Abstract

It is generally believed that homeostatic responses regulate T-cell recovery after peripheral stem cell transplantation (PSCT). We studied in detail immune recovery in relation to T-cell depletion and clinical events in a group of adult patients who underwent PSCT because of hematologic malignancies. Initially, significantly increased proportions of dividing naive, memory, and effector CD4+and CD8+ T cells were found that readily declined, despite still very low numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. After PSCT, increased T-cell division rates reflected immune activation because they were associated with episodes of infectious disease and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). T-cell receptor excision circles (TRECs) were measured to monitor thymic output of naive T cells. Mean TREC content normalized rapidly after PSCT, long before naive T-cell numbers had significantly recovered. This is compatible with the continuous thymic production of TREC+ naive T cells and does not reflect homeostatic increases of thymic output. TREC content was decreased in patients with GVHD and infectious complications, which may be explained by the dilution of TRECs resulting from increased proliferation. Combining TREC and Ki67 analysis with repopulation kinetics led to the novel insight that recovery of TREC content and increased T-cell division during immune reconstitution after transplantation are related to clinical events rather than to homeostatic adaptation to T-cell depletion.

Introduction

Recovery of the immune system from T-lymphocyte depletion of any cause depends on 2 separate mechanisms, peripheral expansion of T cells and naive T-cell production by the thymus.1-6 Regulation of this process is believed to be homeostatic—transplanted or remaining T cells can be induced to expand, and thymic output of naive T cells can be increased. The latter also contributes to the recovery of a broad T-cell repertoire.1,7 Still, immune reconstitution in adults is generally slow and is not always complete.3,8,9 This may be attributable to the age-related involution of thymic tissue. Indeed, children seem to recover faster and to have better reconstitution of their T-cell receptor repertoire than adults do, but only when related to adult normal T-cell values.3 10-13

We aimed to investigate whether the immune system is indeed capable of homeostatic responses to changes in peripheral T-cell counts. We studied the contribution of the different mechanisms involved in immune reconstitution in a group of adult patients with hematologic malignancies after allogeneic peripheral stem cell transplantation (PSCT) with a T-cell–depleted graft. Under this condition of reconstitution of the T-cell pool in an immune system that is assumed to be empty, we measured peripheral cell division by analyzing expression of the activation antigen Ki67 in naive, memory, and effector CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets. In addition, we sought to evaluate thymic output by analysis of T-cell receptor excision circles (TRECs). These excision circles are formed during the T-cell receptor rearrangement process that T cells undergo during maturation in the thymus.14,15 Naive T cells that have recently emigrated from the thymus contain a certain, relatively high TREC content, and quantification of this TREC content has been considered a measure of thymic function.16,17 More recently, however, the interpretation of TREC data in various clinical conditions has been shown to be more complex than anticipated.18

The purpose of this study was to better understand the relative importance of factors involved in reconstitution of the adult immune system and to identify the underlying mechanisms that drive those factors. Immune reconstitution can be indicated by the recovery of peripheral blood CD4+ T cells, even when only a fraction of the T-cell pool resides in the peripheral blood.19 By measuring peripheral cell division rates in parallel with an analysis of TREC dynamics and relating these data to the clinical status of patients and to the recovery of peripheral blood T-cell numbers, we here offer a new interpretation of posttransplantation T-cell division rates and TREC data.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients

Twenty-two patients with hematologic malignancies who underwent allogeneic HLA-matched PSCT were included. Grafts were depleted for T and B cells by incubation with the humanized anti-CD52 antibody Campath-1H, to reduce the risk for graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Patients followed a standard conditioning regimen: cyclophosphamide 60 mg/kg per day for 2 days (days −6 and −5) and single-dose total body irradiation (9 Gy, day −1) with shielding of eyes and lungs. Peripheral cell division and thymic T-cell production were analyzed at different time points after PSCT using freshly obtained samples of peripheral blood. At all time points, the clinical status of patients was monitored. Diagnosis and grading of GVHD were by histopathologic analysis of skin biopsy, liver function tests, and incidence of diarrhea. Patients were monitored for cytomegalovirus reactivation at weekly intervals (pp65 monoclonal antibody [mAb]) during the first 3 months after transplantation. Four patients were studied longitudinally, at 6 weeks and at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after PSCT. Healthy volunteers of comparable age were included as controls (median age of patients, 35 years; range, 20-55 years). On study entry, patients gave institutional review board–approved informed consent.

Peripheral cell division

Naive (CD27+CD45RO−) and memory (CD45RO+ and CD27+ or CD27−) CD4+ T cells and naive (CD27+CD45RO−), memory (CD45RO+and CD27+ or CD27−), and effector (CD27−CD45RO−) CD8+ T cells were defined as described previously.20,21 Cell proliferation was measured by analyzing Ki67, a protein pivotal for cell division that is expressed exclusively by cells that are in cell cycle,22 as reported elsewhere.23 Briefly, 500 μL heparinized blood was incubated with CD4- or CD8-PerCP mAb, CD45RO–phycoerythrin mAb (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA), and biotinylated CD27 mAb (CLB, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), followed by incubation with streptavidin–allophycocyanin (Becton Dickinson). Red blood cells were lysed, and lymphocytes were fixated (FACS Lysing Solution; Becton Dickinson), permeabilized (FACS Permeabilization Buffer; Becton Dickinson), incubated with Ki67–fluorescein isothiocyanate mAb (Immunotech, Marseilles, France), and fixated (Cellfix; Becton Dickinson). Ki67 expression was analyzed on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson) with CellQuest software.

TREC measurements

PBMCs were obtained by Ficoll-Hypaque density-gradient centrifugation from heparinized blood, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were isolated by magnetic bead separation over columns using the MiniMACS multisort kit according to manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, Sunnyvale, CA). With this technique, at least 90% purity was achieved. DNA was purified from CD4+and CD8+ fractions using the QIAamp Blood Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). To detect Signal joint (Sj) TRECs, a real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction method was used, as described previously.18 The Cα constant region was used as an internal control measurement, and an Sj standard18 was included to calculate the number of Sj copies present. From the average TREC content, as measured per microgram DNA, TREC content per T cell was calculated by dividing TREC content by 150 000 (assuming that 1 μm DNA corresponds to 150 000 cells). The absolute number of TREC+ CD4+ and TREC+ CD8+ T cells was calculated by multiplying the average CD4+ and CD8+ TREC content by the number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Patient and control values were compared with the Mann-WhitneyU test. Correlations were calculated using Spearman (rs) and Pearson (rp) correlation coefficients, depending on the outcome of Shapiro-Wilk W tests of normality.

Results

Peripheral blood T-cell numbers and T-cell division rates

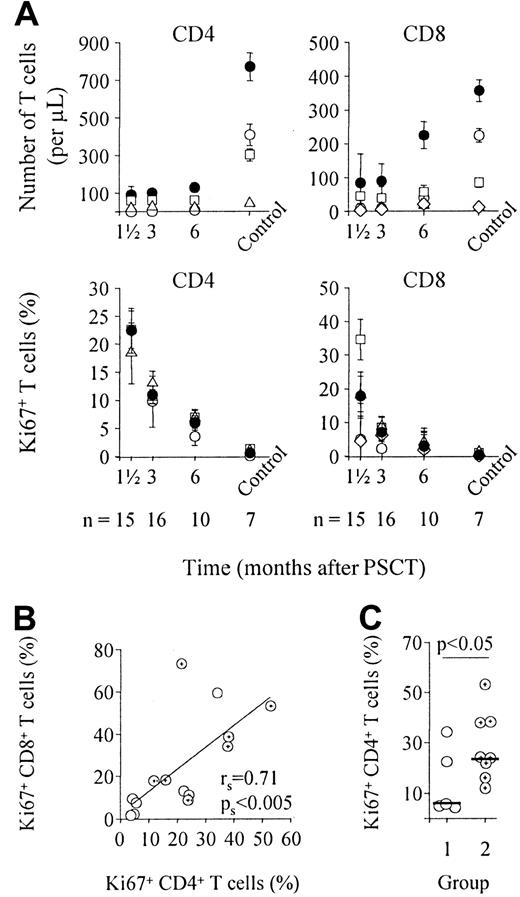

Quantitative T-cell recovery was analyzed for naive, CD27+ and CD27− memory CD4+ T cells and for naive, CD27+ and CD27− memory and CD27− effector CD8+ T cells (Figure1A, upper panels). Restoration of T-cell subsets was slow. Six months after PSCT, the total number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was still significantly lower than control values (P < .01), confirming previous reports.9 This was related to significantly lower numbers of naive and CD27+ and CD27− memory CD4+ T cells and naive CD8+ T cells (P < .05). In parallel, we measured Ki67 expression in naive and memory CD4+ T-cell subsets and in naive, memory, and effector CD8+ T-cell subsets (Figure 1A, lower panels). Six weeks after PSCT, the proportion of dividing cells was significantly increased compared with healthy controls (P < .001 for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells). This was attributed to significantly increased division rates in naive, CD27+, and CD27− memory and effector CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets (P < .005). Cell division rates in all T-cell subsets declined immediately after PSCT, whereas CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell numbers were still significantly lower than in healthy controls (Figure 1A). CD4+ and CD8+T-cell division rates did not correlate with peripheral blood T-cell numbers (rs = −0.35 and rs = −0.38, respectively; data not shown). The proportion of Ki67+CD4+ T cells did correlate significantly with the proportion of Ki67+CD8+ T cells (Figure 1B), which suggests that CD4+ and CD8+ T cell division are driven by a common factor.

T-cell recovery and peripheral T-cell division after PSCT.

(A) Depicted are median numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and naive, memory, and effector CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets (upper panels) and median values of Ki67 expression in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and T-cell subsets (lower panels) at sequential time points after PSCT. Note that at 6 weeks, the percentage of naive CD4+ T cells was too low in most patients to determine Ki67 expression in this subset. Black circles, CD4+ (left panels) or CD8+ (right panels) T cells; white circles, naive T cells; white squares, CD27+memory T cells; white triangles, CD27− memory T cells; white diamonds, CD27− effector T cells. (B) The proportion of dividing CD4+ T cells did correlate significantly with the proportion of dividing CD8+ T cells, suggesting that division is driven by a common factor. (C) Patients with no signs of infectious diseases (group 1, n = 6) had lower proportions of dividing CD4+ T cells than patients with documented inflammatory complications, such as GVHD, reactivation of CMV, or fungal pneumonia (group 2, n = 8). Note that patient 12 was not assigned to either group because she was admitted to the hospital for severe dehydration at this time point (see Table 1). White circles, group 1 patients; cross-hair circles, group 2 patients (B, C). Horizontal bars indicate median values in panel C. Depicted in panels B and C are data obtained 6 weeks after PSCT (n = 15). Similar results were obtained for the other time points and for CD8+ T cells (data not shown).

T-cell recovery and peripheral T-cell division after PSCT.

(A) Depicted are median numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and naive, memory, and effector CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets (upper panels) and median values of Ki67 expression in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and T-cell subsets (lower panels) at sequential time points after PSCT. Note that at 6 weeks, the percentage of naive CD4+ T cells was too low in most patients to determine Ki67 expression in this subset. Black circles, CD4+ (left panels) or CD8+ (right panels) T cells; white circles, naive T cells; white squares, CD27+memory T cells; white triangles, CD27− memory T cells; white diamonds, CD27− effector T cells. (B) The proportion of dividing CD4+ T cells did correlate significantly with the proportion of dividing CD8+ T cells, suggesting that division is driven by a common factor. (C) Patients with no signs of infectious diseases (group 1, n = 6) had lower proportions of dividing CD4+ T cells than patients with documented inflammatory complications, such as GVHD, reactivation of CMV, or fungal pneumonia (group 2, n = 8). Note that patient 12 was not assigned to either group because she was admitted to the hospital for severe dehydration at this time point (see Table 1). White circles, group 1 patients; cross-hair circles, group 2 patients (B, C). Horizontal bars indicate median values in panel C. Depicted in panels B and C are data obtained 6 weeks after PSCT (n = 15). Similar results were obtained for the other time points and for CD8+ T cells (data not shown).

Clinical events

After transplantation, patients are at risk for GVHD and, because of severe T-cell depletion, are susceptible to infection.19 Both conditions may also induce increased proportions of T cells to divide. Therefore, we studied the relation between Ki67 expression and clinical status of patients. We divided patients into 2 groups, those who did not suffer from clinically documented infections or GVHD at the time of analysis (group 1) and those who did (group 2). Individual data, measured 6 weeks after PSCT, are depicted in Table 1. The proportion of dividing CD4+ T cells was significantly higher in the group with GVHD or in the group with documented infections (Figure 1C;P < .05). Similar results were obtained for the CD8+ T cells and for the other time points (data not shown). The recovery rate of T-cell numbers was similar between both groups.

Clinical conditions and peripheral cell division rates 6 weeks after PSCT

| Patient . | Clinical condition (6 weeks after PSCT) . | Group . | Ki67+T cells, % . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ . | CD8+ . | |||

| 1 | GVHD grade 1 | 2 | 21.6 | 73.1 |

| 2 | GVHD grade 2 | 2 | 24.1 | 11.1 |

| 3 | No infections or GVHD | 1 | 4.8 | 2.2 |

| 4 | GVHD grade 1 | 2 | 37.9 | 33.9 |

| 5 | Fungal dermatitis | 2 | 23.8 | 8.6 |

| 6 | No infections or GVHD | 1 | 4.2 | 9.4 |

| 7 | No infections or GVHD | 1 | 22.4 | 13.0 |

| 8 | GVHD grade 2 | 2 | 53.1 | 53.1 |

| 9 | No infections or GVHD | 1 | 34.2 | 59.4 |

| 10 | No infections or GVHD | 1 | NT | NT |

| 11 | No infections or GVHD | 1 | 5.6 | 7.4 |

| 12 | Hospitalized: dehydration | Neither | 43.1 | 51.9 |

| 13 | GVHD grade 1 | 2 | 15.9 | 18.1 |

| 14 | Hospitalized: GVHD and cytomegalovirus | 2 | 11.8 | 17.8 |

| 15 | GVHD grade 1 | 2 | 38.2 | 38.5 |

| Patient . | Clinical condition (6 weeks after PSCT) . | Group . | Ki67+T cells, % . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ . | CD8+ . | |||

| 1 | GVHD grade 1 | 2 | 21.6 | 73.1 |

| 2 | GVHD grade 2 | 2 | 24.1 | 11.1 |

| 3 | No infections or GVHD | 1 | 4.8 | 2.2 |

| 4 | GVHD grade 1 | 2 | 37.9 | 33.9 |

| 5 | Fungal dermatitis | 2 | 23.8 | 8.6 |

| 6 | No infections or GVHD | 1 | 4.2 | 9.4 |

| 7 | No infections or GVHD | 1 | 22.4 | 13.0 |

| 8 | GVHD grade 2 | 2 | 53.1 | 53.1 |

| 9 | No infections or GVHD | 1 | 34.2 | 59.4 |

| 10 | No infections or GVHD | 1 | NT | NT |

| 11 | No infections or GVHD | 1 | 5.6 | 7.4 |

| 12 | Hospitalized: dehydration | Neither | 43.1 | 51.9 |

| 13 | GVHD grade 1 | 2 | 15.9 | 18.1 |

| 14 | Hospitalized: GVHD and cytomegalovirus | 2 | 11.8 | 17.8 |

| 15 | GVHD grade 1 | 2 | 38.2 | 38.5 |

Patients were grouped based on the presence or absence of infectious complications or GVHD. NT indicates not tested.

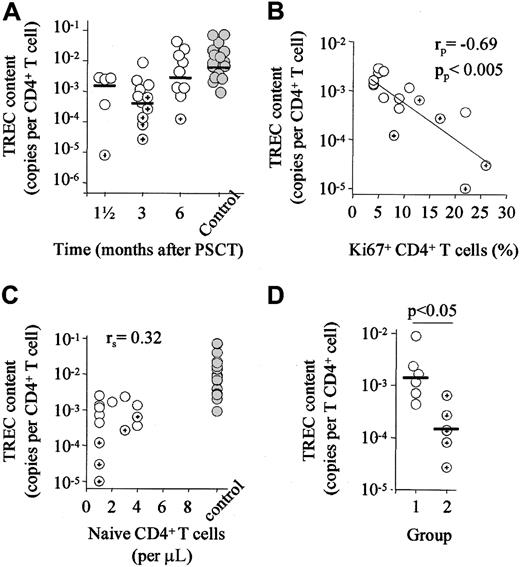

Recovery of TREC content

To assess thymic origin of naive T cells, we measured TREC content (number of TREC copies per T cell) of purified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. After PSCT, the TREC content of CD4+ T cells rapidly normalized. After 6 months, values were not significantly lower than those of healthy controls (Figure2A). Similar results were obtained for CD8+ TREC content recovery (data not shown). TRECs are episomal circles that are diluted during cell division after their formation.14,24 We have recently reported that naive and memory cell division decreases TREC content.18 Among others, the expansion of naive or memory cells, leading to the dilution of TRECs, may decrease the TREC content of purified CD4+and CD8+ T cells. Indeed, CD4+ TREC content correlated negatively with the proportion of dividing CD4+T cells (Figure 2B). No correlation was found between the number of CD27+ CD45RO− naive T cells, a phenotypic rough estimate of thymic output, and TREC content (Figure 2C). Thus, in most patients, TREC content had recovered at time points at which naive T-cell numbers were still extremely low. Thymic function could be hampered by chemotherapy- or radiation-induced damage of this organ and by GVHD.25,26 Low CD4+ TREC content was found in patients with clinically documented GVHD and infectious complications (P < .05; Figure 2D). Nonetheless, the maximal recovery rate of naive T cells was on the order of 108 cells per day in our patients, independent of a history of GVHD. This recovery rate was comparable to that seen in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with depleting doses of CD4 mAbs.8 Similar results as depicted in Figure 2 were obtained for CD8+ TREC content (data not shown).

Rapid recovery of TREC content.

(A) TREC content of purified CD4+ T cells was not significantly different from control values as early as 6 months after PSCT. (B) TREC content correlated significantly with the proportion of dividing CD4+ T cells (C) but not with the number of naive CD4+ T cells. (D) TREC content did depend on the presence of clinically documented GVHD or infectious complications. Hence, patients with inflammatory complications (group 2) had significantly lower CD4+ TREC content than patients without such complications (group 1). Horizontal bars indicate median values. White circles, group 1 patients; cross-hair circles, group 2 patients; gray circles, control values. Depicted are data obtained 3 months after PSCT. Similar data were obtained for the other time points and for CD8+ T cells (data not shown).

Rapid recovery of TREC content.

(A) TREC content of purified CD4+ T cells was not significantly different from control values as early as 6 months after PSCT. (B) TREC content correlated significantly with the proportion of dividing CD4+ T cells (C) but not with the number of naive CD4+ T cells. (D) TREC content did depend on the presence of clinically documented GVHD or infectious complications. Hence, patients with inflammatory complications (group 2) had significantly lower CD4+ TREC content than patients without such complications (group 1). Horizontal bars indicate median values. White circles, group 1 patients; cross-hair circles, group 2 patients; gray circles, control values. Depicted are data obtained 3 months after PSCT. Similar data were obtained for the other time points and for CD8+ T cells (data not shown).

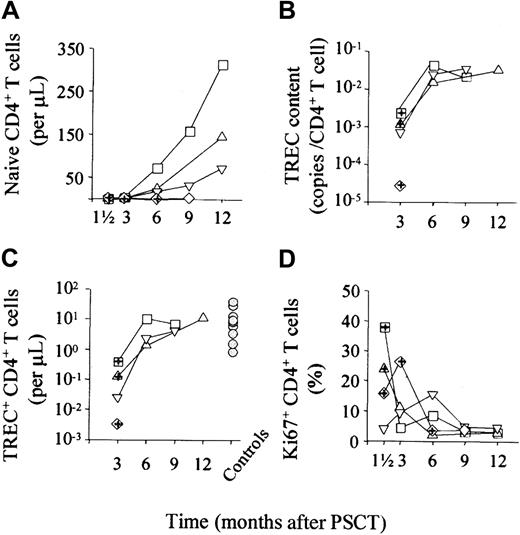

Longitudinal analysis

In 4 patients who underwent PSCT, T-cell recovery, peripheral cell division rates, and TREC content were measured longitudinally (Figure 3). Whereas recovery of naive CD4+ T-cell numbers was variable (Figure3A), 3 of the 4 patients had highly similar recovery kinetics of CD4+ TREC content (Figure 3B) and of the absolute number of TREC+ CD4+ T cells (Figure 3C). Peripheral CD4+ T-cell division rates were related to clinical events and declined in parallel (Figure 3D). Similar kinetics were observed for the CD8+ T cells (data not shown).

Longitudinal analysis of T-cell recovery, Ki67 expression, TREC content, and number of TRECs in 4 patients.

Naive CD4+ T cell numbers (A), CD4+ TREC content (B), and the absolute number of TREC+CD4+ T cells (C) increased over time. Although the kinetics of naive T-cell recovery were different for each patient, those of TREC content and TREC number were similar. Peripheral cell division (D) was associated with clinical events and declined with time. Gray circles in (C) indicate values for healthy controls. In each panel, squares, triangles, and diamonds represent individual patients; symbols with cross-hair indicate infectious complications monitored at that time point (group 2 patients).

Longitudinal analysis of T-cell recovery, Ki67 expression, TREC content, and number of TRECs in 4 patients.

Naive CD4+ T cell numbers (A), CD4+ TREC content (B), and the absolute number of TREC+CD4+ T cells (C) increased over time. Although the kinetics of naive T-cell recovery were different for each patient, those of TREC content and TREC number were similar. Peripheral cell division (D) was associated with clinical events and declined with time. Gray circles in (C) indicate values for healthy controls. In each panel, squares, triangles, and diamonds represent individual patients; symbols with cross-hair indicate infectious complications monitored at that time point (group 2 patients).

Discussion

Immune reconstitution after T-lymphocyte depletion of any cause depends on the peripheral expansion of T cells and naive T-cell production by the thymus. Here we measured the relative contribution and driving factors of both mechanisms to recovery of the adult immune system after PSCT. We found that peripheral T-cell division rates were mainly related to clinical events, either viral disease or GVHD. With time, the initially elevated T-cell division rates declined readily, long before normal T-cell numbers were reached.

It is generally assumed that increased peripheral T-cell division during posttransplantation immune deficiency reflects a homeostatic response to T-lymphocyte depletion.1 Diminished competition for resources would allow T-cell populations to expand until a new steady-state situation is reached.27,28However, in a murine bone marrow transplantation model, peripheral T-cell expansion was shown to be mainly antigen-driven.29In humans recovering from chemotherapy or allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation, increased T-cell susceptibility to spontaneous and activation-induced apoptosis was reported and correlated with immune activation, as measured by HLA-DR expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.30-32 This activation-induced apoptosis declined during the first year after hematopoietic cell transplantation, in accordance with the pattern of immune activation we describe here. One of these studies showed immune recovery to be biphasic. Initial expansion was followed by activation-induced cell death, leading to a significant decline in T-cell numbers after 6 months.30 Thus, the peripheral expansion of T cells may only have a transient effect that is mainly quantitative because initial expansion is by memory T cells of donor origin,33and it does not contribute to restoration of the T-cell receptor repertoire.4 Taken together, increased peripheral T-cell division during the first year of immune recovery may lead to temporal expansion of the T-cell pool; nevertheless, it should be interpreted as a result of antigen-driven immune activation rather than as homeostatic expansion.

Next, we measured the recovery of TREC content to assess the thymic origin of repopulating naive T cells during immune restoration. TREC content (the number of TRECs per 106 T cells) did not increase above normal levels, indicating ongoing cell division.14,18,24 Indeed, posttransplantation cell division rates were negatively correlated with TREC content. Two opposing mechanisms play an important role in TREC dynamics during T-cell reconstitution. First, the entry of TREC+ naive T cells into a virtually empty T-cell pool may at first rapidly increase TREC content of this compartment to supranormal levels. This was previously interpreted to be a sign of thymic rebound, a compensatory increase of thymic output in the process of naive T-cell recovery.7 Second, concomitantly increased peripheral cell division has a negative effect on TREC content. Therefore, low TREC content in patients with GVHD, or a history thereof, does not provide evidence for suppressed thymic function26 but may reflect the expected correlation between GVHD-related increased cell division rates and TREC content, and the rapid recovery of TREC content cannot simply be interpreted as thymic rebound.7

Although absolute numbers of TREC+ T cells may not be influenced directly by peripheral cell division, they are affected by cell death and intracellular degradation of TRECs.18Changes in absolute TREC+ T-cell numbers after PSCT are a composite of thymic output of TREC+ T cells, accumulation of these cells in the periphery over time, and death of these cells.18 The latter may be more extensive in patients with GVHD or infectious complications. It is, therefore, essential to compare the recovery of TRECs with that of naive T-cell numbers, as we showed with the longitudinal recovery dynamics depicted in Figure 3. These data suggest that repopulating naive T cells are indeed of thymic origin, but they do not allow for a quantitative estimation of thymic output of naive T cells.

In conclusion, we combined the recovery of T-cell numbers, peripheral cell division rates, TREC analysis, and clinical data in the evaluation of factors that are involved in immune recovery after PSCT. Contrary to general belief, our findings argue against increased T-cell production as the result of a homeostatic response to T-cell depletion, either through the peripheral proliferation of T cells or through thymic production. Rather it seems that there is a slow but continuous production of thymic T cells to gradually restore the T-cell pool.

We thank the patients and physicians for their participation in this project and Dr Rob de Boer for critical reading of the manuscript.

Supported by the Dutch AIDS Foundation and the Dutch Foundation for Scientific Research (M.D.H., S.A.O., F.M.) and by the Dutch Cancer Society (grant 98-1825) (E.S.d.P., H.R., W.E.F.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Mette D. Hazenberg, Department of Clinical Viro-Immunology, CLB/Sanquin, Plesmanlaan 125, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: m_hazenberg@clb.nl.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal