Abstract

High-affinity receptors for interleukin-3 (IL-3), IL-5, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) are composed of two distinct subunits, a ligand-specific chain and a common β chain (βc). Whereas the mouse has two homologous β subunits (βc and βIL-3), in humans, only a single β chain is identified. We describe here the isolation and characterization of the gene encoding the human IL-3/IL-5/GM-CSF receptor β subunit. The gene spans about 25 kb and is divided into 14 exons, a structure very similar to that of the murine βc/βIL-3 genes. Surprisingly, we also found the remnants of a second βc chain gene directly downstream of βc. We identified a functional promoter that is active in the myeloid cell lines U937 and HL-60, but not in HeLa cells. The proximal promoter region, located from −103 to +33 bp, contains two GGAA consensus binding sites for members of the Ets family. Single mutation of those sites reduces promoter activity by 70% to 90%. The 5′ element specifically binds PU.1, whereas the 3′ element binds a yet-unidentified protein. These findings, together with the observation that cotransfection of PU.1 and other Ets family members enhances βc promoter activity in fibroblasts, reinforce the notion that GGAA elements play an important role in myeloid-specific gene regulation.

PROLIFERATION AND differentiation of hematopoietic progenitors is regulated by cytokines that are produced by a wide variety of cell types. Among these cytokines, interleukin-3 (IL-3), IL-5, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) are produced by a variety of cell types, including activated T cells and mast cells, and play an important role in hematopoiesis as well as in inflammatory reactions.1,2 Both IL-3 and GM-CSF act on various lineages of hematopoietic cells,2,3 whereas IL-5 is a more lineage-restricted cytokine that acts mainly on eosinophils, basophils, and, in the mouse, some B cells.4,5Although IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF show no amino acid homology, they have striking similarities; their genes are linked on human chromosome 5,2 they induce the phosphorylation of similar proteins,6,7 they compete with each other in binding to their high-affinity receptors in humans,8,9 and they have overlapping biological functions.2

Cloning of the receptor components and the reconstitution of functional receptors for IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF has shown that the receptors are heterodimers composed of a cytokine-specific α chain (IL3-Rα, IL-5Rα, and GM-CSFRα) and a common β chain (βc).10-12 Although the human βc subunit has no binding capacity by itself, it forms a high-affinity receptor complex by association with the low-affinity α chains. Besides its role in high-affinity binding, the βc chain plays a major role in IL-3–, IL-5–, and GM-CSF–mediated signal transduction.13,14 Therefore, the common use of the βc subunit by IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF explains the observed partial functional redundancy of these cytokines.15 However, when the entire cytoplasmic domain of the IL-5Rα is deleted, intracellular signaling is blocked, indicating that the α chain is also involved in signaling.16 17

In contrast with humans, the mouse has two β subunits, known as βc (AIC2B) and βIL-3 (AIC2A).18,19 Analogous to the human βc, the mouse βc chain is the common β subunit for the mouse IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF receptors. Although βc and βIL-3 have 91% homology at the amino acid level, only βIL-3 binds IL-3 with low affinity and does not form a high-affinity receptor with IL-5Rα and GM-CSFRα. The genes encoding βc and βIL-3 are located within 250 kb on mouse chromosome 15, and their genomic organization is almost identical. Both genes consist of 14 exons and span about 28 kb each. Furthermore, their 5′ sequences are also well-conserved.20These observations have led to the speculation that the two genes are products of a gene duplication event that occurred after the divergence of mice and humans.

Because the expression of cytokine receptors, including those for IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF, is generally restricted to hematopoietic cells, their expression has to be regulated in a cell-type–specific manner. In vitro development of murine embryonic stem (ES) cells or day-3.5 murine blastocysts, used as a model for the earliest steps of hematopoietic stem cell formation during embryogenesis,21,22 has shown that ES cells and day-3.5 blastocysts express no detectable βIL-3 or βc mRNA. However, the transcription of the two β subunits is dramatically increased after 7 to 9 days in culture, consistent with the time of blood island formation and the induction of the CD34 gene.23 Because IL-3 stimulates multipotential progenitor cells (for review, see Ogawa24), it is not surprising that CD34+ cells isolated from human bone marrow (BM) and cord blood25 and murine c-kit+ BM cells26 express the βc subunit(s). However, at later stages of development, expression of the βc chain is mainly restricted to the myeloid lineages. In the lymphoid compartment, expression is only found in a minor fraction of cells with the B-cell marker CD19, but not in cells with the T-cell marker CD3.25

Although it is clear that the expression of the βc subunit is tightly controlled, nothing is known about the molecular mechanisms underlying this regulation. Cloning and characterization of the regulating sequences of the βc gene should shed light on the cell-specific expression. Furthermore, knowledge of βc subunit expression can lead to novel leads in the treatment of IL-3/IL-5/GM-CSF signaling-related diseases, such as leukemia, and inflammatory diseases. To study βc gene expression, we have cloned and characterized the human βc locus. We show here that the genomic organization of the gene is highly homologous to the mouse AIC2A and AIC2B genes and that Ets family members, including PU.1, are involved in the regulation of its basal expression. Furthermore, our results also indicate that the human may have had a second β chain gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Library screens.

Two human genomic libraries, prepared from placental DNA in the λEMBL3 and λDASH vectors (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), were screened with the 868-bp EcoRI-Ava I (bp 2 to 869) fragment of the human βc chain cDNA11 according to standard techniques. The human chromosome 22-specific cosmid library LL22NC03 (a kind gift of Dr P.H.J. Riegman, Dept. of Pathology, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands)27 was screened with the 275-bp EcoRI-Bgl I (bp 2 to 276) fragment of the human βc chain cDNA. A genomic HincII fragment of 1,900 bp (containing exons p-2 and p-3) isolated from the cosmid library was used to screen a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) library. This screen was performed by Genome Systems, Inc (St Louis, MO). One positive clone [BACH-249 (A21)] was detected and further analyzed.

Isolation and subcloning of genomic clones.

DNA of positive phage/cosmid/BAC clones was digested with various restriction enzymes, separated on 0.4% to 0.7% agarose gels, blotted to nitrocellulose, and hybridized with various fragments of βc chain cDNA or exon-specific oligonucleotide probes. cDNA probes were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP using a random priming labeling kit (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) and hybridized for 16 hours at 42°C in standard 50% formamide buffer. Oligonucleotide probes were labeled with [γ-32P]dATP by T4 polynucleotide kinase and hybridized for 16 hours at 42°C in 6× standard sodium citrate, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulphate, 5× Denhardts’ reagent, and 0.1 mg/mL ssDNA. Positive fragments were subcloned in pBluescript II SK(−) (Stratagene).

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and DNA sequencing.

Oligonucleotide primers corresponding to the 5′ and 3′ sequences of each exon (based on the organization of the murine βc/IL-3 chain genes) were used for polymerase chain reactions to estimate the intron lengths. λDNA and BAC DNA served as templates (1 ng), using 100 ng of each primer in a reaction volume of 100 μL. For fragments ≤1,500 bp, reactions were performed for 30 cycles (1 minute at 95°C, 1.5 minutes at 46°C or 52°C, and 2 minutes at 72°C) using AmpliTaq (Perkin-Elmer, Branchburg, NJ). For fragments greater than 1,500 bp, reactions were performed for 30 cycles (1 minute at 95°C, 1.5 minutes at 46°C or 52°C, and 8 minutes at 68°C) using the Expand PCR kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). Products were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel. Fragments were subcloned using the pGEM-T cloning kit (Promega, Leiden, The Netherlands), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Supercoiled plasmid DNA was alkaline-denatured and sequenced by the dideoxy chain termination method using T7 polymerase sequencing kit (Pharmacia). Oligonucleotide primers used were from the flanking regions of the vector (T3 and T7), cDNA sequence, or from the intron sequence obtained.

RNAse protection and 5′ RACE.

RNAse protection analysis was performed according to Melton et al.28 Ten micrograms of total RNA derived from U937, HL-60, THP-1, TF-1, and HeLa cells was hybridized to 32P-labeled complementary RNA probes derived from the human βc gene. After RNase digestion of the single-strand transcripts, protected fragments were separated on a sequencing gel. A set of sequence reactions was loaded to determine the lengths of the protected fragments. HeLa and yeast tRNA served as a negative control. The 5′ RACE was performed using the Marathon cDNA amplification kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA), using 1 μg of HL-60–derived polyA+ RNA.

Cells, plasmids, oligonucleotides, and antibodies.

COS-1 and HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Life Technologies, Breda, The Netherlands) supplemented with 8% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS; Life Technologies). The monocytic cell line U937, the promyelocytic leukemia cell line HL-60, erythroleukemia TF-1 cells, and monocytic THP1 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies) supplemented with 8% FetalClone I (HyClone, Logan, UT).

The complete cDNA of PU.129 was cloned in the expression vector pSG5 (Stratagene). Expression vectors for cEts-1, GABPα/E4TF1-60, and GABPβ1/E4TF1-53 are described previously (Coffer et al30 and Watanabe et al,31respectively).

The following oligonucleotides were used in this study: for site-directed mutagenesis of the GGAA element −65, −65mut (GGGCCGGCACTGCTAGATCTTTCTGCTTCTC) and the GGAA element −45, −45mut (TTTCTGCTTCTCTGATATCTGATGACATCAAC); for band-shift analysis (only upper strand is shown), −65 (AGCTTCCGGCACTGCTTCCTCTTTCTGCTA) and −45 (AGCTTGCTTCTCTGTTTCCTGATGACATCA).

The following antibodies were used in this study: anti–Ets-1 (N-276, sc-111X; Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA), anti–Ets-2 (C-20, sc-351X; Santa Cruz), anti–Fli-1 (C-19, sc-356X; Santa Cruz), anti-PU.1 (T-21, SC-352X; Santa Cruz), anti-ATF3 (C19, sc-188X; Santa Cruz), and anti-GABPα (rabbit polyclonal, a generous gift from S.L. McKnight, Tularik, South San Francisco, CA).

Plasmids for promoter analysis, transient transfection, and CAT assay.

The BAC 2.7-kb HinDIII fragment hybridizing with an exon 1 specific oligonucleotide was subcloned into the HinDIII site of the promoterless pBLCAT3 vector32 in both orientations and sequenced. This construct was used as a template for the PCR-based deletion constructs −358/+33, −226/+33, and −103/+33. These constructs were cloned into the Xba I-BamHI sites of pBLCAT3. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed according to Kunkel.33

For transfection experiments, COS-1 cells were cultured in six-well dishes (Nunc, Naperville, IL); 3 hours later, the cells were transfected with 6 to 8 μg of supercoiled plasmid DNA, as described previously.34,35 HeLa cells were transfected 16 hours after splitting. After 16 to 20 hours of exposure to the calcium-phosphate precipitate, medium was refreshed. Cells were harvested for CAT assays 24 hours later. Transfection of U937 and HL-60 cells was performed by electroporation at 300 V and 960 μF (107 cells, 20 μg supercoiled plasmid DNA). Two days after transfection, cells were harvested for CAT assays. CAT assays were performed as described previously.36 LacZ determination was used to correct for transfection efficiency.

Gel retardation assay.

Nuclear extracts were prepared from U937, HL-60, and COS-1 cells following a previously described procedure.37Oligonucleotide probes were labeled by filling in the cohesive ends with [α-32P]dCTP using Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I. Gel retardation assays were performed as described previously.38 In supershift experiments, 2 μg of antibody was added to the extracts on ice, 45 minutes before the addition of the probe.

RESULTS

Isolation and organization of the IL-3/IL-5/GM-CSF receptor βc gene.

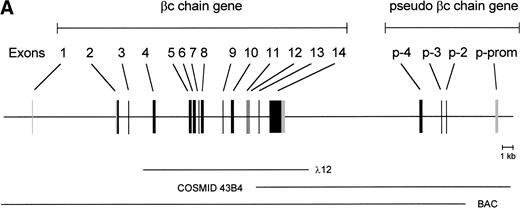

To isolate the genomic sequences of the human IL-3/IL-5/GM-CSF receptor βc gene, we initially screened a human genomic λEMBL3 library with the 868-bp EcoRI-Ava I fragment of the βc cDNA.11 The positive clone obtained (λ12) contained exons 4 to 14 (Fig 1A). To isolate exons 1 through 3 and upstream sequences, we screened the chromosome 22-specific cosmid library LL22NC03 with the 275-bpEcoRI-Bgl I probe. One positive (43B4) was shown to contain exons 2 and 3. Nevertheless, the sequences of these regions shared only about 85% and 95% homology with the cDNA, respectively (Fig 1B), highly suggesting that these exons were obtained from a pseudogene (see below).

Schematic representation of the human IL-3/IL-5/GM-CSFR β chain gene and the remains of a βc pseudogene. (A) The βc chain gene spans 25 kb and is divided into 14 exons, while of the pseudogene, only a part of the promoter and exons 2, 3, and 4 are identified (p-prom, p-2, p-3, and p-4). Coding regions are shown in black, noncoding are shown regions in gray. The phage, cosmid, and BAC clones used to characterize the locus are also indicated. (B) Alignment of the homologous regions of the βc chain gene and the pseudogene. The upper strand represents the βc chain sequence (numbers are relative to the transcription start site); the lower strand represents the pseudogene sequence (numbers are according to BAC clone F45C1). The translation start site is boxed (exon2). The p-promoter region, p-exon2, p-exon3, and p-exon4 have homology of 80%, 85%, 95%, and 89% with the βc gene, respectively.

Schematic representation of the human IL-3/IL-5/GM-CSFR β chain gene and the remains of a βc pseudogene. (A) The βc chain gene spans 25 kb and is divided into 14 exons, while of the pseudogene, only a part of the promoter and exons 2, 3, and 4 are identified (p-prom, p-2, p-3, and p-4). Coding regions are shown in black, noncoding are shown regions in gray. The phage, cosmid, and BAC clones used to characterize the locus are also indicated. (B) Alignment of the homologous regions of the βc chain gene and the pseudogene. The upper strand represents the βc chain sequence (numbers are relative to the transcription start site); the lower strand represents the pseudogene sequence (numbers are according to BAC clone F45C1). The translation start site is boxed (exon2). The p-promoter region, p-exon2, p-exon3, and p-exon4 have homology of 80%, 85%, 95%, and 89% with the βc gene, respectively.

Because exon 1 was not present in the cosmid clones, a BAC library was screened, leading to the identification of one positive clone, which appeared to contain the whole βc gene. As shown in the schematic diagram (Fig 1A), the estimated length of the gene is approximately 25 kb. The gene contains 13 introns, and all the sequences of intron-exon boundaries conform to the consensus sequences of eukaryotic splice junctions (Table 1). Because of unknown technological problems, we were not able to characterize the 3′ sequence of intron 1.

Exon/Intron Boundaries of the Human βc Chain Gene

| Exon . | Size (bp) . | Donor . | Intron (kb) . | Acceptor . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 44 | CAGAG | GTATG | -8.5- | ND | GCCTG |

| 2 | 248 | AGAAG | GTGAG | -0.9- | GTCAG | AAACC |

| 3 | 124 | AATGA | GTGAG | -2.5- | AACAG | GGACC |

| 4 | 191 | GCATG | GTGAG | -3.5- | TCCAG | TCCAG |

| 5 | 158 | GGGAG | GTAGG | -0.1- | GACAG | GACGC |

| 6 | 169 | GCCAG | GTAAT | -0.5- | CCCAG | GGGAT |

| 7 | 136 | CGAGG | GTGAG | -0.1- | CTCAG | GGAGG |

| 8 | 158 | GAACA | GTGAG | -1.9- | TCCAG | TCCAG |

| 9 | 140 | GGAAG | GTGAG | -0.9- | CACAG | GACAG |

| 10 | 163 | GTCGG | GTAGG | -1.3- | GGAAG | TGCTG |

| 11 | 91 | TACAG | GTGAG | -0.2- | TCCAG | GCTGC |

| 12 | 58 | TCCAG | GTAGG | -0.9- | TGCAG | AACGG |

| 13 | 104 | GAGGG | GTGAG | -0.7- | CACAG | GGTGT |

| 14 | 1400 | |||||

| Exon . | Size (bp) . | Donor . | Intron (kb) . | Acceptor . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 44 | CAGAG | GTATG | -8.5- | ND | GCCTG |

| 2 | 248 | AGAAG | GTGAG | -0.9- | GTCAG | AAACC |

| 3 | 124 | AATGA | GTGAG | -2.5- | AACAG | GGACC |

| 4 | 191 | GCATG | GTGAG | -3.5- | TCCAG | TCCAG |

| 5 | 158 | GGGAG | GTAGG | -0.1- | GACAG | GACGC |

| 6 | 169 | GCCAG | GTAAT | -0.5- | CCCAG | GGGAT |

| 7 | 136 | CGAGG | GTGAG | -0.1- | CTCAG | GGAGG |

| 8 | 158 | GAACA | GTGAG | -1.9- | TCCAG | TCCAG |

| 9 | 140 | GGAAG | GTGAG | -0.9- | CACAG | GACAG |

| 10 | 163 | GTCGG | GTAGG | -1.3- | GGAAG | TGCTG |

| 11 | 91 | TACAG | GTGAG | -0.2- | TCCAG | GCTGC |

| 12 | 58 | TCCAG | GTAGG | -0.9- | TGCAG | AACGG |

| 13 | 104 | GAGGG | GTGAG | -0.7- | CACAG | GGTGT |

| 14 | 1400 | |||||

Shown are the length of exons (in basepairs), length of introns (in kilobases), and the sequences of the exon-intron/intron-exon boundaries of the βc chain gene. All boundaries are in agreement with the consensus sequences of eukaryotic splice junctions. Because of unknown technological problems, we were not able to characterize the 3′ sequence of intron 1.

The length of the gene and the number of exons are not the only striking similarities between the human βc and murine βc/βIL-3 genes. Exon 1 encodes 5′-untranslated sequences, and exon 2 encodes more 5′-untranslated sequences and the start of the open reading frame. The extracellular domain is encoded by 9 exons (exon 2 to 10), the transmembrane domains are on the 11th exon and cytoplasmic domain by three exons (exon 12 through 14). Exon 14 also contains the 3′ untranslated sequences. Also, the relative lengths of the introns are very comparable between mice and humans.

The remains of a second βc gene?

Interestingly, the mutated exons 2 and 3 identified in cosmid 43B4 were also found in the BAC. Furthermore, in both the BAC and cosmid clones, a region homologous to exon 4 was also found (89% homology; Fig 1B). Interestingly, a BLAST search identified a cosmid clone F45C1 (GenBank accession no. Z75892) that is (at least partially) identical to our cosmid clone 43B4. The complete sequence of cosmid F45C1 is available in the GenBank and confirmed the genomic organization of the exons 11 to 14 and the localization of a pseudo β chain gene, as depicted in Fig 1A.

The 5′ flanking region.

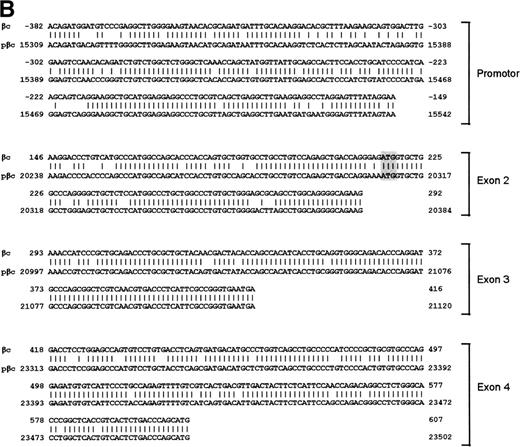

To identify the functional promoter of the βc chain gene, a 2.7-kbHinDIII fragment hybridizing with an exon 1-specific oligonucleotide was cloned and completely sequenced (GenBank accession no. AF069543). Computer analysis showed a TATA-box (TFIID/TBP binding site) and a cap sequence that were also found in the murine sequence. To localize the transcription start site(s), we performed an RNase protection assay with total RNA from HL-60, U937, TF-1, THP-1, and HeLa (negative control) cells and used a genomic sequence that contained exon1 as a probe. Figure 2A shows that fragments of 44, 45, 50, and 58 bp are protected in βc subunit-expressing cells but not in HeLa cells. The integrity of these start sites was confirmed by 5′ RACE analysis using polyA+ RNA from HL-60 cells (data not shown). These results indicate that multiple initiation sites are used at 11, 19, 24, and 25 bp from the putative TATA box (Fig 2B). Alignment of the human and murine sequences (Fig 2B) showed the high degree of homology of the promoter proximal regions, including the first exon. We therefore placed the +1 at the same position as the major transcription start site found in the murine genes, corresponding to the 44-bp protected fragment.

RNase protection and sequence alignment of the proximal promoter region of the human and mouse βc chain genes. (A) RNase protection was used to determine transcription start sites. Specific protected fragments of 44, 45, 50, and 58 nucleotides were observed in βc expressing HL-60, butyric acid (BA)-treated HL-60, U937, TF-1, and THP-1 cell lines, but not in the HeLa and tRNA control lanes. The integrity of these start sites was confirmed by 5′ RACE analysis on HL-60–derived polyA+ RNA. (B) The putative TFIID/TBP binding sites are indicated in boldface and underlined, the first exons are indicated in bold face, and transcription start sites, identified by RNase protection and 5′ RACE, are indicated by asterisks. Several putative binding sites for different transcription factor families, including cEts, cMyb, MZF-1, GATA-1, STAT, cMyc, and C/EBP are identified in the human sequence. Ets-binding sites studied in this report are named −65 and −45 and are indicated in boldface. Furthermore, these elements are conserved in the murine sequence.

RNase protection and sequence alignment of the proximal promoter region of the human and mouse βc chain genes. (A) RNase protection was used to determine transcription start sites. Specific protected fragments of 44, 45, 50, and 58 nucleotides were observed in βc expressing HL-60, butyric acid (BA)-treated HL-60, U937, TF-1, and THP-1 cell lines, but not in the HeLa and tRNA control lanes. The integrity of these start sites was confirmed by 5′ RACE analysis on HL-60–derived polyA+ RNA. (B) The putative TFIID/TBP binding sites are indicated in boldface and underlined, the first exons are indicated in bold face, and transcription start sites, identified by RNase protection and 5′ RACE, are indicated by asterisks. Several putative binding sites for different transcription factor families, including cEts, cMyb, MZF-1, GATA-1, STAT, cMyc, and C/EBP are identified in the human sequence. Ets-binding sites studied in this report are named −65 and −45 and are indicated in boldface. Furthermore, these elements are conserved in the murine sequence.

Searching the TFMATRIX transcription factor database (http://pdap1.trc.rwcp.or.jp/research/db/TFSEARCH.html), putative binding sites were identified throughout the 2.7-kb fragment. In the proximal promoter region from −495 to +54 relative to the transcription start site, these include binding sites for the transcription factor families of cEts, STAT, cMyc, Myb, GATA, and C/EBP (Fig 2B).

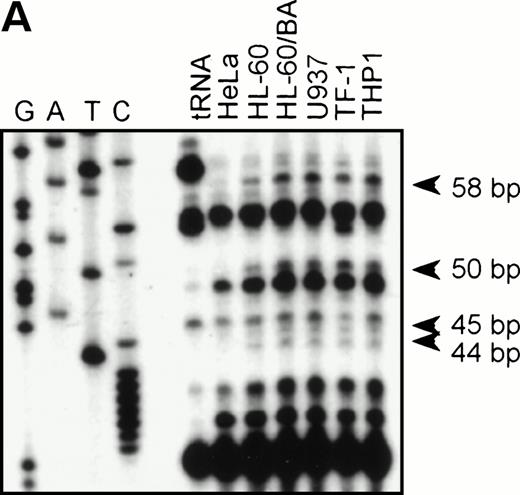

The functionally active promoter region is cell-type specific.

To study whether the sequences upstream of exon 1 had promoter activity, the 2.7-kb HinDIII fragment was cloned into the promoterless CAT-vector pBLCAT3 in both forward (F) and reverse (R) orientation. The plasmids, −2100/+600CAT-F and −2100/+600CAT-R, were transfected into the monocytic cell line U937, the promyelocytic leukemia cell line HL-60, and the cell lines COS-1 and HeLa. CAT activity was measured 2 days after transfection. As shown in Fig 3, CAT activity was clearly detected in U937, HL-60, and COS-1 cells transfected with −2100/+600CAT-F (F), but not in HeLa cells or cells transfected with −2100/+600CAT-R (R). As a negative control, we used the empty pBLCAT3 vector (V). As a positive control for HeLa cell transfection, we used CAT plasmids with the RSV promoter. The results indicate that the 2.7-kb HinDIII fragment contains a functional promoter with some degree of cell-type–specific activity.

The βc chain promoter has cell-type–specific activity. The 2.7-kb HinDIII fragment was cloned into pBLCAT3 in both forward (F) and reverse (R) orientation and subsequently transfected into U937, HL-60, COS-1, and HeLa cells. Empty vector (V) was used as a negative control; a CAT reporter plasmid driven by an RSV promoter was used as a positive control (RSV). Promoter activity can only be detected in U937, HL-60, and COS-1 cells transfected with the forward construct, indicating that the 2.7-kb HinDIII fragment contains a functional promoter. Values are the mean of at least four independent experiments; the error bars indicate the standard deviation. LacZ determination was used to correct for transfection efficiency.

The βc chain promoter has cell-type–specific activity. The 2.7-kb HinDIII fragment was cloned into pBLCAT3 in both forward (F) and reverse (R) orientation and subsequently transfected into U937, HL-60, COS-1, and HeLa cells. Empty vector (V) was used as a negative control; a CAT reporter plasmid driven by an RSV promoter was used as a positive control (RSV). Promoter activity can only be detected in U937, HL-60, and COS-1 cells transfected with the forward construct, indicating that the 2.7-kb HinDIII fragment contains a functional promoter. Values are the mean of at least four independent experiments; the error bars indicate the standard deviation. LacZ determination was used to correct for transfection efficiency.

GGAA elements are essential for promoter activity.

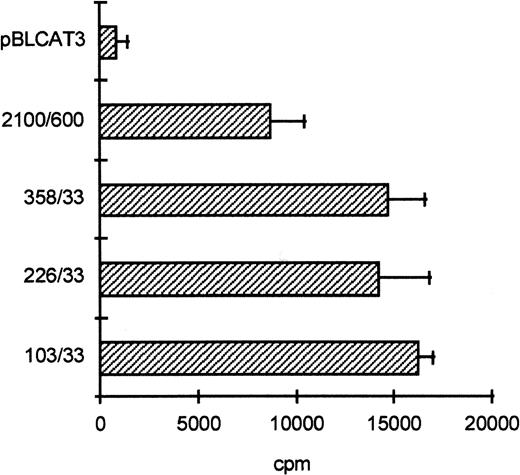

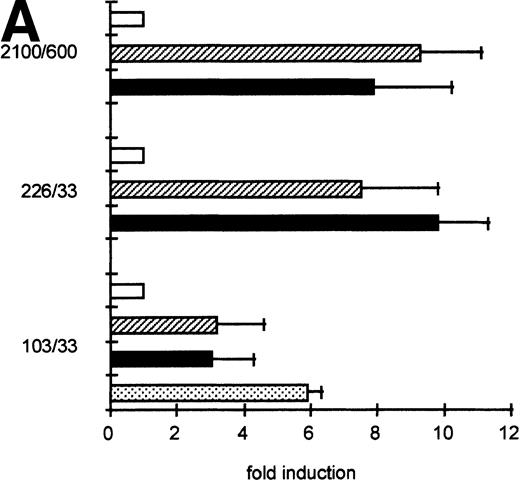

To determine the functionally important regions of the βc chain promoter, PCR-based deletion mutants were constructed. As shown in Fig 4, the deletion constructs −358/+33CAT, −226/+33CAT, and −103/+33CAT, which also lack the intron sequences, still had high promoter activity in HL-60 and U937 cells (endpoints of these constructs are indicated in Fig 2B). This indicates that an important cis-acting element(s) is located within the first 103 bp upstream of the transcription start site. Further examination of the promoter sequence showed that at least five putative cEts/PU.1 binding sites could be identified in the human proximal promoter region (Fig 2B). To test whether these sites could play a role in promoter regulation, the constructs −226/+33CAT, −103/+33CAT, and also −2100/+600 were cotransfected with the cDNAs of several Ets family members into COS-1 cells. As shown in Fig 5A, cotransfection of cEts-1 or PU.1 led to an 8 to 10 times increase of promoter activity of the constructs −2100/+600 and −226/+33CAT. Also, the activity of −103/+33CAT was induced by cEts-1 and PU.1, although only threefold. This was due to the high background level of this construct in COS-1 cells (data not shown). Overexpression of the related Ets family member GABP also resulted in increased promoter activity of −103/+33CAT (Fig 5A).

The proximal promoter contains important regulating sequences. Promoter constructs −2100/+600, −358/+33, −226/+33, and −103/+33 were transfected into HL-60 cells. Empty vector pBLCAT3 was used as a negative control. All constructs have high promoter activity, indicating that positively regulating elements are located within the first 103 bp of the proximal promoter. Values are the mean of at least four independent experiments; the error bars indicate the standard deviation. LacZ determination was used to correct for transfection efficiency. No difference was observed between HL-60 and U937 cells (not shown).

The proximal promoter contains important regulating sequences. Promoter constructs −2100/+600, −358/+33, −226/+33, and −103/+33 were transfected into HL-60 cells. Empty vector pBLCAT3 was used as a negative control. All constructs have high promoter activity, indicating that positively regulating elements are located within the first 103 bp of the proximal promoter. Values are the mean of at least four independent experiments; the error bars indicate the standard deviation. LacZ determination was used to correct for transfection efficiency. No difference was observed between HL-60 and U937 cells (not shown).

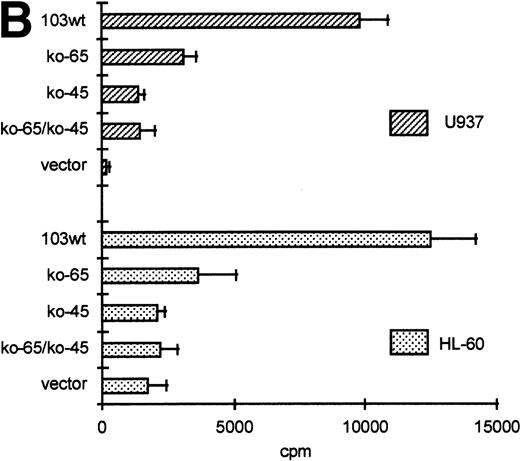

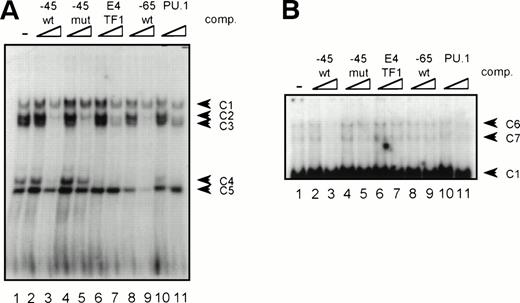

GGAA binding proteins regulate βc chain promoter activity. (A) Cotransfection of Ets family members cEts-1, PU.1, and GABP enhances promoter activity in fibroblasts. COS-1 cells were transfected with 2 μg of promoter and 6 μg of Ets expression vector or pSG5 (negative control). Promoter activity of the constructs −2100/+600 and −226/+33 is enhanced 8 to 10 times, whereas construct −103/+33 is activated only 3 times, probably due to the high basal activity of −103/+33 in COS cells. (□) pSG5; (▨) cEts; (▪) PU.1; (▧) GABP+β. (B) Ets-binding sites −65 and −45 are crucial for promoter activity. Both binding sites were mutated in the −103/+33 construct and tested for promoter activity. Both single mutations and the double mutation show a clear decrease in promoter function in both U937 and HL-60 cells. Values are the mean of at least four independent experiments; the error bars indicate the standard deviation. LacZ determination was used to correct for transfection efficiency. (C) Point mutations in Ets-binding sites −65 and −45 prevent binding of several protein complexes. The −103/+33 fragments were used in a band shift assay, using 10 μg of nuclear extract HL-60 cells. When site −65 is mutated, complexes C2 and C3 are no longer observed (lanes 2 and 4), whereas binding of C1 is also decreased. Mutation of site −45 prevents complex C4 from binding (lanes 3 and 4). Similar results were obtained when using U937 cells (data not shown).

GGAA binding proteins regulate βc chain promoter activity. (A) Cotransfection of Ets family members cEts-1, PU.1, and GABP enhances promoter activity in fibroblasts. COS-1 cells were transfected with 2 μg of promoter and 6 μg of Ets expression vector or pSG5 (negative control). Promoter activity of the constructs −2100/+600 and −226/+33 is enhanced 8 to 10 times, whereas construct −103/+33 is activated only 3 times, probably due to the high basal activity of −103/+33 in COS cells. (□) pSG5; (▨) cEts; (▪) PU.1; (▧) GABP+β. (B) Ets-binding sites −65 and −45 are crucial for promoter activity. Both binding sites were mutated in the −103/+33 construct and tested for promoter activity. Both single mutations and the double mutation show a clear decrease in promoter function in both U937 and HL-60 cells. Values are the mean of at least four independent experiments; the error bars indicate the standard deviation. LacZ determination was used to correct for transfection efficiency. (C) Point mutations in Ets-binding sites −65 and −45 prevent binding of several protein complexes. The −103/+33 fragments were used in a band shift assay, using 10 μg of nuclear extract HL-60 cells. When site −65 is mutated, complexes C2 and C3 are no longer observed (lanes 2 and 4), whereas binding of C1 is also decreased. Mutation of site −45 prevents complex C4 from binding (lanes 3 and 4). Similar results were obtained when using U937 cells (data not shown).

The fragment −103/+33 contains two GGAA elements, one at bp −44 to −47 (named −45) and the other at bp −65 to −68 (named −65). These two elements are also present in the murine promoter sequence,20 whereas the three additional elements in construct −495/+54 are not conserved in the mouse promoter. To elucidate whether the cEts/PU.1 binding elements are functionally important, both cEts/PU.1 sites were mutated in the −103/+33CAT construct. Single mutation of the −65 site resulted in a decrease of promoter activity of more than 70% in both U937 and HL-60 cells (Fig 5B). When only the −45 site is mutated, promoter activity is decreased by 90% to 95%. When both sites were mutated, no additional effects could be measured. These data show that both elements are essential for promoter activity and suggest the cooperation of the proteins binding to the elements. It should be noted that some residual activity of the double mutant could be detected in U937 cells, in contrast to HL-60 cells.

To study whether the mutations at −65 and −45 indeed resulted in a change in proteins binding to the βc promoter, we performed band shift analysis using the −103/+33 bp fragments as probe (Fig 5C). As was expected, the mutations prevented binding of different protein complexes (complexes C2 and C3 for mutation −65, while also binding of C1 is moderately affected; complex C4 for mutation −45). Moreover, they did not artificially form a site for another specific binding activity. These results show that two different GGAA elements play a major role in the regulation of the βc chain gene promoter. Interestingly, these results also suggest that both elements independently bind different proteins, because the complex binding to −45 has a lower mobility than the complexes binding to −65.

PU.1 and another GGAA-binding protein bind to the βc promoter.

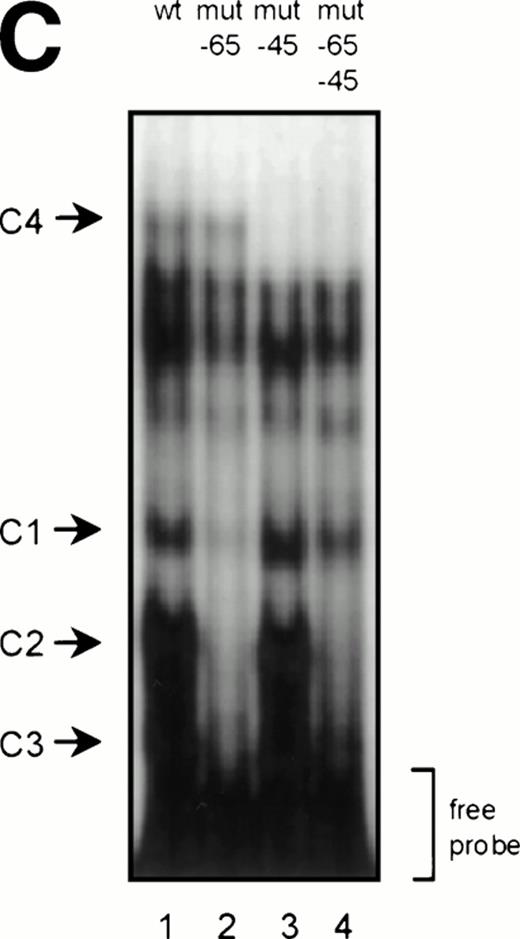

Because the proteins binding to several GGAA-elements in other myeloid-specific promoters are well characterized, sequences of those elements were aligned with −65 and −45. As shown in Table 2, the sequences flanking the well-conserved GGAA core are highly diverse. It is therefore not possible to predict which Ets protein binds to a certain GGAA element. Therefore, band shift analysis was used to further study the proteins binding to the elements −65 and −45. As shown in Fig 6A, element −65 was indeed able to bind several protein complexes (lane 1). Binding of the observed complexes was specific, because binding could be competed with a 10 to 100 molar excess of cold self oligo, but not with mutant oligo (lanes 2 and 3 and lanes 4 and 5, respectively). Binding could also be competed with an element from the G-CSFR promoter that specifically binds PU.1 (lanes 6 and 7, see also Table 2, G-CSFR 5′), an oligo that binds E4TF1/GABPα (lanes 8 and 9, see also Table 2), but not with element −45, again indicating that −65 and −45 bind different proteins. These results further show that PU.1 and GABP are possible candidates to bind to −65. To further identify the protein binding to −65, extracts were preincubated with specific antibodies against Ets family members that are implicated in hematopoietic gene regulation, including Ets-1, Ets-2, Fli-1, PU.1, and GABPα.39 Anti-ATF3 was used as a negative control. Figure 6B shows that all complexes are shifted after the addition of anti-PU.1, clearly demonstrating that PU.1 is binding to −65. Also, the addition of anti-GABPα results in a weak supershifted complex (indicated by an arrow), but this complex was also observed in the absence of nuclear extract (data not shown). Band shift assays were also performed with nuclear extracts of COS cells transfected with PU.1 and GABPα cDNA. Overexpressed PU.1 strongly binds to −65 and comigrates with the most prominent complex observed in HL-60 and U937 cells, whereas GABPα did not bind to −65 (data not shown). All together, these results show that the complexes binding to −65 contain PU.1. The less prominent and faster migrating complexes might represent different phosphorylation states of PU.1, as were previously observed.40

Alignment of GGAA Sites in Known Regulatory Regions of Human Genes

| Promoter . | Target Sequence . | In Vitro Binding . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|

| −65 (βc 5′) | AAGA GGAA GCA | ||

| −45 (βc 3′) | ATCA GGAA ACA | ||

| GM-CSFRα | ATGA GGAA GCA | PU.1 | 50 |

| G-CSFR 5′ | TTCA GGAA CTT | PU.1 | 49 |

| G-CSFR 3′ | TCAA GAGA AGT | PU.1 | 49 |

| M-CSFR | AAGG GGAA GAA | PU.1 | 48 |

| Myeloperoxidase 5′ | GTAG GGAA AAG | PU.1 | 52 |

| Myeloperoxidase 3′ | AAGG GGAA GCA | PU.1 | 52 |

| EDN 5′ | GACA GGAA GTA | PU.1 | 38 |

| EDN 3′ | TAAA GGAA ATG | PU.1 | 38 |

| E4TF1 | AAAC GGAA GTG | GABP | 31 |

| Neutrophil elastase | GGGA GGAA GTA | GABP | 55 |

| cMyc 3′ | GACC GGAA GTG | Fli-1 | 58 |

| Polyoma virus enhancer | AGCA GGAA GTG | Fli-1 | 58 |

| Consensus | DNVV GGAA VND |

| Promoter . | Target Sequence . | In Vitro Binding . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|

| −65 (βc 5′) | AAGA GGAA GCA | ||

| −45 (βc 3′) | ATCA GGAA ACA | ||

| GM-CSFRα | ATGA GGAA GCA | PU.1 | 50 |

| G-CSFR 5′ | TTCA GGAA CTT | PU.1 | 49 |

| G-CSFR 3′ | TCAA GAGA AGT | PU.1 | 49 |

| M-CSFR | AAGG GGAA GAA | PU.1 | 48 |

| Myeloperoxidase 5′ | GTAG GGAA AAG | PU.1 | 52 |

| Myeloperoxidase 3′ | AAGG GGAA GCA | PU.1 | 52 |

| EDN 5′ | GACA GGAA GTA | PU.1 | 38 |

| EDN 3′ | TAAA GGAA ATG | PU.1 | 38 |

| E4TF1 | AAAC GGAA GTG | GABP | 31 |

| Neutrophil elastase | GGGA GGAA GTA | GABP | 55 |

| cMyc 3′ | GACC GGAA GTG | Fli-1 | 58 |

| Polyoma virus enhancer | AGCA GGAA GTG | Fli-1 | 58 |

| Consensus | DNVV GGAA VND |

Elements −65 and −45 are aligned with Ets-binding sites of hematopoietic specific genes (except cMyc and polyoma virus enhancer). Because the sequences flanking the well-conserved GGAA core are highly diverse, no real consensus binding site for a particular Ets family member is present. Elements −65 and −45 have highest homology with the PU.1-binding GGAA site of the GM-CSFα promoter.

GGAA element −65 specifically binds PU.1. (A) An oligonucleotide encompassing the Ets-binding site −65 was used in a band shift assay with nuclear extracts of HL-60 cells. One prominent and several minor complexes are observed (lane 1). All complexes can be competed with a 10- to 100-fold molar excess of cold self oligo (lanes 2 and 3), but not with mutant oligo (lanes 4 and 5), indicating that the complexes bind specifically. Binding is also inhibited by addition of the PU.1 binding element of the G-CSFR and by E4TF1, a sequence that binds GABP, but not by element −45 (lanes 6 through 11). (B) To identify the protein(s) binding to −65, 2 μg of specific antibody against different Ets family members was added before the addition of the probe. Anti-ATF3 was used as a negative control. Complexes are only supershifted when anti-PU.1 is added (lane 5). The arrow indicates a nonspecific complex that appears after addition of anti-GABP (lane 6). However, this complex is also observed when no nuclear extract is added (data not shown). These results show that PU.1 binds to element −65. Similar results were obtained when using U937 cells (data not shown).

GGAA element −65 specifically binds PU.1. (A) An oligonucleotide encompassing the Ets-binding site −65 was used in a band shift assay with nuclear extracts of HL-60 cells. One prominent and several minor complexes are observed (lane 1). All complexes can be competed with a 10- to 100-fold molar excess of cold self oligo (lanes 2 and 3), but not with mutant oligo (lanes 4 and 5), indicating that the complexes bind specifically. Binding is also inhibited by addition of the PU.1 binding element of the G-CSFR and by E4TF1, a sequence that binds GABP, but not by element −45 (lanes 6 through 11). (B) To identify the protein(s) binding to −65, 2 μg of specific antibody against different Ets family members was added before the addition of the probe. Anti-ATF3 was used as a negative control. Complexes are only supershifted when anti-PU.1 is added (lane 5). The arrow indicates a nonspecific complex that appears after addition of anti-GABP (lane 6). However, this complex is also observed when no nuclear extract is added (data not shown). These results show that PU.1 binds to element −65. Similar results were obtained when using U937 cells (data not shown).

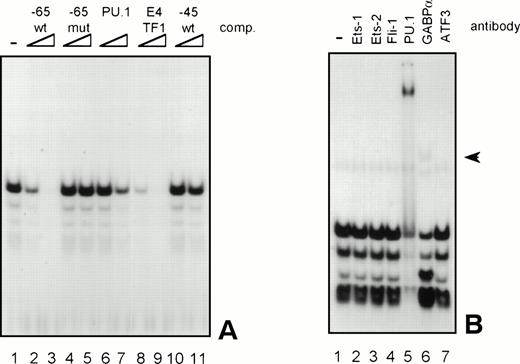

The same procedure was followed to characterize the proteins binding to element −45. In extracts of HL-60 and U937 cells, binding of a number of complexes was observed (Fig 7A, lane 1), of which complexes C2, C3, and C4 could be competed by addition of cold self oligo (lanes 2 and 3). However, binding of C2 and C3 could also be inhibited by mutant −45 oligo, as well as by the E4TF1, −65, and PU.1 oligonucleotides (lanes 4 through 11), suggesting that C2 and C3 are nonspecific complexes. Complexes C1 and C5 are also nonspecific, because the addition of cold self oligo did not affect binding of these complexes. Supershift analysis showed that C4 is a complex containing PU.1, explaining why binding of this complex could be inhibited by addition of excess self-, E4TF1-, PU.1-, and −65 oligo, but not by mutant −45 oligo. Nevertheless, previous experiments, together with the observation that overexpressed PU.1 only weakly binds to −45, have indicated that PU.1 is likely not the most prominent protein that binds to this element. Interestingly, longer exposure of the same gel led to the identification of two complexes (C6 and C7, Fig 7B), running with lower mobility than C1 in Fig 7A, that only could be competed with cold self oligo (lanes 2 and 3 and 4 through 11). Repetitive experiments showed that these complexes were present in U937 and HL-60 cells and that binding was highly sensitive to freeze-thawing (data not shown). Furthermore, the complexes could not be supershifted with antibodies against Ets-1, Ets-2, Fli-1, PU.1, and GABPα (data not shown) These results show that a yet-unidentified protein and, to a lesser extent, PU.1 bind to the 3′ GGAA-element in the promoter proximal region.

GGAA-element −45 binds an unidentified protein. (A) An oligonucleotide encompassing the Ets-binding site −45 was used in a band shift assay with nuclear extracts of HL-60 cells. Five complexes (C1 through C5) bound to −45 (lane 1), of which C2, C3, and C4 could be competed with excess of self oligo (lanes 2 and 3). Complexes C1 and C5 were nonspecific, because these complexes could not be competed. Moreover, C2 and C3 were also nonspecific, because they could be competed with mutant oligo (lanes 4 and 5). With supershift analysis it was shown that C4 contains PU.1 (not shown), explaining why binding of C4 was blocked by the addition of −45, E4TF1, −65, and PU.1 oligonucleotides. Similar results were obtained when using U937 cells (data not shown). (B) Longer exposure of the gel shown in (A). Binding of two complexes with low mobility (C6 and C7) was detected. Binding of these complexes could be inhibited with excess of self oligo only, showing the binding specificity of these complexes. These complexes could not be supershifted with antibodies against Ets-1, Ets-2, Fli-1, PU.1, and GABP. Similar results were obtained when using U937 cells (data not shown).

GGAA-element −45 binds an unidentified protein. (A) An oligonucleotide encompassing the Ets-binding site −45 was used in a band shift assay with nuclear extracts of HL-60 cells. Five complexes (C1 through C5) bound to −45 (lane 1), of which C2, C3, and C4 could be competed with excess of self oligo (lanes 2 and 3). Complexes C1 and C5 were nonspecific, because these complexes could not be competed. Moreover, C2 and C3 were also nonspecific, because they could be competed with mutant oligo (lanes 4 and 5). With supershift analysis it was shown that C4 contains PU.1 (not shown), explaining why binding of C4 was blocked by the addition of −45, E4TF1, −65, and PU.1 oligonucleotides. Similar results were obtained when using U937 cells (data not shown). (B) Longer exposure of the gel shown in (A). Binding of two complexes with low mobility (C6 and C7) was detected. Binding of these complexes could be inhibited with excess of self oligo only, showing the binding specificity of these complexes. These complexes could not be supershifted with antibodies against Ets-1, Ets-2, Fli-1, PU.1, and GABP. Similar results were obtained when using U937 cells (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Early hematopoietic CD34+ cells stem cells express the βc subunit,25 which is the main signaling component of the IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF receptors. However, at later stages of differentiation, expression of the βc chain is mainly restricted to the myeloid lineages. Uncovering the molecular mechanisms that drive its expression will contribute to the understanding of the events of myeloid commitment and differentiation. Because nothing is known about its organization, we have cloned and characterized the human βc gene and its regulating sequences.

In our initial genomic library screen, only a single clone, containing region from exon 4 to exon 14, was isolated. Screening of several genomic phage libraries, a chromosome 22-specific cosmid library, and a P1 genomic library did not lead to the cloning of more upstream sequences. This shows that the region containing the βc gene, 22q12.2 to 22q13.1,41 does not efficiently integrate in a cloning vector. Interestingly, Collins et al42 were not able to clone the regions 22q11 and 22q13 into YACs, probably due to extensive low-copy repeats and the high G+C content, respectively.43 44

A unique feature of the evolution of the β subunits of the IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF receptors is that, in the human system, only one β chain is expressed that is shared by the three receptors.10-12 In contrast, in the mouse, two distinct but homologous β subunits are identified: one (AIC2A) specific for IL-319 and the other (AIC2B) equivalent to the human βc chain.18 The absence of a second human β chain as well as the high degree of sequence homology and the close linkage between the AIC2A and AIC2B genes has led to the hypothesis that the AIC2A gene has arisen from a gene duplication that occurred after divergence between mice and humans.20 Unraveling of the genomic structure of the human βc gene indeed showed a high degree of homology with the murine βc and βIL-3 genes. The structural organization, length, and number of exons are identical, while also the total length of the genes, the sequences of the intron-exon junctions, the length of the introns, and the promoter proximal region, including TATA-box and transcription start site, are closely related. RNase protection and 5′ RACE showed the existence of several transcription start sites, all close to the putative TATA box. Whether the TATA box is functional or the basal transcription machinery is recruited by Ets factors binding to adjacent elements remains unclear at this point. Interestingly, 3′ of the βc gene we also found a region containing sequences highly homologous to the 5′ upstream region and exons 2, 3, and 4 of the βc gene. This strongly suggests that a gene-duplication occurred before the divergence of human and mouse. In the mouse, these two genes evolved to βc and βIL-3, whereas in the human, chromosomal mutations and reorganizations destroyed one of the two genes. On the other hand, it cannot be ruled out that the pseudo gene is the result of a human-specific duplication event, in which only the first few exons are duplicated.

When linked to a promoterless CAT gene, the 2.7-kb HinDIII fragment (−2100/+600CAT) directed transcription in human myeloid U937 and HL-60 cells and in monkey COS-1 fibroblasts, but not in human cervical carcinoma cells (HeLa). These results indicate that the 2.7-kbHinDIII fragment contains the promoter that functions in a cell-specific, but not hematopoietic-specific manner. Putative binding sites for hematopoietic specific transcription factors (TFs), including those for GATA, C/EBP, Myb, and MZF, as well as those for more general expressed TFs such as cEts, Sp1, and AP-1, can be found throughout the −2100/+600 sequence. Also, recognition sequences for the inducible TFs, such as STAT and NFκB, are detected. These sites could be of interest, because interferon-γ (IFN-γ), erythropoietin (EPO), stem cell factor (SCF), IL-3, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) have been described to enhance βc expression.25 45-47 Further studies are necessary to address whether one of the STAT and/or NFκB sites are functional. On the other hand, important regulating sequences have to be present in the proximal promoter region, because deletion constructs −358/+33CAT, −226/+33CAT, and −103/+33CAT exhibit maximal promoter activity. Within the proximal promoter sequence, several putative cEts binding sites can be identified.

PU.1 (Spi-1) is a member of the Ets transcription factor family and its expression is restricted to hematopoietic cells.29 PU.1 has been implicated in the regulation of different myeloid-specific genes, including macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor (M-CSFR),48 granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor (G-CSFR),49 GM-CSFRα,50neutrophil elastase,51 myeloperoxidase,52 and eosinophil-derived neurotoxin (EDN).38 Other Ets factors, including the more widely expressed GABP/E4TF1,38,53 were also shown to be involved in the regulation of several hematopoietic genes.54-56 GABP binds to the GGAA sequence and can both compete and cooperate with PU.1.54 Cotransfection of PU.1, GABP, and also cEts-1 strongly enhance the activity of the full-length promoter as well as the shorter promoter constructs in COS-1 cells. This shows that GGAA binding transcription factors can play a role in βc chain expression. Because GABP is constitutively expressed in COS-1 cells, activity of this factor might be a good explanation for the promoter activation when transfected in COS-1 cells.

In the smallest promoter fragment exhibiting maximal promoter activity (−103/+33CAT), two GGAA elements were identified, one at position −65 (GAGGAAGCAG) and the other at −45 (CAGGAAACAG). Our data show that both elements are functional, because single mutations of the −65 site and −45 site result in a 70% to 80% and 85% to 95% loss of promoter activity, respectively. The double mutant has no additional effect, suggesting the cooperation of the factors binding to elements −45 and −65. It is unclear why some residual activity of the double mutant could be measured in U937 cells, whereas not in HL-60 cells. Fragment −103/+33 is still able to bind some proteins when both sites are mutated (Fig 5C). It is possible that there is a difference in activity between these proteins in U937 and HL-60 cells that cannot be detected in a band shift assay, giving rise to the observed different residual activity.

Although both elements differ only in a few bases, gel shift analysis shows that both elements bind different protein complexes. With competition experiments and supershift analysis it was shown that PU.1 specifically binds to element −65, whereas another, unidentified protein binds to −45. Binding of PU.1 to the −65 element was confirmed by DNA affinity precipitation from U937 and HL-60 nuclear extracts (data not shown). Although PU.1 binding to −45 was also observed, different experiments have indicated that PU.1 is not the major or not the only protein binding to this element: (1) mutation of the −65 site in the −103/+33 construct almost completely reduces the binding of PU.1-containing complexes (Fig 5C, lane 2, complexes C2 and C3); (2) mutation of element −45 in the same experiment does not affect binding of these complexes, whereas complex C4 is no longer present (lane 3); (3) binding of PU.1 to −65 cannot be competed with a 100 molar excess of cold −45 oligo (Fig6A, lane 11); and (4) overexpressed PU.1 only weakly binds to −45 in a band shift assay (data not shown). Moreover, we found that two slowly migrating complexes specifically bound to the −45 element. Antisera against Ets-1, Ets-2, Fli-1, PU.1, and GABPα did not recognize these complexes. Further experiments are necessary to identify these proteins and to elucidate their role in βc gene regulation.

IL-3, GM-CSF, G-CSF, and M-CSF play crucial roles in the proliferation of early hematopoietic progenitor cells and the subsequent differentiation towards different myeloid lineages. Therefore, our finding that the expression of the IL-3/IL-5/GM-CSF receptor βc is controlled by PU.1, as was previously also shown for the M-CSFR, the G-CSFR, and the GM-CSFRα, correlates well with the observation that mice lacking PU.1 have no macrophages, granulocytes, and B and T lymphocytes.57 In conclusion, this study reinforces the notion that GGAA elements play an important role in myeloid-specific gene regulation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Prof S.L. McKnight for the gift of antisera against GABPα and GABPβ.

Supported by a research grant from GlaxoWellcome b.v.

The sequence of the IL-3/IL-5/GM-CSFR βc promoter has been deposited in the GenBank data base (accession no. AF069543).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Rolf P. de Groot, PhD, Department of Pulmonary Diseases, G03.550, University Hospital Utrecht, Heidelberglaan 100, 3584 CX Utrecht, The Netherlands; e-mail: R.deGroot@hli.azu.nl.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal