induced growth suppression was observed if the addition of TGF-β1 was delayed 24 hours (P = .2), whereas a 52% reduction in the effect of TGF-β1 (P < .01) was observed if addition was delayed 48 hours. Delayed addition of TGF-β1 for 96 hours completely abrogated the ability of TGF-β1 to counteract Jo2-induced growth suppression. Thus, optimal inhibition of Fas-induced growth suppression by TGF-β1 requires the presence of TGF-β1 from initiation of culture.

As shown by others,17,32 thymocytes expressed high levels of cell-surface Fas (Fig 5A), but, in agreement with previous studies on other cell populations isolated from human BM,22 23 freshly isolated Lin− BM cells expressed low levels of Fas (Fig 5B, Table 1). However, increased Fas expression on Lin− BM cells was observed after as little as 8 hours of incubation in the presence of GM-CSF alone (I.D., S.E.W.J., unpublished observation, 1996). This GM-CSF–induced upregulation of Fas expression reached a maximum after 44 hours of incubation (Fig 5C, Table 1), and 68 hours of incubation in GM-CSF did not further upregulate Fas expression (I.D., S.E.W.J., data not shown). TNF-α further enhanced GM-CSF–induced Fas expression (Fig 5D, Table 1), whereas TGF-β1 reduced the expression of Fas on Lin− BM cells incubated in the presence of GM-CSF or GM-CSF + TNF-α (Fig 5E and F, Table 1). Maximum downregulation of Fas expression was observed at TGF-β1 2 to 20 ng/mL (Table 1).

Effect of TGF-β1 on Fas Expression on Lin− Murine BM Cells

| Cytokines . | Specific Mean Fluorescence Intensity . | Mean Fluorescence, . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Exp 1 . | Exp 2 . | Exp 3 . | % of TGF-β1–Untreated Control (mean of 3 experiments) . |

| None (freshly isolated cells) | 4.2 | 2.8 | 5.8 | NA |

| GM-CSF | 8.6 | 8.5 | 23.9 | 100 |

| GM-CSF + TGF-β1 200 ng/mL | 6.2 | 3.9 | 13.2 | 57 |

| GM-CSF + TGF-β1 20 ng/mL | 6.6 | 4.1 | 12.2 | 56 |

| GM-CSF + TGF-β1 2 ng/mL | 7.5 | 2.5 | 13.1 | 56 |

| GM-CSF + TGF-β1 0.2 ng/mL | 8.5 | 5.9 | 17.6 | 78 |

| GM-CSF + TGF-β1 0.02 ng/mL | 10.5 | 8.6 | ND | 112* |

| GM-CSF + TNF | 13.8 | 13.0 | 37.3 | 100 |

| GM-CSF + TNF + TGF-β1 200 ng/mL | 8.9 | 6.0 | 19.5 | 54 |

| GM-CSF + TNF + TGF-β1 20 ng/mL | 7.3 | 3.6 | 19.1 | 47 |

| GM-CSF + TNF + TGF-β1 2 ng/mL | 10.1 | 5.4 | 23.5 | 61 |

| GM-CSF + TNF + TGF-β1 0.2 ng/mL | 13.8 | 7.3 | 23.6 | 70 |

| GM-CSF + TNF + TGF-β1 0.02 ng/mL | ND | 8.7 | 28.5 | 74* |

| Cytokines . | Specific Mean Fluorescence Intensity . | Mean Fluorescence, . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Exp 1 . | Exp 2 . | Exp 3 . | % of TGF-β1–Untreated Control (mean of 3 experiments) . |

| None (freshly isolated cells) | 4.2 | 2.8 | 5.8 | NA |

| GM-CSF | 8.6 | 8.5 | 23.9 | 100 |

| GM-CSF + TGF-β1 200 ng/mL | 6.2 | 3.9 | 13.2 | 57 |

| GM-CSF + TGF-β1 20 ng/mL | 6.6 | 4.1 | 12.2 | 56 |

| GM-CSF + TGF-β1 2 ng/mL | 7.5 | 2.5 | 13.1 | 56 |

| GM-CSF + TGF-β1 0.2 ng/mL | 8.5 | 5.9 | 17.6 | 78 |

| GM-CSF + TGF-β1 0.02 ng/mL | 10.5 | 8.6 | ND | 112* |

| GM-CSF + TNF | 13.8 | 13.0 | 37.3 | 100 |

| GM-CSF + TNF + TGF-β1 200 ng/mL | 8.9 | 6.0 | 19.5 | 54 |

| GM-CSF + TNF + TGF-β1 20 ng/mL | 7.3 | 3.6 | 19.1 | 47 |

| GM-CSF + TNF + TGF-β1 2 ng/mL | 10.1 | 5.4 | 23.5 | 61 |

| GM-CSF + TNF + TGF-β1 0.2 ng/mL | 13.8 | 7.3 | 23.6 | 70 |

| GM-CSF + TNF + TGF-β1 0.02 ng/mL | ND | 8.7 | 28.5 | 74* |

50,000 Lin− BM cells were cultured for 44 hours in 96-well microtiter plates in complete IMDM in the presence of GM-CSF (20 ng/mL), in the absence or presence of TNF-α (20 ng/mL) and increasing concentrations of TGF-β1 , as indicated. Freshly isolated cells and groups of cultured Lin− cells were stained with an FITC-conjugated anti-Fas antibody (Jo2) or FITC-conjugated irrelevant control hamster IgG. Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry as described in Materials and Methods. For each of three individual experiments, results are displayed as mean specific fluorescence intensity (relative mean fluorescence of control antibody is subtracted from fluorescence obtained with Jo2 antibody). In addition, the fluorescence (mean of three experiments) is expressed as percentage of TGF-β1–untreated control cells. The mean fluorescence intensity of control antibody for various samples varied between 2.5 and 5.7.

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; ND, not determined.

Mean of two experiments.

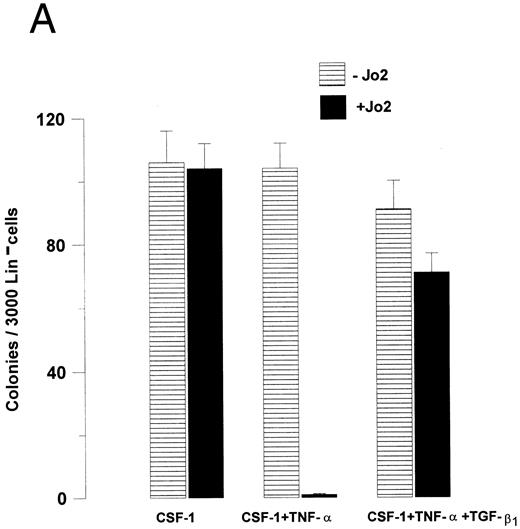

The ability of TGF-β1 to modulate hematopoietic progenitor cell growth has been demonstrated to depend on the specific progenitor cells targeted as well as the specific cytokines stimulating growth.24 25 Thus, to investigate whether the ability of TGF-β1 to abrogate Fas-induced growth suppression was restricted to GM-CSF–responsive progenitor cells, the effect of Jo2 was next investigated on CSF-1–responsive Lin− BM progenitors, thus allowing the study of a different (at least in part) progenitor cell population stimulated by another cytokine. As for GM-CSF–responsive progenitors, CSF-1–induced growth was not affected by the presence of Jo2 in the absence of TNF-α, whereas a 99% reduction in CSF-1–induced colony formation was observed in the presence of TNF-α (P < .0001), and again TGF-β1 almost completely blocked Jo2-induced growth suppression (P < .01; Fig 6A). Also, when Lin− cells were stimulated with a potent cocktail of cytokines (CSF-1 + GM-CSF + IL-3 + IL-6 + SCF ), TGF-β1 was capable of completely abrogating Jo2-induced growth suppression in the presence of TNF-α (P < .001; Fig 6B).

TGF-β1 abrogates Fas-induced growth suppression of Lin− BM progenitors responsive to CSF-1 as well as a combination of multiple cytokines. (A) 3,000 or (B) 1,000 Lin− BM cells were preincubated for 48 hours in IMDM containing 20% FCS, 1.2% methylcellulose and CSF-1 (A), or a “cocktail” of cytokines (CSF-1 + GM-CSF + IL-3 + IL-6 + SCF; B) in the presence or absence of TNF-α and/or TGF-β1 , as indicated. 0.5 μg/mL Jo2 was added after 48 hours of incubation, as indicated. Colonies were scored after 7 to 9 days of incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2 in air. An irrelevant hamster IgG had no effect on colony formation. Results represent the mean values of three separate experiments with duplicate determinations; error bars show the SEM.

TGF-β1 abrogates Fas-induced growth suppression of Lin− BM progenitors responsive to CSF-1 as well as a combination of multiple cytokines. (A) 3,000 or (B) 1,000 Lin− BM cells were preincubated for 48 hours in IMDM containing 20% FCS, 1.2% methylcellulose and CSF-1 (A), or a “cocktail” of cytokines (CSF-1 + GM-CSF + IL-3 + IL-6 + SCF; B) in the presence or absence of TNF-α and/or TGF-β1 , as indicated. 0.5 μg/mL Jo2 was added after 48 hours of incubation, as indicated. Colonies were scored after 7 to 9 days of incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2 in air. An irrelevant hamster IgG had no effect on colony formation. Results represent the mean values of three separate experiments with duplicate determinations; error bars show the SEM.

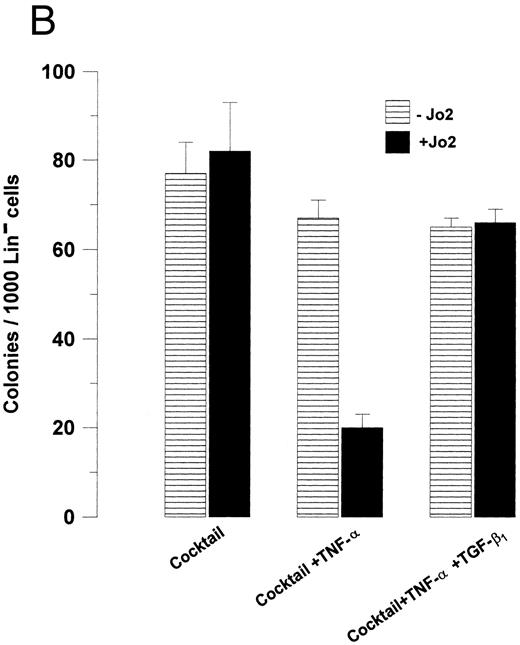

The ability of Jo2 to induce growth suppression of GM-CSF + TNF-α–stimulated Lin− BM cells (Fig 1) was accompanied by enhanced apoptosis (P < .01; Fig 7) and, in agreement with its ability to abrogate Fas-induced growth suppression, TGF-β1 also blocked Jo2-induced apoptosis (P < .05; Fig 7). Similarly, Jo2 reduced the number of viable cells by 50% in the presence TNF-α (P < .005; mean of three experiments), whereas no reduction was observed in the presence of TGF-β1 (P = .7) (I.D., S.E.W.J., unpublished observation, 1996).

TGF-β1 inhibits Jo2-induced apoptosis of Lin− BM cells. Eighty thousand Lin− BM cells were cultured for 52 hours in 96-well microtiter plates in complete IMDM supplemented with cytokines as indicated. For the last 22 hours cultures were continued in the absence () or presence (▪) of 1 μg/mL Jo2. Cultures were analyzed for apoptotic cells as described in Materials and Methods. Freshly isolated Lin− BM cells contained less than 1% apoptotic cells (data not shown). An irrelevant hamster IgG control antibody (1 μg/mL) did not affect apoptosis or cell numbers (data not shown). Results represent the mean values of three independent experiments. Error bars show the SEM.

TGF-β1 inhibits Jo2-induced apoptosis of Lin− BM cells. Eighty thousand Lin− BM cells were cultured for 52 hours in 96-well microtiter plates in complete IMDM supplemented with cytokines as indicated. For the last 22 hours cultures were continued in the absence () or presence (▪) of 1 μg/mL Jo2. Cultures were analyzed for apoptotic cells as described in Materials and Methods. Freshly isolated Lin− BM cells contained less than 1% apoptotic cells (data not shown). An irrelevant hamster IgG control antibody (1 μg/mL) did not affect apoptosis or cell numbers (data not shown). Results represent the mean values of three independent experiments. Error bars show the SEM.

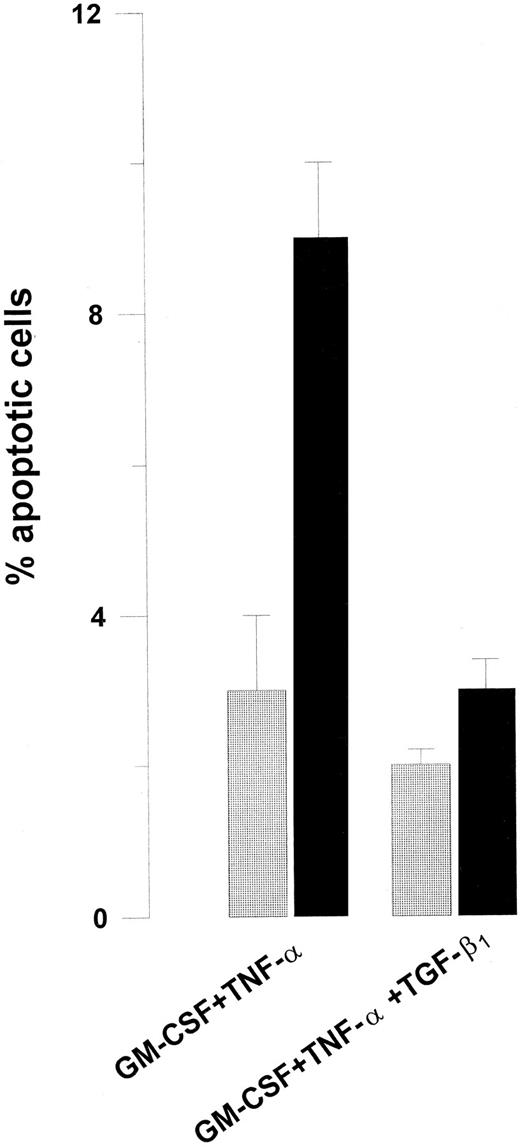

It was of interest to determine whether TGF-β1 might also protect murine thymocytes from Fas-induced apoptosis, because Fas activation potently induces their apoptosis in the absence of a coactivation signal.32 However, unlike its ability to protect Lin− BM cells from Jo2-induced growth suppression and apoptosis, TGF-β1 had no effect on Fas-induced apoptosis of murine thymocytes (Fig 8).

The effect of TGF-β1 on Jo2-induced apoptosis of murine thymocytes. 1 × 106 freshly isolated thymocytes (A) were cultured for 9 hours in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FCS (B) or in medium supplemented with 30 μg/mL cycloheximide in the absence or presence of 2 μg/mL Jo2 (C and D, respectively) or in cycloheximide-containing medium supplemented with TGF-β1 in the absence and presence of Jo2 (E and F, respectively). Cultures were analyzed for apoptotic cells as described in Materials and Methods. An irrelevant hamster IgG control antibody (2 μg/mL) did not affect apoptosis (data not shown). The Y-axis represents relative cell number and the X-axis represents relative fluorescence index. M1 represents percentage of viable cells. One representative experiment (of three) is shown.

The effect of TGF-β1 on Jo2-induced apoptosis of murine thymocytes. 1 × 106 freshly isolated thymocytes (A) were cultured for 9 hours in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FCS (B) or in medium supplemented with 30 μg/mL cycloheximide in the absence or presence of 2 μg/mL Jo2 (C and D, respectively) or in cycloheximide-containing medium supplemented with TGF-β1 in the absence and presence of Jo2 (E and F, respectively). Cultures were analyzed for apoptotic cells as described in Materials and Methods. An irrelevant hamster IgG control antibody (2 μg/mL) did not affect apoptosis (data not shown). The Y-axis represents relative cell number and the X-axis represents relative fluorescence index. M1 represents percentage of viable cells. One representative experiment (of three) is shown.

DISCUSSION

Fas and its ligand are critically involved in regulation of the immune system.11 Recent studies on human CD34+ BM progenitor cells showed that Fas expression can be induced in response to proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IFN-γ, upon which activation of Fas can result in growth suppression and apoptosis.22 23 Using a population of enriched Lin− BM progenitor cells, we show here that activation of these progenitor cells by CSFs results in upregulation of Fas expression, but that such expression is insufficient to allow triggering of growth suppression through activation of Fas. However, the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α (and in part IL-1) can provide a coactivation signal that appears necessary for Fas-induced growth suppression and apoptosis of murine progenitor cells.

Because enhanced expression of proinflammatory cytokines and Fas activation are thought to be involved in BM failure syndromes,21 and because TGF-β1 has been shown to represent a nonredundant and essential anti-inflammatory cytokine,28 29 we here addressed whether TGF-β1 might act to oppose Fas-induced progenitor cell suppression.

In the absence of TGF-β1 but in the presence of TNF-α, Jo2 almost completely blocked colony formation of Lin− BM progenitors in response to GM-CSF, but in the presence of TGF-β1 this Fas response was potently inhibited. Single-cell cloning and delayed addition experiments suggested that the effect of Fas as well as TGF-β1 occurred at an early stage and directly on the progenitor cells, and not indirectly through potentially contaminating accessory cells.

A 48-hour preincubation with TGF-β1 was required to completely abrogate Fas-induced growth suppression of Lin− progenitor cells in the presence of TNF-α, suggesting that the protective effect of TGF-β1 requires longer time to occur than Fas-induced suppression. Also, Fas-induced suppression of GM-CSF–induced growth observed in the presence of IL-1 was completely abrogated by TGF-β1 . Furthermore, the ability of TGF-β1 to protect Lin− progenitors from Fas-induced growth suppression was not restricted to GM-CSF–responsive Lin− BM progenitor cells, because TGF-β1 also potently blocked Fas-induced growth suppression of CSF-1–responsive Lin− progenitors as well as those stimulated by a combination of multiple cytokines. It is noteworthy that TGF-β1 under all these culture conditions, in the absence of Jo2, delivered either a growth-stimulatory effect (in the presence of GM-CSF ) or had no growth-modulatory effect. This was in agreement with the notion that the ability of TGF-β1 to inhibit progenitor cell growth is predominantly restricted to primitive progenitor/stem cells.24 25 Thus, it would be important if one could determine whether TGF-β1–induced inhibition of Fas-induced apoptosis also includes progenitor cells subject to TGF-β1–induced growth inhibition. Such experiments are in progress in our laboratory, but so far we have found little or no protective effect of TGF-β1 on Fas-induced growth suppression of progenitor cells sensitive to TGF-β1–induced growth inhibition (F.G., S.E.W.J., unpublished observations, 1996). Consequently, one interpretation might be that the ability of TGF-β1 to inhibit Fas-induced growth suppression is restricted to progenitors insensitive to growth-inhibitory effects of TGF-β1 . Alternatively, it might rather reflect technical obstacles, because TGF-β1 itself almost completely inhibits the growth of such progenitors, thus masking any potential inhibition of Fas-induced growth suppression. Although the ability of TGF-β1 to protect primitive progenitor cells from Fas-induced apoptosis remains to be characterized, the present studies show that progenitor cells insensitive to TGF-β1–induced inhibition display a distinct and strong TGF-β1 responsiveness, resulting in resistance toward Fas-induced growth suppression and apoptosis. Thus, on the investigated progenitor cells, the ability of TGF-β1 to block Fas-induced progenitor cell suppression is distinct from its ability to keep hematopoietic progenitors out of cell cycle.

The ability of TGF-β1 to counteract Fas-induced growth suppression was reflected in reduced apoptosis in the TGF-β1–treated cultures. However, for the TGF-β1–untreated cultures, the fraction of apoptotic cells detected in response to Fas was quite low as compared with the reduction in viable cells observed in the same cultures. It cannot be ruled out that the reason for this could be that Fas might (at least in part) be acting through a nonapoptotic mechanism mediating growth suppression. However, this seems unlikely based on the dramatic and rapid reduction in number of viable cells in response to Fas activation, the fact that Fas-induced growth suppression was almost completely irreversible, and previous studies showing that apoptotic progenitor cells rapidly undergo secondary necrosis and disintegrate in in vitro cultures.5 6

TGF-β1 has been shown to potently modulate the expression of numerous cytokine receptors,39-41 and we here demonstrate that TGF-β1 also downregulates Fas expression on Lin− BM cells, suggesting that TGF-β1 might be inhibiting Fas-induced signaling (at least in part) through reduction of available Fas. However, because the effect on Fas expression was rather modest compared with the potent inhibition of Fas-induced growth suppression, it appears likely that TGF-β1 might also affect downstream signaling through Fas. In addition or alternatively, TGF-β1 might be interacting with TNF-α–induced signaling, which was essential for triggering of growth suppression through Fas. Thus, further studies on the ability of TGF-β1 to affect Fas– and TNF-α–induced signaling would be of considerable interest.

In contrast to its ability to abrogate Fas-induced growth suppression and apoptosis of BM progenitors, TGF-β1 had no effect on Fas-induced apoptosis of freshly isolated murine thymocytes. This was probably not due to the incubation with TGF-β1 lasting for only 9 hours, because as much as 30 hours of TGF-β1 (including preincubation in the absence of Jo2) treatment had no effect on Fas-induced apoptosis of thymocytes (I.D., S.E.W.J., unpublished observation, 1996). Interestingly, the triggering of apoptosis of murine thymocytes through Fas does not, unlike the progenitor cells, require a coactivation signal.32 Thus, the distinct ability of TGF-β1 to protect murine myeloid progenitor cells but not thymocytes from Fas-induced apoptosis might potentially be a consequence of TGF-β1 interacting with the coactivation (TNF ) signal rather than Fas signaling. In support of this, a recent study showed that TGF-β1 can inhibit Fas-induced apoptosis of phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-activated human T cells.42 Thus, TGF-β1 might specifically act to limit activation-dependent Fas-induced apoptosis. This could be of physiological relevance, in particular for the hematopoietic stem cells which are present at limited numbers and which have been suggested to produce TGF-β1 in an autocrine manner.26,27 Such TGF-β1 production might act not only to keep hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells from cycling, but also to protect them from Fas-induced apoptosis under conditions of enhanced production of proinflammatory cytokines. Thus, dysregulated TGF-β1 production or responsiveness might potentially be involved in the enhanced Fas activation observed in BM failure such as that observed in aplastic anemia.21 Accordingly, TGF-β1 or less toxic analogs might be of benefit to patients suffering from BM failure associated with enhanced Fas activation.

The present finding is in contrast to a recent study suggesting that TGF-β1 can enhance Fas-induced apoptosis of human glioma cells.43 This could be due to TGF-β1 having a differential effect on Fas-induced apoptosis of normal and malignant cells, or might simply reflect the pleiotropic nature of TGF-β1 actions.30,31 The present results, combined with other recent studies showing that TGF-β1 can rather enhance progenitor cell apoptosis in vitro,5,6 implicate TGF-β1 as a bidirectional regulator of apoptosis in the hematopoietic system. The reason for this is not clear. However, in settings in which TGF-β has been shown to rather promote apoptosis, it is believed (at least in part) to act through inhibition of essential viability-promoting signals for nonproliferative primitive progenitor cells, such as those mediated through c-kit.6 Thus, the ability of TGF-β1 to enhance or suppress apoptosis could depend on the specific progenitor cells targeted or the cytokines/signals interacting with TGF-β1 . Such determinants have been implicated to be of importance for determining whether TGF-β1 will inhibit, stimulate, or have no effect on hematopoietic progenitor cell growth and differentiation.24 In that regard, the present findings further underscore the pleiotropic hematopoietic activities of TGF-β1 , a finding worthy of additional mechanistic studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Heide Kammer for assistance with isolation of BM cells, and AlphaMed Press (Dayton, OH) for preparation of figures.

Supported by Sør-Trøndelag Fylkeskommune, The Norwegian Cancer Society, Ohio Cancer Research Associates, and The Swedish Cancer Society.

Address reprint requests to Sten Eirik W. Jacobsen, MD, PhD, Stem Cell Laboratory, Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital of Lund, 221 85 Lund, Sweden.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal