Abstract

This meta-analysis focuses on 2 prospective studies in patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) and thromboembolic complication (TEC) who were treated with lepirudin (n = 113). Data were compared with those of a historical control group (n = 91). The primary endpoint (combined incidence of death, new TEC, and limb amputation) occurred in 25 lepirudin-treated patients (22.1%; 95% CI, 14.5%-29.8%): 11 died (9.7%; 95% CI, 4.9%-16.8%), 7 underwent limb amputation (6.2%; 95% CI, 2.5%-12.3%), and 12 experienced new TEC (10.6%; 95% CI, 5.8%-18.3%). The risk was highest in the period between diagnosis of HIT and the start of lepirudin therapy (combined event rate per patient day 6.1%). It markedly decreased to 1.3% during lepirudin treatment and to 0.7% in the posttreatment period. From the start of lepirudin therapy to the end of follow-up, lepirudin-treated patients had consistently lower incidences of the combined endpoint than the historical control group (P = .004, log-rank test), primarily because of a reduced risk for new TEC (P = .005). Thrombin–antithrombin levels in the pretreatment period (median, 43.9 μg/L) decreased after the initiation of lepirudin (at 24 hours ± 6 hours; median, 9.18 μg/L.) During treatment with lepirudin, aPTT ratios of 1.5 to 2.5 produced optimal clinical efficacy with a moderate risk for bleeding, aPTT ratios lower than 1.5 were subtherapeutic, and aPTT levels greater than 2.5 were associated with high bleeding risk. Bleeding events requiring transfusion were significantly more frequent in patients taking lepirudin than in historical control patients (P = .02). In conclusion, this meta-analysis provides further evidence that lepirudin is an effective and acceptably safe treatment for patients with HIT.

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a well-known complication of heparin therapy.1 It develops in up to 3% of patients treated with unfractionated heparin.2Immune-mediated HIT typically is manifested 5 to 10 days after the start of heparin therapy; the mechanism appears to involve the development of antibodies of the IgG class, which bind to heparin platelet factor 4 (PF4) complexes.3,4 The interaction of these antigen–antibody complexes with endothelial cells5-7and platelets8 9 may contribute to the development of new thrombi.

Thrombin plays a central role in HIT-related thromboembolic complication (TEC). Thrombin generation is enhanced in HIT by the concomitant activation of platelets,10 the generation of platelet microparticles,11 and the alteration of endothelial cells.5 Immediate cessation of heparin treatment is necessary when HIT develops. However, thrombin generation continues even after the cessation of heparin,12,13 and many patients require further parenteral anticoagulation because of their underlying disease, especially if they have experienced a recent TEC. A nonheparin anticoagulant that does not cross-react with HIT antibodies, such as hirudin, may be appropriate for this purpose. Hirudin is a direct inhibitor of thrombin and acts independently of cofactors such as antithrombin14; unlike heparin, hirudin is not inactivated by PF4 and may be more effective in the presence of platelet-rich thrombi.15 Hirudin can also inhibit thrombin that is bound to fibrin or fibrin-degradation products.16 17 It should, therefore, be an ideal anticoagulant in HIT, a syndrome triggered by intravascular platelet activation and thrombin generation and often complicated by new TEC.

We evaluated the recombinant hirudin lepirudin (Refludan; Aventis Pharma, Frankfurt, Germany) in patients with HIT in 2 prospective studies of similar design.12 18 At the time the studies were conducted, no active comparator was available, and a placebo-controlled trial was considered ethically inappropriate; therefore, clinical outcomes of patients in the studies were compared with those of a historical control group.

In the HAT-1 trial,18 lepirudin treatment resulted in a statistically significant reduction of new TEC, limb amputation, or death (combined endpoint). Although the HAT-2 trial showed a similar trend toward fewer clinical events with lepirudin, the results did not reach statistical significance.12 The reasons for the different outcomes in the 2 studies are still unclear. Each study included patients with thrombocytopenic HIT with and without TEC at baseline. This meta-analysis was designed to evaluate the effects of lepirudin in the patients with TEC at baseline, for whom the need for continued parenteral anticoagulation is generally accepted. Taken together, HAT-1 and HAT-2 provide the largest prospective data collection published to date of such severely affected patients with HIT. The objectives of the meta-analysis were to evaluate the clinical outcomes of patients with HIT and TEC who were treated with lepirudin and to compare them with the clinical outcomes of historical control patients who did not receive lepirudin, to evaluate the therapeutic aPTT ranges for lepirudin, and to assess potential cofactors influencing the outcomes in these patients, such as sex, age, patient population (surgery vs medical and others), and comedications (aspirin, coumarin, thrombolytics).

Patients and methods

Patients

Patients administered lepirudin were selected from 2 prospective clinical studies,12,18 and control patients were selected from a registry of patients who did not receive lepirudin (or any other hirudin).18 The registry was established before lepirudin was available. Diagnoses for all patients (lepirudin study and historical control) were made in the same laboratory using the same methods, and all patients were enrolled consecutively. Patients qualified for the meta-analysis if they had arterial or venous thromboembolism and a diagnosis of HIT based on clinical criteria (decrease in platelet count by 50% or more or to less than 100 × 109/L, new TEC during heparin administration, or both conditions) and based on laboratory-confirmed HIT antibodies. The heparin-induced platelet activation test was used to detect HIT antibodies.19 20 Exclusion criteria were age younger than 18 years, no ongoing thrombosis, missing date of laboratory confirmation of HIT, more than 21 days between onset of clinical symptoms (thrombocytopenia or TEC during heparin treatment) and laboratory confirmation of HIT, cardiopulmonary bypass, and start of therapy more than 60 days after laboratory confirmation of HIT.

Treatment regimens

Lepirudin (Refludan; Aventis Pharma) treatment regimens used in the 2 prospective studies were as follows. In regimen A1, patients with HIT and thrombosis were administered a 0.4 mg/kg intravenous (IV) loading dose and then 0.15 mg/kg per hour of continuous IV infusion, adjusted according to aPTT. In regimen A2, patients with HIT and thrombosis who were receiving thrombolysis were administered a 0.2 mg/kg IV loading dose and then 0.1 mg/kg per hour continuous IV infusion adjusted according to aPTT.

The aPTT was used to monitor lepirudin treatment. Based on studies in patients without HIT,21 the therapeutic range was predefined as a 1.5- to 2.5-fold prolongation of the baseline aPTT value. If the patient's baseline aPTT value was unavailable, the mean of the laboratory normal range was used. As described previously,12 the lepirudin dosage was reduced in patients with serum creatinine levels higher than 1.5 mg/dL (133 μmol/L). Historical control patients were treated at the discretion of the treating physician. Management decisions were made by the treating physician.

Clinical outcome

Prespecified clinical efficacy variables included new TEC, limb amputations, and death. Patients were monitored daily for platelet counts and for new TEC from the time of laboratory confirmation of HIT until 14 days after the end of treatment. In the first 56 patients thrombin–antithrombin complexes (Enzygnost; Dade–Behring, Marburg, Germany) were assessed before treatment with lepirudin, 4, 12, 24, and 36 hours after the start of lepirudin, and then daily until the end of treatment.

Because laboratory confirmation of HIT was an absolute inclusion criterion, there was a time delay between suspicion of HIT and start of lepirudin treatment. To evaluate whether a clinical suspicion of HIT would justify immediate treatment with lepirudin or whether confirmation of the tentative diagnosis by laboratory assay should be sought first, average combined outcome rates per patient day were estimated for each of the following periods: before treatment, or after laboratory confirmation of HIT and before the start of lepirudin treatment; during lepirudin treatment; and after treatment, extending to 2 weeks after the cessation of lepirudin treatment. Clinical safety variables included any bleeding and bleeding requiring transfusion during treatment.

Comparison with historical control.

Outcome data from patients in the prospective trials were compared with those from patients in the historical control group. The primary endpoint of the comparison was the cumulative incidence of the combined endpoint of death, new TEC, and limb amputation. Because no lepirudin effect could be expected during the pretreatment interval, the start of treatment was considered the most relevant starting point for comparison with the historical controls.

Determination of the therapeutic aPTT range for lepirudin and identification of potential covariates affecting outcome.

To determine the therapeutic range of aPTT prolongation for lepirudin, the association between aPTT levels and clinical outcome was assessed. Lepirudin-treated patients were classified as having aPTT ratios that were low (1.0 to 1.5), medium (1.5 to 2.5), or high (greater than 2.5). Patients moved from one aPTT class to another depending on various modifications of treatment (eg, delayed start of therapy, dose adjustments, dose interruptions, treatment discontinuation). Risk ratio (RR) for the combined incidence of new TEC, limb amputation, death, and bleeding were calculated for aPTT class and were compared with the historical control, taking into account additional potential prognostic variables—sex, age, patient population (surgery vs medical and others), and comedication (aspirin, coumarin, thrombolytics).

Determination of the impact of lepirudin on the monitoring of vitamin K antagonists (phenprocoumon).

The impact of lepirudin on parameters used for monitoring the extrinsic coagulation pathway (INR or Quick value) was determined by comparing the values up to 8 hours before the start of lepirudin, with those obtained 4 to 8 hours after the start of lepirudin and the values 8 hours before the end of lepirudin with those obtained from 8 to 36 hours after the cessation of lepirudin. Because this was not a prespecified parameter of the studies, we did not document the INR and, therefore, had to use the Quick values of the different laboratories. This did not allow an absolute comparison but only a description of relative changes.

Statistical methods

Average combined event rates per patient day were calculated on the basis of the endpoint events that were observed in the respective study period. Rates in the pretreatment period were descriptively compared with those in the treatment and posttreatment periods.

Comparison with the historical control group was conducted according to the Kaplan-Meier method22 using a time-to-event analysis starting with the initiation of study treatment. Cumulative incidences of clinical events were estimated using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and were not subjected to statistical inference. Time from start of treatment to onset of a clinical event (defined as new TEC, limb amputation, or death) in the lepirudin group was compared with that in the historical control group using the log-rank test.22 In the historical control group, the first therapeutic option chosen within 2 days after laboratory confirmation of HIT was identified and used to define the start of treatment.

A Cox proportional hazards model was used to reassess the therapeutic aPTT range compared with the event rate in the historical control group. In this model, the aPTT ratios were considered time-dependent covariates. Other potential factors that were modeled as simple covariates included sex, age (younger than 65 vs older than 65 years), patient population (surgery vs medical and others), aspirin treatment, coumarin treatment, and thrombolytic treatment.

Cumulative incidences of any bleeding and bleeding requiring transfusion were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The differences between the lepirudin and historical control groups in time to bleeding were compared using the log-rank test.

Quick values were compared by Wilcoxon test.

Results

Lepirudin-treated patients and historical control population

Two hundred four patients were included in the meta-analysis, 113 in the lepirudin group and 91 in the historical control group. Baseline characteristics of all patients are summarized in Table1. Patients in the lepirudin group were generally younger than those in the historical control group (mean ages, 57 vs 64 years, respectively). Each patient had an ongoing thrombosis at study entry, but not all experienced TEC during or shortly after heparin treatment (ie, HIT related). In the remaining patients, spontaneous thrombosis was the indication for heparin treatment. Of the 113 lepirudin-treated patients, 57 had platelet counts lower than 100 × 109/L at the start of lepirudin treatment. The number of patients with TEC during heparin therapy was higher in the historical control group (89%) than in the lepirudin-treated patient group (77%). There was no association between the incidence of the combined endpoint and sex (female vs male, RR = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.46-1.22; P = .25), age (older than 65 vs younger than 65 years, RR = 1.07; 95% CI, 0.66-1.75; P = .78), or patient population (medical and others vs surgery, RR = 1.0; 95% CI, 0.61-1.65; P = ∼l.0).

Patient demographics and characteristics

| Characteristic . | Lepirudin (n = 113) . | Historical control (n = 91) . |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 41 (36%) | 32 (35%) |

| Female | 72 (64%) | 59 (65%) |

| Age (yrs) | ||

| Younger than 65 | 74 (65%) | 40 (44%) |

| 65 or older | 39 (35%) | 51 (56%) |

| Mean | 57 ± 15 | 64 ± 14 |

| Patient population | ||

| Internal medicine* | 56 (50%) | 27 (30%) |

| Orthopedic surgery | 23 (20%) | 34 (37%) |

| Traumatology | 12 (11%) | 19 (21%) |

| Cardiovascular surgery | 3 (3%) | 4 (4%) |

| Other surgical interventions | 13 (12%) | 6 (7%) |

| Other | 6 (5%) | 1 (1%) |

| TEC acquired during or after heparin/heparinoid therapy† | ||

| No. evaluable patients | 110 | 90 |

| No. with TEC | 85 (77.3%) | 80 (89%) |

| Type of TEC‡ | ||

| Venous-distal | 53 (62.4%) | 53 (66%) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 42 (49.4%) | 35 (44%) |

| Venous-proximal | 40 (47.8%) | 23 (29%) |

| Arterial-peripheral | 30 (35.3%) | 17 (21%) |

| Characteristic . | Lepirudin (n = 113) . | Historical control (n = 91) . |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 41 (36%) | 32 (35%) |

| Female | 72 (64%) | 59 (65%) |

| Age (yrs) | ||

| Younger than 65 | 74 (65%) | 40 (44%) |

| 65 or older | 39 (35%) | 51 (56%) |

| Mean | 57 ± 15 | 64 ± 14 |

| Patient population | ||

| Internal medicine* | 56 (50%) | 27 (30%) |

| Orthopedic surgery | 23 (20%) | 34 (37%) |

| Traumatology | 12 (11%) | 19 (21%) |

| Cardiovascular surgery | 3 (3%) | 4 (4%) |

| Other surgical interventions | 13 (12%) | 6 (7%) |

| Other | 6 (5%) | 1 (1%) |

| TEC acquired during or after heparin/heparinoid therapy† | ||

| No. evaluable patients | 110 | 90 |

| No. with TEC | 85 (77.3%) | 80 (89%) |

| Type of TEC‡ | ||

| Venous-distal | 53 (62.4%) | 53 (66%) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 42 (49.4%) | 35 (44%) |

| Venous-proximal | 40 (47.8%) | 23 (29%) |

| Arterial-peripheral | 30 (35.3%) | 17 (21%) |

Excluding patients with surgery.

All patients had ongoing TEC, but in 22.7% of the lepirudin-treated patients and in 11% of the historical control patients, TEC was the primary indication for heparin treatment.

Percentages refer to numbers of patients with TEC; patients might have had multiple TEC of multiple types.

HIT, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia; TEC, thromboembolic complication.

Efficacy

Outcomes during study periods.

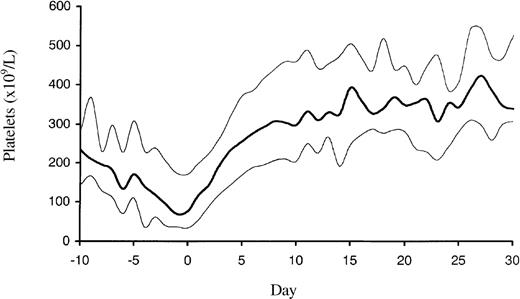

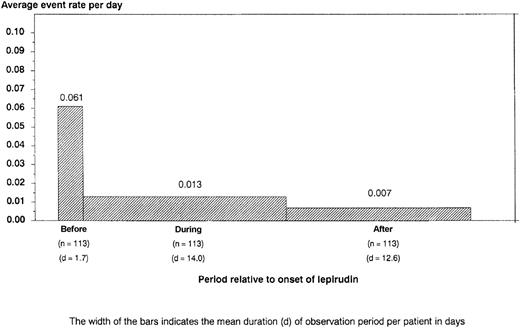

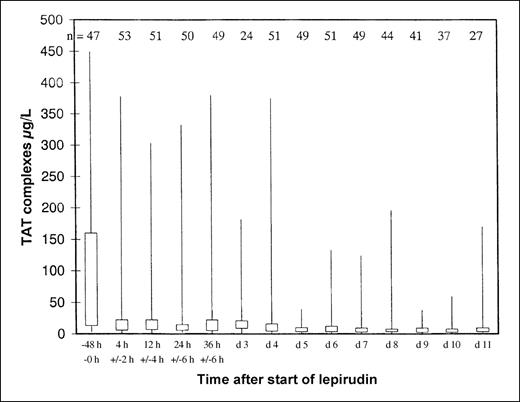

Overall, 105 patients were treated according to regimen A1 for a mean of 13.5 days (range, 0-104 days), and 8 patients were treated according to regimen A2 for a mean of 10.6 days (range, 1-29 days). Platelet counts normalized rapidly in most patients (Figure1). During the entire observation period, the primary endpoint occurred in 25 lepirudin-treated patients (22.1%; 95% CI, 14.5%-29.8%): 11 patients died (9.7%; 95% CI, 4.9%-16.8%), 7 patients underwent limb amputation (6.2%; 95% CI, 2.5%-12.3%), and 12 patients experienced a total of 23 new TEC (10.6%; 95% CI, 5.8%-18.3%). However, venous limb gangrene did not develop in any patient after the change to oral anticoagulation (phenprocoumon). The risk for a clinical event was highest from the time of diagnosis of HIT to the start of lepirudin treatment (mean, 1.7 days). The combined event rate per patient day during this pretreatment period was 6.1%. It decreased to 1.3% during lepirudin treatment and to 0.7% in the posttreatment period (Figure2), primarily because of a risk reduction for new TEC (pretreatment, 6.1%; treatment period, 0.6%; posttreatment, 0.2% per patient day). This was paralleled by a rapid decrease in elevated thrombin–antithrombin levels from a pretreatment median of 43.9 μg/L ± 118.3 to a median 9.18 μg/L ± 71.7 at 24 ± 6 hours and to a median 4.9 μg/L ± 27.8 on day 7 (Figure3).

Platelet count profile of the 113 patients with HIT and ongoing thrombosis.

The profile shows a decrease of platelet counts with a nadir at the time of HIT diagnosis and a rapid normalization to supranormal platelet count levels after the cessation of heparin therapy and start of lepirudin (day 0). The median (bold line) and the 25% and 75% quartiles are given.

Platelet count profile of the 113 patients with HIT and ongoing thrombosis.

The profile shows a decrease of platelet counts with a nadir at the time of HIT diagnosis and a rapid normalization to supranormal platelet count levels after the cessation of heparin therapy and start of lepirudin (day 0). The median (bold line) and the 25% and 75% quartiles are given.

Average rate of adverse events (death, limb amputation, and new TEC) per patient day by study interval.

Bar width indicates the mean duration of the observation period per patient in days (d). This shows that patients are at highest risk for new complications from the time of diagnosis of HIT to the start of alternative anticoagulation therapy; cessation of heparin therapy alone is insufficient to prevent further thromboembolism; if there is a strong clinical suspicion of HIT, the patient should be anticoagulated with an alternative drug immediately.

Average rate of adverse events (death, limb amputation, and new TEC) per patient day by study interval.

Bar width indicates the mean duration of the observation period per patient in days (d). This shows that patients are at highest risk for new complications from the time of diagnosis of HIT to the start of alternative anticoagulation therapy; cessation of heparin therapy alone is insufficient to prevent further thromboembolism; if there is a strong clinical suspicion of HIT, the patient should be anticoagulated with an alternative drug immediately.

Decrease of elevated thrombin–antithrombin (TAT) levels during lepirudin treatment.

Thrombin–antithrombin (TAT) levels as measured by ELISA were highly elevated in patients with acute HIT and ongoing thromboembolic complications (normal range, 1.0-4.1 μg/L), but normalized rapidly after the start of lepirudin treatment. The 25% and 75% quartiles and minimum and maximum values are given at the baseline (ie, up to 48 hours before the start of lepirudin), at 4 hours ± 2 hours, 12 hours ± 2 hours, 24 hours ± 6 hours, 36 hours ± 6 hours after the start of lepirudin, and then daily. Numbers of investigated patients at each time point are given at the top of the figure. The low number of patients at day 3 results from an overlap because 36 hours ± 6 hours was day 3 in those patients for whom treatment started late, at day 1, and values were counted only once. The small peak at day 3 was induced by patients receiving concomitant thrombolysis and, therefore, a reduced lepirudin dosage. These data underscore the prominent role of thrombin in acute HIT, provide a rationale for the use of a direct thrombin inhibitor in these patients, and indicate that in acute HIT thrombin generation is highest until day 4 to 5.

Decrease of elevated thrombin–antithrombin (TAT) levels during lepirudin treatment.

Thrombin–antithrombin (TAT) levels as measured by ELISA were highly elevated in patients with acute HIT and ongoing thromboembolic complications (normal range, 1.0-4.1 μg/L), but normalized rapidly after the start of lepirudin treatment. The 25% and 75% quartiles and minimum and maximum values are given at the baseline (ie, up to 48 hours before the start of lepirudin), at 4 hours ± 2 hours, 12 hours ± 2 hours, 24 hours ± 6 hours, 36 hours ± 6 hours after the start of lepirudin, and then daily. Numbers of investigated patients at each time point are given at the top of the figure. The low number of patients at day 3 results from an overlap because 36 hours ± 6 hours was day 3 in those patients for whom treatment started late, at day 1, and values were counted only once. The small peak at day 3 was induced by patients receiving concomitant thrombolysis and, therefore, a reduced lepirudin dosage. These data underscore the prominent role of thrombin in acute HIT, provide a rationale for the use of a direct thrombin inhibitor in these patients, and indicate that in acute HIT thrombin generation is highest until day 4 to 5.

Comparison with the historical control group.

In the historical control group, 75 patients qualified for comparison. Fourteen patients were excluded because of incomplete treatment data, and 2 patients were excluded because of incomplete time-to-event data. Patients were treated with danaparoid (n = 24), phenprocoumon (n = 21), others (n = 30; low-molecular-weight heparin, no anticoagulation, acetyl salicylic acid, thrombolysis).

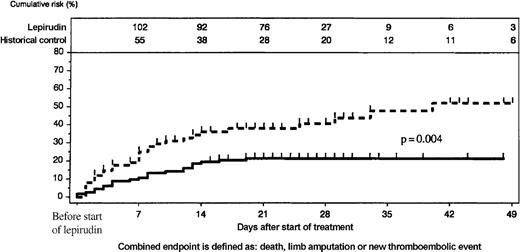

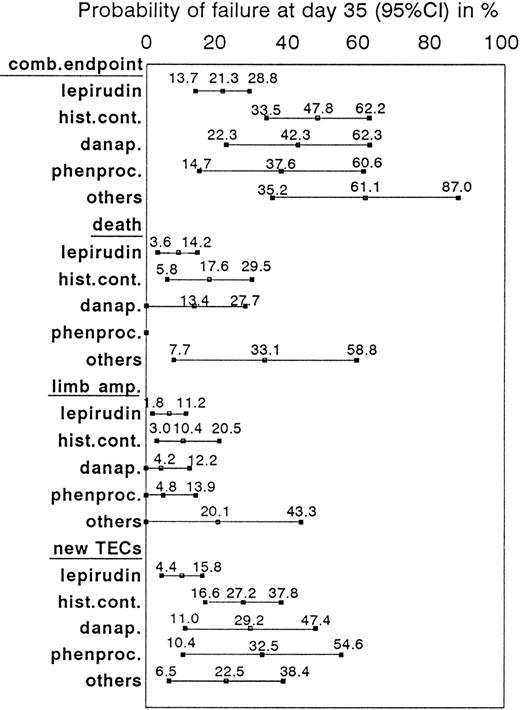

When outcomes between the start of active treatment and the end of the observation period were compared, lepirudin-treated patients had consistently lower incidences of the combined endpoint than the historical control group (P = .004, log-rank test; Figure4). This resulted primarily from a reduction of new TEC (at day 35: 10.1% [95% CI, 4.4%-15.8%] vs 27.2% [95% CI, 16.6%-37.8%]; P = .005, log-rank test). Cumulative incidences of death (day 35: 8.9% vs 17.6%) and limb amputation (day 35: 6.5% vs 10.4%) were nominally lower in the lepirudin group than in the historical control group, but the differences did not reach statistical significance (Figure5). At least 1 patient in the historical control group lost his leg because of venous limb gangrene when heparin treatment was discontinued and he received phenprocoumon without overlapping parenteral anticoagulation.

Comparison of lepirudin-treated patients and historical control group.

Cumulative incidence of events (new TEC, limb amputation, and death) was higher in the historical control group (scattered line) than in the lepirudin group (solid line); P = .004. The number of patients at risk is given at the top of the figure.

Comparison of lepirudin-treated patients and historical control group.

Cumulative incidence of events (new TEC, limb amputation, and death) was higher in the historical control group (scattered line) than in the lepirudin group (solid line); P = .004. The number of patients at risk is given at the top of the figure.

Description of combined and single endpoints in HIT patients treated with lepirudin, or danapariod, or phenprocoumon, or other treatments.

Incidences of the combined and single endpoints of death, limb amputation, and new TEC at day 35 are given in percentages and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) for lepirudin-treated patients (n = 113) and historical control patients (total, n = 75; danaparoid, n = 24; phenprocoumon, n = 21; others, n = 30).

Description of combined and single endpoints in HIT patients treated with lepirudin, or danapariod, or phenprocoumon, or other treatments.

Incidences of the combined and single endpoints of death, limb amputation, and new TEC at day 35 are given in percentages and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) for lepirudin-treated patients (n = 113) and historical control patients (total, n = 75; danaparoid, n = 24; phenprocoumon, n = 21; others, n = 30).

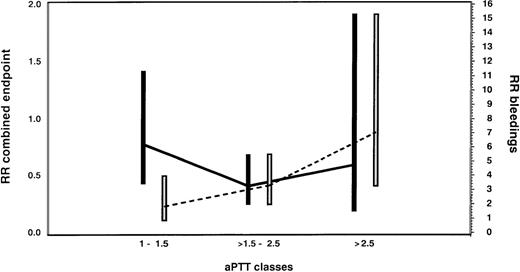

Correlation between aPTT ratios and efficacy.

Medium aPTT ratios (1.5-2.5) were associated with a clinically and statistically significant reduction in the incidence of the combined endpoint compared with the historical control group (RR = 0.42; 95% CI, 0.22-0.80; P = .009). Low aPTT ratios (1.0 to 1.5) were associated with an insignificant effect (RR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.38-1.94;P = .72), whereas high aPTT ratios (greater than 2.5) demonstrated no additional improvement compared with medium aPTT ratios (RR = 0.70; 95% CI, 0.21-2.32; P = .56; Figure6).

Assessment of the optimal therapeutic range of lepirudin in HIT patients with thrombosis.

Risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals for the combined endpoint of new TEC, limb amputation, and death (black bars and solid line) and for bleeding complications (white bars and dotted line) are given for the lepirudin-treated patients according to aPTT classes in comparison with the historical control population. In this Cox proportional hazards model, the aPTT ratio was considered a time-dependent covariate. Medium aPTT ratios (1.5-2.5) were associated with a clinically and statistically significant reduction in the incidence of the combined endpoint compared with the historical control group (RR = 0.42; 95% CI, 0.22-0.80; P = .009). Low aPTT ratios (1.0-1.5) were associated with an insignificant effect (RR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.38-1.94; P = .72), whereas high aPTT ratios (greater than 2.5) demonstrated no additional improvement compared with medium aPTT ratios (RR = 0.70; 95% CI, 0.21-2.32; P = .56). However, there was a marked increase in bleedings with high aPTT ratios (RR = 6.03; 95% CI, 2.34-15.54; P = .0002). We, therefore, consider aPTT ratios of 1.5 to 2.5 as the therapeutic window in patients with HIT and acute thrombosis.

Assessment of the optimal therapeutic range of lepirudin in HIT patients with thrombosis.

Risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals for the combined endpoint of new TEC, limb amputation, and death (black bars and solid line) and for bleeding complications (white bars and dotted line) are given for the lepirudin-treated patients according to aPTT classes in comparison with the historical control population. In this Cox proportional hazards model, the aPTT ratio was considered a time-dependent covariate. Medium aPTT ratios (1.5-2.5) were associated with a clinically and statistically significant reduction in the incidence of the combined endpoint compared with the historical control group (RR = 0.42; 95% CI, 0.22-0.80; P = .009). Low aPTT ratios (1.0-1.5) were associated with an insignificant effect (RR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.38-1.94; P = .72), whereas high aPTT ratios (greater than 2.5) demonstrated no additional improvement compared with medium aPTT ratios (RR = 0.70; 95% CI, 0.21-2.32; P = .56). However, there was a marked increase in bleedings with high aPTT ratios (RR = 6.03; 95% CI, 2.34-15.54; P = .0002). We, therefore, consider aPTT ratios of 1.5 to 2.5 as the therapeutic window in patients with HIT and acute thrombosis.

Effect of thrombolytics, aspirin, and coumarin.

At some point during the study, but not necessarily in conjunction with lepirudin, 29 patients received aspirin, 93 patients received coumarin, and 27 patients received thrombolytics; for 7 patients, this information was missing. Comedication with thrombolytics (RR = 0.38; 95% CI, 0.14-1.05; P = .06) or coumarin (RR = 0.61; 95% CI, 0.36-1.02; P = .06) showed a trend toward a reduction of the combined endpoint, whereas coadministration with aspirin was associated with a trend toward higher event rates (RR = 1.75; 95% CI, 0.95-3.25; P = .08).

After the initiation of lepirudin therapy, the Quick value decreased from 74.3% (±24.8% SD) to 55.6% (±19.8% SD); P = .0005. More important, at the end of lepirudin treatment, Quick values did not change if lepirudin was discontinued (37.0% ± 15.2% vs 35.3% ± 15.5%; P = .31).

Safety

Bleeding events.

The cumulative incidence of bleeding was significantly higher in the lepirudin-treated group than in the historical control group (at 35 days: 42.0% [95% CI, 28.9%-55.0%] vs 23.6% [95% CI, 9.3%-37.8%]; P = .001). Similarly, more lepirudin-treated patients than historical control patients experienced bleeding that required transfusion (at 35 days: 18.8% [95% CI, 11.6%-26.1%] vs 7.1% [95% CI, 1.1%-13.1%]; P = .02). No fatal or intracranial bleed occurred in patients treated with lepirudin (2 intracranial bleeds occurred in the historical control group).

Correlation of aPTT ratios and bleeding events.

With low aPTT ratios, the risk for bleeding in lepirudin-treated patients was not significantly increased in comparison with historical control patients (RR = 1.57; 95% CI, 0.52-4.72; P = .42). However, there was a marked increase with medium aPTT ratios (RR = 3.21; 95% CI, 1.72-6.02; P = .0003) and particularly with high aPTT ratios (RR = 6.03; 95% CI, 2.34-15.54; P = .0002; Figure6). None of the covariates assessed were significantly associated with an increased bleeding risk: sex (female vs male, RR = 1.06; 95% CI, 0.61-1.85; P = .83); age (older than 65 vs younger than 65 years, RR = 1.29; 95% CI, 0.74-2.26; P = .37); patient population (medical and others vs surgery, RR = 1.58; 95% CI, 0.91-2.73; P = .10); aspirin treatment (RR = 1.2; 95% CI, 0.56-2.55; P = .65); coumarin treatment (RR = 0.72; 95% CI, 0.40-1.30; P = .28); and thrombolytic treatment (RR = 1.77; 95% CI, 0.86-3.65; P = .20).

Discussion

This meta-analysis of data from 2 prospective clinical studies presents the largest population of patients with HIT and thromboembolic complications treated with lepirudin. It provides the rationale for new or extended recommendations for lepirudin in the treatment of patients with HIT and TEC, and it illustrates important concepts in the treatment of HIT in general.

The reduction in the combined endpoint of death, limb amputation, and new TEC in lepirudin-treated patients compared with the historical control population (Figure 4) indicates that lepirudin offers clinical benefits for patients with HIT and ongoing thrombosis. By 35 days, there was a 27% relative risk reduction for the combined endpoint, with trends in the same direction for all individual endpoints (death, 9%; limb amputation, 4%; new TEC, 17%). Because this meta-analysis is based on historically controlled studies, a bias cannot be excluded, and results must be interpreted with caution; nevertheless, the outcomes of lepirudin-treated patients in these studies were far better than those reported for patients with HIT in other studies.23 24 The number of danaparoid-treated patients (n = 24) in the historical control group is too small to allow any firm conclusion regarding its comparability with lepirudin.

Prospectively assessed thrombin–antithrombin complexes clearly show that HIT is associated with the massive generation of thrombin, as has been suggested recently based on retrospective data.25 In conjunction with the clinical findings of the meta-analysis, this corroborates that heparin cessation alone is insufficient to prevent further thromboembolism in acute HIT. Of the 41 clinical outcome events reported during the study period, 14 (34.1%) occurred during the pretreatment period, and the combined event rate per patient day was substantially higher during the pretreatment interval (6.1%) than during the treatment (1.3%) or posttreatment period (0.7%; Figure 2). Differences in the combined event rates were primarily accounted for by differences in the incidences of new TEC. Thus, if there is a strong suspicion of HIT, a patient with a recent thrombosis should immediately be treated with an anticoagulant other than heparin. Awaiting laboratory confirmation of HIT before alternative anticoagulation therapy is started would cause a significant delay for most patients and substantially enhance the risk for the patient.

This study compares for the first time different anticoagulation intensities in patients with HIT using the aPTT ratio. Based on our results, we consider the aPTT ratio to have a significant impact on the outcome of patients with HIT and thromboembolic complications. Low aPTT ratios (1.0-1.5) were clearly subtherapeutic and had minimal effects on clinical events and bleeding. In contrast, medium aPTT ratios (1.5 to 2.5) were associated with a pronounced reduction in the combined endpoint rate (RR = 0.42) and a moderately increased risk for bleeding (RR = 3.21). This increased risk for bleeding appears to be clinically acceptable because it is outweighed by the prevention of serious clinical events, particularly new TEC. Higher aPTT ratios did not further reduce the combined endpoint rates, but they once more doubled the risk for bleeding (RR = 6.03). Thus, the aPTT ratio of greater than 1.5 to 2.5 is the recommended target range (when actin FS or neothromtin reagents are used, the ratio should be greater than 1.5-3.0).

However, even with this optimal aPTT ratio, bleeding complications were more frequent in lepirudin-treated patients than in the historical control population. This may reflect the limitations of the aPTT as a monitoring tool for lepirudin treatment. Although the aPTT method of monitoring anticoagulation is readily available and easy to use, it may not be optimal.26,27 At higher hirudin concentrations, causing an aPTT longer than 70 seconds, the correlation between aPTT and free hirudin plasma levels is relatively poor.27Pötzsch et al27 have further shown that if high hirudin concentrations are clinically indicated (eg, during cardiopulmonary bypass surgery), monitoring by ecarin clotting time instead of the aPTT may be beneficial. It appears that lepirudin has a narrow therapeutic window and a relatively high bleeding risk even when given in clinically relevant doses in patients with HIT. Even so, the drug remains an important therapeutic agent given the dangerous clinical course of HIT and the apparent low risk for fatal hemorrhage related to lepirudin use. However, patients should be informed about the potential risk for bleeding before anticoagulation therapy is changed to lepirudin therapy.

Various covariates such as sex, age, and patient population (medical and others vs surgery) had no obvious impact on patient outcome. Regarding comedication, thrombolytics may be beneficial in certain patient groups, whereas concomitant therapy with aspirin does not appear to be. However, measuring concomitant drug effects was not part of the prospective study design of either trial, so these findings should be interpreted cautiously. Specifically, the need for aspirin could indicate that patients receiving aspirin may have a higher risk for further complications because of other risk factors for arterial embolism. There was no evidence to suggest that concomitant treatment with thrombolytics or aspirin was associated with a significant increase in the risk for bleeding complications. Therefore, until further information is available, it seems acceptable to use lepirudin with these medications if they are clinically indicated after a careful individual risk/benefit assessment.

Most patients with HIT and thrombosis require prolonged anticoagulation, usually with oral anticoagulants such as phenprocoumon or warfarin. Of the lepirudin-treated patients, 93 were changed to phenprocoumon therapy for long-term anticoagulation. Venous limb gangrene did not develop in any of these patients. In contrast, at least 1 of 21 historical control patients treated with phenprocoumon lost a leg only because of venous gangrene. This indicates that lepirudin allows a safe change to oral anticoagulants in patients with HIT and further supports the concept of Warkentin et al25that oral anticoagulants should not be given to patients with HIT unless parenteral anticoagulation therapy is sufficient.

At the start of treatment, lepirudin has an impact on the clotting parameters for the extrinsic coagulation pathway (decrease of Quick value or increase of the INR). Because of insufficient standardization of the Quick value, however, we cannot give an exact INR range. Whereas a change in the Quick value at the start of treatment with lepirudin has only minor clinical relevance, the impact of lepirudin on the monitoring parameter may be crucial once the therapeutic range for oral anticoagulation is reached and lepirudin should be stopped. Because we did not find evidence that the cessation of lepirudin causes a change of the monitoring values for oral anticoagulants, patients seem to remain in the therapeutic window.

This meta-analysis gives further evidence that lepirudin is effective for the treatment of patients with HIT with ongoing thrombosis and that it has an acceptable safety profile at aPTT ratios of greater than 1.5 to 2.5. It underscores the necessity of an early start of alternative anticoagulation once the diagnosis of HIT is made, and it provides evidence that oral anticoagulation can be started safely without the risk of inducing venous limb gangrene during the concomitant application of lepirudin.

Acknowledgment

We thank Mrs Uta Alpen for her secretarial assistance.

Supported by Aventis Pharma and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft GR 1096/2-3.

Reprints:Andreas Greinacher, Institute for Immunology and Transfusion Medicine, Ernst–Moritz–Arndt University, Sauerbruchstrasse/Diagnostikzentrum, 17487 Greifswald, Germany; e-mail:greinach@mail.uni-greifswald.de.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal