Age is a risk factor and a prognostic parameter in elderly aggressive-histology non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) patients. Several adapted chemotherapeutic regimens have recently been designed and tested on elderly patients. Several of these trials have shown that older aggressive-histology NHL patients can benefit from specific and adequate treatment capable of curing a percentage of these patients. Between January 1992 and September 1997, 350 previously untreated aggressive-histology NHL patients greater than 60 years of age were treated with a combination therapy including cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone, vincristine, etoposide, bleomycin, and prednisone (VNCOP-B). Complete remission (CR) was achieved by 202 (58%) patients and partial remission (PR) by 87 (25%), whereas the remaining 61 (17%) patients were nonresponders. The overall response rate (CR + PR) was 83%. Clinical and hematologic toxicities were modest, because 71% of the patients received granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). The CR rates for the three age groups (60 to 69, 70 to 79, and ≥80 years) were similar: 61%, 59%, and 56%, respectively. At 5 years, the relapse-free survival rate was 65%, the overall survival rate was 49%, and the failure-free survival rate was 33%. In the multivariate analysis, prognostic factors associated with longer survival or longer relapse-free survival turned out to be localized disease stage (P = .001) and good performance status (P = .0002). Application of the International Prognostic Factor Index was significantly associated with outcome (P= .001). These data confirm on a large cohort of patients that the VNCOP-B regimen is effective in inducing good CR and relapse-free survival rates with only moderate toxic effects in elderly aggressive-histology NHL.

AMONG THE VARIOUS CLASSES of malignant disease, lymphomas have one of the most rapidly increasing incidences.1-3 In this group, aggressive-histology non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) presents a peak incidence in the age subset greater than 60 years. In addition, in line with the findings of large randomized trials that have shown constant cure rates for aggressive-histology NHL, but no further increase in cure rates with more intensive therapy during the last decades,4 5mortality rates have remained unchanged for younger people but have increased in elderly patients, the highest being observed in males older than 75 years.

Thus, in the last years, age has emerged as an important risk factor for aggressive-histology NHL.6-8 This observation could be explained by the fact that therapy is more toxic and the biology of the disease more aggressive in the elderly, and by the greater reluctance to diagnose and treat an elderly patient. Since the induction of primary complete remission (CR) has been successful in equivalent percentages of elderly and younger patients, it would seem that these two subgroups do not differ as regards tumor biology per se and chemosensitivity. In studies composed of nonselected patients, the worse outcomes for elderly patients could apparently be explained by higher toxicity of full-dose chemotherapy, age-associated comorbidity, and a lower response rate after relapse.9-11 Numerous attempts have been made to analyze the contribution to the age-related worsening of prognosis of factors, such as the biology of the disease, age-specific comorbidity (hypertension, depression, respiratory disease, diabetes, etc), and the degree of cytotoxicity (substantial alterations in pharmacokinetics of the drugs) with increased cardiotoxicity, pulmonary toxicity, and mucositis.

Recently, age-adapted treatment regimens, from first to third generation, have been designed and tested for their feasibility and efficacy in elderly aggressive-histology NHL patients.12-22In addition, progress has been made in defining maximally tolerated doses of the cytotoxic drugs and specifically testing anthracyclines with reduced cardiotoxicity,23-26 as well as in investigating the advantages of applying hematopoietic growth factors in this older population.

Since 1992, we have performed prospective studies on elderly aggressive-histology NHL patients using a treatment protocol developed at the “Seràgnoli” Institute in Bologna: an 8-week pilot regimen, the VNCOP-B protocol, using moderate doses of chemotherapy at frequent dosing intervals, obtained a good remission rate.27 Subsequently, we performed a multicenter randomized trial that included granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) as a further component of treatment to determine whether toxicity can be further reduced without sacrificing efficacy.28 In this report, we summarize the data concerning our entire experience with VNCOP-B regimen on 350 previously untreated elderly aggressive-histology NHL patients.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The present study regards 350 consecutive, previously untreated aggressive-histology NHL patients older than 60 years of age diagnosed between January 1992 and September 1997. It should be noted that 149 of these patients were previously presented in a randomized trial on the role of G-CSF.28 Eligibility criteria included a confirmed histologic diagnosis of aggressive-histology NHL according to the updated Kiel classification (Burkitt’s lymphomas and lymphoblastic lymphomas were excluded from this study)29; disease stage II to IV according to the Ann Arbor staging system30; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)31 performance status less than 3; human immunodeficiency virus–negative; and normal renal, hepatic, and cardiac functions. The diagnosis was reviewed by a panel of pathologists during the study period, and patients who did not fulfill all of the inclusion criteria were excluded from the final evaluation.

Staging evaluation included initial hematologic and chemical survey, in addition to chest x-rays, abdominal ultrasonography, computerized tomography of the chest and abdomen, and bone marrow biopsy in all patients. Other studies included lymphography, and liver biopsy when appropriate; no patient underwent staging laparotomy. Bulky disease was defined as a tumor mass ≥6 cm. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board for these studies. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient characteristics.

Characteristics of the 350 patients are listed in Table1. The median age was 69 years (range, 60 to 87); 55 (16%) patients were older than 80 years, and 12 (3.5%) were ≥85 years. A considerable percentage of patients had clinically aggressive disease: in particular, 65% had stage III or IV disease, 28% had a bulky disease, 25% had two or more extranodal sites, 18% had bone marrow involvement, and 35% had increased values of serum lactic dehydrogenase (LDH). The age-adjusted index, according to the International Prognostic Factor Index,6 was used, because all of the patients were older than 60 and, thus, the age parameter of the complete index was irrelevant. According to this index, 63 (18%) patients had no adverse factors, 137 (39%) had one factor, 109 (31%) had two factors, and 41 (12%) had three adverse parameters.

Clinical Characteristics and Therapeutic Results of 350 Elderly Patients With Aggressive-Histology NHL

| Age (yr) | |

| Median | 69 |

| Range | 60-87 |

| Sex (male/female) | 174/176 |

| Symptoms (no/yes) | 238/112 |

| Stage | |

| II | 123 (35%) |

| III | 79 (23%) |

| IV | 148 (42%) |

| Bulky disease | 98 (28%) |

| LDH (>normal) | 123 (35%) |

| Bone marrow involvement | 64 (18%) |

| Extranodal sites (no/yes) | 207/143 |

| Histology | |

| Centroblastic | 182 (52%) |

| Immunoblastic | 98 (28%) |

| Anaplastic large cell | 21 (6%) |

| Peripheral T cell | 49 (14%) |

| Result | |

| CR | 202 (58%) |

| PR | 87 (25%) |

| NR | 61 (17%) |

| Age (yr) | |

| Median | 69 |

| Range | 60-87 |

| Sex (male/female) | 174/176 |

| Symptoms (no/yes) | 238/112 |

| Stage | |

| II | 123 (35%) |

| III | 79 (23%) |

| IV | 148 (42%) |

| Bulky disease | 98 (28%) |

| LDH (>normal) | 123 (35%) |

| Bone marrow involvement | 64 (18%) |

| Extranodal sites (no/yes) | 207/143 |

| Histology | |

| Centroblastic | 182 (52%) |

| Immunoblastic | 98 (28%) |

| Anaplastic large cell | 21 (6%) |

| Peripheral T cell | 49 (14%) |

| Result | |

| CR | 202 (58%) |

| PR | 87 (25%) |

| NR | 61 (17%) |

Treatment protocol.

The VNCOP-B is a MACOP-B (methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, bleomycin)-like regimen32 with several distinctive features: treatment is completed in 8 weeks and includes mitoxantrone and etoposide instead of doxorubicin and methotrexate, respectively. We selected these replacements with the aim to reduce the incidence of mucositis and cardiac side effects. Drug doses, including prednisone (intramuscular or oral administration), were reduced by one third; all treatment was given on an outpatient basis. Doses and schedule of the VNCOP-B program are listed in Table2. The single-day dosing schedule of etoposide was chosen for logistic reasons. The G-CSF administration was 5 μg/kg/d subcutaneously throughout treatment, starting on day 3 of every week for 5 consecutive days. All patients received bacterial andPneumocystis carinii prophylaxis with cotrimoxazole (2 consecutive days per week) during the entire course of therapy.

Drug Doses and Treatment Schedule for VNCOP-B

| Drug . | Dose . | Route . | Timing . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclophosphamide | 300 mg/m2 | IV | Weeks 1, 3, 5, 7 |

| Mitoxantrone | 10 mg/m2 | IV | Weeks 1, 3, 5, 7 |

| Vincristine | 2 mg | IV | Weeks 2, 4, 6, 8 |

| Etoposide | 150 mg/m2 | IV | Weeks 2, 6 |

| Bleomycin | 10 mg/m2 | IV | Weeks 4, 8 |

| Prednisone | 40 mg | IM/oral | Daily, dose tapered over the last 2 wk |

| Drug . | Dose . | Route . | Timing . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclophosphamide | 300 mg/m2 | IV | Weeks 1, 3, 5, 7 |

| Mitoxantrone | 10 mg/m2 | IV | Weeks 1, 3, 5, 7 |

| Vincristine | 2 mg | IV | Weeks 2, 4, 6, 8 |

| Etoposide | 150 mg/m2 | IV | Weeks 2, 6 |

| Bleomycin | 10 mg/m2 | IV | Weeks 4, 8 |

| Prednisone | 40 mg | IM/oral | Daily, dose tapered over the last 2 wk |

Abbreviations: IV, intravenous; IM, intramuscular.

Response.

All patients were restaged after completion of chemotherapy. Clinical and pathologic evaluations were made by repeating radiographic investigations and bone marrow and/or liver biopsies if previous results had been positive. CR was defined as the total disappearance of signs and symptoms due to disease, as well as the normalization of all previous abnormal findings. Partial remission (PR) was defined as the reduction of at least 50% of known disease with disappearance of the systemic manifestations. No response (NR) was anything less than a PR. Standard ECOG toxicity criteria were used.31

Statistical methods.

The survival curve was measured from the time of entry into the protocol until death; the relapse-free interval was calculated from the date of response until relapse or death. Survival, relapse-free survival, and failure-free survival curves were calculated according to the method of Kaplan and Meier.33

Deaths from lymphoma, secondary to lymphoma treatment, or to a possibly related or unrelated disease were considered an event. Analyses of prognostic factors were performed with log-rank tests, Cox’s analysis,34 and logistic regression analysis.

RESULTS

Treatment outcome is summarized in Table 1. A CR was achieved by 202 of 350 (58%) patients, and PR by 87 (25%) patients, while the remaining 61 patients had NR. The overall response rate (CR + PR) was 83%. The CR rates for the three age groups (60 to 69, 70 to 79, and ≥80 years) were similar: 61%, 59%, and 56%, respectively.

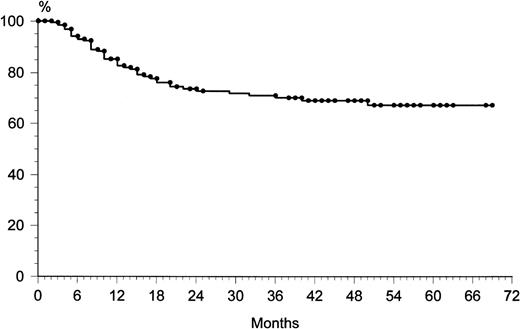

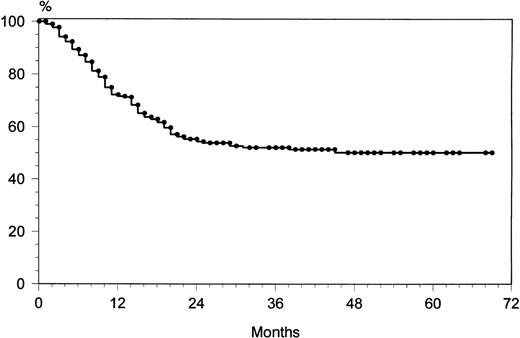

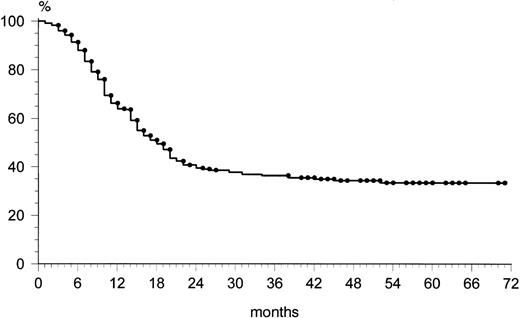

Among the 202 patients who achieved CR, 48 (24%) relapsed. The overall rate of relapse-free survival for the 202 patients with CR was 65% at 69 months (median, 36 months; range, 9 to 72) (Fig 1). The majority of relapses was observed within the first 24 months: 43 of 48 (90%). After 2 years, only five patients showed a relapse. The overall survival rate at 69 months was 49% (Fig2). The overall survival rates of the three age groups (60 to 69, 70 to 79, and ≥80 years) were similar: 53%, 51%, and 47%, respectively. At 69 months, the failure-free survival rate was 33% (Fig 3).

Toxic effects.

With regard to hematologic toxicity, the incidence of anemia and thrombocytopenia was less than 10% and transfusions were not required. Neutropenia less than 0.5 × 109/L occurred in 103 of 350 (29%) patients. These data are underestimated because in 248 of 350 (71%) patients, we used G-CSF with a subcutaneous administration throughout the treatment, starting on day 3 of every week for 5 consecutive days. The same consideration has to be made for the frequency of clinically relevant infections: in fact, patients who received G-CSF showed a significantly lower incidence of neutropenia with the reduction of the number of infections. Globally, clinically relevant infections were recorded in 39 of 350 (11%) patients. Nonhematologic toxicity was minimal. Mild mucositis was observed in a few patients. Cardiac, liver, and renal problems were not observed. There were only four (1%) fatalities due to drug side effects during the treatment period (two from sepsis, one gastric hemorrhage, and oneP carinii infection). Four patients died of solid neoplasms (one liver, one pancreas, one meningioma, and one melanoma).

Statistical analysis.

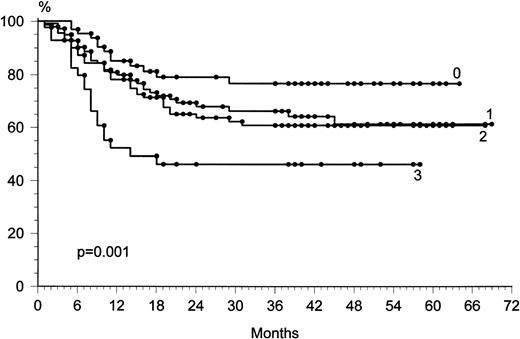

To evaluate whether any covariate prognostic factor could influence the outcome of CR, adjustment for the prognostic factors was performed by the linear logistic model. Information on nine prognostic factors (age, sex, presence or absence of B symptoms, stage, LDH level, presence or absence of bulky disease, extranodal sites, histologic subtype, and performance status) was associated with the outcome of all of the patients (Table 3). Lower CR rate was correlated to the presence of bulky disease (P = .02), poor performance status (P = .01), and advanced stage (P = .01). The prognostic factors associated with longer relapse-free survival in univariate analyses (log-rank test) were localized disease stage (P = .001 and P = .002, respectively), good performance status (P = .0001 and P= .0001), and normal LDH level (P = .03 and P = .01). In a Cox multivariate analysis, the prognostic factors most significantly associated with longer survival or longer relapse-free survival were localized disease stage (P = .001) and good performance status (P = .0002). The International Prognostic Factor Index6 was significantly associated with outcome (P = .001) (Fig 4).

CR and Survival Outcome According to Prognostic Factors

| Factor . | No. of Patients . | CR Rate (%) . | 5-Year Overall Survival (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | |||

| 60-69 | 189 | 61 | 53 |

| 70-79 | 94 | 59 | 51 |

| ≥80 | 67 | 56 | 47 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 174 | 57 | 48 |

| Female | 176 | 59 | 50 |

| B symptoms | |||

| Absent | 238 | 60 | 50 |

| Present | 112 | 57 | 47 |

| Stage | |||

| II | 123 | 66 | 57 |

| III-IV | 227 | 51 | 39 |

| LDH level | |||

| Normal | 227 | 61 | 53 |

| Above upper normal limit | 123 | 56 | 43 |

| Bulky disease | |||

| Absent | 252 | 68 | 55 |

| Present | 98 | 49 | 41 |

| Extranodal sites | |||

| Absent | 207 | 62 | 50 |

| Present | 143 | 55 | 48 |

| Histologic subtype | |||

| Centroblastic | 182 | 63 | 52 |

| Immunoblastic | 98 | 60 | 47 |

| Anaplastic large cell | 21 | 57 | 48 |

| Peripheral T cell | 49 | 55 | 46 |

| Performance status | |||

| 0-1 | 212 | 67 | 56 |

| 2 | 138 | 50 | 40 |

| Factor . | No. of Patients . | CR Rate (%) . | 5-Year Overall Survival (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | |||

| 60-69 | 189 | 61 | 53 |

| 70-79 | 94 | 59 | 51 |

| ≥80 | 67 | 56 | 47 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 174 | 57 | 48 |

| Female | 176 | 59 | 50 |

| B symptoms | |||

| Absent | 238 | 60 | 50 |

| Present | 112 | 57 | 47 |

| Stage | |||

| II | 123 | 66 | 57 |

| III-IV | 227 | 51 | 39 |

| LDH level | |||

| Normal | 227 | 61 | 53 |

| Above upper normal limit | 123 | 56 | 43 |

| Bulky disease | |||

| Absent | 252 | 68 | 55 |

| Present | 98 | 49 | 41 |

| Extranodal sites | |||

| Absent | 207 | 62 | 50 |

| Present | 143 | 55 | 48 |

| Histologic subtype | |||

| Centroblastic | 182 | 63 | 52 |

| Immunoblastic | 98 | 60 | 47 |

| Anaplastic large cell | 21 | 57 | 48 |

| Peripheral T cell | 49 | 55 | 46 |

| Performance status | |||

| 0-1 | 212 | 67 | 56 |

| 2 | 138 | 50 | 40 |

Overall survival with respect to the International Prognostic Factor Index.

DISCUSSION

During the last several years it has become clear that the treatment of elderly aggressive-histology NHL patients has been underevaluated, with confounding factors being caused not only by prejudice on the part of patients, but sometimes also by the attitudes of specialists. The increasing efforts in analyzing the contribution of these factors to the inferior treatment outcome of older aggressive-histology NHL patients is therefore a major prerequisite in a more scientific approach to developing treatment protocols specifically adapted to the situations of elderly subjects. In this context, scientifically reproducible (rather than individualized) estimations of a patient’s comorbidity, fitness, and natural life expectancy are required. In addition, ways of determining the quality of life of a given subject that move from the patient’s and not the physician’s viewpoints will have to be developed.

Back in the days of first-generation chemotherapeutic regimens, when in a Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) study CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) chemotherapy was reduced by 50% in patients over 65 years of age, CR rates declined.35However, in a small subset of patients over 65 years of age who received full doses, the CR rate approximated that of younger patients. Fisher et al4 subsequently indicated that the gold-standard regimen for elderly aggressive-histology NHL patients was CHOP. However, at full dosage, the percentage of toxic deaths increased, while the CR rate decreased when the doses were reduced. Recently, three prospective, randomized studies36-38 have shown that the standard CHOP regimen can be given in sufficient doses to elderly aggressive lymphomas obtaining CR rates of 45%,3849%,37 or 68%.36 In these studies, the treatment-related mortality rate was between 0% and 15%.

Pirarubicin, an anthracycline supposed to display reduced cardiotoxicity, has also been used in place of doxorubicin. As shown by the data of the randomized Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte (GELA) study,23 the pirarubicin-containing CTVP regimen was superior to CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone), despite its higher level of toxicity. CTVP produced a CR rate of 47% with a treatment-related mortality rate of 15%.

Full dosage second- and third-generation protocols appear to be too intensive to be administered to elderly aggressive-histology NHL patients without significantly escalating toxicity. Nevertheless, new protocols specifically tailored to the tolerance and the biologic (rather than calendar) age of patients have been reported to produce functional lymphoma therapy in the elderly.11-22 All of these regimens were characterized by a shorter duration and by the use of doxorubicin-free protocols to reduce the incidence of cardiotoxicity. Among these adapted regimens, the CR rate ranged between 45% and 75%. In particular, third-generation protocols usually combine myelosuppressive and nonmyelotoxic medications in rapid alternation with the aim of reducing the risk of cross-reactivity together with the length of treatment while maintaining or enhancing dose-intensity.

In 1993, we reported that VNCOP-B (a MACOP-B-like methotrexate-and doxorubicin-free regimen) was generally well tolerated, with 85% of patients able to complete all courses of therapy at the full dose; the overall response rate was 93% with a CR rate of 76%.27Following this, we have set out to confirm these preliminary data in a multicenter prospective study and to evaluate the role of G-CSF in this protocol in a randomized trial. In 1997, we reported that the VNCOP-B CR rate was 59% and that G-CSF turned out to be effective in reducing the neutropenia and infection rates.28 Other reports have shown that hematopoietic growth factors can reduce hematologic toxicity in this subset of patients.39-41

The present global evaluation of all 350 elderly aggressive-histology NHL patients who received the VNCOP-B regimen as first therapy showed a CR rate of 58% without statistically significant modifications of the CR rate among the different age subgroups (60 to 69, 70 to 79, and ≥80 years). The 5-year relapse-free rate was 65%, with a median of 36 months, and the 5-year overall survival rate was 49%, with a failure-free survival rate of 33%. The drug-related death rate was only 1%. The International Prognostic Factor Index6 was significantly associated with outcome.

On the basis of these data on a large cohort of patients, some observations are apparent: (1) the VNCOP-B regimen is effective in elderly patients with advanced aggressive-histology NHL, with a CR rate only slightly lower than that obtained in younger aggressive-histology NHL patients; (2) the complete responders have a good probability of a long-term survival; and (3) considering the few cases of clinical toxicity, VNCOP-B treatment is well tolerated (with the inclusion of G-CSF) and there is no evidence of severe or permanent toxic effects. With the aim of reducing the gap between the older and younger aggressive-histology NHL and also among the different prognostic subgroups of elderly patients, we have recently started a prospective comparative study between 8-week VNCOP-B and 12-week VNCOP-B (with the inclusion of G-CSF in both protocols) in order to evaluate CR, overall survival, and relapse-free survival rates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Robin M.T. Cooke for language editing.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Pier Luigi Zinzani, MD, Istituto di Ematologia e Oncologia Medica “Seràgnoli,” Policlinico S. Orsola, Via Massarenti 9 40138 Bologna, Italy.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal