To the Editor:

A 48-year-old male patient with a previous history of 4 primary melanomas was admitted 1 year after the last melanoma excision because of recent onset of fatigue, weakness, weight loss, shortness of breath, and limb pain. The initial hematological laboratory evaluation disclosed moderate anemia, thrombocytopenia, and a marked leukocytosis of 22.5 × 103 cells/μL, with 28% atypical plasmacytoid cells, and acute leukemia was suspected. Repeated Wright-Giemsa stains of peripheral blood smear confirmed the presence of 30% to 40% abnormal, large pleomorphic cells, with abundant cytoplasm, eccentric nuclei, and marked anisokaryosis (Fig 1A). These cells were negative for myeloid-, T-, B-, and natural killer (NK)-cell markers. Surprisingly, they were identified as circulating amelanotic melanoma cells by their reactivity with S100 protein-, vimentin-, and melanoma-specific HMB-45 monoclonal antibodies. Serum levels of the melanoma tumor markers S100 and MIA protein were markedly elevated, whereas polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for tyrosinase mRNA was negative. Bone marrow biopsy showed an almost complete replacement of hematopoiesis by HMB-45–positive melanoma cells. Chest x-ray and abdominal ultrasound showed no further evidence of macroscopic disease. The condition of the patient rapidly deteriorated and, despite supportive measures, he died on the ninth hospital day. Postmortem examination showed the presence of HMB-45–positive tumor cell aggregates trapped in the microcirculation of the liver (Fig 1B), the lungs, the kidneys, and the heart, with concomitant diffuse infiltrates in the perivascular space. The spleen also showed diffuse infiltration by tumor cells. The immediate cause of death was plugging of the pulmonary vasculature resulting in congestive right heart failure.

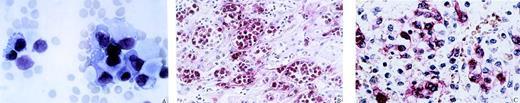

Circulating amelanotic melanoma cells. (A) Wright-Giemsa stain of peripheral blood smear shows large pleomorphic cells with abundant cytoplasm, eccentric nuclei, and marked anisokaryosis. (B) Paraffin-embedded liver tissue was stained with melanomaspecific HMB-45 monoclonal antibody. Numerous melanoma cells are found in hepatic sinusoids and hepatic veins without significant extravasation. (C) Bone marrow biopsy stained with HMB-45 illustrates the significant reduction of hematopoiesis and the dense infiltration by melanoma cells.

Circulating amelanotic melanoma cells. (A) Wright-Giemsa stain of peripheral blood smear shows large pleomorphic cells with abundant cytoplasm, eccentric nuclei, and marked anisokaryosis. (B) Paraffin-embedded liver tissue was stained with melanomaspecific HMB-45 monoclonal antibody. Numerous melanoma cells are found in hepatic sinusoids and hepatic veins without significant extravasation. (C) Bone marrow biopsy stained with HMB-45 illustrates the significant reduction of hematopoiesis and the dense infiltration by melanoma cells.

Bone marrow infiltration of human melanoma is found in up to 7% of in vivo staging procedures and in up to 45% of autopsy cases.1 So far, it has rarely been reported that this would result in significant numbers of circulating melanoma cells in peripheral blood.2 Usually, circulating melanoma cells can only be detected on the submicroscopic level by methods such as PCR for tyrosinase melanoma associated antigen.3 It is not clear whether the massive load of tumor cells observed in the peripheral blood is caused by dissemination of melanoma cells from bone marrow infiltration (Fig 1C) or whether the melanoma cells proliferated autochthonously in the peripheral blood compartment. Although the first possibility seemed to be more likely, we attempted to mimic the in vivo situation by culturing whole blood cells or Ficoll gradient-enriched mononuclear cells containing the tumor cells from this patient. Even by using different growth media, the tumor cells did not grow in suspension. However, when the cells were allowed to adhere to plastic of culture flasks, a stable cell line could be established that is now in culture for more than 1 year. This is the first report of a melanoma cell line established from the peripheral blood of a patient. To analyze the apparent reduced ability to transmigrate and to form solid metastasis, we examined immunocytologically early passage melanoma cells from the cell line for molecules relevant for adhesion and migration. We found positive staining for integrin subunits α1 through 6 and β1 as well as intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and metastasis-promoting CD44 variant isoforms v5 and v6. There was no E-cadherin expression. Thus, the cells display a pheno- type that is thought to be very compatible with progression of melanoma and other solid tumors by increasing proliferation, invasion, and/or metastasis.4 5

It has been calculated in an animal model of melanoma that 80% of cells entering the microcirculation survive and extravasate by 24 hours.6 Because this patient had a calculated number of 5 × 1010 circulating melanoma cells without macroscopically detectable metastases, it can be concluded that extravasation was significantly reduced, which therefore represents a key stage of metastatic control in this case. Alternatively, death of the patient might have occurred before solid metastases developed. Cancer cells of nonhematologic origin are only rarely seen on routinely prepared blood smears. The term carcinocythemia had been introduced to describe rare cases of disseminating carcinoma mimicking the clinical picture of acute leukemia.2,7 8 We suggest describing the phenomenon in the presented case as melanocythemia.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal