Abstract

Glycoprotein (GP) Ib is an adhesion receptor on the platelet surface that binds to von Willebrand Factor (vWF). vWF becomes attached to collagens and other adhesive proteins that become exposed when the vessel wall is damaged. Several investigators have shown that during cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) surgery and also during platelet activation in vitro by thrombin or thrombin receptor activating peptide (TRAP) GPIb disappears from the platelet surface. Such a disappearance is presumed to lead to a decreased adhesive capacity. In the present study, we show that a 65% decrease in platelet surface expression of GPIb, due to stimulation of platelets in Orgaran anticoagulated whole blood with 15 μmol/L TRAP, had no effect on platelet adhesion to both collagen type III and the extracellular matrix (ECM) of human umbilical vein endothelial cells under flow conditions in a single-pass perfusion system. In contrast to adhesion, ristocetin-induced platelet agglutination was highly dependent on the presence of GPIb. Immunoelectron microscopic studies showed that GPIb almost immediately returned to the platelet surface once platelets had attached to collagen. In a subsequent series of experiments, we showed that when less than 50% of GPIb was blocked by an inhibitory monoclonal antibody against GPIb (6D1), platelet adhesion under flow conditions remained unaffected.

GLYCOPROTEIN (GP) Ib is unique for human platelets. It is present as a transmembrane protein in the plasma membrane, approximately 25,000 copies per platelet. GPIb consists of two polypeptide chains, an α and β-chain of molecular weight (MW) 150 kD and 27 kD, respectively. The α-chain is glycosylated and sensitive to proteolysis by proteases such as plasmin1 and cathepsin G in vitro.2 GPIb functions as a receptor for von Willebrand Factor (vWF) and the vWF-GPIb interaction plays a key role in the adhesion under flow conditions to collagen,3 fibronectin,4 and fibrinogen.5 In addition, GPIb is a high-affinity receptor for α-thrombin.6 7

When platelets are stimulated in vitro by α-thrombin, or thrombin receptor activating peptide (TRAP), the expression of GPIb on the platelet surface decreases. This decrease is due to a cytoskeletal-mediated redistribution to the open canalicular system (OCS), where it is inaccessible to antibodies.8-11 The decrease in the platelet surface expression of GPIb is reversible, as has been shown for platelets stimulated by α-thrombin, where fully functional GPIb reappeared on the platelet surface after an initial disappearance.12 At present, however, it is unknown whether the diminished platelet surface expression of GPIb has any consequences for platelet adhesion under flow.

Also the in vivo expression of GPIb on the platelet surface is variable. Five minutes after the start of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), during which time blood had contacted the artificial surface of the extracorporeal system, the surface expression of GPIb decreased by 30% to 40%.13,14 These findings received much attention, as prolonged bleeding times and excessive blood loss often occur during and after CPB. A diminished surface expression of GPIb may lead to a reduced ability of platelets to adhere to the damaged vessel wall, and this may result in prolonged bleeding times and excessive blood loss. This model was supported by the finding that patients undergoing CPB surgery who received aprotinin (trasylol), a nonspecific inhibitor of serine proteases, showed no disappearance of GPIb and lost less blood.13,15 16

However, this model is in contrast with the observation that carriers of the inherited disease Bernard-Soulier Syndrome, which have half the normal number of GPIb copies on their platelets, do not bleed.17 18

The aim of the present study was to investigate the relationship between platelet adhesion under flow and the presence of GPIb on the platelet surface. Whole blood was anticoagulated with Orgaran and stimulated with TRAP in the presence of dRGDW to avoid platelet aggregation. The advantage of platelet stimulation by TRAP was that we were able to study the effect of GPIb downregulation in whole blood under physiologic Ca2+ levels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Adhesive surfaces.

Human placenta collagen type III was obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO) and solubilized in 50 mmol/L acetic acid (1.4 mg/mL). The solubilized collagen was sprayed onto glass coverslips (Menzel, Braunschweig, Germany) with a retouching airbrush (Badger model 100, Badger Brush Co, Franklin Park, IL) to a surface density of 30 μg cm-2, supporting optimal platelet coverage.19 The amount of collagen deposited on the coverslips was determined by weighting the coverslips before and after spraying.

Human vascular endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins were isolated according to Jaffe et al20 with some modifications.21 The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 containing 20% pooled human serum. Endothelial cells of the third passage were used. After the cells had grown to confluence on glass coverslips, matrices were isolated by exposing the cells to 0.1 mol/L NH4OH.22 This step was followed by three washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS: 10 mmol/L sodium phosphate, 150 mmol/L NaCl, pH 7.4).

Both the coverslips with collagen and extracellular matrix (ECM) were subsequently blocked by incubation with a 1% human albumin solution (Behringwerke, Marburg, Germany) in HEPES-buffered saline (HBS: 10 mmol/L Hepes, 150 mmol/L NaCl, pH 7.35), for 30 minutes at room temperature.

Reagents.

The D-arginyl-glycyl-L-aspartyl-L-tryptophan (dRGDW) peptide was generously provided by Dr J. Bouchaudon (Rhône-Poulenc-Rorer, Chemistry Department, Centre de Recherche de Vitry, Vitry sur Seine, France). The preincubation period of the dRGDW peptide was 15 minutes.

The thrombin-receptor activating peptide TRAP (SFLLRN) was obtained from Bachem Feinchemikalien AG (Bubendorf, Switzerland).

Monoclonal antibody (MoAb) 6D1, an inhibitory MoAb directed against GPIb, was kindly provided by Dr B. Coller23 (Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY). The MoAb was used as ascites and was added to the perfusate 30 minutes before perfusion.

Flow cytometry.

Fixed platelets were prepared by collecting 1 volume of blood in 5 vol of paraformaldehyde in PBS (final concentration, 1%). Platelets were washed twice with PBS to which 5 mmol/L EDTA had been added (PBS/EDTA) and diluted to a concentration of 3.108/mL.

A total of 10 μL of platelet suspension was incubated with 10 μL fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated monoclonal antibody (5 μg/mL) for 30 minutes at room temperature. MoAb 6.20 (obtained from Dr H.K. Nieuwenhuis, Department of Hematology, University Hospital Utrecht) is a noninhibitory antibody directed against GPIb (tested in ristocetin-induced platelet agglutination). This MoAb reacts with the GPIb α-band in a Western blot and was completely negative in cytofluorography with platelets of a patient with the Bernard Soulier syndrome. The occupation of GPIb by the inhibitory MoAb 6D1 was determined by using a secondary FITC-conjugated goat antimouse antibody and calculated as percentage of saturation.

FITC-conjugated CD62 MoAb RUU-SP 2.1724 directed against P-selectin was used to detect P-selectin on the platelet surface after platelets were activated by TRAP.

We used control ascites or a control IgG against an antigen that is not present on platelets.

After washing, the platelets were resuspended in 2 mL PBS for analysis. Platelets were analyzed in a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) at a wavelength of 488 nm.24 FACScan data were analyzed with PC-LYSIS software (Becton Dickinson).

Ristocetin-induced platelet agglutination (RIPA).

For RIPA, platelets were prepared as described by Brinkhous and Read.25 Washed platelets were incubated with 200 μmol/L dRGDW and were subsequently incubated for various periods of time (0 to 60 minutes) with 15 μmol/L TRAP at 37°C. After the incubation with TRAP, the platelets were fixed in 1.8% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes, washed three times, and resuspended in citrated saline with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma) to a final concentration of 8 × 108/μL. A total of 100 μL fixed platelets was mixed with 325 μL Tris buffer (10 mmol/L Tris, 150 mmol/L NaCl, pH 7.35) containing 0.5% BSA and 25 μL ristocetin (20 mg/mL; Diamed, Cressier sur Morat, Switzerland), and incubated for 2 minutes at 37°C. The agglutination was triggered by the addition of 50 μL pooled normal plasma and measured in a Chronolog lumiaggregometer at 37°C with stirring at 900 rpm.

Perfusions.

Fresh blood from healthy donors who denied having taken aspirin in the preceding 10 days was anticoagulated with one tenth volume of 150 U/mL Orgaran (a low molecular weight heparinoid [LMWH]; Organon, Oss, the Netherlands). A total of 200 μmol/L of the dRGDW peptide was added to the anticoagulated blood to avoid platelet aggregation. Perfusions were performed in modified parallel plate perfusion chambers with a slit height of 0.1 mm and a slit width of 2 mm,26 corresponding with flow rates of 60 μL/min (shear rate = 300 s-1) and 320 μL/min (shear rate = 1,600 s-1). Blood was prewarmed at 37°C for 10 minutes and was then drawn through 6 parallel perfusion chambers by a Harvard infusion pump (pump 22, model 2400-004; Natick, MA). At the onset of perfusion, blood samples were drawn and immediately fixed for flow cytometry or for immunoelectron microscopy.

After each perfusion run, the coverslips were removed from the perfusion chambers and rinsed with HBS, fixed in glutaraldehyde (0.5% in PBS) and stained with May Grünwald/Giemsa as described.27 Platelet adhesion was quantitated with a light microscope (at 1,000× magnification) coupled to a computerized image analyzer (AMS 40-10, Saffron Walden, UK). Three lines perpendicular to the flow direction were evaluated: one line in the center of the coverslip and two lines 3 mm to the right and 3 mm to the left of the center. Platelet adhesion was expressed as the percentage of the surface covered with platelets.

Immunoelectron microscopy.

The expression of GPIb on the platelet surface immediately before the start of perfusion was compared with the expression of GPIb on the platelet surface after adhesion to collagen type III-coated coverslips. For the latter, collagen was sprayed on melamin-coated coverslips.28 Briefly, glass coverslips were coated with melamin by dipping in a 1% melamin solution, containing 0.3% paratoluene sulfonic acid, dissolved in analytical grade ethanol. The coverslips were carefully withdrawn and immediately flamed for polymerization.

Blood samples and perfused coverslips were fixed in a mixture of 2% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). After rinsing with PBS/0.15 mmol/L glycine, the melamin foil was removed from the glass coverslips with 0.8% hydrofluoric acid at 4°C.

The melamin foils were used for ultrathin cryosectioning and transmission electron microscopy (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). Immunogold labeling was performed on thin frozen sections of platelets in suspension and adhering platelets, using MoAb AK3 (generously provided by Dr M.C. Berndt, Prahran, Australia29) followed by a rabbit antimouse IgG (DAKOpatts, Glostrup, Denmark) intermediate step, and finally with protein-A-gold (10 nm). The specificity of immunolabeling was verified using an irrelevant control antibody. Quantification was performed on randomly photographed platelet profiles by counting the number of gold particles on the plasma membrane (PM), the membranes of the open canalicular system (OCS), α-granules, and nondefined structures. The data are expressed as percentages of the total number of gold particles counted and represent the mean of at least three separate immunolabeling experiments. The total numbers of platelets counted were 70 (control) and 81 (TRAP stimulated) for the platelets in suspension and 69 (control) and 63 (TRAP stimulated) for the adhered platelets.

Statistical analysis.

Student's t-test was used to test for differences between groups. P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

In a preliminary set of experiments, the effect of various concentrations of TRAP (0 to 15 μmol/L) on the disappearance of the GPIb-antigen was analyzed by flow cytometry. Whole blood was anticoagulated with Orgaran in the presence of 200 μmol/L dRGDW. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of GPIb decreased by approximately 60% when platelets were stimulated with 10 μmol/L or 15 μmol/L TRAP, 5 minutes after the addition of the agonist (Fig 1). The observed decrease in the platelet surface expression of GPIb was accompanied by an increase in P-selectin on the platelet surface. P-selectin is present on the membranes of α-granules and is expressed on the platelet surface after platelets are activated and release their α-granules.30 The downregulation of GPIb and the surface expression of P-selectin are not coupled because the decrease in GPIb is not dependent on the release of α-granules, and the restoration of the surface expression of GPIb can occur in a fully degranulated platelet.12

Effect of different concentrations of TRAP on the platelet surface expression of GPIb and P-selectin. Orgaran anticoagulated whole blood (+ dRGDW) was incubated (5 minutes, 37°C) with various concentrations of TRAP. After 5 minutes, the blood was fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde, incubated with either MoAb 6.20 (against GPIb [▴]) or CD62 MoAb RUU-SP 2.17 (against P-selectin [•]), and analyzed by flow cytometry. Both the binding of the anti-GPIb MoAb before the addition of TRAP and the maximal binding of the anti-CD62 MoAb was assigned 100 arbitrary units of fluorescence. Data represent a typical experiment.

Effect of different concentrations of TRAP on the platelet surface expression of GPIb and P-selectin. Orgaran anticoagulated whole blood (+ dRGDW) was incubated (5 minutes, 37°C) with various concentrations of TRAP. After 5 minutes, the blood was fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde, incubated with either MoAb 6.20 (against GPIb [▴]) or CD62 MoAb RUU-SP 2.17 (against P-selectin [•]), and analyzed by flow cytometry. Both the binding of the anti-GPIb MoAb before the addition of TRAP and the maximal binding of the anti-CD62 MoAb was assigned 100 arbitrary units of fluorescence. Data represent a typical experiment.

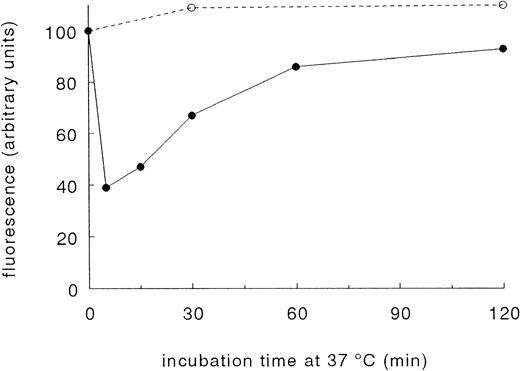

When blood at 37°C was stimulated with an optimal concentration of 15 μmol/L TRAP, GPIb disappeared from the platelet surface within 5 minutes. After 5 minutes, GPIb started to reappear on the cell surface, and after 60 minutes, approximately 80% of the baseline value was found (Fig 2). A slight increase in GPIb was noticed in parallel experiments in which no TRAP was added. This increase probably refers to platelet activation during blood collection. dRGDW did not interfere with the binding of the MoAbs tested (data not shown).

Reversibility of the TRAP-induced decrease of the platelet surface expression of GPIb. A total of 15 μmol/L TRAP (•) was added at t = 0 minutes to Orgaran anticoagulated whole blood (+ dRGDW) at 37°C. As a control, no agonist (○) was added. The samples were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde at the indicated time points. The binding of the GPIb-specific MoAb 6.20 at t = 0 minutes (before TRAP was added) was assigned 100 arbitrary units of fluorescence. Data are the mean of two separate experiments.

Reversibility of the TRAP-induced decrease of the platelet surface expression of GPIb. A total of 15 μmol/L TRAP (•) was added at t = 0 minutes to Orgaran anticoagulated whole blood (+ dRGDW) at 37°C. As a control, no agonist (○) was added. The samples were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde at the indicated time points. The binding of the GPIb-specific MoAb 6.20 at t = 0 minutes (before TRAP was added) was assigned 100 arbitrary units of fluorescence. Data are the mean of two separate experiments.

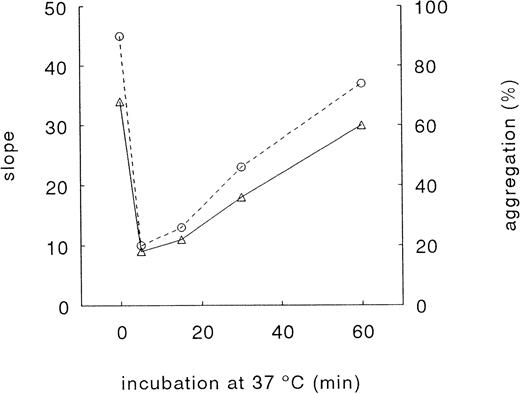

The TRAP-induced decrease in platelet surface expression of GPIb was accompanied by a decrease in RIPA (Fig 3). After 5 minutes, a time-dependent recovery in RIPA was observed. The results presented in Fig 3 show that RIPA is highly dependent on the platelet surface expression of GPIb.

Effect of TRAP on RIPA. Washed platelets were incubated with 15 μmol/L TRAP at 37°C and fixed with paraformaldehyde at the indicated time points. The RIPA without agonist was assigned 100%. Agglutination was triggered by pooled normal plasma and 1 mg/mL ristocetin (see Materials and Methods). % agglutination (○); slope of curve (▵). Data represent a typical experiment.

Effect of TRAP on RIPA. Washed platelets were incubated with 15 μmol/L TRAP at 37°C and fixed with paraformaldehyde at the indicated time points. The RIPA without agonist was assigned 100%. Agglutination was triggered by pooled normal plasma and 1 mg/mL ristocetin (see Materials and Methods). % agglutination (○); slope of curve (▵). Data represent a typical experiment.

To determine the effect of GPIb downregulation on platelet adhesion under flow conditions, whole blood, anticoagulated with Orgaran was stimulated with 15 μmol/L TRAP or vehicle at 37°C, in the presence of dRGDW. As previously shown,31 32 dRGDW has no inhibitory effect on platelet adhesion to collagen type III and ECM when LMWH is used as anticoagulant.

Five minutes after the addition of TRAP, samples were removed for flow cytometry analysis. Immediately thereafter, six parallel single-pass perfusion runs were started at 37°C over coverslips with either collagen type III or ECM (three runs with TRAP, three runs without agonist). TRAP induced a disappearance of GPIb from the platelet surface in all donors tested. The overall decrease was 65% (mean ± standard error of mean [SEM] = 35% ± 1.7% of control, n = 12). As shown in Table 1, the adhesion of TRAP-stimulated platelets at a shear rate of 1,600 s-1 was not significantly different from unstimulated platelets, both to collagen type III and ECM. Under the present conditions (ie, with the addition of dRGDW), we did not observe differences in spreading between TRAP-stimulated and control platelets adhered to collagen or ECM. Similar results were obtained with collagen type III at a shear rate of 300 s-1 (data not shown), indicating that this effect was independent of the shear stress applied to the platelets. Thus, a decrease of approximately 65% in platelet surface expression of GPIb has no effect on platelet adhesion under the conditions tested.

Effect of 15 μmol/L TRAP on Platelet Adhesion to Collagen Type III and to the ECM of Endothelial Cells at a Shear Rate of 1,600 s−1

| Adhesive Surface . | Platelet Adhesion (%) . | |

|---|---|---|

| Control . | +TRAP . | |

| Collagen type III | 29.2 ± 2.8 | 27.9 ± 3.0 NS |

| Range, 19.3-41.0 | Range, 13.4 − 38.9 | |

| ECM | 22.5 ± 2.4 | 23.4 ± 3.6 NS |

| Range, 15.9-26.7 | Range, 15.5-32.7 | |

| Adhesive Surface . | Platelet Adhesion (%) . | |

|---|---|---|

| Control . | +TRAP . | |

| Collagen type III | 29.2 ± 2.8 | 27.9 ± 3.0 NS |

| Range, 19.3-41.0 | Range, 13.4 − 38.9 | |

| ECM | 22.5 ± 2.4 | 23.4 ± 3.6 NS |

| Range, 15.9-26.7 | Range, 15.5-32.7 | |

Data are obtained in 8 (collagen type III) or in 4 (ECM) independent experiments with blood from different donors (mean ± SEM). A paired t-test was used to test for differences between groups.

Abbreviation: NS, not statistically significant compared with control.

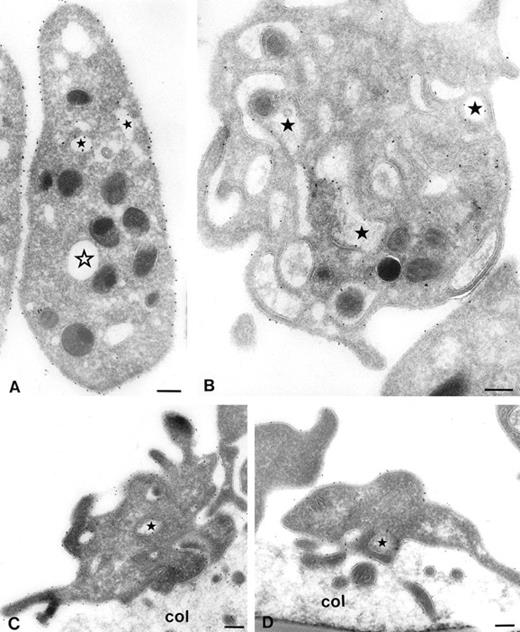

However, it is not clear whether adherent platelets behave identical to platelets in suspension. Once attached to an adhesive surface, it is possible that GPIb, which had disappeared from the platelet surface, becomes mobilized and then participates in platelet adhesion. Therefore immunoelectron microscopic studies were performed. Platelets were stimulated with 15 μmol/L TRAP or vehicle at 37°C. Five minutes after the addition of TRAP, samples were removed for electron microscopy. Immediately thereafter perfusions were started for 5 minutes over collagen type III (shear rate = 1,600 s-1). As shown in Fig 4A, gold particles labeling GPIb are predominantly present on the platelet surface. After stimulation with TRAP, most gold particles are present in the OCS (Fig4B). The relative surface expression of GPIb was quantified by counting the gold particles associated with platelet surface membranes, OCS membranes, α-granules, and undefined structures (Table 2). The percentage of GPIb on the platelet surface of unstimulated platelets was 69.0% ± 2.9% (mean ± SEM, n = 4). After stimulation with TRAP, the percentage of GPIb on the platelet surface was 35.5% ± 2.5% (mean ± SEM, n = 4), representing a 50% decrease in platelet surface GPIb.

Series of electron micrographs showing platelets in suspension (A and B) and adhered platelets to collagen type III (C and D). Whole blood anticoagulated with Orgaran in the presence of dRGDW was stimulated with 15 μmol/L TRAP (B and D) or vehicle (A and C) at 37°C. After 5 minutes, blood samples were drawn, immediately fixed, and used for immunoelectron microscopy (A and B), and perfusions were started for 5 minutes at a shear rate of 1,600 s-1 over coverslips coated with collagen type III. Perfused coverslips were also immediately fixed and used for immunoelectron microscopy (C and D). Immunolabeling was performed on frozen thin sections with MoAb AK3 and 10 nm protein-A gold. Closed stars represent the OCS with gold particles. Open star represents OCS without gold particles. Col, collagen. Bar, 200 nm.

Series of electron micrographs showing platelets in suspension (A and B) and adhered platelets to collagen type III (C and D). Whole blood anticoagulated with Orgaran in the presence of dRGDW was stimulated with 15 μmol/L TRAP (B and D) or vehicle (A and C) at 37°C. After 5 minutes, blood samples were drawn, immediately fixed, and used for immunoelectron microscopy (A and B), and perfusions were started for 5 minutes at a shear rate of 1,600 s-1 over coverslips coated with collagen type III. Perfused coverslips were also immediately fixed and used for immunoelectron microscopy (C and D). Immunolabeling was performed on frozen thin sections with MoAb AK3 and 10 nm protein-A gold. Closed stars represent the OCS with gold particles. Open star represents OCS without gold particles. Col, collagen. Bar, 200 nm.

Percentage of Gold Particles on the PM, the Membranes of the OCS, α-Granules, and Nondefined Structures (undefined) of Unstimulated and TRAP-Stimulated Platelets in Suspension and After Platelet Adhesion to Collagen Type III Under Flow Conditions

| Percentage of Gold Particles . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platelets . | Treatment . | PM . | OCS . | α-Granules . | Undefined . |

| Suspension | Control | 69.0 ± 2.9 | 24.7 ± 2.4 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.6 |

| Suspension | TRAP | 35.5 ± 2.5* | 57.9 ± 2.4* | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 0.2 |

| Adhered | Control | 64.4 ± 3.7 | 31.1 ± 2.8 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 1.2 |

| Adhered | TRAP | 62.0 ± 4.5 NS | 34.2 ± 3.5 NS | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 1.4 |

| Percentage of Gold Particles . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platelets . | Treatment . | PM . | OCS . | α-Granules . | Undefined . |

| Suspension | Control | 69.0 ± 2.9 | 24.7 ± 2.4 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.6 |

| Suspension | TRAP | 35.5 ± 2.5* | 57.9 ± 2.4* | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 0.2 |

| Adhered | Control | 64.4 ± 3.7 | 31.1 ± 2.8 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 1.2 |

| Adhered | TRAP | 62.0 ± 4.5 NS | 34.2 ± 3.5 NS | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 1.4 |

Mean ± SEM (n = 4).

Abbreviation: NS, not statistically significant compared with vehicle-treated adhered platelets.

P < .001 compared with vehicle-treated platelets in suspension.

After platelet adhesion to collagen type III, GPIb was redistributed to the platelet surface. Both TRAP-stimulated and nonstimulated adhering platelets showed pronounced cell surface ruffling (ie, pseudopod formation) (Fig 4C and D). As shown in Table 2, the percentage of GPIb on the platelet surface of vehicle-treated platelets was 64.4% ± 3.7% (mean ± SEM, n = 3). The percentage of GPIb on the platelet surface of TRAP-treated platelets was 62.0% ± 4.5% (mean ± SEM, n = 4), which was not significantly different from vehicle-treated platelets. In a parallel flow cytometric experiment, we observed that the surface expression of GPIb on TRAP-stimulated platelets present in the perfusate after perfusion was still reduced (data not shown). This means that GPIb rapidly redistribute to the platelet surface on adhered TRAP-stimulated platelets, but not on TRAP-stimulated platelets in suspension. The perfusion process by itself did not influence the time-dependent return of GPIb to the platelet surface in circulating platelets.

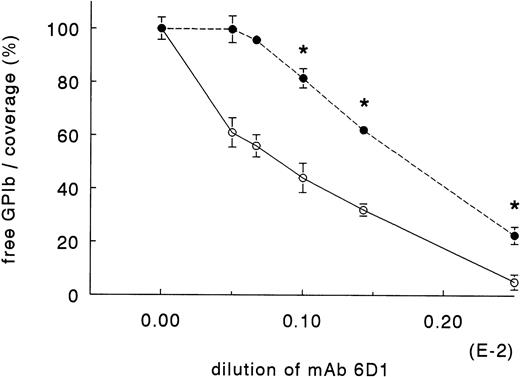

To determine the critical number of GPIb receptors on the platelet surface at which platelet adhesion becomes inhibited, we performed the following experiments. Whole blood, anticoagulated with Orgaran (15 U/mL) in the presence of dRGDW (200 μmol/L) was preincubated for 30 minutes with increasing concentrations of MoAb 6D1, which inhibits GPIb-mediated functions.23 After 30 minutes, the blood was perfused for 5 minutes at a shear rate of 1,600 s-1 over collagen type III in a single-pass perfusion system. Immediately before the start of perfusion, blood samples were drawn for flow cytometry analysis. As shown in Fig 5, a blockage of 44% of GPIb with 6D1 had no effect on platelet adhesion to collagen type III. When 56% of GPIb was occupied by 6D1, adhesion was inhibited by 18%. Adhesion decreased in a dose-dependent manner when blood was preincubated with higher concentrations of 6D1.

Effect of GPIb-receptor occupation by MoAb 6D1 on platelet adhesion to collagen type III at a shear rate of 1,600 s-1. Orgaran anticoagulated whole blood (+dRGDW) was incubated with MoAb 6D1 at room temperature for 30 minutes. The blood was then prewarmed at 37°C for 5 minutes. After prewarming, a sample was drawn for flow cytometry analysis and immediately thereafter the perfusion runs were started. The amount of free GPIb (○) was determined by flow cytometry. The platelet coverage (•) is expressed as percent control (without MoAb 6D1). Data are obtained in three independent experiments with blood from three different donors (mean ± SEM, n = 3). * Significantly different from control.

Effect of GPIb-receptor occupation by MoAb 6D1 on platelet adhesion to collagen type III at a shear rate of 1,600 s-1. Orgaran anticoagulated whole blood (+dRGDW) was incubated with MoAb 6D1 at room temperature for 30 minutes. The blood was then prewarmed at 37°C for 5 minutes. After prewarming, a sample was drawn for flow cytometry analysis and immediately thereafter the perfusion runs were started. The amount of free GPIb (○) was determined by flow cytometry. The platelet coverage (•) is expressed as percent control (without MoAb 6D1). Data are obtained in three independent experiments with blood from three different donors (mean ± SEM, n = 3). * Significantly different from control.

To determine the total amount of GPIb present on the surface, a constant concentration of FITC-conjugated MoAb 6.20 was added after platelets were fixed and washed for flow cytometry. FITC-conjugated MoAb 6.20 binds to GPIb, but has no effect on GPIb-mediated functions. The total amount of GPIb present on the platelet surface, as detected by FITC-conjugated MoAb 6.20, remained constant, independent of the binding with MoAb 6D1.

DISCUSSION

Earlier flow cytometric studies with MoAbs against GPIb-IX have shown that GPIb is downregulated on the platelet surface when platelets are stimulated in vitro by plasmin, α-thrombin, or TRAP.8,33-35 Downregulation of GPIb was also shown in vivo during CPB surgery13,14 in blood emerging from bleeding-time wounds9 and in patients with severe atherosclerosis.36 As a consequence of this decreased number of GPIb on the platelet surface and because of the central role of GPIb in platelet adhesion, the platelet adhesion to the vessel wall may be impaired.

Despite the substantial number of publications about the reduced surface expression of GPIb,8-12 33-36 it is still not known whether a decrease of GPIb on the platelet surface has any functional consequences for the adhesive capacity of platelets. For this reason, we studied platelet adhesion under flow conditions using platelets with a reduced number of GPIb on the surface. In the present study, we show that a 50% reduction of platelet surface GPIb has no effect on the GPIb-mediated platelet adhesion under flow conditions. To reduce the amount of functional GPIb on the platelet surface, two independent strategies were followed.

First, platelets were stimulated in Orgaran anticoagulated blood with 15 μmol/L TRAP. dRGDW was added to avoid platelet aggregation. The effectivity of TRAP stimulation was shown by flow cytometry, ristocetin-induced platelet agglutination, and electron microscopy. In flow cytometric studies, we showed that stimulation of platelets with TRAP decreased the amount of GPIb present on the platelet surface by approximately 65%. The TRAP-induced disappearance of GPIb was maximal approximately 5 minutes after the addition of TRAP and was followed by a time-dependent return of GPIb to the platelet surface. Immunoelectron microscopy on frozen thin sections of TRAP-stimulated platelets confirmed the decrease in GPIb on the platelet surface observed in flow cytometry. The decrease of GPIb on the platelet surface was accompanied by an increase of GPIb within the OCS and is in agreement with previous immunoelectron microscopy studies in which platelets were activated by thrombin.8,10 As previously observed with thrombin,10 37 the TRAP-induced disappearance of GPIb in our present study resulted in a decreased RIPA.

The results from our perfusion experiments clearly showed that a 65% reduction of GPIb on the platelet surface had no effect on the GPIb-mediated platelet adhesion to collagen type III and ECM under flow conditions. As previously shown by Nurden et al,38 the collagen receptor GPIaIIa does not show a reduction in surface expression on the platelet and therefore may contribute to normal adhesion.

Immunoelectron microscopy showed, however, that TRAP-stimulated platelets adhering to collagen type III had almost the same surface expression of GPIb as unstimulated platelets. These findings suggest that on adhesion GPIb rapidly returns to the platelet surface. The number of GPIb on the surface of TRAP-stimulated platelets still present in the perfusate after perfusion did not differ from that of TRAP-stimulated platelets before perfusion, suggesting that the redistribution of GPIb to the platelet surface is induced when platelets adhere. From these experiments however, it is not clear to what extent GPIb returning from the OCS to the platelet surface contributes to platelet adhesion to collagen.

To further investigate this issue, we followed a second approach and determined the critical number of GPIb receptors necessary for platelet adhesion under flow. We used a MoAb against GPIb to inhibit the function of GPIb on the platelet surface. Using this approach, we could show that inhibition of platelet adhesion only occurs when more than 50% of platelet surface GPIb is blocked.

The critical percentage of platelet surface GPIb necessary for platelet adhesion under flow varied between the different approaches followed and probably also by the different antibodies used.11Because a rapid return of GPIb to the platelet surface was observed in adhering platelets, the critical 50% reduction found by blocking the GPIb receptor is probably more realistic.

Apart from the controversial studies with respect to the clearance of GPIb from the platelet surface when platelets are stimulated with thrombin,11,39 we show here that only 50% of platelet surface GPIb is necessary for platelet adhesion under flow conditions. These results are in agreement with previous studies with carriers of the inherited disease Bernard-Soulier syndrome, who lack about 50% of GPIb, but have no bleeding complications.17 18 Our present findings further suggest that the observed disappearance of GPIb during CPB by itself, which is usually less than 50%, is unlikely to affect platelet adhesion.

In conclusion, a 50% reduction of platelet surface GPIb has no effect on platelet adhesion under flow conditions. GPIb is not only essential for platelet adhesion, but also for platelet-platelet interaction at high shear rates.40-42 At present, it is not clear why GPIb is reversibly expressed on the platelet surface. It is quite possible that the reversible surface expression of GPIb represents a refined mechanism to control thrombus formation rather than adhesion at high shear rates.

Supported by Grant No. 93.112 from The Netherlands Heart Foundation.

Address reprint requests to Jan J. Sixma, MD, University Hospital Utrecht, Department of Hematology, PO Box 85500, 3508 GA Utrecht, The Netherlands.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

![Fig. 1. Effect of different concentrations of TRAP on the platelet surface expression of GPIb and P-selectin. Orgaran anticoagulated whole blood (+ dRGDW) was incubated (5 minutes, 37°C) with various concentrations of TRAP. After 5 minutes, the blood was fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde, incubated with either MoAb 6.20 (against GPIb [▴]) or CD62 MoAb RUU-SP 2.17 (against P-selectin [•]), and analyzed by flow cytometry. Both the binding of the anti-GPIb MoAb before the addition of TRAP and the maximal binding of the anti-CD62 MoAb was assigned 100 arbitrary units of fluorescence. Data represent a typical experiment.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/91/7/10.1182_blood.v91.7.2353/3/m_blod4074001.jpeg?Expires=1766188749&Signature=CdEFyaSTjYI51RsmntMweMSkJsKayU2dYPGDeP0GSZYr2rXCpQs05WDDVP6Go3dtz3-ngA-PT0LI1n7suqWb33EUknDCFh1XORkYQH-gTaLWPbLdNHyC6AYzNm47ITK~yyoUodHYbJI8LPGrHRXwzluipfM01fQ-g63Wz9kfNZ2a5-FDnvEO4VWMAfo4GIr5vtc0pPSMO47mARXhG~Yeb9OpkbGVHH57MTSnEBwbZ2J9F~mivKr2S1lRg2hBuA75OUasdnt8WJ~7kEP4lV~MrNsB~Sh0T7JCLFPOb7UVKH~jd4QiV0g3rakQU4VvA2p7HuKra5k5M0SxIxfpBVlucA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal