Abstract

A prospective, multicenter, randomized trial was undertaken to compare the efficacy and toxicity of adriamycin with mitoxantrone within a 6-drug combination chemotherapy regimen for elderly patients (older than 60 years) with high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma (HGL) given for a minimum of 8 weeks. A total of 516 previously untreated patients aged older than 60 years were randomized to receive 1 of 2 anthracycline-containing regimens: adriamycin, 35 mg/m2intravenously (IV) on day 1 (n = 259), or mitoxantrone, 7 mg/m2 IV on day 1 (n = 257); with prednisolone, 50 mg orally on days 1 to 14; cyclophosphamide, 300 mg/m2 IV on day 1; etoposide, 150 mg/m2 IV on day 1; vincristine, 1.4 mg/m2 IV on day 8; and bleomycin, 10 mg/m2 IV on day 8. Each 2-week cycle was administered for a minimum of 8 weeks in the absence of progression. Forty-three patients were ineligible for analysis. The overall and complete remission rates were 78% and 60% for patients receiving PMitCEBO and 69% and 52% for patients receiving PAdriaCEBO (P = .05, P = .12, respectively). Overall survival was significantly better with PMitCEBO than PAdriaCEBO (P = .0067). However, relapse-free survival was not significantly different (P = .16). At 4 years, 28% of PAdriaCEBO patients and 50% of PMitCEBO patients were alive (P = .0001). Ann Arbor stage III/IV, World Health Organization performance status 2-4, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase negatively influenced overall survival from diagnosis. In conclusion, the PMitCEBO 8-week combination chemotherapy regimen offers high response rates, durable remissions, and acceptable toxicity in elderly patients with HGL.

Introduction

The incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) increases exponentially with age, and most patients are 60 years of age or older at diagnosis.1-3 A dramatic increase in the incidence of NHL is occurring that is not fully explained by advances in diagnosis, changes in pathological classification systems, and the impact of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. The rate of increase in adults in the United Kingdom, Europe, and the United States is approximately 3% to 4% per year, with mortality rates from NHL increasing at approximately 2% per year.3-6 The largest increase in incidence has occurred in the elderly,3 and a recent review has estimated that at least a doubling in the number of new lymphoma patients over 65 years of age will occur over the next 20 to 25 years concomitant with improvements in supportive care and the aging of Western populations.7

High-grade and aggressive histologies constitute most NHL diagnosed in the elderly. However, there is no consistent evidence for a difference in the distribution of main histologic subgroups between patients aged less than or more than 60.7 In the past, age limits for inclusion in clinical trials conducted in patients with NHL have meant that few randomized trials have specifically addressed the questions of therapeutic efficacy and toxicity in the elderly population,8 despite evidence that the prognostic impact of age occurs in conjunction with other factors.9-13Several hypotheses have been generated and examined to explain these results, including lymphoma biology itself, reduction in delivery of total dose and/or dose intensity, reduced treatment toxicity tolerance, and concomitant medical issues.14-16

During the 1980s, second- and third-generation combination chemotherapy regimens adapted for the elderly suggested similar outcomes with reduced toxicity in comparison to regimens for younger patients with similar histologies.17-25 In the prednisolone, adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, bleomycin, oncovin (vincristine), methotrexate (PACEBOM) alternating, weekly, combination chemotherapy regimen, the major toxicity problem was mucositis, which could be markedly reduced by the omission of methotrexate.26 In this modified regimen, PAdriaCEBO, the greatest contributor to toxicity is adriamycin. The addition of an anthracycline significantly increases the complete remission (CR) rate, the median time to treatment failure, and the 5-year overall survival rate in elderly patients with aggressive NHL.17 The possibly reduced toxicity, and excellent activity of mitoxantrone in aggressive NHL led to the establishment of several randomized trials comparing adriamycin with mitoxantrone in multiagent regimens.24 27-30 This study was undertaken to establish the response rates, overall survival, and disease-specific survival obtained with an 8-week, 6-drug regimen and to compare the efficacy and toxicity of PAdriaCEBO with PMitCEBO in elderly patients with high-grade NHL.

Patients, materials, and methods

Between January 1993 and February 1997, the British National Lymphoma Investigation (BNLI) conducted a randomized, multicenter trial in elderly patients with HGL comparing the multiagent PAdriaCEBO chemotherapy regimen with the PMitCEBO regimen. Eligibility criteria included age between 60 and 85 years; previously untreated high-grade lymphoma defined as large cell lymphoma and diffuse large-cell lymphoma, including immunoblastic lymphoma and diffuse mixed-cell lymphoma and excluding lymphoblastic and Burkitt lymphoma (intermediate- and/or high-grade malignancy, groups D through H according to the Working Formulation31); stage IB-IV disease; and normal renal, hepatic, and cardiac function. Patients with prior low-grade lymphoma, severe intercurrent illness, positive human immunodeficiency virus serology, or previous malignancy were excluded. A central BNLI panel reviewed all histology, and all staging was performed according to the Ann Arbor classification. Diagnostic and staging procedures at entry included, as a minimum, a full blood count; liver function tests; measurement of erythrocyte sedimentation rate, serum electrolytes, and calcium, phosphate, and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels; chest x-ray, computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis, bone marrow aspiration, and trephine. Examination of the cerebrospinal fluid was not performed unless clinically indicated. Randomization was performed centrally through the BNLI office for patients to receive either PAdriaCEBO or PMitCEBO. Ethics committee approval was obtained in all participating centers.

Treatment regimens

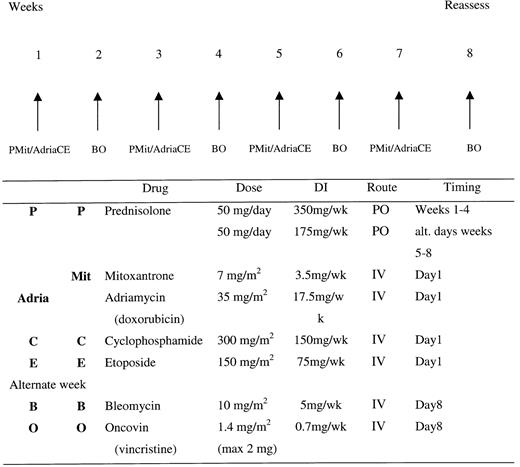

The 2 drug regimens were delivered as outlined in Figure1. The PAdriaCEBO regimen was administered as follows: prednisolone, 50 mg orally given weeks 1 to 4 and then on alternate days at week 5 onward; adriamycin, 35 mg/m2 given intravenously on day 1; cyclophosphamide, 300 mg/m2 given intravenously on day 1; etoposide, 150 mg/m2 given intravenously on day 1; vincristine, 1.4 mg/m2 (to a maximum of 2 mg) given intravenously on day 8; and bleomycin, 10 mg/m2 given intravenously on day 8, for a minimum of 8 weeks, in the absence of progression. The PMitCEBO regimen was administered in an identical fashion, with the exception that adriamycin was replaced with mitoxantrone, 7 mg/m2 given intravenously on day 1. Allopurinol was administered for the first 4 weeks of therapy, and cotrimoxazole, 480 mg orally twice a day, was administered on alternate days throughout and until 2 weeks after completion of therapy. Otherwise, prophylactic antibiotics were not administered. Dose modifications were as follows: If the absolute neutrophil count was below 0.5 × 109/L, the next cycle was delayed 1 week; if the absolute neutrophil count was between 0.5 × 109/L and 1.0 × 109/L, 65% of the total dose of cyclophosphamide, adriamycin/mitoxantrone, and etoposide was administered. There were no reductions in the dose and timing of vincristine or bleomycin, nor were modifications made for thrombocytopenia. Platelet support was recommended if there were clinical signs of bleeding and if the platelet count was below 40 × 109/L, and prophylactic platelet support was recommended if the platelet count was below 10 × 109/L. No dosage adjustments were made for anemia, and blood transfusions were administered to maintain a hemoglobin level above 10 g/dL. Dose modification for hepatic impairment was recommended as follows: bilirubin 35 to 50 μmol/L, 50% of adriamycin/mitoxantrone dose; bilirubin above 50 μmol/L, 25% of adriamycin/mitoxantrone dose. Bleomycin was discontinued if any signs of pulmonary infiltration or fibrosis were seen to develop. No radiotherapy or prophylactic treatment of central nervous system disease was given. Growth factors were not routinely used. Patients with central nervous system disease at presentation were treated with alternate methotrexate, 12 mg intrathecally, and cytarabine arabinoside, 50 mg intrathecally, twice a week for 3 weeks and then weekly to a total of 12 doses.

Treatment regimens for PAdriaCEBO and PMitCEBO.

Treatment regimens were administered for 4 cycles at 2-week intervals. DI, dose intensity; PO, per oral; IV, intravenous.

Treatment regimens for PAdriaCEBO and PMitCEBO.

Treatment regimens were administered for 4 cycles at 2-week intervals. DI, dose intensity; PO, per oral; IV, intravenous.

Response

Reevaluation was performed 8 weeks after commencement of chemotherapy. CR was defined as complete disappearance of all disease manifestations and the reversal of all previously abnormal investigations for at least 4 weeks. Progressive partial response (PPR) was defined as the disappearance of at least 50% of known disease with continued resolution on therapy. Nonprogressive partial response (NPPR) was defined as the disappearance of at least 50% of known disease without continued resolution during continued therapy or disease reexpansion (but still less than 50% of disease at presentation). No response (NR) was defined as less than 50% response. Minimal residual masses were judged to represent PPR, and further therapy was withheld. If no progression had occurred for 1 year, the response was changed to CR retrospectively.

Statistical analysis

The trial was planned to accrue 500 patients. Assuming a 10% ineligibility rate, this gave a 90% chance of detecting an overall improvement in survival rate of 15% at the 5% significance level assuming the 2-year survival in the PAdriaCEBO arm was 40%.26,32 Complete remission rates were compared by the use of the χ2 test, with Yates' correction as appropriate.33 Kaplan-Meier survival curves were calculated by the life table method and statistical comparison of curves performed by the log-rank test.34 Overall survival was defined as the time from randomization to death from any cause, and patients still alive were censored at the date that they were last seen alive. Cause-specific survival was analyzed from date of randomization to date of death from NHL, and patients who had nontreatment-related deaths in the presence of NHL were censored at that time. Progression-free survival was defined as time to disease progression or death from any cause. Prognostic factors were analyzed by a means of proportional hazards model.35

Results

The demographic characteristics of the 473 eligible patients enrolled in this study are presented in Table1. Both treatment groups were well balanced regarding baseline characteristics. There were no statistical differences in the age-adjusted prognostic factors. Forty-three patients (8%) were found to be incorrectly enrolled, 6% (16 of 259) were ineligible in the PAdriaCEBO arm and 11% (27 of 257) in the PMitCEBO arm (P = ns). After central pathology review, 40 patients had their histologic diagnosis changed from HGL and 3 patients were ineligible for other reasons: 1 because the patient was too young and the other 2 because they were too old. In addition, a further 7 eligible patients were lost to follow-up for the survival analyses.

Patient characteristics

| . | PAdriaCEBO (%) . | PMitCEBO (%) . | χ2 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of eligible patients | 243 | 230 | ||

| Male, no. (%) | 117 (48) | 118 (51) | 0.35 | .55 |

| Years of age, median (range) | 71 (60-84) | 71 (60-85) | .68* | |

| WHO PS, median (range) | 1 (0-4) | 1 (0-4) | .42 | |

| WHO PS, no. (%) | ||||

| 0 | 45 (20) | 59 (27) | ||

| 1 | 104 (46) | 86 (39) | ||

| 2 | 55 (24) | 45 (21) | ||

| 3 | 20 (9) | 23 (11) | ||

| 4 | 3 (1) | 5 (2) | ||

| “B” symptoms, no. (%) | 122 (54) | 105 (48) | 1.75 | .19 |

| Ann Arbor stage, no. (%) | ||||

| I | 15 (6) | 16 (7) | 0.48 | .49† |

| II | 80 (34) | 68 (30) | ||

| III | 49 (21) | 52 (23) | ||

| IV | 92 (39) | 93 (41) | ||

| Unknown, no. (%) | 7 (2) | 1 (< 1) | ||

| No. of extranodal sites, median (range) | 0 (0-3) | 0 (0-4) | .23* | |

| Extranodal sites, no. (%) | ||||

| 0 | 133 (55) | 115 (50) | ||

| 1 | 89 (37) | 85 (37) | ||

| 2 | 18 (7) | 26 (11) | ||

| 3 | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | ||

| 4 | 0 (0) | 1 (< 1) | ||

| Marrow involvement, no. | .33 | |||

| Negative | 186 | 182 | ||

| Positive | 41 | 30 | ||

| Unknown | 16 | 18 | ||

| LDH, median (range) | 548 (40-5382) | 466 (30-7759) | .14 | |

| Not performed, no. (%) | 75 (31) | 65 (28) | ||

| Age-adjusted IPI, no. (%) | ||||

| 0 | 45 (19) | 41 (18) | ||

| I | 93 (39) | 88 (38) | 0.27 | .97 |

| II | 72 (30) | 71 (31) | ||

| III | 27 (11) | 29 (13) |

| . | PAdriaCEBO (%) . | PMitCEBO (%) . | χ2 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of eligible patients | 243 | 230 | ||

| Male, no. (%) | 117 (48) | 118 (51) | 0.35 | .55 |

| Years of age, median (range) | 71 (60-84) | 71 (60-85) | .68* | |

| WHO PS, median (range) | 1 (0-4) | 1 (0-4) | .42 | |

| WHO PS, no. (%) | ||||

| 0 | 45 (20) | 59 (27) | ||

| 1 | 104 (46) | 86 (39) | ||

| 2 | 55 (24) | 45 (21) | ||

| 3 | 20 (9) | 23 (11) | ||

| 4 | 3 (1) | 5 (2) | ||

| “B” symptoms, no. (%) | 122 (54) | 105 (48) | 1.75 | .19 |

| Ann Arbor stage, no. (%) | ||||

| I | 15 (6) | 16 (7) | 0.48 | .49† |

| II | 80 (34) | 68 (30) | ||

| III | 49 (21) | 52 (23) | ||

| IV | 92 (39) | 93 (41) | ||

| Unknown, no. (%) | 7 (2) | 1 (< 1) | ||

| No. of extranodal sites, median (range) | 0 (0-3) | 0 (0-4) | .23* | |

| Extranodal sites, no. (%) | ||||

| 0 | 133 (55) | 115 (50) | ||

| 1 | 89 (37) | 85 (37) | ||

| 2 | 18 (7) | 26 (11) | ||

| 3 | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | ||

| 4 | 0 (0) | 1 (< 1) | ||

| Marrow involvement, no. | .33 | |||

| Negative | 186 | 182 | ||

| Positive | 41 | 30 | ||

| Unknown | 16 | 18 | ||

| LDH, median (range) | 548 (40-5382) | 466 (30-7759) | .14 | |

| Not performed, no. (%) | 75 (31) | 65 (28) | ||

| Age-adjusted IPI, no. (%) | ||||

| 0 | 45 (19) | 41 (18) | ||

| I | 93 (39) | 88 (38) | 0.27 | .97 |

| II | 72 (30) | 71 (31) | ||

| III | 27 (11) | 29 (13) |

χ2 with 1 degree of freedom.

WHO indicates World Health Organization; PS, performance status; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; IPI, international prognostic index.

Mann-Whitney U test.

I/II versus III/IV.

Response

Response rates for assessable patients in both treatment arms are outlined in Table 2. For patients receiving PMitCEBO the CR rate was 60% (138 of 230), and 52% (126 of 243) patients receiving PAdriaCEBO had a CR to therapy (P = .12). Partial response rates were not significantly different; however, overall response rates were significantly in favor of treatment with PMitCEBO, 78% versus 69% (χ2 = 4.53, P = .05). Three patients are not evaluable for response; 1 patient refused treatment, and 2 patients were lost to follow-up.

Response to treatment

| . | PAdriaCEBO, no. (%) . | PMitCEBO, no. (%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CR | 125 (52) | 137 (60) | .12 |

| ICRD | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | |

| PPR | 18 (8) | 16 (7) | |

| NPPR | 24 (10) | 26 (11) | |

| ORR | 168 (69) | 180 (78) | .05 |

| NR | 72 (30) | 50 (22) | |

| NE* | 3 | ||

| Total | 243 | 230 |

| . | PAdriaCEBO, no. (%) . | PMitCEBO, no. (%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CR | 125 (52) | 137 (60) | .12 |

| ICRD | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | |

| PPR | 18 (8) | 16 (7) | |

| NPPR | 24 (10) | 26 (11) | |

| ORR | 168 (69) | 180 (78) | .05 |

| NR | 72 (30) | 50 (22) | |

| NE* | 3 | ||

| Total | 243 | 230 |

ICRD indicates in complete remission death; PPR, progressive partial response; NPPR, nonprogressive partial response; ORR, overall response rate; NR, no response; NE, not evaluable.

One patient refused treatment; 2 patients were lost to follow-up.

Survival

The median follow-up time is 20 months for all patients and 26 months for complete responders. Survival curves are illustrated in Figures 2 to4, demonstrating overall, relapse-free, and lymphoma-specific survival. There was a significant overall survival advantage for patients receiving PMitCEBO (P = .0067), with a trend for improved cause-specific survival (P = .06). The 4-year cause-specific survival was 35% for patients receiving PAdriaCEBO and 59% for patients receiving PMitCEBO (P < .001), and the 4-year overall survival was significantly inferior for patients receiving PAdriaCEBO (28%) compared with those receiving PMitCEBO (50%) (P < .001). Relapse-free survival was not significantly different between the 2 arms of the trial (P = .16). Overall and cause-specific survival were negatively influenced by treatment, age, stage at presentation, and performance status. LDH was not routinely performed by some centers and was not included in these analyses; however, LDH significantly influenced overall and progression-free survival (P = .03 and P = .04, respectively). After multivariate analysis, these factors continued to carry prognostic value (Table3).

Univariate and multivariate analysis of prognostic factors for survival

| Factor . | Relative risk . | χ2value . | P value . | 95% confidence interval . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | ||||

| Treatment | 1.46 | 7.97 | .005 | 1.12-1.91 |

| PAdriaCEBO vs PMitCEBO | ||||

| Age, ≤ 70 vs > 70 | 1.40 | 6.19 | .01 | 1.07-1.83 |

| Stage, I/II vs III/IV | 2.18 | 29.08 | < .001 | 1.62-2.93 |

| Sex, male vs female | 1.16 | 1.18 | .28 | 0.89-1.51 |

| WHO PS, 0/1 vs 2-4 | 2.04 | 26.32 | < .0001 | 1.57-2.67 |

| Extranodal sites, 0/1 vs > 1 | 1.14 | 0.39 | .53 | 0.75-1.73 |

| Multivariate | ||||

| Treatment | 1.58 | 10.87 | .001 | 1.21-2.06 |

| PMitCEBO vs PAdriaCEBO | ||||

| Age, ≤ 70 vs > 70 | 1.45 | 7.15 | .008 | 1.11-1.89 |

| Stage, I/II vs III/IV | 2.05 | 23.60 | < .0001 | 1.51-2.76 |

| Sex, male vs female | 1.19 | 1.72 | .19 | 0.92-1.55 |

| WHO PS, 0/1 vs 2-4 | 1.85 | 18.64 | < .0001 | 1.41-2.42 |

| Extranodal sites, 0/1 vs > 1 | 1.23 | 0.90 | .34 | 0.80-1.88 |

| Factor . | Relative risk . | χ2value . | P value . | 95% confidence interval . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | ||||

| Treatment | 1.46 | 7.97 | .005 | 1.12-1.91 |

| PAdriaCEBO vs PMitCEBO | ||||

| Age, ≤ 70 vs > 70 | 1.40 | 6.19 | .01 | 1.07-1.83 |

| Stage, I/II vs III/IV | 2.18 | 29.08 | < .001 | 1.62-2.93 |

| Sex, male vs female | 1.16 | 1.18 | .28 | 0.89-1.51 |

| WHO PS, 0/1 vs 2-4 | 2.04 | 26.32 | < .0001 | 1.57-2.67 |

| Extranodal sites, 0/1 vs > 1 | 1.14 | 0.39 | .53 | 0.75-1.73 |

| Multivariate | ||||

| Treatment | 1.58 | 10.87 | .001 | 1.21-2.06 |

| PMitCEBO vs PAdriaCEBO | ||||

| Age, ≤ 70 vs > 70 | 1.45 | 7.15 | .008 | 1.11-1.89 |

| Stage, I/II vs III/IV | 2.05 | 23.60 | < .0001 | 1.51-2.76 |

| Sex, male vs female | 1.19 | 1.72 | .19 | 0.92-1.55 |

| WHO PS, 0/1 vs 2-4 | 1.85 | 18.64 | < .0001 | 1.41-2.42 |

| Extranodal sites, 0/1 vs > 1 | 1.23 | 0.90 | .34 | 0.80-1.88 |

For abbreviations, see Table 1.

Deaths

There were significantly fewer deaths in the mitoxantrone-containing arm (107 of 230 vs 137 of 243; χ2 = 4.21, P = .04), with 100 deaths occurring from NHL for patients receiving PAdriaCEBO and 84 deaths for patients receiving PMitCEBO (P = .45). The causes of death in both treatment groups are listed in Table4. There was a trend for an increase in risk of treatment-related deaths in the PAdriaCEBO arm (22 of 243 vs 11/230, respectively; χ2 = 2.70, P = .10). There were no differences in cardiac deaths, with 8 in each arm.

Causes of death

| Cause of death . | PAdriaCEBO, no. (%) . | PMitCEBO, no. (%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHL | 100 (72) | 84 (79) | .30 |

| Treatment-related with NHL | 19 (14) | 10 (9) | .26 |

| Treatment-related without NHL | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | |

| Second cancer | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| Cardiac | 8 (6) | 8 (8) | |

| Intercurrent disease | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| Unknown* | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| Total | 138 | 107 | .03 |

| Cause of death . | PAdriaCEBO, no. (%) . | PMitCEBO, no. (%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHL | 100 (72) | 84 (79) | .30 |

| Treatment-related with NHL | 19 (14) | 10 (9) | .26 |

| Treatment-related without NHL | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | |

| Second cancer | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| Cardiac | 8 (6) | 8 (8) | |

| Intercurrent disease | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| Unknown* | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| Total | 138 | 107 | .03 |

NHL indicates non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Treatment received

Patients receiving PMitCEBO received significantly more treatment than patients receiving PAdriaCEBO (Table5).

Treatment received

| Drug . | PACEBO total dosage (mg) . | PMitCEBO5-150 total dosage (mg) . | P value5-151 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthracycline | |||

| Median | 224 | 240 | .015 |

| Range | 15-461 | 35-624 | |

| Cyclophosphamide | |||

| Median | 2000 | 2062 | .02 |

| Range | 300-3960 | 300-3780 | |

| Etoposide | |||

| Median | 977 | 1031 | .03 |

| Range | 0-1918 | 0-1890 | |

| Bleomycin | |||

| Median | 64 | 68 | .02 |

| Range | 0-126 | 0-184 | |

| Vincristine | |||

| Median | 8 | 8 | .09 |

| Range | 0-72 | 0-104 |

| Drug . | PACEBO total dosage (mg) . | PMitCEBO5-150 total dosage (mg) . | P value5-151 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthracycline | |||

| Median | 224 | 240 | .015 |

| Range | 15-461 | 35-624 | |

| Cyclophosphamide | |||

| Median | 2000 | 2062 | .02 |

| Range | 300-3960 | 300-3780 | |

| Etoposide | |||

| Median | 977 | 1031 | .03 |

| Range | 0-1918 | 0-1890 | |

| Bleomycin | |||

| Median | 64 | 68 | .02 |

| Range | 0-126 | 0-184 | |

| Vincristine | |||

| Median | 8 | 8 | .09 |

| Range | 0-72 | 0-104 |

The actual dose of mitoxantrone given has been multiplied by 5 to enable the comparison with adriamycin to be made.

Mann-Whitney test.

Toxicity

Toxicities graded according to the common toxicity criteria are listed in Tables 6 and7. There was significantly more leucopenia and thrombocytopenia in the patients receiving PAdriaCEBO (P = 0.02 and P = 0.008, respectively); however, clinically significant infections were not different. There were no other clinically significant differences in toxicity between the 2 groups.

Hematologic toxicity

| Type and grade . | PAdriaCEBO . | PMitCEBO . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| White cell count | |||

| 0-2 | 90 | 67 | |

| 3-4 | 125 | 151 | .02 |

| Unknown | 44 | 39 | |

| Platelets | |||

| 0-2 | 181 | 200 | |

| 3-4 | 23 | 8 | .008 |

| Unknown | 55 | 49 | |

| Infections | |||

| 0-2 | 234 | 241 | |

| 3-4 | 25 | 16 | .20 |

| Type and grade . | PAdriaCEBO . | PMitCEBO . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| White cell count | |||

| 0-2 | 90 | 67 | |

| 3-4 | 125 | 151 | .02 |

| Unknown | 44 | 39 | |

| Platelets | |||

| 0-2 | 181 | 200 | |

| 3-4 | 23 | 8 | .008 |

| Unknown | 55 | 49 | |

| Infections | |||

| 0-2 | 234 | 241 | |

| 3-4 | 25 | 16 | .20 |

Other toxicities

| Type and grade . | PAdriaCEBO . | PMitCEBO . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alopecia | |||

| 0-2 | 184 | 199 | |

| 3-4 | 75 | 58 | .12 |

| Mucositis | |||

| 0-2 | 245 | 248 | |

| 3-4 | 14 | 9 | .40 |

| Nausea/vomiting | |||

| 0-2 | 243 | 245 | |

| 3-4 | 16 | 12 | .57 |

| Diarrhea | |||

| 0-2 | 251 | 252 | |

| 3-4 | 8 | 7 | .99 |

| Neurologic | |||

| 0-2 | 255 | 256 | |

| 3-4 | 4 | 1 | .37 |

| Skin | |||

| 0-2 | 251 | 257 | |

| 3-4 | 8 | 0 | .007 |

| Type and grade . | PAdriaCEBO . | PMitCEBO . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alopecia | |||

| 0-2 | 184 | 199 | |

| 3-4 | 75 | 58 | .12 |

| Mucositis | |||

| 0-2 | 245 | 248 | |

| 3-4 | 14 | 9 | .40 |

| Nausea/vomiting | |||

| 0-2 | 243 | 245 | |

| 3-4 | 16 | 12 | .57 |

| Diarrhea | |||

| 0-2 | 251 | 252 | |

| 3-4 | 8 | 7 | .99 |

| Neurologic | |||

| 0-2 | 255 | 256 | |

| 3-4 | 4 | 1 | .37 |

| Skin | |||

| 0-2 | 251 | 257 | |

| 3-4 | 8 | 0 | .007 |

Discussion

The management of elderly patients with HGL requires special consideration because of the increased risk of toxicity and death from treatment and disease. Initiatives to improve cytotoxic delivery without compromising benefit have led investigators to develop weekly, multiagent chemotherapy regimens.20-23,25,36-55Improvements in supportive care enable the delivery of chemotherapy at standard doses and intensity to deliver maximum benefit to patients.56 The minimum age of entry of 60 was chosen because patients younger than this were eligible for high-dose regimens and because this age carried prognostic significance in the international prognostic index (IPI) analyses.

In the BNLI randomized trial conducted in patients of all ages with stage II-IV HGL, treatment with PACEBOM was comparable with the CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone) regimen: CR rate of 64% (vs CHOP, 57%; P = ns) and an actuarial overall survival at 4 years of 61% (vs CHOP, 54%;P = ns).26 The current trial was designed to compare response rates, disease-free survival, overall survival, and toxicity between adriamycin and mitoxantrone in the PACEBOM regimen modified for elderly patients. The ratio of mitoxantrone to doxorubicin dose was based on the interim analyses of concurrent trials examining the same issue.24 27-30

In this study, the overall response rates were superior for elderly patients with HGL receiving PMitCEBO compared with PAdriaCEBO (Table2). Both rates compare favorably with other randomized studies in elderly patients as well as the standard CHOP chemotherapy regimen.24,27,29,57-59 The data from this trial confirm the finding from The International Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project (IPI) that patients older than 60 years had CR rates that were similar to those observed in younger patients.12

Patients in the mitoxantrone arm had significantly better overall survival and trend for improved cause-specific survival, reflecting durable remissions after chemotherapy in this group (Figures 2-4). The IPI retrospective analysis reported that the prognostic factors impacted on lower rates of complete responses and higher rates of relapse.12 Relapse rates at 2 years are 64% and 69% for PAdriaCEBO and PMitCEBO, respectively, and at 4 years are 38% and 58% for PAdriaCEBO and PMitCEBO, respectively. These rates compare favorably with those seen in the Dutch Hemato-Oncology Study Group trial of mitoxantrone substitution for adriamycin in elderly patients with HGL.24 Partial and NPPR rates were similar between the 2 arms, excluding slow responses as a cause for poorer prognosis.60

The age for inclusion in this trial was chosen in order to maintain consistency with trials examining the role of high-dose chemotherapy in younger patients with poor prognostic features and because this was the discriminating value reported in the IPI study. The multivariate model based on tumor stage, serum LDH, and performance status was not significantly different between the 2 treatment groups in this trial. Gómez and colleagues retrospectively analyzed a cohort of elderly (older than 60 years) patients with aggressive NHL who received treatment with adriamycin-based chemotherapy. They reported that the risk of treatment-related death was associated with poor performance status and not with increasing age.61 A recent retrospective analysis of IPI factors using an extension of the Cox proportional hazards model in patients younger than 60 years with aggressive NHL identified performance status as the only predictive factor for survival during the first 3 months of therapy.62 In this trial treatment, age, stage, and performance status carried prognostic significance. Differences in patient characteristics between the 2 trial arms were not seen and therefore cannot account for the superior activity of PMitCEBO.

Treatment with either regimen was well tolerated in both groups with acceptable hematologic and nonhematologic toxicities as well as comparable treatment-related death rates. There were no differences in cardiac or infectious complications that may have affected survival in this elderly population.

There is no evidence to support increased response rates with weekly mitoxantrone as a single agent63,64; however, several groups have examined its role in combination regimens. Zinzani and colleagues have reported their results of a regimen similar to PMitCEBO, called VNCOP-B, in elderly patients with aggressive NHL. They treated 29 patients with cyclophosphamide, 250 mg/m2, and mitoxantrone, 10 mg/m2, delivered on weeks 1, 3, 5, and 7; vincristine, 2 mg administered on weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8; etoposide, 100 mg/m2 administered on weeks 2 and 6; bleomycin, 8 mg/m2 administered on weeks 4 and 8; and prednisone, 40 mg given intramuscularly daily throughout therapy.46 They reported 22 CRs (76%), an overall response rate of 93% and, after a median of 13 months of follow-up, overall survival of 75%. These results support the use of short-duration weekly combination chemotherapy regimens for elderly patients with HGL. Phase II trials of less aggressive regimens have less toxicity at the expense of reduced response rates.23

Mitoxantrone has been substituted for adriamycin in combination chemotherapy regimens for a variety of malignancies because of good activity and reduced toxicity at equivalent levels of bone marrow suppression and with a milligram-to-milligram ratio of approximately 5:1.65 Several groups have undertaken randomized comparisons of mitoxantrone substituted for adriamycin in patients with HGL. Elderly patients (older than 60 years) receiving CHOP had superior CR rates and lymphoma-specific and overall survival rates compared with patients receiving CNOP.24 In the trial by Bezwoda et al, patients receiving CNOP had faster times to CR and nearly double the median relapse-free survival compared with patients receiving CHOP.59 Other groups have not been able to demonstrate any differences in response rates or survival in their trials, which included patients of all ages.27-29,57 66

A possible reason for an improved drug regimen is that the drugs are better tolerated and a greater proportion of the planned dose intensity is actually given.67-69 In Table 5, it is apparent that significantly more of nearly all drugs were administered in the PMitCEBO arm, but this, of course, is confounded by the fact that the lower response rate with PACEBO led to earlier discontinuation of this therapy. After 4 weeks, for instance, the anthracycline and cyclophosphamide delivered was the same in both arms (data not shown). The issue of dose intensity cannot be accurately addressed because of the way in which the date of chemotherapy administration was recorded.

In conclusion, the PMitCEBO arm resulted in a significant improvement in lymphoma control although the reasons for this are not fully clear. If a weekly schedule of combination chemotherapy is used to treat elderly patients with HGL, it is preferable to use an anthracenedione such as mitoxantrone than an anthracycline such as doxorubicin. These results compare favorably with other polychemotherapy regimens used in the elderly.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

David Cunningham, Royal Marsden Hospital, Downs Rd, Sutton Surrey SM25PT, United Kingdom; e-mail: dcunn@icr.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal