To the Editor:

The hereditary hyperferritinemia cataract syndrome (HHCS) is characterized by an elevated serum ferritin level without iron overload, and autosomal dominant congenital bilateral cataract. In 1995, Girelli et al1 identified a first mutation in the 5′ untranslated region of the L-subunit ferritin gene of an Italian family suffering from HHCS. This mutation was located in a critical sequence of the stem-loop motif known as iron-responsive element (IRE). IRE is a highly conservative structure that has been found in the 5′ untranslated region of all ferritin mRNAs, as well as in different regulatory areas of other iron-related homeostasis genes.2IRE is constituted by a six-nucleotide loop of consensus sequence 5′-CAGUGN-3′ and a paired stem with a small asymmetrical bulge. This structure has been shown to be critical for the posttranscriptional regulation of ferritin synthesis by means of IRE-binding protein (IRP). Subsequent changes in the IRE sequence have been described in several families from different countries of Europe in which HHCS was diagnosed. A number of IRE sequence substitutions have been shown to reduce protein binding affinity of IRP in vitro, producing L-ferritin accumulation as nonfunctional L-chain homopolymers either in lymphoblastoid cell lines or the lens.3 These findings have suggested that mutations in the IRE constitute the molecular basis in HHCS.

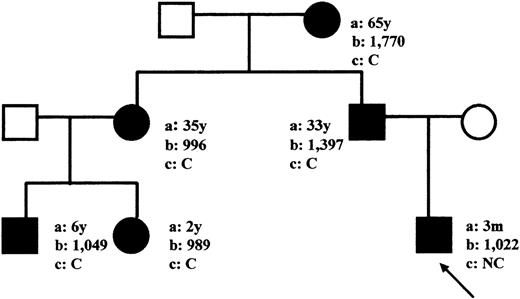

A healthy 3-month-old boy showed persistent hyperferritinemia (1,022 to 2,350 μg/L) in routine blood examinations when he was referred to our pediatric department with an infection. Serum iron and transferrin saturation levels were normal. His father, grandmother, aunt, and two cousins also suffered from hyperferritinemia (989 to 1,770 μg/L). Additionally, all except the proband suffered from congenital bilateral cataract, with visual symptoms appearing during the first decade. However, only the grandmother required surgery at the age of 60 (Fig1). The visual acuity of the remaining members affected by cataract was corrected with eyeglasses.

Pedigree of the family with HHCS. (Circles) Females; (squares) males; (closed symbols) affected members. Arrow indicates the proband. (a) Age at time of our observation (y, years; m, months). (b) Serum L-ferritin levels (μg/L). (c) Bilateral cataract status (C, cataracts; NC, no cataracts).

Pedigree of the family with HHCS. (Circles) Females; (squares) males; (closed symbols) affected members. Arrow indicates the proband. (a) Age at time of our observation (y, years; m, months). (b) Serum L-ferritin levels (μg/L). (c) Bilateral cataract status (C, cataracts; NC, no cataracts).

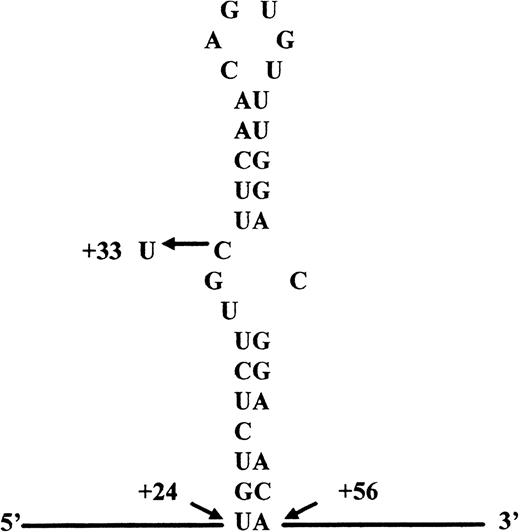

Sequence and proposed structure of the ferritin L-subunit IRE mRNA. The mutation found in the 5′ UGC bulge is indicated. Numbering is from the first transcripted nucleotide.

Sequence and proposed structure of the ferritin L-subunit IRE mRNA. The mutation found in the 5′ UGC bulge is indicated. Numbering is from the first transcripted nucleotide.

To carry out the molecular analysis of the L-chain ferritin gene, a 754-bp DNA fragment including the 5′ untranslated region, exons 1 and 2, as well as intron 1 and part of intron 2 was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Amplification primers were based on the L-ferritin sequence published by Santoro et al4 (GenBank accession no. X03742). DNA fragments were subsequently cloned and more than 10 clones from each patient were sequenced by automated DNA sequencing. Sequence analysis identified a point mutation, C to T, at position 33, according to the numbering of Cazzola et al,5in a half of the analyzed clones of all patients as an average (GenBank accession no. AF117958). This nucleotide substitution is located at the consensus three nucleotide bulge structure, positions 31-33 (Fig 2).

Correlation between genotype and phenotype has been suggested for HHCS.5 Mutations placed at the conserved loop are associated to higher ferritin concentrations and more severe cataracts than those found in the three-nucleotide motif forming the IRE bulge. Furthermore, nucleotide changes located at the lower stem have been associated with asymptomatic cataract and serum ferritin levels in the range of 350 to 650 μg/L. Therefore, three nucleotide substitutions have been described at the IRE bulge motif. The mutation termed Pavia 1, G to A at position 32, was associated with similar serum ferritin levels to those found in our studied family and a similar mild cataract with visual symptoms appearing during childhood.5 More recently, two French families have been described bearing the same G to T substitution at position 32, though displaying a marked variability in the age of onset of cataract between members of the two families.6

In conclusion, we have characterized a new mutation placed at the IRE sequence of the L-ferritin gene. This mutation is located at the bulge motif close to two different point substitutions previously described in three families that showed similar phenotypic characteristics to those found by us. These findings are in agreement with the observed correlation between genotype and phenotype in HHCS and increase the genotypic diversity of this disease.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal