Abstract

Angiogenesis is required for the progression of tumors from a benign to a malignant phenotype and for metastasis. Malignant tumor cells secrete factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which bind to their cognate receptors on endothelial cells to induce angiogenesis. Here it is shown that several tumor types express VEGF receptors (VEGFRs) and that inhibition of VEGF (VEGF antisense oligonucleotide AS-3) or VEGFRs (neutralizing antibodies) inhibited the proliferation of these cell lines in vitro. Furthermore, this effect was abrogated by exogenous VEGF. Thus, VEGF is an autocrine growth factor for tumor cell lines that express VEGFRs. A modified form of VEGF AS-3 (AS-3m), in which flanking 4 nucleotides were substituted with 2-O-methylnucleosides (mixed backbone oligonucleotides), retained specificity and was active when given orally or systemically in vitro and in murine tumor models. In VEGFR-2–expressing tumors, VEGF inhibition may have dual functions: direct inhibition of tumor cell growth and inhibition of angiogenesis.

Introduction

Angiogenesis is the process whereby new blood vessels sprout in response to local stimuli. These primarily consist of the release of angiogenic factors, activation of metalloproteases to break down extracellular matrix, and subsequent remodeling. The switch to the angiogenic phenotype is crucial in both tumor progression and metastasis.1 The key factor involved in nearly all human tumors is vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).2,3VEGF is preeminent in blood vessel formation. Loss of only one allele in knockout mice causes embryonic death.4,5 Likewise, the VEGF receptors (VEGFRs) were also demonstrated to be essential for blood vessel formation by gene knockout in mice.6,7Heightened expression of VEGFRs in the endothelial cells of tumor vasculature further attests to the significance of VEGF in tumor angiogenesis.8 9

VEGF binds with high affinity to its cognate receptors flt-1/VEGFR-1, flk-1/KDR/VEGFR-2, and neuropilin-1.10-12 VEGFR-2 is responsible for mitogenic signaling,13 while VEGFR-1 participates in cell migration.14-16 VEGF is regulated by several factors, including hypoxia, cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1, activation of certain oncogenes (Ras, Raf, Src), and loss-of-function mutations of p53 and the von Hippel–Lindau genes.17-22 Elevated tumor or serum VEGF levels are in many cases predictive of poor survival.23-34 The prognostic value of VEGF has been proposed to be related to enhanced angiogenesis in the tumor.

Ectopic expression of VEGFR-2 in nonendothelial cell lines does not lead to a VEGF-mediated mitogenic response,35suggesting that only the endothelial cells are configured to carry mitogenic VEGF signal to the nucleus. We hypothesized that during neoplastic transformation nonendothelial cells may acquire aberrant expression of VEGFR-2 and the downstream signaling to VEGF. Furthermore, we propose that autocrine growth factor activity in tumor cells may contribute to metastatic potential and poor outcome.

Our previous study demonstrated that VEGF is an autocrine growth factor for Kaposi sarcoma,36 in which tumor cells express an endothelial cell phenotype.37 VEGF inhibitors including VEGF antisense oligonucleotide AS-3 have been shown to synergize with other agents such as epidermal growth factor antibody against colon carcinoma.38 In the current study, we show that inhibition of VEGF expression (using VEGF AS-3) or blocking binding of VEGF to VEGFR (using VEGFR-1 or VEGFR-2 neutralizing antibodies) results in growth inhibition of tumor cell lines that express VEGFRs. Furthermore, the specificity of VEGF AS-3 was confirmed by the demonstration that VEGF AS-3 is taken up by the cells, that it inhibits VEGF production, that exogenous VEGF blocks the inhibitory effect, and that point mutations in AS-3 substantially reduce its activity. Thus, VEGF autocrine growth activity is acquired by certain tumor cell lines defined by the expression of VEGFRs.

We also studied a mixed backbone modification to the VEGF AS-3 in which 4 nucleotides were substituted with 2′-O-methylribonucleosides at both 3′ and 5′ ends.39 This modification (AS-3m) retained specificity to VEGF and was shown to be active when administered orally and parenterally in various murine tumor models. Furthermore, VEGF AS-3m had an additive antitumor effect when combined with a chemotherapeutic agent. In addition to being antiangiogenic, VEGF AS-3m may also directly inhibit tumor growth in tumors that express the VEGFRs.

Materials and methods

Oligonucleotides

VEGF-specific oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN), referred to here as AS-3 and complementary to VEGF messenger RNA (mRNA) (261 to 281),40 and 2 mutants of AS-3 were synthesized with or without 5′ fluorescein tag (Operon Technologies, Alameda, CA) as shown in Table 1. AS-3m, the mixed backbone oligonucleotide (MBO) derivative of AS-3, 5′-UGGCTTGAAGATGTACTCGAU-3′ and a control 21-mer mixed backbone ODN, referred to here as “scrambled,” 5′-UCGCACCCATCTCTCTCCUUC-3′ were synthesized, purified, and analyzed as previously described.41 Four nucleotides at the 5′ end and 4 nucleotides at the 3′ end are 2′-O-methylribonucleosides; the remaining are deoxynucleosides. For both MBOs, all internucleotide linkages are phosphothioate. The purity of the oligonucleotides was shown to be more than 90% by capillary gel electrophoresis and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, with the remainder being n-1 and n-2 products. The integrity of the internucleotide linkage was confirmed by 31P nuclear magnetic resonance.

Sequences of VEGF antisense ODN and mutants

| Oligonucleotide . | Sequence . |

|---|---|

| AS-3 | 5′-TGG CTT GAA GAT GTA CTC GAT-3′ |

| AS-3 mut1 | 5′-TGG CTT GAA GAT GTA CTG CAT-3′ |

| AS-3 mut2 | 5′-TGG CTT GAA CAT GTA CTC GAT-3′ |

| Oligonucleotide . | Sequence . |

|---|---|

| AS-3 | 5′-TGG CTT GAA GAT GTA CTC GAT-3′ |

| AS-3 mut1 | 5′-TGG CTT GAA GAT GTA CTG CAT-3′ |

| AS-3 mut2 | 5′-TGG CTT GAA CAT GTA CTC GAT-3′ |

Mutated bases are shown in bold.

Cell lines and reagents

The cell lines T1, HuT 78, A375, LNCaP, U937, and HL-60 were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Other cell lines were obtained from colleagues at the University of Southern California; M2142 was from P. Brooks, 526 from J. Weber, Hey and Hoc-7 from L. Dubeau, and Panc-3 from D. Parekh. KS Y-1 has been described previously.37 VEGFR-1 (C-17) and VEGFR-2 (C-1158) neutralizing polyclonal antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). VEGFR-2 polyclonal antibody, IL-8 monoclonal antibody (clone 6217.111), and recombinant human VEGF were purchased from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Preparation of cDNA and RT-PCR

Total RNA was prepared from 1 × 105 cells. Complementary DNAs (cDNAs) were synthesized by reverse transcription (RT) using a random hexamer primer in a total volume of 20 μL (Superscript II, Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). A total of 5 μL of the cDNA reaction was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as previously described.36 Each PCR cycle consisted of denaturation at 94°C for 1 minute, primer annealing at 60°C for 2 minutes, and extension at 72°C for 3 minutes. The samples were amplified for 30 cycles. Amplified product was visualized on 1.5% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide. The integrity and quantity of cDNA was confirmed for all samples by amplification of β-actin. Primers used to amplify specific gene products are listed in Table2. For semiquantitative PCR, samples were amplified for 41 cycles. Aliquots (5 μL) were removed after every 4 cycles starting at cycle 25.

Gene-specific primers for RT-PCR

| Gene . | Orientation . | Sequence . |

|---|---|---|

| VEGF | Forward | 5′-CGA AGT GGT GAA GTT CAT GGA TG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TTC TGT ATC AGT CTT TCC TGG TGA G-3′ | |

| VEGFR-1 | Forward | 5′-CAA GTG GCC AGA GGC ATG GAG TT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GAT GTA GTC TTT ACC ATC CTG TTG-3′ | |

| VEGFR-2 | Forward | 5′-GAG GGC CTC TCA TGG TGA TTG T-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TGC CAG CAG TCC AGC ATG GTC TG-3′ | |

| β-actin | Forward | 5′-GTG GGG CGC CCC AGG CAC CA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CTC CTT AAT GTC ACG CAC GAT TTC-3′ |

| Gene . | Orientation . | Sequence . |

|---|---|---|

| VEGF | Forward | 5′-CGA AGT GGT GAA GTT CAT GGA TG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TTC TGT ATC AGT CTT TCC TGG TGA G-3′ | |

| VEGFR-1 | Forward | 5′-CAA GTG GCC AGA GGC ATG GAG TT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GAT GTA GTC TTT ACC ATC CTG TTG-3′ | |

| VEGFR-2 | Forward | 5′-GAG GGC CTC TCA TGG TGA TTG T-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TGC CAG CAG TCC AGC ATG GTC TG-3′ | |

| β-actin | Forward | 5′-GTG GGG CGC CCC AGG CAC CA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CTC CTT AAT GTC ACG CAC GAT TTC-3′ |

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was used to analyze the expression of cell surface molecules. All cell lines (KS Y-1, M21, Hey, T1, U937) were seeded at a density of 1 × 106 per T75 flask in appropriate culture media. Adherent cells (KS Y-1, M21, Hey, T1) were harvested on the following day using a rubber policeman. Cells grown in suspension (U937, HL-60, A6876, P3HR1) and adherent cells were transferred to 12 × 15 mm round-bottomed centrifuge tubes. Viable cell counts were determined by trypan blue dye exclusion. Cells were incubated with VEGFR antibodies (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) followed by 1 hour of incubation with antirabbit fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugate (Sigma, St Louis, MO). The cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) after each incubation. Cell pellets were suspended in 1 mL PBS and analyzed with a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). The data are presented as mean fluorescence intensity ratios (mean fluorescence intensity with antibody of interest/mean fluorescence intensity with control isotype-specific rabbit immunoglobulin G [IgG]). Negative controls were cells incubated with antirabbit FITC, with no prior exposure to receptor-specific antibodies.

Fluorescence studies

The 5′ fluorescein-tagged AS-ODNs listed in Table 1 were synthesized (Operon Technologies). KS Y-1, M21, and Hey cells were seeded onto chamber slides (Nunc, Rochester, NY) at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in serum-containing medium and allowed to attach overnight. The medium was replaced with serum-free medium, and the cells were exposed to 1 or 10 μM fluorescein-tagged AS-3, AS-3 mut1, or AS-3 mut2 for 4 hours. Cationic lipids or permeabilizing agents were not used to enhance oligonucleotide uptake. At the conclusion of the 4-hour incubation, the cells were washed 5 times with PBS to remove unbound ODNs. Nuclei were stained with propidium iodide using standard techniques. Localization of the fluorescein and propidium iodide staining was determined by confocal microscopy using a Zeiss 510 LSM microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

Cell proliferation assay

Cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 per well in 24-well gelatin-coated plates on day 0 in appropriate growth media containing 2% fetal calf serum (FCS), except for KS Y-1, where 1% FCS was used. On the following day, the media were changed and cells were treated with various concentrations (1-10 μM) of oligonucleotides or VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2 neutralizing antibodies (10, 100, and 1000 ng/mL). Medium was changed, and treatment was repeated on day 3. On day 5, viability was assessed using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) at a final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL. Cells were incubated for 2 hours, medium was aspirated, and the cells were dissolved in acidic isopropanol (90% isopropanol, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 40 mM HCl). Optical density was read in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader at 490 nm using the isopropanol as blank (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Determination of VEGF and IL-8 protein levels

Cells were cultured in RPMI containing 2% FCS for these experiments. Cells were treated with various concentrations of the oligonucleotides at hour 0 and 16. The supernatants were collected at 24 hours, centrifuged to remove all cell debris, and stored at −70°C until analysis using ELISA kits (R & D Systems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Levels of VEGF detected were corrected for cell numbers. Tumor tissues from the in vivo experiments on tumor growth were lysed, and the levels of VEGF protein were determined using both the human VEGF ELISA kit and a mouse VEGF ELISA kit (R & D Systems). Levels of VEGF detected were corrected for total protein.

Western blotting

M21 cells (5 × 105) were treated with 10 μM of either AS-3m or scrambled ODN using lipofectamine (1 μg/mL) in RPMI supplemented with 1% FCS for 8 hours. Media were replaced with RPMI supplemented with 5% FCS, and cells were harvested and lysed after 36 hours (lysis buffer: 10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 10 000g for 10 minutes. Total protein was determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). Samples (20 μg protein) were fractionated on a 4% to 20% Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gel and transferred to nylon membrane (Bio-Rad) by electroblotting. Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk prior to incubation with monoclonal antibody to VEGF or IL-8 (1 μg/mL) at 4°C for 16 hours. The membranes were developed using the Immun-Star Goat antimouse IgG kit (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

In vivo studies

Human tumor cell lines KS Y-1, M21, and Hey (2 × 106 cells) were injected subcutaneously in the lower back of 5-week-old male BALB/C nu/nu athymic mice. In the first protocol, treatment consisted of daily oral administration of AS-3m or scrambled MBO or diluent (PBS) begun the day following tumor cell implantation and continued for 2 weeks. Dosing was 10 mg/kg in 100 μL PBS by gavage. In the second protocol, designed to test tumor regression, the cells were implanted and the xenograft was allowed to establish for 5 days before treatment was initiated. Treatment consisted of daily intraperitoneal injection of AS-3m (1, 5, or 10 mg/kg in a total volume of 100 μL) or diluent. Taxol (1.25 or 2.5 mg/kg) treatment, where indicated, was by intraperitoneal injection on days 5 and 12. Tumor growth in mice was measured 3 times a week. Mice were killed at the conclusion of the study. Tumors were collected and analyzed for VEGF levels. All mice were maintained in accordance with the University of Southern California institutional guidelines governing the care of laboratory mice.

Orthotopic implantation of tumor cells

Cultured PC-3P cells (60%-80% confluent) were harvested for injection. Mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine, and a lower midline incision was made. Tumor cells (1 × 105/10 μL) in Hank's balanced salt solution were implanted in the dorsal prostate lobes using a dissecting microscope. The cells were injected through a 30-gauge needle using a syringe with a calibrated push button–controlled dispensing system. Formation of a small bulla at the injection site indicated a successful injection. The prostate gland was returned to its natural location, and the abdominal incision was closed. Mice were treated with either saline or the study drug beginning on day 10. Six mice were included in each group. The treated group received VEGF AS-3m at a dose of 10 mg/kg intraperitoneally daily for 2 weeks. Mice were killed on day 24 after the tumor implantation. Prostate and tumors were excised under a dissecting microscope. The tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Tissue sections were stained with either hematoxylin and eosin or were processed for immunocytochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed tissue sections were deparaffinized and incubated with 10% goat serum at −70°C for 10 minutes and incubated with the primary rabbit antibodies against either VEGFR-1 or VEGFR-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) (1:100) at 40°C overnight. Isotype-specific rabbit IgG was used as control. The immunoreactivity for these receptors was revealed using an avidin-biotin kit from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). Peroxidase activity was revealed by the diaminobenzidine (Sigma) cytochemical reaction. The slides were then counterstained with 0.12% methylene blue or hematoxylin and eosin. Detection of apoptosis by the TUNEL assay was carried out as described previously.43

Results

Expression of VEGF and VEGFRs in human tumor cell lines

VEGF production was assessed in a variety of human tumor cell lines. Human melanoma (M21), human ovarian carcinoma (Hey and Hoc-7), and human prostate carcinoma (LNCaP) all secrete high levels of VEGF into the culture medium (Table 3). This is in contrast to a human T-cell leukemia cell line (HuT 78) and human fibroblasts (T1), which do not have detectable VEGF. We also determined VEGF mRNA levels by RT-PCR in these cell lines and others, including Panc-3, representative of pancreatic carcinoma, and A375 and 526, both representative of melanoma. HuT 78 T-cell leukemia, HL-60 erythroid leukemia cell line, and T1 fibroblast cell lines did not express VEGF (Table 3, Figure 1A).

Expression of VEGF and its receptors in tumor cell lines

| Cell line . | Type . | VEGF (pg/106cells)3-150 . | VEGFR-2 (Flk-1) . | VEGFR-1 (Flt-1) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KS Y-1 | Kaposi sarcoma | + (625) | + | + |

| M21 | Melanoma | + (487) | + | + |

| A375 | Melanoma | + | + | + |

| 526 | Melanoma | + | + | + |

| Hey | Ovarian carcinoma | + (419) | + | + |

| Hoc-7 | Ovarian carcinoma | + (550) | + | + |

| Panc-3 | Pancreatic carcinoma | + | + | + |

| LNCaP | Prostate carcinoma | + (719) | + | − |

| U937 | Promonocytoid | + (1476) | − | + |

| HL-60 | Erythroid leukemia | − | − | − |

| HuT 78 | T-cell leukemia | − | − | − |

| T1 | Fibroblast | − | − | − |

| Cell line . | Type . | VEGF (pg/106cells)3-150 . | VEGFR-2 (Flk-1) . | VEGFR-1 (Flt-1) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KS Y-1 | Kaposi sarcoma | + (625) | + | + |

| M21 | Melanoma | + (487) | + | + |

| A375 | Melanoma | + | + | + |

| 526 | Melanoma | + | + | + |

| Hey | Ovarian carcinoma | + (419) | + | + |

| Hoc-7 | Ovarian carcinoma | + (550) | + | + |

| Panc-3 | Pancreatic carcinoma | + | + | + |

| LNCaP | Prostate carcinoma | + (719) | + | − |

| U937 | Promonocytoid | + (1476) | − | + |

| HL-60 | Erythroid leukemia | − | − | − |

| HuT 78 | T-cell leukemia | − | − | − |

| T1 | Fibroblast | − | − | − |

Cells were cultured for 48 hours. VEGF levels in the supernatants were measured by ELISA.

Expression of VEGFR-2/KDR and VEGFR-1/flt-1 in various tumor cell lines.

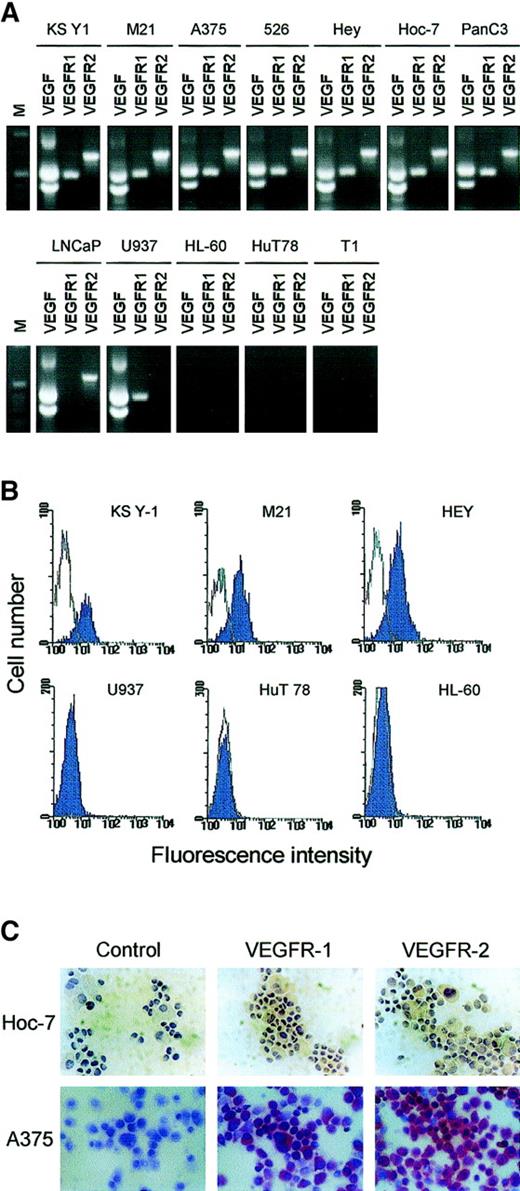

(A) RT-PCR of VEGF, VEGFR-1, and VEGFR-2 in a panel of human tumor cell lines. The cDNA was prepared and amplified using gene-specific primers as described in “Materials and methods.” Amplified products of the predicted sizes (VEGF, 535 and 403 base pairs; VEGFR-1, 498 base pairs; VEGFR-2, 709 base pairs) are observed in all of the cells in the upper row. In the lower row are cells that failed to show expression of one or all of the components tested. (B) KS Y-1, M21, Hey, U937, HL-60, and HuT 78 cells were incubated with FITC-labeled VEGFR-2 antibody as described in “Materials and methods” and analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells on the upper row expressed VEGFR-1; those on the lower row did not express the receptor. (C) Immunocytochemical staining of Hoc-7 ovarian carcinoma cells and A375 melanoma cells for VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2. For Hoc-7, brown color is signal; for A375, crimson color is signal. Specificity of immunostaining was demonstrated in both cases by lack of signal with isotype-specific controls (control).

Expression of VEGFR-2/KDR and VEGFR-1/flt-1 in various tumor cell lines.

(A) RT-PCR of VEGF, VEGFR-1, and VEGFR-2 in a panel of human tumor cell lines. The cDNA was prepared and amplified using gene-specific primers as described in “Materials and methods.” Amplified products of the predicted sizes (VEGF, 535 and 403 base pairs; VEGFR-1, 498 base pairs; VEGFR-2, 709 base pairs) are observed in all of the cells in the upper row. In the lower row are cells that failed to show expression of one or all of the components tested. (B) KS Y-1, M21, Hey, U937, HL-60, and HuT 78 cells were incubated with FITC-labeled VEGFR-2 antibody as described in “Materials and methods” and analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells on the upper row expressed VEGFR-1; those on the lower row did not express the receptor. (C) Immunocytochemical staining of Hoc-7 ovarian carcinoma cells and A375 melanoma cells for VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2. For Hoc-7, brown color is signal; for A375, crimson color is signal. Specificity of immunostaining was demonstrated in both cases by lack of signal with isotype-specific controls (control).

We then examined the expression of VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2. A number of human tumor cell lines derived from melanoma, ovarian carcinoma, and pancreatic carcinoma showed VEGFR expression by several different methods, including RT-PCR, immunocytochemistry, and flow cytometry (Table 3, Figure 1). Flow cytometry and RT-PCR also showed that HL-60 and HuT 78 did not express VEGFR-1 or VEGFR-2 (Figure 1A,B). U937, a monocytoid cell line, expressed high levels of VEGFR-1 (Table 3, Figure1A) but not VEGFR-2. The coexpression of VEGF and its receptors in some of these tumor cell lines raised the possibility of autocrine growth factor activity. This activity could be tested by blocking expression of the ligand, VEGF.

VEGF AS-3 specifically blocks VEGF expression in a sequence-dependent manner

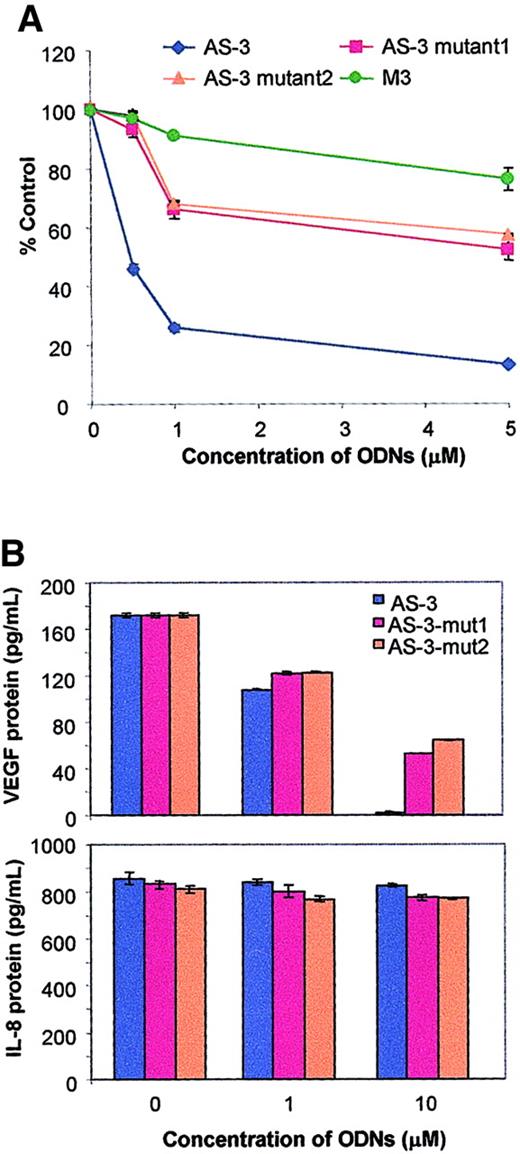

We have previously demonstrated the existence of an autocrine growth regulatory pathway for VEGF in KS cells using VEGF phosphorothioate antisense ODNs.36 AS-3 and 2 mutant AS-3 sequences with changes of either 1 or 2 nucleotides (Table 1) (all phosphothioate-modified) were tested for their effect on the viability of cell lines that show VEGF-dependent autocrine growth factor activity. A dose-dependent loss of viability was observed with AS-3, while both mutants were significantly less active (Figure2A). AS-3 mut2, which has a single base change, resulted in a 60% loss in efficacy at a concentration of 2.5 μM AS-3. Results were similar for AS-3 mut1.

VEGF antisense specifically inhibits VEGF.

(A) Effect of AS-3 and mutant AS-ODNs on the viability of KS Y-1 cells in vitro. Cells were seeded at 1 × 104 cells per well in 24-well plates and treated with the ODNs as indicated on days 1 and 3. Cell viability was performed on day 5 by MTT assay. Results represent the mean ± SE of quadruplicate samples. We also tested a previously described VEGF AS ODN, M3.64 (B) Effect of AS-3 and mutant AS-ODNs on the production of VEGF and IL-8. Cells were cultured in media supplemented with 2% FCS for these experiments. Cells were treated with various concentrations of the oligonucleotides at hours 0 and 16. The supernatants were collected at hour 24 and assayed for VEGF and IL-8 using ELISA kits. Results are presented as median of replicate experiments ± SE.

VEGF antisense specifically inhibits VEGF.

(A) Effect of AS-3 and mutant AS-ODNs on the viability of KS Y-1 cells in vitro. Cells were seeded at 1 × 104 cells per well in 24-well plates and treated with the ODNs as indicated on days 1 and 3. Cell viability was performed on day 5 by MTT assay. Results represent the mean ± SE of quadruplicate samples. We also tested a previously described VEGF AS ODN, M3.64 (B) Effect of AS-3 and mutant AS-ODNs on the production of VEGF and IL-8. Cells were cultured in media supplemented with 2% FCS for these experiments. Cells were treated with various concentrations of the oligonucleotides at hours 0 and 16. The supernatants were collected at hour 24 and assayed for VEGF and IL-8 using ELISA kits. Results are presented as median of replicate experiments ± SE.

To confirm the sequence dependence of the ODN activity, the effect of AS-3 and the 2 mutant sequences on VEGF production over 8 and 24 hours was determined. VEGF protein production was nearly completely inhibited using 10 μM AS-3, while the effects of either of the 2 mutants were substantially less (Figure 2B). This shows that inhibition of VEGF is sequence-dependent. In short-term experiments, a higher dose of the ODN was required for complete inhibition of VEGF. To confirm that the decrease in VEGF production seen with AS-3 treatment was specific, the same supernatants were studied for the production of IL-8. IL-8 levels in the supernatants were not affected by the parent compound, AS-3, or either of the 2 mutants (Figure 2B). Thus, the activity of AS-3 is highly specific for inhibition of VEGF and is sequence-dependent.

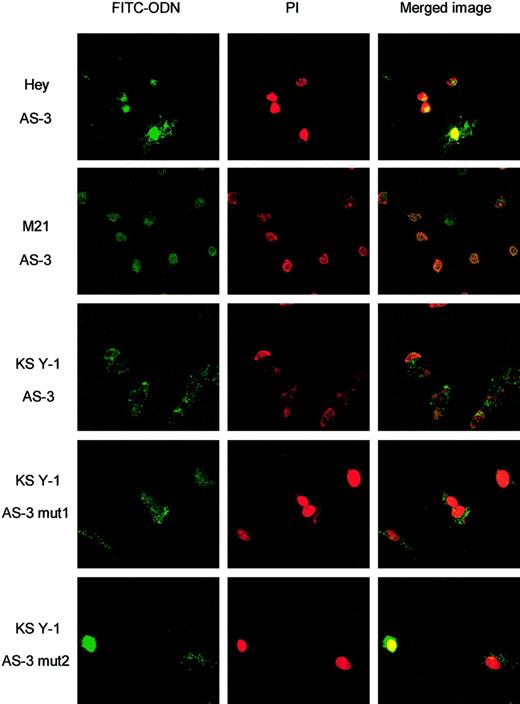

To determine that the reduced activity of the mutants was not related to the failure of cellular uptake, fluorescein-labeled ODNs were used. FITC signal is detectable in the cells of all samples treated with the lowest concentration of the ODN tested (1 μM). Overlay of the FITC image and propidium iodide, which stains DNA, indicates that the ODNs appear to be localized predominantly to the nucleus (Figure3). The cellular uptake and nuclear localization was not affected by mutation of 1 or 2 nucleotides.

Fluorescein-tagged VEGF ODNs are taken up by various tumor cell lines in vitro.

Shown are the FITC images in the first column of treatments as indicated and the propidium iodide (PI) nuclear stain in the second column. Overlay images of ODN fluorescein signal exposed to AS-3, AS-3 mut1, and AS-3 mut2 (1 μM) are in the third column and show colocalization of the FITC and PI staining, indicating that the ODNs have entered the nuclei. Control was no treatment (no fluorescent AS-ODN; not shown).

Fluorescein-tagged VEGF ODNs are taken up by various tumor cell lines in vitro.

Shown are the FITC images in the first column of treatments as indicated and the propidium iodide (PI) nuclear stain in the second column. Overlay images of ODN fluorescein signal exposed to AS-3, AS-3 mut1, and AS-3 mut2 (1 μM) are in the third column and show colocalization of the FITC and PI staining, indicating that the ODNs have entered the nuclei. Control was no treatment (no fluorescent AS-ODN; not shown).

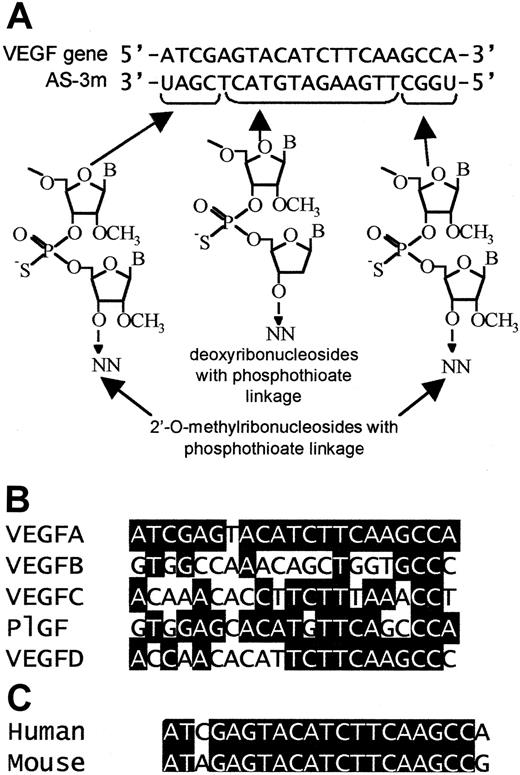

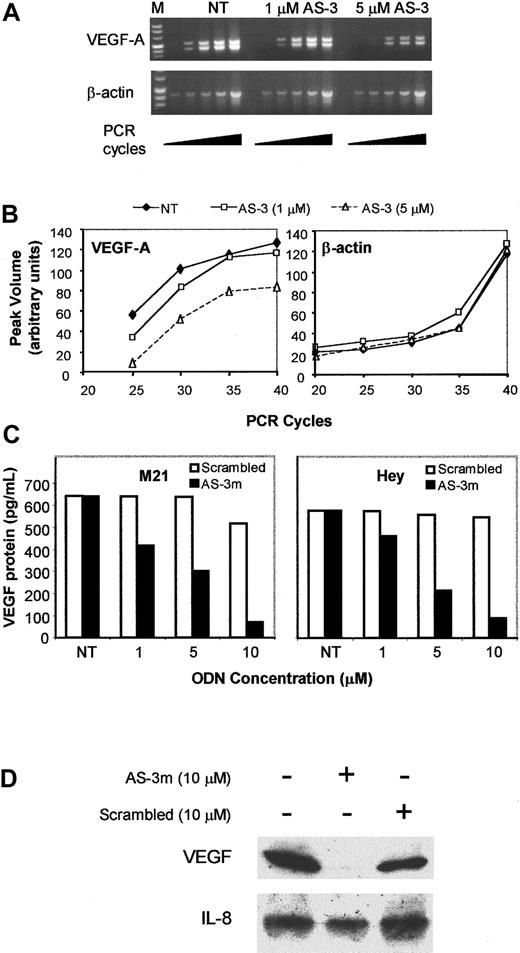

An MBO corresponding to the previously described AS-3 sequence (Figure4A) was also tested for specificity of activity in KS Y-1 cells. The sequence of AS-3m is complementary to VEGF mRNA and contains a number of mismatches for the other VEGF family genes (Figure 4B). Treatment of KS Y-1 cells with AS-3m led to a dose-dependent inhibition of VEGF mRNA compared with untreated control (Figure 5A,B). The unrelated β-actin message was not affected, indicating that the effect is specific. Because AS-3m significantly inhibited VEGF message, the effect on protein production in vitro was determined. Incubation of both M21 melanoma and Hey ovarian carcinoma cell lines with AS-3m (Figure 5B) or KS Y-1 with AS-3 (Figure 2B) resulted in a dose-dependent drop in the levels of VEGF protein in the culture supernatants. No significant effects were seen using the scrambled MBO. In addition, Western blots showed a specific and total down-regulation of intracellular VEGF in response to AS-3m treatment, with no effect on IL-8 in M21 and KS Y-1 (Figure 5D and data not shown). This is in agreement with the specific inhibition of secreted VEGF in KS Y-1 where IL-8 was not affected (Figure 2B). The slight inhibition of intracellular VEGF seen with the scrambled control ODN in M21 correlates with the decrease in secreted protein seen at this concentration (Figure 5B). This demonstrated that the mixed backbone derivative of AS-3 also inhibits VEGF expression and protein production.

VEGF antisense MBOs.

(A) Schematic representation of the mixed backbone formulation oligonucleotides. Shown are the human VEGF gene sequence and complementary AS-3 sequences. The chemical structures of the modified bases are shown below. (B) Comparison of the corresponding areas of the VEGF family members: The highlighted bases indicate identity between VEGF-B, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, or PlGF and VEGF-A. Homology between the genes is not high in this region. (C) Comparison of the sequences in the human and mouse VEGF genes that are complementary to AS-3. The mouse sequence shown here is nucleotides 288 to 308 of the sequence reported by Claffey et al.60 Identity is indicated by highlighted blocks.

VEGF antisense MBOs.

(A) Schematic representation of the mixed backbone formulation oligonucleotides. Shown are the human VEGF gene sequence and complementary AS-3 sequences. The chemical structures of the modified bases are shown below. (B) Comparison of the corresponding areas of the VEGF family members: The highlighted bases indicate identity between VEGF-B, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, or PlGF and VEGF-A. Homology between the genes is not high in this region. (C) Comparison of the sequences in the human and mouse VEGF genes that are complementary to AS-3. The mouse sequence shown here is nucleotides 288 to 308 of the sequence reported by Claffey et al.60 Identity is indicated by highlighted blocks.

Mixed backbone antisense AS-3m inhibits VEGF mRNA and protein production.

(A) Total RNA was isolated from KS Y-1 cells treated with various concentrations of AS-3m as indicated (NT indicates not treated). Total RNA was reverse-transcribed to generate cDNA. Aliquots of the reaction mixture were removed at 5-cycle intervals to provide semiquantitative analysis for amplification of VEGF relative to β-actin as described in “Materials and methods.” Integrity of RNA in the samples was verified by β-actin amplification. (B) Band intensities shown in panel A were quantitated using the Quantity One program (Bio-Rad). Shown are estimated PCR products as a function of cycle; the units are arbitrary for each RT-PCR. Bands were undetectable below 25 cycles for VEGF. (C) Effect of AS-3m on VEGF protein production in 2 tumorigenic cell lines: Human melanoma cell line M21 (left panel) and human ovarian carcinoma cell line Hey (right panel) were treated with VEGF antisense AS-3m and the scrambled MBO at concentrations ranging from 1 to 10 μM. Supernatants were collected at 24 hours, and VEGF protein was quantitated by ELISA. The results represent the means of duplicate determinations. (D) Western blot of M21 cell lysates. Cells were treated for 8 hours with the ODNs indicated and harvested 36 hours later. Crude protein extracts were prepared from the cells, and 20 μg each was fractionated by 4% to 20% Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteins were electrotransferred to nylon membranes and immunoblotted with antibodies to VEGF or IL-8 (1 μg/mL) as described in “Materials and methods.”

Mixed backbone antisense AS-3m inhibits VEGF mRNA and protein production.

(A) Total RNA was isolated from KS Y-1 cells treated with various concentrations of AS-3m as indicated (NT indicates not treated). Total RNA was reverse-transcribed to generate cDNA. Aliquots of the reaction mixture were removed at 5-cycle intervals to provide semiquantitative analysis for amplification of VEGF relative to β-actin as described in “Materials and methods.” Integrity of RNA in the samples was verified by β-actin amplification. (B) Band intensities shown in panel A were quantitated using the Quantity One program (Bio-Rad). Shown are estimated PCR products as a function of cycle; the units are arbitrary for each RT-PCR. Bands were undetectable below 25 cycles for VEGF. (C) Effect of AS-3m on VEGF protein production in 2 tumorigenic cell lines: Human melanoma cell line M21 (left panel) and human ovarian carcinoma cell line Hey (right panel) were treated with VEGF antisense AS-3m and the scrambled MBO at concentrations ranging from 1 to 10 μM. Supernatants were collected at 24 hours, and VEGF protein was quantitated by ELISA. The results represent the means of duplicate determinations. (D) Western blot of M21 cell lysates. Cells were treated for 8 hours with the ODNs indicated and harvested 36 hours later. Crude protein extracts were prepared from the cells, and 20 μg each was fractionated by 4% to 20% Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteins were electrotransferred to nylon membranes and immunoblotted with antibodies to VEGF or IL-8 (1 μg/mL) as described in “Materials and methods.”

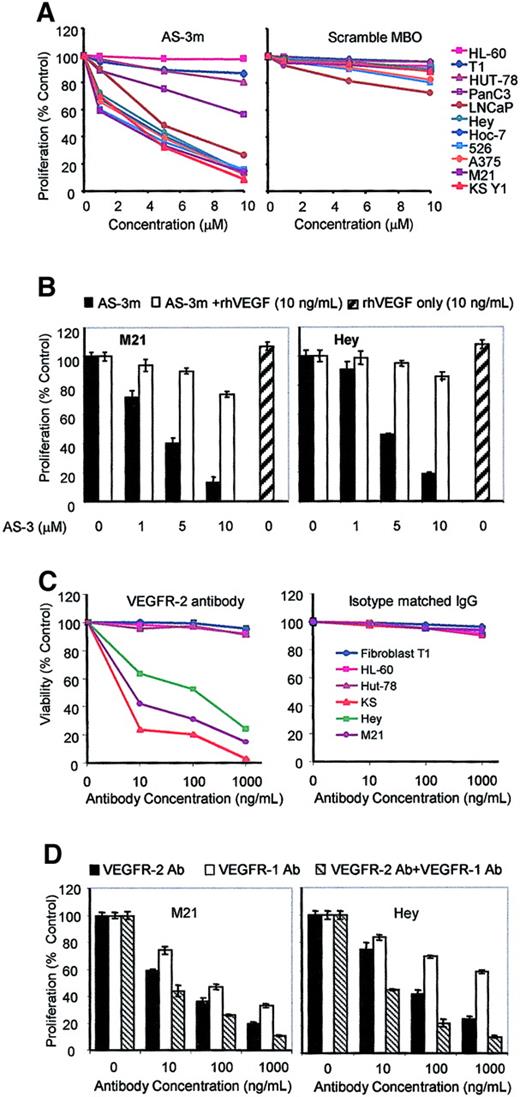

VEGF AS-3 and VEGFR neutralizing antibodies directly inhibit tumor cell proliferation in vitro

It has been suggested that VEGFRs function only in the context of endothelial cells, because ectopic expression of VEGFRs using expression vectors failed to establish VEGF-mediated signaling in certain nonendothelial lineage cell types.35 In the course of neoplastic transformation, cells may acquire the ability to not only express VEGF but also to acquire VEGFRs and signaling pathways specific to VEGF. If this were the case, cell lines that express both VEGF and the cognate receptors could be examined for the presence of a VEGF autocrine growth regulatory loop. Several tumor cell lines from diverse tumor types express both VEGF and VEGFRs (Table 3, Figure 1). There is a range of response to VEGF inhibition. Notably, the tumor cell lines that showed the most inhibition of cell viability were those that expressed both VEGF and VEGFRs. Melanoma and ovarian carcinoma cell lines showed the most response and were similar to KS cell line (KS Y-1). In sharp contrast, the cell lines that failed to show response were erythroleukemia (HL-60), T-cell leukemia HuT 78, and fibroblast (T1) cell lines that lack VEGF and VEGFR expression. Results were similar for VEGF AS-3 or VEGF AS-3m (Figure6A, left panel). Scrambled MBO-derived ODN had no effect except for minimal toxicity at higher dose levels in selected cell lines (Figure 6A, right panel). The role of VEGF in cell viability was further confirmed by the addition of recombinant hVEGF, which nearly completely abrogated the effect of AS-3m in M21 (Figure6B, left panel) and Hey cells (Figure 6B, right panel). At this dose, exogenous recombinant human (rh)VEGF itself has no effect on viability.

Mixed backbone antisense AS-3m or VEGFR antibody inhibits tumor cell proliferation in vitro.

Cells were seeded at 1 × 104 cells per well in 24 plates and treated with AS-3m (1, 5, 10 μM) on days 1 and 3 (A). Cell viability was performed on day 5 by MTT assay. Results represent the mean ± SD of quadruplicate samples. Specificity of the AS-3m ODN is shown by the lack of significant cytotoxicity in any cell line of the scrambled ODN (right panel). (B) The rhVEGF abrogates the effect of VEGF antisense. Cell lines M21 and Hey were seeded as above and were treated with 1, 5, and 10 μM AS-3m alone or with rhVEGF (10 ng/mL) on day 1 and day 2. Cell viability was measured after 72 hours. AS-3m inhibition of cell proliferation in both cell lines (black columns) could be reversed by the presence of VEGF (white columns), which did not have any appreciable effect on the growth of cells (hatched columns). The data represent the mean ± SD of 2 experiments performed in quadruplicate. (C) Cell viability studies were repeated with VEGFR-2 neutralizing antibody or unrelated (perforin polyclonal) antibody. VEGFR-2 inhibited the viability of the cell lines shown to express VEGFRs. No significant effect was seen on cell lines not expressing VEGFRs or with unrelated antibody. (D) VEGFR-1 antibody reduces proliferation in cell lines that express VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2. Cultures of M21 or Hey were treated as in panel C with VEGFR-1 antibody, VEGFR-2 antibody, or both. VEGFR-1 reduced cell proliferation but to a lesser extent than VEGFR-2. Both antibodies result in a more pronounced decrease than with VEGFR-2 alone.

Mixed backbone antisense AS-3m or VEGFR antibody inhibits tumor cell proliferation in vitro.

Cells were seeded at 1 × 104 cells per well in 24 plates and treated with AS-3m (1, 5, 10 μM) on days 1 and 3 (A). Cell viability was performed on day 5 by MTT assay. Results represent the mean ± SD of quadruplicate samples. Specificity of the AS-3m ODN is shown by the lack of significant cytotoxicity in any cell line of the scrambled ODN (right panel). (B) The rhVEGF abrogates the effect of VEGF antisense. Cell lines M21 and Hey were seeded as above and were treated with 1, 5, and 10 μM AS-3m alone or with rhVEGF (10 ng/mL) on day 1 and day 2. Cell viability was measured after 72 hours. AS-3m inhibition of cell proliferation in both cell lines (black columns) could be reversed by the presence of VEGF (white columns), which did not have any appreciable effect on the growth of cells (hatched columns). The data represent the mean ± SD of 2 experiments performed in quadruplicate. (C) Cell viability studies were repeated with VEGFR-2 neutralizing antibody or unrelated (perforin polyclonal) antibody. VEGFR-2 inhibited the viability of the cell lines shown to express VEGFRs. No significant effect was seen on cell lines not expressing VEGFRs or with unrelated antibody. (D) VEGFR-1 antibody reduces proliferation in cell lines that express VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2. Cultures of M21 or Hey were treated as in panel C with VEGFR-1 antibody, VEGFR-2 antibody, or both. VEGFR-1 reduced cell proliferation but to a lesser extent than VEGFR-2. Both antibodies result in a more pronounced decrease than with VEGFR-2 alone.

These results were confirmed using VEGFR-2 neutralizing monoclonal antibody. Dose-dependent inhibition of cell growth was observed in cell lines that express VEGFRs, the same lines that showed growth inhibition with AS-3m. Cell lines that do not express VEGFRs did not show toxicity (Figure 6C, left panel). Unrelated polyclonal antibody (to perforin) had no toxicity on any cell type (Figure 6C, right panel). We also wished to determine whether blocking VEGFR-1 in the same manner would inhibit cell growth. VEGFR-1 by itself does not initiate mitogenic signaling; instead it potentiates VEGFR-2 signaling by forming heterodimers with it that have higher VEGF binding affinity. VEGFR-1 antibody does inhibit cell proliferation (Figure 6D), although not as strongly as the VEGFR-2 antibody. The differences, however, may be related to the activity of the antibody or less efficient competition of VEGF-VEGFR interaction. In combination the VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 antibodies were more potent inhibitors of tumor cell proliferation than either alone. These results are of clinical significance because we and others have shown that a variety of tumor cells of nonendothelial origin express VEGF and VEGFR-1/VEGFR-2.44

Inhibition of tumor growth in vivo

AS-3m was tested in murine xenograft models of human ovarian carcinoma and melanoma. Treatment of mice bearing Hey ovarian carcinoma xenografts (Figure 7A) with 10 mg/kg AS-3m resulted in more than 90% tumor inhibition (Figure 7A, left panel). To exclude immune stimulatory effects from AS-3m antitumor activity, severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) beige mice bearing Hey ovarian carcinoma xenografts were treated with 10 mg/kg AS-3m or control (PBS). These mice lack B cells and T cells and have inactive natural killer (NK) cells and macrophages. AS-3m retained antitumor activity in the Hey ovarian tumor xenograft model in the absence of either an innate or adaptive immune system. Similarly, AS-3 was active against human melanoma M21 xenografts in athymic mice. Figure 7B (left panel) shows that a dose range of 1, 5, and 10 mg/kg resulted in M21 melanoma tumor growth inhibition of 20%, 68%, and more than 80%, respectively. In addition, an additive effect was observed when VEGF AS-3m was combined with low-dose Taxol in M21 tumor xenografts (Figure 7B, right panel), illustrating that the combined treatment regimens were more potent than either agent used alone. It is apparent that the effects of Taxol and AS-3m at the doses used here are additive.

Effect on tumor growth of mixed backbone VEGF antisense oligonucleotides in vivo.

Tumor xenografts were initiated by subcutaneous inoculation of cell lines in the lower back of BALB/C nu/nu athymic mice as described in “Materials and methods.” AS-3m was administered intraperitoneally daily for the study duration. (A) Effect of AS-3m on ovarian (Hey) tumors. Tumor growth curve in BALB/C athymic mice, which lack mature T-cells (left panel), and SCID beige mice in which T cells and B cells are absent and NK cells and macrophages are nonfunctional. In the absence of any appreciable immune function, AS-3m has antitumor activity. (B) Effect of combined treatment with AS-3m and chemotherapy (Taxol) on 5-day established M21 tumor xenografts. AS-3m or PBS was injected intraperitoneally daily beginning day 5. Taxol (2.5 mg/kg) was given intraperitoneally on days 5 and 12. The left panel shows dose response to AS-3m alone. The right panel shows results of combined treatments. Final tumor weights are shown to the right of the growth curves in each graph. Data represent the mean ± SD of 6 mice in each group.

Effect on tumor growth of mixed backbone VEGF antisense oligonucleotides in vivo.

Tumor xenografts were initiated by subcutaneous inoculation of cell lines in the lower back of BALB/C nu/nu athymic mice as described in “Materials and methods.” AS-3m was administered intraperitoneally daily for the study duration. (A) Effect of AS-3m on ovarian (Hey) tumors. Tumor growth curve in BALB/C athymic mice, which lack mature T-cells (left panel), and SCID beige mice in which T cells and B cells are absent and NK cells and macrophages are nonfunctional. In the absence of any appreciable immune function, AS-3m has antitumor activity. (B) Effect of combined treatment with AS-3m and chemotherapy (Taxol) on 5-day established M21 tumor xenografts. AS-3m or PBS was injected intraperitoneally daily beginning day 5. Taxol (2.5 mg/kg) was given intraperitoneally on days 5 and 12. The left panel shows dose response to AS-3m alone. The right panel shows results of combined treatments. Final tumor weights are shown to the right of the growth curves in each graph. Data represent the mean ± SD of 6 mice in each group.

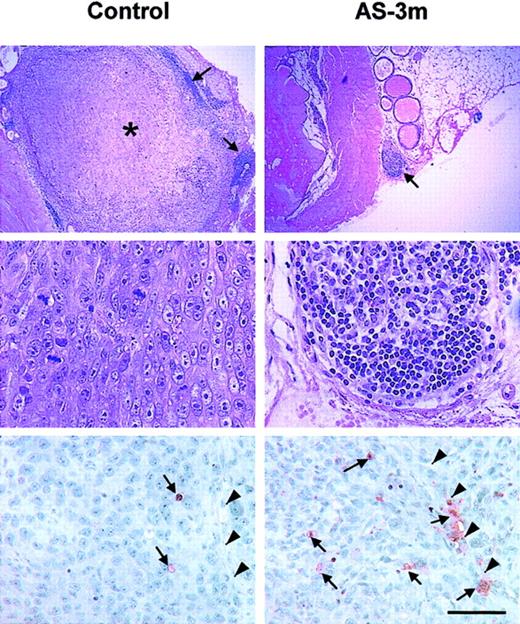

VEGF AS-3 was also active in an orthotopic prostate cancer model. Expression of VEGF increases with advancing prostate carcinoma and even more so when the tumor becomes hormone-independent. Palliative therapy is the only treatment for nonresectable tumors. Prostate gland stroma plays a critical role in tissue remodeling and tumor regulation. Direct tumor implantation of the mouse prostate gland with the human prostate tumor cell line (PC3) was performed to determine if inhibition of VEGF would have an antitumor effect. Treatment was delayed to 10 days postimplantation, and the treatment consisted of AS-3m daily at a dose of 10 mg/kg. Mice were killed 3 weeks after tumor implantation, and the prostate gland was harvested for analysis. All control mice (n = 6) developed tumor at the site of injection in the prostate (Figure8, top left and center left shows a representative tumor at low- and high-power magnification). Small tumors were seen in only 2 of the 6 treated mice (Figure 8, top right and center right; low- and high-power images). Tumors from treated mice showed infiltration with leukocytes (Figure 8, top right arrow and densely staining cells in the center right panel) in contrast to the circumferential localization of these cells in the control mice (Figure 8, top left, arrows). These data underscore the need for further understanding of the role VEGF plays in the mechanism of immune cell migration and maturation.

Tumors of treated mice show reduced tumor size and increased apoptosis.

The top 4 panels are photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of PC-3 orthotopic tumors. Top and center left panels show that control mice treated with the diluent alone (PBS) reveal a large tumor (indicated by asterisk) encircled by immune cells (arrows) noted by dense nuclear stain (at lower power) and a high mitotic rate in the tumor at higher power. Top and center right panels show that VEGF AS-3–treated mice reveal a small tumor nodule within the prostate gland (arrow), showing infiltration with immune cells at higher power. Data representative of TUNEL staining for apoptosis in mice bearing human ovarian tumor are shown in the lower two panels. Mice treated with AS-3m show increased apoptosis in the cells lining the vascular structures and the tumor tissue (right panel). Mice receiving the diluent show substantially fewer apoptotic cells (left panel). Apoptotic cells stain red and are indicated by arrows; arrowheads indicate a tumor vessel. The scale bar represents 70 μm.

Tumors of treated mice show reduced tumor size and increased apoptosis.

The top 4 panels are photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of PC-3 orthotopic tumors. Top and center left panels show that control mice treated with the diluent alone (PBS) reveal a large tumor (indicated by asterisk) encircled by immune cells (arrows) noted by dense nuclear stain (at lower power) and a high mitotic rate in the tumor at higher power. Top and center right panels show that VEGF AS-3–treated mice reveal a small tumor nodule within the prostate gland (arrow), showing infiltration with immune cells at higher power. Data representative of TUNEL staining for apoptosis in mice bearing human ovarian tumor are shown in the lower two panels. Mice treated with AS-3m show increased apoptosis in the cells lining the vascular structures and the tumor tissue (right panel). Mice receiving the diluent show substantially fewer apoptotic cells (left panel). Apoptotic cells stain red and are indicated by arrows; arrowheads indicate a tumor vessel. The scale bar represents 70 μm.

MBOs are orally bioavailable.39 AS-3m administered orally inhibited KS Y-1 tumor xenograft growth (data not shown). Detailed studies of the efficiency of absorption and kinetics are underway.

The ovarian tumor xenografts for which growth curves were shown in Figure 7A were also examined for apoptotic cells by TUNEL assay. Tumors from control mice showed the occasional apoptotic cells (Figure 8, arrow, lower left panel) that were not adjacent to the vessel (Figure8, arrowheads). In contrast, apoptosis in the tumors of AS-3m–treated mice was more extensive; both perivascular cells and cells distant from vessels were involved (Figure 8, arrows, lower right panel; vessel indicated by arrowheads). Apoptosis of both tumor cells and endothelial cells is observed, consistent with the proposed dual mode of action of AS-3m in VEGFR-2+ tumor cells.

Effect of AS-3m on VEGF levels in vivo

Human (Hey) tumor xenografts were harvested 24 hours after the last dose of therapy, and tumor lysates were prepared. VEGF levels were quantitated and adjusted for total protein. Both human (tumor-derived) and mouse (host-derived) VEGF was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner by AS-3m. In a representative experiment, an approximately 60% reduction in the levels of both human and mouse VEGF was observed after a daily dose of 10 mg/kg (Table 4). The nucleotide sequence of VEGF AS-3 has a stretch of 17 nucleotides that are homologous to the mouse VEGF coding region (Figure 4C), which explains the targeting of mouse VEGF.

Serum levels of human and mouse VEGF in antisense-treated tumor-bearing mice

| Treatment group . | VEGF, mean pg/mg protein ± SEM . | |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse . | Human . | |

| Control (diluent only) | 76.14 ± 17.81 | 198.29 ± 29.88 |

| 1 mg/kg AS-3m | 47.11 ± 3.47 | 175.15 ± 33.54 |

| 5 mg/kg AS-3m | 34.68 ± 4.27 | 94.71 ± 19.574-150 |

| 10 mg/kg AS-3m | 31.15 ± 4.054-150 | 81.20 ± 15.504-150 |

| Treatment group . | VEGF, mean pg/mg protein ± SEM . | |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse . | Human . | |

| Control (diluent only) | 76.14 ± 17.81 | 198.29 ± 29.88 |

| 1 mg/kg AS-3m | 47.11 ± 3.47 | 175.15 ± 33.54 |

| 5 mg/kg AS-3m | 34.68 ± 4.27 | 94.71 ± 19.574-150 |

| 10 mg/kg AS-3m | 31.15 ± 4.054-150 | 81.20 ± 15.504-150 |

P < .05 compared with controls.

Discussion

VEGF plays a pivotal role in vasculogenesis and angiogenesis.45 A number of observations have spurred extensive investigation of VEGF inhibitors as possible therapies for cancer. The endothelial cell mitogen VEGF is overexpressed in tumor cells; VEGFRs are elevated in the tumor vasculature; and elevated VEGF levels are associated with tumor metastasis and lower survival.8,46,47 Inhibitors in development include monoclonal antibody to VEGF and inhibitors of VEGFR activation following ligand binding.48-50

The current report shows that a number of tumor cell lines produce VEGF and its cognate receptors. These results indicate a loss of regulatory function because prolonged VEGF exposure leads to down-regulation of the VEGFRs in normal endothelial cells.16 We further demonstrate that the receptors are functional in these tumor cell lines. The presence of VEGF autocrine growth factor activity was demonstrated in 4 different human tumor types, including melanoma, ovarian carcinoma, pancreatic carcinoma, and Kaposi sarcoma. These cells all express VEGF and the mitogenic receptor VEGFR-2 and show impaired viability in response to VEGF ablation by either VEGF AS-ODN or neutralizing VEGFR antibodies. The inhibition of cell viability was restored by exogenous VEGF. Expression of VEGFRs on tumor cells has been described previously,44 and mitogenic response to exogenous VEGF has been documented in pancreatic carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, and melanoma.51-53 Recently the presence of a VEGF autocrine growth loop in malignant mesothelioma has also been demonstrated.54 The presence of autocrine growth pathways in some tumors implies that VEGF antisense therapy is acting on 2 levels: antiangiogenic effects on the tumor vasculature and antineoplastic effects on the tumor cell population. VEGFR-2 expression in the tumor cells may thus predict for better response to VEGF ablation.

VEGF levels in malignant pleural effusions associated with a variety of tumors are elevated compared with sera of the patients or nonmalignant effusions.55-57 It has been suggested that VEGF is critical to this pathology. Evidence in support of this comes from a preclinical model in which VEGFR inhibition reduced the formation of pleural effusions.58 We suggest that AS-3m is a candidate for development as therapy for malignancies such as ovarian carcinoma and malignant mesothelioma, in which the formation of malignant pleural effusions is common.

AS-3, described here and previously,36 is an effective inhibitor of VEGF expression. In addition, AS-3 reduced the viability of 6 tumor cell lines, with an inhibitory concentration of 50% of 2.5 to 3 μM. AS-3 activity is specific, shown by a drop in VEGF protein secretion in vitro, with no effect on IL-8. In addition, VEGF mRNA was down-regulated in vitro on exposure to AS-3. AS-3 activity is sequence-dependent because a change of either 1 or 2 nucleotides in the AS-ODN resulted in less effective inhibition of both cell viability and VEGF protein secretion in vitro. Cellular uptake of ODNs is highly variable and limited because of their negative charge.59We determined that AS-3 was indeed taken up by the cells and largely localized to the nuclei. The possibility that the AS-3 mutants were not active because of lack of cellular uptake can be discounted because an intracellular fluorescent signal from these ODNs was also observed, predominantly in the nuclei. Pattern- recognition receptors may be responsible for the uptake of certain ODNs.60 61 The mechanism of VEGF AS-3 uptake via a receptor pathway is under investigation.

Modification of VEGF AS-3 to generate an MBO (AS-3m) in which a portion of the ODN on each end was replaced with 2′-O-methylribonucleosides retained specific activity and also allowed oral delivery.39 Daily dosing with AS-3m strongly inhibited the growth of melanoma, ovarian carcinoma, and Kaposi sarcoma tumor xenografts and orthotopic prostate carcinoma in nude mice. As additional proof that AS-3m acts in vivo in a VEGF-specific manner, serum VEGF levels derived from tumor (hVEGF) were reduced in a dose-dependent manner in Hey ovarian xenograft–bearing mice. All the cell lines used in the xenografts (KS Y-1, M21, Hey) were also VEGFR-1+ and VEGFR-2+ and shown to be growth-inhibited by AS-3 in vitro. In these models both the tumor and endothelial cells are potential targets for AS-3m. TUNEL assays on ovarian xenograft tumors showed apoptosis of tumor cells distant from blood vessels and perivascular apoptotic cells, a finding that is consistent with our hypothesis.

Tumors have evolved many mechanisms to evade the immune system, one of which is the inhibition of dendritic cell maturation by VEGF.62 We observed infiltration of leukocytes into the orthotopic prostate tumors in animals that were treated with AS-3m, whereas in untreated mice leukocytes did not infiltrate actively growing tumor tissue. Presumably, this is in part due to decreased VEGF in the treatment group. Characterization of the infiltrating leukocytes is under investigation.

Phosphorothioate ODNs can elicit both an innate and adaptive immune response,63 particularly if they contain the sequence 5′-PuPuCGPyPy-3′. AS-3m does contain a CG pair; however, this is not in the context of the flanking purines and pyrimidines. To exclude purely immune stimulatory functions from the action of AS-3m in vivo, Hey ovarian tumor xenografts were implanted in SCID beige mice. In this mouse model, which lacks B and T lymphocytes and has nonfunctional NK cells and monocytes, AS-3m was an effective inhibitor of tumor growth. The in vivo antitumor activity of AS-3m is therefore not accounted for by immune stimulation by the ODN.

In conclusion, we have shown that various human tumor cell lines express both VEGF and VEGFRs. In these tumor cell lines VEGF is an autocrine growth factor, such that inhibitors of VEGF or VEGFRs compromise the viability of the tumor cells. It is easy to screen tumors that express VEGFRs by various techniques, including immunocytochemistry, in situ hybridization, laser-assisted microdissection of the tumor region, and amplification of short stretches of mRNA. We propose that expression of VEGFRs will influence the biological behavior of the tumor. Furthermore, screening of the tumors prior to therapy may provide prognostic value. Lastly, inhibition of VEGF or VEGFR signaling would inhibit both tumor angiogenesis and tumor cell growth and viability when there is evidence of VEGFR expression in the tumor cells.

We thank Ernesto Barron for expert assistance with the confocal microscopy and Shikun He for performing the TUNEL staining. Sudhir Agrawal provided the AS-3m MBO and invaluable discussion.

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant 1R01 CA 79218, the Lynne Cohen Foundation and the Ezralow Family Foundation (P.S.G.), University of California UARP grant K99 USC-054 (R.M.), and the USC/Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center confocal core grant P30 CA14084-26 from the National Institutes of Health.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Parkash S. Gill, Professor of Medicine and Pathology, USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, Rm 3458, 1441 Eastlake Ave MC 9172, Los Angeles, CA 90033; e-mail:parkashg@hsc.usc.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal