Abstract

Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (SD), an inherited disorder with varying cytopenias and a marked tendency for malignant myeloid transformation, is an important model for understanding genetic determinants in hematopoiesis. To define the basis for the faulty hematopoietic function, 13 patients with SD (2 of whom had myelodysplasia with a clonal cytogenetic abnormality) and 11 healthy marrow donors were studied. Patients with SD had significantly lower numbers of CD34+ cells on bone marrow aspirates. SD CD34+ cells plated directly in standard clonogenic assays showed markedly impaired colony production potential, underscoring an intrinsically aberrant progenitor population. To assess marrow stromal function, long-term marrow stromal cell cultures (LTCs) were established. Normal marrow CD34+ cells were plated over either SD stroma (N/SD) or normal stroma (N/N); SD CD34+cells were plated over either SD stroma (SD/SD) or normal stroma (SD/N). Nonadherent cells harvested weekly from N/SD LTCs were strikingly reduced compared with N/N LTCs; numbers of granulocyte-monocyte colony-forming units (CFU-GM) derived from N/SD nonadherent cells were also lower. SD/N showed improved production of nonadherent cells and CFU-GM colonies compared with SD/SD, but much less than N/N. Stem-cell and stromal properties from the 2 patients with SD and myelodysplasia did not differ discernibly from SD patients without myelodysplasia. We conclude that in addition to a stem-cell defect, patients with SD have also a serious, generalized marrow dysfunction with an abnormal bone marrow stroma in terms of its ability to support and maintain hematopoiesis. This dual defect exists in SD with and without myelodysplasia.

SHWACHMAN-DIAMOND SYNDROME (SD) is a multisystem autosomal-recessive disorder characterized by exocrine pancreatic dysfunction, bony metaphyseal dysostosis, and varying degrees of marrow dysfunction with cytopenias.1-3 In addition, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) have been recognized as major complications in this disease and occur in up to one third of patients.2 3 The genetic defect and molecular basis for SD that predispose patients to bone marrow failure and malignant myeloid transformation are not known.

Reduced numbers of bone marrow progenitors, eg, granulocyte-monocyte colony-forming units (CFU-GM) and erythrocyte burst-forming units (BFU-E) have been demonstrated in most patients, compatible with a defective stem-cell origin for the marrow failure in SD.4-6In these published studies from about 25 years ago, the proliferative capacity and frequency of committed myeloid progenitors varied widely, as did peripheral blood cell counts. Production of “colony-stimulating activity” from patients’ peripheral leukocytes appeared normal when tested on normal marrow progenitors.4 Since these original observations were published, understanding of the hematopoietic defects in this disorder has not progressed further.

The bone marrow microenvironment has a central role in supporting, maintaining, and regulating hematopoiesis by providing compartmentalization and production of soluble regulatory messages in “stem-cell niches” to which CD34+ cells are anchored.7,8 A defective microenvironment as assessed by long-term bone marrow cultures (LTCs) has been suggested as a cause for certain cases of acquired aplastic anemia9,10 and for adult patients with MDS.11

Marrow stomal function has never been studied in SD. Since this disorder is an inherited bone marrow failure syndrome with a wide range of hematologic abnormalities, it is clearly an important model for understanding genetic determinants in hematopoiesis and in developmental biology. Further, the link between SD and MDS/AML underscores an important association between heredity and leukemogenesis. For these reasons, we characterized progenitor cell/marrow stromal cell function in SD to define the basis for the flawed hematopoiesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient population and clinical diagnosis.

Patients were included if they fulfilled the diagnostic criteria from our institution.12 Accordingly, 13 patients were included in this study, conducted from February 1997 to February 1998 inclusively. Clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. No patient was transfusion-dependent. One patient (no. 13) received treatment with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) because of severe neutropenia and infection. No patient had been previously diagnosed with MDS or AML; however, during the study, MDS was unmasked in 2 patients (no. 1 and no. 2, Table 1). Both had marrow cytogenetic abnormalities of clonal i(7q); one of them also had clonal del(20q) and dysplastic changes of the myeloid series. Clinical aspects of these 2 patients have been previously reported.13 14

Clinical Characteristics of Patients With SD

| UPN . | Age* (y) . | Sex . | Metaphyseal Dysostosis . | Short Stature, <3 Percentile . | Blood Counts . | HbF . | Bone Marrow Morphology . | Cytogenetics . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell . | G . | E . | Meg . | Blasts . | ||||||||

| 1 | 7 | M | No | Yes | N, A, T | 9.7 | ⇓ | ⇓ | n | ⇓ | <5% | 46XY,i(7q)[17] |

| 2 | 5 | M | No | Yes | N, A | 9.4 | ⇓ | d, l | n | n | 5% | 46XY,del(20q)[11]/46XY,i(7q)[2]/46XY[7] |

| 3 | 14 | M | Mild | Yes | N | <1 | ⇓ | ⇓ | n | ⇓ | <5% | 46XY |

| 4 | 16 | F | Mild | No | N, T | 1.1 | ⇓ | ⇓ | n | ⇓ | <5% | 46XX |

| 5 | 13 | F | Severe | Yes | N, A | 3.1 | ⇓ | l | d | n | <5% | 46XX |

| 6 | 2 | M | No | No | N, A | 3.6 | ud | ⇓d, l | n | n | 5% | 46XY |

| 7 | 14 | F | ud | Yes | N, A, T | 1.7 | ⇓ | ⇓ | n | ⇓ | <5% | 46XX |

| 8 | 18 | M | Severe | Yes | N, A, T | 2.0 | ⇓ | ⇓ | n | ⇓ | <5% | 46XY |

| 9 | 6 | F | Moderate | Yes | N, A | 4.9 | ⇓ | n | n | ⇓ | <5% | 46XX |

| 10 | 1 | F | ud | Yes | N, A, T | 9.6 | ud | n | n | ud | <5% | 46XX |

| 11 | 8 | M | Moderate | Yes | N, T | 1.4 | ⇓ | ⇓ | n | n | <5% | 46XY |

| 12 | 2 | F | No | No | N | 2.8 | n | ⇓ | n | n | <5% | 46XX |

| 13 | 5 | M | No | Yes | N, A, T | ud | ⇓ | ⇓ | n | ⇓ | <5% | 46XY |

| UPN . | Age* (y) . | Sex . | Metaphyseal Dysostosis . | Short Stature, <3 Percentile . | Blood Counts . | HbF . | Bone Marrow Morphology . | Cytogenetics . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell . | G . | E . | Meg . | Blasts . | ||||||||

| 1 | 7 | M | No | Yes | N, A, T | 9.7 | ⇓ | ⇓ | n | ⇓ | <5% | 46XY,i(7q)[17] |

| 2 | 5 | M | No | Yes | N, A | 9.4 | ⇓ | d, l | n | n | 5% | 46XY,del(20q)[11]/46XY,i(7q)[2]/46XY[7] |

| 3 | 14 | M | Mild | Yes | N | <1 | ⇓ | ⇓ | n | ⇓ | <5% | 46XY |

| 4 | 16 | F | Mild | No | N, T | 1.1 | ⇓ | ⇓ | n | ⇓ | <5% | 46XX |

| 5 | 13 | F | Severe | Yes | N, A | 3.1 | ⇓ | l | d | n | <5% | 46XX |

| 6 | 2 | M | No | No | N, A | 3.6 | ud | ⇓d, l | n | n | 5% | 46XY |

| 7 | 14 | F | ud | Yes | N, A, T | 1.7 | ⇓ | ⇓ | n | ⇓ | <5% | 46XX |

| 8 | 18 | M | Severe | Yes | N, A, T | 2.0 | ⇓ | ⇓ | n | ⇓ | <5% | 46XY |

| 9 | 6 | F | Moderate | Yes | N, A | 4.9 | ⇓ | n | n | ⇓ | <5% | 46XX |

| 10 | 1 | F | ud | Yes | N, A, T | 9.6 | ud | n | n | ud | <5% | 46XX |

| 11 | 8 | M | Moderate | Yes | N, T | 1.4 | ⇓ | ⇓ | n | n | <5% | 46XY |

| 12 | 2 | F | No | No | N | 2.8 | n | ⇓ | n | n | <5% | 46XX |

| 13 | 5 | M | No | Yes | N, A, T | ud | ⇓ | ⇓ | n | ⇓ | <5% | 46XY |

Abbreviations: UPN, unique patient number; Abnorm, abnormalities; HbF, fetal hemoglobin; Cell, cellularity; G, granulocyte count; E, erythrocyte count; Meg, megakaryocyte count; N, neutropenia (neutrophil concentration <1.5 × 109/L); A, anemia (hemoglobin concentration <2 SD adjusted for age35); T, thrombocytopenia (platelet count <150 × 109/L); ⇓, decreased; n, normal; l, left shift; ud, undetermined; d, dysplastic; un, unknown.

Age at the time of study.

Consent was obtained from the patients or their parents for the study. Bone marrow samples were also obtained from hematologically healthy donors during the harvest for bone marrow transplant. Informed, written consent was obtained in all cases.

Bone marrow samples.

Patients underwent bone marrow aspiration and biopsy under conscious sedation with intravenous propafol and local infiltration with lidocaine. Bone marrow aspirates were collected from the posterior superior iliac crest into α-medium containing 10 U of preservative-free heparin per milliliter, layered over percoll, and centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 10 minutes. Light-density mononuclear cells were collected and washed twice in Iscove’s medium. Mononuclear cells were either plated directly for LTC or underwent CD34+ fractionation and were cryopreserved.

CD34+ cell fractionation.

CD34+ cells were separated by the Mini-MACS immunomagnetic separation system (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) as previously described15 with few modifications. Post-percoll mononuclear cells were washed in cold buffer containing phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.5% bovine serum albumin, treated with biotinylated anti-CD34 antibodies, and incubated on ice for 15 minutes. Cells were then washed, treated with Streptavidin Microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec), incubated for 15 minutes, washed again, and applied to a magnetic column. Columns were then removed from the magnetic fields and the CD34+ cells eluted with a plunger. To reach a purification of approximately 98%, cells were passed through a second magnetic column. The collected cells were then cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen until used.

Percentage of CD34+ cells in marrow cell samples.

Freshly obtained 3-mL aliquots of bone marrow aspirates were layered over Ficoll and centrifuged at 1,600 rpm for 25 minutes. Light-density cell layer was collected and washed in PBS/bovine serum albumin 0.5%. Cells (1 × 105) were incubated with either fluorescein-isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD34+antibody or IgG1-FITC isotype control (both from Immunex, Seattle, WA), and then resuspended in PBS with paraformaldehyde 0.5%; cells were immediately analyzed by a Coulter Epics XL-MCL flow cytometer (Coulter, Hialeah, FL). A minimum of 12,000 events was collected. Events that fell outside the negative staining regions identified by the isotype control sample were considered CD34+ cells.

Standard short-term colony assays from CD34+cells.

Standard short-term colony assays of CD34+ cells were performed as previously described15 with few modifications. CD34+ cells were plated in duplicate at a cell density of 1.8 × 103 cells per 0.6 mL well (of a 24-well plate) in 0.8% methylcellulose (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland), 20% normal human plasma, 10–5 mol/L 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma, St Louis, MO), 40 U/mL interleukin-3 (Immunex), 10 ng/mL G-CSF (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA), 50 ng/mL mast cell growth factor (Immunex), and 2 U/mL erythropoietin (Ortho Biologics, Manati, PR). Cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere (5% CO2 and air). Colonies of 50 cells or more were scored after 14 days under an inverted microscope as CFU-GM, BFU-E, or mixed colony-forming units (CFU-mix).

For megakaryocyte CFU (CFU-Meg) colony assays, 0.2 × 105 CD34+ cells were placed in 0.2-mL duplicate cultures (in a 24-well plate) containing 0.8% methylcellulose, 20% normal human plasma, 50 ng/mL mast cell growth factor (Immunex), and 50 ng/mL megakaryocyte growth and development factor (Amgen). Colonies of at least 3 mature megakaryocytes were scored after 14 days.

Long-term cell cultures.

Stromal layers from 10 patients and 11 normal subjects were established as previously described16 by plating 2 × 106 post-percoll bone marrow mononuclear cells in 2 mL LTC medium (Myelocult; Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada), containing α-medium with 12.5% fetal calf serum, 12.5% horse serum, 0.1 mmol/L 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.016 mmol/L folic acid, 2.0 mmol/L glutamine, 0.16 mmol/L inositol, and 10–5 mol/L hydrocortisone. LTCs were placed in a humidified 37°C incubator with a maintained atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air for 3 to 5 days, then transferred to a 33°C incubator with the same atmosphere. Stromal layers were grown for 4 to 5 weeks, with weekly feeding using one-half medium replacement.

Support of hematopoiesis was then assessed by crossover experiments performed by plating 2 × 105 patient or control CD34+ cells over patient or control LTCs after irradiation (15 Gy) of the stroma. Four combinations of experiments were performed: normal CD34+ cells on normal stroma (N/N, n = 11); normal CD34+ cells on SD stroma (N/SD, n = 10); SD CD34+ cells on normal stroma (SD/N, n = 4); and SD CD34+ cells on SD stroma (SD/SD, n = 4). Five of the 11 sets of control experiments (N/N) were allogeneic combinations, whereby normal CD34+ cells from 1 donor source were plated over a control stromal layer from a different donor. Similarly, 2 of the 4 SD/SD experiments were allogeneic combinations in which patient CD34+ cells were plated on a different patient’s stromal layer. All other control and patient combinations were autologous.

For morphologic evaluation of LTC, 10-week-old LTCs were trypsinized and prepared in paraffin blocks for histochemical stains for endothelial cells (von Willebrand’s factor), monocytic elements (CD68), and fibroblast markers (vimentin). Fat cell clusters were counted directly under an inverted microscope and expressed as numbers of clusters per 2 × 106 marrow mononuclear cells plated initially in the LTC.

LTC nonadherent cell numbers and secondary short-term colony assays.

After CD34+ cells were layered over stromal layers, hematopoiesis was assessed weekly. Nonadherent cells (6 × 103) harvested by weekly half-medium replacement of LTCs were plated in 0.6-mL secondary short-term cultures, and assayed for CFU-GM, BFU-E, and CFU-mix colony formation as described for short-term cultures from CD34+ cells. LTC-initiating cell studies by limiting dilution analysis are very difficult from SD hypocellular bone marrows because of the paucity of hematopoietic stem cells, so we elected to measure the production of CFU-GM from the nonadherent layer.9,17 With this method we did not assess the clonogenic potential of stem cells embedded in the stromal layers; however, we did assess the ability of stroma to support hematopoiesis over 10 weeks of the experiments without the need to sacrifice the LTC after 5 weeks.9

Effect of supernatants from LTCs of normal controls and patients on clonogenic assays of normal CD34+ cells.

Stromal layers from 2 controls and 2 SD patients were established as described. However, after stromal irradiation, CD34+ cells were not plated over the stromal layers. Instead, on days 1, 7, and 14 after irradiation, supernatant was replaced with fresh medium. The supernatant collected on day 14 after irradiation was stored at −80°C until tested.

Control CD34+ samples (n = 2) were plated (3 × 103 cells/mL) in duplicate cultures containing 0.8% methylcellulose (Fluka), 30% fetal calf serum, 10−5 mol/L 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), 40 U/mL interleukin-3 (Immunex), 10 ng/mL G-CSF (Amgen), 50 ng/mL mast cell growth factor (Immunex), and 2 U/mL erythropoietin (Ortho Biologics), and varied concentrations (0%, 7.5%, and 15%) of filtered-thawed LTC-supernatant from controls or patients. Cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere (5% CO2 and air). CFU-GM colonies containing 50 cells or more were scored after 14 days under an inverted microscope.

Statistics.

Using mean numbers of nonadherent cells harvested weekly from the LTCs, colony numbers in short-term cultures, and marrow CD34+cells, Student’s t test was used to determine significance of differences between patients and controls. P values less than .05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Percentage of CD34+ cells in marrow cell samples.

The percentage of CD34+ cells in marrow from 8 SD patients (mean ± SEM, 1.8% ± 0.5%) was significantly lower (P < .01) than the percentage from 10 normal controls (4.4% ± 0.5%). Ages of patients (mean ± SEM, 13 ± 2 years) and controls (13 ± 4 years) were comparable (P = .97).

Short-term colony assays from CD34+ cells.

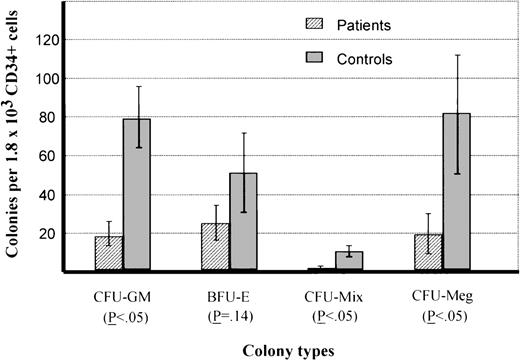

Results of clonogenic assays are shown in Fig1. Mean values of CFU-GM, CFU-mix, and CFU-Meg colonies were reduced compared with normal controls (P< .05). Mean BFU-E colony numbers were also reduced (26 v52), but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .14).

Numbers of colonies in duplicate short-term cultures from CD34+ cells of patients with SD or healthy controls (mean ± SEM).

Numbers of colonies in duplicate short-term cultures from CD34+ cells of patients with SD or healthy controls (mean ± SEM).

Stroma formation and morphologic evaluation.

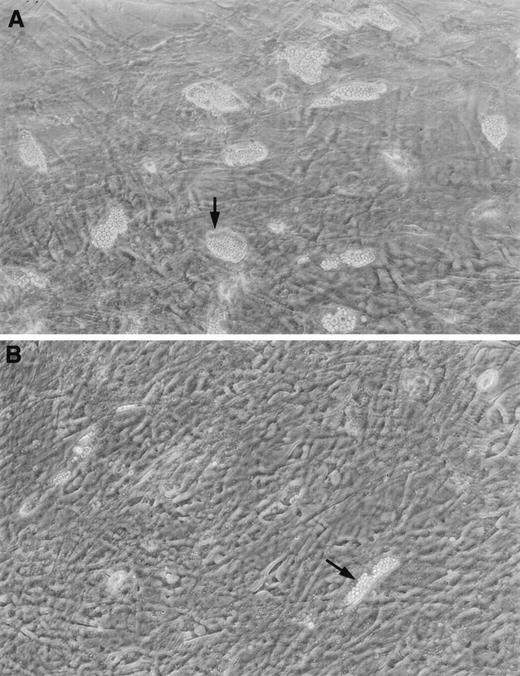

There was no difference between patients and controls in the length of time needed or ability to produce a confluent stromal layer. All patient and control samples achieved at least 75% confluent stromal layers within 4 weeks. There was also no difference between LTCs from four SD patients and from 2 controls with regard to immunostaining with von Willebrand’s factor for presence of endothelial cells, CD68 for monocytic cells, or vimentin for fibroblasts. However, fat cell cluster numbers in LTCs from 11 SD patients (mean ± SEM, 693 ± 542 per 2 × 106 marrow mononuclear cells) were significantly lower (P < .01) than for 9 controls (3,185 ± 773 per 2 × 106 marrow mononuclear cells; Fig2A and B). The only patient with relatively high numbers of fat cell clusters (6,094 per 2 × 106marrow mononuclear cells) was patient no. 13, who received G-CSF treatment for neutropenia.

Stromal layers from long-term cultures of (A) a normal control showing an abundance of clusters, and (B) a patient with SD, showing the characteristic paucity of fat cell clusters.

Stromal layers from long-term cultures of (A) a normal control showing an abundance of clusters, and (B) a patient with SD, showing the characteristic paucity of fat cell clusters.

Nonadherent cell numbers generated from LTCs and secondary short-term colony assays from the nonadherent cells.

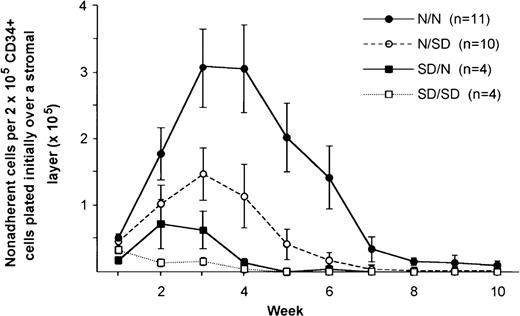

When the 4 sets of experimental combinations of CD34+ cells on stromal cells were compared, numbers of total nonadherent cells harvested from N/SD LTCs from week 2 onwards were lower than those from N/N LTCs (Fig 3). The difference was statistically significant between weeks 4 to 6 (P < .05), when LTC-initiating cells are best assessed.16 Means of CFU-GM colony numbers (Fig 4) in short-term cultures derived from nonadherent cells harvested from N/SD LTCs were lower than those from N/N LTCs, although the difference was not statistically significant (P = .07 to .08 between weeks 4 to 6).

Nonadherent cell numbers harvested weekly from long-term cultures (means ± SEM). Normal CD34+ cells from healthy controls were plated over stroma of either SD patients (N/SD) or normal donors (N/N); SD CD34+ cells were plated over either SD (SD/SD) or normal (SD/N) stroma.

Nonadherent cell numbers harvested weekly from long-term cultures (means ± SEM). Normal CD34+ cells from healthy controls were plated over stroma of either SD patients (N/SD) or normal donors (N/N); SD CD34+ cells were plated over either SD (SD/SD) or normal (SD/N) stroma.

CFU-GM numbers derived from long-term culture nonadherent cells, plated weekly in short-term clonogenic assays (means ± SEM). Normal CD34+ cells from healthy controls were plated over stroma of either SD patients (N/SD) or normal donors (N/N); SD CD34+ cells were plated over either SD (SD/SD) or normal (SD/N) stroma.

CFU-GM numbers derived from long-term culture nonadherent cells, plated weekly in short-term clonogenic assays (means ± SEM). Normal CD34+ cells from healthy controls were plated over stroma of either SD patients (N/SD) or normal donors (N/N); SD CD34+ cells were plated over either SD (SD/SD) or normal (SD/N) stroma.

Plating CD34+ cells from SD patients over stromal layers from controls augmented nonadherent numbers and colony formation, but not to the same values obtained when normal CD34+ cells were plated on normal stromas, thereby confirming a colony-producing progenitor defect in SD marrow (Figs 3 and 4). The combination of SD CD34+ cells on SD stroma showed a profoundly impaired hematopoietic interaction in which marrow function was almost totally absent (Figs 3 and 4).

No statistical differences in the nonadherent cell numbers and in the secondary CFU-GM colony numbers were observed when allogeneic and autologous control experiments (N/N) were compared, in keeping with previous reports.18 Also, plating patient CD34+cells on stromal layer from a different patient in the allogeneic SD/SD experimental combination did not correct the profoundly impaired hematopoiesis seen with the 2 autologous SD/SD combinations.

Effect of supernatants from LTCs of controls and patients on clonogenic assays of normal CD34+ cells.

Three experimental conditions were performed for controls (n = 2) and for patients (n = 2), whereby varied concentrations of supernatant from their LTCs were plated with control allogeneic CD34+ cells (n = 2) in short-term clonogenic assays. With control LTC-supernatants, there was a stepwise increment in CFU-GM colonies by adding increasing concentrations from 0% to 15% (from mean colony numbers in duplicate cultures of 83 to 124, and 138 to 182, respectively, per 3 × 103 normal CD34+ cells plated). With patient LTC-supernatants, no substantial change in the number of CFU-GM colonies was observed (from mean colony numbers of 83 to 93, and 138 to 139, respectively, per 3 × 103 normal CD34+ cells plated).

Patients with and without MDS.

By comparing colony formation in clonogenic assays of CD34+cells, no difference was noted between the 2 patients with MDS and those without; CFU-GM colony numbers were 0 and 26 per 1.8 × 103 CD34+ cells, respectively, compared with a range of 0 to 72 (mean, 24) in patients without MDS. Also, both patients with MDS had abnormal stroma, but which were indistinguishable from SD patients without MDS. For example, nonadherent cell numbers recovered at week 6 after plating 2 × 105 normal CD34+ cells on stromal layers from both SD patients with MDS were 0 and 0.16 × 105, respectively, compared with a range of 0 to 0.85 × 105 (mean, 0.16) in SD patients without MDS. Similarly, numbers of CFU-GM colonies in secondary short-term cultures derived from 6 × 103 nonadherent cells generated from the MDS patient stroma were 0 and 8, respectively, as compared with a range of 0 to 8 (mean, 1.6) from stromal studies of SD patients without MDS.

Patient no. 13 differed from the other SD patients somewhat; the marrow stromal LTC showed normal numbers of fat clusters. Also, nonadherent cell numbers recovered at week 6 after plating 2 × 105 normal CD34+ cells on this patient’s stromal layers were at the lower range of controls (0.09 × 105; controls’ mean, 1.40 × 105; range, 0.03 to 3.89 × 105). However, no CFU-GM colony growth was observed from these nonadherent cells in secondary short-term cultures (controls’ mean, 12; range, 1 to 27). Further, the CFU-GM, BFU-E, CFU-mix, and CFU-Meg colony numbers in direct short-term cultures were also low: 5, 16, 1, and 24, respectively, per 1.8 × 103 fresh CD34+ cells.

DISCUSSION

Our goal for the studies described here was to characterize the marrow dysfunction in SD. As a classic example of an inherited bone marrow failure disorder with a predisposition to MDS/AML, SD is pivotal for understanding the role of genetic factors in hematopoiesis. Once the SD gene is identified and cloned, definition of the marrow cellular abnormalities in this condition will be a prerequisite for demonstrating that transfected SD cDNA, when it becomes available, has a corrective effect on faulty hematopoiesis.

Until now, almost all information about bone marrow function in SD came from studies performed between 1979 and 1982 using light-density marrow mononuclear cells.4-6 These investigators demonstrated, in clonogenic assays, that granulocytic and erythroid progenitors were either numerically deficient in marrow or had impaired proliferative properties in most, but not all, patients. Additionally, in one study,4 there were no serum inhibitors against “CFU-C” progenitors nor against “colony-stimulating activity” when tested on control or on autologous marrow; coculture of SD patients’ peripheral blood lymphocytes with control marrow did not inhibit CFU-C colony growth either.

We used these published data as the entry point for our current study. Using contemporary technology, we have discovered new and important information about SD bone marrow dysfunction. First, we worked with a fairly homogeneous population of marrow cells, which were subfractionated into CD34+ elements. The CD34 antigen identifies cell populations that are enriched for pluripotent and lineage-restricted hematopoietic progenitors in vitro, some of which are capable of marrow reconstitution in vivo.19-21

Second, we used long-term bone marrow cultures in our study because LTC is the most physiologic in vitro system to study interactions of hematopoietic progenitors and the hematopoietic microenvironment. The microenvironment has a central role in regulating hematopoiesis because it orchestrates the interaction between adhesion-mediated cellular events and the production and compartmentalization of soluble regulatory messages.7,8 22-24 Because of this, one hypothesis at the start of the study was that the microenvironment was involved in the pathogenesis of the SD marrow disorder.

The first SD abnormality was evident on quantitation of CD34+ cells in marrows from patients with SD and in clonogenic assays of CD34+ cells. In SD marrows we found lower numbers of CD34+ cells compared with normal controls. In addition, a qualitative defect was identified: on plating freshly obtained primary samples that were subfractionated into CD34+ cells, we demonstrated reduced potential for SD samples to generate colonies of all lineages compared with controls. This finding substantiates the results obtained from 1979 to 19824-6 and underscores the intrinsically aberrant behavior of SD hematopoietic progenitors.

The second abnormal finding was a faulty marrow microenvironment. This observation, which has not been previously reported, points to a more generalized marrow disorder than was formerly suspected. In our study, we assessed stromal support of hematopoiesis by first counting the nonadherent cells that were generated weekly, and also by looking at the clonogenic potential of these nonadherent cells in short-term clonogenic assays. Differences between patients and controls were obvious. The numbers of nonadherent cells harvested from N/SD LTCs from these cells in short-term cultures were clearly lower than the numbers obtained from the N/N LTCs. The production of CFU-GM colonies from the nonadherent cells in secondary clonogenic assays proved the existence of hematopoietic progenitors in the nonadherent cell population. Although CFU-GM colony numbers from N/SD nonadherent cells were lower than those from N/N nonadherent cells, the difference was not statistically significant. This is probably because in both N/SD and N/N experimental combinations the nonadherent cells were derived from normal CD34+ cells (only the stromal layers were different), and since they were plated in equal numbers in the secondary short term cultures. As expected, SD CD34+ cells plated over normal stroma (SD/N) showed impaired generation of nonadherent cells and deficient colony formation from these cells, consistent with intrinsically flawed progenitors. SD/SD illustrated a profoundly impaired hematopoietic interaction, whereby marrow function in vitro was almost totally absent. Of note, we discerned no differences in results between SD patients without MDS and the 2 SD patients with MDS.

To determine the basis for the stromal defect, LTCs from SD patients were evaluated morphologically. The production of fat cell clusters was markedly reduced in all patients except 1 compared with that of controls. Lack of this nutrient source might be a contributing factor for the reduced ability of stroma to support hematopoiesis in vitro. However, it is difficult to reconcile this with the relatively high fat component in hypocellular bone marrow specimens from patients with SD. Alternatively, it can be merely a morphologic marker in vitro for the abnormal stroma. The latter explanation is more likely since the quantitatively normal fat cell clusters in patient no. 13 were not sufficient to improve stromal function to the level of controls. Interestingly, patient no. 13 had a relatively high number of fat cell clusters while being administered G-CSF treatment. This might be explained because G-CSF, which stimulates various cell types and early progenitors,25 26 also has a stimulatory effect on stem cells that are committed to develop into adipocytes. Compared with controls, no difference in the timeline or in ability to form a confluent stromal layer could be demonstrated. Neither were any differences noticed in the potential of bone marrow precursors to form fibroblastoid, endothelial, or monocytic components, as assessed by 3 different cellular markers.

Cytokine production by peripheral leukocytes from SD patients was shown to be adequate as measured by “colony-stimulating activity” on normal marrow progenitors,4 and no serum inhibitors of myelopoiesis could be demonstrated.4 However, this does not exclude impaired cytokine production by the bone marrow microenvironment, since paracrine production of cytokines from marrow stromal cells might be more important in hematopoietic stem-cell production. In the current study, adding supernatants from LTCs of SD patients to clonogenic assays of normal CD34+ cells did not suppress colony production, but did not augment colony growth, either. This suggests that the impaired stromal function observed is not related to inhibitory factors, but more likely, to a deficiency of one or more stroma-derived stimulatory factors. In contrast, adding supernatants from LTCs of normal subjects to clonogenic assays of normal CD34+ cells resulted in increased production of CFU-GM colonies, which is consistent with the normal, physiologic role of the marrow microenvironment in supporting hematopoiesis.

Bone marrow stroma is not only a source of hematopoietic growth factors, it also produces the adhesive matrices required for docking of hematopoietic progenitors and compartmentalization of soluble growth factors.7,8 22-24 The basis for stromal impairment in SD can be related to either reduced production of essential cytokines (eg, stem-cell factor and stromal-derived factor-1), abnormal provision of extracellular matrix (eg, collagen and glycosaminoglycans), or abnormal expression of antigens required for adhesive interactions between hematopoietic progenitors and stromal cells (eg, β1-integrins).

Although each of these components can be studied separately, we assessed SD bone marrow stroma by examining its functional capacity as an integral unit of various cell types. This represents a more physiologic in vitro assay overall. However, further studies are now necessary to identify if a specific or an individual abnormal cellular component can account for the abnormalities that we observed. The problem may involve either cells such as fibroblasts, endothelial cells, adipocytes, or mesenchymal progenitor cells, or can originate with an unknown element. As suggested by Aiuti et al,27stromal cell clones differ in their capacity to preserve CD34+/CD38−, or to allow their differentiation into CD34+/CD38+, suggesting that distinct elements of the bone marrow stroma control growth and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells and progenitors.

A stromal cell defect has been previously reported in some cases of acquired aplastic anemia.9,10 However, this is the first report of a consistent stromal defect in an inherited syndrome of bone marrow failure. Furthermore, Tennant et al11 have recently reported for the first time a stromal cell defect in adult patients with MDS. The presence of such a defect in SD may provide an important link with the preleukemic nature of this syndrome, particularly since the same abnormality was noticed in the SD patients with or without MDS. In addition, the poor outcome of patients with SD after bone marrow transplantation for severe aplastic anemia, MDS, or acute myeloblastic leukemia28-34 can be explained by the presence of such a stromal defect, which is not corrected by the bone marrow transplantation, and might be further aggravated by the conditioning regimen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank our friends and colleagues in the Severe Chronic Neutropenia International Registry for their valuable input; Rebecca Herman and Wilma Vanek for technical assistance; and Lynda Ellis, RN, Peter Durie, MD, and Richard Axtell, MD, for collaboration in patient-related matters. This report was prepared with the assistance of Editorial Services, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada.

Supported in part by grants from the Audey Stanley Memorial Leukemia Research Fund, Shwachman Syndrome Support Canada, Aplastic Anemia Association of Canada, and The Severe Chronic Neutropenia International Registry.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Yigal Dror, MD, Department of Pediatric Hematogy/Oncology, Chaim Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer 52621, Israel.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal