We studied the degree and the pattern of skewing of the variable region of β-chain (VB) T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoire in aplastic anemia (AA) at initial presentation and after immunosuppression using a high-resolution analysis of the TCR VB complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3). Age-matched healthy individuals and multitransfused patients with non–immune-mediated hematologic diseases were used as controls. In newly diagnosed AA, the average frequency of CDR3 size distribution deviation indicative of oligoclonal T-cell proliferation was increased (44% ± 33% vs 9% ± 9%; P = .0001); AA patients with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–DR2 and those with expanded paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria clones showed more skewed VB repertoires. Nonrandom oligoclonal patterns were found for VB6, VB14-16, VB21, VB23, and VB24 subfamilies in more than 50%, and for VB15, VB21, and VB24 in more than 70% of AA patients with HLA-DR2. Patients received immunosuppression with antithymocyte globulin (ATG)/cyclosporine (CsA) or cyclophosphamide (CTX) with CsA in combination, and their VB repertoire was reanalyzed after treatment. Whereas no significant change in the degree of VB skewing in patients who had received ATG was seen, patients treated with CTX showed a much higher extent of oligoclonality within all VB families, consistent with a profound and long-lasting contraction of the T-cell repertoire. VB analysis did not correlate with the lymphocyte count prior to lymphocytotoxic therapy; however, after therapy the degree of VB skewing was highly reflective of the decrease in lymphocyte numbers, suggesting iatrogenic gaps in the VB repertoire rather than the emergence of clonal dominance. Our data indicate that multiple specific clones mediate the immune process in AA.

Introduction

Patients with aplastic anemia (AA) often respond to intensive immunosuppressive therapies, becoming transfusion-independent and no longer susceptible to infections.1 An immunologic mechanism of hematopoietic failure is supported by many laboratory studies.2 A role for T cells in AA was first suggested by coculture and depletion experiments, in which inhibition of hematopoietic colony formation was associated with lymphocytes.3 In general, experimental evidence indicates that both cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and Th1lymphocytes are the effector cells,3,4 and several effector Th1 mechanisms have been described including interferon-γ–mediated inhibition and Fas-induced apoptosis of hematopoietic progenitors.5-7 Marrow localization of pathophysiologic T cells has been observed in vitro8,9 and in vivo.10 Recently, polymorphisms within the complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) of the variable beta (VB) chain of the T-cell receptor (TCR) have been utilized for the study of immune mechanisms in AA.11-13 TCR VB CDR3 is a nongermline encoded hypervariable region directly related to T-cell recognition of specific peptides in the appropriate human leukocyte antigen (HLA) context. CDR3 thus defines a unique clonotype generated by a somatic rearrangement, resulting in discrete amino acid differences within each VB chain. Deviation from the normal size distribution in the CDR3 cDNA fragments generated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) corresponds to antigen-driven T-cell clonal expansion and may reflect, for example, overrepresentation of a specific TCR idiotype.14,15Analysis by spectratyping (high-resolution CDR3 analysis) of murine TCR VB showed that the normal T-cell response is relatively restricted to one or a few CDR3 size peaks, corresponding to a few dominant T-cell clones.16 Skewing of the T-cell VB spectrum has also been described for animal models of immunologically mediated diseases such as encephalitis17,18 and thyroiditis.19 In humans, expansion of specific CDR3 VB TCR clones has been found in type I diabetes mellitus,20 thyroiditis,21rheumatoid arthritis,22-24 primary biliary cirrhosis,25 psoriasis,26,27 or during graft-versus-host disease.28

TCR VB repertoire analysis has also been performed in patients with AA,12,13 myelodysplasia (MDS),29 and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH).30 In one study of severe AA, a broadly normal VB distribution pattern with overexpression of a few VB types indicative of selective CDR3 usage was observed, but skewing was not limited to specific VB families, perhaps due to different HLA backgrounds, and analysis of the J regions excluded monoclonality.12 In cyclosporine A (CsA)-dependent AA, in contrast to refractory cases, a significantly skewed CDR3 size pattern was found and all patients shared the HLA-DRB1*1501 genotype13; in addition, VB15 CDR3 sequencing showed dominant clones in 5 patients. An abnormal T-cell repertoire has also been found in PNH, which often accompanies typical AA and may share with it some aspects of an autoimmune pathophysiology.30 Based on VB identity, individual helper31 and cytotoxic32 T-cell clones have been generated and functionally characterized as specific for hematopoietic target cells. A study from our laboratory described a CD4 clone derived from AA bone marrow (BM) and capable of a specific cytotoxity and inhibition of colony formation by the patient's CD34+ cells. VB5.1 CDR3 genotype of this clone was shared among other patients with AA with similar clinical features.33 These data suggest that a specific CDR3 sequence is the signature of a pathogenic T-cell clone contributing to BM failure. Immunosuppressive therapy reduced but did not eradicate the clone, consistent with the notoriously high rate of relapse. We concluded that fine analysis of CDR3 may serve to distinguish specific subsets of marrow failure and for identification of common offending antigens.

Here we have systematically analyzed VB CDR3 TCR repertoire changes in a series of patients with AA at initial presentation and after immunosuppression in order to identify characteristic skewing patterns and factors influencing changes in the T-cell clonotypic repertoire in AA.

Materials and methods

Patients and control populations

Peripheral blood (PB) was obtained through venipucture of healthy volunteers and patients with acquired AA into syringes containing media supplemented 1:10 with heparin (O'Neill and Feldman, St Louis, MO). Informed consent was obtained according to protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Bethesda, MD). PB mononuclear cells (PBMNCs) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using lymphocyte separation medium (Organon, Durham, NC). After washing in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS; Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD), cells were resuspended in Iscoves modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM; Gibco-BRL, Bethesda, MD) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum (FCS; Life Technologies).

We analyzed a total of 33 samples from 15 patients with severe AA (Table 1). In 13 patients, a set of 2 samples was analyzed: one sample from initial presentation and the other from 3 months after receiving immunosuppressive therapy. In 5 patients (of 13 followed), additional serial samples between 1 and 2 years after immunosuppressive treatment (see below) were studied. The diagnosis of AA was established by BM biopsy and PB cell counts according to the International Study of Aplastic Anemia and Agranulocytosis; severity was classified by the criteria of Camitta et al.34 No evidence for hereditary marrow failure syndromes was found. Except for one patient with history of thymoma at presentation, no specific etiologies were identified by patient history (such as toxic exposures, medical drugs, and viral infections including seronegative hepatitis) and all cases appeared to be idiopathic. For the diagnosis of severe AA (sAA), in addition to hypocellular BM without evidence of karyotypic abnormalities or morphologic dysplasia, patients had to fulfill 2 out of 3 PB criteria: absolute neutrophil count (ANC) less than 500/μL, absolute reticulocyte count (ARC) of less than 40 000/μL, and platelet count of less than 20 000/μL of blood. Clinical characteristics of the patients studied are summarized in Table 1. Their median age was 42 years (range, 9-57). Following initial evaluation, all patients were treated with immunosuppression except for 2 (14 and 15) who had histories of refractoriness to ATG and received combined granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and stem cell factor (SCF). Immunosuppressive therapy consisted either of antithymocyte-globulin/cyclosporine A/mycophenolate mofetil (ATG/CsA/MMF; 40 mg/kg per day of horse ATG × 4 days plus MMF at 2 g per day for 1 year plus CsA at 12 mg/kg per day × 6 months started on day 10; n = 8), ATG/CsA regimen without MMF (n = 2), or cyclophosphamide (CTX)/CsA (60 mg/kg per day of CTX × 4 days, followed by CsA at 12 mg/kg per day × 6 months; n = 3).35 36 Patients were also subgrouped according to the presence of particular HLA alleles such as HLA-A2 (HLA-A*02) and HLA-DR2 (HLA-DRB1*15).

Clinical characteristics of patients with aplastic anemia

| . | Age (y) . | HLA . | PNH . | Therapy . | PB counts at presentation . | PB counts at 3 months . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A*02 . | DRB1*15 . | ANC . | ALC . | Hgb . | ARC . | Ptl . | ANC . | ALC . | Hgb . | ARC . | Ptl . | ||||

| 1 | 30 | Y | N | N* | Ctx/CsA | 1 200 | 2 498 | 9.2 | 2 | 19 | 2 048 | 1 305 | 8.6 | 38 | 26 |

| 2 | 46 | N | Y | 1.7% | ATG/CsA | 1 800 | 3 113 | 7.9 | 65 | 15 | 3 400 | 2 899 | 12 | 73 | 69 |

| 3 | 36 | N | Y | 7.6% | ATG/CsA | 560 | 2 200 | 7.7 | 46 | 25 | 886 | 1 733 | 11.8 | 85 | 83 |

| MMF | |||||||||||||||

| 4 | 57 | N | Y | 7.7% | ATG/CsA | 526 | 1 469 | 8 | 32 | 19 | 1 342 | 126 | 10.1 | 80 | 57 |

| MMF | |||||||||||||||

| 5 | 15 | N | N | N | ATG/CsA | 113 | 1 942 | 9.5 | 1 | 14 | 1 480 | 1 085 | 9.2 | 31 | 58 |

| MMF | |||||||||||||||

| 6 | 9 | Y | N | N | ATG/CsA | 403 | 1 541 | 7.8 | 28 | 23 | 627 | 1 299 | 10.5 | 85 | 57 |

| MMF | |||||||||||||||

| 7 | 51 | Y | Y | N | ATG/CsA | 22 | 433 | 9.1 | 4 | 12 | 4 797 | 1 151 | 10.3 | 52 | 93 |

| MMF | |||||||||||||||

| 8 | 48 | Y | N | N | Ctx/CsA | 437 | 3 015 | 10.3 | 10 | 60 | 1 530 | 459 | 8.4 | 58 | 24 |

| 9 | 28 | Y | Y | N | ATG/CsA | 279 | 2 540 | 8.2 | 17 | 9 | 5 768 | 1 694 | 11.9 | 66 | 284 |

| MMF | |||||||||||||||

| 10 | 54 | N | Y | N | ATG/CsA | 21 | 2 006 | 10.2 | 6 | 45 | 297 | 2 544 | 8.8 | 42 | 57 |

| 11 | 47 | N | Y | 15% | ATG/CsA | 287 | 1 900 | 9.1 | 39 | 30 | 1 279 | 1 300 | 7.2 | 73 | 13 |

| MMF | |||||||||||||||

| 12 | 50 | N | Y | 6.5% | ATG/CsA | 160 | 1 364 | 7.7 | 14 | 8 | 954 | 1 200 | 9.4 | 126 | 12 |

| 13 | 38 | Y | N | N | Ctx/CsA | 765 | 682 | 8.2 | 15 | 2 | 1 066 | 391 | 9 | 23 | 30 |

| 14 | 56 | Y | Y | N | G-CSF/SCF | 11 900 | 3 600 | 10.2 | 10 | 11.9 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 15 | 35 | N | N | 76% | G-CSF | 906 | 1 567 | 9.7 | 180 | 48 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| . | Age (y) . | HLA . | PNH . | Therapy . | PB counts at presentation . | PB counts at 3 months . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A*02 . | DRB1*15 . | ANC . | ALC . | Hgb . | ARC . | Ptl . | ANC . | ALC . | Hgb . | ARC . | Ptl . | ||||

| 1 | 30 | Y | N | N* | Ctx/CsA | 1 200 | 2 498 | 9.2 | 2 | 19 | 2 048 | 1 305 | 8.6 | 38 | 26 |

| 2 | 46 | N | Y | 1.7% | ATG/CsA | 1 800 | 3 113 | 7.9 | 65 | 15 | 3 400 | 2 899 | 12 | 73 | 69 |

| 3 | 36 | N | Y | 7.6% | ATG/CsA | 560 | 2 200 | 7.7 | 46 | 25 | 886 | 1 733 | 11.8 | 85 | 83 |

| MMF | |||||||||||||||

| 4 | 57 | N | Y | 7.7% | ATG/CsA | 526 | 1 469 | 8 | 32 | 19 | 1 342 | 126 | 10.1 | 80 | 57 |

| MMF | |||||||||||||||

| 5 | 15 | N | N | N | ATG/CsA | 113 | 1 942 | 9.5 | 1 | 14 | 1 480 | 1 085 | 9.2 | 31 | 58 |

| MMF | |||||||||||||||

| 6 | 9 | Y | N | N | ATG/CsA | 403 | 1 541 | 7.8 | 28 | 23 | 627 | 1 299 | 10.5 | 85 | 57 |

| MMF | |||||||||||||||

| 7 | 51 | Y | Y | N | ATG/CsA | 22 | 433 | 9.1 | 4 | 12 | 4 797 | 1 151 | 10.3 | 52 | 93 |

| MMF | |||||||||||||||

| 8 | 48 | Y | N | N | Ctx/CsA | 437 | 3 015 | 10.3 | 10 | 60 | 1 530 | 459 | 8.4 | 58 | 24 |

| 9 | 28 | Y | Y | N | ATG/CsA | 279 | 2 540 | 8.2 | 17 | 9 | 5 768 | 1 694 | 11.9 | 66 | 284 |

| MMF | |||||||||||||||

| 10 | 54 | N | Y | N | ATG/CsA | 21 | 2 006 | 10.2 | 6 | 45 | 297 | 2 544 | 8.8 | 42 | 57 |

| 11 | 47 | N | Y | 15% | ATG/CsA | 287 | 1 900 | 9.1 | 39 | 30 | 1 279 | 1 300 | 7.2 | 73 | 13 |

| MMF | |||||||||||||||

| 12 | 50 | N | Y | 6.5% | ATG/CsA | 160 | 1 364 | 7.7 | 14 | 8 | 954 | 1 200 | 9.4 | 126 | 12 |

| 13 | 38 | Y | N | N | Ctx/CsA | 765 | 682 | 8.2 | 15 | 2 | 1 066 | 391 | 9 | 23 | 30 |

| 14 | 56 | Y | Y | N | G-CSF/SCF | 11 900 | 3 600 | 10.2 | 10 | 11.9 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 15 | 35 | N | N | 76% | G-CSF | 906 | 1 567 | 9.7 | 180 | 48 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

HLA indicates human leukocyte antigen; PNH, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria; ANC, absolute neutrophil count (/μL); ARC, absolute reticulocyte (/μL); ALC, absolute lymphocyte count (/μL); Hgb, hemoglobin (g/dL); Ptl, platelets (× K/μL); Y, yes; N, no; Ctx, cyclophosphamide; CsA, cyclosporine; ATG, antithymocyte globulin; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; SCF, stem cell factor.

PNH granulocytes were measured as described in “Materials and methods.” The cut-off limit for the diagnosis of PNH clone was 1%.

Patients were classified as responders when they no longer fulfilled the severity criteria and became transfusion-independent according to previously published criteria.35 By these parameters, all 13 patients responded to immunosuppressive therapy.

PNH/AA syndrome

The presence of a PNH clone was determined using flow cytometry: the test was considered positive when more than 1% of glycosyl phosphatidylinositol–anchored protein (GPI-AP)–deficient neutrophils in blood were found, as defined by negativity for surface staining for CD66b and CD16 in a distinctive population of CD15+ cells. For the purpose of this study, patients with the presence of the PNH clone and otherwise fulfilling criteria of sAA or mAA were classified as having AA/PNH.37

Five transfusion-dependent patients with hemoglobinopathies (median age 40 years: range, 19-49; 1 female, 4 males) and 14 age-matched, healthy individuals (median age 44 years, range, 8-56) were used as controls.

RNA isolation and complementary DNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from 1 × 106 to 2 × 106 PBMCs with TRIzol reagent (Gibco-BRL). The SuperScript II RT kit (Gibco-BRL) was employed for first strand complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis. Briefly, 1 unit of SuperScript II Rnase H-reverse transcriptase was used in the presence of 1 μg RNA, 0.5 μg/μL of oligo(dT)12-18 at 42°C for 50 minutes and in a final volume of 20 μL.

Polymerase chain reaction and CDR3 size distribution analysis

Details of the CDR3 size distribution assay have been reported, including reaction conditions and primer sequences.15,38Briefly, cDNA was amplified using PCR with TCR VB family-specific primer and an antisense TCR constant β-chain (CB) common primer.39 A quantity of 2 μL of 10X buffer (Takara Biomedicals, Shiga, Japan) containing 15 μM MgCl2, 1.7 μL dNTP (2.5 mmol each), 5 μL of 20 μM of each VB subfamily sense primer, 1 μL of 20 μM fluorescent CB primer, 1 μL cDNA, and 0.18 μL of 5 U/μL of TaKaRa Ex Taq (Takara Biomedicals) was mixed in a final volume of 20 μL. PCR was performed in a Peltier Thermal Cycler-200 (MJ Research, Waltham, MA) under the following conditions: 15 cycles of initial touchdown was done by denaturation at 94°C for 1 minute, followed by annealing of primers at 60°C for 1 minute with −0.5°C gradient reduction of annealing temperature for the subsequent cycles to 53°C, and extension at 72°C for 1 minute. Subsequently, 20 additional amplification cycles (denaturation at 94°C for 1 minute, followed by annealing at 53°C for 1 minute, and extension at 72°C for 1 minute) were performed with a final extension of the primers at 72°C for 10 minutes. Subsequently, 1 μL of amplification products was mixed with 12.5 μL deionized formamide (Sigma) and 0.5 μL size standard (Genescan-400 ROX, ABI 310; Perkin-Elmer, Shelton, CT), heated at 90°C for 2 minutes, chilled on ice, and applied to an ABI 310 sequencer to analyze the CDR3 size distribution.

Statistical analysis

To classify each individual profile as normal or abnormal (skewed), we adopted a set of numerical standards. The fluorescence intensity of each band was depicted as peaks. CDR3 size patterns that failed to exhibit a bell-shaped distribution due to the appearance of prominent peaks with or without a reduced peak number (< 5 peaks) were judged as abnormal.13 The analysis was performed by 3 different investigators in blinded fashion, and in a few cases where inconsistent results were obtained the decision as to whether the pattern is skewed or abnormal was based on the agreement of 2 out of 3 investigators. The frequency of VB subfamilies displaying an abnormal CDR3 size profile was determined in each subject. For each VB subfamily, the overall frequency of skewing within test groups was evaluated. Nominal Fisher exact test P values were calculated for the comparison of the frequency of skewed TCR VB family profiles. The Student t test was used to compare differences in the mean frequency of skewed TCR VB families between the groups. All analyses were performed using Medcalc software (Medcalc, Mariakerke, Belgium).

Results

TCR CDR3 size distribution analysis in normal and hematologic controls

To analyze the VB repertoire in a cohort of patients with AA (Table 1), RNA was extracted from PB lymphocytes and cDNA synthesized. cDNAs for 21 different TCR VB subfamilies were amplified using a set of VB primers and a fluorescent CB primer. TCR VB10 and VB19 are pseudogenes and were excluded from the study40; the VB17 subfamily was also excluded because we were unable to reliably obtain amplification products and/or the size fractionation of the PCR products failed to produce profiles with adequate signal-to-noise ratios. Patterns of VB size distribution were compared between patients (n = 15), age-matched healthy controls (n = 14), and multiply transfused hematologic controls (n = 5; examples shown in Figure1). No significant differences (12% ± 9% vs 7% ± 5%) were seen in the pattern of VB skewing between healthy controls (n = 14) and multiply transfused hematologic controls (n = 5) and therefore in further comparisons the control groups were combined (9% ± 9%). For instance, in the control sample N2, shown in Figure 1, skewing of the size profile is present only with VB11 amplification product resulting in the calculated frequency of VB skewing of about 5% (1/21).

VB skewing in healthy controls and patients with aplastic anemia.

In patients with AA, CDR3 size distribution patterns were compared before and after immunosuppressive therapy. ATG indicates antithymocyte globulin. Fluorescence intensity versus molecular weight.

VB skewing in healthy controls and patients with aplastic anemia.

In patients with AA, CDR3 size distribution patterns were compared before and after immunosuppressive therapy. ATG indicates antithymocyte globulin. Fluorescence intensity versus molecular weight.

Degree of VB skewing in patients with AA

When the proportion of unevenly distributed VB patterns (per VB family) in patients with sAA was compared with the control group, samples obtained prior to therapy showed a higher proportion of skewed VB-profiles (44% ± 33% vs 9% ± 9%; P = .0001; Figure1, Figure 2). No correlation between age and the degree of VB skewing was found before immunosuppression. As the degree of VB skewing could be related to the duration of cytopenia itself rather than to an autoimmune process, we compared patients with disease duration of less than 6 months (n = 12) and those whose initial diagnosis was more than 2 years prior to blood sampling; there was a significant difference in the percentage of skewed VB families (31% vs 74%; P = .04). However, in the latter group, 2 patients had refractory disease and the difference may not be due to the time elapsed from initial diagnosis. To determine whether a specific HLA type was associated with VB skewing, patients with specific alleles, found at high frequency in AA, were analyzed separately (Figure 2). Patients with HLA-DR2 (56% ± 35%;P < .0001) and those with HLA-A2 (37% ± 29%;P = .001) had a higher degree of VB skewing than did age-matched controls (no normal control group matched for HLA type was available). Similarly, a higher proportion of skewed VB families was found in patients with AA with an expanded PNH clone as compared with controls (AA/PNH; 52% ± 32%; P < .0001).

Skewing of VB repertoire in AA, described in percent of skewing among 21 VB subfamilies (mean±SD).

(A) Healthy controls. (B) New AA. (C) Patients with AA with HLA-DR2. (D) Patients with AA with HLA-A2. (E) Patients with PNH/AA. *P < .05; ** P < .01.

Skewing of VB repertoire in AA, described in percent of skewing among 21 VB subfamilies (mean±SD).

(A) Healthy controls. (B) New AA. (C) Patients with AA with HLA-DR2. (D) Patients with AA with HLA-A2. (E) Patients with PNH/AA. *P < .05; ** P < .01.

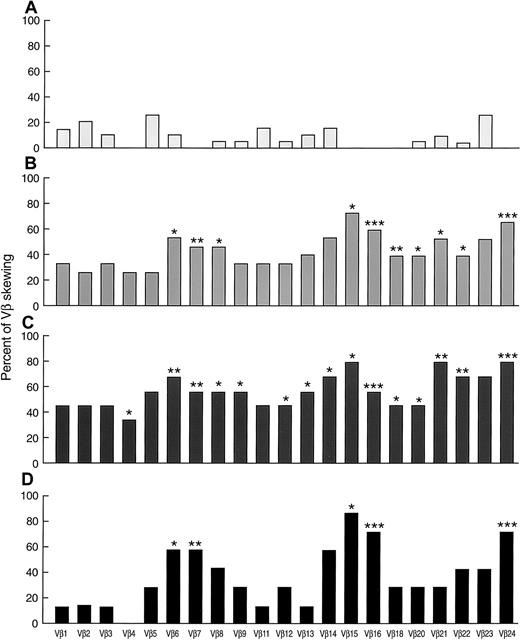

Patterns of VB skewing in AA

In addition to the overall proportion of skewed VB profiles, we examined specific patterns of CDR3 size distribution in patients with AA in order to identify individual VB clonotypes and subfamilies possibly involved in the disease process. In controls, the rate of skewing of specific VB subfamilies was variable from 0% (eg, 0/19 for VB16) to 26% (5/19 for VB23; Figure 3). None of the controls showed skewing in VB4, VB7, VB15, VB16, VB18, and VB24 (n = 19). In contrast, 27% and 73% of new patients with AA showed skewing in VB4 and VB15, respectively. Skewing of VB6, VB7, VB8, VB15, VB16, VB18, VB20, VB21, VB22, and VB24 subfamilies was found in a higher proportion of patients with AA in comparison to controls. Overall, VB6, VB14, VB15, VB16, VB21, VB23, and VB24 were found skewed in over 50% of untreated patients with AA. Skewing of VB14, VB15, and VB21-24 was found at an even higher rate when only patients with HLA-DR2 were studied. Patients with AA with HLA-DR2 also showed changes in the VB9, VB12, and VB13 size distribution profile more frequently. Less-pronounced differences were seen in the VB profiles of patients with AA with HLA-A2 alleles (Figure 3). In patients with AA/PNH syndrome, skewing of VB1, VB3, VB4, VB6, VB8, VB11-16, VB18, VB20, VB21, VB23, and VB24 was found in over 50% (data not shown). VB13 and VB21 were skewed in 83% of cases. In addition, we also observed more frequent skewing in VB4, VB8, VB12, VB13, VB16, VB18, VB20, and VB24 as compared with controls, and VB13 repertoire skewing was more frequent in AA/PNH than in AA without PNH (83% vs 11%;P = .02).

Skewing patterns of 21 individual VB subfamilies in AA.

(A) Healthy controls (n = 19). (B) New AA (n = 15). (C) Patients with AA with HLA-DR2 (n = 9). (D) Patients with AA with HLA-A2 (n = 7). * P < .05; ** P < .01; ***P < .001. All the significance levels were calculated in comparison with healthy controls.

Skewing patterns of 21 individual VB subfamilies in AA.

(A) Healthy controls (n = 19). (B) New AA (n = 15). (C) Patients with AA with HLA-DR2 (n = 9). (D) Patients with AA with HLA-A2 (n = 7). * P < .05; ** P < .01; ***P < .001. All the significance levels were calculated in comparison with healthy controls.

Immunosuppressive therapy and VB skewing

Of 15 patients analyzed, 12 were studied at presentation, 1 after relapse of AA (after successful ATG/CsA therapy), and an additional 2 who had been treated with ATG and CsA in the past but remained refractory. Of these patients, 13 received immunosuppressive therapy with either ATG/CsA, ATG/CsA/MMF, or CTX/CsA combination (Figure4, Figure5). All patients responded to the treatment with significant improvement of blood counts (see “Materials and methods”). When analyzed 3 months after the initiation of therapy, the ATG group (n = 10) showed no difference in degree of VB spectratype skewing as compared with pretreatment analysis (45% ± 36% vs 50% ± 29%; P = .75; Figure 4). Subsequently collected samples 2 years after therapy (n = 3) showed a preservation of the pattern in 2 patients and increased skewing in 1 patient (14% of skewing initially, 19% at 3 months, and 77% at 2 years). Some individual patients showed increases and others decreases in VB skewing after ATG treatment. Subsequent relapse was experienced in 3 of 10 responders to ATG. When the degree of residual skewing after therapy was compared between stable responders and those who relapsed, no significant difference was found.

Effect of immunosuppression on the skewing of VB repertoire (mean±SD).

The degree of skewing was compared before and after ATG or CTX treatment. (A) ATG-treated patients. (B) CTX-treated patients.

Effect of immunosuppression on the skewing of VB repertoire (mean±SD).

The degree of skewing was compared before and after ATG or CTX treatment. (A) ATG-treated patients. (B) CTX-treated patients.

Effect of immunosuppression on skewing patterns of 21 individual VB subfamilies in AA.

(A) Before ATG (n = 10). (B) After ATG (n = 10). (C) Before CTX (n = 3). (D) After CTX (n = 3).

Effect of immunosuppression on skewing patterns of 21 individual VB subfamilies in AA.

(A) Before ATG (n = 10). (B) After ATG (n = 10). (C) Before CTX (n = 3). (D) After CTX (n = 3).

In contrast, high-dose CTX therapy (n = 3) consistently increased the proportion of skewed VB profiles as compared with pretreatment values (27% ± 15% vs 87% ± 12%;P = .01). When CDR3 analysis was performed at 2 years after initial treatment in 2 patients who showed a stable hematologic response and normal lymphocyte counts, the oligoclonal skewing pattern seen after therapy was unchanged (in 1 patient, 33% of skewed VB families before therapy, 100% at 3 months, and 81% at 2 years; in the other patient, 9.5% of skewed VB classes before therapy, 76% at 3 months, and 90% at 2 years).

We also studied the effect of therapy on the patterns of VB skewing (Figure 5). In the ATG group (n = 10), skewing of VB15 was found less frequently after the therapy (from 70% to 40%), whereas a skewed VB9 profile was found more frequently (from 40% to 80%). In the CTX group (n = 3), the percentage of skewed population was increased in most of the VB subfamilies.

Correlation of VB repertoire with lymphocyte number

Changes in the VB CDR3 size distribution pattern might be due to the expansion of individual clones or, alternatively, loss of VB variability as a result of clonal or polyclonal deletion. Low lymphocyte counts occurring, for example, after lymphocytotoxic therapy could affect the VB spectratype, and we therefore sought a correlation between the degree of VB CDR3 size skewing and the absolute lymphocyte count. At presentation, no relationship between these 2 variables was found, but after immunosuppression there was an inverse correlation between the degree of VB size distribution skewing and lymphocytopenia (Figure 6).

Correlation of VB skewing with absolute lymphocyte number.

(A) Before immunosuppression. (B) After immunosuppression.

Correlation of VB skewing with absolute lymphocyte number.

(A) Before immunosuppression. (B) After immunosuppression.

Discussion

Using high-resolution VB CDR3 analysis, we found nonrandom skewing among the VB-chain families of the TCR. In AA, our results confirm those of others, examining smaller numbers of patients with AA.11-13 We went on to compare VB CDR3 skewing before and after immunosuppressive therapy. VB CDR3 skewing seen in AA was significantly increased compared with that of healthy and hematologic controls. VB CDR3 skewing can occur among healthy individuals (especially for CD8 T cells), suggestive of nonpathologic expansion of T-cell clones analagous to B-cell–derived monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance41; however, most of our patients were young, and additionally we employed an age-matched control group. The absence of VB CDR3 skewing in multiply transfused patients indicates that this finding is not a secondary phenomena in AA; in addition, our patients were not clinically infected at the time of sampling, making this also an unlikely cause of our results.

The specific patterns of VB CDR3 skewing observed in AA suggested that certain VB families were more likely to be affected in this disease. Some of the same VB families were also noted to be abnormal in other studies.11-13,29 30 The VB patterns of AA are clearly different from the monoclonal expansion seen in diseases like large granular lymphocytic leukemia, as many clones seem to be involved in the pathophysiologic immune response in AA. The particular VB families involved must be dependent on the HLA alleles of the patients, and histocompatibility heterogeneity precludes the finding of a consistent “signature” clone within a specific VB subfamily for all patients. As our spectratyping analysis was performed on RNA obtained from total lymphocytes, some expansions may not have been detected due to the overlap of CD4 and CD8 spectratypes that are restricted by HLA class I or class II alleles, respectively. Conversely, some artificial skewing might occur due to the coincidental superimposition of CD4 and CD8 specific size distribution patterns. Despite these concerns, we were able to detect consistent skewing within certain specific VB families in up to 70% of all patients with AA, strongly suggestive of their involvement as disease-specific clonal expansions.

Asymmetric or oligoclonal patterns of VB CDR3 size distribution could result from either clonal expansion or a global decrease in TCR variability. Furthermore, if the skewing was reflective of an underlying pathophysiology, therapy would be expected to influence the pattern. For example, normalization of a clonally skewed spectratype might correspond to diminution or disappearance of a pathophysiologic clone. It was therefore surprising that there were no consistent changes in skewing following ATG therapy; some patients demonstrated increased skewing within certain families and decreased skewing in others. In contrast, high-dose cyclophosphamide dramatically increased the pattern of skewing in all patients treated with this therapy. In this circumstance, the skewing pattern appeared to reflect the lymphocytotoxic nature of the treatment. There was a strong correlation in this circumstance between the degree of skewing and the lymphocyte number in the PB. Similar defects in the T-cell repertoire regularly occur after BM transplantation and are likely responsible for much of the infectious complications of this procedure leading to transplant-related mortality.42 Lack of normalization of increased oligoclonal skewing within VB subfamilies after successful ATG treatment may weaken the relationship between VB changes and an autoimmune pathophysiology of AA. However, global changes observed in this and other studies11-13,29 30 may result from a sum of diverse processes and circumstances such as autoimmunity, degree and duration of lymphopenia itself, HLA background, age, and comorbidities. Therefore, more intricate analysis may be needed to characterize disease-specific clones. For instance, adjustment for the cell count, separate analysis of CD4 and CD8 subsets or activated and/or effector subpulations, as currently performed in our laboratory, may be required to detect and correlate spectratyping results with pathophysiology as well as clinical features.

Skewing of a specific VB spectratype, while consistent with oligoclonality, requires confirmation by sequencing of the specific CDR3 region, including the J regions, or determination of the J types by PCR. Since as many as 13 J primers can combine with each VB subfamily member, these experiments would greatly add to the complexity of the analysis.38 Nevertheless, the presence of VB skewing indicates a preferential usage and/or expansion of a limited number of T-cell clones, and its nonrandom nature is consistent with a dominant selective antigenic drive in the disease process. In this respect, VB skewing serves as a surrogate marker, analogous to the presence of autoantibodies in other immune-mediated diseases. Even an initial immune response, to a single antigen, may result in activation of multiple T-cell clones; for a single antigen, the nature of the dominant clone may shift over time. Furthermore, through antigenic spread, new cryptic epitopes may be revealed, leading to a shift in the T-cell response. We and others have observed true oligoclonal expansion on J-regional analysis in limited numbers of patients with AA.13,30,33 The usage of a particular clonal type depends not only on the identity of the antigen but also on HLA restriction. For all of these reasons, true clonality in an autoimmune disease is not expected. Indeed, oligoclonality has been reported in studies of experimental autoimmunity in animals17-19 as well as in human rheumatoid arthritis,22-24 systemic lupus erythematosus,43,44 and IgA nephropathy.45Clonal dominance also occurs in viral infection46-48 and in response to tumors and during graft-versus-host disease.28,49-51 Polyclonal immune response also occurs after vaccination.40 The heterogeneity in the pattern of VB CDR3 size profiles in AA argues against overwhelming clonal amplification of a specific dominant T cell at the onset of the disease.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Jaroslaw P. Maciejewski, Experimental Hematology and Hematopoiesis, Taussig Cancer Center / R40, 9500 Euclid Ave, Cleveland, OH 44195; e-mail: maciejj@cc.ccf.org.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal