Abstract

A retrospective study was performed to collect information regarding efficacy and toxicity of cidofovir (CDV) in allogeneic stem cell transplant patients. Data were available on 82 patients. The indications for therapy were cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease in 20 patients, primary preemptive therapy in 24 patients, and secondary preemptive therapy in 38 patients. Of the patients, 47 had received previous antiviral therapy with ganciclovir, foscarnet, or both drugs. The dosage of CDV was 1 to 5 mg/kg per week followed by maintenance every other week in some patients. The duration of therapy ranged from 1 to 134 days (median, 22 days). All patients received probenecid and prehydration. Ten of 20 (50%) patients who were treated for CMV disease (9 of 16 with pneumonia) responded to CDV therapy, as did 25 of 38 (66%) patients who had failed or relapsed after previous preemptive therapy and 15 of 24 (62%) patients in whom CDV was used as the primary preemptive therapy. Of the patients, 21 (25.6%) developed renal toxicity that remained after cessation of therapy in 12 patients. Fifteen patients developed other toxicities that were potentially due to CDV or the concomitantly given probenecid. No toxicity was seen in 45 (61.6%) patients. Cidofovir can be considered as second-line therapy in patients with CMV disease failing previous antiviral therapy. However, additional studies are needed before CDV can be recommended for preemptive therapy.

Introduction

Viral infections are major complications after allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT). Despite advances in the management of cytomegalovirus (CMV) during the last decade, the morbidity and mortality for patients receiving mismatched or unrelated transplants are still substantial.1 Cidofovir (CDV) is a nucleotide analogue with broad in vitro antiviral activity, for example, against CMV and adenovirus. It has advantages, such as a pharmacokinetic profile allowing once-a-week dosing, and studies have shown efficacy against CMV retinitis in human immunodeficiency virus–infected patients.2-4However, the toxicity profile of the drug, most importantly, nephrotoxicity, has limited its use in SCT recipients. The aim of this retrospective study was to collect information regarding efficacy and toxicity in allogeneic SCT patients treated with CDV.

Patients and methods

Survey

This was a retrospective survey among centers belonging to the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). First, a survey was sent to all member centers asking whether the center had used CDV in allogeneic SCT patients. A second questionnaire was sent to those centers that had used CDV for any indication. The second questionnaire included questions regarding patient characteristics, indication for therapy, dosage and duration of CDV therapy, previous antiviral therapy, concurrent other nephrotoxic drug therapy, and outcome. Ethical committee approval for this study was obtained at each center as required.

Because this was a multicenter retrospective study, each center followed its own guidelines for CMV prevention and monitoring. Either antigenemia or qualitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for CMV DNA (DNAemia) was used for guiding the initiation and efficacy of preemptive therapy as previously described.5-9

Patients

Patient and transplantation baseline information is presented in Table 1. The study enrolled 82 patients from 17 centers treated with CDV for CMV disease or given as preemptive therapy. The indications for therapy were the following:

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic . | All patients N = 82 . | CMV disease N = 20 . | Preemptive therapy . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary N = 24 . | Secondary N = 38 . | |||

| Median age, years (range) | 34.7 (0.3-57.7) | 32.3 (0.3-59.0) | 40.9 (17.9-57.5) | 29.8 (0.5-50.9) |

| Donor type | ||||

| Unrelated | 41 | 8 | 14 | 19 |

| Phenotypically identical family donor | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| HLA-identical sibling donor | 29 | 7 | 9 | 13 |

| Mismatched family donor | 10 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Graft type | ||||

| Bone marrow | 39 | 9 | 5 | 25 |

| Peripheral blood stem cells | 42 | 10 | 19 | 13 |

| Cord blood cells | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Acute GVHD | ||||

| Grade 0-I | 44 | 10 | 18 | 16 |

| Grade II-IV | 38 | 10 | 6 | 22 |

| Previous antiviral therapy | ||||

| GCV | 13 | 3 | 0 | 10 |

| Foscarnet | 12 | 3 | 0 | 9 |

| Both GCV and foscarnet | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1* |

| GCV combined with foscarnet | 25 | 6 | 0 | 19* |

| No previous therapy | 30 | 6 | 24 | 0 |

| Characteristic . | All patients N = 82 . | CMV disease N = 20 . | Preemptive therapy . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary N = 24 . | Secondary N = 38 . | |||

| Median age, years (range) | 34.7 (0.3-57.7) | 32.3 (0.3-59.0) | 40.9 (17.9-57.5) | 29.8 (0.5-50.9) |

| Donor type | ||||

| Unrelated | 41 | 8 | 14 | 19 |

| Phenotypically identical family donor | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| HLA-identical sibling donor | 29 | 7 | 9 | 13 |

| Mismatched family donor | 10 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Graft type | ||||

| Bone marrow | 39 | 9 | 5 | 25 |

| Peripheral blood stem cells | 42 | 10 | 19 | 13 |

| Cord blood cells | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Acute GVHD | ||||

| Grade 0-I | 44 | 10 | 18 | 16 |

| Grade II-IV | 38 | 10 | 6 | 22 |

| Previous antiviral therapy | ||||

| GCV | 13 | 3 | 0 | 10 |

| Foscarnet | 12 | 3 | 0 | 9 |

| Both GCV and foscarnet | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1* |

| GCV combined with foscarnet | 25 | 6 | 0 | 19* |

| No previous therapy | 30 | 6 | 24 | 0 |

CMV indicates cytomegalovirus; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; GCV, ganciclovir.

One patient received both GCV and foscarnet, first separately and then in combination.

CMV disease.

There were 20 patients treated for CMV disease. Of these patients, 16 had CMV pneumonia (combined with gastrointestinal disease in 1 patient); 3 patients had CMV gastrointestinal disease (combined in 1 patient with hepatitis and in 1 patient with encephalitis); and 1 patient had hepatitis.

Preemptive therapy.

CDV was given to 24 patients as first-line preemptive therapy. For 38 patients, CDV was given as second-line preemptive therapy because of either failure of other antiviral therapy (20 patients) or relapse of CMV infection (18 patients).

CDV therapy

The dosage of CDV was 1 mg/kg per dose in 1 patient, 3 mg/kg per dose in 24 patients, 4.5 mg/kg per dose in 1 patient, and 5 mg/kg per dose in 48 patients. The dosing schedule varied, but most patients received 2 initial doses with a 1-week interval between doses and thereafter maintenance doses every other week. For 65 patients, cyclosporine was given concurrently with CDV; 3 patients received tacrolimus; and 40 patients received other potentially nephrotoxic agents (34 together with cyclosporine and 2 together with tacrolimus).

There were 50 patients who had received previous antiviral therapy (Table 1). CDV therapy was combined with foscarnet in 5 patients and with ganciclovir (GCV) in 2 patients.

Definitions

CMV disease was defined according to published recommendations.10 A diagnosis of CMV pneumonia required signs or symptoms of lower respiratory disease (hypoxemia, radiographic changes) together with the virus isolated from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) or lung tissue. Gastrointestinal disease required symptoms together with lesions detected at endoscopy and the virus detected from biopsy material by culture, histopathology, immunohistochemistry, or DNA hybridization. Hepatitis required an abnormal liver function together with the virus detected from biopsy material. CNS disease required symptoms together with the virus detected by culture or PCR from cerebrospinal fluid.

Failure of preemptive therapy was defined as continued presence of pp65 antigenemia or DNAemia and relapse after first-line preemptive therapy, defined as recurrence of either pp65 antigenemia or DNAemia after at least 1 week of antiviral therapy.

The outcome of CDV therapy was defined in one of the following ways:

Response.

Disease regression without addition of other specific therapy or, for preemptive therapy, conversion of a positive test signal (antigenemia or PCR) to a negative signal that remained negative for at least 2 weeks after discontinuation of therapy.

Possible response.

Death from another cause, but with the signs of originally treated disease having decreased at the time of death.

Failure.

Death due to CMV disease more than 3 days after introduction of therapy, progression to disease during preemptive therapy, or change to other specific antiviral therapy owing to failure to convert a positive test signal to a negative signal.

Nonevaluable.

Death from CMV disease within 3 days of initiation of therapy, or death from another cause within 7 days of therapy initiation and before evaluation of the treatment could be performed.

Statistics

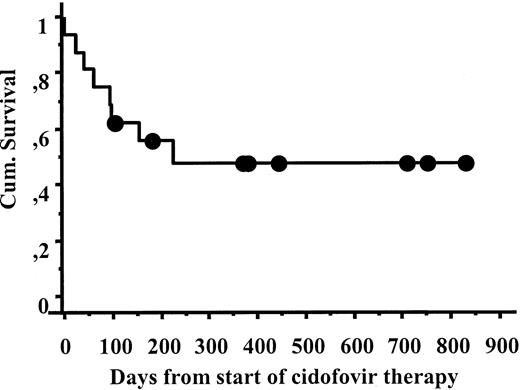

For comparisons of characteristics among different patient groups, either Fisher exact test (2-tailed) or Mann-Whitney test (2-tailed) was used. Survival of patients with CMV pneumonia was calculated by means of the Kaplan-Meier technique.

Results

Toxicity

Of the 82 patients, 49 (59.8%) experienced no toxicity; 21 patients (25.6%) developed renal toxicity, defined as a rise in the serum creatinine of at least 1.5 × baseline or development of proteinuria; and 5 patients had at least 2-fold increases in the serum creatinine. Of 62 patients, 9 (14.5%) developed signs of tubular toxicity. After cessation of therapy, 9 patients still fulfilled the definitions for renal toxicity.

Severe renal toxicity occurred in 5 patients. Three patients developed renal failure and 3 additional patients developed significant tubulopathy requiring substitution with bicarbonate and electrolytes. Of these 6 patients, 4 received concomitant foscarnet. Of 3 patients who developed renal failure, 2 already had severely impaired renal function prior to starting CDV treatment.

Dialysis was required by 2 patients. Both of these patients later died, one from CMV pneumonia and the other from generalized adenovirus infection. The third patient with renal failure died 1 day after the first dose of CDV from CMV interstitial pneumonia. All 3 patients who developed significant tubulopathy are alive, and 2 patients have improving renal function with decreasing requirements for electrolyte substitution.

Of 21 patients who developed renal toxicity, 18 had received previous antiviral therapy. Excluding the 4 patients who received concomitant foscarnet, renal toxicity developed in 4 of 12 patients who had received GCV, 4 of 7 who had received foscarnet, and 6 of 27 who had received both drugs before starting therapy with CDV.

Patients treated for CMV disease had a higher risk of renal toxicity than patients receiving CDV as preemptive therapy. The frequencies of renal toxicity were 35%, 29%, and 12% in patients receiving CDV for CMV disease, secondary preemptive therapy, and primary preemptive therapy, respectively.

There was no correlation between dosage of CDV and renal toxicity. Of 55 patients treated with 5 mg/kg per dose, 15 developed renal toxicity; in 6 of these patients, the toxicity persisted after therapy. Table2 gives additional data on these 2 dosage groups. For patients treated with 3 mg/kg per dose, 5 developed renal toxicity, and in 2 of these, the toxicity persisted after therapy. Renal toxicity seemed to occur early during CDV therapy. Of 36 patients treated for 21 days or fewer, 12 patients developed renal toxicity, compared with 9 of 46 patients treated for 22 days or longer. This finding is presumably due to the early discontinuation of therapy in patients showing signs of renal toxicity.

Dosage of cidofovir and toxicity

| . | Patients receiving CDV 3 mg/kg n = 24 . | Patients receiving CDV 4.5 to 5 mg/kg n = 56 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (range) of therapy duration (weeks) | 2.5 (1-9) | 3 (1-26) | NS |

| No. (proportion) of patients receiving concomitant nephtotoxic drugs | |||

| Cyclosporine | 22 (91.6%) | 43 (76.7%) | .09 |

| Tacrolimus | 1 (4.1%) | 2 (3.6%) | NS |

| Other nephrotoxic drugs | 8 (33.3%) | 31 (55.4%) | .08 |

| Median baseline s-creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.07 | 0.8 | .04 |

| No. (proportion) of patients who developed nephrotoxicity defined as: | |||

| >1.5 ≤ 2.0 × baseline s-creatinine | 2/24 | 4/56 | NS |

| ≥2.0 × baseline s-creatinine | 2/24 | 3/56 | NS |

| Renal failure | 0/24 | 1/56 | NS |

| Proteinuria | 1/24 | 10/56 | NS |

| Nausea/vomiting | 0/24 | 6/56 | .09 |

| Rash | 2/24 | 0/56 | NS |

| Ophthalmological toxicity | 2/24 | 0/56 | NS |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0/24 | 2/56 | NS |

| . | Patients receiving CDV 3 mg/kg n = 24 . | Patients receiving CDV 4.5 to 5 mg/kg n = 56 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (range) of therapy duration (weeks) | 2.5 (1-9) | 3 (1-26) | NS |

| No. (proportion) of patients receiving concomitant nephtotoxic drugs | |||

| Cyclosporine | 22 (91.6%) | 43 (76.7%) | .09 |

| Tacrolimus | 1 (4.1%) | 2 (3.6%) | NS |

| Other nephrotoxic drugs | 8 (33.3%) | 31 (55.4%) | .08 |

| Median baseline s-creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.07 | 0.8 | .04 |

| No. (proportion) of patients who developed nephrotoxicity defined as: | |||

| >1.5 ≤ 2.0 × baseline s-creatinine | 2/24 | 4/56 | NS |

| ≥2.0 × baseline s-creatinine | 2/24 | 3/56 | NS |

| Renal failure | 0/24 | 1/56 | NS |

| Proteinuria | 1/24 | 10/56 | NS |

| Nausea/vomiting | 0/24 | 6/56 | .09 |

| Rash | 2/24 | 0/56 | NS |

| Ophthalmological toxicity | 2/24 | 0/56 | NS |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0/24 | 2/56 | NS |

CDV indicates cidofovir; s-creatinine, serum creatinine.

Other side effects potentially associated with CDV therapy were nausea and vomiting in 6 patients, thrombocytopenia in 2, and ophthalmologic toxicity in 2 patients. Dizziness, syncope, and neurotoxicity occurred in 1 patient each. Two patients developed allergic skin reactions that possibly were due to probenecid.

Clinical and virological responses to CDV therapy

Table 3 shows the outcome for patients treated with CDV for either CMV disease or as primary or secondary preemptive therapy.

Outcome of CDV therapy

| Indication for therapy . | No. treated . | Response (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| CMV pneumonia | 16 | 9/16 (56) |

| Other CMV disease | 4 | 1/4 (25) |

| Secondary preemptive therapy | 38 | 26/38 (68) |

| Failure | 20 | 11/20 (55) |

| Relapse | 18 | 15/18 (83) |

| Primary preemptive therapy | 26 | 15/26 (58) |

| Indication for therapy . | No. treated . | Response (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| CMV pneumonia | 16 | 9/16 (56) |

| Other CMV disease | 4 | 1/4 (25) |

| Secondary preemptive therapy | 38 | 26/38 (68) |

| Failure | 20 | 11/20 (55) |

| Relapse | 18 | 15/18 (83) |

| Primary preemptive therapy | 26 | 15/26 (58) |

CMV indicates cytomegalovirus.

Of 16 patients with CMV pneumonia, 9 responded to CDV and 2 had possible responses. The 30-day survival from the start of CDV therapy was 87%, and the 6-month survival 55% (Figure1). CDV was given to 11 patients after failure of other antiviral therapy. Of these patients, 6 survived; 1 had a possible response; 1 was not evaluable; and 3 failed CDV and either died or changed to other therapy. Among the 5 patients who had not received previous antiviral therapy, 3 patients responded, 1 patient had a possible response, and 1 patient failed. The causes of death within 6 months of CDV therapy were CMV pneumonia (3), aspergillosis (2), leukemia relapse (1), and heart failure (1).

The response rates were 66% and 68% for CDV as primary and secondary preemptive therapy, respectively.

There were 4 patients treated for other types of CMV disease. Of these patients, 1 responded; 2 had possible responses but died from other causes (GVHD, EBV lymphoma); and 1 developed CMV pneumonia and died.

Discussion

Despite substantial advances in the prevention of CMV infection after allogeneic SCT, many patients still need antiviral therapy, either as preemptive therapy to prevent the development of CMV disease or for therapy of CMV disease that has developed despite preventive measures.

There are 2 antiviral agents currently available for treatment of CMV infection in SCT patients: GCV and foscarnet. GCV is the treatment of choice for CMV pneumonia and is usually given together with intravenous immune globulin.11-15 Both GCV and foscarnet have been used for therapy of other types of CMV disease.16-19 The combination of GCV and foscarnet has also been used both for treatment of CMV disease and as preemptive therapy in high-risk patients.20

Preemptive therapy is increasingly used as prevention against CMV disease. Both GCV and foscarnet have been used and been shown to be effective in preventing CMV disease, particularly when pp65 antigenemia or PCR was used for monitoring.5,7,8,21-23 However, GCV is associated with significant bone marrow toxicity that may predispose to severe bacterial and fungal infections,24,25 and foscarnet can cause significant renal toxicity and electrolyte disturbances.5,17,26 27

CDV is a nucleotide analogue with broad antiviral activity, which has been shown to be effective against CMV retinitis refractory to other antiviral therapy in AIDS patients.2-4 CDV has some attractive features for use in allogeneic SCT patients. Its therapeutic spectrum includes CMV, herpes simplex virus (including acyclovir-resistant strains), varicella-zoster virus, human herpesvirus 6, papovavirus, and adenovirus, all of which are recognized pathogens in allogeneic SCT recipients. Furthermore, although CDV can be given only intravenously, its pharmacokinetic properties allow once-a-week dosing. However, the drug's toxicity profile has until now limited its use in allogeneic SCT patients. CDV is associated with nephrotoxicity, in particular tubular toxicity. The risk for nephrotoxicity can be reduced, however, by the use of concomitant probenecid and prehydration. In 2 studies, Lalezari et al2,3 reported 12% to 39% proteinuria and 24% increases in the serum creatinine despite these protective measures. Other important side effects reported from the studies in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients are bone marrow suppression and ophthalmologic toxicity. Lalezari et al3 found 15% asymptomatic neutropenia in one randomized study in AIDS patients. Several authors have reported ophthalmologic side effects from CDV.28-32 These include uveitis, iritis, and ocular hypotonia and were reported in up to 44% of the patients. Risk factors reported as being associated with ophthalmologic side effects were increased serum creatinine, diabetes mellitus, treatment of retinitis, and use of protease inhibitors29,32 whereas the use of probenecid was protective.32

Until now, only a single case report has been published regarding the use of CDV after allogeneic SCT33 although small pilot studies have been presented at scientific meetings. We therefore performed a retrospective survey among centers belonging to the EBMT to gather data on the current experience with CDV and particularly to assess its toxicity. It must be recognized that assessment of toxicity is difficult in retrospective studies. Renal toxicity was assessed both as increased serum creatinine and development of proteinuria. Overall, renal toxicity developed in 25.6% of the patients; a proportion similar to that seen in AIDS patients given prophylactic hydration and probenecid.2 3 This is encouraging since 72 of the 82 patients received additional nephrotoxic agents. More severe renal toxicity developed in 5 patients (2 of these developed renal failure and 3 significant tubulopathy). However, 4 of these patients had received concomitant foscarnet—another antiviral agent that can cause significant renal toxicity. Thus, the combination of CDV and foscarnet should definitely be avoided.

Marrow toxicity was rarely reported in this retrospective series. Only 2 patients developed thrombocytopenia, assessed by the investigator as probably due to CDV. Finally, only 2 patients (2.7%) developed ophthalmologic toxicity. This is a substantially lower proportion than what has been reported in AIDS patients.29 32 There might be several reasons for this low frequency in our study. First, most of our patients did not have the risk factors associated with ophthalmologic toxicity in the studies in AIDS patients, and all were given probenecid. However, it is also possible that this type of toxicity was underestimated in our patient series since no regular ophthalmologic examinations were performed unless the patients complained of symptoms from the eyes.

Toxicity should be assessed both in relation to the indication for therapy and the toxicity of alternative agents. Clearly, toxicity as seen in this survey is of minor consequence in patients with CMV pneumonia in whom other antiviral agents have failed. However, in patients receiving preemptive therapy, the situation is different. The marrow toxicity was substantially less than what would be expected with GCV. On the other hand, renal toxicity was more frequent than in the recent randomized study comparing GCV and foscarnet.34Therefore, we believe that randomized, comparative studies are indicated before CDV is introduced as an accepted agent for first-line preemptive therapy.

The results of our retrospective survey show that CDV effectively treats CMV infections and disease in allogeneic SCT patients. The results concerning CMV pneumonia are particularly interesting. CMV pneumonia is still a very serious disease with mortality of at least 50%.12 15 In this small series, 9 of 16 patients (56%) treated for CMV interstitial pneumonia survived even though 6 of these 9 patients had previously failed therapy with GCV, foscarnet, or both. The reason for this good response rate is unknown but effects on other viruses simultaneously present in lung tissue could be possible. Alternatively, since cross-resistance between CDV, GCV, and foscarnet is rare, this could be due to an effect on CMV, which was resistant to the antiviral agent initially used. It could be argued that the selection of patients was biased since the survey was retrospective, and we cannot refute that possibility. However, we believe the data are interesting enough to warrant further study of CDV as therapy of CMV disease.

CDV was also effective as secondary preemptive therapy, both in patients failing antiviral therapy (55% response) and in patients relapsing after therapy with GCV, foscarnet, or both (83%). No study of secondary preemptive therapy has been published, and therefore it is difficult to assess how these results compare with those on patients treated with other antiviral agents. Finally, 58% of the patients, given CDV as up-front preemptive therapy, responded. These results are comparable with published results for GCV or foscarnet.7,22,23 Reusser et al34 recently presented data from a randomized study comparing foscarnet and GCV. The results from this study are also comparable to those obtained in patients given CDV as up-front preemptive therapy.

From this retrospective study, we conclude that CDV can be effective in treatment of CMV infection and disease after allogeneic SCT and can be given with an acceptable risk of toxicity. CDV can be considered in patients with CMV disease, in particular in patients failing on therapy with GCV or foscarnet, and as second-line preemptive therapy.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Note added in proof

Fourteen patients treated with cidofovir as primary preemptive therapy are also included in a paper to be published inTransplantation by Platzbecker et al.

Author notes

Per Ljungman, Department of Hematology, Huddinge University Hospital, SE-14186 Stockholm, Sweden; e-mail:per.ljungman@medhs.ki.se.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal