Abstract

In vivo ablation of malignant B cells can be achieved using antibodies directed against the CD20 antigen. Fine specificity differences among CD20 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are assumed not to be a factor in determining their efficacy because evidence from antibody-blocking studies indicates limited epitope diversity with only 2 overlapping extracellular CD20 epitopes. However, in this report a high degree of heterogeneity among antihuman CD20 mAbs is demonstrated. Mutation of alanine and proline at positions 170 and 172 (AxP) (single-letter amino acid codes; x indicates the identical amino acid at the same position in the murine and human CD20 sequences) in human CD20 abrogated the binding of all CD20 mAbs tested. Introduction of AxP into the equivalent positions in the murine sequence, which is not otherwise recognized by antihuman CD20 mAbs, fully reconstituted the epitope recognized by B1, the prototypic anti-CD20 mAb. 2H7, a mAb previously thought to recognize the same epitope as B1, did not recognize the murine AxP mutant. Reconstitution of the 2H7 epitope was achieved with additional mutations replacing VDxxD in the murine sequence for INxxN (positions 162-166 in the human sequence). The integrity of the 2H7 epitope, unlike that of B1, further depends on the maintenance of CD20 in an oligomeric complex. The majority of 16 antihuman CD20 mAbs tested, including rituximab, bound to murine CD20 containing the AxP mutations. Heterogeneity in the fine specificity of these antibodies was indicated by marked differences in their ability to induce homotypic cellular aggregation and translocation of CD20 to a detergent-insoluble membrane compartment previously identified as lipid rafts.

Introduction

CD20, a nonglycosylated 33- to 35-kd integral membrane protein expressed at high density only on B lymphocytes, has proven to be an effective target for immunotherapeutic removal of malignant B cells. Rituximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody (mAb) directed against CD20, is an approved treatment for low-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma (for a review, see Gopal and Press1). Mechanisms involved in anti–CD20-mediated B-cell depletion include complement-mediated lysis and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, but apoptotic cell death occurring as a result of signaling events induced by CD20 cross-linking is also believed to play a role.2-4 It is generally assumed, based on antibody blocking studies,5 that CD20 bears only 2 extracellular epitopes, one that is recognized by the vast majority of CD20 mAbs, and a second that is recognized by a single antibody (1F5) with unusual activating properties. Consequently, little attention has been given to the possibility that heterogeneity in the fine specificity of anti-CD20 mAbs could result in differences in signal initiation, potentially modulating clinical outcome.

The complementary DNA (cDNA) sequence of CD20 predicts a tetraspan protein with intracellular termini and a single extracellular loop between the third and fourth transmembrane domains.6-8 The membrane orientation and topology of CD20 was confirmed using antisera generated against peptides near the amino and carboxyl termini and by proteolytic digestion of extracellular regions.9CD20 forms oligomers on the cell surface, as indicated by chemical cross-linking studies,10 and appears to function as a component or regulator of a voltage-independent calcium channel.10 11

CD20-directed mAbs exert a variety of biochemical and biologic effects on B cells, including activation of tyrosine kinases leading to c-myc induction and homotypic aggregation,12,13 translocation of CD20 to lipid rafts,9,14 down-regulation of antigen and CD23 receptors,15,16 inhibition of antibody production by mitogen-activated B cells,17,18 and induction of apoptosis.2-4,19,20 With the exception of the 1F5 mAb, which appears to be unique in its ability to activate resting B cells,21-25 there have been few indications that CD20 mAbs differ in their effects on B cells. However, we observed differences between 2 mAbs, B1 and 2H7, in their ability to induce intracellular calcium release,13 raft association of CD2014homotypic aggregation of B cells (unpublished data, December 1997), and coprecipitate src family kinases,13,26suggesting that these antibodies recognize distinct epitopes. We therefore sought to characterize CD20 epitopes in greater detail as a means of increasing our understanding of CD20 structure and function. Because antibodies directed against extracellular epitopes on human CD20 do not bind to murine B cells, we took advantage of differences in the amino acid sequences of the extracellular domains of human and mouse CD206-8 27 in a homolog scanning mutagenesis strategy to characterize the fine specificity of CD20 mAbs.

Materials and methods

Cells and antibodies

Raji and Ramos lymphoblastoid B cells were grown in RPMI/5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and HEK293 cells in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM)/10% FBS. 1F5 and 2H7 mAbs were provided by Dr J. Ledbetter, and NK1 by Dr A. Hekman.28 B1 mAb was purchased from Coulter (Miami, FL), L27 from Becton Dickinson (San Jose, CA) and rituximab from IDEC Pharmaceuticals (San Francisco, CA). Other CD20 mAbs were obtained from the human leukocyte differentiation workshops IV, VI, and VII. Affinity-purified rabbit antiserum directed against a peptide near the amino terminus of CD20 (anti-CD20N) was previously described.9 Human IgG and murine isotype control antibodies IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b were purchased from Caltag Laboratories (Burlingame, CA), Sigma (St Louis, MO), and Southern Biotechnology Association (Birmingham, AL). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat antimouse IgG and goat antihuman IgG were from Southern Biotechnology Association and Caltag Laboratories, respectively.

Mutagenesis

Mutations were made using overlap extension polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using human CD20 cDNA template,7 internal primer pairs encoding the desired mutations, and outside primers 5′-ATAATGAATTCATTGAGCCTCTTT-3′ and 5′-AATCACTTAAGGAGAGCT-3′ encoding unique EcoRI and AflII restriction sites at positions 451 and 983, respectively, of the CD20 cDNA. PCR fragments were digested with EcoRI and AflII and cloned into pBluescript containing human CD20 cDNA from which theEcoRI/AflII fragment had been excised. To generate a chimera containing the extracellular sequence of murine CD20 with the transmembrane and intracellular regions of human CD20 (h/m CD20), the extracellular region of human CD20 cDNA was converted to murine using overlap extension PCR. The h/m chimera cDNA was then used as a template to introduce mutations into the murine sequence, generating constructs A through D described in “Results.” Construct C was subsequently used as a template to generate construct E, and construct E was the template for constructs F and G. The sequences of all constructs were confirmed prior to subcloning into the pCDM8 mammalian expression vector.

Transfections

HEK293 cells grown to approximately 50% confluence were transiently transfected with CD20 wild-type and mutant cDNA constructs using the calcium phosphate method. DNA in a 250-mM solution of CaCl2 was slowly bubbled into an equal volume of 2 times Hepes buffer (280 mM NaCl, 50 mM Hepes, 1.5 mM Na2HPO4) and left for no more than 5 minutes to precipitate before transferring to a HEK293 culture plate. Transfection conditions were optimized by monitoring the expression of titrated amounts of CD20 wild-type cDNA construct at 1, 2, 3, and 4 days after transfection. Maximal expression was observed after 2 to 3 days using 10 μg DNA. No difference in expression was observed using 10, 20, or 30 μg cDNA, but to minimize expression variability between samples, we routinely used 20 μg cDNA per sample. Two to 3 days after transfection, cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4), and lifted off the culture plates for analysis of CD20 expression and antibody binding.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were incubated with anti-CD20 or control mAbs in PBS/2% FBS. After washing, bound antibodies were detected using appropriate FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies. As a component of the epitope mapping studies, 1F5, 2H7, and B1 mAbs (1 μg) were preincubated with 10 μg peptide containing a stretch of the least conserved amino acids in the extracellular domain (residues 142-151; ESLNFIRAHT; single-letter amino acid codes), for 30 minutes. Immunofluorescence was measured using a FACScan cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

Biochemical analyses

Cells were washed, pelleted, and lysed on ice for 15 minutes in lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors (1 μg/mL aprotinin, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 mM NaMoO4, 1 mM NaVO4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 1 mM EDTA) and either 1% Triton X-100 or 1% digitonin as indicated. Lysates were cleared of nuclei and other insoluble material by centrifugation at 13 000g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Where indicated, residual detergent-insoluble material was cleared using a Beckman TL-100 ultracentrifuge at 100 000g for 1 hour at 4°C. For immunoprecipitations, lysates were incubated with appropriate antibodies and then with protein A Sepharose (Repligen, Cambridge, MA) for 1 to 2 hours at 4°C. The beads were washed with lysis buffer and precipitated protein was eluted in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer.

CD20 translocation experiments were performed as described.14 Briefly, cells were treated before lysis with anti-CD20 mAbs for 15 minutes at 37°C and both the cleared lysates and the insoluble pellets were collected for analysis by CD20 immunoblotting. Equal cell equivalents from the lysate and pellet samples were loaded onto gels and the relative amount of insoluble CD20 in each sample was estimated and scored as follows: 75% to 100%, ++++; 50% to 75%, +++; 25% to 50%, ++; 5% to 25%, +; and less than 5%, −.

For density gradient centrifugation analysis, 100 mM iodoacetamide (Sigma) was included in the lysed samples to prevent postlysis disulfide bond formation. Cleared lysates were layered onto a 5% to 40% sucrose gradient containing either 1% Triton X-100 or 1% digitonin, as appropriate, and centrifuged at 170 000g for 17 hours at 4°C using a SW41 rotor (Beckman). Fractions (0.5 mL) were collected from the top of the gradients. Protein molecular weight standards (Sigma), run simultaneously on an adjacent gradient, were treated similarly. Equal aliquots of each fraction were mixed with SDS sample buffer. Western blot analysis and Coomassie staining were used to identify the fractions containing CD20 and the molecular weight standards, respectively.

To confirm cell surface expression of constructs transiently expressed in HEK293 cells, proteinase K digests were performed as described.9 Briefly, cells were incubated alone or with 12.5 μM proteinase K for 15 minutes on ice. Protease inhibitors (4 mM Pefabloc [Boehringer Mannheim, Laval, Quebec, Canada], 1 μg/μL aprotinin, 1 μg/μL leupeptin, and 1 mM PMSF) were added to halt digestion. Samples were rapidly centrifuged, supernatants aspirated, and the cell pellets lysed directly in SDS sample buffer.

Samples in SDS sample buffer were heated at 100°C for 5 minutes. Proteins were separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to Immobilon P membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were blocked, incubated with anti-CD20N, washed, and bound antibodies detected with horseradish peroxidase conjugated to protein A (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). Proteins were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce, Rockford, IL) recorded on Kodak X-OMAT film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) or Fluor-S Max Multi-Imager (Bio-Rad).

Homotypic aggregation

Ramos B cells, 1 × 106 in 1 mL tissue culture medium, were placed into wells of 24-well flat-bottomed plates with 1 μg anti-CD20 or control antibody, and incubated at 37°C for 4 hours. All assays were carried out in duplicate. Extent of cellular aggregation was scored as follows: +/−, less than 10% of cells were clustered; +, 10% to 25% of cells were in small clusters; ++, less than 50% of cells were clustered into medium-sized aggregates; +++, 50% to 75% of cells were in medium to large aggregates; and ++++, 75% to 100% of cells were in large aggregates.

Results

For the initial epitope mapping studies, mAbs 1F5, 2H7, and B1 were selected for analysis; B1 is the prototypic CD20 mAb, 2H7 is representative of mAbs previously thought to recognize the same epitope as B1, and 1F5 has distinct specificity. None of these mAbs was capable of detecting CD20 by immunoblot (data not shown), indicating that their epitopes are conformational.

Mutagenesis of the human CD20 extracellular region

The human CD20 cDNA sequence predicts a protein that is 73% identical to murine CD20 with regions of greatest similarity in the transmembrane domains.6-8 27 The extracellular region is less conserved, differing at 16 of the approximate 43 amino acid residues (Figure 1A). Among these 16 residues are 8 nonconservative differences, most of which are located within a 10-amino acid stretch (ESLNFIRAHT). A synthetic peptide with this sequence failed to block binding of mAbs 1F5, 2H7, and B1 to Raji B cells (data not shown), suggesting that either these residues are not represented within the corresponding epitopes or that the secondary structure assumed by the soluble peptide was insufficient for antibody binding.

Binding of CD20 mAbs is abolished by mutation of alanine-170 and proline-172.

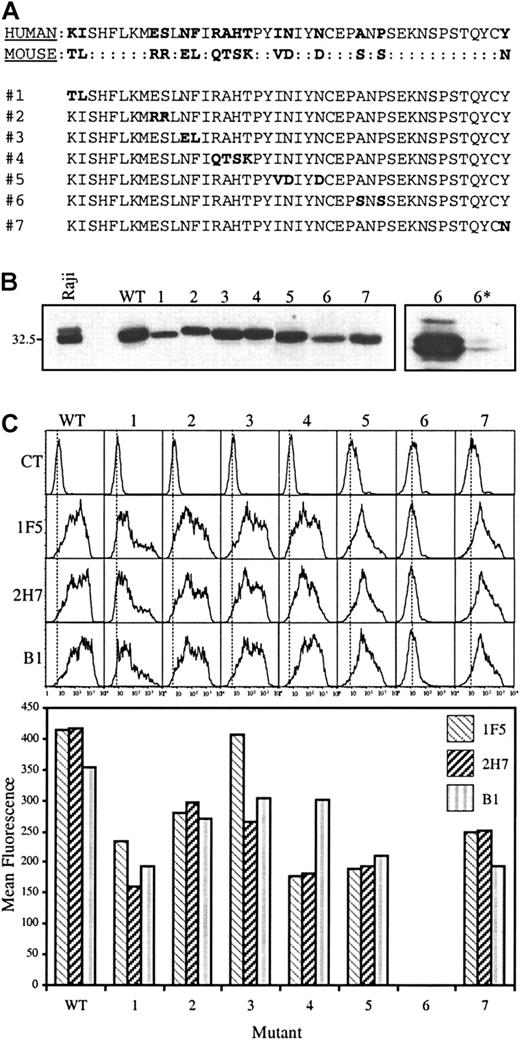

(A) The human CD20 extracellular sequence was mutated toward the murine sequence to produce constructs 1 through 7. Mutated residues in constructs 1 through 7 are highlighted in bold. (B) Wild-type (WT) human CD20 and constructs 1 through 7 were expressed in HEK293 cells and equimolar amounts of cell lysates were tested for CD20 expression by immunoblot analysis using a polyclonal antibody generated against a cytoplasmic peptide (anti-CD20N). To confirm cell surface expression of construct 6, transfected cells were either untreated or treated with proteinase K before lysis (lanes 6 and 6*, far right). (C) Binding of anti-CD20 mAbs 1F5, 2H7, and B1 to transfected cells was monitored by flow cytometry (top); mean fluorescence values, with the isotype control values subtracted, are shown in the bar graph below. Results are representative of 6 independent experiments.

Binding of CD20 mAbs is abolished by mutation of alanine-170 and proline-172.

(A) The human CD20 extracellular sequence was mutated toward the murine sequence to produce constructs 1 through 7. Mutated residues in constructs 1 through 7 are highlighted in bold. (B) Wild-type (WT) human CD20 and constructs 1 through 7 were expressed in HEK293 cells and equimolar amounts of cell lysates were tested for CD20 expression by immunoblot analysis using a polyclonal antibody generated against a cytoplasmic peptide (anti-CD20N). To confirm cell surface expression of construct 6, transfected cells were either untreated or treated with proteinase K before lysis (lanes 6 and 6*, far right). (C) Binding of anti-CD20 mAbs 1F5, 2H7, and B1 to transfected cells was monitored by flow cytometry (top); mean fluorescence values, with the isotype control values subtracted, are shown in the bar graph below. Results are representative of 6 independent experiments.

A mutation strategy was then designed in which extracellular residues in the human CD20 sequence that differ from those in the mouse were replaced with those from the equivalent positions in the murine sequence. As indicated in Figure 1A, 7 constructs were generated. In construct 1, for example, KI in the human sequence was replaced with TL, but all other residues remained unchanged. The constructs were expressed in HEK293 cells, and the cells collected for analysis 2 to 3 days after transfection. All constructs were expressed, as shown by immunoblotting using a polyclonal antibody generated against a cytoplasmic peptide (Figure 1B), although there was some variability in the degree of expression. Recognition of the constructs by mAbs directed against extracellular epitopes was assessed by flow cytometry (Figure 1C). The only construct not recognized by mAbs 1F5, 2H7, or B1, was construct 6. Extracellular protease digestion of cells transfected with construct 6 led to loss of the full-length 33- to 35-kd protein, confirming its expression at the cell surface (Figure 1B, far right, lanes 6 and 6*).

Mutagenesis of the murine CD20 extracellular region

The murine sequence was then mutated in a complementary strategy, replacing residues that differ from human CD20 with those from the equivalent positions in the human sequence (Figure2A). First, a chimera was constructed in which the entire extracellular region in the human sequence was replaced with that from the mouse (h/m CD20). By constructing a chimera it was possible to use existing antisera against cytoplasmic peptides in human CD20 to confirm expression of the chimeric proteins. As expected, mAbs directed against extracellular epitopes of human CD20 did not recognize the h/m chimera (Figure 2C). Initially, 4 constructs were generated (Figure 2A); one in which SNS in the murine sequence was replaced with ANP (construct C); a second in which only the proline residue was introduced (construct D); a third in which VDxxD in the mouse was replaced with INxxN from the human (construct B); fourth, a construct that accommodated all of the remaining differences in the amino-terminal half of the sequence (construct A). These constructs were transfected into HEK293 cells and expression was confirmed in all cases by immunoblot (Figure 2B). There was no binding of mAbs 1F5, B1, or 2H7 to cells expressing either construct A or construct B, as assessed by flow cytometry (Figure 2C). Cell surface expression of these constructs, as well as the h/m chimera, was confirmed by protease digestion as described for construct 6 in Figure 1 (data not shown). Remarkably, the epitope recognized by the B1 mAb was completely recovered by construct C, and partially by construct D. There was partial recovery of 1F5 binding by construct C. Binding of 2H7 was not rescued to a significant extent by any of the mutations in constructs A through D, although there was detectable, albeit extremely low, binding of 2H7 to construct C.

Conversion of SNS in the murine CD20 sequence to ANP recovers binding of B1.

(A) The extracellular region of human CD20 was replaced with that from the murine sequence to generate the h/m chimera. Residues in the murine sequence were then mutated to produce constructs A through D. Mutated residues in constructs A through D are highlighted in bold. (B) Wild-type human CD20 (WT), h/m CD20, and constructs A through D were expressed in HEK293 cells and CD20 expression assessed by immunoblot analysis as in Figure 1. (C) Binding of anti-CD20 mAbs 1F5, 2H7, and B1 to transfected cells was monitored by flow cytometry (top); mean fluorescence values, with the isotype control values subtracted, are shown in the bar graph below. Results are representative of 4 independent experiments.

Conversion of SNS in the murine CD20 sequence to ANP recovers binding of B1.

(A) The extracellular region of human CD20 was replaced with that from the murine sequence to generate the h/m chimera. Residues in the murine sequence were then mutated to produce constructs A through D. Mutated residues in constructs A through D are highlighted in bold. (B) Wild-type human CD20 (WT), h/m CD20, and constructs A through D were expressed in HEK293 cells and CD20 expression assessed by immunoblot analysis as in Figure 1. (C) Binding of anti-CD20 mAbs 1F5, 2H7, and B1 to transfected cells was monitored by flow cytometry (top); mean fluorescence values, with the isotype control values subtracted, are shown in the bar graph below. Results are representative of 4 independent experiments.

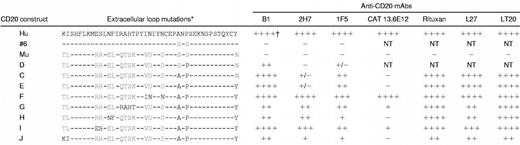

Figure 2 shows that replacement of residues SxS in the mouse sequence with AxP was sufficient to completely reconstitute the epitope of the B1 mAb but not that of 2H7 or 1F5. Additional mutant constructs were then generated to investigate the requirements for 2H7 and 1F5 binding. Because AxP was a minimum requirement for 1F5 and 2H7 binding (Figure1), SxS was replaced with AxP in all of the mouse/human CD20 chimeric constructs subsequently produced (Table1). In construct E, Y284, located at the carboxyl-terminal end of the extracellular human sequence, replaced N at the equivalent position in the mouse sequence. This mutation had no significant effect on antibody binding compared to construct C and was included in all subsequent constructs. Next, VDxxD in the murine sequence was replaced with INxxN (construct F). The protein product from this construct completely recovered binding of the 2H7 mAb and enhanced the binding of 1F5 (Table 1). Also shown in Table1 is the analysis of 4 additional mAbs: CAT 13.6E12, LT20, L27, and rituximab. Epitopes recognized by LT20, L27, and rituximab, like that of B1, were fully reconstituted in construct C (AxP). The epitope recognized by CAT 13.6E12 was similar to that of 2H7 in that it was not recovered by construct C (AxP) or E (AxP/Y), but was fully recovered by construct F (INxxN/AxP/Y).

Antibody reactivity with CD20 extracellular loop mutants

NT indicates not tested. All antibodies were tested at least 3 times against each construct.

Black letters are human sequence; gray letters are murine sequence; black dashes are identical to human.

Reactivity is shown on a scale of + (weak positive) to ++++ (maximum positive). +/− indicates borderline positive.

To assess whether any of the remaining amino acid differences contributed to epitopes recognized by those mAbs that did not bind well to constructs C or E, mutations were made to introduce the relevant human residues into the equivalent positions in the murine chimeric construct E (AxP/Y). Mutation of QTSK to RAHT (construct G) or RR to ES (construct I) increased the binding of mAbs 2H7 and CAT 13.6E12 compared to construct E. Mutation of EL to NF (construct H) increased the binding of 2H7 but not CAT 13.6E12. None of these mutations increased binding of 1F5, which was the only epitope not fully reconstituted by any of the constructs generated in this study.

Additional fine specificity differences among CD20 mAbs suggested by their biologic activities

A panel of 16 CD20-reactive mAbs was screened and divided into 4 groups according to their ability to bind to construct C (AxP; Table2). Only one antibody, CAT 13.6E12, mentioned earlier, was consistently and completely unable to recognize the protein product of this construct (group I in Table 2). This mAb, like most CD20 mAbs, failed to induce Ramos cell aggregation but strongly induced translocation of CD20 to the detergent-insoluble fraction. The majority of CD20 mAbs was similar to B1 insofar as the AxP mutation in the murine sequence largely or completely reconstituted the epitope (group IV in Table 2). However, fine specificity differences among these mAbs can be inferred from marked variance in their ability to induce homotypic aggregation of Ramos B cells and to induce detergent insolubility of CD20. Only B1 and Bly1 induced strong aggregation of Ramos cells. Interestingly, B1 and Bly1 were the only antibodies that were ineffective at inducing CD20 translocation (Table2). Thus, Bly1 and B1 probably recognize an identical epitope. Rituximab fell into group IV but was unusual in that it induced a low level of aggregation and also strongly induced CD20 translocation. The remaining mAbs in group IV did not induce aggregation, strongly induced CD20 translocation, and could not be differentiated from one another using these parameters.

Reactivity of expanded panel of CD20 mAbs

| Group . | AxP reactivity . | Antibody designation . | Homotypic aggregation . | CD20 translocation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | None | CAT 13.6E126 | − | ++++ |

| II | Weak | 2H76, 1C0-1652 | − | ++++, ++ |

| AT802 | ++++ | ++++ | ||

| III | Intermediate | 1F56, B-H202, MEM-972 | − | +++ |

| IV | High | B16, Bly12 | ++++ | − |

| Rituxan3 | ++ | ++++ | ||

| NK12, PDR782, F4B13661, LT205, L275, CAT 13.7H82 | − | +++ to ++++ |

| Group . | AxP reactivity . | Antibody designation . | Homotypic aggregation . | CD20 translocation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | None | CAT 13.6E126 | − | ++++ |

| II | Weak | 2H76, 1C0-1652 | − | ++++, ++ |

| AT802 | ++++ | ++++ | ||

| III | Intermediate | 1F56, B-H202, MEM-972 | − | +++ |

| IV | High | B16, Bly12 | ++++ | − |

| Rituxan3 | ++ | ++++ | ||

| NK12, PDR782, F4B13661, LT205, L275, CAT 13.7H82 | − | +++ to ++++ |

Superscripts indicate the number of times each antibody was tested for reactivity against the m/h AxP chimera (construct C). At least 2 homotypic aggregation and translocation experiments were performed for each antibody, and were scored as described in “Materials and methods.”

Two mAbs were identified, which, like 2H7, bound very weakly to construct C (AxP) (group II, Table 2). One of these, AT80, was the only mAb in the entire panel that strongly induced both cellular aggregation and CD20 translocation, and therefore likely has a unique fine specificity. Finally, 1F5 and 2 other mAbs showed an intermediate degree of reactivity with construct C (AxP; group III, Table 2). Further differentiation of fine specificity among these mAbs could not be determined, because all 3 mAbs strongly induced CD20 translocation and did not induce cellular aggregation. Antibodies in the panel were of various IgG isotypes but this did not correlate with or account for any of the differences in reactivity observed.

The CD20 epitope recognized by mAb 2H7 is presented only on oligomeric complexes

Altogether, 7 different patterns of reactivity were distinguished when 16 mAbs were compared for their ability to bind to the AxP construct C and to induce homotypic aggregation or CD20 translocation: 2 in group II, 3 in group IV, and those in groups I and III. It seemed unlikely that the small extracellular loop of CD20 could present the variety of epitopes necessary to account for this array of fine specificity differences. We hypothesized that some epitopes are comprised of residues contributed by different CD20 molecules adjacent to one another in a homo-oligomeric complex. Others have reported the detection of CD20 dimers and tetramers after chemical cross-linking of cell surface proteins10; therefore, we sought detergent lysis conditions that would retain the integrity of such complexes. Raji B cells were lysed either in Triton X-100 or in digitonin and the postnuclear cleared lysates were layered onto 5% to 40% linear sucrose density gradients and centrifuged to equilibrium; fractions were collected and probed for the presence of CD20 by immunoblot. CD20 migrated on the gradient as a monomer when the cells were lysed in Triton X-100 (Figure 3A). In contrast, when the cells were lysed in digitonin, CD20 migrated to a position corresponding to about 200 kd (Figure 3A). CD20 protein formed the bulk of the mass of the approximate 200-kd complex, as demonstrated by its immunoprecipitation from digitonin lysates followed by silver staining (not shown). These data are consistent with chemical cross-linking experiments,10 and indicate that the CD20 complex includes multiple (probably 4) CD20 molecules and additional minor component(s).

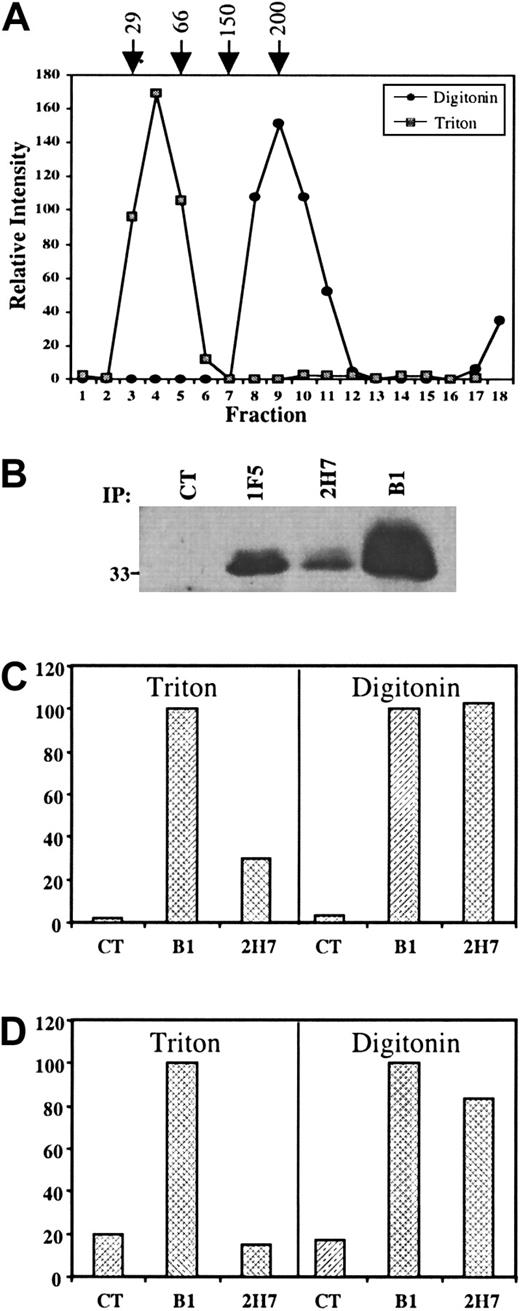

Differential sensitivity of CD20 epitopes to detergent lysis.

(A) Raji B cells were lysed in either 1% Triton X-100 or 1% digitonin and cleared lysates were layered on top of 5% to 40% linear sucrose density gradients and centrifuged to equilibrium. Fractions were collected from the top of the gradient and probed by immunoblot using a polyclonal antibody raised against a cytoplasmic CD20 peptide (anti-CD20N). Densitometry analysis was performed and the results plotted to generate the graphs shown. Molecular weight standards were run in parallel samples (arrows). (B) Immunoprecipitation of CD20 by mAbs 1F5, 2H7, and B1 from Raji B cells lysed in 1% Triton X-100. The mAbs were added to cleared (13 000g) lysates as indicated to immunoprecipitate CD20. Samples were analyzed by anti-CD20N immunoblot. (C) Immunoprecipitation of CD20 by mAbs 2H7 and B1 from Raji B cells lysed in either 1% Triton X-100 or in 1% digitonin. The mAbs were added to cleared (13 000g) lysates as indicated. Anti-CD20N immunoblots were analyzed by densitometry and the relative density of the CD20 bands was expressed as the percent of the amount precipitated by B1. (D) As in panel C, except that the lysates were cleared at 100 000g for 1 hour. Note the loss of 2H7-precipitable CD20 from Triton lysates.

Differential sensitivity of CD20 epitopes to detergent lysis.

(A) Raji B cells were lysed in either 1% Triton X-100 or 1% digitonin and cleared lysates were layered on top of 5% to 40% linear sucrose density gradients and centrifuged to equilibrium. Fractions were collected from the top of the gradient and probed by immunoblot using a polyclonal antibody raised against a cytoplasmic CD20 peptide (anti-CD20N). Densitometry analysis was performed and the results plotted to generate the graphs shown. Molecular weight standards were run in parallel samples (arrows). (B) Immunoprecipitation of CD20 by mAbs 1F5, 2H7, and B1 from Raji B cells lysed in 1% Triton X-100. The mAbs were added to cleared (13 000g) lysates as indicated to immunoprecipitate CD20. Samples were analyzed by anti-CD20N immunoblot. (C) Immunoprecipitation of CD20 by mAbs 2H7 and B1 from Raji B cells lysed in either 1% Triton X-100 or in 1% digitonin. The mAbs were added to cleared (13 000g) lysates as indicated. Anti-CD20N immunoblots were analyzed by densitometry and the relative density of the CD20 bands was expressed as the percent of the amount precipitated by B1. (D) As in panel C, except that the lysates were cleared at 100 000g for 1 hour. Note the loss of 2H7-precipitable CD20 from Triton lysates.

The 2H7 mAb precipitates only a small subset of CD20 protein from Triton X-100 lysates compared to B1 and 1F5 (Figure 3B), even though analysis by flow cytometry indicates that it binds at least as well as B1 and 1F5 to CD20 at the cell surface14 (Figure 1). We predicted that this CD20 subset was associated with membrane rafts, because 2H7 coprecipitates a 75- to 80-kd tyrosine phosphorylated protein that we subsequently identified as PAG/Cbp, an adaptor protein only found in lipid rafts29 30 (unpublished data, June 2000). We reasoned that the 2H7 mAb can only recognize CD20 in its native oligomeric form, which would be preserved in Triton-insoluble membrane rafts, whereas it cannot recognize the monomeric form of CD20 in the soluble fraction of Triton X-100 lysates. To test this hypothesis, CD20 immunoprecipitations were performed from cell lysates prepared with either digitonin or Triton X-100. Immunoprecipitation of CD20 by 2H7 was indeed as effective as B1 when cells were lysed in digitonin (Figure 3C). Ultracentrifugation of Triton X-100 lysates depleted 2H7-precipitable CD20 (Figure 3D), confirming that this subset of CD20 protein was associated with detergent-insoluble membranes.

Discussion

The B1 epitope and AxP

Previously, the B1 and 2H7 mAbs were thought to recognize the same epitope. Indeed, the existing evidence suggested that all antihuman CD20 mAbs, with the exception of 1F5, bound to a single epitope.5 This report shows that 2H7 and B1 unequivocally recognize distinct epitopes and demonstrates a high degree of heterogeneity among 16 mAbs tested. Rituximab was most like the B1 mAb with respect to its reactivity with the AxP h/m chimera (construct C), but was distinct from B1 with respect to its ability to induce CD20 translocation (Table 2).

It is clear from these studies that the sequence AxP at positions 170-172 in human CD20 is a critical determinant in the secondary structure of the extracellular loop because its mutation destroyed the epitopes of all 3 CD20 mAbs tested. Replacement of the second serine in the equivalent mouse sequence SxS with a proline residue was sufficient to allow binding of B1, although replacement of both serines with alanine and proline was necessary to fully reconstitute the B1 epitope. Site-directed mutagenesis, although a powerful tool in epitope mapping studies, cannot define contact sites, and it is not possible to conclude that AxP are contact residues in the B1 epitope. Crystallographic determinations have shown that there are at least 15 contact residues in the binding regions of antigen-antibody complexes.31 It can be inferred from creation of the B1 binding site in the murine CD20 sequence by replacement of only 2 residues, that most, if not all, contact residues for the B1 mAb are shared between human and mouse CD20. Proline residues introduce kinks into polypeptide backbones, often interrupting regions of defined secondary structure. Whether or not AxP is included in the contact site, it is likely that this sequence defines the conformation of contact residues at neighboring or distant sites.

The 2H7 epitope and INxxN

The 2H7 epitope was recreated in the AxP murine chimera by the replacement of VDxxD with INxxN. This was a surprising finding because these are conservative mutations. Again, it cannot be determined whether INxxN are contact residues in the 2H7 binding site or residues that are essential for defining the conformational epitope at a distant site. The INxxN sequence is not critical for maintenance of the 2H7 epitope in human CD20, because its mutation did not abrogate antibody binding (Figure 1). Further, INxxN is insufficient to recreate the 2H7 epitope in the background of the murine sequence (Figure 2). However, INxxN was an essential determinant in the creation of the 2H7 epitope when AxP was included in the murine sequence (Table 1).

B1 versus 2H7 epitopes

Others have reported,5 and we have confirmed (unpublished data, March 2000), that 2H7 blocks the binding of B1 to its epitope. It is possible that the paratopes of the 2 mAbs have overlapping footprints or that there is steric hindrance from the Fc regions of the antibodies. In support of the latter we have found that Fab fragments of 2H7 do not effectively block the binding of B1, suggesting that the epitopes are spatially distinct (unpublished data, March 2000). Although neither B1 nor 2H7 is capable of recognizing denatured epitopes, there is a marked difference in the sensitivity of the epitopes to detergent lysis. B1 efficiently precipitates CD20 from Triton X-100 lysates, whereas 2H7 does not. Density gradient centrifugation analyses indicated that Triton-soluble CD20 exists in monomeric form (Figure 3A). Therefore, the ability of B1 to precipitate CD20 from Triton lysates indicates that the B1 epitope is retained on CD20 monomers. A small proportion of CD20 molecules are constitutively associated with Triton-insoluble lipid rafts in unstimulated cells, and our data are consistent with the interpretation that it is this population that is recognized by 2H7 in Triton X-100 lysates. The 2H7 epitope is retained in digitonin lysates in which CD20 is solubilized as an approximate 200-kd complex. Together these data provide strong evidence that retention of the 2H7 epitope requires the integrity of the multimeric complex.

The 1F5 epitope

The molecular basis for the activating properties of the 1F5 mAb was not revealed by this analysis, but this mAb was the only one among 7 tested against the full panel of h/m mutants, for which full binding was not recovered by any of the mutations made in the murine sequence (Table 1). The epitope that it recognizes is therefore unique. 1F5 falls between B1 and 2H7 with respect to its ability to precipitate CD20 from Triton lysates (Figure 3B), indicating that its epitope is likely to be partially dependent on the integrity of the CD20 oligomeric complex. Recently, analyses of the genomic databases have revealed a large family of CD20 related genes.32,33Several members of this MS4A gene family are expressed in hematopoietic cells and at least 3 of them, in addition to CD20, are expressed in B cells.33 Whether or not heterologous associations between members of this family can form oligomeric complexes remains to be determined, but would be expected to further increase the array of possible epitopes.

Nonconservative amino acid differences between human and mouse CD20

The creation of B1 and 2H7 human CD20 epitopes in the mouse sequence by replacement of residues that differ only conservatively underscores the fact that antibody binding sites cannot be predicted based on sequence differences between homologs. Most residues in the human CD20 sequence that are radically different at the equivalent positions in the murine sequence were not essential for mAb recognition (Figure 1). However, it is likely that some of these residues are included in the epitopes of some CD20 mAbs, because their introduction into the AxP murine chimera enhanced the binding of some antibodies (Table 1).

Most mAbs generated against native proteins are directed against nonlinear determinants, and antihuman CD20 mAbs are clearly no exception. Nevertheless, considering the small size of the extracellular region of CD20, it is remarkable that we could discriminate at least 7 different patterns of reactivity among 16 CD20 mAbs. This analysis revealed that the induction of homotypic aggregation is an unusual characteristic among CD20 mAbs, in contrast to the relatively common ability to induce CD20 insolubility and translocation into lipid rafts. We, and others, have shown that the B-cell antigen receptor also translocates into lipid rafts after ligation.34-36 Colocalization of the BCR and CD20 in rafts may serve to localize calcium influx (through the putative CD20 calcium channel) to regions proximal to antigen engagement. No ligand for CD20 has yet been identified, but it is possible that ligand binding mediates CD20 translocation to rafts in vivo. Results from this study predict that binding sites for such a ligand would be created by neighboring CD20 molecules in an oligomeric complex.

It has been suggested that CD20 delivers an apoptotic signal responsible for some of the cell death underlying therapeutic efficacy of rituximab. Because lipid rafts concentrate src-family kinases and other signaling effectors, anti–CD20-induced signals may be secondary to raft aggregation occurring as a consequence of CD20 translocation. Interestingly, in support of this idea, aggregation of rafts by cross-linking either glycosphingolipid GM1 or glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked proteins, which are constitutively localized to rafts, was shown to lead to apoptosis.37Rafts exclude most integral membrane proteins and antibody-mediated translocation of CD20 into rafts is unusual; ligation of several other surface proteins expressed in B cells did not result in their redistribution into Triton-insoluble rafts.36 Raft association of antibody-bound CD20 may partly explain the particular efficacy of CD20 as an immunotherapeutic target, and those antibodies such as rituximab, which most efficiently induce CD20 translocation, may confer some added benefit.

We thank L. Robertson for assistance with flow cytometry; Dr L. Ayer for assistance with cellular aggregation and CD20 translocation experiments; T. Kryzanowski for secretarial assistance; C. Mutch, R. Petrie, and Dr C. Brown for comments on the manuscript; and Dr J. Ledbetter and Dr A. Hekman for providing antibodies.

Supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and the Weiss Memorial Endowment Fund. J.P.D. is a senior scholar of the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Julie Deans, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Calgary, Health Sciences Center, 3330 Hospital Dr NW, Calgary, Alberta, T2N 4N1, Canada; e-mail:jdeans@ucalgary.ca.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal