Abstract

Infection by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) either upregulates or downregulates the expression of several cytokines and interferons (IFNs) that use the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway for signal transduction. However, very little is known on the state of activation of the JAK/STAT pathway after HIV infection either in vivo or in vitro. In this regard, we report here that a constitutive activation of a C-terminal truncated STAT5 (STAT5▵) and of STAT1 occurs in the majority (∼75%) of individuals with progressive HIV disease. We have further demonstrated that, among peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), STAT5▵ is activated preferentially in CD4+ T cells. In contrast to a published report, expression of STATs from PBMCs of infected individuals was comparable with that of seronegative donors. In addition, in vitro infection of mitogen-activated PBMCs with a panel of laboratory-adapted and primary HIV strains characterized by differential usage of chemokine coreceptors did not affect STAT protein levels. However, enhanced activation of STAT was observed after in vitro infection of resting PBMCs and nonadherent PBMCs by different viral strains. Thus, constitutive STAT activation in CD4+T lymphocytes represents a novel finding of interest also as a potential new marker of immunological reconstitution of HIV-infected individuals.

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY virus (HIV) infection leads to a progressive deterioration of the human immune system. In this regard, one of the early clinical manifestations of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is the loss of both memory and naive CD4+ T cells coinciding with a state of chronic T-cell activation that favors apoptosis or anergy of both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets.1Consequently, these cells lose the capacity of controlling HIV infection.2 Among other mechanisms, both cytokines and interferons (IFNs) play a pivotal role in regulating proliferation, differentiation, and activation of the immune cells through the triggering of multiple intracellular signaling pathways.3,4Among these, the far most studied and better-characterized is the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway,4,5 a very rapid membrane-to-nucleus signaling system, based on the activation of the cytosolic latent transcription factors STATs by JAK-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation. STATs ultimately dimerize and translocate to the nucleus and activate cytokine-inducible gene transcription.5

Numerous studies indicate that several cytokines may have a direct or indirect effect on HIV-infected cells by exerting either inductive, suppressive, or bifunctional effects on virus replication.1,6 In this regard, we have recently provided evidence indicating a clear role of the IFNγ- and IFNα-mediated JAK/STAT pathways in inhibiting HIV replication in a human monocytic system.7 Conversely, HIV replication or expression of viral genes causes a profound dysregulation of the cytokine network, which may play an important role in disease progression by impairing anti-HIV immune responses.1,6 Quite surprisingly, very little is known on whether HIV infection in vitro or in vivo can result in the perturbation of the JAK/STAT pathway.8 In support of this hypothesis, stimulation of glial cells by HIV gp120 envelope (Env) glycoprotein has been shown to induce STAT1 and JAK2 activation.9 More recently, gp120 Env binding to CD4 has been reported to result in the inhibition of interleukin-2 receptor (IL-2R) expression and proliferation in T lymphocytes, effects that have been correlated with the inhibition of both expression and activation of JAK3.10 Finally, Pericle et al11have reported a selective reduction of STAT5b expression in phytohemagglutinin (PHA) blasts infected in vitro by the HIV-1BZ167 dual-tropic isolate, but not by the HIV-1BaL M-tropic strain, along with a reduced expression of STAT5a, STAT5b, and STAT1α in T cells purified from HIV-infected individuals. Unfortunately, no information on the state of activation of STAT in HIV-infected individuals was provided in this study.11

The aim of our study was to investigate the possible effect of HIV infection on STAT activation and expression both in HIV-infected individuals and after in vitro infection of resting and activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) by a panel of different HIV strains differing for chemokine coreceptor usage. Our study provides compelling evidence for a constitutive in vivo activation, mainly of a truncated isoform of STAT5 and STAT1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Sixteen HIV-seropositive individuals observed at the “Centro San Luigi” Hospital (Milan, Italy) were studied after informed consent had been obtained. All HIV-infected patients had CD4 counts greater than 200/μL. Five patients were naive for antiretroviral therapy, whereas 11 patients had been treated with different antiretroviral regimens at the time of the analysis. The main clinical parameters of these individuals are reported in Table 1.

Clinical and Laboratory Findings of HIV-1–Infected Patients

| Patient No. . | Age (yr)/ Sex . | CD4+ (cells/μL) . | CD8+ (cells/μL) . | CD4+/CD8+ . | Viremia (RNA copies/mL) . | Therapy . | STAT Activation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30/F | 400 | 374 | 1.06 | <400 | NA | + |

| 2 | 34/M | 714 | 1,039 | 0.68 | 32,661 | NA | + |

| 3 | 35/M | 559 | 851 | 0.65 | <400 | NA | + |

| 4 | 35/M | 326 | 1,410 | 0.23 | 233,063 | NA | + |

| 5 | 41/M | 480 | 3,473 | 0.13 | 108,294 | ddI, AZT | + |

| 6 | 40/M | 206 | 1,630 | 0.12 | 100,828 | d4T | + |

| 7 | 45/M | 477 | 497 | 0.95 | 947 | ddI + 3TC | + |

| 8 | 23/F | 332 | 286 | 1.1 | <400 | AZT + ddI | + |

| 9 | 62/F | 510 | 384 | 1.33 | 93,814 | AZT + 3TC | + |

| 10 | 45/F | 339 | 571 | 0.59 | 111,932 | AZT + ddI | + |

| 11 | 47/M | 382 | 685 | 0.55 | 134,688 | d4T + ddI | − |

| 12 | 45/M | 273 | 803 | 0.33 | 37,791 | AZT + ddI | − |

| 13 | 40/M | 335 | 1,041 | 0.32 | 23,253 | AZT + ddI | − |

| 14 | 46/M | 620 | 1,514 | 0.40 | 4,360 | NA | − |

| 15 | 31/F | 517 | 1,716 | 0.30 | <400 | Triple | + |

| 16 | 54/M | 427 | 1,076 | 0.39 | <400 | Triple | + |

| Patient No. . | Age (yr)/ Sex . | CD4+ (cells/μL) . | CD8+ (cells/μL) . | CD4+/CD8+ . | Viremia (RNA copies/mL) . | Therapy . | STAT Activation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30/F | 400 | 374 | 1.06 | <400 | NA | + |

| 2 | 34/M | 714 | 1,039 | 0.68 | 32,661 | NA | + |

| 3 | 35/M | 559 | 851 | 0.65 | <400 | NA | + |

| 4 | 35/M | 326 | 1,410 | 0.23 | 233,063 | NA | + |

| 5 | 41/M | 480 | 3,473 | 0.13 | 108,294 | ddI, AZT | + |

| 6 | 40/M | 206 | 1,630 | 0.12 | 100,828 | d4T | + |

| 7 | 45/M | 477 | 497 | 0.95 | 947 | ddI + 3TC | + |

| 8 | 23/F | 332 | 286 | 1.1 | <400 | AZT + ddI | + |

| 9 | 62/F | 510 | 384 | 1.33 | 93,814 | AZT + 3TC | + |

| 10 | 45/F | 339 | 571 | 0.59 | 111,932 | AZT + ddI | + |

| 11 | 47/M | 382 | 685 | 0.55 | 134,688 | d4T + ddI | − |

| 12 | 45/M | 273 | 803 | 0.33 | 37,791 | AZT + ddI | − |

| 13 | 40/M | 335 | 1,041 | 0.32 | 23,253 | AZT + ddI | − |

| 14 | 46/M | 620 | 1,514 | 0.40 | 4,360 | NA | − |

| 15 | 31/F | 517 | 1,716 | 0.30 | <400 | Triple | + |

| 16 | 54/M | 427 | 1,076 | 0.39 | <400 | Triple | + |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable (naive individuals); Triple, triple therapy, 2 reverse transcriptase inhibitors (RTI) + 1 protease inhibitor (PI).

Cell separation, cell culture, and PBMC subsets separation.

Peripheral venous blood was collected from HIV+ patients and from 6 healthy seronegative donors on both heparin and EDTA. PBMCs were prepared by centrifugation on a Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden), as previously described.12 Aliquots of 1 × 106 cells were washed twice in RPMI 1640 medium, and pellets were obtained by centrifugation at 13,000g for 10 minutes and then frozen at −80°C for further analyses.

Monocytes (MΦ) were separated from freshly isolated PBMCs of normal uninfected donors by adherence onto plastic for 1 hour at 37°C in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% human AB serum (BioWhittaker, Verviers, Belgium). Nonadherent PBMCs (NA-PBMCs) were removed from the flask and, after 2 washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), seeded at 1 × 106 cells/mL in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2 mmol/L glutamine, penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL; BioWhittaker), and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; HyClone Europe, Ltd, Cramlington, UK). Adherent MΦ were washed twice with warm medium and further cultivated in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS and 10% human AB serum.

PHA blasts were prepared from PBMCs of normal donors resuspended at the density of 1 × 106 cells/mL in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS and stimulated by PHA (5 μg/mL; Sigma Chemical Corp, St Louis, MO) for 3 days. Cells were then washed 3 times with PBS and seeded in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS and recombinant IL-2 (20 U/mL; Roche Diagnostics, SpA, Monza, Italy) at the density of 1 × 106 cells/mL.

In some experiments, CD4+ and CD8+ cells were depleted from PBMCs of HIV-infected patients by using immunomagnetic beads coated with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody (MoAb; Dynatech, Dynal, Oslo, Norway) following the manufacturer's instructions. Cell phenotype was determined by cytofluorimetry after immunostaining with anti-CD3/CD4 and anti-CD3/CD8 MoAb (Coulter Corp, Hialeah, FL) by a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and analyzed using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson).

Quantification of viral RNAs in plasma.

Plasma viremia was measured by the Amplicor Monitor kit (Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, NJ) following the manufacturer's instructions.

HIV infection and reverse transcriptase (RT) assay.

PHA blasts from normal uninfected donors were acutely infected in vitro with 6 HIV-1 strains, characterized by different cellular tropism and chemokine coreceptor use,13 at a multiplicity of infection (moi) of 0.1. Three laboratory-adapted (HIV-1IIIB/LAI[T-tropic, X4], HIV-1BaL [M-tropic, R5], and HIV-189.6 [multi-tropic, X4/R5/R2/R3]) and 3 primary isolates (DU [dual-tropic X4/R5], SA [dual-tropic X4/R3], and BC [multi-tropic X4/R5/R2]) were independently adsorbed to the cells for 1 hour at 37°C. Cells were then resuspended in complete medium and seeded (1 × 106 cells/well) in duplicate wells in 48-well polystyrene culture plates (Falcon, Becton Dickinson Labware, Lincoln Park, NJ). Culture supernatants were harvested every 4 days and stored at −80°C until tested for Mg2+-dependent RT-activity assay, as previously described.14 Primary HIV isolates were established by cocultivation of HIV-infected patients' PBMCs with PHA blasts of uninfected individuals. Chemokine coreceptor usage was tested on U87 astrocytic cells stably transfected with human CD4 alone or together with one of the following human chemokine receptors (as reported15): CXCR4, CCR2B, CCR3, and CCR5 (kindly provided by D. Littman, Skirball Institute, New York, NY). Resting PBMCs, NA-PBMCs, and MΦ were exposed in vitro to 0.1 moi of HIV-1IIIB/LAI and HIV-1BaL strains.

Abs.

Affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal Abs raised against a C-terminal (residues 711-727; sc-835) or an N-terminal (residues 5-24; sc-836) epitope of STAT5 and the affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal Abs raised against the C-terminal domain of JAK3 (sc-513) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc (Santa Cruz, CA); the pan-STAT5-reactive MoAb raised in mouse against an internal epitope (residues 451-649) was purchased from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY); rabbit polyclonal Abs raised against C-terminal epitopes of STAT5a and STAT5b16 were a generous gift from R.A. Kirken (Laboratory of Molecular Immunoregulation, National Cancer Institute, Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center, Frederick, MD); anti-STAT1α rabbit polyclonal Ab raised against amino acids 741-750 was a generous gift from K. Ozato (Laboratory of Molecular Growth Regulation, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD); and rabbit polyclonal Ab against human actin (A2066) was purchased from Sigma.

Whole-cell extracts (WCEs) and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

WCEs were prepared by repeated cycles of freezing and thawing. Fresh or frozen cell pellets were resuspended in a high salt buffer (buffer C, 20 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.9, 400 mmol/L NaCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L EGTA, 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol [DTT], 10% [vol/vol] glycerol) supplemented with a cocktail of protease inhibitors that included leupeptin (10 μg/mL), pepstatin A (10 μg/mL), aprotinin (33 μg/mL), E-64 (10 μg/mL), AEBSF (1 mmol/L), diisopropyl fluorophosphate (DFP; 3 mmol/L), and the phosphatases inhibitors sodium vanadate (Na3VO4; 1 mmol/L), sodium fluoride (NaF; 50 mmol/L), and 0.5% Nonidet P-40. Cell disruption was achieved by 3 freeze-and-thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 12,000g for 15 minutes at 4°C, and the resulting supernatants were aliquoted and stored at −80°C before use. Protein concentration was evaluated by a protein assay kit based on the Bradford method (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

For EMSA, WCEs were incubated with different [γ-32P]ATP-end-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotides corresponding to either the prolactin-responsive element (PRE) located within the promoter of the β-casein promoter,17 the IFNγ-responsive region (GRR) located within the promoter of the FcγRI gene, or the high-affinity synthetic derivative of the c-sis–inducible element (SIE), hSIE-m-67,18 and the DNA-protein complexes were resolved as previously described.18 In selected experiments, the radiolabeled double-stranded oligonucleotide corresponding to the Ying Yan (YY1) binding site located within the Moloney murine leukemia virus promoter (UCR)19 was added to the binding mixture together with the PRE probe to verify that similar amounts of proteins were used in each sample.

Immunoblot analyses.

Cellular proteins were denatured by the addition of an equal volume of sample buffer 2× (50 mmol/L Tris-base, pH 6.8, 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 10% 2-β-mercaptoethanol, and 20% glycerol) and heated for 5 minutes at 100°C before electrophoretic separation on 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and subsequent transfer to nitrocellulose membrane Hybond enhanced chemiluminescence system (ECL; Amersham, Little Chalfont, UK) by electroblotting. Membranes were blocked in 7.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 20 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.6, 137 mmol/L NaCl, and 0.2% Tween 20 for 1 hour at room temperature and further incubated (overnight at 4°C) with the desired primary Ab. Anti-STAT5 C- or N-terminal Abs were diluted 1:1,000, whereas anti-STAT5 MoAb and anti-actin Abs were diluted 1:250 and 1:500, respectively, as recommended by the manufacturers. Ab binding was visualized by using the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary Ab (antimouse or antirabbit Abs, diluted 1:5,000 or 1:15,000, respectively). The signal was shown by the ECL (Amersham) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RESULTS

Constitutive activation of STATs in HIV+ patients.

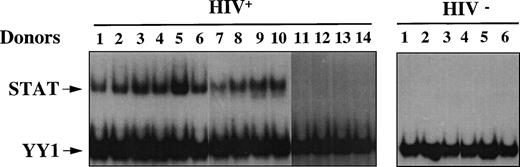

We analyzed WCEs obtained from unstimulated PBMCs of either HIV+ or HIV− individuals by EMSA using a STAT-specific radiolabeled probe corresponding to the PRE, in combination with a YY1-specific radiolabeled probe corresponding to the UCR element. Because YY1 is a ubiquitously expressed nuclear transcription factor, the UCR probe was included to verify that equal amounts of proteins were present in the extracts of each sample (Fig 1). We examined a total of 14 HIV+ patients with progressive disease, 9 of whom were under antiretroviral therapy and 5 who were naive subjects. In addition, PBMCs were prepared from 6 healthy seronegative donors. Eight of 9 (89%) and 4 of 5 (80%) HIV+ individuals, treated and untreated with antiretrovirals, respectively, but none of the healthy controls, as expected, showed activation of STATs, as shown in Fig 1. No significant difference in YY1 binding was observed, indicating that equal amounts of proteins were loaded in all samples. Similar results were obtained using oligonucleotides corresponding to binding elements with selectivity for different STATs, such as the GRR and the hSIE-m67 (data not shown). In this regard, PRE binds preferentially STAT5 but also STAT1, whereas GRR preferentially recognizes STAT1 and STAT5 and, finally, hSIE/m-67 exclusively recognizes STAT1 and STAT3. Thus, a constitutive STAT-DNA binding activity was observed in vivo in most HIV-infected individuals.

Constitutive activation of STAT in HIV+patients. EMSA using WCEs (8 μg), obtained from PBMCs isolated from 6 healthy HIV− and 14 HIV+ individuals, and a mixture of PRE and UCR radiolabeled oligonucleotides. Constitutive YY1-DNA binding serves as a control.

Constitutive activation of STAT in HIV+patients. EMSA using WCEs (8 μg), obtained from PBMCs isolated from 6 healthy HIV− and 14 HIV+ individuals, and a mixture of PRE and UCR radiolabeled oligonucleotides. Constitutive YY1-DNA binding serves as a control.

A truncated STAT5 isoform and STAT1α are constitutively activated in HIV+ individuals.

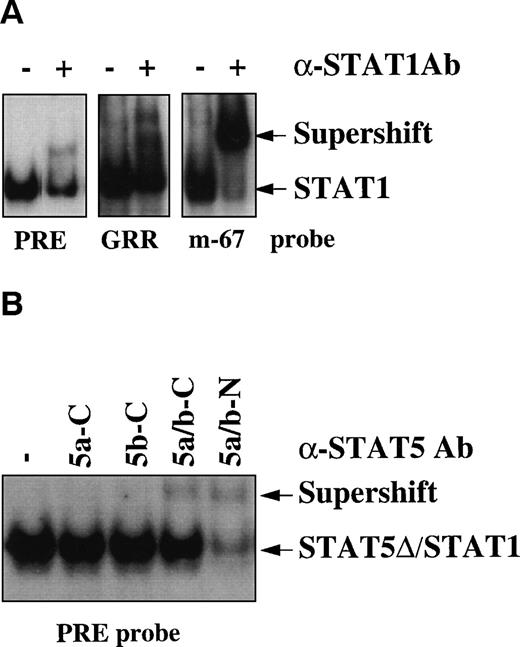

To determine which protein(s) of the STAT family was responsible for the binding activity observed in infected individuals, supershift experiments were performed by using specific Abs raised against several STAT proteins from STAT1 to STAT6. Partial and complete supershifting of the DNA binding complex was observed using the PRE and the GRR oligonucleotides or the hSIE/m-67 oligonucleotide, respectively, by anti-STAT1 Abs, which recognize the last C-terminal aa (Fig 2A). To characterize the nature of the residual DNA binding activity observed with the PRE oligo, we tested Abs recognizing specifically the other STATs capable of binding the STAT binding elements (from STAT3 to STAT6). In contrast to anti-STAT3, anti-STAT4, and anti-STAT6 Abs (data not shown), the N-terminal, but not the C-terminal anti-STAT5 Ab almost completely eliminated the PRE/STAT binding complex (Fig 2B). These results indicate that both full-length (fl)-STAT1 and a C-terminal truncated isoform of STAT5 (STAT5-Δ) are constitutively activated in HIV+individuals.

STAT1 and STAT5-▵ are constitutively activated in HIV+ patients. (A) Supershift analysis using the extract of patient no. 4 of Fig 1, anti-STAT1 rabbit polyclonal Ab, and the different oligonucleotides PRE, GRR, and hSIE/m-67. (B) Supershift analysis using the PRE oligo and 4 different rabbit polyclonal Abs raised against C- (C) or N-terminal (N) epitopes of STAT5a/b proteins.

STAT1 and STAT5-▵ are constitutively activated in HIV+ patients. (A) Supershift analysis using the extract of patient no. 4 of Fig 1, anti-STAT1 rabbit polyclonal Ab, and the different oligonucleotides PRE, GRR, and hSIE/m-67. (B) Supershift analysis using the PRE oligo and 4 different rabbit polyclonal Abs raised against C- (C) or N-terminal (N) epitopes of STAT5a/b proteins.

STAT5a/b expression in HIV-infected patients.

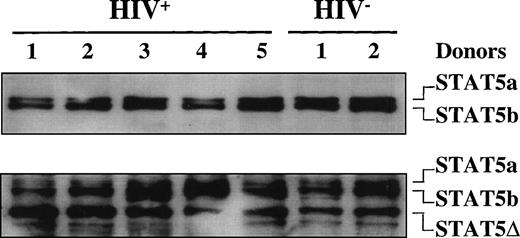

Because supershift analysis on EMSA showed the presence of C-terminal truncated STAT5 in the DNA-protein complex, in addition to fl-STAT1α, we further investigated the presence of truncated STAT5 isoforms in both HIV+ and HIV− individuals. Unexpectedly, immunoblot analyses of WCEs obtained from 5 HIV+ patients and 2 uninfected donors using a mixture of anti-STAT5a and anti-STAT5b Abs demonstrated that both STAT5a and STAT5b fl proteins (96 and 94 kD, respectively) were expressed in both controls and HIV+ patients (Fig3). When the same filter was stripped and rehybridized with an anti-STAT5 Ab recognizing an internal epitope of STAT5, a truncated isoform of approximately 80 kD in size, in addition to the fl-STAT5a/b proteins, was clearly detectable both in HIV-seronegative and -seropositive individuals (Fig 3).

STAT5 expression in HIV-infected patients. Immunoblotting of WCEs (10 μg) of PBMCs isolated from 4 HIV-infected and 2 healthy, HIV− individuals using a mixture of anti-STAT5a and anti-STAT5b rabbit polyclonal Abs in the upper panel and, after stripping of the filter, using an anti-STAT5 mouse MoAb that recognizes an internal epitope of STAT5 (lower panel).

STAT5 expression in HIV-infected patients. Immunoblotting of WCEs (10 μg) of PBMCs isolated from 4 HIV-infected and 2 healthy, HIV− individuals using a mixture of anti-STAT5a and anti-STAT5b rabbit polyclonal Abs in the upper panel and, after stripping of the filter, using an anti-STAT5 mouse MoAb that recognizes an internal epitope of STAT5 (lower panel).

Thus, the immunoblot analysis confirmed the existence of a truncated STAT5 isoform also in PBMCs of uninfected healthy individuals. These results are in partial disagreement with a recent report by Pericle et al11 indicating a downmodulated expression of STAT5a/b in T lymphocytes of HIV-infected individuals.

STAT-DNA binding activity in PBMC subsets.

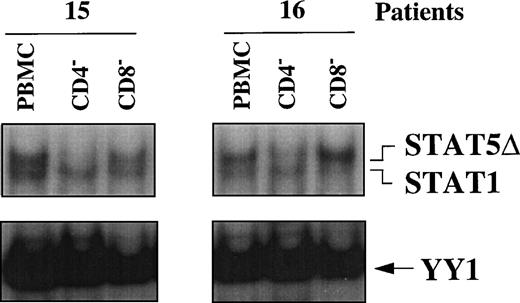

To assess whether STAT5Δ and STAT1 were differentially activated in PBMC subsets of HIV-seropositive individuals, WCEs of CD4+- and CD8+-depleted PBMCs were compared with WCEs of unfractionated PBMCs obtained from 2 HIV-infected individuals (no. 15 and 16) by EMSA (Fig 4). In WCEs of both patients, STAT5Δ and STAT1 migrated as 2 independent bands, with the upper band corresponding to STAT5Δ and the lower band to STAT1, as confirmed by supershift analysis (data not shown). It is noteworthy that depletion of CD4+ cells, but not of CD8+, resulted in the disappearance of the upper band (STAT5Δ) compared with unfractionated PBMCs, indicating that activation of STAT5Δ occurred selectively in CD4+ cells. In contrast, STAT1-DNA binding activity remained unchanged compared with the whole PBMCs after depletion of either CD4+ or CD8+ cells (Fig 4).

STAT activation in PBMC subsets of 2 HIV-infected patients. EMSA using WCEs (15 μg) obtained from PBMCs, CD4+- and CD8+-depleted PBMCs, and a mixture of PRE and UCR radiolabeled oligonucleotides.

STAT activation in PBMC subsets of 2 HIV-infected patients. EMSA using WCEs (15 μg) obtained from PBMCs, CD4+- and CD8+-depleted PBMCs, and a mixture of PRE and UCR radiolabeled oligonucleotides.

Expression of STAT5a and STAT5b in PHA blasts infected in vitro with 6 different HIV-1 strains.

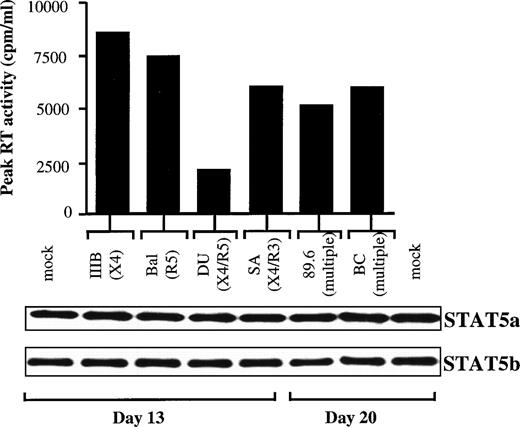

We next assessed whether STAT5 downmodulation occurred during acute infection in vitro, as reported in activated PBMCs infected with the dual-tropic strain HIV1BZ167 strain.11 To this end, 6 HIV-1 isolates, characterized by different cellular tropisms and coreceptor usage, were used to infect PHA blasts obtained from normal donors. Kinetics of infection were observed up to at least 20 days. As shown in Fig 5, the viruses were divided in 2 groups according to the day of peak RT activities. All of the infections were productive, as demonstrated by the comparable levels of the peak RT activities (Fig 5). In parallel, we analyzed WCEs obtained from the PBMCs at the peaks of infection by immunoblotting experiments using specific anti-STAT5a and anti-STATb Abs. No evidence of downregulation of either STAT5a or STAT5b protein expression was observed after in vitro HIV infection with these different viruses. In addition, we found no difference in the expression of STAT5-Δ between mock-infected and HIV-infected cells (data not shown), as previously observed by comparing WCEs obtained from HIV+ and HIV− individuals by using an anti-STAT5 Ab raised against an internal epitope of STAT5.

Expression of STAT5a and STAT5b in PHA blasts infected in vitro with 6 different HIV-1 viral strains. (Upper panel) Peak of RT values of kinetics of infection, observed up to 20 days, of PBMCs purified from a normal healthy donor and then infected in vitro with comparable moi of either 3 laboratory-adapted HIV-1 strains (IIIB/LAI, BaL, and 89.6) or 3 primary isolates (DU, SA, and BC). The peak of RT values was at day 13 for the IIIB, BaL, DU, and SA strains and at day 20 for the 89.6 and BC strains. (Lower panel) Immunoblotting of WCEs obtained at the indicated peaks of blast infection using first anti-STAT5a and then, after stripping of the filter, anti-STAT5b rabbit polyclonal Abs.

Expression of STAT5a and STAT5b in PHA blasts infected in vitro with 6 different HIV-1 viral strains. (Upper panel) Peak of RT values of kinetics of infection, observed up to 20 days, of PBMCs purified from a normal healthy donor and then infected in vitro with comparable moi of either 3 laboratory-adapted HIV-1 strains (IIIB/LAI, BaL, and 89.6) or 3 primary isolates (DU, SA, and BC). The peak of RT values was at day 13 for the IIIB, BaL, DU, and SA strains and at day 20 for the 89.6 and BC strains. (Lower panel) Immunoblotting of WCEs obtained at the indicated peaks of blast infection using first anti-STAT5a and then, after stripping of the filter, anti-STAT5b rabbit polyclonal Abs.

HIV upregulates STAT activation in vitro.

To investigate whether HIV infection could lead to STAT activation, we analyzed WCEs of resting cells exposed to HIV-1IIIB/LAI and HIV-1BaL strains at 0.1 moi by EMSA (Fig 6). Infection of PHA blasts, although more efficient than that of resting cells, was not informative, because mock-infected cells showed a very strong basal level of STAT activation due to PHA and IL-2 stimulatory effects (data not shown). Therefore, we analyzed resting PBMCs, NA-PBMCs, and MΦ isolated from a healthy normal donor cultured for 7 days in standard medium not containing mitogens such as PHA or IL-2. Mock-infected PBMCs and NA-PBMCs showed a basal level of STAT activation likely as a result of cytokine expression during the 7 days of culture. In support of this hypothesis, WCEs produced from mock-infected cells harvested after 1 and 4 days of culture did not show evidence of STAT activation (data not shown). However, in WCEs from either IIIB- or BaL-infected cells, STAT activation was clearly enhanced over the basal level of uninfected WCEs (Fig 6). It is noteworthy that WCEs prepared from either uninfected or infected MΦ did not show STAT activation. Thus, in vitro STAT activation seems to occur after infection of resting T cells, but not of MΦ.

STAT activation in resting PBMCs exposed in vitro to HIV-1. EMSA using WCEs (8 μg) obtained from resting PBMCs, NA-PBMCs, and M▹ exposed for 7 days to HIV-1IIIB/LAI and HIV-1BaL strains (0.1 moi) and a mixture of PRE and UCR radiolabeled oligonucleotides. After a single round of purification, CD4+-depleted PBMCs of patients no. 15 and 16 contained 3% and 1% CD4+ cells, respectively, whereas CD8+-depleted PBMCs contained 0.3% and 1% CD8+ cells, respectively.

STAT activation in resting PBMCs exposed in vitro to HIV-1. EMSA using WCEs (8 μg) obtained from resting PBMCs, NA-PBMCs, and M▹ exposed for 7 days to HIV-1IIIB/LAI and HIV-1BaL strains (0.1 moi) and a mixture of PRE and UCR radiolabeled oligonucleotides. After a single round of purification, CD4+-depleted PBMCs of patients no. 15 and 16 contained 3% and 1% CD4+ cells, respectively, whereas CD8+-depleted PBMCs contained 0.3% and 1% CD8+ cells, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we report for the first time that a constitutive activation of STAT proteins occurs in the majority of HIV-infected individuals (75%; Table 1), in contrast to healthy seronegative controls. This activity was accounted for by activation of both STAT1α and, mostly, of a truncated STAT5 isoform; the latter was comparably expressed, as inactive protein, in PBMCs of both HIV-infected and uninfected individuals. No evidence of diminished STAT5 expression was observed either from infected individuals or after in vitro infection of PHA blasts by a panel of HIV strains differing for chemokine coreceptor usage. However, activation of STAT was observed in resting PBMCs and NA-PBMCs infected in vitro with HIV-1IIIB/LAI or HIV-1BaL.

In agreement with our findings, it has been previously shown that STATs are constitutively activated after viral (HTLV-I) or oncogenic (v-Abl, raf/myc, abl/myc, and v-src) transformation.4 In the case of HIV-infected individuals, we have shown here that the STAT proteins activated in vivo and in vitro were STAT1α and STAT5-Δ. In vivo, STAT1α and STAT5-Δ activation unlikely represents the consequence of HIV infection per se in that only a minority of PBMCs (1:100 to 1:1,000) are actually infected in vivo,20 although we observed enhancement of STAT activation in resting T cells infected in vitro after 7 days of culture. Given that STAT binding to the DNA requires JAK-dependent phosphorylation of 1 or more tyrosine residues,4 5 dysregulated expression of specific cytokines or some other factors, resulting in a constitutive JAK activation, is likely the key event underlying STAT activation in HIV-infected individuals. Unfortunately, we could not further investigate the enzymatic activity of JAKs in HIV-seropositive individuals by immunoprecipitation as a consequence of the limited material allowing us to perform exclusively immunoblotting analyses and because of the lack of commercially available Abs specific for phosphorylated JAKs.

The nature of the possible cytokine(s) or factor(s) that might constitutively trigger JAK activation and, consequently, activation of STAT1α and STAT5-Δ will require further studies. In this regard, STAT1 and STAT5 are activated by both IFNα and IFNγ as well as by several cytokines, such as IL-2, IL-3, IL-5, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, several hormones, and growth factors such as growth hormone, prolactin, erythropoietin, and thrombo- poietin.4 In particular, IFNα, IFNγ, and IL-2 are critical cytokines for several functions of the immune system,21-23 which are profoundly dysregulated by HIV infection.6 In par- ticular, Abs against IFNα were shown to revert the immunosuppressed state of HIV-infected PBMC cultures.24 However, IFNα-dependent STAT5 activation in human T lymphocytes,25 in contrast to other cell types and several cell lines,26-28 has not been demonstrated so far. High levels of IFNγ and/or its related molecule neopterin have been reported in the plasma/serum of HIV-infected individuals,29,30 whereas its expression in the germinal centers (GC) of the lymph nodes by infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes is a peculiar feature of HIV infection.31Conflicting results regard IL-2 expression in HIV-infected individuals32 in that the defective IL-2 secretion, which was first described as one of the hallmarks of AIDS,33 was not observed in a per cell-based analysis.34 Furthermore, an increased level of IL-2 in the cerebrospinal fluid35 and in the GC of the lymph nodes of AIDS patients31 has also been shown. IL-2 plays a critical role in the activation of lymphocytes,21,22 whereas its role on STAT5 activation in lymphocyte proliferation is still controversial.36-38

At present, it remains unclear why STAT5-Δ is preferentially activated in CD4+ cells of HIV-infected individuals, whereas such restriction is not observed for STAT1 activation. As discussed previously, direct infection and replication of HIV-1 in vivo could only minimally account for this phenomenon. However, amplification loops leading to cytokine dysregulation and/or anergy and apoptosis of CD4+ T cells have been associated with improper signaling caused by shed gp120 Env either alone or complexed with Abs or complement components.1,6 39

We have also observed that STAT5-Δ is expressed in PBMC-seronegative, healthy individuals. In this regard, Lokuta et al40observed that a smaller isoform of STAT5, identical in size to the STAT5-Δ described in the present study, was preferentially expressed in immature macrophages among 3 murine macrophage cell lines at different stages of maturation and in primary cells. In contrast, we did not observe STAT5-Δ and STAT1 activation in either unexposed or HIV-1–exposed unstimulated MΦ. Although the ultimate function of this truncated STAT5 isoform(s) is unknown at present, several studies have demonstrated that truncated STAT5 isoforms can exhibit a higher DNA binding affinity compared with fl-STAT5.41-44Furthermore, we44 and others41-43 have previously demonstrated that activated C-terminal truncated STAT5 might exert a dominant negative effect in a variety of experimental systems, including murine erythroid progenitor and early hematopoietic cells. These findings suggest that activated STAT5-Δ may possess similar characteristics in HIV-infected patients' PBMCs, potentially playing a role in the reduced lymphocyte proliferation and anergy observed in these individuals.

STAT activation did not correlate with viral load, CD4+T-cell counts, or being either naive or under antiretroviral therapy, likely indicating a long-lasting perturbation of cell activation not reflective of the downregulation of in vivo HIV replication, as judged by the levels of viremia (Table 1). Whether immune based therapies, such as the combined used of IL-2 and antiretrovirals, can affect STAT activation is currently under scrutiny in our institute.

Finally, we have also shown that both HIV+ patients and in vitro-infected PHA blasts expressed normal levels of STAT5a and STAT5b, in contrast to what was recently reported by Pericle et al.11 In this regard, we have examined a larger number of HIV patients (14 v 5) than reported11; however, a different technical approach (immunoblotting in our study vimmunoprecipitation followed by immunoblotting in that of Pericle et al11) has been adopted in the analyses of STAT5 isoforms expression. It is also conceivable that the discrepancy of in vivo results of these 2 studies may depend on the fact that we examined total unfractionated PBMCs and not purified T lymphocytes. In vitro, although we could not test the highly virulent HIV-1BZ167 strain described in the study of Pericle et al,11 we have analyzed a panel of HIV isolates differing for coreceptor usage, including multitropic viruses such as 89.6 and BC, in the same experimental conditions reported. However, we failed to obtain evidence supporting a downmodulation of STAT5b upon in vitro HIV infection.

In conclusion, the STAT-binding activity found in most HIV-infected individuals may represent a new surrogate marker for monitoring both a global activation of the cytokine network as well as potentially their immunological reconstitution.

Supported by grants of the IX National Project for research against AIDS of the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS). C.B. and S.G. are fellows of the ANLAIDS and ISS, Italy, respectively.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Chiara Bovolenta, PhD, P2/P3 Laboratories, San Raffaele Scientific Institute, via Olgettina n. 58, 20132 Milano, Italy; e-mail: bovolenta.chiara@hsr.it.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal