Abstract

Salivary gland mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type lymphomas are B-cell neoplasms that develop out of a reactive infiltrate, often associated with Sjögren's syndrome. Previous reports from our laboratory involving 10 patients suggested these lymphomas expressed a restricted immunoglobulin (Ig)VH gene repertoire with over use ofV1-69 gene segments. To better determine the frequency ofV1-69 use and whether there may also be selection for CDR3 structures, we sequenced the VH genes from 15 additional cases. Over half of the potentially functionalVH genes (8 of 14) used aVH1 family V1-69 gene segment, whereas the other cases used different gene segments from theVH1 (V1-46),VH3 (V3-7, V3-11, V3-30.3, V3-30.5), and VH4(V4-39) families. The 8 V1-69 VHgenes used 5 different D segments in various reading frames, but all used a J4 joining segment. The V1-69 CDR3s showed remarkable similarities in lengths (12-14 amino acids) and stretches of 2 to 3 amino acids between the V-D and D-J junctions. They did not resemble CDR3s typical of V1-69 chronic lymphocytic leukemias. This study extends our earlier work in establishing that salivary gland MALT lymphomas represent a highly selected B-cell population. Frequent use of V1-69 appears to differ from MALT lymphomas that develop at other sites. The high degree of CDR3 similarity among the V1-69cases suggests that different salivary gland lymphomas may bind similar, if not identical epitopes. Although the antigen specificities are presently unknown, similar characteristic CDR3 sequences are often seen with V1-69 encoded antibodies that have anti-IgG or rheumatoid factor activity.

Salivary gland mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type lymphomas are neoplasms of CD5 negative B cells that appear to arise out of a reactive infiltrate termed “lymphoepithelial (myoepithelial) sialadenitis” (LESA).1,2 LESA is seen in all patients with Sjögren's syndrome but may also be seen in salivary gland biopsy specimens from patients who do not have Sjögren's syndrome. Previous studies have suggested that direct antigen stimulation through surface immunoglobulin (Ig) molecules may be playing an important role in the development of salivary gland MALT lymphomas.3,4 For example, more than half of the different clonal LESA-associated VH genes we have sequenced from 10 different patients use a V1-69 gene segment.4,5 Because there are a total of approximately 50 different functional VH gene segments in the human genome that can potentially be used,6 these studies suggested that B cells with heavy chains encoded byV1-69 are preferentially selected for transformation in the salivary gland, presumably because of their enhanced ability to bind some, as yet unidentified, antigen relative to other B cells that are present.

Recent studies have shown that the use of V1-69 gene segments by normal B cells and other types of B-cell malignancies may also be biased or nonrandom.7 Multiple, closely related alleles ofV1-69 have been identified that can be classified as 51p1-like or 1263-like, based on several nucleotide differences in CDR2.8 Moreover, different VHgene haplotypes have been described that can contain 0, 1, or 2 copies of V1-69 genes.7 Studies using the G6 anti-idiotypic antibody, which identifies B cells expressing heavy chains encoded by 51p1-like alleles, indicated that the expression of these V1-69 genes can be proportional to the germline copy number, with 1 copy accounting for up to 4% of IgD positive normal tonsillar B cells.7 Analyses of individual peripheral blood B cells, however, found that only approximately 1.6% had productiveV1-69 rearrangements, split approximately equally between CD5 positive and CD5 negative B cells, which is close to the value expected for random use of a single copy VHgene.9 Compared with normal B-cell populations,V1-69 expression in CD5 positive B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) appears to be increased being found in 10% to 20% of cases.10-12 In addition, the expression of 51p1-like alleles appears to be strongly favored in CLL over 1263-likeV1-69 alleles.10

To better determine the frequency that V1-69 gene segments and certain alleles are utilized by salivary gland MALT lymphomas compared with normal B cells and other B-cell neoplasms, we sequenced theVH genes from an additional 15 independent cases. Besides more precisely quantitating the preferential use of 51p1-like V1-69 gene segments, this analysis also revealed that salivary gland V1-69 genes often have remarkably similar CDR3s with conserved amino acid sequence motifs at the V-D and D-J junctions. Because of the importance CDR3-encoded residues often have in determining the fine specificity of antigen binding,13 14this observation further suggests that salivary gland lymphomas from different patients may sometimes recognize the same or similar epitopes.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patient material

From a total of 18 different patients, paraffin-embedded salivary gland biopsy specimens of LESA-associated lesions that demonstrated B-cell clones using a standard polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique (see below), but had not been analyzed further forVH gene use were available from our earlier clinicopathological study.15 Histologically, 13 of the biopsy specimens met criteria considered to be diagnostic of salivary gland MALT lymphoma, 2 demonstrated LESA with halos of monocytoid cells (a borderline lesion), and 3 demonstrated only LESA. Salivary gland biopsy specimens from 2 additional patients who histologically demonstrated MALT lymphoma and had clonal B cells by PCR were also used.

Polymerase chain reaction

DNA was isolated from unstained standard thickness tissue sections as described.16 The presence of clonal B cells was confirmed by amplifying the DNA with consensus 5′VH gene framework region 3 (FW3) and 3′ JH primers for 37 cycles, electrophoresing the resultant products in 8% acrylamide gels, and staining with ethidium bromide as described.4 More complete lengthVH genes were first amplified for 37 cycles from the DNA using a variety of 5′ VHleader primers, framework region 1 (FW1) primers, or framework region 2 (FW2) primer with a consensus 3′ JH primer under standard conditions as described.4 To increase the sensitivity and obtain sufficient DNA for subsequent cloning, secondary amplification for 15 cycles using 0.5 μL of the initial reactions as a template was performed using the same conditions, only substituting an internal JH primer (JH2 for JH1) or occasionally internal FW1 primer as described.4 With the exception of a consensus FW2 primer, 5′-TGGGTCCG(C, A)CAG(G, C)C(T, C)CC(A, T)GG- 3′, which was used in 2 cases to obtain theVH genes, all the other 5′ primers were based on sequences for each of the differentVH families and have been previously published along with the 3′ JHprimers.4 5

Cloning and sequencing of polymerase chain reaction products

Isolation and purification of the clonal FW3-JHgenerated PCR products from 8% acrylamide gels was performed as described.4 Bands corresponding to more completeVH genes were isolated from 1.5% low-melt agarose gels and the DNA purified using Wizard DNA preps (Promega, Madison, WI). Approximately one third of the purified DNA was cloned using the PCR-Script kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Plasmid DNA used for sequencing reactions was obtained from overnight cultures of randomly selected bacterial colonies using Wizard mini-preps (Promega). Dideoxy sequencing in both directions was performed using Sequenase (Amersham, Cleveland, OH) with approximately one third of the plasmid DNA, according to the manufacturer's protocol. Some of the PCR products were directly sequenced as described.4 Sequence analysis was performed using MacVector software (IBI, New Haven, CT) and the VBASE database.6

Results

Polymerase chain reaction analysis and identification of B-cell clones

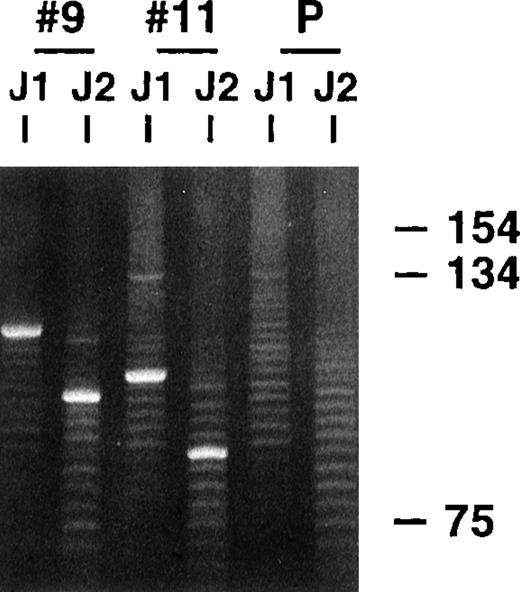

Parotid gland biopsy specimens of MALT lymphomas and several related LESA-associated lesions that demonstrated monoclonal bands using a standard heavy-chain PCR technique were obtained from 20 different patients. All the biopsies, except 2 recent cases of low-grade MALT lymphoma, were included in our earlier clinicopathologic study that did not analyze the VH genes used by the clones.15 The PCR clonality technique involves amplification across the highly variable CDR3 regions using consensus FW3 and JH primers and has excellent sensitivity and specificity, even with the poor quality DNA obtained from the paraffin-embedded tissue, because the products are typically small, being approximately 100 to 150 base pairs (bp) long.17 18Similar to the representative results shown in Figure1, single dominant monoclonal bands were identified in all 20 cases, along with polyclonal background ladders that reflect reactive B cells also present in the biopsy specimens, which generally have different sized CDR3s. Previous dilutional studies indicated that the clonal B cells needed to represent approximately 5% or more of the total B-cell population to be detected with this technique (unpublished observations).

PCR clonality analysis.

CDR3-related PCR products were obtained by amplifying lymphoma biopsy DNA with consensus FW3 and JH1 primers. Small aliquots of the resultant products were also secondarily amplified with FW3 and more internal JH2 primer. Shown are products from both FW3-JH1 and FW3-JH2 reactions for 2 cases and a polyclonal control after electrophoresis in an 8% acrylamide gel and staining with ethidium bromide. Prominent single monoclonal bands are seen in each case, along with fainter polyclonal ladders that reflect background B cells with different sized CDR3s that are also invariably present. The smaller sizes of the FW3-JH2 generated monoclonal bands simply reflect the more 5′ location of JH2 relative to JH1. Secondary amplifications with JH2 were performed to potentially enhance weaker monoclonal signals relative to the polyclonal background and to determine whether the JH2 primer would work with the clonalVH gene in PCR reactions to obtained more full length VH products.

PCR clonality analysis.

CDR3-related PCR products were obtained by amplifying lymphoma biopsy DNA with consensus FW3 and JH1 primers. Small aliquots of the resultant products were also secondarily amplified with FW3 and more internal JH2 primer. Shown are products from both FW3-JH1 and FW3-JH2 reactions for 2 cases and a polyclonal control after electrophoresis in an 8% acrylamide gel and staining with ethidium bromide. Prominent single monoclonal bands are seen in each case, along with fainter polyclonal ladders that reflect background B cells with different sized CDR3s that are also invariably present. The smaller sizes of the FW3-JH2 generated monoclonal bands simply reflect the more 5′ location of JH2 relative to JH1. Secondary amplifications with JH2 were performed to potentially enhance weaker monoclonal signals relative to the polyclonal background and to determine whether the JH2 primer would work with the clonalVH gene in PCR reactions to obtained more full length VH products.

Complete or nearly complete VH genes were successfully amplified from 15 of the 20 cases using a variety ofVH leader, FW1, FW2, and JHprimers. Our failure in 5 of the cases appeared to be due to the paraffin-extracted DNA being of lower quality, which prevented amplification of longer products the size ofVH genes. VHPCR products from selected reactions were cloned and repeatVH gene sequences identified in all cases, except in one, where the VH PCR products were directly sequenced. To ensure the repetitively isolated or clonalVH sequences represented the same clones identified earlier with the FW3-JH primers, the monoclonal FW3-JH bands were also purified and independently sequenced to obtain the “gold standard” CDR3 sequences (Figure2). This is an important step when working with paraffin-extracted DNA because repeat full-lengthVH sequences can occasionally be isolated that do not match the more reliable FW3-JH–generated CDR3 sequences when the DNA is of poor quality (personal observation).

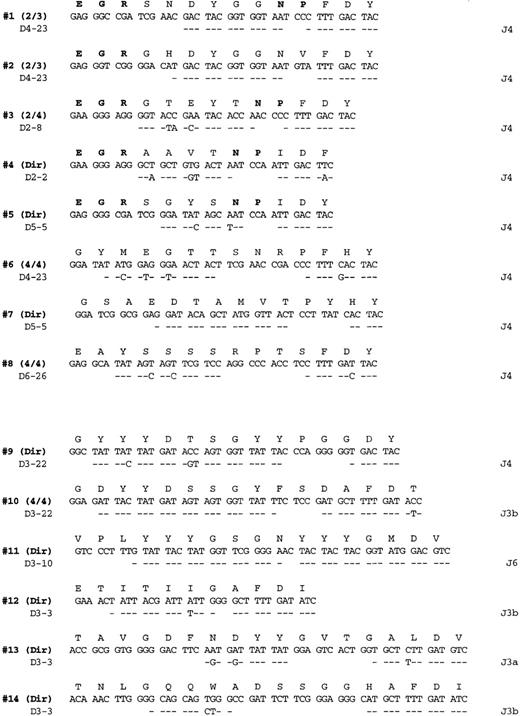

Salivary gland lymphoma CDR3 sequences.

PCR products obtained from amplification with FW3-JH1 or FW3-JH2 primers were either directly sequenced or cloned and multiple clones sequenced as indicated on the right (additional identical CDR3 sequences were also obtained from the more full length VH PCR products). Each sequenced is compared with the germline D and J segments showing the greatest homology where identity is indicated by a dash. The bolded entries in the deduced amino acid sequences from cases 1 to 5 highlight the conserved motifs at the V-D and D-J junctions referred to in the text.

Salivary gland lymphoma CDR3 sequences.

PCR products obtained from amplification with FW3-JH1 or FW3-JH2 primers were either directly sequenced or cloned and multiple clones sequenced as indicated on the right (additional identical CDR3 sequences were also obtained from the more full length VH PCR products). Each sequenced is compared with the germline D and J segments showing the greatest homology where identity is indicated by a dash. The bolded entries in the deduced amino acid sequences from cases 1 to 5 highlight the conserved motifs at the V-D and D-J junctions referred to in the text.

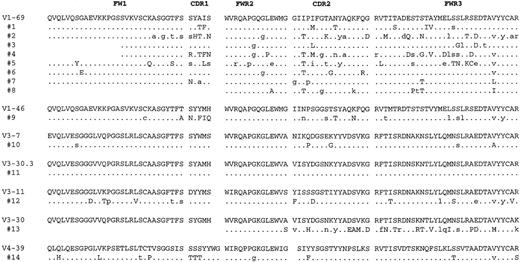

Analysis of VHgene segments

Of the 15 clonal VH genes identified, 14 were potentially functional in that no stop codons were present and the CDR3 sequences were in frame (Figures 2 and3). Comparing the clonalVH sequences with the known germline genes revealed that 8 of 14 were most homologous to a V1-69 gene segment, whereas the other 6 were most closely related to differentVH genes from theVH1 family (V1-46),VH3 family (V3-7, V3-30.3, V3-11, V3-30), and VH4 family (V4-39). Apparent point mutations were present in all but 1 of the clonal VH consensus sequences, with the average percentage homology being 95% (Table1). The majority of substitutions in theV1-69–derived genes appeared to be different from one another, with the exception of an isoleucine to threonine change (I to T in single letter amino acid code) in the third codon of CDR2, which was found in 5 of 8 consensus sequences (Figure 3). In addition to point mutations present in all the VH sequences from a given case, 5 cases (nos 1, 2, 4, 12, and 14) hadVH genes that also showed significant intraclonal sequence variation above our estimated Taq error rate of approximately 0.2%, indicative of ongoing somatic hypermutation (Table2). Although only one noncommon mutation was identified in the VH gene from case 9, it was present in 3 of 4 clones, suggesting it was acquired sequentially and was not from a polymerase error. Many of the other noncommon mutations in other cases were also shared among severalVH sequences.

Deduced amino acid sequences of the consensus lymphomaVH gene segments.

The sequences are compared to the amino acid sequences of the germlineVH gene segments showing the greatest homology where identity is indicated by a dot. The positions of mutations in the nucleotide sequences that would not result in a change in amino acid sequence are indicated by small case letters. Complete nucleotide consensus sequences for these cases are available from the GenBank database (accession numbers AF216816-AF216829).

Deduced amino acid sequences of the consensus lymphomaVH gene segments.

The sequences are compared to the amino acid sequences of the germlineVH gene segments showing the greatest homology where identity is indicated by a dot. The positions of mutations in the nucleotide sequences that would not result in a change in amino acid sequence are indicated by small case letters. Complete nucleotide consensus sequences for these cases are available from the GenBank database (accession numbers AF216816-AF216829).

Mutational analysis of consensus salivary gland lymphomaVH genes

| Case no. . | GermlineVH gene . | % homology . | CDR1 and 2 . | FW1, 2, and 3 . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R . | S . | R/S . | Random R/S . | R . | S . | R/S . | Random R/S . | |||

| 1 | V1-69 | 97 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 3.6 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| 2 | V1-69 | 91 | 6 | 5 | 1.2 | 3.6 | 5 | 11 | 0.45 | 3 |

| 3 | V1-69 | 98 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3.6 | 2 | 3 | 0.67 | 3 |

| 4 | V1-69 | 92 | 6 | 4 | 1.5 | 3.6 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 3 |

| 5 | V1-69 | 93 | 2 | 5 | 0.4 | 3.6 | 7 | 8 | 0.87 | 3 |

| 6 | V1-69 | 98 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3.6 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 3 |

| 7 | V1-69 | 98 | 1 | 3 | 0.3 | 3.6 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 8 | V1-69 | 97 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 3.6 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 9 | V1-46 | 94 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 4.2 | 1 | 7 | 0.14 | 2.8 |

| 10 | V3-7 | 98 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4.9 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 2.8 |

| 11 | V3-30.3 | 100 | ||||||||

| 12 | V3-11 | 94 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4.3 | 6 | 8 | 0.75 | 2.8 |

| 13 | V3-30 | 91 | 5 | 4 | 1.2 | 3.9 | 10 | 7 | 1.4 | 2.8 |

| 14 | V4-39 | 94 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4.5 | 7 | 4 | 1.7 | 2.6 |

| Case no. . | GermlineVH gene . | % homology . | CDR1 and 2 . | FW1, 2, and 3 . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R . | S . | R/S . | Random R/S . | R . | S . | R/S . | Random R/S . | |||

| 1 | V1-69 | 97 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 3.6 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| 2 | V1-69 | 91 | 6 | 5 | 1.2 | 3.6 | 5 | 11 | 0.45 | 3 |

| 3 | V1-69 | 98 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3.6 | 2 | 3 | 0.67 | 3 |

| 4 | V1-69 | 92 | 6 | 4 | 1.5 | 3.6 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 3 |

| 5 | V1-69 | 93 | 2 | 5 | 0.4 | 3.6 | 7 | 8 | 0.87 | 3 |

| 6 | V1-69 | 98 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3.6 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 3 |

| 7 | V1-69 | 98 | 1 | 3 | 0.3 | 3.6 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 8 | V1-69 | 97 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 3.6 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 9 | V1-46 | 94 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 4.2 | 1 | 7 | 0.14 | 2.8 |

| 10 | V3-7 | 98 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4.9 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 2.8 |

| 11 | V3-30.3 | 100 | ||||||||

| 12 | V3-11 | 94 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4.3 | 6 | 8 | 0.75 | 2.8 |

| 13 | V3-30 | 91 | 5 | 4 | 1.2 | 3.9 | 10 | 7 | 1.4 | 2.8 |

| 14 | V4-39 | 94 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4.5 | 7 | 4 | 1.7 | 2.6 |

Columns headed with “R” or “S” give the number of deduced replacement or silent mutations from the proposed germlineVH nucleotide sequences, respectively. “Random R/S” refers to the ratio of all possible replacement to silent mutations for the given areas as described by Chang and Casali.31

Intraclonal variation of lymphomaVH gene sequences

| Case no. . | Sequences analyzed (no.) . | Noncommon mutations* . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (no.) . | Frequency (%) . | Distribution . | ||

| 1 | 3 | 3 | 0.34 | (1-2/3), (1-1/3) × 2 |

| 2 | 4 | 3 | 0.26 | (3-2/4) |

| 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 | 3 | 5 | 0.67 | (1-2/3), (1-1/3) × 4 |

| 5 | 2 | 1 | 0.17 | (1-1/2) |

| 6 | 3 | 1 | 0.11 | (1-1/2) |

| 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8 | not cloned | |||

| 9 | 4 | 1 | 0.09 | (1-3/4) |

| 10 | 3 | 1 | 0.11 | (1-1/3) |

| 11 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| 12 | 4 | 12 | 0.94 | (4-3/4), (1-2/4), (1-1/4) × 7 |

| 13 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 14 | 5 | 9 | 0.61 | (3-3/5), (4-2/5), (1-1/5) × 2 |

| Case no. . | Sequences analyzed (no.) . | Noncommon mutations* . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (no.) . | Frequency (%) . | Distribution . | ||

| 1 | 3 | 3 | 0.34 | (1-2/3), (1-1/3) × 2 |

| 2 | 4 | 3 | 0.26 | (3-2/4) |

| 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 | 3 | 5 | 0.67 | (1-2/3), (1-1/3) × 4 |

| 5 | 2 | 1 | 0.17 | (1-1/2) |

| 6 | 3 | 1 | 0.11 | (1-1/2) |

| 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8 | not cloned | |||

| 9 | 4 | 1 | 0.09 | (1-3/4) |

| 10 | 3 | 1 | 0.11 | (1-1/3) |

| 11 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| 12 | 4 | 12 | 0.94 | (4-3/4), (1-2/4), (1-1/4) × 7 |

| 13 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 14 | 5 | 9 | 0.61 | (3-3/5), (4-2/5), (1-1/5) × 2 |

Noncommon mutations represent single nucleotide sequence differences identified in only a proportion of theVH clones analyzed. The column labeled “distribution” indicates the number ofVH sequences that contained the noncommon mutation, ie, (2-3/5) indicates that 2 of the noncommon mutations were identified in 3 of 5 VH clones analyzed. Noncommon mutations found in more than half of theVH clones were included in the consensus sequences.

Analysis of CDR3 sequences

The germline D and J segments assigned to the various clonalVH genes are listed in Figure 2. All 8 of the V1-69 derived chains used a J4 joining segment, whereas the others used mainly J3 sequences (4 of 6 cases). Although a variety of different D segments were used in different reading frames, 2 of theV1-69–derived genes (patient 1 and patient 2) used D4-23 in the same reading frame and had CDR3s that differed only by 3 of 14 amino acids. Several conserved amino-acid motifs that appeared to be encoded mostly by N nucleotides are evident in many of theV1-69 CDRs. For example, a glutamate, arginine, glycine motif (ERG single letter amino acid code) is present in 5 of the 8V1-69 CDR3 sequences at the V–D segment joint. In addition, an asparagine, proline motif (NP single letter code) is present at the D- J junction in 4 of the 8 sequences.

Discussion

This report greatly extends our earlier studies that suggested salivary gland MALT lymphomas express a limited repertoire ofVH gene segments.4,5 Of the 28 functional LESA-associated clonal VH genes now sequenced, 24 (86%) appear to be derived from only 3VH gene segments (Table3) and remarkably 17 (61%) use aV1-69 gene segment. Because the clonalVH gene CDR3 sequences were also obtained independently from sequencing FW3-JH–generated products, the limited repertoire cannot be accounted for by preferential amplification of certain genes with our VH primers. As mentioned above, multiple, closely related V1-69 alleles have been described that are termed either 51P1-like or 1263-like, based on several nucleotide differences within the CDR2 region.8 Of the 14 salivary gland lymphoma V1-69–derived segments, 12 appear to be derived from the 51P1 allele and 2 from a 51P1-like allele termed “2 M7” that only differs from 51P1 by 1 nucleotide in FW3. Because the calculated gene frequency of 1263-like and 51P1-like alleles is approximately 30% and 70%, respectively,10there also appears to be preferential use of specific V1-69alleles by these lymphomas. As further discussed below, this highly nonrandom repertoire suggests that an antigen is selecting certain B cells for malignant transformation in the salivary gland. As highlighted in Table 3, V1-69 has not been reported to be frequently used by MALT lymphomas that develop in the stomach.19-23 This suggests that gastric MALT lymphomas recognize different antigens from salivary gland MALT lymphomas and that pathogenesis of MALT lymphomas may have features that are specific for certain sites or locations.

Use of VH gene segments by clonal MALT lesions

| VH segment . | Salivary gland . | Stomach (gastric)3-151 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previous3-150 . | This study . | Total . | ||

| V1-69 (51p1, DP10) | 9/14 (64%) | 8/14 (57%) | 17/28 (61%) | 1/23 (4%) |

| V3-7(HG-19, DP54) | 4/14 (29%) | 1/14 (7%) | 5/28 (18%) | 4/23 (17%) |

| V3-11 (22-2B, DP35) | 1/14 (7%) | 1/14 (7%) | 2/28 (7%) | 0/23 |

| VH segment . | Salivary gland . | Stomach (gastric)3-151 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previous3-150 . | This study . | Total . | ||

| V1-69 (51p1, DP10) | 9/14 (64%) | 8/14 (57%) | 17/28 (61%) | 1/23 (4%) |

| V3-7(HG-19, DP54) | 4/14 (29%) | 1/14 (7%) | 5/28 (18%) | 4/23 (17%) |

| V3-11 (22-2B, DP35) | 1/14 (7%) | 1/14 (7%) | 2/28 (7%) | 0/23 |

MALT = mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue.

The 14 independent clones were identified in a total of 17 biopsy specimens from 10 different patients where 2 biopsies were analyzed for 7 of the patients.4 5 Two patients had 2 salivary biopsies that contained different V1-69 clones, ie, 4 of the 9 “previous” V1-69 VH genes came from 2 patients.

This report also establishes that salivary gland lymphoma–expressedV1-69 genes often have remarkably similar CDR3 sequences. All 8 V1-69 CDR3s described in these studies use a J4 segment and were between 12 and 14 amino acids long. Although a variety of different D segments were generally used, 5 of the 8 V1-69 CDR3s had the amino acid motif glutamate, glycine, arginine (EGR single letter amino acid code) at the V-D junction that appeared to be encoded by mostly different N-nucleotide sequences. Moreover, 4 of the 5 CDR3s that contained an ERG motif also had a conserved NP motif located at the D-J junction, that again appeared to be mostly encoded by N-nucleotides. In part, because of these conserved N-nucleotides motifs and preferential use of JH4, 2 of the unrelated lymphomas, which used the same D segment in the same reading frame, had CDR3s that only differ by 3 of 14 amino acids. Our previously reported V1-69 salivary gland lymphoma VH genes showed only possible overuse of JH4 (7 of 9) sequences, without revealing the conserved ERG motif (0 of 9) or NP motif (1 of 9).4 5

The heavy-chain CDR3 is the most variable part of the conventional antigen binding site and often plays a critical role in determining immunoglobulin binding specificity.13,14,24 Because of the tremendous potential variability, different antibodies that recognize the same antigen usually have dissimilar CDR3 sequences.25,26 Antigens that elicit antibodies with similar CDR3 features have been described, but are mainly limited to simple peptides, haptens, and polysaccharides.27 Therefore, the high degree of similarity among the salivary gland lymphomas CDR3 sequences suggests that some may recognize similar or perhaps identical epitopes.

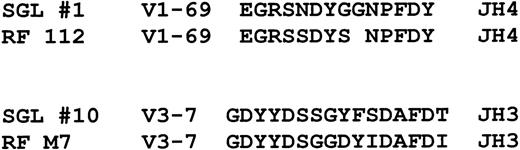

Although the antigen specificity of the salivary gland lymphoma antibodies is presently unknown, our VHgene analysis suggests that many may have rheumatoid factor activity or reactivity toward IgG heavy chains. Borretzen et al28reported that V1-69 rheumatoid factors have characteristic CDR3s that are approximately 12 to 14 amino acids long, preferentially use JH4, and have the conserved amino acid motifs EGR and NP at the V-D and D-J junctions, respectively, similar to what we have found for salivary gland lymphomas (Figure4). It was also noted that these features did not appear to be present in other nonrheumatoid factorV1-69 CDR3 sequences. In addition, antibodies with rheumatoid factor activity encoded by V3-7 VHsequences were noted to have different characteristic CDR3 sequences that are typically 16 to 17 amino acids long, preferentially use JH3 and D3-22 segments, and have a glycine as the first amino acid.28 Interestingly, salivary gland lymphomasVH genes encoded by V3-7, one of which was identified in this study, also appear to have CD3s with similar characteristics as shown in Figure 4. The possibility that many of the salivary gland lymphoma immunoglobulins have rheumatoid factor activity is also supported by reports of frequently finding local salivary gland production of rheumatoid factor in patients with Sjögren's syndrome29 and the frequent occurrence of mixed type II cryoglobulins (monoclonal rheumatoid factors, as described below) in these patients.30

Comparison of 2 salivary gland lymphoma CDR3 sequences to CDR3 sequences used by V1-69 and V3-7 encoded antibodies with rheumatoid factor activity.

The rheumatoid factor sequences are from Borretzen et al.28The gap in RF112 was made to highlight the sequence similarities.

Comparison of 2 salivary gland lymphoma CDR3 sequences to CDR3 sequences used by V1-69 and V3-7 encoded antibodies with rheumatoid factor activity.

The rheumatoid factor sequences are from Borretzen et al.28The gap in RF112 was made to highlight the sequence similarities.

The frequent use of V1-69 and similar CDR3 sequences by these lymphomas suggests that B cells with certain binding specificities are selected for clonal expansion and transformation in the salivary gland. This hypothesis is also supported by several considerations from analyses of apparent point mutations present in all but 1 of the lymphoma VH sequences described in this report. First, the ratios of deduced replacement (R) and silent (S) mutations found in CDR1 and CDR2 were generally lower than expected if the mutations occurred randomly. This is particularly evident in the 5 most informative cases with 7 or more mutations in CDR1 and CDR2 (patients 2, 4, 5, 9, and 13; Table 1), in which the observed R/S ratios were much lower than the R/S ratios expected by random mutation alone.31 Finding lower R/S mutation ratios than expected by chance suggests that there is selection against R mutations or negative selection that can occur because certain CDR residues are necessary for antigen binding and cannot be altered. Second, negative selection of R mutations was also observed in the FWRs, which was again especially evident in the VH genes with the greatest number of mutations and potentially most informative (nos 2, 4, 5, 9, 12, 13, and 14). Evidence for negative selection of R mutations in FWRs is often found in VH genes that encode functional immunoglobulin molecules because certain amino acid residues need to be preserved to maintain function.32 In this case, it suggests that the maintenance of the immunoglobulin function is important for lymphoma cell survival or growth.

In addition to mutations present in all the clonally relatedVH sequences, some of theVH genes from a given case showed significant levels of intraclonal heterogeneity or mutations, not common to all the related VH sequences indicative of ongoing Ig gene hypermutation. Ongoing Ig gene mutation suggests that antigen binding, which is thought to trigger the Ig gene mutator, may still be simulating lymphoma cell growth in these cases.33 Further support for active antigenic stimulation of lymphoma cell growth comes from analysis of the distribution and type of noncommon mutations found in the 2VH genes with the greatest number of noncommon mutations described in this study. As highlighted in Table4, there appears to be selection against newly generated R mutations in both the CDRs and FWRs. Evidence suggesting that newly generated R mutations in the lymphoma VH genes can be negatively selected was also described in our previous studies in which greater numbers of these mutations could be evaluated.4

Distribution of noncommon mutations in the 2VH genes with the greatest number of noncommon mutations

| Case no. . | CDR1 and 2 . | FW1, 2, and 3 . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R5-150 . | S . | R/S . | Random R/S . | R . | S . | R/S . | Random R/S . | |

| 12 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4.3 | 5 | 4 | 1.2 | 2.8 |

| 14 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4.5 | 5 | 3 | 1.7 | 2.6 |

| Case no. . | CDR1 and 2 . | FW1, 2, and 3 . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R5-150 . | S . | R/S . | Random R/S . | R . | S . | R/S . | Random R/S . | |

| 12 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4.3 | 5 | 4 | 1.2 | 2.8 |

| 14 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4.5 | 5 | 3 | 1.7 | 2.6 |

Same format as in Table 1. Noncommon mutations present in more than 1 sequence are counted only once.

Besides salivary gland MALT lymphomas, V1-69 gene segments also appear to be frequently used by CLL, although to a lesser degree, being found in approximately 10% to 20% of cases.10-12 Unlike salivary gland lymphomas, however, the V1-69 genes in most cases of CLL are usually unmutated.10-12 Cases of CLL usingV1-69 gene segments also have been reported to have CDR3s with distinctive molecular features.10 It is clear, however, that the distinctive V1-69 salivary gland lymphoma CDR3 sequences we have identified in this study differ from those described for V1-69 CLL in typically being longer, using predominately JH4 rather than JH6 joining segments, and also showing conserved amino acid motifs at the V-D and D-J junctions (Table5). These differences in expressed V1-69 genes further support salivary gland lymphoma being distinct from CLL and also suggest that the antigens recognized by CLL and salivary gland MALT lymphomas that potentially may be involved in malignant transformation will be different. Finding frequent use of V1-69genes in malignancies with different characteristics CDR3s also raises the possibility that heavy chains encoded by V1-69 segments may have some superantigen-like feature that predisposes B cells to become neoplastic.13

Comparison of V1-69 CDR3 sequences

| . | SG-MALT4-150 . | CLL4-151 . |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 13.9 ± 1.5 | 19.0 ± 3.5 |

| JH4 | 15/17 (88%) | 1/26 (4%) |

| JH6 | 0/17 | 12/26 (46%) |

| 1st AA-E | 10/17 (59%) | 1/26 (4%) |

| 5′J AA-P | 8/17 (47%) | 0/26 |

| . | SG-MALT4-150 . | CLL4-151 . |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 13.9 ± 1.5 | 19.0 ± 3.5 |

| JH4 | 15/17 (88%) | 1/26 (4%) |

| JH6 | 0/17 | 12/26 (46%) |

| 1st AA-E | 10/17 (59%) | 1/26 (4%) |

| 5′J AA-P | 8/17 (47%) | 0/26 |

SG-MALT = salivary gland mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue; CLL = chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

SG-MALT data from this and previous studies.4 5 1st AA-E refers to the first amino acid at V-D junction being glutamate (E), whereas 5′J AA-P refers to a proline being immediately 5′ to the J segment start (Figure 2).

CLL data from Johnson et al.10

Hepatitis-C–associated immunocytoma appears to represent another B-cell neoplasm that frequently uses V1-69 because 4 of 8 immunocytoma VH genes that were sequenced in a recent study used V1-69.34 Immunocytomas, which are also termed lymphoplasmacytic lymphomas in the recent WHO lymphoma classification system,35 can sometimes be difficult to differentiate histologically from MALT-type lymphomas, have similar immunophenotypes, and may be closely related. Hepatitis-C is thought to be the major cause of type II mixed cryoglobulins that represent monoclonal IgM rheumatoid factors complex to polyclonal IgG.36 Presumably, all the V1-69hepatitis-C–associated immunocytomas in the previously mentioned study by Ivanovski et al34 were producing monoclonal rheumatoid factors because these patients also had type II mixed cryoglobulins. Because of this, the use of V1-69 by hepatitis-C lymphomas was not completely unexpected because it is well known that monoclonal rheumatoid factors from mixed cryoglobulins frequently express the G6 cross-reactive idiotype that is a marker for 51p1-like alleles ofV1-69.10,37 Besides the frequent use ofV1-69, hepatitis-C–associated immunocytomas may also have CDR3 sequences similar to those seen in salivary gland lymphomas because 3 of the 5 used JH4, and 2 started with EG (none had EGR), although none had an NP motif at the D-J junction. TheVH gene similarities and presumed rheumatoid factor reactivity of the hepatitis-associated immunocytomas support these neoplasms being closely related to salivary gland MALT lymphomas in terms of pathogenesis. Because hepatitis-C virus does not appear to be a likely cause of LESA or salivary gland lymphoma,38 39 the use of similarVH genes may represent selection by a similar antigen that is generated or up-regulated as a result of localized chronic immune system stimulation.

In conclusion, this study helps to clearly establish that salivary gland MALT lymphomas express an extremely limited repertoire ofVH genes with conserved CDR3 structures. The data are consistent with a model in which only certain B cells are preferentially selected for transformation in the salivary gland which have immunoglobulin molecules with the ability to bind an as yet undefined antigen. Previous reports indicating there is an increased frequency of B cells with the G6 and other nonactive idiotypes in salivary gland biopsy specimens from patients with Sjögren's syndrome who do not have lymphoma suggests the selection process is chronic in nature.3,40 Our analysis of mutations in salivary gland lymphoma VH genes also is consistent with an antigen-driven selection process that may be prevented from undergoing affinity maturation through normal tolerance mechanisms similar to what has been described for V1-69antibodies with rheumatoid factor activity.41 If it can be shown that many of the salivary gland lymphomas do indeed have rheumatoid factor activity, which is suggested by the distinctiveV1-69 and V3-7 CDR3 sequences, it will also be important to determine what other antigens the lymphomas may recognize because the rheumatoid factor activity could represent a cross-reactivity.42,43 In addition, because heavy chains from antibodies with rheumatoid factor activity can be encoded by a variety different VHgenes,28 44 the mechanism whereby the limitedVH repertoire is selected would still need to be explained.

Supported by the Pathology Educational and Research Foundation (University of Pittsburgh) and a Translational Research Grant from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (D.W.B.).

Reprints:David W. Bahler, Department of Pathology, Presbyterian University Hospital, Rm C604, 200 Lothrop St, Pittsburgh, PA 15213; e-mail: bahlerdw@msx.upmc.edu.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal