Abstract

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) responses can be generated against peptides derived from the immunoglobulin (Ig) V region in some but not all patients. The main reason for this appears to be the low peptide-binding affinity of Ig-derived peptides to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules and their resulting low immunogenicity. This might be improved by conservative amino acid modifications at the MHC-binding residues of the peptides (heteroclitic peptides). In this study, it was found that in 18 Ig-derived peptides, that heteroclitic peptides from the Ig gene with improved binding to human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A*0201 can be used to improve CTL responses. Amino acid substitution substantially increased predicted binding affinity, and there was a strong correlation between predicted and actual binding to HLA-A*0201. CTLs generated against the heteroclitic peptide had not only enhanced cytotoxicity against the heteroclitic peptide but also increased killing of antigen-presenting cells pulsed with the native peptide. Surprisingly, no difference was observed in the frequency of T cells detected by MHC class I peptide tetramers after stimulation with the heteroclitic peptide compared with the native peptide. CTLs generated against heteroclitic peptides could kill patients' tumor cells, showing that Ig-derived peptides can be presented by the tumor cell and that the failure to mount an immune response (among other reasons) likely results from the low immunogenicity of the native Ig-derived peptide. These results suggest that heteroclitic Ig-derived peptides can enhance immunogenicity, thereby eliciting immune responses, and that they might be useful tools for enhancing immunotherapy approaches to treating B-cell malignant diseases.

Introduction

Most B-cell malignant diseases are characterized by clonal expansion of a single B cell. The B-cell–antigen receptor, the immunoglobulin (Ig), is a clonal marker containing tumor-specific epitopes, or idiotypes, that can function as targets for T-cell–mediated immune responses.1-4 In murine lymphoma models, humoral and cellular mechanisms against idiotypes are effective in inducing tumor regression in tumor-bearing hosts.4-8 In clinical trials, vaccination with patient-specific Ig has shown efficacy, with predominantly humoral immune responses reported.9,10 Several studies indicated that vaccination with idiotype elicits CD4+ and CD8+ responses in vitro and in vivo.11-14 However, analysis of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I–restricted CD8+T-cell responses in the patients did not find the Ig-derived epitopes recognized by tumor-specific T cells.15,16 Previously, we and others showed that CD8+ T-cell responses against Ig-derived peptides can be generated and that such cells are capable of killing the primary tumor cells from which the Ig was derived.17 18

CD8+ T lymphocytes recognize small peptides (9-10 amino acids in length) presented on the surface of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) by MHC class I molecules. Several tumor antigens have been identified on the basis of gene cloning or sequencing of the naturally presented peptide eluted from MHC class I molecules.19-21MHC class I–restricted antigenic peptides have the potential to be candidates for tumor vaccines and have been tested in animal models and humans. However, results obtained with such peptide vaccines have been variable.22 Successful immunization was obtained after vaccination with peptides derived from a mutated connexin 37 gap–junction protein expressed on murine carcinoma, with regression of established metastases.23 Protective immune responses were obtained against viruses after peptide vaccination in one study24 but, in other models, peptide vaccines had limited or negative results.25-27

One reason for the limited immunogenicity of some tumor-derived peptides is weak binding of the peptide to the MHC molecule. The requirements for peptides to bind to human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules and to elicit cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) responses have been studied extensively.28-32 The strength of CTL responses depends on the binding affinity of the target peptide to HLA class I, the stability of the peptide–HLA complex, and the avidity of T-cell receptor (TCR) binding for the peptide complex.33-35 Most virus-derived immunodominant peptides have high binding affinity or peptide–HLA complex stability.33 Peptides with such characteristics can be predicted on the basis of well-established binding motifs for the most common HLA alleles.29,32 This technique has been applied to the identification of CTL epitopes derived from melanoma antigen (MAGE) 3,36 proteinase 3,37 and telomerase.38 However, using this approach in a study with Ig V region–derived peptides, we found that only 14 of 794 peptides showed strong binding to HLA-A*0201, the most common HLA class I allele. More than 90% of the analyzed peptides showed absent or only weak MHC binding.17 Therefore, one likely reason for the weakness of CTL responses against the Ig of the tumor cell is the low immunogenicity of Ig-derived MHC class I–restricted peptides.

One strategy to increase MHC binding and immunogenicity of low-binding peptides is to modify the peptide at the MHC-binding amino acid residues while leaving the T-cell–recognition residues intact.39 The resultant “heteroclitic” peptides were previously shown to lead to improved induction of CTL responses against melanoma in murine models40 and trials in humans.41 We here report that heteroclitic peptides from the Ig V region with improved binding to HLA-A*0201 can be used to induce a CTL response. Importantly, heteroclitic peptides elicited T-cell responses against not only the altered peptide but also against the native peptide from which they were derived, and they also increased the efficacy of killing of primary leukemic cells. This strategy might not only increase the pool of peptides that can be used to generate T-cell responses against B-cell malignant diseases but may also be used to increase the efficiency of tumor-cell killing.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients and healthy donors

Peripheral blood and tumor samples were collected from healthy donors and patients at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and cryopreserved. Ig gene rearrangements from tumor cells were sequenced from patients with a variety of B-cell malignant diseases as previously described.17 All tumor samples used to test killing were obtained from patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). All specimens were obtained after informed consent and approval by our institutional review board were provided.

Peptide-prediction analysis and bioinformatics

Ig-deduced protein sequences were reviewed for peptides 9 and 10 amino acids long that could possibly bind to MHC class I molecules. Two independent computer prediction analyses were used (http://bimas.dcrt.nih.gov/molbio/hla_bind andhttp://134.2.96.221/Scripts/MHCServer.dll/EpPredict.htm) to examine the binding of native peptides to HLA-A*0201 molecules. The analysis used HLA-A*0201 because this MHC class I allele is expressed in approximately 50% of our patients. Heteroclitic peptides were designed in which conservative amino acid substitutions of the MHC-binding residues were expected to enhance the affinity toward the MHC class I allele, as predicted by using the computer algorithms.

Peptide synthesis

All native and heteroclitic peptides were generated by fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl synthesis (Sigma-Genosys Biotechnologies, The Woodlands, Texas). Purity was determined by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography and verified by mass spectral analysis. The peptides that were synthesized and assayed are shown in Table 1. Peptides were dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline at a concentration of 2 mg/mL and stored at −70°C until use. A peptide derived from MAGE 3 was used as a positive control.

Immunoglobulin-derived synthetic native and heteroclitic peptides

| Name . | Position . | Sequence . | Parker score . | Rammensee score . | FI . | CTLs induced/ donors tested . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FR9 | FR3 | TLFLQMNSL | 181 | 24 | 0.2 | 3/6 |

| FR9H | KLFLQMNSL | 636 | 25 | 0.2 | 1/1 | |

| FR13 | FR2 | CVLLCEIWV | 123 | 16 | Not available | Not tested |

| FR13H | KVLLCEIWV | 1935 | 23 | 0.6 | 2/2 | |

| FR15 | FR3 | NQFSLKLSSV | 60 | 17 | 0.9 | 1/6 |

| FR15H | NQFSLKLSSV | 591 | 27 | 2.0 | 1/3 | |

| FR16 | FR3 | SLQPEDFAT | 43 | 19 | 1.3 | 3/7 |

| FR16H | κ | SLQPEDFAV | 403 | 25 | 2.8 | 2/4 |

| FR17 | FR3 | YLQMNSLRA | 22 | 17 | 0.3 | 2/7 |

| FR17H | YLQMNSLRV | 320 | 23 | 1.8 | 3/3 | |

| FR18 | FR2 | QAPGKGLEWV | 6 | 20 | 0.4 | 0/5 |

| FR18H | QLPGKGLEWV | 431 | 26 | 1.3 | 2/2 | |

| FR21 | FR2 | APGKGLEWV | 3 | 18 | 0.1 | 2/6 |

| FR21H | ALGKGLEWV | 431 | 28 | 2.7 | 2/3 | |

| FR23 | FR3 | STAYMELSSL | 1 | 23 | 0.6 | 2/6 |

| FR23H | SLAYMELSSL | 49 | 29 | 1.4 | 2/3 | |

| FR24 | FR2 | FPGKGLVWV | 26 | 19 | 0.2 | 0/8 |

| FR24H | FLGKGLVWV | 4047 | 29 | 2.3 | 1/4 | |

| FR25 | FR3 | AVYLQMNSL | 14 | 20 | 0.1 | 0/8 |

| FR25H | AVYLQMNSV | 512 | 26 | 2.4 | 1/4 | |

| FR26 | FR3 | TLYLQMDNL | 77 | 21 | 0.6 | 0/5 |

| FR26H | KLYLQMDNV | 878 | 22 | 1.3 | 2/4 | |

| FR27 | FR3 | SVIAADTAV | 6 | 19 | 0.1 | 0/2 |

| FR27H | KVIAADTAV | 243 | 24 | 0.9 | 1/2 | |

| FR28 | FR3 | NQFTLKLTSV | 60 | 17 | 0.5 | 0/2 |

| FR28H | NLFTLKLTSV | 2071 | 28 | 1 | 0/2 | |

| FR29 | FR3 | NQFSLKLSSV | 60 | 17 | 0.3 | 0/2 |

| FR29H | KLFSLKLSSV | 2071 | 28 | 0.8 | 0/2 | |

| FR30 | FR3 | TLYLQMNSL | 157 | 24 | 0.1 | 0/2 |

| FR30H | KLYLQMNSV | 1792 | 25 | 0.5 | 1/2 | |

| FR31 | FR3 | AVYYCARDLV | 10 | 16 | 0.7 | 0/2 |

| FR31H | KVYYCARDLV | 382 | 21 | 0.09 | 1/2 | |

| CDR16 | CDRI | IVSDNCMSWV | 537 | 17 | 0.5 | 1/5 |

| CDR16H | ILSDNCMSWV | 6132 | 23 | 1.8 | 1/4 | |

| CDR17 | CDRII | KGLEWISGYI | 6 | 17 | 0.6 | 0/2 |

| CDR17H | KLLEWISGYV | 6072 | 29 | 1.3 | 1/2 | |

| MAGE | aa 271 | FLWGPRALV | 2655 | 27 | 2.6 | 12/12 |

| Name . | Position . | Sequence . | Parker score . | Rammensee score . | FI . | CTLs induced/ donors tested . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FR9 | FR3 | TLFLQMNSL | 181 | 24 | 0.2 | 3/6 |

| FR9H | KLFLQMNSL | 636 | 25 | 0.2 | 1/1 | |

| FR13 | FR2 | CVLLCEIWV | 123 | 16 | Not available | Not tested |

| FR13H | KVLLCEIWV | 1935 | 23 | 0.6 | 2/2 | |

| FR15 | FR3 | NQFSLKLSSV | 60 | 17 | 0.9 | 1/6 |

| FR15H | NQFSLKLSSV | 591 | 27 | 2.0 | 1/3 | |

| FR16 | FR3 | SLQPEDFAT | 43 | 19 | 1.3 | 3/7 |

| FR16H | κ | SLQPEDFAV | 403 | 25 | 2.8 | 2/4 |

| FR17 | FR3 | YLQMNSLRA | 22 | 17 | 0.3 | 2/7 |

| FR17H | YLQMNSLRV | 320 | 23 | 1.8 | 3/3 | |

| FR18 | FR2 | QAPGKGLEWV | 6 | 20 | 0.4 | 0/5 |

| FR18H | QLPGKGLEWV | 431 | 26 | 1.3 | 2/2 | |

| FR21 | FR2 | APGKGLEWV | 3 | 18 | 0.1 | 2/6 |

| FR21H | ALGKGLEWV | 431 | 28 | 2.7 | 2/3 | |

| FR23 | FR3 | STAYMELSSL | 1 | 23 | 0.6 | 2/6 |

| FR23H | SLAYMELSSL | 49 | 29 | 1.4 | 2/3 | |

| FR24 | FR2 | FPGKGLVWV | 26 | 19 | 0.2 | 0/8 |

| FR24H | FLGKGLVWV | 4047 | 29 | 2.3 | 1/4 | |

| FR25 | FR3 | AVYLQMNSL | 14 | 20 | 0.1 | 0/8 |

| FR25H | AVYLQMNSV | 512 | 26 | 2.4 | 1/4 | |

| FR26 | FR3 | TLYLQMDNL | 77 | 21 | 0.6 | 0/5 |

| FR26H | KLYLQMDNV | 878 | 22 | 1.3 | 2/4 | |

| FR27 | FR3 | SVIAADTAV | 6 | 19 | 0.1 | 0/2 |

| FR27H | KVIAADTAV | 243 | 24 | 0.9 | 1/2 | |

| FR28 | FR3 | NQFTLKLTSV | 60 | 17 | 0.5 | 0/2 |

| FR28H | NLFTLKLTSV | 2071 | 28 | 1 | 0/2 | |

| FR29 | FR3 | NQFSLKLSSV | 60 | 17 | 0.3 | 0/2 |

| FR29H | KLFSLKLSSV | 2071 | 28 | 0.8 | 0/2 | |

| FR30 | FR3 | TLYLQMNSL | 157 | 24 | 0.1 | 0/2 |

| FR30H | KLYLQMNSV | 1792 | 25 | 0.5 | 1/2 | |

| FR31 | FR3 | AVYYCARDLV | 10 | 16 | 0.7 | 0/2 |

| FR31H | KVYYCARDLV | 382 | 21 | 0.09 | 1/2 | |

| CDR16 | CDRI | IVSDNCMSWV | 537 | 17 | 0.5 | 1/5 |

| CDR16H | ILSDNCMSWV | 6132 | 23 | 1.8 | 1/4 | |

| CDR17 | CDRII | KGLEWISGYI | 6 | 17 | 0.6 | 0/2 |

| CDR17H | KLLEWISGYV | 6072 | 29 | 1.3 | 1/2 | |

| MAGE | aa 271 | FLWGPRALV | 2655 | 27 | 2.6 | 12/12 |

Shown are the name, position, sequence (single-letter abbreviations for amino acids) with heteroclitic changes (in boldface and underlined), calculated score of predicted half-life (Parker et al29 and Rammensee et al31) in arbitrary units, fluorescence index (FI) of binding to human HLA-A*0201, and number of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) lines generated from healthy donors that elicited specific killing of peptide-pulsed, CD40-activated B cells for all peptides tested.

FR indicates framework region; CDR, complementarity-determining region; and MAGE, melanoma antigen.

Selection of heteroclitic peptides

Eighteen Ig-derived peptides from patients with B-cell malignant diseases were chosen on the basis of low binding to HLA-A*0201 or low frequency of generation of CTL lines generated against APCs pulsed with these peptides.17 The native and heteroclitic versions of the peptides were synthesized. One native peptide (framework region [FR] 13) could not be synthesized because of its high hydrophobicity; therefore, 35 Ig V region–derived peptides were tested. Sixteen of the peptides were derived from the FRs, and 2 were from the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs). All peptides were screened with the computer prediction analysis for their binding affinity.

To generate the modified or heteroclitic peptides, single and double amino acid substitutions were made at the HLA A*0201 binding motif or anchor residues. Alterations were made to amino acids at position 1 or 2 (or both) and 9 or 10 (substitution with lysine at position 1, leucine at position 2, and valine at position 9 or 10), with the intention of not altering the T-cell–recognition region of the peptide. Heteroclitic peptides were selected for synthesis when the substitutions most markedly increased computer scores for predicted binding compared with the native peptides, with the intention of increasing binding affinity most efficiently (Table 1).

Evaluation of binding affinity of Ig-derived (native and heteroclitic) peptides to HLA-A*020

To determine whether predicted peptides could bind to HLA-A2, we used a cellular peptide-binding assay employing the transporter associated with antigen-processing–deficient cell line T2 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA). For this and subsequent analyses, a total of 17 peptides and 18 modified peptides (Table 1) were synthesized. T2 cells were pulsed with 50 μg/mL peptide and 5 μg/mL β-2 microglobulin (Sigma, St Louis, MO) for 18 hours at 37°C. HLA-A*0201 expression was then measured by using monoclonal antibody (mAb) BB7.2 (ATCC) followed by incubation with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated F(ab′)2goat antimouse Ig (Zymed, San Francisco, CA). Fluorescence index (FI) was calculated as the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of HLA-A*0201 on T2 cells as determined by fluorescence-activated cell-sorting (FACS) analysis, according to the following formula: FI = (MFI [T2 cells + peptide]/MFI [T2 cells without peptide]) −1.

Screening for peptide-specific HLA-restricted CTLs

For screening peptide-specific CTL responses, we used a previously established system.17,38 Briefly, purified HLA-A2–positive CD8+ T cells from healthy donors were primarily stimulated with irradiated monocyte-derived, peptide-pulsed dendritic cells and restimulated weekly with irradiated, peptide-pulsed, CD40-activated B cells.42 After 4 stimulations, more than 90% of cells in each culture were CD3+ lymphocytes, of which more than 90% were CD8+ and 0.6% to 5.4% were CD4+. Cultures were less than 0.6% CD14+ and 1.9% to 4.6% CD56+. The cytotoxic activity of CTL lines was assessed after 4 to 5 stimulations by using peptide-pulsed and unpulsed CD40-activated B cells or malignant B cells in chromium 51 (51Cr)–release assays. The concentration of peptide used for pulsing the CD-40 activated B cells resulted in maximal killing of the targets. When CLL cells were used as targets, the B-cell population was obtained by negative depletion using anti–T cell, natural killer cell, and monocyte mAbs and magnetic bead depletion. In each case, more than 95% of resulting cells coexpressed CD19 and CD5. Specific lysis was calculated as the percentage of specific 51Cr release by using the following formula: (E − S/T − S) × 100, where E is experimental 51Cr release, S is the spontaneous51Cr release, and T is the total 51Cr release by 2% Triton X-100. The purity of cell populations was determined by dual-color FACS using directly conjugated mAbs against CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, CD20, CD56, and CD14 (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Results for specific killing were assessed for each T-cell line generated and were compared with those observed with autologous T-cell lines generated against unpulsed APCs. MHC restriction of lytic activity was tested against HLA-A2–negative tumors or by blockade of HLA-A2 using mAb BB7.2 and the isotype control mAb B5.

Tetramer synthesis and staining

Purified HLA-A*0201 peptide monomeric complexes were obtained from ProImmune (Oxford, United Kingdom). To obtain tetramers, streptavidin-phycoerythrin (PE) conjugate (Sigma) was added at a 1:4 molar ratio. Tetramers were assembled for the native peptides FR16, FR17, and FR23, as well as their heteroclitic counterparts. CD8+ T-cell lines were generated as described above. T cells were stained with PE-labeled tetramer and CD8 FITC-labeled mAb (Dako) for 30 minutes on ice. After washing, stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL).

Results

Generation of native and modified Ig-derived peptides

We previously showed that CTLs can be generated against peptides derived from clonal Ig in B-cell malignancies in a peptide-specific and MHC-restricted way.17 A limitation of this approach was the low binding affinity of most peptides from the clonal Ig sequences: it was not always possible to generate CTLs, especially against these low-affinity peptides. We therefore examined whether alteration to the MHC-binding sequences would increase the binding affinity of altered Ig-derived peptides and whether CTLs could then be generated against these altered peptides that would also have specificity for the native peptide. Therefore, we assessed Ig-derived peptides from 70 patients with B-cell malignant diseases in whom the Ig region had been sequenced and who expressed HLA-A*0201. The peptides chosen for further examination had previously been found by us to have low binding to HLA-A*0201 and a low frequency of generation of CTL lines generated against APCs pulsed with these peptides.17 A surprising finding of this study was that the CDR3 region contained few peptides with predicted binding potential and it was difficult to find peptides from this region for which the native peptide would likely be presented by the tumor cell as a target for T cells generated against the heteroclitic peptides.

Seventeen native peptides (one native FR-derived peptide could not be synthesized because of its hydrophobicity) and 18 heteroclitic peptides were included in this study. Their sequences and positions in the Ig region are shown in Table 1. Sixteen of these sequences were derived from the FRs. As was previously reported,17 many of these FR-derived peptides are shared by multiple patients and are therefore not unique tumor-associated antigens. Two peptides were derived from the CDRs. One FR-derived peptide (FR16) was from the κ light chain; all other peptides were from the Ig heavy-chain V region. Eleven peptides were nonamer and 7 were decamer oligopeptides.

The predicted score for binding of the native peptides was examined by using 2 separate computer algorithms (Table 1). Alterations to the MHC-binding peptides were examined in these algorithms to increase predicted binding to HLA-A*0201. These modifications consisted of substitutions of lysine at position 1, leucine at position 2, or valine at position 9. The sequences of both the native and heteroclitic peptides are shown in Table 1 with the amino acid substitutions in boldface and underlined. The predicted binding for the heteroclitic peptides was increased in all cases except FR9, for which the predicted binding increased in one algorithm but not the other.

Binding affinity of native and modified Ig-derived peptides

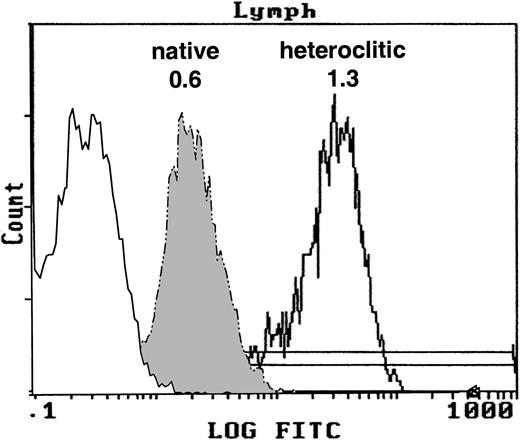

We examined whether the heteroclitic peptides had increased affinity to HLA-A*0201 by using the T2 binding assay. The FI for the native and heteroclitic peptides was calculated. Representative results demonstrating the binding of the native and heteroclitic FR17 peptides are shown in Figure 1, and results obtained for all peptides tested are shown in Table 1. We observed a significant increase in binding of the heteroclitic peptides compared with the native peptide (P < .0001 on paired ttesting). The FI did not increase in only one case (FR9), and the predicted binding affinity was also not increased in one of the computer algorithms for this peptide.

T2 binding assay.

Expression of MHC class I molecule on T2 cells without peptide after addition of the native peptide FR17 (FI = 0.6) and enhanced expression after addition of the heteroclitic peptide FR17H (FI = 1.3).

T2 binding assay.

Expression of MHC class I molecule on T2 cells without peptide after addition of the native peptide FR17 (FI = 0.6) and enhanced expression after addition of the heteroclitic peptide FR17H (FI = 1.3).

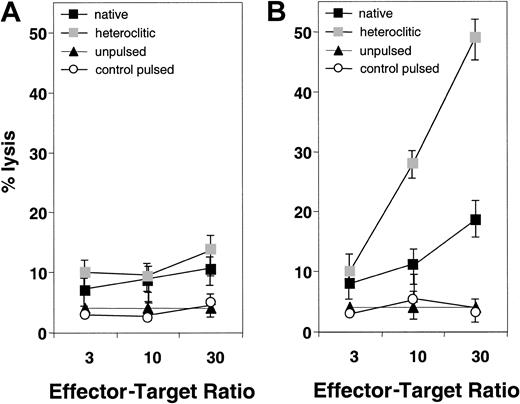

Peptide-specific CTL reactivity against targets pulsed with heteroclitic peptides

We next attempted to generate T-cell lines against the native and heteroclitic peptides and determine whether the resulting T cells were capable of inducing specific lysis of autologous peptide-pulsed APCs. Representative results are shown in Figure2 for T-cell lines generated against native and heteroclitic peptide CDR16. Figure 2A shows results for the T-cell line generated against the native CDR16 peptide, which induced only weak killing of target cells pulsed with either native or heteroclitic peptide. Figure 2B shows results obtained by using a T-cell line generated against the heteroclitic peptide CDR16H. For 8 of the peptide pairs for which no cytotoxicity was observed with any of the T-cell lines generated against the native peptide, T-cell lines could be generated against the heteroclitic peptide (Table 1). In other cases, we were able to generate T-cell lines more readily and show more specific lysis with the lines generated against the heteroclitic peptide. Table 1 shows results obtained for all donors tested and the number of donors in whom CTLs with specificity for the peptide-pulsed, CD40-activated B cells (measured by chromium-release assays) could be generated. CTLs could not be generated against either the native or heteroclitic peptide in only 2 cases (FR28 and FR29).

Specificity of killing of CD40-activated B cells pulsed with native and heteroclitic peptides.

(A) Killing by T-cell lines generated against native peptide CDR16 of unpulsed CD40-activated B cells and CD40-activated B cells pulsed with heteroclitic peptide, native peptide, or control peptide (FR9) at the effector-to-target ratios shown. (B) Killing by T-cell lines generated against heteroclitic peptide CDR16H of unpulsed CD40-activated B cells and CD40-activated B cells pulsed with heteroclitic peptide, native peptide, or control peptide (FR9) at effector-to-target ratios shown. Results are mean ± SD values from experiments done in triplicate with samples from a single donor and are representative of results from experiments done with samples from 5 different donors.

Specificity of killing of CD40-activated B cells pulsed with native and heteroclitic peptides.

(A) Killing by T-cell lines generated against native peptide CDR16 of unpulsed CD40-activated B cells and CD40-activated B cells pulsed with heteroclitic peptide, native peptide, or control peptide (FR9) at the effector-to-target ratios shown. (B) Killing by T-cell lines generated against heteroclitic peptide CDR16H of unpulsed CD40-activated B cells and CD40-activated B cells pulsed with heteroclitic peptide, native peptide, or control peptide (FR9) at effector-to-target ratios shown. Results are mean ± SD values from experiments done in triplicate with samples from a single donor and are representative of results from experiments done with samples from 5 different donors.

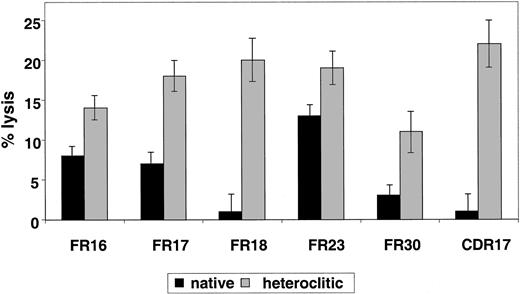

Results pertaining to specific lysis of CD40-actived B cells pulsed with the native compared with the heteroclitic peptide by autologous T-cell lines generated against each of the remaining peptides are shown in Figure 3. The findings represent killing of the peptide-pulsed, CD40-activated B cells subtracted from that of the unpulsed CD40-activated B cells. In all cases, killing of the unpulsed CD40-activated B cells was 5% or less. Although there was a correlation between predicted binding, FI, and ability to induce CTL responses, this was not present in all cases (Table 1). Thus, the algorithms are still incomplete and it is necessary to use a functional assay, such as the one described here, to confirm that changes result in improved binding and generation of CTL responses.

Killing of CD40-activated B cells pulsed with native and heteroclitic peptides.

Cytotoxicity of T-cell lines generated against native and heteroclitic peptides, with killing of CD40-activated autologous B cells pulsed with the peptide at an effector-to-target ratio of 30:1. Results are mean ± SD values from experiments done in triplicate with samples from up to 8 different donors.

Killing of CD40-activated B cells pulsed with native and heteroclitic peptides.

Cytotoxicity of T-cell lines generated against native and heteroclitic peptides, with killing of CD40-activated autologous B cells pulsed with the peptide at an effector-to-target ratio of 30:1. Results are mean ± SD values from experiments done in triplicate with samples from up to 8 different donors.

Heteroclitic CTLs lyse target cells bearing the native peptide

Our most important goal was to determine whether T-cell lines generated against the heteroclitic peptide were also capable of killing cells expressing the native peptide that would be expressed by the tumor cell. To examine this question, we generated T-cell lines against the native and heteroclitic peptides and examined killing by these T-cell lines of CD40-activated B cells pulsed with the original native peptide. In 7 of the 14 matched-pair analyses done, T-cell lines generated against the heteroclitic peptide were also able to kill the CD40-activated B cells pulsed with the native peptide. In all cases, killing with the T-cell line generated against the heteroclitic peptide was greater than that by T-cell lines generated against the native peptide itself (Figure 2B and Figure 4). It was not surprising that, in some cases, the T-cell lines were not able to kill the CD40-activated B cells pulsed with the native peptide, since the binding affinity of the native peptide for the MHC class I molecule was low. Under these circumstances, it is also likely that the native peptide would not be processed and presented by the tumor cell with sufficient efficiency to present a target of an immune response.

T cells generated against heteroclitic peptide kill targets pulsed with native peptide.

Killing with T-cell lines generated against native or heteroclitic peptide of CD40-activated autologous B cells pulsed with native peptide at an effector-to-target ratio of 30:1. Results are mean ± SD values from experiments done in triplicate with samples from 3 different donors.

T cells generated against heteroclitic peptide kill targets pulsed with native peptide.

Killing with T-cell lines generated against native or heteroclitic peptide of CD40-activated autologous B cells pulsed with native peptide at an effector-to-target ratio of 30:1. Results are mean ± SD values from experiments done in triplicate with samples from 3 different donors.

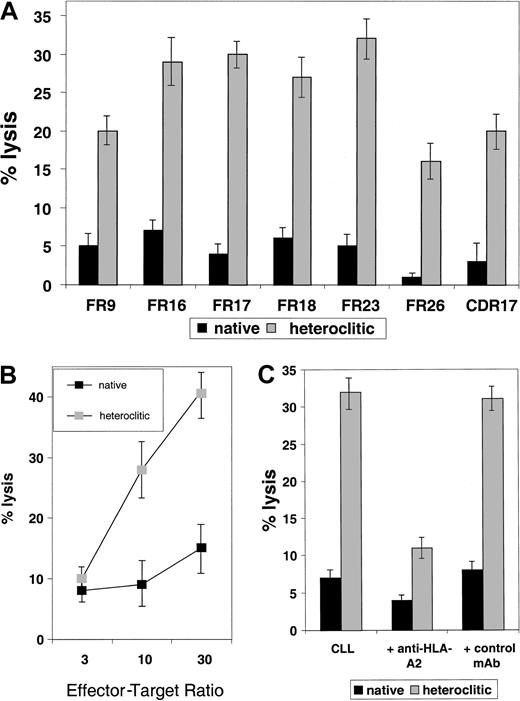

Peptide-specific CTLs can kill CLL cells

To examine whether T-cell lines generated against the heteroclitic peptide could kill not only CD40-activated normal B cells pulsed with the native peptide but also the tumor cell from which the Ig sequence was obtained, cytotoxicity assays were done by using the primary tumor cells as targets. All tumor samples tested as targets of cytotoxicity were obtained from patients with CLL who had not previously been treated. In each case, non-B cells were depleted by negative depletion, and more than 95% of the resulting cells were CLL cells as indicated by coexpression of CD19 and CD5. In 7 cases (Figure5A), we found that T-cell lines generated against the heteroclitic peptide were more efficient at killing CLL cells than were T-cell lines generated against the native peptide. This finding shows that low-affinity peptides that are ineffective in generating an immune response can still be targets of a T-cell–mediated immune response generated against an altered peptide. Efficient killing required a high ratio of effector-to-target (Figure5B).

Killing of CLL cells by T-cell lines generated against native and heteroclitic peptides.

(A) Killing of CLL cells with a T-cell line generated against native or heteroclitic peptide with rearranged Ig gene containing the sequence for the FR9, FR16, FR17, FR18, FR23, FR26, and CDR17 peptides. Results shown are at an effector-to-target ratio of 30:1 and are the mean ± SD values from experiments done in triplicate with samples from 3 different donors. (B) Killing of CLL cells by a T-cell line generated from autologous T cells against FR17 native and heteroclitic peptides at the effector-to-target ratios shown. (C) Killing of CLL cells occurs in an MHC-restricted manner and is inhibited by addition of anti–HLA-A2 mAb at a concentration of 5 μg/mL.

Killing of CLL cells by T-cell lines generated against native and heteroclitic peptides.

(A) Killing of CLL cells with a T-cell line generated against native or heteroclitic peptide with rearranged Ig gene containing the sequence for the FR9, FR16, FR17, FR18, FR23, FR26, and CDR17 peptides. Results shown are at an effector-to-target ratio of 30:1 and are the mean ± SD values from experiments done in triplicate with samples from 3 different donors. (B) Killing of CLL cells by a T-cell line generated from autologous T cells against FR17 native and heteroclitic peptides at the effector-to-target ratios shown. (C) Killing of CLL cells occurs in an MHC-restricted manner and is inhibited by addition of anti–HLA-A2 mAb at a concentration of 5 μg/mL.

All results reported here are for killing of nonactivated CLL cells. However, we have also observed more efficient killing of CD40-activated CLL cells compared with nonactivated tumor cells.17In addition, we found increased killing of tumor cells when they were pulsed with exogenous peptide,17 suggesting that mechanisms that lead to increased antigen presentation might make these tumor cells more susceptible to CTL-mediated killing. Killing occurred in an MHC class I–specific manner and was inhibited by addition of anti–HLA-2 mAb (Figure 5C).

Enumeration of antigen-specific T cells by using HLA class I tetramers against native and heteroclitic peptides

After 4 stimulations of the T-cell lines with peptide-pulsed autologous APCs, more than 90% of the cells were CD8+ T cells, for each of the peptides studied. Staining with the HLA-A*0201 peptide tetramers for the native peptides FR16, FR17, and FR23, as well as their heteroclitic counterparts, was done for T-cell lines generated from healthy HLA-A*0201 donors against the native peptide and heteroclitic counterparts. Results are shown in Table2. We observed no peptide-specific T cells in any of the samples from healthy donors. After 4 to 5 stimulations using APCs pulsed with the native or heteroclitic peptides, specific T cells were observed in each of the resulting T-cell lines. In each case, T cells generated against the heteroclitic peptide were also detected by the tetramer for the native peptide and vice versa, demonstrating that the T-cell–recognition region of the peptide was likely not altered by the amino acid substitutions at the anchor residues. In one donor, we observed the expected higher frequency of specific cells after stimulation with the heteroclitic peptide (17.3%) compared with that observed in the donor after stimulation with the native peptide (1.46%). However, surprisingly, overall we observed no difference in the frequency of T cells observed after stimulation for the heteroclitic peptide compared with the native peptide (P = .3).

Tetramer staining of T-cell lines generated against native and heteroclitic peptides

| Tetramer . | Healthy donors . | T cells generated against native peptide . | T cells generated against heteroclitic peptide . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative control | 0.04 | 0.30 | 0.06 |

| FR16 | 0.02 | 1.57 | 1.38 |

| FR16H | 0.06 | 2.34 | 9.96 |

| Negative control | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.03 |

| FR17 | 0.04 | 2.07 | 2.61 |

| FR17H | 0.03 | 3.52 | 2.79 |

| Negative control | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| FR23 | 0.02 | 1.19 | 2.46 |

| FR23H | 0.02 | 1.95 | 2.13 |

| Tetramer . | Healthy donors . | T cells generated against native peptide . | T cells generated against heteroclitic peptide . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative control | 0.04 | 0.30 | 0.06 |

| FR16 | 0.02 | 1.57 | 1.38 |

| FR16H | 0.06 | 2.34 | 9.96 |

| Negative control | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.03 |

| FR17 | 0.04 | 2.07 | 2.61 |

| FR17H | 0.03 | 3.52 | 2.79 |

| Negative control | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| FR23 | 0.02 | 1.19 | 2.46 |

| FR23H | 0.02 | 1.95 | 2.13 |

Shown is enumeration of peptide-specific T cells by tetramer staining of T cells from healthy donors and of T-cell lines generated against the framework region (FR) 16, FR17, and FR23 native and heteroclitic peptides. Shown is the frequency of CD8+ T cells generated against FR16, FR17, and FR23 and their heteroclitic counterparts that stain with specific tetramer, the heteroclitic tetramer, and a negative control tetramer.

Discussion

The idiotype is the best-characterized tumor antigen expressed in B-cell malignant diseases. It can function as a target for T-cell–mediated1-4 and humoral immune responses.4-10 However, in many cases, these responses do not lead to a sustained clinical response. Furthermore, technical limitations in synthesizing the full Ig protein and the need to produce an individual molecule for each patient have hampered more widespread use of this approach. In addition, only a small number of Ig-derived peptides appear to have the ability to induce a specific CD8+ CTL response.17 In an attempt to overcome this limitation and increase the pool of immunogenic Ig-derived peptides, we generated peptides with conservative modifications of the HLA-binding residues of the peptides. We examined this approach in 18 peptides with weak binding to HLA-A*0201. The resulting heteroclitic peptides showed improved binding to MHC class I molecules and improved killing of peptide-pulsed target cells. T-cell lines generated against the heteroclitic peptide killed not only target cells pulsed with that peptide but also showed increased killing of target cells pulsed with the native peptide. Most important, these T-cell lines also killed primary tumor cells that presumably express only the native peptide.

Sixteen of the 18 peptides we examined were derived from the FR. We reasoned that there was no advantage in raising T cells against heteroclitic peptides if the native peptide had extremely low binding affinities and would therefore be unlikely to be presented by the tumor cell itself. The CDR3 contained very few peptides with predicted binding potential. It is possible that there might be a selection bias against rearrangements that lead to expression of peptides from the CDRs with high binding affinity, since the B cells would be depleted by T-cell responses against such determinants. A possible advantage of FR-derived peptides is that they are not limited to a single patient. We previously found that some peptides examined are expressed in up to 20% of patients with B-cell malignant diseases.17 Indeed, 34 of the 70 patients examined shared at least one peptide. A major concern about use of this approach is some normal B cells will also express targeted FR-derived peptides. Clinical trials with the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab in which virtually all B cells are eliminated have not revealed severe side effects caused by B-cell deficiency.43 44 However, there are clearly differences between induction of an active immune response with a vaccination approach and loss of B cells after passive administration of an antibody. An ongoing active immune response against the FR could lead to loss of all normal B cells expressing that peptide sequence and this could theoretically result in a defect in the B-cell repertoire. Ongoing studies are addressing this issue in murine models in vivo.

We observed a difference between killing of malignant B cells and normal B cells. This could represent differential killing of malignant compared with normal B cells by changes in processing of Ig-derived peptides. However, we believe that it more likely indicates that normal B cells that share the FR peptides would be killed; however, because most normal B cells do not express that particular FR peptide, the observed killing did not increase above background levels. In addition, although the FR peptides are shared by malignant and normal B cells, we did not observe detectable T cells with specificity for these peptides in samples from any healthy donor on MHC class I–peptide tetramer staining. The mechanisms by which normal activated B cells, which are effective APCs, do not elicit such responses are not known. Certainly, T cells capable of reacting against these peptides exist in the repertoire and can be expanded in vitro by using the system described here. In vivo, tolerance might be induced against these FRs, and it is possible that the in vitro system we used activates cross-reacting T cells. Indeed, the relatively low specific lysis observed in vitro might be due to the fact that tolerance must be overcome.

Heteroclitic peptides were shown to improve induction of CTL responses against MAGEs in both murine models40 and trials in humans.41 Introduction of conservative modifications at particular amino acid positions in the peptide resulted in an increase in low HLA-A*0201-binding affinity and enhanced recruitment of T-cell repertoire against peptides with nondominant anchor residues.28,31,45 46 In the current study, use of heteroclitic peptides enhanced binding and cytotoxicity. The finding that the frequency of specific T cells was not enhanced against heteroclitic compared with native peptides was therefore surprising. The observation that CTLs could be enumerated after immunization with even weak Ig-derived peptides is encouraging, however, but suggests that the frequency of T cells generated might not be as important as the avidity of the TCR of the resulting T cells for the target peptide and the ability of the tumor cell to present the target peptide.

Our experiments show that by changing amino acids of anchor residues, HLA-peptide binding can be improved, as predicted by computer algorithms and confirmed by T2 binding. CTLs raised against heteroclitic peptides can kill target cells bearing the native peptide, and lysis of primary CLL cells can be improved by generating T cells against heteroclitic peptides. We therefore conclude that MHC class I–restricted heteroclitic peptides can enlarge the pool of immunogenic peptides in B-cell malignant diseases and enhance the immunogenicity of these peptides. Whether these findings have implications for immunotherapy approaches in these diseases—for use of heteroclitic peptides as vaccines or incorporation of changes in the structure of the whole Ig constructs to enhance MHC class I binding of Ig-derived peptides and enhance cytotoxicity—will be clarified by the results of ongoing in vivo murine experiments to determine whether such increased cytotoxicity also depletes the normal B-cell repertoire.

Supported by grants CA78378 and CA81534 from the National Cancer Institute to J.G.G. and by the Grace B. Kerr Foundation. M.W. and A.M.K. were supported by grants from the Deutsche Krebshilfe and Dr Mildred Scheel Stiftung.

S.H. and M.W. contributed equally to this study.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

John G. Gribben, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 44 Binney St, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: john_gribben@dfci.harvard.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal