Abstract

Extracorporeal exposure of peripheral blood mononuclear cells to the photosensitizing agent 8-methoxypsoralen and UV-A radiation has been shown to be effective in the treatment of selected diseases mediated by T cells, rejection after solid organ transplantation, and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). We present 21 patients with a median age of 38 years who developed steroid-refractory acute GVHD grades II to IV after stem cell grafting from sibling or unrelated donors and were referred to extracorporeal photochemotherapy (ECP). Three months after initiation of ECP 60% of patients achieved a complete resolution of GVHD manifestations. Complete responses were obtained in 100% of patients with grade II, 67% of patients with grade III, and 12% of patients with grade IV acute GVHD. Three months after start of ECP complete responses were achieved in 60% of patients with cutaneous, 67% with liver, and none with gut involvement. Adverse events observed during ECP included a decrease in peripheral blood cell counts in the early phase after stem cell transplantation (SCT). Currently, 57% of patients are alive at a median observation time of 25 months after SCT. Probability of survival at 4 years after SCT is 91% in patients with complete response to ECP compared to 11% in patients not responding completely. Our findings suggest that ECP is an effective adjunct therapy for acute steroid-refractory GVHD with cutaneous and liver involvement. However, in patients with acute GVHD grade IV or gut involvement other therapeutic options are warranted.

Introduction

Acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a major complication of allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT) that results in significant morbidity and mortality. Despite prophylaxis with cyclosporine (CSA) or methotrexate (MTX) or both, acute GVHD occurs in 30% to 50% of patients receiving transplants from HLA-identical sibling donors and in 50% to 80% of patients receiving transplants from HLA-matched unrelated donors.1-3 Acute GVHD is classified into 4 grades according to published criteria.4Long-term survival in patients developing severe acute GVHD has generally been less than 30%.5,6 Despite advances in the understanding of acute GVHD and its prophylaxis, little progress has been made in the primary treatment of established disease.7-9 Steroids constitute the main therapy, alone or in association with antithymocyte globulin (ATG), CSA, or monoclonal antibodies (mAb).8-10 Response and survival after acute GVHD depend on a number of variables, including patient clinical performance, infections, gastrointestinal bleeding, and pneumonitis, which often are associated with acute GVHD.8 9 Patients unresponsive to corticosteroids are at high risk of death due to infections.

Extracorporeal photochemotherapy (ECP) is currently being used for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, selected autoimmune diseases, and rejection after solid organ transplantation.11,12 ECP is based on the infusion of autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells collected by apheresis, incubated with the photoactivable drug 8-methoxypsoralen (8-MOP) and UV-A irradiation. Recently, ECP has shown considerable efficacy in treatment of steroid-refractory chronic GVHD.13 14

So far, results of ECP treatment have been reported in only a small number of patients with steroid-refractory acute GVHD including 6 previously treated patients at our institution.13-18 Here, we present results of a prospective pilot study with a larger number of patients with steroid-refractory acute GVHD grades II to IV treated with ECP.

Patients and methods

Patients

The pretransplant characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. Data on the first 6 patients have previously been reported.13 Stem cell donors were HLA-identical siblings in 5 patients, HLA-identical unrelated donors in 12 patients, 1-antigen mismatched sibling donor in 1 patient, and 1-antigen mismatched unrelated donors in 3 patients. All patients had central venous catheters implanted on the day of admission. Catheters were removed between days 100 and 150 after SCT. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. Data were analyzed as of January 31, 2000.

Overall patient characteristics

| No. of patients | 21 |

| Median age (y) | 38 |

| Range | 27-55 |

| Male/female | 10/11 |

| Diagnosis | |

| AML | 3 |

| ALL | 5 |

| CML | 10 |

| Others | 3 |

| Conditioning regimen | |

| CY/fTBI | 19 |

| BU/CY | 2 |

| GVHD prophylaxis | |

| CSA/MTX | 20 |

| CSA | 1 |

| SC donors | |

| Serologic and LBT match | 17 |

| Serologic class I mismatch | 4 |

| Related/unrelated | 6/15 |

| SC source | |

| BM | 19 |

| PBSC | 2 |

| No. of patients | 21 |

| Median age (y) | 38 |

| Range | 27-55 |

| Male/female | 10/11 |

| Diagnosis | |

| AML | 3 |

| ALL | 5 |

| CML | 10 |

| Others | 3 |

| Conditioning regimen | |

| CY/fTBI | 19 |

| BU/CY | 2 |

| GVHD prophylaxis | |

| CSA/MTX | 20 |

| CSA | 1 |

| SC donors | |

| Serologic and LBT match | 17 |

| Serologic class I mismatch | 4 |

| Related/unrelated | 6/15 |

| SC source | |

| BM | 19 |

| PBSC | 2 |

AML indicates acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; CY, cyclophosphamide; fTBI, fractionated total body irradiation; BU, busulfan; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; CSA, cyclosporine; MTX, methotrexate; SC, stem cell; LBT, ligation-based typing of class II; BM, bone marrow; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cells.

Evaluation criteria

From 1996 on, patients with clinicopathologic diagnosis of acute GVHD refractory to steroid treatment were treated with ECP. Due to the limited capacity for ECP at our institution, not all consecutive patients with severe steroid-refractory acute GVHD could receive ECP. Patients referred for ECP had baseline evaluations, including a history and physical examination, complete blood count with differential, and complete chemistry panel.

The clinical diagnosis of GVHD was confirmed by histopathology of the skin in all patients and, if indicated, liver or mucous membrane biopsies were clinically graded as 0 through IV for acute GVHD by the criteria reported4 and as none, limited, or extensive for chronic GVHD.19 Complete organ responses of acute GVHD were defined as resolution of skin, liver, or gut manifestations. Partial responses were defined as a more than 50% response in organ involvement, but less than a complete response. No change was defined as stable organ involvement, despite the tapering of other immunosuppressive agents by at least 50% of the dosage. No response referred to progressive worsening of acute GVHD and the inability to taper other medications. Steroid-refractory acute GVHD was defined as either no response of organ manifestations or inability to taper steroids without increased GVHD activity when steroids were given at a dose of at least 2 mg/kg body weight for at least 7 days.

ECP and treatment protocol

The ECP procedure was performed using the UVAR photopheresis system (Therakos, West Chester, PA), as described.13 The mean treatment time for the photopheresis procedure was 3.5 hours. Preferentially, peripheral vein catheters were used. ECP was initiated in patients with steroid-refractory acute GVHD when the white blood cell count was more than 1 × 109/L and no acute infections were observed. Patients were treated on 2 consecutive days (one cycle) at 1- to 2-week intervals until improvement and thereafter every 2 to 4 weeks until maximal response. Then, ECP was tapered on an individual basis. All adverse effects obtained during the treatments were recorded. Informed consent was obtained from the patients, and the use of ECP was approved by the medical ethics committee of the University of Vienna.

Skin biopsy

Punch biopsies (4 mm) were performed in all patients at onset of cutaneous GVHD, before ECP, and after improvement or resolution of GVHD on ECP. Skin biopsies were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Sections were evaluated by light microscopy. The histopathologic diagnosis of acute cutaneous GVHD grades I to IV was based on the criteria and grading as suggested by Lerner and colleagues.20

Statistical methods

Survival, incidence of transplant-related mortality, and relapse rates were estimated using the method of Kaplan and Meier. Comparisons were based on the generalized Wilcoxon test and the log-rank test.

Results

All patients had restoration of normal hematopoiesis as indicated by rising blood cell counts and return of marrow cellularity within 4 weeks of stem cell grafting.

Acute GVHD and response to ECP

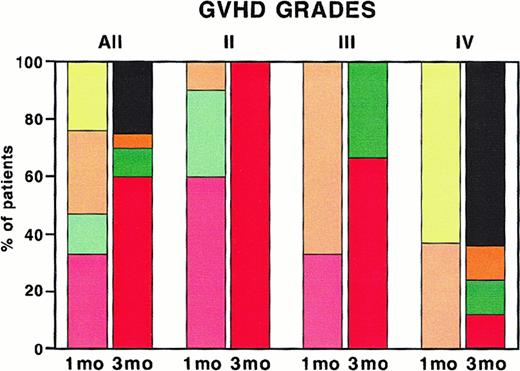

All patients experienced acute GVHD grades II to IV at a median of 19 days after SCT and did not respond to CSA and corticosteroids administered for a median of 21 days as shown in Table2. All patients had histologically proven cutaneous GVHD grades III to IV, 12 patients had liver involvement (including 2 patients with histologic confirmation) grades I to IV, and 4 patients had gut manifestations (including 3 patients with histologic confirmation) of GVHD grades II or III. One and 3 months after initiation of ECP 33% and 60% of patients, respectively, achieved a complete resolution of GVHD manifestations as shown in Figure1. The maximal response to ECP was achieved after a median of 4 cycles (range, 1-13 cycles) or 2 months (range, 0.5-6 months) of therapy.

Results of ECP in patients with acute steroid-refractory GVHD

| Pt. no. . | Acute GVHD . | Steroids before ECP . | Interval SCT-ECP (d) . | Response to ECP . | Time off ECP (mo) . | Outcome . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade . | Onset (d) . | Max dose (mg) . | Duration (d) . | Skin . | Liver . | Gut . | ||||

| 1 | III | 13 | 2 | 32 | 45 | CR | CR | NA | 16 | Alive, CR |

| 2 | III | 12 | 4 | 20 | 36 | CR | CR | NA | 19 | Alive, chron extens |

| 3 | IV | 13 | 10 | 15 | 34 | PR | NR | NR | NA | Death (sepsis) |

| 4 | II | 13 | 2 | 29 | 42 | CR | CR | NA | NA | Death (relapse) |

| 5 | IV | 13 | 10 | 29 | 42 | PR | NA | NR | NA | Death (sepsis) |

| 6 | IV | 27 | 2 | 17 | 44 | NC | CR | NA | NA | Death (sepsis) |

| 7 | IV | 15 | 10 | 22 | 37 | CR | CR | NA | NA | Death (relapse) |

| 8 | II | 21 | 2 | 49 | 70 | CR | NA | NA | 41 | Alive, CR |

| 9 | II | 14 | 4 | 23 | 37 | CR | NA | NA | 24 | Alive, CR |

| 10 | II | 30 | 2 | 26 | 57 | CR | NA | NA | NA | Death (relapse) |

| 11 | II | 26 | 2 | 9 | 44 | CR | NA | NA | 14 | Alive, chron lim |

| 12 | II | 13 | 2 | 23 | 36 | CR | NA | NA | 15 | Alive, CR |

| 13 | II | 18 | 3 | 21 | 48 | CR | NA | NA | 25 | Alive, CR |

| 14 | IV | 25 | 10 | 9 | 34 | PR | CR | NA | 9 | Alive, chron extens |

| 15 | III | 18 | 2 | 24 | 42 | CR | CR | NA | 16 | Alive, CR |

| 16 | IV | 14 | 5 | 23 | 38 | PR | NR | NR | NA | Death (sepsis) |

| 17 | II | 33 | 2 | 9 | 42 | CR | CR | NA | 5 | Alive, CR |

| 18 | II | 19 | 2 | 14 | 42 | CR | NA | NA | 1 | Alive, CR |

| 19 | IV | 17 | 2.5 | 20 | 37 | NC | NC | NA | NA | Death (H zost) |

| 20 | IV | 10 | 2 | 10 | 20 | NC | NR | NR | NA | Death (MOF) |

| 21 | II | 32 | 2 | 9 | 42 | NC | NA | NA | NA* | Alive, NC |

| Pt. no. . | Acute GVHD . | Steroids before ECP . | Interval SCT-ECP (d) . | Response to ECP . | Time off ECP (mo) . | Outcome . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade . | Onset (d) . | Max dose (mg) . | Duration (d) . | Skin . | Liver . | Gut . | ||||

| 1 | III | 13 | 2 | 32 | 45 | CR | CR | NA | 16 | Alive, CR |

| 2 | III | 12 | 4 | 20 | 36 | CR | CR | NA | 19 | Alive, chron extens |

| 3 | IV | 13 | 10 | 15 | 34 | PR | NR | NR | NA | Death (sepsis) |

| 4 | II | 13 | 2 | 29 | 42 | CR | CR | NA | NA | Death (relapse) |

| 5 | IV | 13 | 10 | 29 | 42 | PR | NA | NR | NA | Death (sepsis) |

| 6 | IV | 27 | 2 | 17 | 44 | NC | CR | NA | NA | Death (sepsis) |

| 7 | IV | 15 | 10 | 22 | 37 | CR | CR | NA | NA | Death (relapse) |

| 8 | II | 21 | 2 | 49 | 70 | CR | NA | NA | 41 | Alive, CR |

| 9 | II | 14 | 4 | 23 | 37 | CR | NA | NA | 24 | Alive, CR |

| 10 | II | 30 | 2 | 26 | 57 | CR | NA | NA | NA | Death (relapse) |

| 11 | II | 26 | 2 | 9 | 44 | CR | NA | NA | 14 | Alive, chron lim |

| 12 | II | 13 | 2 | 23 | 36 | CR | NA | NA | 15 | Alive, CR |

| 13 | II | 18 | 3 | 21 | 48 | CR | NA | NA | 25 | Alive, CR |

| 14 | IV | 25 | 10 | 9 | 34 | PR | CR | NA | 9 | Alive, chron extens |

| 15 | III | 18 | 2 | 24 | 42 | CR | CR | NA | 16 | Alive, CR |

| 16 | IV | 14 | 5 | 23 | 38 | PR | NR | NR | NA | Death (sepsis) |

| 17 | II | 33 | 2 | 9 | 42 | CR | CR | NA | 5 | Alive, CR |

| 18 | II | 19 | 2 | 14 | 42 | CR | NA | NA | 1 | Alive, CR |

| 19 | IV | 17 | 2.5 | 20 | 37 | NC | NC | NA | NA | Death (H zost) |

| 20 | IV | 10 | 2 | 10 | 20 | NC | NR | NR | NA | Death (MOF) |

| 21 | II | 32 | 2 | 9 | 42 | NC | NA | NA | NA* | Alive, NC |

Max indicates maximal; chron, chronic; lim, limited; extens, extensive; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; NC, no change; NR, no response; MOF, multiorgan failure; H zost, herpes zoster infection; NA, not applicable.

Patient is currently under therapy.

Overall response of patients with acute steroid-refractory GVHD to ECP 1 month and 3 months after start of treatment.

Overall response of all patients (All) and, in addition, patients with acute GVHD grades II, III, and IV are presented. The left column shows response 1 month (mo) and the right column 3 months after start of ECP. Red and pale red, complete response; green and pale green, partial response; orange and pale orange, no change; yellow, no response; black, patients who were dead at 3 months.

Overall response of patients with acute steroid-refractory GVHD to ECP 1 month and 3 months after start of treatment.

Overall response of all patients (All) and, in addition, patients with acute GVHD grades II, III, and IV are presented. The left column shows response 1 month (mo) and the right column 3 months after start of ECP. Red and pale red, complete response; green and pale green, partial response; orange and pale orange, no change; yellow, no response; black, patients who were dead at 3 months.

Response rates of different grades of acute GVHD are shown in Figure 1. Complete responses were achieved in 9 of 9 patients (100%) with grade II acute GVHD 3 months after start of ECP. Two of 3 patients (67%) with grade III and 1 of 8 patients (12%) with grade IV acute GVHD had a complete response. In the latter group 5 of 8 patients (64%) died within 3 months after initiation of ECP.

Response rates of patients with cutaneous manifestations of acute GVHD are shown in Figure 2. Three months after initiation of ECP complete responses were observed in 12 of 20 evaluable patients (60%) with cutaneous involvement including 11 of 13 patients (84%) with grade III and 1 of 7 patients (14%) with grade IV GVHD. In one patient the follow-up is currently less than 3 months. Another patient with cutaneous GVHD achieved a complete response 6 months after start of ECP. Five of 20 patients (25%) including 1 of 13 patients (8%) with grade III and 4 of 7 patients (58%) with grade IV GVHD died within 3 months of start of ECP.

Response of patients with acute steroid-refractory cutaneous GVHD to ECP.

Response of all patients (All) and, in addition, patients with acute GVHD grades III and IV is presented. The left column shows response 1 month (mo) and the right column 3 months after start of ECP. Red and pale red, complete response; green and pale green, partial response; orange and pale orange, no change; yellow, no response; black, patients who were dead at 3 months.

Response of patients with acute steroid-refractory cutaneous GVHD to ECP.

Response of all patients (All) and, in addition, patients with acute GVHD grades III and IV is presented. The left column shows response 1 month (mo) and the right column 3 months after start of ECP. Red and pale red, complete response; green and pale green, partial response; orange and pale orange, no change; yellow, no response; black, patients who were dead at 3 months.

Patients with liver involvement due to acute GVHD and responding to ECP had a rapid normalization after a median of 3 weeks of therapy as shown in Figure 3. Eight of 12 patients (67%) with liver involvement experienced a complete resolution, documented in normalization of serum bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels after 3 months.

Response of patients with acute steroid-refractory GVHD and liver involvement to ECP.

Individual patients are listed (1-12) and different colors represent the various grades of acute GVHD according to Glucksberg. Arrows indicate ECP therapy.

Response of patients with acute steroid-refractory GVHD and liver involvement to ECP.

Individual patients are listed (1-12) and different colors represent the various grades of acute GVHD according to Glucksberg. Arrows indicate ECP therapy.

Six of 9 patients (67%) with both skin and liver involvement achieved a complete response with ECP. No responses to ECP were observed in patients with combined skin, liver, and gut involvement as shown in Table 2.

During ECP, steroid therapy could be discontinued in responding patients after a median of 53 days (range, 18-122 days). After termination of ECP, patients remained on CSA for 2 months, but the dosage was subsequently reduced and finally treatment was terminated.

Infections and adverse events

Six patients died during the study period, 5 from infections related to deteriorating GVHD (patient nos. 3, 5, 6, 16, and 19) and 1 from multiorgan failure and severe gastrointestinal bleeding (patient no. 20) related to gut GVHD. Probability of transplant-related mortality (TRM) projected at 4 years after SCT was 32% for the entire group. In patients achieving a complete response of acute steroid-refractory GVHD, the TRM was 0% compared to 75% in patients without complete response 3 months after ECP, respectively. These differences are highly significant (P = .001).

Adverse events observed during a total of 230 cycles (460 procedures) of ECP are shown in Table 3.

Adverse events during study period

| . | No. patients . | No. episodes (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Decrease in Hb ≥ 1 g/dL | 19 | 74 (16) |

| Renewed RBC transfusion requirement | 10 | 26 (6) |

| Drop of ANC to < 1.5 × 109/L | 17 | 40 (9) |

| Drop of ANC to < 1 × 109/L | 7 | 12 (3) |

| Drop of ANC to < 0.5 × 109/L | 5 | 5 (1) |

| Decrease of Plts ≥ 50% | 15 | 75 (16) |

| Drop of Plts to < 20 × 109/L | 5 | 8 (2) |

| Renewed Plts transfusion requirement | 7 | 20 (4) |

| Bacterial infections | ||

| Sepsis | 7 | 9 |

| Urinary tract | 2 | 2 |

| Sinusitis | 1 | 1 |

| Ileitis | 1 | 1 |

| Fever of unknown origin | 14 | 21 |

| Viral infections | ||

| CMV reactivation | 11 | 12 |

| Herpes simplex/zoster | 7 | 14 |

| Fungal infections | ||

| Sepsis | 1 | 2 |

| Stomatitis | 4 | 4 |

| Bleeding | 3 | 3 |

| . | No. patients . | No. episodes (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Decrease in Hb ≥ 1 g/dL | 19 | 74 (16) |

| Renewed RBC transfusion requirement | 10 | 26 (6) |

| Drop of ANC to < 1.5 × 109/L | 17 | 40 (9) |

| Drop of ANC to < 1 × 109/L | 7 | 12 (3) |

| Drop of ANC to < 0.5 × 109/L | 5 | 5 (1) |

| Decrease of Plts ≥ 50% | 15 | 75 (16) |

| Drop of Plts to < 20 × 109/L | 5 | 8 (2) |

| Renewed Plts transfusion requirement | 7 | 20 (4) |

| Bacterial infections | ||

| Sepsis | 7 | 9 |

| Urinary tract | 2 | 2 |

| Sinusitis | 1 | 1 |

| Ileitis | 1 | 1 |

| Fever of unknown origin | 14 | 21 |

| Viral infections | ||

| CMV reactivation | 11 | 12 |

| Herpes simplex/zoster | 7 | 14 |

| Fungal infections | ||

| Sepsis | 1 | 2 |

| Stomatitis | 4 | 4 |

| Bleeding | 3 | 3 |

Hb indicates hemoglobin; RBC, red blood cells; ANC, absolute neutrophil counts; Plts, platelets; CMV, cytomegalovirus.

Survival and long-term outcome

Three patients (no. 2, 8, and 11) developed chronic GVHD 5 to 28 months after SCT and 1.5 to 17 months after discontinuation of ECP. Another patient (no. 14) progressed into chronic extensive GVHD and requires combined immunosuppressive therapy.

As of January 31, 2000, 12 of 21 patients (57%) are alive a median of 25 months (range, 2-53 months) after SCT. Five patients are off immunosuppression and 3 during CSA taper with a Karnofsky performance score above 90%.

Probability of survival at 4 years after SCT is 53% for the entire group as shown in Figure 5. In patients achieving a complete response of acute steroid-refractory GVHD 6 months after initiation of ECP, probability of survival was 91% compared to 11% in patients without complete response of GVHD to ECP. These differences are statistically significant (P = .0001).

Kaplan-Meier probability of overall survival of patients with acute steroid-refractory GVHD.

Overall survival is shown for all patients (All) and patients achieving a complete response (CR) or no CR to ECP. The difference between the 2 groups is significant at P = .0001.

Kaplan-Meier probability of overall survival of patients with acute steroid-refractory GVHD.

Overall survival is shown for all patients (All) and patients achieving a complete response (CR) or no CR to ECP. The difference between the 2 groups is significant at P = .0001.

Discussion

At present, corticosteroids are the first-line therapy for severe acute GVHD, achieving response rates of 24% to 70%.5,8-10 In a recent study the increase of steroid dose to 10 to 20 mg/kg body weight did not improve overall response and survival of GVHD patients.21 Various second-line immunosuppressive options for these patients have been investigated.10,22-27 Using ATG in steroid-refractory acute GVHD, overall response rates of 30% to 40% have been observed.10,22,27 Recently, Przepiorka and coworkers28 observed complete response rates of 29% to 47% using daclizumab, a humanized anti-interleukin-2 receptor (IL-2R) α-chain antibody. With anti-CD2 mAbs complete response rates of 30% have been achieved in patients with steroid-refractory acute GVHD.23 29

In search of further therapeutic options for patients with steroid-refractory acute GVHD and based on our results achieved with ECP in selected patients with severe resistant chronic GVHD,13 ECP was investigated as a second-line treatment in 21 patients with acute GVHD not responding to steroids at a dose of at least 2 mg/kg body weight. Three months after initiation of ECP 60% of patients achieved a complete resolution of GVHD manifestations. The maximal response to ECP was achieved after a median of 2 months. High complete response rates were achieved in patients with cutaneous (65%) and liver (67%) involvement and grades II (100%) to III (67%) of acute steroid-refractory GVHD. These results compare favorably with the ones achieved with mAbs against IL-2R or CD2.28,29 So far, only a few patients with acute GVHD treated with ECP have been reported.13-18 Whereas Sniecinski and colleagues15 and Besnier and coworkers16observed no response in a total of 7 patients, a complete resolution of grade III GVHD was achieved by Richter and associates17 in 1 patient. Dall'Amico and Zacchello18 documented improvements of acute GVHD in 3 of 4 pediatric patients during ECP.

Due to the rapid response to ECP, the dose of steroids could be reduced and discontinued after a median of 53 days in our responding patients. In view of the severe side effects of prolonged high-dose corticosteroid therapy the timely discontinuation of steroids is a major advantage for these patients.

The overall survival rate of 57% after a median observation time of 25 months after SCT in our study compares favorably with published results on second-line therapy of patients with acute steroid-refractory GVHD.25-29 A significantly higher probability of survival (91%) was seen in patients achieving a complete response 6 months after initiation of ECP compared to patients not responding (11%). Recently, failure of first-line therapy of acute GVHD has been reported as a significant factor in a multivariate analysis for poor 2-year survival with 10% survival rate in nonresponders and 54% in responders.30 The deaths observed in our study consisted of GVHD-associated infections and multiorgan failure and are similar to the ones reported in patients not responding to alternative GVHD therapies.

Extracorporeal photochemotherapy usually is tolerated excellently with very few side effects.14 In contrast to patients treated with ECP at our institution for chronic extensive GVHD, patients in the early phase after SCT had a marked decrease in hemoglobin levels, absolute neutrophil counts, and platelet counts after the first cycles of ECP. No increase in rate of infections during and after ECP compared with previously published results in these patients was seen in our study.5,8,9 21

The optimal duration and schedule of ECP treatment are still unclear. Our treatment schedule is based on clinical experience gained in patients with selected autoimmune diseases and chronic GVHD.11-13 Due to concerns about reactivation of GVHD activity after initial response, no abrupt discontinuation of ECP was performed and individual tapering of therapy occurred in our study. The results obtained support the use of ECP over a short treatment time because patients responding did so almost exclusively in the first 3 months, whereas little additional benefit could be obtained by continuation of ECP for a longer time. Whereas patients treated with mAbs had a hyporesponsive state of limited duration with high recurrence rates of GVHD after completion of therapy,23 29the majority of our patients had sustained resolution of GVHD activity.

The exact mechanisms by which ECP leads to the described responses in GVHD as well as other T-cell–mediated diseases have not been elucidated. ECP may be involved in augmenting the apoptotic process,31,32 which may lead to deletion of graft-reactive T cells. Another possibility is that the photoactivated 8-MOP may alter the idiotypes expressed by clones of autoreactive T cells of known or unknown specificity by up-regulation of class I expression.33 This might trigger the induction of specific autoregulatory T cells, most likely CD8+ T lymphocytes with suppressive or cytotoxic capabilities.34 Findings in the animal model support this concept.35 36 These hypotheses, however, warrant further investigation because most of the in vitro studies involving ECP, so far, have been performed in patients with neoplastic or autoimmune diseases.

In summary, our results demonstrate that ECP is an efficacious and well tolerated therapy for patients with acute steroid-refractory GVHD. Timely identification of nonresponding or incomplete responding patients allows early assignment to alternate immunosuppressive treatment. The early combination of ECP with other treatment strategies including mAbs could further improve survival of patients with gastrointestinal involvement or grade IV acute GVHD. However, randomized studies are mandatory to evaluate the impact of ECP on outcome of patients with GVHD.

Acknowledgments

We thank the dedicated nurses of our stem cell transplant program and the ECP unit, our fellows and house staff, the medical technicians, and the physicians who referred patients to our unit. We are indebted to the members of Geben fuer Leben–Knochenmarkspende Oesterreich for finding suitable unrelated donors for our patients.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Hildegard T. Greinix, AKH Wien, Klinik fuer Innere I, Knochenmarktransplantation, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, A-1090, Vienna, Austria; e-mail:hildegard.greinix@akh-wien.ac.at.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal