Morphologic studies have demonstrated a process by which α-granule contents are released from platelets. Studies aimed at defining the molecular mechanisms of this release have demonstrated that SNARE proteins are required for α-granule secretion. These observations raise the possibility that morphologic features of α-granule secretion may be influenced by the subcellular distribution of SNARE proteins in the platelet. To evaluate this possibility, we analyzed the subcellular distribution of 3 functional platelet SNARE proteins—human cellubrevin, SNAP-23, and syntaxin 2. Exposure of streptolysin O-permeabilized platelets to antihuman cellubrevin antibody inhibited Ca++-induced α-granule secretion by approximately 50%. Inhibition of α-granule secretion by antihuman cellubrevin was reversed by a blocking peptide. Syntaxin 2 and SNAP-23 have previously been demonstrated to mediate platelet granule secretion. The subcellular localization of the 3 SNARE proteins was determined by ultrastructural studies, using a pre-embedding immunonanogold method, and by immunoblot analysis of subcellular fractions. Immunonanogold localization demonstrated that approximately 80% of human cellubrevin in resting platelets was localized to platelet granule membranes. In contrast, SNAP-23 localized predominantly to plasma membrane, whereas syntaxin 2 was more evenly distributed among membranes of α-granules, the open canalicular system, and plasma membrane. Thus, each of these SNARE proteins has a distinct subcellular distribution in platelets, and each of these membrane compartments demonstrates a unique SNARE protein composition. This distribution provides a basis for several characteristics of α-granule secretion that include homotypic α-granule fusion and the fusion of α-granules with the open canalicular system and plasma membrane.

Introduction

Platelets demonstrate a number of characteristics that render them an important model of membrane trafficking. They are anucleate, display rare strands of endoplasmic reticulum, do not have Golgi structures, and synthesize little new protein. They are thought to undergo just one round of granule secretion following activation because they do not have adequate synthetic capacity to generate new granules. Although receptor-mediated1,2 and pinocytotic3 endocytosis have been observed in platelets, constitutive coupled endocytosis–exocytosis cycles that occur in nucleated cells in general4-8 and in hematopoietic cells in particular9 have not been documented in platelets. Thus, the degree to which generalizations regarding the molecular mechanisms of membrane trafficking can be applied to the platelet is uncertain. A second distinctive characteristic of the platelet is that its limiting membrane is characterized by a system of tunneling invaginations of the plasma membrane, termed the open canalicular system (OCS).10,11 Evidence that the OCS is open to the extracellular environment is derived from reports using various cell-impermeant tracers.12 The fate of the OCS on platelet activation is the subject of debate. There is evidence that the OCS undergoes evagination during platelet activation that provides an extra membrane for the formation of pseudopodia.13,14 Others have shown that the OCS becomes dilated and acts as a conduit to allow the exit of α-granule contents.12 15-17

Platelets also undergo a dramatic shape change following activation that is associated with the centralization of granules and the appearance of masses of cytoplasmic actin filaments. These observations have led to speculation that cytoskeletal reorganization is responsible for granule release. However, the inhibition of actin polymerization18 or microtubule organization19,20 does not inhibit granule secretion. Furthermore, granule secretion and shape change can be dissociated under several experimental conditions.21-23 Morphologic aspects of activation-dependent membrane fusion have been studied in detail. Platelet granules appear to undergo homotypic fusion on activation,24 a phenomenon observed in other cells of hematopoietic origin.25 Several studies demonstrate that α-granules may be secreted through fusion of the α-granule membrane with membranes of the OCS.12,15 Some evidence also suggests that the fusion of compound α-granules with the plasma membrane functions as a mode of exodus for the α-granule.13 26

More recently, studies evaluating the molecular mechanisms of platelet membrane fusion have demonstrated a role for SNARE proteins in these regulated secretory events.27,28 We29 and others30,31 have demonstrated SNARE proteins in platelets. The tSNAREs syntaxin 2, syntaxin 4, and syntaxin 729-32and SNAP-2329,31,32 are found in platelets. Platelets also contain gene products of the VAMP family of vSNAREs29including a novel VAMP isoform, termed human cellubrevin.33 The function of SNARE proteins that constitutes the trimeric exocytotic complex in platelet α-granule secretion has been evaluated using permeabilized platelet secretory models.29,32,34 Both antibodies directed against VAMP family proteins and tetanus toxin, a metalloproteinase that specifically cleaves VAMP,35 inhibit Ca++-induced secretion of α-granules.29 A functional role for human cellubrevin, however, has not previously been demonstrated in platelets. Antibodies directed at syntaxins 2 and 4 inhibit α-granule secretion from permeabilized platelets.29,34 Anti–SNAP-23 antibody also inhibits α-granule secretion.34 These functional data provide compelling evidence that SNARE proteins are essential for mediating the membrane fusion events involved in the secretion of platelet α-granules.

To determine whether the subcellular localization of functional SNARE proteins could account for the unusual character of platelet granule secretion, we sought to determine the subcellular localization of 3 functional SNARE proteins of the trimeric exocytotic complex. We first found that human cellubrevin participates in platelet α-granule secretion. We therefore determined the localization of this VAMP isoform along with SNAP-23 and syntaxin 2, 2 t-SNARE proteins known to mediate platelet granule secretion. Ultrastructural immunonanogold labeling and subcellular fractionation demonstrated that human cellubrevin is localized primarily to α-granule membranes in resting platelets. In contrast, SNAP-23 is localized primarily to plasma membranes in resting platelets, though some staining of membranes of the OCS and of granules can be appreciated by immunonanogold staining. Syntaxin 2 is distributed relatively evenly between the plasma membrane, the OCS, and granules in resting platelets. These data provide a potential mechanism by which homotypic α-granule fusion and α-granule fusion with the OCS and plasma membrane can occur, resulting in the secretion of α-granule proteins from platelets.

Materials and methods

Materials

All buffer constituents, MgATP, CaCl2, aspirin, prostaglandin E1 (PGE1), apyrase, and metrizamide were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Sepharose 2B and14C-serotonin were obtained from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ). Reduced streptolysin O (SL-O) was purchased from Corgenix (Peterborough, England). Sulfo-succinimido-biotin (sulfo-NHS-biotin) and dialysis cassettes were obtained from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Avidin–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). Tetanus toxin was obtained from List Biologics (Campbell, CA). All solutions were prepared using water purified by reverse-phase osmosis on a Millipore (Bedford, MA) Milli-Q Purification Water System.

Antibodies

Antihuman cellubrevin antibody was generated in our laboratory by immunizing rabbits with a peptide consisting of the 12 N-terminal amino acids of human cellubrevin. The amino acid sequence of the peptide is unique to human cellubrevin and is identical to that previously used to generate antibodies specific for human cellubrevin.33 Antibody was purified from immune serum by affinity chromatography. An anti-VAMP antibody directed at residues 36 to 56 of rat VAMP 2 was obtained from StressGen Biotechnologies (Victoria, BC, Canada). VAMP 1 and human cellubrevin are 95% homologous to VAMP 2 within the amino acid region on which the synthetic peptide is based. SNAP-23 antiserum, obtained from Synaptic Systems (Göttingen, Germany), is a rabbit polyclonal serum raised against the C-terminal end of SNAP-23 that has been previously characterized.29 Anti–syntaxin 2 antibody is an affinity-purified goat polyclonal antibody obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) that is directed against a 19–amino acid portion of the C-terminus in the cytoplasmic domain of syntaxin 1A. The antibody reacts with syntaxins 1A, 1B, 2, and 3. Of these syntaxin isoforms, only syntaxin 2 is found in platelets.32 The antibody does not react with syntaxin 4 or 7. Monoclonal antibody (clone CLB-gran/12) directed at human CD63 was obtained from Caltag Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). Antibody against the P-selectin cytoplasmic tail was described previously.29 Phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated mouse monoclonal anti–P-selectin antibody AC1.2 was purchased from Becton Dickinson (San Jose, CA).

Platelet preparation

Blood from healthy donors who had not ingested aspirin in the 2 weeks before donation was collected by venipuncture into 0.4% sodium citrate. Citrate-anticoagulated blood was centrifuged at 200g for 20 minutes to prepare platelet-rich plasma. Platelet-rich plasma was then used for ultrastructural studies as described below. For platelet secretion studies, platelets were purified from platelet-rich plasma by gel filtration using a Sepharose 2B column equilibrated in PIPES–EGTA buffer (25 mM PIPES, 2 mM EGTA,137 mM KCl, 4 mM NaCl, 0.1% glucose, pH 6.4). Final gel-filtered platelet concentrations were 1-2 × 108 platelets/mL. Platelet-rich plasma used for subcellular fractionation was obtained from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Blood Bank.

Analysis of P-selectin surface expression

For analysis of P-selectin surface expression from permeabilized platelets,36 20 μL gel-filtered platelets (1 × 108/mL-2 × 108/mL) in 5 mM MgATP was incubated with 3 U/mL reduced SL-O in the presence or absence of the indicated concentration of antihuman cellubrevin antibody. Samples were adjusted to pH 6.9 immediately following permeabilization. After a 20-minute incubation with antibody, CaCl2 was added to the reaction mixture. The amount of CaCl2 required to give a free Ca++ concentration of 10 μM in the presence of 2 mM EGTA at pH 6.9 was calculated as described previously.36Following an additional 10-minute incubation after the addition of Ca++, 10 μL reaction mixture was transferred to 5 μL phycoerythrin-conjugated AC1.2 anti–P-selectin antibody. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 500 μL) was added to the sample after a 20-minute incubation, and the platelets were analyzed immediately by flow cytometry.

Immunonanogold labeling and electron microscopy

Purified human platelets were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.02 M PBS, pH 7.4, for 1 hour at room temperature, washed in 0.02 M PBS, pH 7.4, transferred to microtubes, and centrifuged at 1500g for 1 minute. They were then resuspended in molten 2% agar and quickly recentrifuged. Resultant agar pellets containing the platelets were washed in PBS before immersion in 30% sucrose in 0.02 M PBS, pH 7.4, overnight at 4°C, embedded in OCT compound (Miles, Elkhart, IN), and stored in −176°C liquid nitrogen for subsequent use. Frozen 10-μm sections were cut with a standard cryostat and were collected on precleaned glass slides. These sections were air dried for 20 minutes before staining.

Immunonanogold staining and processing for electron microscopy was performed at room temperature on cryostat sections mounted on glass slides, as follows37: (1) wash in 0.02 M PBS, pH 7.4, 5 minutes; (2) immersion in 50 mM glycine in 0.02 M PBS, pH 7.4, 10 minutes; (3) wash in 0.02 M PBS, pH 7.4, 5 minutes; (4) immersion in 5% normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), 20 minutes; (5) incubation in the primary antibody, an affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody against the 12 N-terminal amino acids of human cellubrevin, at a dilution of 1:30-50, in a rabbit polyclonal antiserum against the C-terminal end of SNAP-23 at a dilution of 1:50, or in an affinity-purified goat polyclonal antibody against the C-terminal end of syntaxin 1A, 1B, 2, and 3 at a dilution of 1:10 in 0.02 M PBS, 60 minutes; (6) 3 washes in 0.02 M PBS, pH 7.4, 5 minutes each; (7) incubation in the secondary antibody (affinity-purified Fab' fragment from goat anti–rabbit IgG conjugated with 1.4 nm nanogold for human cellubrevin and SNAP-23 staining or affinity-purified Fab' fragment from rabbit anti–goat immunoglobulin G (IgG) conjugated with 1.4 nm nanogold for syntaxin staining) (Nanoprobes, Stony Brook, NY), 1:50-100 in 0.02 M PBS, pH 7.4, 60 minutes; (8) 3 washes in 0.02 M PBS, pH 7.4, 5 minutes each; (9) after fixation in 1% glutaraldehyde in 0.02 M PBS, pH 7.4, 2 minutes; (10) 3 washes in distilled water, 5 minutes each; (11) development with highest quality (HQ) silver enhancement solution (Nanoprobes) for 6 to 10 minutes in the darkroom; (12) 2 washes in distilled water, 2 minutes each; (13) immersion in 5% sodium thiosulfate, 1 minute; (14) 3 washes in distilled water, 5 minutes each; (15) after fixation in 1% osmium tetroxide in Sym-Collidine buffer, pH 7.4, 10 minutes; (16) one wash in 0.05 M sodium maleate buffer, pH 5.2, 5 minutes; (17) staining with 2% uranyl acetate in 0.05 M sodium maleate buffer, pH 6.0, 5 minutes; (18) one wash in distilled water, 5 minutes; (19) dehydration in graded ethanols and infiltration with a propylene oxide-eponate (Ted Pella, Redding, CA) sequence; (20) embedment by the inversion of eponate-filled plastic capsules over the slide-attached tissue sections; (21) polymerization at 60°C for 16 hours; (22) separation of eponate blocks from glass slides by brief immersion in liquid nitrogen; (23) cutting of thin sections with a diamond knife with an ultratome (Reichert, Vienna, Austria) and collection of sections on uncoated 200-mesh copper grids (Ted Pella); and (24) viewing of unstained grids with a transmission electron microscope (CM 10; Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands).

The following 5 controls were performed to ensure the specificity of immunostaining: absorption of primary antibody by affinity chromatography to solid-phase human cellubrevin peptide; replacement of primary antibody by an irrelevant rabbit IgG or goat IgG; omission of specific primary antibody; omission of secondary antibody; and omission of HQ silver enhancement solution.

For quantitation, immunogold particles on randomly imaged platelets were counted manually and were assigned to various subcellular membrane compartments that included the α-granule membrane compartment, the OCS membrane compartment, the plasma membrane compartment, and all other membranes as a single compartment. Granular membrane is defined as a trilaminar unit, electron-dense structure enclosing classic α-granule matrix materials. OCS membrane is defined as a trilaminar unit, electron-dense structure enclosing elongated, electron-lucent cytoplasmic canaliculi that permeate the platelet cytoplasm and are open to the plasma membrane by narrow pores. Plasma membrane is defined as a trilaminar electron-dense structure enclosing the platelet cytoplasm in its entirety. Other membranes are defined as all trilaminar unit structures that enclose other platelet organelles (eg, dense tubular system, mitochondria, lysosomes, vesicles, β-granules). The percentage of labeling for each compartment was calculated and is indicated in Table 1.

Immunonanogold localization of SNARE proteins of the platelet exocytotic core complex

| Antibody . | Total particles counted . | Granule membrane, % . | OCS membrane, % . | Plasma membrane, % . | Other membrane, %* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human cellubrevin | 1014 | 80.5 | 9.1 | 4.6 | 5.8 |

| Syntaxin 2 | 1004 | 35.9 | 28.8 | 24.6 | 10.8 |

| SNAP-23 | 1067 | 20.3 | 15.8 | 63.3 | 0.6 |

| Antibody . | Total particles counted . | Granule membrane, % . | OCS membrane, % . | Plasma membrane, % . | Other membrane, %* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human cellubrevin | 1014 | 80.5 | 9.1 | 4.6 | 5.8 |

| Syntaxin 2 | 1004 | 35.9 | 28.8 | 24.6 | 10.8 |

| SNAP-23 | 1067 | 20.3 | 15.8 | 63.3 | 0.6 |

All other platelet organelle membranes.

Subcellular fractionation

Platelet-rich plasma (approximately 1 × 109 platelets/mL) obtained from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Blood Bank was transferred to a Fenwal transfer pack (Baxter, Deerfield, IL) and was incubated with 25 μg/mL sulfo-NHS-biotin (Pierce) at 4°C for 1 hour. Platelets were subsequently washed 3 times with ice-cold buffer P (145 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 10 mM glucose, 25 mM HEPES, 0.5 mM EGTA, 2.5 μM PGE1, 100 μg/mL apyrase, and 100 μM aspirin). Following the final wash, platelets were resuspended in 50 mL ice-cold buffer P and subjected to nitrogen cavitation for 20 minutes at 100 atm on ice, as previously described.38 The cavitate was subsequently processed according to a modification of the procedures described by Gogstad et al.39 40 Briefly, the cavitate was collected and pelleted at 4000g for 20 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 50 mL ice-cold buffer P and was subjected to a second round of cavitation. This cavitate was pelleted at 4000g for 20 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected for analysis. Metrizamide was added to the supernatant of the second cavitation to a final concentration of 11% metrizamide. This material (10 mL) was then loaded onto 2 mL beds of 30% metrizamide. The material was subjected to centrifugation at 40 000g for 2 hours at 4°C. This procedure resulted in a band at the 11% to 30% metrizamide interface that was collected and dialyzed into PBS at 4°C. Metrizamide was added to the dialysate to a final concentration of 11% metrizamide, and 2.5 mL (2 mg/mL protein) was loaded onto 12-mL step gradients consisting of 15%, 20%, 25%, and 30% metrizamide. Step gradients were subjected to centrifugation at 40 000g for 2 hours at 4°C. Following centrifugation, the interfaces of the gradients were collected by fractionation. Protein concentrations of the fractions were determined with a DC Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad) using bovine serum albumin–metrizamide standards. Samples were analyzed by immunoblot analysis using the indicated antibody.

14C-serotonin was used as a marker for platelet-dense granules to evaluate the migration of dense granules in the metrizamide step gradient. In these experiments, 50 μCi (1.85 MBq)14C-serotonin was added to 150 mL platelet-rich plasma for 30 minutes. Platelets were subsequently washed and processed as described above. Following fractionation, 100-μL samples from the step gradient were mixed with 5 mL Aquasol scintillation cocktail (Packard, Meriden, CT). Radioactivity in each sample was then quantified using a Tri-carb 2100TR Liquid Scintillation Analyzer (Packard Instrument, Downers Grove, IL).

Immunoblot analysis

Aliquots of the subcellular fractions were diluted in sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, 0.01% bromophenol blue) at 95°C for 5 minutes. Proteins were then separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Biotin-labeled samples were developed using an avidin-HRP conjugate. Surface labeling is represented by a 65-kd band previously shown to be a dominant protein on the surface of biotin-labeled, resting platelets.41Immunoblotting was performed using anti–P-selectin cytoplasmic tail, CD53, human cellubrevin, SNAP-23, or syntaxin 2 antibodies, as indicated, and was visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence.

Results

Human cellubrevin mediates α-granule secretion

VAMP has previously been shown to mediate platelet α-granule secretion.29 A novel isoform of VAMP, human cellubrevin (VAMP 3), was initially discovered in platelets.33 A function for human cellubrevin in platelet α-granule secretion, however, has not been previously demonstrated. We therefore sought to determine whether this VAMP isoform mediated platelet α-granule secretion. For these experiments, an antipeptide antibody directed against the unique N-terminal portion of human cellubrevin was tested in an SL-O–permeabilized model of platelet α-granule secretion. The antihuman cellubrevin antibody recognized a single band that migrated with an apparent molecular mass of 15 kd in platelet lysate. In addition, the protein recognized by this antibody was sensitive to cleavage by tetanus toxin, consistent with human cellubrevin (Figure 1A). Previous studies have demonstrated that antibodies directed at this peptide fail to recognize VAMP 1 or VAMP 2.33 Consistent with this previous work, the antihuman cellubrevin antibody used in these experiments failed to recognize any VAMP isoforms in brain lysate, which contains predominantly VAMP 1 and VAMP 2,42 and it only recognized a band that migrated with an apparent molecular mass of 15 kd in fibroblast lysate, which contains VAMP 2 and VAMP 343 (Figure 1B). In contrast, an antibody directed at an epitope that is common among VAMP isoforms recognized bands that migrated with an apparent molecular mass of 18 kd in brain and fibroblast lysates and bands that migrated with an apparent molecular mass of 15 kd in fibroblast and platelet lysates (Figure 1B). Thus, the antihuman cellubrevin used in these studies does not recognize VAMP 1 or VAMP 2.

Characterization of the antihuman cellubrevin antibody.

(A) Gel-filtered platelets (50 μL) were permeabilized with 4 U/mL SL-O in the presence of reducing buffer (no addition) or 2 μM tetanus toxin in reducing buffer (tetanus toxin) for 45 minutes. Platelet proteins were subsequently solubilized in sample buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to a polyvinylidene (PVDF) membrane. Human cellubrevin was visualized by immunoblotting using the antihuman cellubrevin antibody. (B) Proteins from bovine brain, human fibroblasts, and human platelets were solubilized, separated by SDS-PAGE on 15% acrylamide gels, and transferred to PVDF membranes. Lysates were equalized for total protein, and immunoblotting was performed using either the antihuman cellubrevin antibody or an antibody directed against an epitope common to VAMP 1, VAMP 2, and human cellubrevin.

Characterization of the antihuman cellubrevin antibody.

(A) Gel-filtered platelets (50 μL) were permeabilized with 4 U/mL SL-O in the presence of reducing buffer (no addition) or 2 μM tetanus toxin in reducing buffer (tetanus toxin) for 45 minutes. Platelet proteins were subsequently solubilized in sample buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to a polyvinylidene (PVDF) membrane. Human cellubrevin was visualized by immunoblotting using the antihuman cellubrevin antibody. (B) Proteins from bovine brain, human fibroblasts, and human platelets were solubilized, separated by SDS-PAGE on 15% acrylamide gels, and transferred to PVDF membranes. Lysates were equalized for total protein, and immunoblotting was performed using either the antihuman cellubrevin antibody or an antibody directed against an epitope common to VAMP 1, VAMP 2, and human cellubrevin.

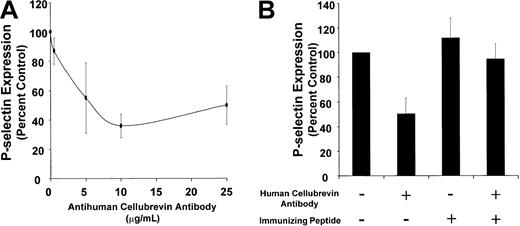

We next tested the activity of this antibody in a Ca++-triggered, SL-O–permeabilized platelet model of α-granule secretion. P-selectin surface expression was monitored to assess α-granule secretion. Purified antihuman cellubrevin antibody inhibited P-selectin surface expression with maximal inhibition of approximately 50% (Figure 2A). In contrast, incubation of SL-O–permeabilized platelets with 25 μg/mL nonimmune rabbit IgG resulted in 122% ± 24% expression of P-selectin surface expression when compared with SL-O–permeabilized platelets exposed to buffer alone. Inhibition of P-selectin surface expression reversed on preincubation of the antibody with a 5-molar excess of the immunizing peptide (P ≤ .001) (Figure 2B). Thus, human cellubrevin participates in Ca++-induced α-granule secretion in the SL-O–permeabilized platelet system.

Effect of antihuman cellubrevin antibody on Ca++-induced P-selectin surface expression in SL-O–permeabilized platelets.

(A) Gel-filtered platelets (20 μL/sample) in PIPES/EGTA buffer supplemented with 5 mM MgATP were permeabilized with 3 U/mL SL-O in the presence or absence of the indicated concentration of antihuman cellubrevin antibody at pH 6.9 for 20 minutes. Platelets were then exposed to 10 μM Ca++ for 10 minutes. P-selectin surface expression was assayed by incubating the sample (10 μL) with a phycoerythrin-conjugated AC1.2 anti–P-selectin antibody (5 μL) for 20 minutes. PBS (500 μL) was added to the sample, and the platelets were analyzed immediately by flow cytometry. Data are expressed as the percentage inhibition of P-selectin expression in samples exposed to anticellubrevin antibody compared with samples exposed to buffer alone. Error bars represent the SE of 3 to 6 independent experiments. (B) Gel-filtered platelets in PIPES/EGTA buffer supplemented with 5 mM MgCl2 were preincubated with either no addition or 1 μg/mL human cellubrevin peptide in the presence or absence of 25 μg/mL antihuman cellubrevin antibody, as indicated. Platelets were then permeabilized with 3 U/mL SL-O at pH 6.9 for 20 minutes and were subsequently exposed to buffer or 10 μM Ca++ for 10 minutes. Platelets were assayed for P-selectin expression by flow cytometry. Error bars represent the SE of 3 to 6 independent experiments.

Effect of antihuman cellubrevin antibody on Ca++-induced P-selectin surface expression in SL-O–permeabilized platelets.

(A) Gel-filtered platelets (20 μL/sample) in PIPES/EGTA buffer supplemented with 5 mM MgATP were permeabilized with 3 U/mL SL-O in the presence or absence of the indicated concentration of antihuman cellubrevin antibody at pH 6.9 for 20 minutes. Platelets were then exposed to 10 μM Ca++ for 10 minutes. P-selectin surface expression was assayed by incubating the sample (10 μL) with a phycoerythrin-conjugated AC1.2 anti–P-selectin antibody (5 μL) for 20 minutes. PBS (500 μL) was added to the sample, and the platelets were analyzed immediately by flow cytometry. Data are expressed as the percentage inhibition of P-selectin expression in samples exposed to anticellubrevin antibody compared with samples exposed to buffer alone. Error bars represent the SE of 3 to 6 independent experiments. (B) Gel-filtered platelets in PIPES/EGTA buffer supplemented with 5 mM MgCl2 were preincubated with either no addition or 1 μg/mL human cellubrevin peptide in the presence or absence of 25 μg/mL antihuman cellubrevin antibody, as indicated. Platelets were then permeabilized with 3 U/mL SL-O at pH 6.9 for 20 minutes and were subsequently exposed to buffer or 10 μM Ca++ for 10 minutes. Platelets were assayed for P-selectin expression by flow cytometry. Error bars represent the SE of 3 to 6 independent experiments.

Subcellular localization of human cellubrevin in platelets

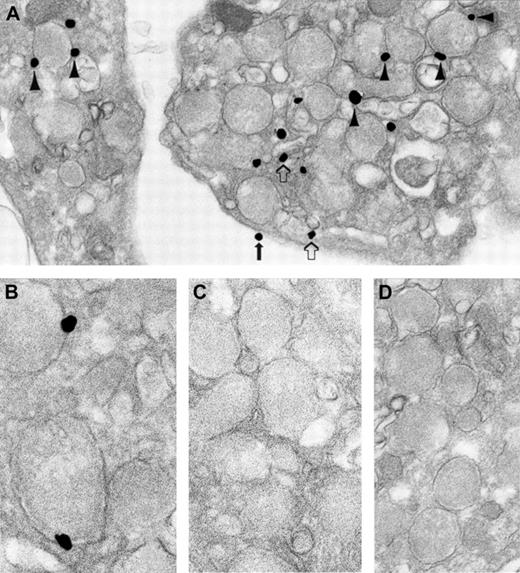

Given that human cellubrevin participates in α-granule secretion, we sought to determine the subcellular localization of this VAMP isoform. A pre-embedding immunonanogold staining technique with analysis by transmission electron microscopy was used in these studies because this technique can reliably distinguish among the various membrane compartments of platelets. Immunolocalization demonstrated that most human cellubrevin is associated with granule membranes (Figure 3A-B). A small amount of human cellubrevin was found associated with the OCS and the plasma membrane compartments. Although the amount of human cellubrevin associated with the OCS and the plasma membrane compartments amounted to less than 15% of the total, human cellubrevin staining of these membrane compartments was consistently observed in randomly selected, resting platelets. The amount of human cellubrevin associated with the platelet plasma membrane was less than that associated with the OCS (Table 1). Control samples processed with either substitution of irrelevant rabbit IgG for immune primary antibody (Figure 3D) or omission of immune primary antibody demonstrated no significant staining. Samples processed with immune antibody subjected to affinity chromatography to solid-phase human cellubrevin peptide also showed no significant staining (Figure 3C). Similarly, no significant staining was observed when the secondary antibody or the HQ silver enhancement solution was omitted from the processing. Additionally, staining was virtually absent in the α-granule matrix and in the mitochondria.

Ultrastructural immunonanogold localization of human cellubrevin in unstimulated human platelets.

Most silver-enhanced gold particles are attached to α-granule membranes (A, arrowheads; B). Label is also present on OCS (A, open arrows) and plasma membrane (A, solid arrow). (C) Absorption control of the specific primary antibody with cellubrevin is negative. (D) Irrelevant rabbit IgG was substituted for the specific primary antibody, and no labeling is seen. Original magnifications: A, × 42 000; B, × 86 000; C, × 56 000; D, × 48 000.

Ultrastructural immunonanogold localization of human cellubrevin in unstimulated human platelets.

Most silver-enhanced gold particles are attached to α-granule membranes (A, arrowheads; B). Label is also present on OCS (A, open arrows) and plasma membrane (A, solid arrow). (C) Absorption control of the specific primary antibody with cellubrevin is negative. (D) Irrelevant rabbit IgG was substituted for the specific primary antibody, and no labeling is seen. Original magnifications: A, × 42 000; B, × 86 000; C, × 56 000; D, × 48 000.

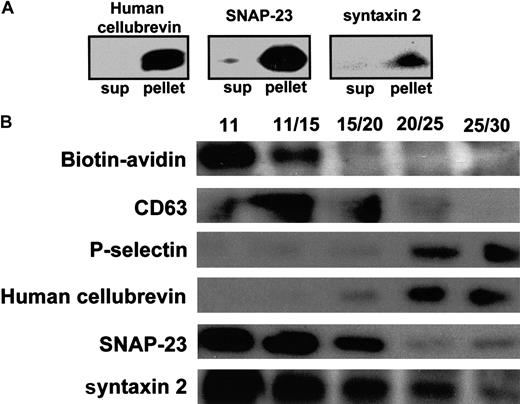

To determine the relative distribution of SNARE proteins in platelets by an independent method, subcellular fractionation was performed. Although this technique cannot separate OCS from plasma membranes, subcellular fractionation is capable of separating OCS and plasma membranes from α-granules. More than 97% of the SNARE protein content of the platelet cavitate that was used for subcellular fractionation was found in the pellet following ultracentrifugation (Figure 4A). This result demonstrated that the 3 SNARE proteins analyzed in these studies are membrane-bound. To detect the OCS and plasma membranes in fractions of the step gradient, platelets were surface labeled using NHS-biotin at 4°C.41 An advantage of using biotin to label platelet OCS and plasma membrane proteins is that it is able to enter the pores of the OCS and to label proteins of the OCS and the plasma membranes.44 P-selectin served as a marker for platelet α-granule membranes because it is a transmembrane protein that resides exclusively in the α-granule of the resting platelet.45 A soluble marker of α-granules, β-thromboglobulin comigrated with P-selectin (data not shown), demonstrating that P-selectin migrated with intact α-granules. Because functional studies suggest that platelet dense granules46 and platelet lysosomes47demonstrate SNARE proteins on their cytoplasmic surfaces, we evaluated the migration of these platelet granules in our subcellular fractionation experiments. 14C-serotonin was used to label platelet-dense granules. CD63 was used as a marker for lysosomes.

Localization of human cellubrevin, SNAP-23, and syntaxin 2 by immunoblot analysis of subcellular fractions.

(A) Platelet cavitate was prepared as described in “Materials and methods,” and the fraction recovered from the 11% to 30% metrizamide interface was subjected to centrifugation at 100 000g for 1 hour. Supernatants and pellets were separated. Supernatants (sup) were subsequently lyophilized and solubilized in sample buffer. Proteins in the lyophilized supernatants and pellets were separated by SDS-PAGE and were analyzed for human cellubrevin, SNAP-23, and syntaxin 2 by immunoblotting with antihuman cellubrevin antibody, anti–SNAP-23 antibody, or antisyntaxin antibody, as indicated. (B) Platelet cavitate was prepared from biotin-labeled platelets and separated in a density step gradient of 11%, 15%, 20%, 25%, and 30% metrizamide. Fractions were analyzed using an avidin-HRP conjugate or by immunoblotting with anti-CD63 antibody, anti–P-selectin antibody, antihuman cellubrevin antibody, anti–SNAP-23 antibody, or antisyntaxin 2 antibody, as indicated.

Localization of human cellubrevin, SNAP-23, and syntaxin 2 by immunoblot analysis of subcellular fractions.

(A) Platelet cavitate was prepared as described in “Materials and methods,” and the fraction recovered from the 11% to 30% metrizamide interface was subjected to centrifugation at 100 000g for 1 hour. Supernatants and pellets were separated. Supernatants (sup) were subsequently lyophilized and solubilized in sample buffer. Proteins in the lyophilized supernatants and pellets were separated by SDS-PAGE and were analyzed for human cellubrevin, SNAP-23, and syntaxin 2 by immunoblotting with antihuman cellubrevin antibody, anti–SNAP-23 antibody, or antisyntaxin antibody, as indicated. (B) Platelet cavitate was prepared from biotin-labeled platelets and separated in a density step gradient of 11%, 15%, 20%, 25%, and 30% metrizamide. Fractions were analyzed using an avidin-HRP conjugate or by immunoblotting with anti-CD63 antibody, anti–P-selectin antibody, antihuman cellubrevin antibody, anti–SNAP-23 antibody, or antisyntaxin 2 antibody, as indicated.

Analysis of the nitrogen cavitate of biotin-labeled platelets demonstrates complete separation of biotin-labeled membranes from P-selectin–containing fractions (Figure 4B). OCS and plasma membranes were recovered primarily in the 11% fraction and the 11% to 15% interface, whereas α-granules were recovered primarily in the 20% to 25% and the 25% to 30% metrizamide interfaces, consistent with previously reported platelet fractionation results.48 CD63 is localized primarily to the 11% to 15% and the 15% to 20% metrizamide interfaces. A small amount of CD63, however, was observed in the 20% to 25% metrizamide interface. Subcellular fractionation performed using platelets labeled with 14C-serotonin demonstrated that less than 1.5% of the 14C-serotonin loaded on step gradients was observed in the 20% to 25% metrizamide interface and that less than 3.0% was observed in the 25% to 30% metrizamide interface. Thus, dense granules were not a substantial constituent of the α-granule–containing fractions. Most14C-serotonin was found within the 30% metrizamide fraction and in the pellet. These results are consistent with previous subcellular localization studies using 14C-serotonin as a marker for platelet-dense granules.39 40 These observations suggest that SNARE proteins detected in the 25% to 30% interface are associated with α-granules. When fractions from the step gradient were stained for human cellubrevin, antigen was found primarily at the 20% to 25% and 25% to 30% metrizamide interfaces. Thus, human cellubrevin is found primarily in α-granule–enriched fractions (Figure 4). This observation is consistent with the findings of ultrastructure studies demonstrating that human cellubrevin is localized primarily in α-granule membranes (Figure 3).

Subcellular localization of SNAP-23 in platelets

SNAP-23 is the SNAP isoform demonstrated to function in platelet α-granule release.34 Pre-embedding immunonanogold ultrastructural studies were performed to define the subcellular distribution of SNAP-23 in platelets. These studies demonstrated that this SNARE protein is predominantly associated with OCS and plasma membranes (Figure 5A-C). Furthermore, 4-fold more SNAP-23 was associated with plasma membrane than with OCS (Table 1). The amount of SNAP-23 associated with the granule membrane was similar to the amount associated with the OCS. Control samples processed with the substitution of irrelevant rabbit IgG for immune primary antibody (Figure 5D) or the omission of immune primary antibody demonstrated no significant staining. Similarly, no significant staining was observed when either the secondary antibody or the HQ silver enhancement solution was omitted from the processing. Additionally, staining was virtually absent over the α-granule matrix and over the mitochondria. Localization of SNAP-23 by subcellular fractionation demonstrated that most of this SNARE protein comigrated with biotin-labeled membranes (Figure 4). This observation is consistent with the immunonanogold staining that shows most SNAP-23 is associated with OCS and plasma membranes. A fraction of SNAP-23, however, was consistently found in the 25% to 30% interface, as was observed with the antihuman cellubrevin antibody. These observations demonstrate that SNAP-23 is present in the α-granule–enriched fractions of the step gradient, which concurs with the ultrastructure study findings and suggests that some SNAP-23 is present on platelet α-granules.

Ultrastructural immunonanogold localization of SNAP-23 in unstimulated human platelets.

(A) Most silver-enhanced gold particles are bound to the plasma membrane (arrows). Some are also observed on membranes of the OCS (open arrows) and on α-granule membranes (arrowheads). Mitochondria (M) are not labeled. (B) Two labeled α-granule membranes are shown at higher magnification. (C) Labeled OCS membrane. (D) Negative control in which the specific primary antibody was replaced by an irrelevant rabbit IgG. Original magnifications: A, × 42 000; B, × 86 000; C, × 70 000; D, × 38 000.

Ultrastructural immunonanogold localization of SNAP-23 in unstimulated human platelets.

(A) Most silver-enhanced gold particles are bound to the plasma membrane (arrows). Some are also observed on membranes of the OCS (open arrows) and on α-granule membranes (arrowheads). Mitochondria (M) are not labeled. (B) Two labeled α-granule membranes are shown at higher magnification. (C) Labeled OCS membrane. (D) Negative control in which the specific primary antibody was replaced by an irrelevant rabbit IgG. Original magnifications: A, × 42 000; B, × 86 000; C, × 70 000; D, × 38 000.

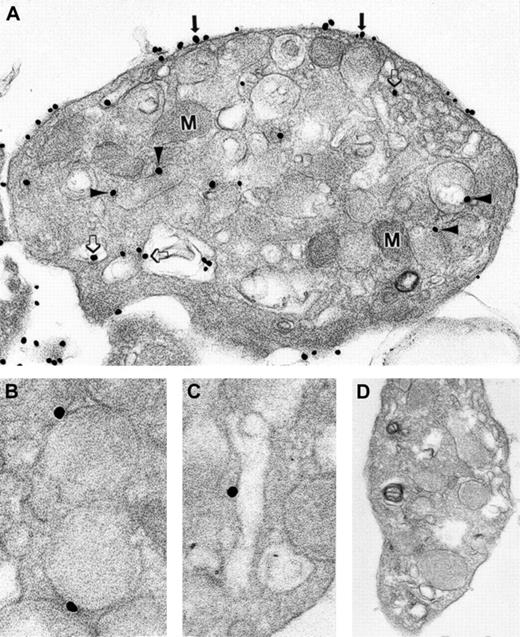

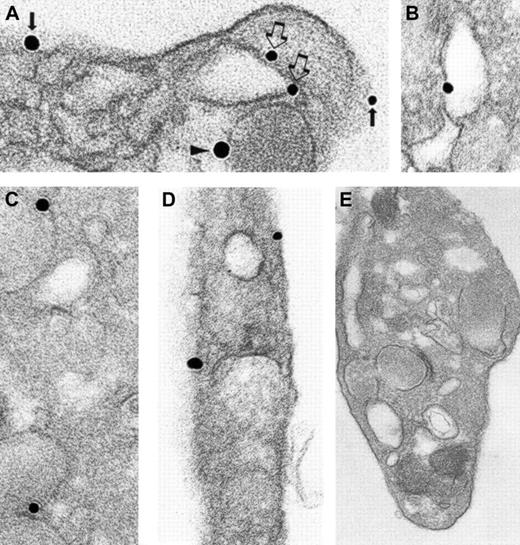

Subcellular localization of syntaxin 2

Syntaxin 2 has been shown to mediate α-granule secretion34 along with syntaxin 4.29 34Therefore, we sought to determine the subcellular localization of this member of the platelet trimeric exocytotic complex. Immunonanogold ultrastructural studies demonstrated that syntaxin 2 was found on OCS, plasma, and granule membranes (Figure6A-D; Table 1). Syntaxin 2 was localized more evenly than human cellubrevin or SNAP-23 among these 3 membrane compartments. Control samples processed with the substitution of irrelevant goat IgG (Figure 6E) for immune primary antibody or the omission of immune primary antibody demonstrated no significant staining. In addition, no significant staining was observed when the secondary antibody or the HQ silver enhancement solution was omitted from the processing. As with the other antibodies, staining was virtually absent in the α-granule matrix and in the mitochondria. Immunoblot analysis of subcellular fractions from the step gradient demonstrated that syntaxin 2 comigrates with biotin-labeled fractions and with fractions containing P-selectin (Figure 4). This pattern of staining suggests that syntaxin 2 is present on OCS and plasma membranes and on α-granules. Thus, antihuman cellubrevin, anti–SNAP-23, and anti–syntaxin 2 antibodies all react with an antigen in the α-granule–enriched fractions. Consistent with the immunonanogold staining, this observation suggests that all 3 SNARE proteins of the trimeric exocytotic complex are present on platelet α-granules.

Ultrastructural immunonanogold localization of syntaxin 2 in unstimulated human platelets.

(A) α-Granule (arrowhead), OCS (open arrows), and plasma membranes (solid arrows) are labeled. Another OCS membrane (B), several α-granule membranes (C), and plasma membrane (D) labeled with silver-enhanced gold particles are shown. (E) Specific primary antibody was replaced by an irrelevant goat IgG. No gold particles are present. Original magnifications: A, × 86 000; B, × 77 000; C, × 70 000; D, × 83 000; E, × 42 000.

Ultrastructural immunonanogold localization of syntaxin 2 in unstimulated human platelets.

(A) α-Granule (arrowhead), OCS (open arrows), and plasma membranes (solid arrows) are labeled. Another OCS membrane (B), several α-granule membranes (C), and plasma membrane (D) labeled with silver-enhanced gold particles are shown. (E) Specific primary antibody was replaced by an irrelevant goat IgG. No gold particles are present. Original magnifications: A, × 86 000; B, × 77 000; C, × 70 000; D, × 83 000; E, × 42 000.

Discussion

With respect to regulated vesicle exocytosis, the original SNARE hypothesis predicted that vSNAREs located on vesicles interact with tSNAREs located on plasma membranes. Detailed subcellular localization of SNARE proteins in synaptosomal preparations and yeast, however, have demonstrated that the assignment of tSNAREs to plasma membrane and vSNAREs to vesicle membranes cannot be generalized. Immunogold labeling of synaptosomal preparations demonstrated that syntaxin and SNAP-25 colocalize on vesicles.49 In fact, syntaxin 1 and SNAP-25 comprise 3% of the total protein of purified synaptic vesicles.50 A ternary cis complex of syntaxin, SNAP-25, and VAMP has been demonstrated to assemble and disassemble on purified synaptic vesicles in the absence of plasma membrane.51 In yeast, isolated vacuoles were also found to contain tSNAREs and vSNAREs, which were demonstrated to form a pentameric cis complex required for membrane fusion.52 Subcellular localization of SNARE proteins has also been performed in some hematopoietic cells. In neutrophils, VAMP-2 was concentrated in tertiary granules and secretory vesicles, whereas syntaxin 4 was found almost exclusively in plasma membrane.53 In resting mast cells, subcellular fractionation showed that VAMP 2 and syntaxin 3 were associated with granules, whereas syntaxin 4 and SNAP-23 were absent from the granules.54 Ultrastructural studies showed that on activation, SNAP-23 relocated from plasma membrane lamellipodialike projections to mast cell granule membranes.

To better understand the molecular basis for the unusual morphologic features of the platelet-release reaction, we determined the subcellular localization of 3 functional SNARE proteins of the trimeric exocytotic complex. SNAP-23 and syntaxin 2 have been demonstrated to function in platelet granule secretion.29,32,34 Given that a function for human cellubrevin in platelet granule secretion had not previously been demonstrated, we sought to determine whether this vSNARE contributed to granule secretion before we performed subcellular localization of this VAMP isoform. Antibody directed at human cellubrevin inhibited Ca++-induced α-granule secretion from SL-O–permeabilized platelets with a maximum inhibition of approximately 50%. We have previously demonstrated that an antibody directed at a coiled-coil region common among VAMP isoforms inhibited Ca++-induced α-granule secretion by approximately 95%.29 One possible explanation for the discrepancy between these results is that VAMP isoforms other than human cellubrevin also participate in α-granule secretion. A second possible explanation is that because the antihuman cellubrevin antibody is directed at an N-terminal region that is not likely to directly bind tSNAREs, it may not be as effective in inhibiting SNARE protein interactions as the antibody directed at the coiled-coil domain of VAMP isoforms. In either case, we can conclude from these functional studies that human cellubrevin functions in Ca++-induced platelet granule secretion.

Immunonanogold staining and subcellular fractionation demonstrate human cellubrevin, SNAP-23, and syntaxin 2 on platelet granule membranes. It is possible that trans complexes of vSNAREs and tSNAREs exist between granules facilitating homotypic granule fusion. An alternative possibility is that these 3 SNARE proteins exist in acis complex on isolated granules in the resting platelet, as has been found in neurons and yeast.51 52 In this scenario, activation of the platelet may lead to the disassembly ofcis complexes and the formation of transcomplexes that drive homotypic granule fusion. In either case, the observation that platelet granules contain vSNAREs and tSNAREs forms a molecular basis for homotypic granule fusion. Similarly, the distribution of functional SNARE proteins of the trimeric exocytotic complex provides a molecular mechanism whereby platelet granules can fuse with the plasma membrane and membranes of the OCS. Although the composition of SNARE proteins, as detected by immunonanogold electron microscopic labeling, differs between OCS and plasma membranes (Table1), both membranes are relatively enriched for tSNAREs that could interact with vSNARE isoforms, such as human cellubrevin, on granule membranes.

One important observation regarding the subcellular localization of human cellubrevin, SNAP-23, and syntaxin 2 is that SNARE protein distribution in an anucleate system is not random. The quantitation of immunogold labeling of human cellubrevin and SNAP-23 demonstrates that each functional SNARE protein of the trimeric exocytotic complex has a distinct localization (Table 1). A study by Chen et al47performed in platelets using a postembedding labeling technique demonstrated that syntaxins 2 and 4 associate with granule membranes and with OCS and plasma membranes. Consistent with their results, our study found that the largest portion of syntaxin 2 associates with granule membranes and that the remainder is divided evenly between OCS and plasma membranes. Human cellubrevin is found predominantly in granule membranes. Of the human cellubrevin not associated with granule membranes, approximately twice as much is present in OCS as in plasma membranes. This pattern of distribution differs in several respects from that of SNAP-23. Not only is SNAP-23 found predominantly (approximately 80%) on OCS and plasma membranes, but labeling reveals 4 times more SNAP-23 staining of plasma membranes than of the membranes of the OCS. Thus, SNARE protein staining of platelet granular membranes, OCS, and plasma membranes demonstrates a distinct pattern of distribution for each membrane compartment.

Subcellular fractionation confirms a nonrandom distribution of SNARE proteins of the exocytotic complex in platelets. The abundance of SNAP-23 and syntaxin 2 detected in fractions that migrate with OCS and plasma membranes may be secondary to the fact that the subcellular fractionation strategy described in these studies demonstrates a 2- to 3-fold better yield for biotin-labeled membranes (ie, OCS and plasma membranes) than for P-selectin– and β-thromboglobulin–containing membranes (ie, α-granule membranes). Subcellular fractionation demonstrates that human cellubrevin is recovered predominantly in fractions that include P-selectin–containing granules. The fact that no human cellubrevin colocalizes with biotin label is likely secondary to the fact that the small amount of human cellubrevin detected on OSC and plasma membrane by immunonanogold localization is below the detection level of the immunoblotting of subcellular fractions. SNAP-23 and syntaxin 2 also comigrate with P-selectin–containing granules. The observation that 3 functional SNARE proteins of the trimeric exocytotic complex comigrate in the 20% to 25% and the 25% to 30% metrizamide interfaces concurs with the findings of ultrastructure studies and suggests that resting platelet α-granule membranes contain trimeric exocytotic complexes. This possibility is consistent with our previous observation that an approximately 70-kd complex including a VAMP isoform, SNAP-23, and syntaxin 4 exists in resting platelets.29 These observations are also consistent with those of Reed et al,31 which demonstrated that a syntaxin 4 antibody coimmunoprecipitated the 2 other members of the platelet trimeric exocytotic complex. Preliminary studies demonstrate a trimeric exocytotic complex in the 25% to 30% metrizamide interface that contains purified α-granule membranes (data not shown). Future studies will determine whether such complexes exist in a cisor a trans confirmation and under what conditions such complexes disassociate.

One explanation for the nonrandom nature of SNARE protein distribution in platelets is that SNARE proteins are targeted differentially to platelet membranes during megakaryocytopoiesis and that this distribution is maintained throughout the lifespan of the platelet. This mechanism alone would require that little membrane trafficking occur in the platelet because rapid membrane turnover would lead to membrane mixing and uniformity of SNARE protein distribution. However, constitutive endocytosis1,3,55 and true phagocytosis56,57 have been reported in platelets. In most cells, endocytosis is accompanied by exocytosis to maintain a relatively constant plasma membrane surface area. For example, the surface area of the monocyte remains relatively stable despite the fact that it ingests 3% of its plasma membrane every minute.58Even if membrane turnover is an order of magnitude less robust in platelets, substantial membrane mixing would occur over the lifespan of the platelet. An alternative explanation for the nonrandom distribution of SNARE proteins in the platelet is the possibility that platelets have an active sorting mechanism that, for example, preferentially shuffles human cellubrevin to granule membranes and SNAP-23 to plasma membranes. Delivery of soluble proteins to specific platelet granules and sorting of membrane receptors to specific membrane compartments is well documented in platelets.55,59 The molecular mechanisms directing these constitutive sorting events, however, are ill defined. Studies in nucleated cells have demonstrated that SNARE proteins are involved in constitutive membrane targeting.60,61 In addition, SNARE proteins in nucleated cells recycle between membrane compartments.62 63Constitutive recycling of SNARE proteins may also occur in platelets. This SNARE protein trafficking may contribute to the constitutive membrane and protein sorting observed in platelets.

We thank Kathyrn Pyne for photographic assistance. We thank members of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Blood Bank for their assistance.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI33372 (A.M.D.), AI44066 (A.M.D.), and HL63250 (R.F.). R.F. is a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Awardee and is a participant in the Clinical Investigator Training Program: Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center—Harvard/MIT Health Sciences and Technology, in collaboration with Pfizer Inc.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Robert Flaumenhaft, Department of Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, RE 319, Research East, PO Box 15732, Boston, MA 02215; e-mail:rflaumen@caregroup.harvard.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal