Abstract

The functional status of circulating human immunodeficiency (HIV)-specific CD8 T cells in chronically infected subjects was evaluated. By flow cytometry, only 5 of 7 subjects had detectable CD8 T cells that produced IFN-γ after stimulation with HIV-infected primary CD4 T cells. In 2 subjects, the frequency of IFN-γ–producing cells increased 4-fold when IL-2 was added to the culture medium; in another subject, IFN-γ–producing cells could be detected only after IL-2 was added. IFN-γ–producing cells ranged from 0.4% to 3% of CD8 T cells. Major histocompatibility complex–peptide tetramer staining, which identifies antigen-specific T cells irrespective of function, was used to evaluate the proportion of HIV-specific CD8 T cells that may be nonfunctional in vivo. CD8 T cells binding to tetramers complexed to HIV gag epitope SLYNTVATL and reverse transcriptase epitope YTAFTIPSI were identified in 9 of 15 and 5 of 12 HLA-A2–expressing seropositive subjects at frequencies of 0.1% to 1.1% and 0.1 to 0.7%, respectively. Freshly isolated tetramer-positive cells expressed a mixed pattern of memory and effector markers. On average, IFN-γ was produced by less than 25% of tetramer-positive CD8 T cells after stimulation with the relevant gag or reverse transcriptase peptide. In all subjects tested, freshly isolated CD8 T cells were not cytolytic against peptide-pulsed B lymphoblastoid cell line or primary HIV-infected CD4 T-cell targets. Exposure to IL-2 enhanced the cytotoxicity of CD8 T cells against primary HIV-infected CD4 targets in 2 of 2 subjects tested. These results suggest that a significant proportion of HIV-specific CD8 T cells may be functionally compromised in vivo and that some function can be restored by exposure to IL-2.

Introduction

Several studies suggest that CD8 T cells play a critical role in the control of virus replication in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Compelling evidence for their protective role comes from the temporal association of the viral-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response with the decline in plasma viremia in acute HIV infection and from the presence of a vigorous CTL response to HIV in long-term nonprogressors.1-6 Direct evidence for the protective role of CD8 T cells was recently provided in the closely related simian immunodeficiency virus model in Rhesus macaques, in which elimination of CD8 T cells resulted in a dramatic increase in viral load.7,8 However, despite the presence of HIV-specific CTL, viral production continues at a high level in most untreated infected subjects and inevitably leads to profound immunodeficiency and death in the absence of continued antiretroviral therapy. It is unclear why CD8 T cells provide only partial protection and are ultimately unable to prevent progression to AIDS. The ineffectiveness of the CTL response may at least partly be a consequence of viral evasion strategies, including viral-sequence mutation or nef-mediated down-modulation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I cell surface expression.9-17 Targeting of essential helper CD4 T cells by HIV may be another important cause for the progressive loss of CD8 T-cell function. Emerging data in the murine lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) model suggest that in the absence of adequate CD4 help, antiviral CD8 T cells persist indefinitely in a functionally anergic state.18 Loss of CD8 T-cell–mediated control of infection in the absence of CD4 T cells has also been demonstrated in mice infected with a gamma-herpes virus.19 We recently found that freshly isolated CD8 T lymphocytes from seropositive subjects are impaired in their ability to lyse HIV-presenting targets. Our studies suggest that the molecular basis for this loss of function of CD8 T cells may be linked to the down-modulation of CD3ζ, the key signaling molecule of the TcR complex.20 Signaling abnormalities after TcR engagement of CD8 T cells from HIV-infected donors have been reported in other studies.21 22

Most in vitro techniques for evaluating the functional status of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells necessitate the use of repeated antigenic challenge in an artificially enriched cytokine milieu. In vitro culture may introduce quantitative and qualitative biases that preclude assessment of the true extent of functional impairment of specific CD8 T cells in vivo. Further, repeated antigenic stimulation may result in the outgrowth of clones that are not truly representative of the circulating repertoire. More direct quantitation and functional characterization of circulating antigen-specific CD8 T cells have been greatly facilitated by the development of powerful new techniques, including highly sensitive tetramer staining and intracellular cytokine analysis of interferon (IFN)-γ production after a few hours of specific stimulation.23-27 With these advances, it is now possible to identify and characterize antigen-specific circulating CD8 T cells and to assess their functional capability without the need for prolonged in vitro expansion.

We used 2 approaches to look for possible functional impairment of HIV-specific CD8 T cells. One approach was to evaluate IFN-γ production of freshly isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in response to HIV-infected CD4 T cells. Uniform populations of HIV-infected stimulator cell targets were isolated by removing uninfected cells that continue to express cell surface CD4, as initially described by Ferrari et al.28 IFN-γ–producing cells could be easily identified by this method. The magnitude of the response varied between subjects. In some subjects, IFN-γ secretion in response to HIV-infected primary cells was greatly magnified or could be induced only after adding IL-2 to the cultures. Moreover, freshly isolated lymphocytes lysed primary HIV-infected CD4 T-cell targets only after in vitro exposure to IL-2. In the other approach, we used MHC-tetramer staining and flow cytometric analysis of HIV-specific IFN-γ production after stimulation by the cognate peptide to investigate the phenotypic and functional characteristics of circulating HIV-specific CD8 T cells in subjects at various stages of disease. Tetramers were used to stain T cells that recognized a well-characterized HLA-A2–restricted gag epitope, SLYNTVATL,29 and a novel A2-restricted reverse transcriptase (RT) epitope, YTAFTIPSI, that we recently described.30 In samples from most subjects, few tetramer-positive cells produced IFN-γ after stimulation with the cognate HIV peptide epitope. However, tetramer-positive cells could be induced to produce IFN-γ by short-term exposure to cytokines. Taken together, our data are consistent with the notion that circulating HIV-specific CD8 T cells are functionally compromised.

Materials and methods

Study population

This work was carried out on a cross-section of HLA-A2–positive HIV-infected subjects (n = 15, Table1). HLA-A2–expressing subjects were identified by standard serologic methods or by flow cytometric analysis with an HLA-A2.1–specific monoclonal antibody (mAb) PA2.1 (kind gift of Herman Eisen, Massachusetts Institute of Technology). The study was approved by the Center for Blood Research Institutional Review Committee. Blood was drawn after obtaining informed consent, and PBMC were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) density gradient centrifugation. Samples were either freshly obtained or cryopreserved using a programmed cell freezer (model 9000; Gordinier, Roseville, MI). Flow cytometry results obtained from thawed cells were comparable to those from freshly isolated cells.

Clinical characteristics of subjects

| Subject . | CDC disease stage* . | CD4 count (cells/mm3) . | Plasma viremia (copies/mL) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 136 | B2 | 410 | 4338 |

| 163 | A2 | 450 | < 500 |

| 215 | B3 | 150 | 46 322 |

| 216 | C3 | 50 | 5975 |

| 219 | A2 | 370 | 1512 |

| 237 | C2 | 260 | 3430 |

| 307 | B2 | 283 | 8633 |

| 348 | A1 | 680 | < 500 |

| 350 | A1 | 1005 | 70 |

| 351 | A1 | 571 | < 500 |

| 606 | A2 | 615 | < 50 |

| 701 | B3 | 71 | < 50 |

| 703 | A1 | 529 | < 50 |

| 704 | A1 | Unknown | < 50 |

| 705 | A2 | 650 | < 50 |

| Subject . | CDC disease stage* . | CD4 count (cells/mm3) . | Plasma viremia (copies/mL) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 136 | B2 | 410 | 4338 |

| 163 | A2 | 450 | < 500 |

| 215 | B3 | 150 | 46 322 |

| 216 | C3 | 50 | 5975 |

| 219 | A2 | 370 | 1512 |

| 237 | C2 | 260 | 3430 |

| 307 | B2 | 283 | 8633 |

| 348 | A1 | 680 | < 500 |

| 350 | A1 | 1005 | 70 |

| 351 | A1 | 571 | < 500 |

| 606 | A2 | 615 | < 50 |

| 701 | B3 | 71 | < 50 |

| 703 | A1 | 529 | < 50 |

| 704 | A1 | Unknown | < 50 |

| 705 | A2 | 650 | < 50 |

Defined by the lowest documented CD4 count.

Production of phycoerythrin-coupled tetrameric A2–HIV-gag and A2–HIV-RT peptide complexes

Bir A modified HLA-A2 heavy chain and β2 microglobulin were synthesized and purified from plasmids (obtained from M. Davis and D. C. Wiley, respectively) and refolded with the A2-restricted HIV-gag epitope peptide SLYNTVATL or the HIV-RT epitope peptide YTAFTIPSI. The complex was biotinylated using the Bir A enzyme as described.23 31 Tetramers were produced by mixing the biotinylated MHC-peptide complex with streptavidin-phycoerythrin (PE) at a molar ratio of 4:1. Before use, the tetrameric complexes were titrated to minimize background staining. The specificity of staining was confirmed for each tetrameric complex with peptide-specific CTL lines. In our hands, the sensitivity of detection of the assay above nonspecific staining was 0.1%.

Flow cytometry

For external staining, PBMC from A2-expressing seropositive subjects were resuspended in 500 μL FACS buffer and stained with 0.5 μg/mL streptavidin–PE-conjugated tetramer for 40 minutes at 4°C. The cells were washed and resuspended in FACS buffer, and aliquots of the suspension were stained with 2 μL of the following fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated mAbs: CD27, CD28, CD57, CD38, CD62L, HLA-DR, CD45RA, CD45RO, and Cy5-conjugated CD8 mAb or IgG-FITC and PE and Cy5 isotype-matched controls (Immunotech, Westbrook, ME). After incubation for 30 minutes at 4°C, cells were washed and resuspended in FACS buffer with 1% formaldehyde for analysis. For internal staining with bcl-2 (DAKO, Carpenteria, CA) and granzyme A-reactive mAb CB9,20 aliquots of tetramer-stained cells were resuspended in 50 μL Hanks balanced salt solution and permeabilized using the Caltag Laboratories (Burlingame, CA) Fix and Perm kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. Fixed cells were incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature with 2 μL of the respective antibodies conjugated to FITC, washed, and resuspended in 50 μL FACS buffer. The cells were then stained with CD8-Cy5 for 15 minutes and fixed in FACS buffer with 1% formaldehyde for flow cytometric analysis. All samples were analyzed on a FACScalibur with Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) on a lymphocyte-gated population.

Immunomagnetic enrichment of tetramer-positive population

PBMC, stained with PE-labeled HLA-A2 tetramers in sterile PBS with 2% fetal calf serum (FCS) for 40 minutes in the cold, were washed and incubated with α-PE Miltenyi beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) for another 15 minutes. The tetramer-PE cells that bound the beads were immunomagnetically selected on a Miltenyi column according to the manufacturer's instructions. An aliquot of the selected cells was costained with α-CD8 mAb conjugated to Cy5 to ascertain the levels of enrichment. Usually, more than 100-fold enrichment of the tetramer-positive population could be obtained by this method.

Intracellular cytokine staining

To enumerate the number of IFN-γ–producing cells within the tetramer population, 2 × 106 PBMC were stimulated with the relevant gag or pol peptide at a concentration of 5 μg/mL in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS for 8 hours at 37°C. Immunomagnetically selected tetramer-binding cells were stimulated with the peptide-pulsed autologous Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-transformed B lymphoblastoid cell line (BLCL). In some experiments PBMC were activated with 1 μg/mL phorbol-12 myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 0.25 μg/mL ionomycin (Sigma). In the last 4 hours of incubation, 10 μmol/L Brefeldin A (Sigma) was added to the cultures. At the end of the incubation, cells were washed and resuspended in FACS buffer and were stained with either gag or pol tetramer–PE on a rotator at 4°C for 40 minutes. Cells were then washed, fixed, permeabilized, and stained internally with FITC-conjugated IFN-γ mAb (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) followed by CD8-Cy5 mAb as described earlier. Simultaneously, control cultures without peptide stimulation were similarly stained. The proportion of tetramer-positive cells secreting IFN-γ in response to the cognate peptide was calculated as ([number of IFN-γ–positive CD8 T cells in cultures stimulated with peptide − number of IFN-γ–positive CD8 T cells in control cultures without peptide]/total number of tetramer-positive CD8 T cells in control cultures without peptide) × 100. Cells stained with isotype-matched FITC-MsIgG1 (R&D Systems) were used as negative controls.

HIV-infected primary CD4 T cells

To evaluate effector function of HIV-specific CD8 T cells ex vivo, we also used uniformly HIV-infected primary CD4+ T cells, generated as previously described,31 as target cells in cytotoxicity assays and as stimulator cells for IFN-γ production. Autologous CD4+ T cells were positively selected with CD4 Miltenyi beads and activated with phytohemagglutinin. Two days later, cells were infected with HIVIIIB virus at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1. Infected cells were selected by the method previously described,28,31 which is based on the down-modulation of CD4 on HIV-infected cells. After culture for 4 to 7 days, uninfected cells, which continue to express CD4, were removed by negative selection with CD4-Dynal beads per the manufacturer's instructions. HIV infection levels of the negatively enriched population were confirmed by flow cytometric analysis of p24 expression as described.31

Flow cytometric determination of IFN-γ–producing CD8 T-cell frequency in response to stimulation with HIV-infected CD4 T cells

CD8 T cells, positively selected with the Miltenyi Biotec Magnetic Separation MiniMACS system according to the manufacturer's protocol, were stimulated with uniformly HIV-infected CD4 blasts in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS at a ratio of 5:1 of CD8 T cells:infected CD4 T cells in the presence or absence of 600 IU/mL of IL-2. After 3 hours of incubation at 37°C, the cultures were treated with 10 μmol/L Brefeldin A overnight. Cells were resuspended in FACS buffer and stained for cell surface CD8 (Cy5) and CD69 (PE) and internally for IFN-γ–FITC as above.

Cytotoxicity assay

Log-phase BLCL target cells, produced as described,32 were labeled with 100 μCi of chromium 51 for an hour, washed 3 times in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FCS, and resuspended at 105/mL as described earlier.33,34 Labeled targets (104) were added to triplicate wells of U-bottom microtiter plates in the presence or absence of relevant HIV-gag and pol peptides. After incubating the target cells with the peptides for 1 hour at 37°C, effector cells suspended at various effector:target (E:T) ratios in 100 μL were added to the wells, and the plates were incubated at 37°C over CO2 for 6 hours. Supernatants (35 μL) were counted on a Top Count (Packard, Meriden, CT) microplate reader, and percentage specific cytotoxicity was calculated from the average cpm as ([average cpm − spontaneous release)/(total release − spontaneous release]) × 100. The spontaneous release for all experiments was within acceptable limits of less than 20%. Cytotoxicity against51Cr-labeled uniformly HIV-infected primary CD4 blasts and uninfected CD4 T-cell blast controls was evaluated as described.30 31

Results

Frequency of circulating HIV-specific CD8 T cells responding to stimulation with uniformly HIV-infected CD4 T cells

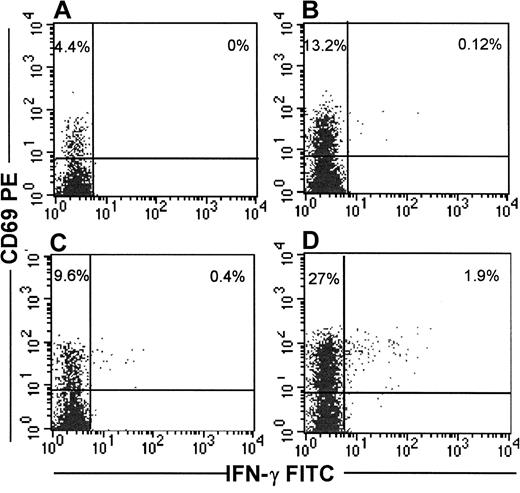

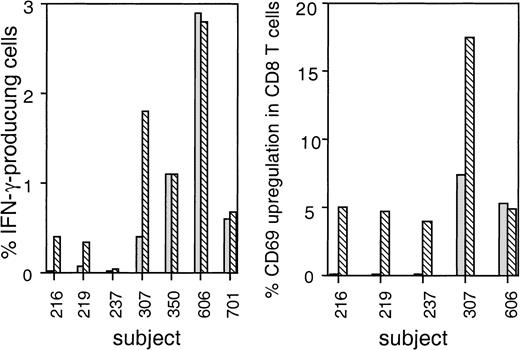

Detection of IFN-γ production after exposure of T cells to viral antigens has been shown to be an extremely sensitive method to identify antigen-specific T cells. Because both short-term effector and long-lived memory cells are thought to secrete IFN-γ immediately on antigen stimulation,35,36 this method allows identification of all T cells responding to a specific antigen. Thus, IFN-γ secretion in response to stimulation with virus-infected cells should provide an estimate of the total pool of functional viral-specific CD8 T cells. We used uniformly HIV-infected autologous CD4 T cells as stimulator cells to identify by flow cytometry IFN-γ–producing HIV-specific CD8+ T cells from the PBMC of 7 HIV-seropositive subjects. In 5 of 7 subjects (subjects 219, 307, 350, 606, 701), HIV-specific IFN-γ–secreting CD8 T cells were detectable, but in 2 subjects (subjects 216, 237) no IFN-γ–producing cells could be visualized above the background of 0.01%. IFN-γ–producing cells in the positive subjects varied from 0.3% to 2.9% of CD8 T cells. We have previously found that brief culture of cells ex vivo in the presence of IL-2 enhances viral-specific cytotoxicity in some subjects.20 37 Thus, we tested whether exogenous IL-2 also enhances IFN-γ production. In 3 subjects who were on HAART therapy and had undetectable plasma virus (350, 606, 701), the same frequency of IFN-γ–producing cells was observed in the presence or absence of exogenous IL-2. In 2 other subjects (subjects 219, 307) who had detectable plasma viremia, the addition of IL-2 resulted in a 4- to 5-fold increase in the number of IFN-γ–producing cells. For the 2 other subjects (subjects 216, 237) in whom HIV-specific IFN-γ–secreting CD8 T cells were not detected in the absence of IL-2, the addition of IL-2 resulted in a weak but detectable IFN-γ response in one. For all subjects taken together, there was a 1.7-fold higher level of IFN-γ–producing cells in the presence of IL-2 (median frequency, 0.4% of CD8 T cells without IL-2 vs 0.7% of CD8 T cells with IL-2). HIV-specific CD69 up-regulation on CD8 T cells was also more pronounced in the presence of IL-2 (median frequency, 0.1% of CD8 T cells without IL-2 vs 4.9% of CD8 T cells with IL-2). Figure 1 depicts the flow cytometric analysis of CD69 up-regulation and IFN-γ production in one representative subject. Cumulative data for all subjects tested are shown in Figure 2.

IFN-γ secretion and CD69 up-regulation in CD8 T cells from representative subject 307 in response to stimulation with HIV-infected CD4 T cells is enhanced in the presence of IL-2.

Immunomagnetically isolated CD8+ T cells were stimulated with uniformly HIV-infected CD4 T cells in the presence (D) or absence (B) of 600 IU/mL of IL-2. Cultures stimulated with uninfected CD4 blasts in the presence (C) or absence (A) of IL-2 served as controls. Cells were incubated overnight in the presence of Brefeldin A and then stained externally for CD8-Cy5 and CD69-PE and internally for IFN-γ FITC.

IFN-γ secretion and CD69 up-regulation in CD8 T cells from representative subject 307 in response to stimulation with HIV-infected CD4 T cells is enhanced in the presence of IL-2.

Immunomagnetically isolated CD8+ T cells were stimulated with uniformly HIV-infected CD4 T cells in the presence (D) or absence (B) of 600 IU/mL of IL-2. Cultures stimulated with uninfected CD4 blasts in the presence (C) or absence (A) of IL-2 served as controls. Cells were incubated overnight in the presence of Brefeldin A and then stained externally for CD8-Cy5 and CD69-PE and internally for IFN-γ FITC.

IFN-γ production and CD69 up-regulation in HIV-specific CD8 T cells is IL-2 dependent in some seropositive subjects.

CD8 T cells from seropositive subjects were stimulated with uniformly HIV-infected CD4 T cells, as in Figure 1. CD8 T cells stimulated with infected CD4 T-cell blasts in the presence (▧) or absence (░) of IL-2 were stained for IFN-γ (A) and CD69 (B). Data shown are the results after subtracting the values obtained with uninfected CD4 blasts under the same culture conditions.

IFN-γ production and CD69 up-regulation in HIV-specific CD8 T cells is IL-2 dependent in some seropositive subjects.

CD8 T cells from seropositive subjects were stimulated with uniformly HIV-infected CD4 T cells, as in Figure 1. CD8 T cells stimulated with infected CD4 T-cell blasts in the presence (▧) or absence (░) of IL-2 were stained for IFN-γ (A) and CD69 (B). Data shown are the results after subtracting the values obtained with uninfected CD4 blasts under the same culture conditions.

IFN-γ–producing cells either were not detectable or were present at very low levels in most subjects tested despite our use of uniformly HIV-infected targets for stimulation. Because nearly 30% to 80% of circulating CD8+ T cells from these subjects exhibited an effector-memory phenotype (RA or RO+, L-selectin−, DR+ cells; data not shown), we tested IFN-γ production after stimulation with PMA–ionomycin in 5 subjects. Under these conditions, 14% to 69% of CD8+cells produced IFN-γ (data not shown).

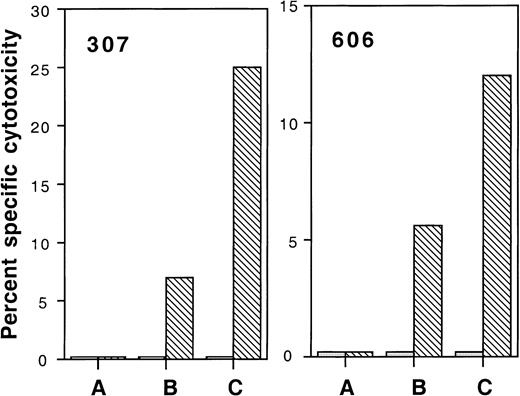

Lysis of primary HIV-infected CD4 T cells by freshly isolated and overnight cultured PBMC

We also assessed whether lytic function of HIV-specific CD8 T cells corresponded with their ability to secrete IFN-γ. Uniformly HIV-infected CD4 targets used as stimulator cells for IFN-γ production were also used as targets in 51Cr release assays. In 2 subjects tested (subjects 606, 307) with 2.9% and 0.4% IFN-γ–producing cells after exposure to HIV, no detectable cytotoxicity was seen when PBMC were used directly. However, overnight culture in medium alone restored a modicum of HIV-specific cytotoxicity (5%-7%) at an E:T ratio of 100:1, which was substantially enhanced to 12% to 25% by adding exogenous IL-2 (Figure3).

PBMC cultured overnight in IL-2 exhibit enhanced cytolytic ability against HIV-infected CD4 T-cell targets.

Autologous HIV-infected (▧) and uninfected (░) CD4 T-cell blasts were used as targets. Effector cells were thawed PBMC (A) or were cultured overnight in the absence (B) or presence (C) of IL-2 and were tested at an E:T ratio of 100:1.

PBMC cultured overnight in IL-2 exhibit enhanced cytolytic ability against HIV-infected CD4 T-cell targets.

Autologous HIV-infected (▧) and uninfected (░) CD4 T-cell blasts were used as targets. Effector cells were thawed PBMC (A) or were cultured overnight in the absence (B) or presence (C) of IL-2 and were tested at an E:T ratio of 100:1.

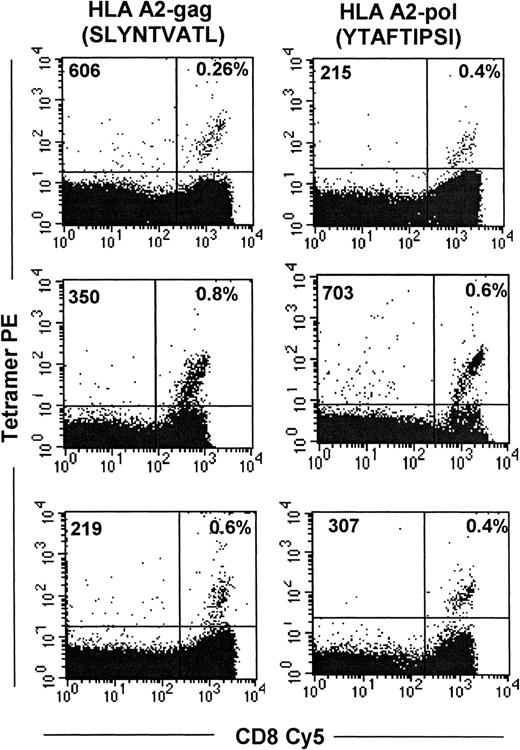

HIV-specific CD8 T cells can be identified by tetramer staining

Although our results using HIV-infected autologous stimulator or target cells suggest that HIV-specific CD8+ T cells may be functionally compromised in vivo, the assay does not identify all antigen-specific T cells, only those that are functionally active. Thus, we used MHC–peptide tetramers to enumerate and characterize HIV epitope-specific CD8 T cells. PBMC from a cohort of 15 HLA-A2–expressing subjects infected with HIV-1 were examined for the frequency of CTL-recognizing epitopes restricted by this allele. The clinical characteristics of the subjects, who were at various stages of the disease, are shown in Table 1. CD8 T cells directed against a well-characterized gag epitope SLYNTVATL38,39 and a novel RT epitope YTAFTIPSI that we recently described30 were directly visualized with HLA-A2 MHC–peptide tetramers. For samples that stained above background, the frequency of tetramer-binding cells ranged from 0.2% to 1.4% and 0.2% to 0.8% of the total CD8 T cells for the A2-restricted gag and pol epitopes, respectively. Nine of 15 (60%) subjects recognized the gag epitope, which is similar to data reported by Ogg et al.40 CD8 T cells directed against the novel RT epitope were identified in 5 of 14 (35%) subjects, which approximately corresponds to the frequency reported for recognition of the RT epitope IV9 (ILKEPVHGV).40 Binding of more than 0.1% to both tetramers was seen in 2 of 14 subjects, and in 2 others neither epitope was recognized. Figure 4shows representative flow cytometric data for each of the epitopes. No correlation was observed between viral load and tetramer positivity in these subjects. However, the study group consisted of a heterogeneous mix of subjects infected for variable time periods and treated with different antiretroviral regimens, which may have influenced the results (data not shown).

Identification of circulating HIV-specific CD8+ T cells with HLA-A2–SLYNTVATL and HLA-A2–YTAFTIPSI tetrameric complexes.

PBMC were costained with streptavidin PE–conjugated tetramers and CD8-Cy5. Flow cytometric analysis was performed on a lymphocyte-gated population. Results represent analyses of samples from representative seropositive subjects.

Identification of circulating HIV-specific CD8+ T cells with HLA-A2–SLYNTVATL and HLA-A2–YTAFTIPSI tetrameric complexes.

PBMC were costained with streptavidin PE–conjugated tetramers and CD8-Cy5. Flow cytometric analysis was performed on a lymphocyte-gated population. Results represent analyses of samples from representative seropositive subjects.

Phenotypic characteristics of tetramer-binding, HIV-specific CD8 T cells

Because HIV-1 disease progression is associated with phenotypic changes in peripheral blood CD8 T cells that may be reflective of functional changes within the HIV-specific CD8 T-cell compartment, the phenotypic characteristics of tetramer-binding cells were analyzed by 3-color flow cytometry. Antigen-primed T cells have been shown to segregate into 2 distinct phenotypic subsets: a memory population that expresses the RO isoform of CD45 and is CD27+ and an effector population that expresses the RA isoform of CD45 and is CD27−.41,42 As shown in Table2, applying these criteria, the tetramer-binding cells from most of the subjects in this study are of the memory subtype. The tetramer-positive cells were bcl-2 high, which is also suggestive of a memory subtype.43 However, the tetramer-positive cells were CD28− and CD62L−and expressed granzyme A, which are thought to be characteristics of activated effector cells.42 The acute activation marker CD38, which has been implicated as an adverse prognostic marker for disease progression, was not expressed on most tetramer-positive cells.44 45 The tetramer-positive cells were heterogeneous with respect to other activation markers such as CD57 and HLA-DR. Taken together, our data suggest that the tetramer-positive cells showed a mixed pattern of memory and effector characteristics.

Phenotypic analysis of tetramer-stained CD8 T cells from 9 HIV-seropositive subjects

| Patients . | CD27 . | CD28 . | CD38 . | CD57 . | CD62L . | HLA-DR . | CD45RO . | CD45RA . | CB9 . | Bcl-2 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 136* | +++ | ± | ± | + | − | ++++ | +++ | ± | ND | ND |

| 219* | ++++ | + | ± | ± | ± | + | +++ | ± | ++ | ++ |

| 350* | ++++ | + | − | + | + | +++ | +++ | + | + | +++ |

| 606* | ++++ | + | − | ++ | ± | ++++ | ++++ | + | ++++ | +++ |

| 701* | +++ | − | − | + | ± | ND | +++ | + | +++ | ++++ |

| 705* | ++++ | ND | +++ | + | + | ++ | + | ++ | + | ++ |

| 215† | ++++ | + | + | + | − | ++ | +++ | ± | ++++ | ND |

| 307† | ++++ | − | + | ++ | ± | ± | ++++ | − | ++++ | ++++ |

| 703† | ++++ | + | ++ | − | ± | +++ | ++ | ± | ND | ND |

| Average expression | ++++ | ± | + | + | ± | ++ | +++ | + | +++ | +++ |

| Patients . | CD27 . | CD28 . | CD38 . | CD57 . | CD62L . | HLA-DR . | CD45RO . | CD45RA . | CB9 . | Bcl-2 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 136* | +++ | ± | ± | + | − | ++++ | +++ | ± | ND | ND |

| 219* | ++++ | + | ± | ± | ± | + | +++ | ± | ++ | ++ |

| 350* | ++++ | + | − | + | + | +++ | +++ | + | + | +++ |

| 606* | ++++ | + | − | ++ | ± | ++++ | ++++ | + | ++++ | +++ |

| 701* | +++ | − | − | + | ± | ND | +++ | + | +++ | ++++ |

| 705* | ++++ | ND | +++ | + | + | ++ | + | ++ | + | ++ |

| 215† | ++++ | + | + | + | − | ++ | +++ | ± | ++++ | ND |

| 307† | ++++ | − | + | ++ | ± | ± | ++++ | − | ++++ | ++++ |

| 703† | ++++ | + | ++ | − | ± | +++ | ++ | ± | ND | ND |

| Average expression | ++++ | ± | + | + | ± | ++ | +++ | + | +++ | +++ |

Relative expression of markers for tetramer populations. Fraction of cells expressing a given marker: −, 0%-10%; ±, 10%-20%; +, 20%-40%; ++, 40%-60%; +++, 60%-80%; ++++, > 80%. ND, not determined.

PBMC stained with gag tetramer.

PBMC stained with RT tetramer.

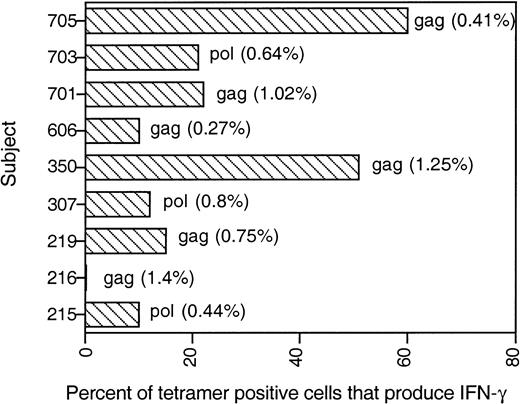

Only a fraction of circulating HIV-specific CD8 T cells produces IFN-γ in response to peptide-specific stimulation

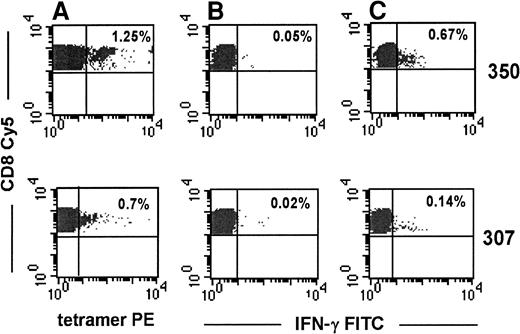

To investigate the functional status of tetramer-binding, HIV-specific CD8 T cells, we studied cytokine production by costaining for tetramer PE and intracellular IFN-γ–FITC 8 hours after PBMC were stimulated with the cognate peptide corresponding to each tetramer. Representative data from stage A1 subject 350 (CD4 count, 1005/μL) and stage B2 subject 307 (CD4 count, 280/μL) are shown in Figure 5. The IFN-γ–producing population was generally tetramer-negative after stimulation with the cognate peptide, presumably because of TcR down-modulation that accompanies activation. Only a fraction of tetramer-positive CD8 T cells produced IFN-γ after specific stimulation (Figure6). In 7 of 9 subjects, less than 25% of the tetramer-stained cells produced IFN-γ in response to peptide-specific stimulation. The 2 subjects (subjects 350, 705) with a high proportion of IFN-γ–producing tetramer-positive cells had no clinical symptoms and had well-maintained CD4 counts of 1005/μL and 650/μL. Five of 7 subjects with less than 25% IFN-γ–producing tetramer-positive cells had a history of HIV-related CDC stage B or C symptoms.

Representative flow cytometric analyses of peptide-specific IFN-γ production by tetramer-binding cells.

PBMC from subjects 307 and 350 were stimulated with the relevant HLA-A2 gag or RT peptide for 8 hours. Brefeldin A (10 μmol/L) was added during the last 4 hours of incubation. Cells were washed and stained with tetramer PE, CD8-Cy5, and IFN-γ FITC. (A) Percentages represent the proportion of tetramer-staining cells within the CD8-gated population. (B, C) IFN-γ–secreting CD8 T cells in the absence or presence, respectively, of cognate peptide.

Representative flow cytometric analyses of peptide-specific IFN-γ production by tetramer-binding cells.

PBMC from subjects 307 and 350 were stimulated with the relevant HLA-A2 gag or RT peptide for 8 hours. Brefeldin A (10 μmol/L) was added during the last 4 hours of incubation. Cells were washed and stained with tetramer PE, CD8-Cy5, and IFN-γ FITC. (A) Percentages represent the proportion of tetramer-staining cells within the CD8-gated population. (B, C) IFN-γ–secreting CD8 T cells in the absence or presence, respectively, of cognate peptide.

Only a fraction of tetramer-binding cells secretes IFN-γ in response to the tetrameric peptide.

IFN-γ production, assayed as described in Figure 5, is shown for all subjects tested. Numbers adjacent to each bar represent the percentage of tetramer-positive CD8 T cells for each subject.

Only a fraction of tetramer-binding cells secretes IFN-γ in response to the tetrameric peptide.

IFN-γ production, assayed as described in Figure 5, is shown for all subjects tested. Numbers adjacent to each bar represent the percentage of tetramer-positive CD8 T cells for each subject.

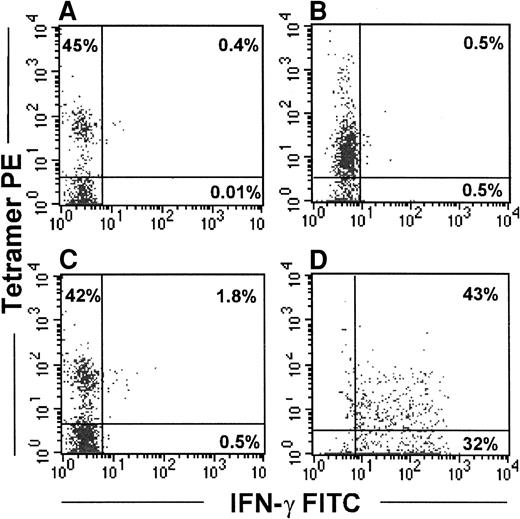

Because the direct measurement of functional activity in uncultured PBMC can be relatively insensitive, in 2 subjects (subjects 219, 606) we also immunomagnetically selected the tetramer-binding cells using anti-PE Miltenyi beads for functional studies. A significant enrichment in tetramer-positive cells was observed after selection (61% and 42% of CD8 T cells from a starting population of 0.7% and 0.27% of CD8 T cells, respectively; data not shown). Because tetramer binding itself may not be a sufficient stimulus for IFN-γ secretion, the selected cells were incubated with the relevant gag SLYNTVATL peptide-pulsed APC immediately after selection. Even under these conditions, few IFN-γ–producing cells could be discerned (Figure7C). However, after a few days of culture in the presence of IL-2 (600 IU/mL) and IL-15 (25 ng/mL), the selected cells showed a significant level of peptide-specific IFN-γ production (Figure 7D). However, because tetramer binding can block TcR sites, we cannot rule out the possibility that tetramer selection might have interfered with IFN-γ production when immunomagnetically enriched cells were tested immediately after selection.

Immunomagnetically selected tetramer-positive cells secrete IFN-γ in response to peptide only after in vitro culture.

Tetramer-stained cells from subject 606 were isolated from PBMC using α-PE Miltenyi beads and cultured for 5 days in the presence of IL-2 and IL-15. Fresh or cultured cells were stimulated with autologous BLCL alone (A, B) or with autologous BLCL pulsed with the relevant peptide (C, D) for 8 hours. Brefeldin A (10 μmol/L) was added during the last 4 hours of incubation. Cells were washed and stained with gag tetramer PE, CD8-Cy5, and IFN-γ FITC. Left panels depict tetramer-positive cells tested immediately after immunomagnetic selection. Right panels show IFN-γ–secreting cells after culture. Analyses are performed on the CD8-gated population.

Immunomagnetically selected tetramer-positive cells secrete IFN-γ in response to peptide only after in vitro culture.

Tetramer-stained cells from subject 606 were isolated from PBMC using α-PE Miltenyi beads and cultured for 5 days in the presence of IL-2 and IL-15. Fresh or cultured cells were stimulated with autologous BLCL alone (A, B) or with autologous BLCL pulsed with the relevant peptide (C, D) for 8 hours. Brefeldin A (10 μmol/L) was added during the last 4 hours of incubation. Cells were washed and stained with gag tetramer PE, CD8-Cy5, and IFN-γ FITC. Left panels depict tetramer-positive cells tested immediately after immunomagnetic selection. Right panels show IFN-γ–secreting cells after culture. Analyses are performed on the CD8-gated population.

Circulating HIV-specific CD8 T cells are not cytolytic against peptide-pulsed targets

To determine the cytolytic ability of in vivo–generated tetramer- staining cells, uncultured PBMC from 8 subjects with detectable tetramer-binding cells (subjects 215, 216, 219, 237, 307, 350, 606, 705) were tested against the relevant gag or RT peptide–pulsed autologous BLCL lines or A2-expressing T2 cells. In all subjects, peptide-specific cytotoxicity at an E:T ratio of 100:1 was well below the 5% background cutoff level with fresh or thawed PBMC (highest level was 1.4%). Overnight incubation of the cells in IL-2 did not result in a substantial increase in peptide-specific lysis in any of the subjects (data not shown).

Discussion

The persistence of HIV viral replication, despite a strong viral-specific CD8 T-cell response, suggests a functional deficiency of these cells in vivo. Most functional studies have used ex vivo expanded CD8 T cells cultured in the presence of cytokines.46However, it is unclear whether the results obtained in these in vitro systems are representative of the in vivo picture. Our goal in this study was to determine the functional properties of HIV-specific CD8 T cells directly ex vivo before in vitro culture could modify their characteristics. To evaluate the functional status of circulating HIV-specific CD8 T cells, we used MHC–peptide tetramer staining and a novel flow cytometric assay to measure IFN-γ secretion response to primary HIV-infected cells. Our results suggest that a significant proportion of HIV-specific CD8 T cells are functionally compromised in chronically infected subjects.

Multiparametric flow cytometric assays that detect rapid intracellular accumulation of cytokines after a brief period of in vitro stimulation are increasingly used to measure in vivo T-cell frequencies for specific antigens. Kern et al47 have used this assay to measure peptide-specific CD8 T-cell frequencies in samples from known HLA types in cytomegalovirus infection. However, studies from our laboratory and from others38,48,49 suggest that the immunodominant HIV epitopes recognized by seropositive subjects are not predictable on the basis of HLA haplotypes. Because most of the conserved HIV epitopes are represented on HIVIIIB-infected CD4 T-cell targets, IFN-γ secretion in response to these targets provides an efficient and unbiased method to enumerate the total pool of functional HIV-specific CD8 T cells in circulation. Moreover, an assay that does not rely on specific epitopes, as the tetramer technology does, may be more useful for an assessment of CD8 T-cell function during the course of the disease. This is because T cells recognizing specific epitopes with varying affinities may have differential requirements for CD4 help, which might differentially alter the CTL response to specific epitopes in chronic HIV infection.18 50

The frequencies of IFN-γ–producing CD8 T cells responding to HIV-infected CD4 T cells in our study are comparable to those reported for EBV-specific CD8 T cells in long-term healthy EBV carriers, using a similar flow cytometric IFN-γ–staining assay after stimulation with autologous BLCL.27 This is surprising considering that the level of antigenemia in HIV infection is likely to be much higher. The discrepancy between the global increase in the numbers of effector-memory CD8+ T cells, which can be induced to produce IFN-γ by stimulation with PMA and ionomycin, in many of these subjects, and the relatively small numbers of HIV-specific CD8 T cells detected by the assay also point to a possible accumulation of nonfunctional cells. Our ability to induce IFN-γ production in response to HIV-infected primary T cells in 1 of 2 nonresponders and to enhance IFN-γ production in 2 low responders by exposure to IL-2 also suggests CD8 T-cell dysfunction in these subjects. Moreover, we were able to restore HIV-specific lytic ability toward HIV-vaccinia–infected targets in some subjects in an earlier study37 and toward HIV-infected primary CD4 T-cell targets in this study by overnight exposure of PBMC to IL-2, also pointing to a lack of effector function in CD8 in vivo. We have found that in subjects with more advanced disease, HIV-specific cytolytic function cannot be rescued with IL-2, suggesting that CD8 T-cell dysfunction increases with disease progression, ultimately approaching the profound anergy recently reported in patients with metastatic melanoma.37 51

To address directly the issue of the existence of HIV-specific CD8 T cells without effector function, we also performed functional and phenotypic characterization on tetramer-staining, HIV-specific CD8 T cells because this method identifies all CD8 T cells directed toward a specific epitope irrespective of their functional status. As suggested by Spiegel et al,52 the nonfunctional fraction of tetramer-stained cells can be used as an index of the accumulation of virus-specific CD8 T cells without effector function in HIV disease. HLA-A2 tetramers were used to visualize HIV epitope-specific CD8 T cells directed against an HIV-gag epitope, SLYNTVATL, and a novel HIV-RT epitope, YTAFTIPSI.29,30,39 With tetramer staining we found that approximately 65% of HIV-infected subjects had CD8 T cells that recognized the gag epitope SLYNTVATL, which is in agreement with published data.40 CD8 T cells that recognize the novel A2-restricted RT epitope YTAFTIPSI, which we recently found to be well presented on HIV-infected primary CD4 T-cell targets,29 were present in approximately 35% of the subjects, a level similar to the well-studied IV9 RT epitope.40

In most subjects less than 25% of the tetramer-stained cells produced IFN-γ in response to peptide-specific stimulation. IFN-γ production is thought to have similar rapid secretion kinetics in both memory and effector cells.35,53 Thus, the lack of IFN-γ production by most tetramer-binding cells points to a functional defect in these cells. Our data are in contrast to studies of acute and memory responses in mouse and humans in which every tetramer-staining cell could be induced to secrete IFN-γ after antigen-specific stimulation.26,40 54 However, our ability to rescue peptide-specific IFN-γ secretion in immunomagnetically selected tetramer-positive cells by culturing them in the presence of IL-2 and IL-15 suggests that the cells are not terminally anergic.

The tetramer-staining cells from most subjects in this study were CD45RA−, CD45RO+, CD27+, and expressed bcl-2, suggestive of a long-lived memory subtype.41-43 A bias toward a memory-like phenotype in CD8 T cells, directed toward this A2-restricted gag epitope and a different A2-restricted RT epitope, has also been reported by other laboratories.23,55 However, the tetramer-stained cells expressed granzyme A and were CD28− and CD62L−, which are characteristics of effector cells.42,56 A recent study points to a more complex functional and phenotypic heterogeneity within the antigen-primed CD8 T-cell pool.57 Based on expression of the lymph node (LN)-homing chemokine receptor CCR7, CD45RA, and CD62L, CD8 T cells can be subdivided into a CD45RA−CCR7+ long-term memory subset, which is mostly positive for CD62L and homes to LN, and 2 subsets of tissue-homing CCR7−CD62L−effector CD8 T cells, which have been classified in that study as CD45RA− effector memory cells and CD45RA+terminal effector cells. How these patterns of phenotypic marker expression reflect in vivo function is unclear. The noteworthy absence of CD45RA+CD27− terminally differentiated CTLs within the tetramer-stained population, despite the presence of detectable viremia, may imply a defect in the generation of effector cells due to a dysfunctional milieu in chronic HIV infection. Other aberrant phenotypic characteristics, which may be the result of an altered cytokine milieu, have also been reported in HIV infection. Notable among them is the lack of perforin expression on lymph node, but not peripheral blood, CD8 T cells despite the presence of other granule components such as granzymes.58

Recent studies18,50 have suggested that the mere existence of antigen-primed CD8 T cells in vivo does not imply their functionality. Earlier studies20,37 from our laboratory have shown that freshly isolated CD8 T cells from HIV-infected subjects have down-modulated CD3ζ, the key signaling molecule of the TcR, and have reduced cytotoxicity in 51Cr release assays. After a brief period of culture in IL-2, they up-regulate CD3ζ and regain their lytic ability. Recently, Lee et al51 identified tumor-specific cells that were functionally unresponsive despite a sizable clonal expansion. In chronic LCMV infection of mice under conditions of CD4 deficiency, CD8 T cells can persist indefinitely in a functionally silenced state, underscoring the essential role of CD4 helper T cells in maintaining CD8 function.18 CD4 helper cells sustain CD8 function not only by providing IL-2 but also by providing essential costimulatory signals through CD40-CD40L interactions between activated CD4 T cells and dendritic cells.59-61 We found that fresh PBMC from all the subjects tested (8 of 8) were not cytolytic against SLYNTVATL (gag) and YTAFTIPSI (pol) peptide-pulsed targets. However, peptide-specific lines generated from the subjects by in vitro stimulation were highly cytolytic (data not shown). Our results are in agreement with those of Gray et al,55 who reported a similar lack of HIV-specific cytolysis by freshly isolated PBMC from seropositive subjects. Our data are in contrast to data reported by Ogg et al,40 who found a significant positive correlation between fresh cytolysis and tetramer staining. The discrepancy may be attributed to differences in the study populations. In fact we observed a relation between the functional defect with disease stage and CD4 count, but not with the viral load. Confounding factors may be antiviral drug therapy and duration of the infection.

In conclusion, by using a dual approach of MHC–peptide tetramer staining and IFN-γ secretion in response to primary HIV-infected cells, we found that a significant proportion of antiviral CD8 T cells may be functionally unresponsive in HIV infection. Our results also suggest that functional impairment of HIV-specific CD8 T cells may worsen with disease progression. With a better understanding of why virus-specific CD8 T-cell functions are compromised during persistent infection, it may become possible to devise ways to restore functional competence to preexisting virus-specific CD8 T cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Davis and D. Wiley for the HLA-A2 and β2 microglobulin plasmids and Zhan Xu for synthesis of the MHC–peptide tetramers.

Supported by grants R01 AI42519 (J.L.), R01 AI45406 (J.L.), R29 AI38819 (P.S.), and R21 AI45306 (P.S.) from the National Institutes of Health.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Premlata Shankar, Center for Blood Research, 800 Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: shankar@cbr.med.harvard.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal