Abstract

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) shows evidence of familial aggregation, but the genetic basis is poorly understood. The existence of a linkage between HLA and Hodgkin lymphoma, another B-cell disorder, coupled with the fact that CLL is frequently associated with autoimmune disease, led to the question of whether the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region is involved in familial cases of CLL. To examine this proposition, 5 microsatellite markers on chromosome 6p21.3 were typed in 28 families with CLL, 4 families with CLL in association with other lymphoproliferative disorders, and 1 family with splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes. There was no evidence of linkage in these families to chromosome 6p21.3. The best estimates of the proportions of sibling pairs with CLL that share 0, 1, or 2 MHC haplotypes were not significantly different from the null expectation. This implies that genes within the MHC region are unlikely to be the major determinants of familial CLL.

Introduction

In Western countries, leukemia affects approximately 1 in 50 of the population.1 Of the many subtypes, B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common, constituting about one third of all cases.2 Its incidence rate increases logarithmically from age 35 years, with the median age at diagnosis being 65 years.3

Epidemiologic studies strongly suggest that a subset of CLL cases have an inherited basis. More than 40 separate reports have described the clustering of CLL in small families, occasionally in association with other lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs).4 Systematic analyses of the risk in relatives indicate that the risk of CLL is increased 3-fold in relatives of patients.3,5-9 The genetic basis for predisposition to CLL is unknown. The difficulty of ascertaining large CLL families with multiple available affected members limits the power of a genome-wide screen for linkage and makes evaluation of candidate loci a more feasible approach. The established relation between HLA and Hodgkin lymphoma, another B-cell disorder,10,11 coupled with the fact that CLL is associated with autoimmune disease,12-14led us to examine whether the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region is involved in familial cases of CLL. In this study, we examined this proposition by conducting an analysis for linkage at chromosome 6p21.3 in families with CLL and associated LPDs.

Study design

Patient selection

Thirty-three families were ascertained by hematologists in the United Kingdom, Norway, Israel, Italy, Ireland, Germany, Portugal, The Netherlands, and Australia. The diagnoses of B-CLL and other LPDs in family members were established in all cases using standard clinicohematologic and immunologic criteria. Samples were obtained with informed consent and ethical review board approval. DNA was salt-extracted from EDTA blood samples using a standard sucrose lysis method.

Genotyping

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed at the following microsatellite loci: D6S299, D6S464, D6S276, D6S273, and D6S291. PCR primer sequences and reaction conditions were taken from the Marshfield database (http://www.marshmed.org). Dye-labeled PCR products were detected on ABI 377 DNA sequencers and analyzed using Genescan and Genotyper software.

Statistical methods

Multipoint analysis was performed with the program GENEHUNTER15 using the nonparametric LOD (NPL)-all statistic, which calculates approximate P values in a model free analysis. The contribution of the MHC toward the overall susceptibility to CLL was determined from the allele-sharing probabilities between affected sibling pairs using the method of Risch.10 This method assesses the magnitude of linkage of a locus with disease in terms of the ratio λ (the relative risk, ie, the observed frequency of sharing of zero alleles identical by descent [IBD] at a locus with what is expected in the absence of linkage). If Z0 is the proportion of affected sibling pairs sharing zero parental alleles IBD at the locus, the sibling relative risk, λs, is given by 1/4Z0. This formula holds true regardless of the mode of inheritance at the disease locus, the number of alleles and their frequencies, the penetrance, and the population prevalence of disease. The 95% confidence intervals for λs are given by the following16:

In this equation, ν1 is given by (4λs/n) × (1 − 1/4λs); and n indicates the number of affected sibling pairs.

Haplotype-sharing probabilities among affected sibling pairs were assessed for the purpose of deriving λs using the program MAPMAKER-SIBS.17 Marker allele frequencies were obtained from the Marshfield database (http://www.marshmed.org) and were similar to the relative frequencies seen across all the families typed. Distances between markers were also obtained from the Marshfield database.

Results and discussion

Thirty-two families were used in the linkage analysis. Table 1 details their clinical characteristics. The first 28 of these families had at least 2 members affected with CLL. Of these families, numbers 42 and 65 also had family members affected with other LPDs. Families 44, 47, 59, and 80 had one family member affected with CLL and a second with another LPD. Family 102 included 2 sisters with splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes.

Details of the families studied

| Family no. . | Index case . | Age at diagnosis, y . | Relative . | Age at diagnosis, y . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Female | 56 | Sister | 66 |

| Identical twin | 59 | |||

| 5 | Female | 54 | Brother | 46 |

| Brother | 47 | |||

| Father | 71 | |||

| 6 | Female | 42 | Brother | 40 |

| Mother | 69 | |||

| 8 | Male | 70 | Brother | 76 |

| Brother | 55 | |||

| 11 | Female | 69 | Sister | 61 |

| 13 | Female | 70 | Brother | 58 |

| 15 | Male | 63 | Sister | 61 |

| 18 | Female | 74 | Sister | 73 |

| 20 | Male | 64 | Brother | 66 |

| 36 | Male | 81 | Sister | 77 |

| Brother | 64 | |||

| 37 | Male | 85 | Sister | 86 |

| Sister | 79 | |||

| Brother | 60 | |||

| 38 | Male | 77 | Brother | 71 |

| 39 | Female | 60 | Sister | 51 |

| 40 | Male | 71 | Sister | 48 |

| 41 | Male | 35 | Sister | 51 |

| 42 | Male | 59 | Second cousin | 43 |

| Brother (HD) | 52 | |||

| 45 | Male | 61 | Sister | 52 |

| 46 | Female | 61 | Sister | 59 |

| 48 | Female | 45 | Sister | 51 |

| 49 | Male | 69 | Sister | 80 |

| 60 | Male | 55 | Sister | 49 |

| 63 | Male | 57 | Sister | 43 |

| 64 | Male | 62 | Brother | 61 |

| 65 | Male | 62 | Brother | 70 |

| Sister (myeloma) | 75 | |||

| 78 | Male | 32 | Uncle | 54 |

| Uncle | 50 | |||

| 85 | Male | 60 | Brother | 49 |

| 96 | Male | 65 | Brother | 61 |

| 98 | Male | 67 | Brother | 64 |

| 44 | Female | 39 | Brother (HCL) | 39 |

| 47 | Female | 36 | Male cousin (NHL) | 64 |

| 59 | Male | 44 | Brother (NHL) | 48 |

| 80 | Male | 51 | Brother | 58 |

| Male cousin (HCL) | 46 | |||

| 102 | Female (SLVL) | 70 | Sister (SLVL) | 65 |

| Family no. . | Index case . | Age at diagnosis, y . | Relative . | Age at diagnosis, y . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Female | 56 | Sister | 66 |

| Identical twin | 59 | |||

| 5 | Female | 54 | Brother | 46 |

| Brother | 47 | |||

| Father | 71 | |||

| 6 | Female | 42 | Brother | 40 |

| Mother | 69 | |||

| 8 | Male | 70 | Brother | 76 |

| Brother | 55 | |||

| 11 | Female | 69 | Sister | 61 |

| 13 | Female | 70 | Brother | 58 |

| 15 | Male | 63 | Sister | 61 |

| 18 | Female | 74 | Sister | 73 |

| 20 | Male | 64 | Brother | 66 |

| 36 | Male | 81 | Sister | 77 |

| Brother | 64 | |||

| 37 | Male | 85 | Sister | 86 |

| Sister | 79 | |||

| Brother | 60 | |||

| 38 | Male | 77 | Brother | 71 |

| 39 | Female | 60 | Sister | 51 |

| 40 | Male | 71 | Sister | 48 |

| 41 | Male | 35 | Sister | 51 |

| 42 | Male | 59 | Second cousin | 43 |

| Brother (HD) | 52 | |||

| 45 | Male | 61 | Sister | 52 |

| 46 | Female | 61 | Sister | 59 |

| 48 | Female | 45 | Sister | 51 |

| 49 | Male | 69 | Sister | 80 |

| 60 | Male | 55 | Sister | 49 |

| 63 | Male | 57 | Sister | 43 |

| 64 | Male | 62 | Brother | 61 |

| 65 | Male | 62 | Brother | 70 |

| Sister (myeloma) | 75 | |||

| 78 | Male | 32 | Uncle | 54 |

| Uncle | 50 | |||

| 85 | Male | 60 | Brother | 49 |

| 96 | Male | 65 | Brother | 61 |

| 98 | Male | 67 | Brother | 64 |

| 44 | Female | 39 | Brother (HCL) | 39 |

| 47 | Female | 36 | Male cousin (NHL) | 64 |

| 59 | Male | 44 | Brother (NHL) | 48 |

| 80 | Male | 51 | Brother | 58 |

| Male cousin (HCL) | 46 | |||

| 102 | Female (SLVL) | 70 | Sister (SLVL) | 65 |

Relevant condition is CLL unless indicated. HD indicates Hodgkin disease; HCL, hairy cell leukemia; NHL, non-Hodgkin leukemia; SLVL, splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes.

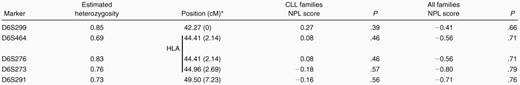

Table 2 shows the nonparametric LOD (NPL) scores for linkage of CLL to chromosome 6p21.3 microsatellite markers for CLL families and for all families. Four of the markers reside within the HLA cluster, and all 5 span a region of 7.23 cM. These data provide no evidence of linkage of CLL to 6p21.3 markers in these families. The maximum NPL score was 0.27 at HLA (P > .2) for the CLL families. The affected-sibling-pair MAPMAKER-SIBS analysis of the CLL families showed that the best estimates of the proportions of sibling pairs that share 0, 1, or 2 haplotypes at the MHC region (at D6S273) were their null expectations (ie, 0.25, 0.50, and 0.25, respectively). On this basis, the sibling relative risk attributable to the MHC region is 1.0. The upper 95% confidence limit for the sibling relative risk, taking into account study size, is 1.8.

Multipoint NPL scores for linkage to chromosome 6p21.3 markers

Ordered from telomere; relative position given in parentheses.

Vertical bar indicates position of HLA region.

We performed this linkage analysis of chromosome 6p21.3 to determine whether genes within the MHC region are implicated in familial CLL for 2 reasons. First, an association between CLL and autoimmune disease has been reported.12 Patients with CLL frequently share common HLA haplotypes with relatives who have autoimmune disease. The majority of B-cell CLL is CD5+, and B cells are implicated in autoimmunity. Hence, genetic determinants of CD5+ B-cell proliferation or differentiation are likely to be involved in both B-CLL and autoimmune disease.12 The notion of a relation between CLL and autoimmune disease is supported by animal studies using congenic New Zealand mouse strains.13,14 Second, Hodgkin lymphoma shows a strong linkage to HLA.10,11 The underlying basis of linkage is not through a common haplotype, but it appears that certain HLA-DPB1 alleles may affect susceptibility and resistance to specific subtypes of Hodgkin lymphoma.11 18 In Hodgkin disease, the allele-sharing probabilities between affected siblings suggest that the HLA locus is likely to explain a 2-fold sibling relative risk, with more than half of all cases arising in susceptible individuals. Although our linkage analysis does not support a similar conclusion for CLL, the 95% confidence limit for the estimate of the sibling relative risk attributable to HLA does not preclude that variation within HLA or MHC is a determinant of CLL susceptibility in some instances. Our findings do, however, imply that genes within the MHC region are unlikely to be the sole or major determinants of familial CLL.

Acknowledgments

We thank the families who took part in this study, and we also are grateful to Benjamin Hilditch for data management.

Supported by the Leukaemia Research Fund and BREAKTHROUGH Breast Cancer.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

R. S. Houlston, Institute of Cancer Research, 15 Cotswold Rd, Sutton, United Kingdom; e-mail:r.houlston@icr.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal