Abstract

Dendritic cells (DC) take up antigen from the periphery and migrate to the lymphoid organs where they present the processed antigens to T cells. The propensity of DC to migrate changes during DC maturation and is probably dependent on alterations in the expression of chemokine receptors on the surface of DC. Secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine (SLC), a recently discovered chemokine for naı̈ve T cells, is primarily expressed in secondary lymphoid organs and may be important for colocalizing T cells with other cell types important for T-cell activation. We show here that SLC is a potent chemokine for mature DC but does not act on immature DC. SLC also induced calcium mobilization specifically in mature DC. SLC and Epstein-Barr virus–induced molecule 1 ligand chemokine completely cross-desensitized the calcium response of each other, indicating that they share similar signaling pathways in DC. The finding that SLC is a potent chemokine for DC as well as naı̈ve T cells suggests that it plays a role in colocalizing these two cell types leading to cognate T-cell activation.

DENDRITIC CELLS (DC) are dedicated antigen-presenting cells that stimulate T-cell–dependent immune responses.1,2 This process involves the capture and processing of antigens by DC in the periphery, their migration to regional lymph nodes via the lymphatics, and the presentation of the processed antigens to T cells. Bacterial products such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and inflammatory signals such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 (IL-1) have been shown to induce the maturation of DC, which is characterized by an increased surface expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and class II, upregulation of T-cell costimulatory molecules such as CD80, CD86 and CD40, as well as enhanced ability to stimulate T cells.1 Chemokines such as C5a, fMLP, SDF-1, MCP-3, MCP-4, RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, MIP-5, and MDC have been reported to induce the migration of immature DC in vitro.3-7 Recently, three groups reported that mature/activated DC downregulate their responses to inflammatory cytokines such as MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES, and fMLP while they upregulate their response to Epstein-Barr virus–induced molecule 1 ligand chemokine (ELC).8-10 These results suggest a mechanism by which DC relocate from the site of inflammation to the lymph node where they initiate immune responses.

SLC/6Ckine/exodus-2/TCA4 is a recently identified CC chemokine.11-14 This chemokine has been reported to be chemotactic to lymphocytes but not monocytes or neutrophils. SLC is primarily expressed in secondary lymphoid tissues such as the lymph nodes, Peyer’s patches, spleen, and lymphatic endothelium.11,15,16 Based on its preferential chemotactic activity to naı̈ve T lymphocytes, its expression in the high endothelial venules (HEV) and T-cell areas within lymphoid tissues and its ability to stimulate lymphocyte adhesion to ICAM-1, SLC has been postulated to be a lymphoid tissue homing chemokine for lymphocytes.15

We report here that SLC is also a potent chemokine for mature DC and may be an additional cue guiding the migration of DC to secondary lymphoid organs. Given its chemotactic activity to both mature DC and T cells, SLC may serve as an important colocalization signal for these cells during early phases of the cellular immune response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemokines and Antibodies

Human recombinant SLC (molecular weight [MW] = 12 kD), ELC (MW = 8.8 kD), and RANTES (MW = 7.8 kD), as well as phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-human CCR6 antibodies, were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). PE-conjugated anti-human CD1a, CD14, and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-human CD86, CD40, and HLA-DR antibodies were obtained from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). PE-conjugated anti-human CD83 was obtained from Immunotech/Coulter (Miami, FL).

Generation of DC

DC were derived from peripheral blood monocytes as previously described.17 Buffy coats from healthy donors were obtained from the Blood Center of the Pacific (San Francisco, CA). CD14+ monocytes were isolated by negative depletion using Monocyte Isolation Kits along with MACS columns (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Cells were cultured at 0.6 × 106 per mL in medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum [FCS] [Summit, Fort Collins, CO], 2 mmol/L glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin) containing 1,000 U/mL recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (rhGM-CSF) (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) and 1,000 U/mL rhIL-4 (Peprotech). Fresh culture medium with cytokines was added every 2 days. Monocyte-conditioned medium (MCM) was prepared as previously described17 and was added to DC cultures at 30% on either the 5th or 6th day after culture initiation for 3 additional days. In some experiments, cells were matured using 50 ng/mL recombinant human TNF-α (Chiron, Emeryville, CA) instead of MCM. Expression of surface markers upon MCM-treatment was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Chemotaxis Assays

Migration assays were performed as described previously,18with slight modifications. Briefly, 10,000 to 15,000 cells were added to each of the top chamber of 96-well microchemotaxis plates (101-5 Neuroprobe, Cabin John, MD). Microchemotaxis plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. The number of cells in the bottom chamber was measured using the Cell Proliferation Reagent WST-1 (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Each measurement was set up in triplicate and the average values and standard deviation were calculated. In some measurements the cells were preincubated with 100 ng/mL of pertussis toxin (PT) for 2 hours at 37°C.

Calcium Mobilization

Cells were incubated at 106 per mL of medium (see above) plus 10 mmol/L HEPES with 2 μmol/L Fluo-3AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at 37°C for 30 minutes. Cells were washed and subsequently incubated with 1 μg/mL propidium iodide for 15 minutes at room temperature. Cells were washed again and were resuspended at 4 × 105 per mL in medium with 10 mmol/L HEPES. Fluo-3 fluorescence of viable cells (based on propidium iodide exclusion) was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Flow Cytometric Analysis

Analysis was performed on a fluorescence-activated cell sorter, FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and the data acquired to a Macintosh 7100 (Cupertino, CA) running CellQuest v3.1 software. The acquired data was analyzed and displayed using FlowJo (Tree Star Inc, San Carlos, CA).

Quantification of RNA Expression by Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) and Light Cycler

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from cells using Trizol reagent (GIBCO/BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After treatment with RNase-free DNase, first-strand cDNA was synthesized by priming with oligo-dT12-18 using SuperScriptII Preamplification System (GIBCO/BRL) following the manufacturer’s protocol. After RNaseH treatment, the cDNA was quantitated by spectrophotometric methods. Based on the published human sequences for CCR1-9, CXCR1-5, CX3CR1, and three orphan receptors, PCR oligonucleotides targeted to the regions close to the 3′ end of the coding regions with the highest divergence among chemokine receptors were designed. The forward (f ) and reverse (r) primers, the expected fragment size, and the GenBank accession numbers for each gene is indicated as follows. CCR1 (f: TGACTCTGGGGATGCAAC, r: TCCACTCTCGTAGGCTTTCG, 538 bp, L10918). CCR2 (f: CCCTTATTTTCCACGAGGATGG, r: CGCTTGGTGATGTGCTTTCG, 407 bp, U03905). CCR3 (f: TGAGACTGAAGAGTTGTTTG, r: ATTGATAGGAAGAGAGAAGG, 280 bp, U51241). CCR4 (f: CAGCTCCCTGGAAATCAACATTC, r: CAGTCTTGGCAGAGCACAAAAAGG, 369 bp, X85740). CCR5 (f: CCAAAAGCACATTGCCAAACG, r: ACTTGAGTCCGTGTCACAAGCC, 136 bp, X91492). CCR6 (f: ATCCTGCCAGAGCGAAAAGC, r: CATTGTCGTTATCTGCGGTCTCAC, 248 bp, U68032). CCR7 (f: TGCCATCTACAAGATGAGCT, r: GGTGCTACTGGTGATGTTGA, 492 bp, L08176). CCR8 (f: TCTGAAGATGGTGTTCTACA, r: ACTTTTCACAGCTCTCCCTA, 486 bp, U45983). CCR9 (f: GCATGGGACCATTTGGAAGC, r: CAGTCATTTCCTCTTGGGCAGTAAG, 478 bp,Y12815). CXCR1 (f: CCTTCTTCCTTTTCCGCCAG, r: AAGTGTAGGAGGTAACACGATGACG, 512 bp, L19591). CXCR2 (f: CTTTTCCGAAGGACCGTCTACTC, r: TGTGCCCTGAAGAAGAGCCAAC, 545 bp, M73969). CXCR3 (f: AATACAACTTCCCACAGGTG, r: CAAGAGCAGCATCCACATCC, 391 bp, X95876). CXCR4 (f: GCTGTTGGCTGAAAAGGTGGTC, r: CACCTCGCTTTCCTTTGGAGA, 538 bp, X71635). CXCR5 (f: ACGTTGCACCTTCTCCCAAGAG, r: AGAGAGCCATTCAGCTTGCAGG, 299 bp, X68149). Bonzo (f: TTACCATGACGAGGCAATTTCC, r: ATAACTGGAACATGCTGGTGGC, 484 bp, af007545). V28 (f: TGAATGCCTTGGTGACTACCCC, r: GGAGAAATCAACGTGGACTGAGC, 456 bp,U20350). GPR5 (f: CTCCTCAATATGATCTTCTCCAT, r: TCTGCAGAAACAGGGTGAA, 438 bp, L36149). GPR-9-6 (f: GCCATGAGAGCACATACTTG, r: GCAGATGTCAATGTTGGTGGA, 441 bp, U45982). GAPDH primers were from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA) (no. 5406). For each PCR reaction, 0.5 μg of cDNA was used in 25-μL reactions containing 10 mmol/L Tris, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 50 mmol/L KCl, pH 8.3, 1.25 U Taq DNA polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim), 0.2 mmol/L dNTP, and 50 pmol of each primer. PCR reactions were performed at 94°C, 1 minute, 60°C, 1 minute, 72°C, 1 minute for 30 cycles and analyzed on 2% agarose gels. Some PCR reactions were performed with a 1-minute annealing step at 55°C instead of 60°C. The specificity of each pair of primers for their respective gene was confirmed by cloning each of the PCR products into pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) and sequence verified (data not shown).

Light cycler.

Optimal light cycling conditions were used for these semi-quantitative PCR reactions. Each light cycling reaction (10 μL) contained: 50 mmol/L KCl, 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl pH 8.3, 2.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 250 μg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.2 mmol/L dNTP, 1U DNA Taq Polymerase, 0.1 pmol of each primer, and 1:5,000 SYBR Green I (Molecular Probes). Four reactions were run for each primer set to establish a concentration curve (250 ng, 125 ng, 62.5 ng, and 31.25 ng cDNA) for dye intercalation calculations. The Light Cycler (Idaho Technology, Idaho Falls, ID) program consisted of one normalization cycle (65°C to 85°C to 95°C, hold 20 seconds), followed by 45 cycles of: denaturation (95°C for 5 seconds), annealing (3°C below Tm for 2 seconds) and extension (72°C for 30 seconds). The 45 cycles are followed by a single final step of: 60°C for 5 seconds, 95°C for 5 seconds, and 32°C for 20 seconds. Each pair of primers have 2°C or less difference in Tm and generated a product within the optimal range (100 to 500 bp) for SYBR Green I dye quantification. The sequences and annealing temperatures of the primers used are: CCR1 (f: CTTTTGGACCCCCTACAATTTGAC, r: AACCCAGCAGAGAGTTCATGCTC, 58°C), CCR2 (f: CTTCGTTGGGGAGAAGTTCAGAAGG, r: TGGAAGGCGTGTTTGTTGAAGTCAC, 62°C), CCR3 (f: TTGGAAATGACTGTGAGCGGAGC, r: TGAGCAAGTGCCTGTGGAAGAAGTG, 62°C), CCR4 (f: TGTTCACTGCTGCCTTAATCCCATC, r: TGGACTGCGTGTAAGATGAGCTGG, 60°C), CCR5 (f: CAGGTTGGACCAAGCTATGCAG, r: GTGGATCGGGTGTAAACTGAGC, 58°C), CCR6 (same as RT-PCR, 60°C), CCR7 (f: TCAACATCACCAGTAGCACCTGTG, r: CAGGTCCTTGAAGAGCTTGAAGAG, 58°C) and actin (f: CTTCCTTCCTGGGCATGGAG, r: GAACTAAGTCATAGTCCGCCTAG, 57°C). Because actin amplifications gave similar profiles for both the immature and mature DC cDNA samples, actin was used as a reference and all CCR samples were evaluated as to their abundance with respect to the actin of that cDNA sample.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Generation of Immature and Mature DC

Immature DC were derived from monocytes isolated from human peripheral blood using GM-CSF and IL-4. To generate mature DC, we treated the cells with MCM or TNF-α. MCM-treatment induced significant upregulation of markers associated with DC maturation such as CD86, CD83, and MHC class II surface expression. The mean fluorescence channels for DC without or with MCM-treatment were 417 and 3624 for CD86, 186 and 721 for CD83, 667 and 790 for CD40, 202 and 132 for CD14, 2401 and 2413 for CD1a, and 1242 and 3106 for HLA-DR, respectively. These cells were also tested in an allogeneic MLR assay and the average stimulation indices at a DC:T ratio of 1:100 were 17.6 and 47.2 for DC before and after MCM-treatment, respectively (data not shown). Therefore, the DC differentiated in this in vitro culture model resemble their in vivo counterparts by both immunophenotype and function.

SLC and ELC are Chemotactic to Mature DC

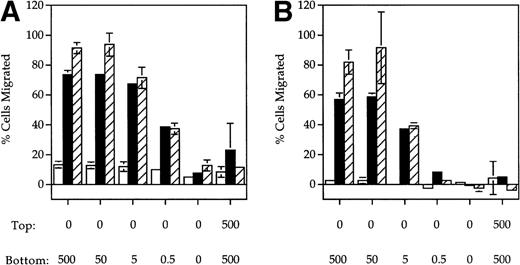

ELC, a chemokine expressed in secondary lymphoid organs,9,19,20 has previously been shown to be chemotactic for mature DC. SLC is another chemokine expressed in lymphoid tissues previously shown to be chemotactic for naı̈ve T cells. Because CCR7 is a shared receptor for SLC and ELC15,16,21 and is upregulated upon DC maturation,8-10 we tested whether SLC was also chemotactic to mature DC using a Boyden chamber assay. A dose-dependent increase in the migration of MCM-treated (mature) DC in response to both SLC (Fig1A) and ELC (Fig 1B) was observed. In contrast, mature DC did not respond to RANTES (Fig 1C), a chemokine previously shown to be chemotactic to immature DC.3 Similar results were also obtained with DC that were treated with TNF-α instead of MCM (Fig 1A and B). The migratory response of DC to SLC and ELC was dependent on the DC maturation stage because immature DC did not respond to either SLC or ELC (Fig 1A and B) but were able to migrate in response to RANTES (Fig 1C).

SLC and ELC but not RANTES induced chemotaxis of mature DC. (A and B) Migration of human monocyte-derived DC matured with MCM (▪) or TNF- (▨) compared to untreated immature cells (□), in response to the indicated concentrations (in ng/mL) of (A) SLC or (B) ELC. The percent migration (±SE) is based on the number of cells added to the top chamber. (C) Migration of MCM-treated mature DC or untreated (immature) DC in response to the indicated concentrations (in ng/mL) of RANTES. Chemotactic index is the ratio of the number of cells in the bottom chamber in the test case to the number of cells in the absence of the chemokine. (D) Preincubation with 100 ng/mL pertussis toxin (PT) inhibited SLC-induced migration of MCM-treated mature DC. These results are representative of at least three independent experiments.

SLC and ELC but not RANTES induced chemotaxis of mature DC. (A and B) Migration of human monocyte-derived DC matured with MCM (▪) or TNF- (▨) compared to untreated immature cells (□), in response to the indicated concentrations (in ng/mL) of (A) SLC or (B) ELC. The percent migration (±SE) is based on the number of cells added to the top chamber. (C) Migration of MCM-treated mature DC or untreated (immature) DC in response to the indicated concentrations (in ng/mL) of RANTES. Chemotactic index is the ratio of the number of cells in the bottom chamber in the test case to the number of cells in the absence of the chemokine. (D) Preincubation with 100 ng/mL pertussis toxin (PT) inhibited SLC-induced migration of MCM-treated mature DC. These results are representative of at least three independent experiments.

The migratory responses to SLC and ELC by mature DC were chemotactic and not due to chemokinesis because migration was not observed in the absence of a chemokine gradient (rightmost column, Fig 1A and B). Pretreatment of mature DC with pertussis toxin completely inhibited their migration toward both SLC and ELC (Fig 1D), suggesting that chemotaxis of mature DC by these two chemokines was mediated by Gαi coupled receptor(s).22

Mobilization of Intracellular Calcium by Mature DC in Response to SLC and ELC

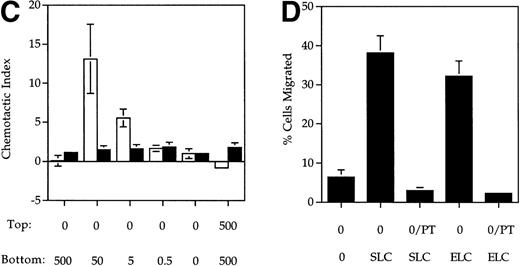

Because chemokines can cause rapid increases in intracellular calcium in responding cells,22 we next tested whether SLC and ELC induced calcium mobilization in mature and immature DC. SLC and ELC both induced rapid calcium mobilization in mature DC (Fig 2B and C), but not in immature DC (Fig 2A). In contrast, RANTES triggered a rapid calcium response in immature DC (Fig2A), but not in mature DC (Fig 2B and C). These results closely paralleled the differential chemotactic responses observed in migration assays (Fig 1). As with the chemotaxis response, the calcium responses of MCM-treated cells to SLC and ELC were dose dependent (Fig 2D and E).

Calcium mobilization in mature DC induced by SLC and ELC. DC (A) without or (B through E) with MCM-treatment were loaded with Fluo-3AM. The chemokines were added at the times indicated by the arrows and the calcium responses analyzed by flow cytometry. (A through C) Calcium responses to 500 ng/mL of SLC, ELC, or RANTES. (D and E) Dose-dependent calcium responses induced by 500, 150, 50, 15, 5, and 1.5 ng/mL of (D) SLC or (E) ELC. (F and G) Mature DC were loaded with Fluo-3AM and calcium mobilization was analyzed by flow cytometry. Concentration of the chemokines added were: (F) 100 ng/mL SLC, 500 ng/mL ELC, (G) 500 ng/mL ELC, 100 ng/mL SLC. These results are representative of two or more independent experiments.

Calcium mobilization in mature DC induced by SLC and ELC. DC (A) without or (B through E) with MCM-treatment were loaded with Fluo-3AM. The chemokines were added at the times indicated by the arrows and the calcium responses analyzed by flow cytometry. (A through C) Calcium responses to 500 ng/mL of SLC, ELC, or RANTES. (D and E) Dose-dependent calcium responses induced by 500, 150, 50, 15, 5, and 1.5 ng/mL of (D) SLC or (E) ELC. (F and G) Mature DC were loaded with Fluo-3AM and calcium mobilization was analyzed by flow cytometry. Concentration of the chemokines added were: (F) 100 ng/mL SLC, 500 ng/mL ELC, (G) 500 ng/mL ELC, 100 ng/mL SLC. These results are representative of two or more independent experiments.

Cross-Desensitization of SLC and ELC Induced Ca2+Mobilization

We have consistently observed that SLC induced a stronger calcium response in mature DC than ELC at equivalent doses (Fig 2). Also, SLC-induced migration of mature DC has an ED50 of 6 ng/mL while that for ELC was 35 ng/mL (Fig 1A and B). Taken together, these observations suggested that SLC from the vendor has a higher specific activity than ELC. Indeed, pretreatment of DC with 100 ng/mL of SLC was sufficient to completely inhibit the calcium response to 500 ng/mL of ELC (Fig 2F). Conversely, pretreatment with 500 ng/mL of ELC abrogated most of the SLC-induced calcium response (Fig 2G). It has previously been shown in CCR7-transfected cells that SLC and ELC can cross-desensitize each other in calcium mobilization.16,21These results indicated that SLC and ELC share similar signaling pathways in DC. It was recently reported that mature DC produce ELC in an autocrine fashion.10 Therefore, we also examined the mRNA expression of SLC in our immature and mature DC by RT-PCR but did not find either cell population to express SLC mRNA (data not shown).

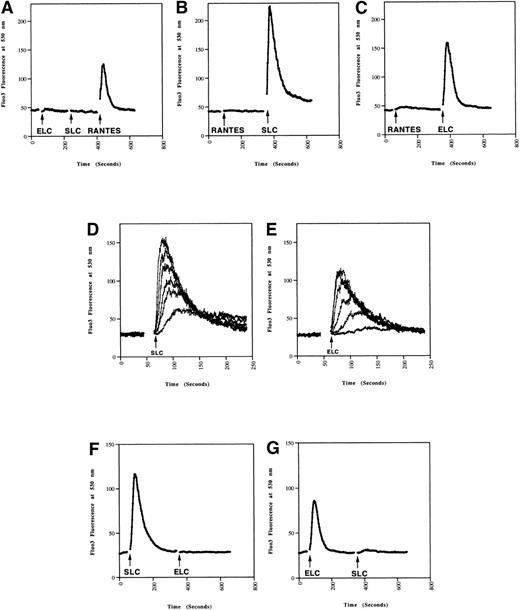

Chemokine Receptor mRNA Expression Before and After MCM-Treatment

The upregulation of CCR7 upon DC maturation8 9 originally prompted our investigation and led to our identification of SLC as a chemokine for mature DC. Given the usefulness of chemokine receptor upregulation as an indicator, a comprehensive survey of chemokine receptor expression on DC before and after MCM-treatment was performed. Significant increases in mRNA expression of CCR4, CCR7, and CXCR5/BLR1, as well as decreases in CCR1, CCR5, and CXCR2 were observed upon DC maturation (Fig3). CXCR1 expression was also consistently reduced upon MCM-treatment, despite a low basal level. A slight decrease in CCR2 and a slight increase in CCR8 were also observed, but no significant changes for CCR3, CCR6, CCR9, CXCR3, and CXCR4 were detected. No message for the orphan receptor GPR-9-6 was detected and there were no differences in the expression levels of CX3CR1, Bonzo, and GPR5 in mature and immature DC (data not shown). To confirm the validity of the semi-quantitative RT-PCR results, the expression levels of receptors reportedly involved in the binding of RANTES, ELC, and SLC (CCR1, 3-7) were examined using the Light Cycler, another semi-quantitative PCR method. As shown in Table1, the quantitative data from the Light Cycler closely parallel the trends observed with the results from agarose gel analysis (Fig 3).

Chemokine receptor expression profile in DC. Total RNA was prepared from DC after 8 days of culture, either untreated (−) or treated with MCM (+) from days 5-8. First-strand cDNA were synthesized and used in semi-quantitative PCR analysis. PCR products from 30 cycles of amplification were visualized on an ethidium-bromide–stained 2% agarose gel. Molecular-weight markers (in kb) are shown to the left of the gels. The annealing temperatures for all PCR reactions were 55°C except for CCR5, CCR6, CCR9, CXCR3, CXCR5, CX3CR1, which were at 60°C. These results are representative of seven or more experiments using three independent pairs of cDNA.

Chemokine receptor expression profile in DC. Total RNA was prepared from DC after 8 days of culture, either untreated (−) or treated with MCM (+) from days 5-8. First-strand cDNA were synthesized and used in semi-quantitative PCR analysis. PCR products from 30 cycles of amplification were visualized on an ethidium-bromide–stained 2% agarose gel. Molecular-weight markers (in kb) are shown to the left of the gels. The annealing temperatures for all PCR reactions were 55°C except for CCR5, CCR6, CCR9, CXCR3, CXCR5, CX3CR1, which were at 60°C. These results are representative of seven or more experiments using three independent pairs of cDNA.

Light Cycler Quantification of Chemokine Receptor Expression in cDNA From Immature and Mature DC

| Receptor . | Fold Change After MCM . |

|---|---|

| CCR1 | −4.3 |

| CCR3 | −2.1 |

| CCR4 | +3.3 |

| CCR5 | −3.1 |

| CCR6 | −1.5 |

| CCR7 | +24.0 |

| Receptor . | Fold Change After MCM . |

|---|---|

| CCR1 | −4.3 |

| CCR3 | −2.1 |

| CCR4 | +3.3 |

| CCR5 | −3.1 |

| CCR6 | −1.5 |

| CCR7 | +24.0 |

cDNA samples from immature (−MCM) or mature (+MCM) DC were used in light-cycle PCR reactions as described in Materials and Methods. The amount of product for each PCR reaction was calculated from the incorporation of SYBR green, and standardized to actin for individual cDNA samples. Results are expressed as the fold change upon addition of MCM. These data are representative of duplicates for one cDNA sample and repeats upon three independent sets of cDNA.

CCR6 RNA was previously reported to be undetectable in monocyte-derived DC.23,24 In contrast, we were able to detect CCR6 mRNA expression in our monocyte-derived DC but did not observe significant changes in expression upon MCM-treatment (Fig 3). We were also able to detect CCR6 mRNA expression in both immature and mature DC using the primers used by Power et al23 (data not shown). The identity of our PCR product was confirmed by direct sequencing, indicating that CCR6 was indeed expressed at the mRNA level (data not shown). However, flow cytometric analysis using anti-human CCR6 antibody indicated that there was no surface expression of CCR6 on either mature or immature DC (data not shown). Positive mRNA expression data but negative antibody staining has also been reported for other chemokine receptors in DC and may be due to the autocrine production of chemokines by mature DC resulting in receptor downregulation.10

The observation that CCR4 and CXCR5 are upregulated upon MCM-treatment of DC is intriguing because these two receptors have been shown to bind MDC (macrophage-derived chemokine)7,25 and BLC/BCA-1,26,27 respectively. MDC is expressed in the thymus and at a lower level in the spleen, and has been shown to be chemotactic for monocyte-derived DC.7 The mouse homologue of MDC was also found to be expressed in the T-cell area of the lymph node adjacent to the B-cell follicles.28 On the other hand, BLC is expressed in the follicles of Peyer’s patches, the spleen, and lymph nodes.27 Thus, the upregulation of CCR4 and CXCR5 may allow DC to sense additional chemokines guiding them for entry into secondary lymphoid organs. Once in secondary lymphoid organs, DC in turn may attract naı̈ve T cells by secreting chemokines such as DC-CK1,29 initiating immune responses. Randolph et al30 recently reported the differentiation of monocytes into DC upon traversing endothelial monolayers, a culture system that mimics the in vivo movement of DC from tissues into lymphatic vessels. It will be interesting to examine the receptor expression and the responses to chemokines in these DC.

In summary, we have shown that SLC is a chemoattractant for mature but not immature DC. The upregulation of CCR7 on DC upon MCM-treatment is consistent with this finding. The downregulation of receptors for inflammatory chemokines and the upregulation of receptors on mature DC for chemokines expressed in secondary lymphoid organs allow DC to leave the site of inflammation and antigen uptake to migrate to regional lymph nodes. Gunn et al31 have recently demonstrated a defect in DC localization in lymphoid organs in addition to a lack of T cells in T-cell zones32 in a strain of mice which lacks SLC expression and has reduced ELC expression. These, together with the observation that SLC is chemotactic for both mature DC and naı̈ve T cells, suggest that SLC may be an important factor for the colocalization of these two cell types to facilitate immune response initiation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Tim Brown and Marty Giedlin for our access to the FACS facility, and Mary Ellen Hammond, Gina Lapointe, Christoph Reinhard, and Mercedita Del Rosario for helpful advice on setting up the chemotaxis assays. We also thank Marty Giedlin and Xavier Paliard for critical reading of the manuscript, and Lucy Tang and M. Dee Gunn for helpful discussions.

V.W.F.C. and S.K. contributed equally to this article.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Lewis T. Williams, MD, PhD, Chiron Corporation, 4.6, 4560 Horton St, Emeryville, CA 94608; e-mail:rusty_williams@cc.chiron.com.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal