Key Points

XK1 interacts with TF/FVIIa via the FVIIa protease domain and TF exosite, with much of the FX light chain making no contact with TF/FVIIa.

A novel, membrane-dependent allosteric mechanism controls FX GLA domain binding to TF/FVIIa and may explain the decryption of cell-surface TF.

Visual Abstract

Blood clotting is triggered in hemostasis and thrombosis when the membrane-bound tissue factor (TF)/factor VIIa (FVIIa) complex activates factor X (FX). There are no structures of TF/FVIIa on membranes, with or without FX. Using cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) to address this gap, we assembled TF/FVIIa complexes on nanoscale membrane bilayers (nanodiscs), bound to XK1 and an antibody fragment. XK1 is a FX mimetic whose protease domain is replaced by the first Kunitz-type (K1) domain of the TF pathway inhibitor, whereas 10H10 is a noninhibitory, anti-TF antibody. We determined a cryo-EM structure of a TF/FVIIa/XK1/10H10/nanodisc complex with a resolution of 3.7 Å, allowing us to model all the protein backbones. TF/FVIIa extends perpendicularly from the membrane, interacting with a “handle-shaped” XK1 at 2 locations: the K1 domain docks into FVIIa’s active site, whereas the γ-carboxyglutamate–rich (GLA) domain binds to the TF substrate-binding exosite. The FX and FVIIa GLA domains also contact each other and the membrane surface. Except for a minor contact between the first epidermal growth factor (EGF)–like domain of XK1 and TF, the rest of the FX light chain does not interact with TF/FVIIa. The structure reveals a previously unrecognized, membrane-dependent allosteric activation mechanism between FVIIa and TF, in which a serine-rich loop in TF that partially obscures the TF exosite must undergo a shift to allow access of the FX GLA domain to its final binding location on the membrane-bound TF/FVIIa complex. This mechanism also provides a novel explanation for the otherwise puzzling phenomenon of TF encryption/decryption on cell surfaces.

Introduction

Tissue factor (TF), an integral membrane protein, initiates blood coagulation in normal hemostasis and many thrombotic disorders.1,2 TF binds factor VII (FVII), facilitating its conversion into the active protease, FVIIa. The membrane-bound TF/FVIIa complex then proteolytically activates membrane-bound factors X (FX) and IX (FIX), with FX being preferred under most conditions. Aberrant TF expression can trigger arterial and venous thrombosis, and TF also has nonhemostatic, signaling roles.2

A combination of approaches has shown that TF/FVIIa recognizes FIX and FX as substrates via interactions with not only the FVIIa catalytic cleft,3,4 but also the TF exosite, a cluster of surface-exposed residues near the membrane surface, located ∼60 Å away from the catalytic site.5-14 Encompassing TF residues Y157, K159, S163, G164, K165, K166, and Y185, this exosite is defined by mutations that diminish FIX or FX activation without altering TF/FVIIa binding affinity or the allosteric activation of FVIIa catalytic domain.11 Mutating K165 and K166 caused the largest decreases in FIX9-11,15 and FX5,6,8-11 activation. The γ-carboxyglutamate (GLA)–rich domains of FIX, FX, and FVIIa are implicated as major sites of interaction with the TF exosite region.9,13,16-18

Experimentally determined structures of membrane-bound TF/FVIIa are lacking, but crystal structures of the soluble TF ectodomain (sTF),19 and the sTF/FVIIa complex,20 show that the normally flexible FVIIa is stabilized upon binding the rigid sTF.20,21 Although these structures have facilitated models for how TF allosterically activates the FVIIa catalytic domain,22 understanding TF/FVIIa assembly on membranes and binding to protein substrates has been limited to computational modeling.21,23 Docking studies using models of FX(a) or FIX bound to sTF/FVIIa (usually without membranes) predicted extensive protein-protein contacts between TF/FVIIa and all the domains of FIX or FX.24-27 In contrast, our molecular dynamics (MD) simulation on membranes predicted that FX interacts with TF/FVIIa chiefly via its GLA and protease domains, with little to no contact with its epidermal growth factor (EGF)–like domains.28 Thus, competing models have substantially different predictions for how TF/FVIIa engages FX.

To address how TF/FVIIa recognizes its substrates in the presence of a lipid bilayer, we used single-particle cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) to determine a structure of TF/FVIIa bound to both a FX mimetic, XK1,29 and the Fab fragment of the noninhibitory anti-TF antibody, 10H10,30,31 assembled on phospholipid nanodiscs (Figure 1A). XK1 is a FX substrate mimetic in which the FX light chain (GLA-EGF1-EGF2) is fused to the first Kunitz-type (K1) domain of TF pathway inhibitor (TFPI) to create a slow, tight-binding inhibitor of TF/FVIIa,29 which we confirm interacts with TF/FVIIa in a substrate-like manner.

Biochemical characterization of TF/FVIIa/XK1/10H10 complexes. (A) Schematic of the TF/FVIIa/XK1/10H10/nanodisc complex. (B) TF exosite mutations K165A and K166A reduce the rates of FX activation by TF/FVIIa, with higher PS content moderating this effect. TF was incorporated into small unilamellar liposomes, after which FVIIa and FX were added, and initial rates of FX activation were quantified. Bar graphs show FX activation rates (normalized to WT TF) observed when TF/liposomes contained 5% PS (left) or 20% PS (right). Fold reductions are listed in supplemental Table 1. (C) Elevated XK1 concentrations are required to inhibit TF/FVIIa when TF exosite residues are mutated, with higher PS content moderating this effect. TF/FVIIa was assembled on TF/liposomes with 5% PS (left) or 20% PS (right), then preincubated with varying XK1 concentrations. The residual TF/FVIIa enzymatic activity was quantified (normalized to the FX activation rate without XK1) and plotted vs XK1 concentration, from which IC50 values were derived (listed in supplemental Table 1). Individual data points are graphed in panels B-C (n ≥ 3). ∗∗∗P < .001. WT, wild-type.

Biochemical characterization of TF/FVIIa/XK1/10H10 complexes. (A) Schematic of the TF/FVIIa/XK1/10H10/nanodisc complex. (B) TF exosite mutations K165A and K166A reduce the rates of FX activation by TF/FVIIa, with higher PS content moderating this effect. TF was incorporated into small unilamellar liposomes, after which FVIIa and FX were added, and initial rates of FX activation were quantified. Bar graphs show FX activation rates (normalized to WT TF) observed when TF/liposomes contained 5% PS (left) or 20% PS (right). Fold reductions are listed in supplemental Table 1. (C) Elevated XK1 concentrations are required to inhibit TF/FVIIa when TF exosite residues are mutated, with higher PS content moderating this effect. TF/FVIIa was assembled on TF/liposomes with 5% PS (left) or 20% PS (right), then preincubated with varying XK1 concentrations. The residual TF/FVIIa enzymatic activity was quantified (normalized to the FX activation rate without XK1) and plotted vs XK1 concentration, from which IC50 values were derived (listed in supplemental Table 1). Individual data points are graphed in panels B-C (n ≥ 3). ∗∗∗P < .001. WT, wild-type.

This structure shows that the TF/FVIIa complex extends as a “mushroom-shaped” rod perpendicular to the nanodisc, with XK1 forming a “handle” contacting TF/FVIIa in 2 regions: the K1 domain of XK1 docked into the FVIIa active site, and extensive interactions of the FVIIa and XK1 GLA domains (and a portion of EGF1 domain of XK1) with the TF exosite region. The structure also reveals a previously unrecognized allosteric activation mechanism in which a loop on TF obscures access of the FX GLA domain until being displaced during formation of the TF/FVIIa/XK1/membrane complex. This work provides crucial structural evidence for understanding how TF/FVIIa interacts with its primary substrate on the membrane surface.

Methods

More detailed methods are provided in the supplemental Methods, available on the Blood website.

Recombinant proteins

Amino acid sequences and residue numbering of the recombinant proteins used in this study are given in supplemental Methods, as are details of their production. Recombinant, membrane-anchored TF consisted of TF residues 3 to 244, followed by a short linker and the Escherichia coli maltose-binding protein (MBP) sequence. For simplicity, this TF-MBP fusion protein is referred to as “TF” throughout the article, except in supplemental Figure 1A.

Assembly and evaluation of TF/FVIIa/XK1 complexes on nanodiscs

Nanodiscs with TF embedded in the bilayers (TF/nanodiscs) were assembled largely as described,32 with changes detailed in the supplemental Methods. Briefly, we used the truncated membrane scaffold protein, MSP1D1ΔH5,33 and the phospholipid composition was 50% phosphatidylserine (PS)/50% phosphatidylcholine (PC). TF/FVIIa/XK1 complexes for cryo-EM analyses were assembled by mixing TF/nanodiscs, FVIIa, and XK1 (with or without 10H10 Fab) in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 1.25 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.02% NaN3.

Cryo-EM data analysis

CryoSPARC was used for data processing with detailed steps outlined in the supplemental Methods.34

Movies were dose-weighted, motion corrected, and contrast transfer function–corrected to generate micrographs. Particles were picked in an unbiased approach using blob picker on a subset of 100 micrographs. All classes with nanodiscs were selected as templates. Selection of 2-dimansional (2D) classes with discernible signal protruding from the nanodiscs resulted in 479 810 particles. These were subjected to ab initio reconstruction with 3 distinct classes and heterogeneous refinement. The class containing well-resolved signal for the TF/FVIIa/XK1/10H10 complex was further refined using homogeneous refinement. A mask was used to subtract the nanodiscs from the particles. Two more rounds of 3D classification were used, including 1 with a filter mask around XK1 to classify based on the presence of XK1. The final 20 107 particles were refined with nonuniform refinement.

Refinement was also performed with the nanodisc included. The initial 2 140 190 particles were subjected to 2 rounds of ab initio reconstruction and heterogeneous refinement to eliminate junk particles. The class of particles belonging to a class with nanodisc and protein were subjected to homogeneous refinement followed by local refinement with a mask around the TF/FVIIa/XK1/10H10 complex. The resulting particles were subjected to 3D classification with a filter resolution of 12 Å and a focus mask around the protein complex. The best class of 91 001 particles was refined with nonuniform refinement resulting in a 3.2 Å resolution map. The distinct regions of the complex were segmented in ChimeraX and used for 3D Flexible Refinement in cryoSPARC with k = 2 latent dimensions with the segments corresponding to FVIIa/TF/10H10 kept rigid for mesh generation. The results confirm significant variability in the nanodisc and movement of the XK1 handle in the sagittal and frontal planes.

Results

Assembly and biochemical analysis of membrane-bound TF/FVIIa/XK1 complexes

To investigate how the membrane-bound TF/FVIIa complex interacts with FX, we assembled TF/FVIIa complexes on membrane nanodiscs for single-particle cryo-EM analysis. Because FX only transiently interacts with TF/FVIIa,35 we used the FX mimetic, XK1, to build a stable membrane complex. XK1 is a hybrid protein wherein the FX protease domain is replaced by the K1 domain of TFPI, which tightly binds into the FVIIa active site29 (Figure 1A). To further stabilize TF within nanodiscs during cryo-EM analysis, we created a TF fusion protein with MBP. We also added the Fab fragment of antibody 10H10 as an alignment fiducial to the complex. 10H10 binds TF but does not interfere with FVIIa binding or FX activation.30 We confirmed that TF/FVIIa complexes on nanodiscs robustly activated FX, irrespective of the presence of MBP or the 10H10 Fab (supplemental Figure 1A). 10H10 Fab had no effect on the ability of XK1 to inhibit TF/FVIIa enzymatic activity (supplemental Figure 1B).

As a FX mimetic, XK1 should interact with TF/FVIIa in a substrate-like manner.29 If so, then TF exosite mutations K165A and K166A5,6,9,11 should comparably reduce both the rate of FX activation by TF/FVIIa and the affinity of XK1 for TF/FVIIa. Indeed, the TF K165A and K166A mutations diminished FX activation by 16- to 59-fold, respectively, when TF/FVIIa was assembled on liposomes with 5% PS (Figure 1B; supplemental Table 1). Defects in FX activation rates were less pronounced when liposomes had 20% PS, consistent with reports that higher PS partially masks the severity of TF exosite mutations (Figure 1B; supplemental Table 1).5,15 Next, we assessed the ability of XK1 to inhibit TF/FVIIa complexes assembled on liposomes with 5% or 20% PS. As shown in Figure 1C and supplemental Table 1, the TF K165A and K166A mutations increased the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of XK1 (ie, diminished its efficacy) for inhibiting TF/FVIIa enzyme activity by 4.1- to 23-fold relative to wild-type TF, depending on mutation and PS content. This confirms our previous finding with TF exosite mutations and XK1,36 and is consistent with TF exosite mutations reducing the rate of inhibition of TF/FVIIa by TFPI in the presence of FXa.8 Taken together, this demonstrates that XK1’s interaction with TF/FVIIa relies on an intact TF exosite, paralleling the effects on FX activation.

Cryo-EM structure of membrane-bound TF/FVIIa/XK1 with and without 10H10

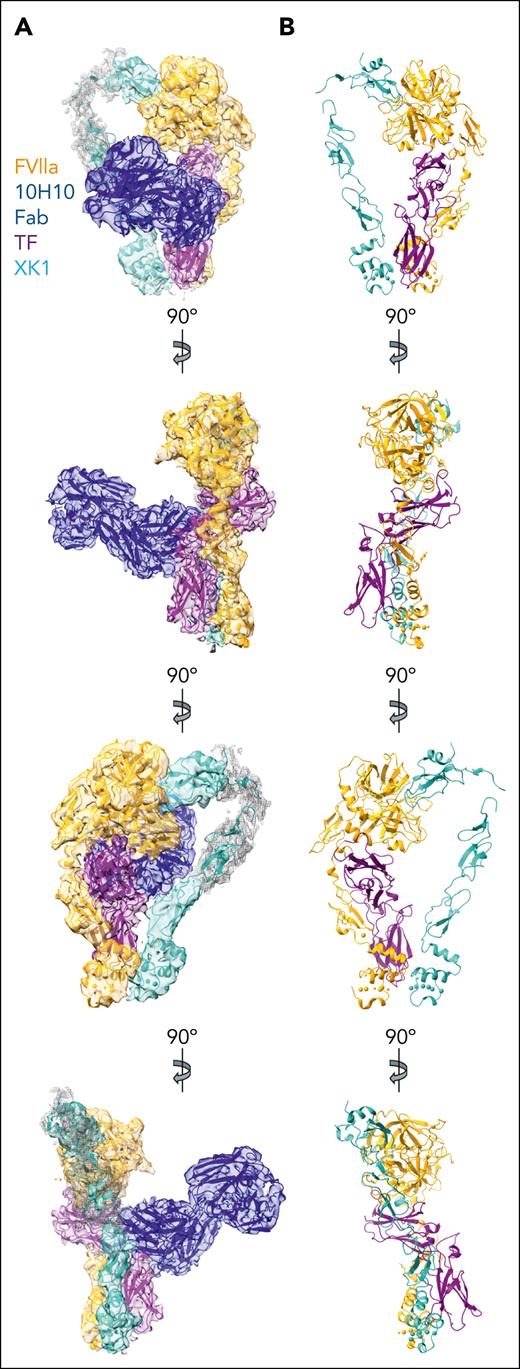

TF/FVIIa/XK1 complexes were then assembled on membrane nanodiscs, in the absence or presence of 10H10 Fab (supplemental Figure 2). The assemblies formed ordered protein complexes as evidenced by negative stain EM (supplemental Figure 2C-D,F). Using single-particle cryo-EM analysis, we determined the structure of the TF/FVIIa/XK1 complex assembled on a nanodisc and bound to a 10H10 Fab (Figure 2; supplemental Figures 3 and 4; supplemental Video 1). The structure has a resolution of 3.7 Å (loose mask); however, the local resolution across the EM density is not uniform (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 3C,E; supplemental Table 2). The quality of the EM density map allowed us to confidently identify the location of TF, FVIIa, XK1, and 10H10 Fab. The structure shows a mushroom-shaped density matching the available sTF/FVIIa crystal structures, with a thinner “handle-shaped” density, corresponding to XK1, interacting with the “stem” and “cap” of the mushroom (Figure 2A). There is clear density for the 10H10 Fab, bound to the “stem” of the of the mushroom, whereas the weaker density of the “handle” in both the 2D averages and 3D EM map suggests that this region of XK1 is structurally flexible, which was confirmed by 3D Flexible Refinement, indicating that there are continuous conformations in this region of XK1 (Figure 2A; supplemental Figures 3 and 5; supplemental Video 2).

Cryo-EM structure of the TF/FVIIa/XK1/10H10 complex. (A) Four views of the cryo-EM density map (at contour level of 0.1), together with the model of the TF/FVIIa/XK1/10H10 complex. The less structured portions of the XK1 density map (contour level of 0.04) are shown as a mesh, and the density for the nanodisc and MBP was subtracted for clarity. Views are rotated 90° around the y-axis. FVIIa, orange; TF, purple; XK1, light sea green; and 10H10 Fab, dark blue. (B) Views of the model of TF/FVIIa/XK1 complex, rotated 90° around the y-axis, with the same color scheme as in panel A. For clarity, the 10H10 Fab is not included in these views.

Cryo-EM structure of the TF/FVIIa/XK1/10H10 complex. (A) Four views of the cryo-EM density map (at contour level of 0.1), together with the model of the TF/FVIIa/XK1/10H10 complex. The less structured portions of the XK1 density map (contour level of 0.04) are shown as a mesh, and the density for the nanodisc and MBP was subtracted for clarity. Views are rotated 90° around the y-axis. FVIIa, orange; TF, purple; XK1, light sea green; and 10H10 Fab, dark blue. (B) Views of the model of TF/FVIIa/XK1 complex, rotated 90° around the y-axis, with the same color scheme as in panel A. For clarity, the 10H10 Fab is not included in these views.

The local resolution of most of the protein regions of the EM map was sufficient to model the peptide backbones and/or fit crystal structures into the density map to create an atomic model of the TF/FVIIa/XK1/10H10 complex associated with membrane (Figure 2; supplemental Figure 6A-B; supplemental Video 3). The structure of the 10H10 Fab fits easily into the EM density map (Figure 2A). Notably, the hinge between the Fab domains is at a different angle than was captured in the sTF/10H10 crystal structure (4M7L; supplemental Figure 6C). The best resolved region of the EM density map is the TF/FVIIa complex (supplemental Figure 3E,H), which closely matches the 1DAN crystal structure of sTF/FVIIa in the absence of membranes, except for the orientation of FVIIa GLA domain (supplemental Figure 6D). In the EM density map, this domain has shifted by ∼16° (supplemental Figure 6D). This structural change propagates through the FVIIa α-helix linking the GLA domain to the FVIIa EGF1 domain, resulting in a shift of the EGF1 domain relative to FVIIa GLA domain when compared with the crystal structures, as discussed in detail in “TF exosite interactions reveal a novel allosteric mechanism” (supplemental Figure 6D). Although there are no structures of full-length FX or XK1, crystal structures and homology models of their individual domains are available. The K1 domain of XK1 is also clearly resolved, allowing us to build a complete homology model in this region of the cryo-EM density (Figure 3). Placement of the crystal structure of the bovine FX GLA domain (1IOD) into the cryo-EM map was done using the clearly resolved FX α-helix (residues 34-43) that connects the GLA domain with the EGF1 domain. This α-helix allowed us to confidently orient a homology model of the human FX GLA domain into the map (Figures 2A and 3A; supplemental Figure 6E). Overall, the cryo-EM structure resembles the recent MD simulation of the TF/FVIIa/FX/membrane complex,28 although in that model the FX GLA and EGF1 domains are rotated ∼120° relative to the present structure (supplemental Figure 6E).

Protein-protein interactions between the FVIIa protease domain and the K1 domain of XK1. (A) Cryo-EM density map (shown as a mesh) and model of the TF/FVIIa/XK1 complex, with density for the 10H10 Fab, nanodisc, and MBP subtracted for clarity. Color scheme: FVIIa, orange; TF, purple; XK1, light sea green. Residues from 31 to 41 of the XK1 K1 domain, which form a hairpin-like conformation, are shown in dark red. The cryo-EM density map is shown at contour level 0.1, whereas the density for EGF2 is visible at higher contour levels. (B) View of the interaction between the protease domain of FVIIa and the K1 domain of XK1 with the density map at contour level 0.1. Boxes indicate areas of the structure magnified (C-D). Panels C-D show magnified views of specific regions of the FVIIa-XK1 interface boxed in panel B. Critical residues are shown as sticks and labeled, with carbon atoms colored according to the respective protein, oxygens in red, and nitrogen atoms in blue. Selected atomic distances are indicated with gray dotted lines. The backbones of G365 and G375 are shown in gray. The cryo-EM density in panels C-D is shown at contour level 0.13.

Protein-protein interactions between the FVIIa protease domain and the K1 domain of XK1. (A) Cryo-EM density map (shown as a mesh) and model of the TF/FVIIa/XK1 complex, with density for the 10H10 Fab, nanodisc, and MBP subtracted for clarity. Color scheme: FVIIa, orange; TF, purple; XK1, light sea green. Residues from 31 to 41 of the XK1 K1 domain, which form a hairpin-like conformation, are shown in dark red. The cryo-EM density map is shown at contour level 0.1, whereas the density for EGF2 is visible at higher contour levels. (B) View of the interaction between the protease domain of FVIIa and the K1 domain of XK1 with the density map at contour level 0.1. Boxes indicate areas of the structure magnified (C-D). Panels C-D show magnified views of specific regions of the FVIIa-XK1 interface boxed in panel B. Critical residues are shown as sticks and labeled, with carbon atoms colored according to the respective protein, oxygens in red, and nitrogen atoms in blue. Selected atomic distances are indicated with gray dotted lines. The backbones of G365 and G375 are shown in gray. The cryo-EM density in panels C-D is shown at contour level 0.13.

To ensure that the 10H10 Fab did not alter the overall structure of the TF/FVIIa/XK1/nanodisc complex, we also determined a lower resolution cryo-EM 3D structure without 10H10 (supplemental Figures 7-9; supplemental Video 4; supplemental Table 2). The mushroom-shaped TF/FVIIa density in the 2D averages contains detailed secondary structural elements, whereas the XK1 “handle” has a weaker signal, suggesting the same structural flexibility in this region of XK1 as seen in the presence of the 10H10 Fab (Figures 2A and 3A; supplemental Figure 9A). The resolution of the 3D map without 10H10 (supplemental Figures 7C-E and 9B) was not as high as the complex bound to the Fab, but the maps match well (supplemental Figure 9C) and the 3D model of TF/FVIIa/XK1 derived from the 10H10 Fab-bound map fits well into the non-Fab map with no significant domain shifts (supplemental Figure 9D). This confirms that 10H10 does not alter the orientation of the TF/FVIIa/XK1/nanodisc complex.

Key protein-protein interactions between XK1 and TF/FVIIa

The 3D EM structure and resulting atomic model of the TF/FVIIa/XK1/10H10 complex provide new insights into how TF/FVIIa interacts with substrate in the context of a membrane. The EM density map reveals that the substrate mimetic, XK1, interacts with TF/FVIIa through 2 main contact points and 1 minor one (Figure 3A). One major interaction occurs between the K1 domain of XK1 and the FVIIa protease domain (Figures 2B and 3B-D), which is explored in more detail in “Molecular basis of XK1 binding to the FVIIa active site.” In the minor contact, R200 at the upper end of the TF exosite is positioned to form a salt bridge with E51 in the EGF1 domain of XK1 (Figure 4B), consistent with reports for a role for FX’s EGF1 domain in substrate recognition by TF/FVIIa and formation of the TF/FVIIa/FXa/TFPI complex.13,37,38 We note that this residue is also a Glu at the equivalent position in FIX (the alternate substrate for TF/FVIIa), but is not conserved in other vitamin K–dependent clotting proteins (supplemental Figure 10). Near the membrane, the other major area of interaction occurs between the GLA domain of XK1, the TF exosite, and the FVIIa GLA domain (Figures 2B, 3A, and 4C-E). The rest of XK1’s 2 EGF domains make no discernable contact with TF/FVIIa, and much of this density is at lower resolution, consistent with flexibility. Such flexibility of the FX light chain is not inconsistent with the recent cryo-EM structure of the prothrombinase complex and of single-molecule fluorescence measurements of FXa,39,40 especially taken together with prior fluorescence resonance energy transfer studies estimating the distance of the FXa active site from the membrane surface.41

Key protein-protein interactions between the TF/FVIIa complex and the FX light chain portion of XK1. (A) The TF/FVIIa/XK1 cryo-EM density map, together with the atomic model, is repeated here from Figure 3A for orientation purposes. Color scheme: FVIIa, orange; TF, purple; and XK1, light sea green. (B) Close-up view of the interaction between TF residue R200 and FX residue E51 (in the EGF1 domain of XK1), shown with (left) and without (right) the cryo-EM density map. (C) Close-up view of the GLA domains of FVIIa and XK1 in proximity to the TF 4×Ser loop (indicated by purple arrow), shown with (left) and without (right) the cryo-EM density map. (D) Another close-up view highlighting interactions between the two GLA domains, and between the GLA domains and TF, shown with and without the density map. Interactions between TF residue K165, FVIIa residues γ35 and R36, and XK1 residue K45 are highlighted. (E) A close-up view (from a different angle relative to panels C-D), revealing interactions between the XK1 GLA domain and the TF exosite, shown with (left) and without (right) the cryo-EM density map. Interactions between XK1 residues γ14 and γ19 with TF residues K159, K166, and Y185 are highlighted.

Key protein-protein interactions between the TF/FVIIa complex and the FX light chain portion of XK1. (A) The TF/FVIIa/XK1 cryo-EM density map, together with the atomic model, is repeated here from Figure 3A for orientation purposes. Color scheme: FVIIa, orange; TF, purple; and XK1, light sea green. (B) Close-up view of the interaction between TF residue R200 and FX residue E51 (in the EGF1 domain of XK1), shown with (left) and without (right) the cryo-EM density map. (C) Close-up view of the GLA domains of FVIIa and XK1 in proximity to the TF 4×Ser loop (indicated by purple arrow), shown with (left) and without (right) the cryo-EM density map. (D) Another close-up view highlighting interactions between the two GLA domains, and between the GLA domains and TF, shown with and without the density map. Interactions between TF residue K165, FVIIa residues γ35 and R36, and XK1 residue K45 are highlighted. (E) A close-up view (from a different angle relative to panels C-D), revealing interactions between the XK1 GLA domain and the TF exosite, shown with (left) and without (right) the cryo-EM density map. Interactions between XK1 residues γ14 and γ19 with TF residues K159, K166, and Y185 are highlighted.

Molecular basis of XK1 binding to the FVIIa active site

Figure 3C-D shows that K1 residues 31 to 41 (10-20 in the numbering of bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor [BPTI]) adopt a hairpin-like conformation that inserts into the FVIIa active site, positioning itself near the active site triad of FVIIa (H193, D242, and S344; corresponding to H57c, D102c, and S195c in chymotrypsinogen numbering), as previously described for homologous Kunitz-type inhibitor/protease interactions.42,43 The P1 residue, K36 in K1, docks into the S1 pocket of FVIIa (Figure 3C).42,43 Kunitz domain residues D11, R20, and E46 (BPTI numbering) are thought to play key roles in determining TFPI domain specificity.42-45 In our model, K1 residue D32 (D11 in BPTI numbering) is in a position that would support interaction with FVIIa residues R290 (R147c) and K341 (K192c) (Figure 3C), consistent with K341 being reported to play a significant role in TFPI-mediated inhibition of the TF/FVIIa complex.8,46 K1 residue E67 (E46 in BPTI numbering) is positioned so that it could interact with FVIIa residues K197 and K199 (Figure 3D).42-44

TF exosite interactions reveal a novel allosteric mechanism

Previous biochemical data identified residues that comprise the TF exosite for FX activation (Y157, K159, S163, G164, K165, K166, and Y185), whose roles can now be examined in the context of our EM structure. The TF exosite clearly forms a connecting interface with the GLA domains of both FVIIa and XK1 (Figures 2B, 3A, and 4C-E). This binding interface includes TF residue K166, which is well positioned for electrostatic interactions with γ14 and γ19 in the XK1 GLA domain (Figure 4E). Furthermore, XK1 residue γ19 is positioned to form a salt bridge to TF residue K159 and a hydrogen bond with TF residue Y185 (Figure 4E). Despite its known importance for FX activation, TF residue Y157 does not interact directly with any XK1 or FVIIa residues but instead is positioned behind TF K166, possibly playing a structural role (Figure 4E). The region spanning the TF 4×Ser loop (S160-S163) and G164 lies at the interface between FVIIa and XK1 in the cryo-EM structure (Figure 4C). Although individual interactions between the side chains of residues in this region of the map cannot be fully resolved at the current resolution, the structure clearly shows this loop intercalating between the FVIIa and XK1 GLA domains (Figure 4C-E).

Aligning the cryo-EM structure of membrane-bound TF/FVIIa/XK1 to a crystal structure of sTF/FVIIa obtained without membranes (3TH2) reveals a few notable structural differences (Figure 5). In 3TH2, sTF residues S162, S163, and G164 sterically clash with the location of the XK1 GLA domain in the EM structure (particularly, with XK1 residues γ19 and γ20; Figure 5B-D). However, when looking just within the EM structure, there is no steric clash, and in fact the TF residues in the 4×Ser loop (and the backbone at G164) comprise part of the binding interface with the XK1 GLA domain, as described in the previous paragraph and shown in Figures 4C-E and 5E. Relative to the positions of sTF residues in the 3TH2 crystal structure, the TF 4×Ser loop and adjacent G164 residue in the cryo-EM structure are shifted about 4 Å toward the FVIIa GLA domain (shown with curved arrows in Figure 5A). Intriguingly, the backbone of FVIIa residue R36 (located in the α-helix that comprises the “aromatic stack” portion of the FVIIa GLA domain) is shifted in the same direction by ∼4 to 5 Å (Figure 5A,C). This movement positions the R36 side chain closer to TF residue K165 and primes γ35 of the FVIIa GLA domain to form a salt bridge with K45 of the XK1 GLA domain (Figures 4D and 5C). Additionally, this movement creates potential hydrogen bonding interactions involving TF residues S162 and S163, including: S162 hydroxyl with a γ20 carboxyl of XK1; S162 and S163 backbone carbonyls with the T21 hydroxyl in the XK1 GLA domain; and S163 hydroxyl with the backbone carbonyl of F31 in the FVIIa GLA domain (Figure 5E).

Novel allosteric regulation of the TF exosite revealed by comparing the cryo-EM structure of TF/FVIIa/XK1/10H10 with the sTF/FVIIa crystal structure (3TH2). (A) Superposition of 3TH2 crystal structure of sTF/FVIIa with the cryo-EM map and model of TF/FVIIa/XK1, aligned via their TF components. Insets highlight conformational differences in the FVIIa GLA domain (left box) and the TF 4×Ser loop (right box). The color scheme for the cryo-EM map (mesh) and model is as follows: FVIIa, orange; TF, purple; and XK1, light sea green. For the 3TH2 crystal structure, FVIIa is shown in light gray and sTF in black/dark gray. The map is contoured at 0.1. For clarity, the 10H10 density was subtracted from the cryo-EM map and omitted from the model. (B-E) In the close-up views, the map is contoured at 0.145, and key interacting residues are shown as sticks and labeled, with carbon atoms colored by molecule, nitrogen in blue, and oxygen in red. (B) Close-up view focusing on the FVIIa and XK1 GLA domains within the alignment of TF/FVIIa/XK1 (cryo-EM structure) with the 3TH2 crystal structure. Arrows indicate the 4×Ser loop. (C) Close-up comparison of the positions of residues R36 of FVIIa and K165 of TF in the cryo-EM structure vs the sTF/FVIIa crystal structure, with the 4×Ser loop indicated by arrows. (D) Close-up view of the TF 4×Ser loop (arrows) and the XK1 GLA domain in the alignment between the cryo-EM structure and the sTF/FVIIa crystal structure. Note that the 4×Ser loop in the sTF/FVIIa crystal structure (but not the cryo-EM structure) sterically clashes with the cryo-EM density map of the XK1 GLA domain. FVIIa was omitted in this view for clarity. (E) Another close-up view of the region including the TF 4×Ser loop (arrows), highlighting interactions between TF residues S162 and S163 with FVIIa residue F31 and XK1 residues γ20 and T21.

Novel allosteric regulation of the TF exosite revealed by comparing the cryo-EM structure of TF/FVIIa/XK1/10H10 with the sTF/FVIIa crystal structure (3TH2). (A) Superposition of 3TH2 crystal structure of sTF/FVIIa with the cryo-EM map and model of TF/FVIIa/XK1, aligned via their TF components. Insets highlight conformational differences in the FVIIa GLA domain (left box) and the TF 4×Ser loop (right box). The color scheme for the cryo-EM map (mesh) and model is as follows: FVIIa, orange; TF, purple; and XK1, light sea green. For the 3TH2 crystal structure, FVIIa is shown in light gray and sTF in black/dark gray. The map is contoured at 0.1. For clarity, the 10H10 density was subtracted from the cryo-EM map and omitted from the model. (B-E) In the close-up views, the map is contoured at 0.145, and key interacting residues are shown as sticks and labeled, with carbon atoms colored by molecule, nitrogen in blue, and oxygen in red. (B) Close-up view focusing on the FVIIa and XK1 GLA domains within the alignment of TF/FVIIa/XK1 (cryo-EM structure) with the 3TH2 crystal structure. Arrows indicate the 4×Ser loop. (C) Close-up comparison of the positions of residues R36 of FVIIa and K165 of TF in the cryo-EM structure vs the sTF/FVIIa crystal structure, with the 4×Ser loop indicated by arrows. (D) Close-up view of the TF 4×Ser loop (arrows) and the XK1 GLA domain in the alignment between the cryo-EM structure and the sTF/FVIIa crystal structure. Note that the 4×Ser loop in the sTF/FVIIa crystal structure (but not the cryo-EM structure) sterically clashes with the cryo-EM density map of the XK1 GLA domain. FVIIa was omitted in this view for clarity. (E) Another close-up view of the region including the TF 4×Ser loop (arrows), highlighting interactions between TF residues S162 and S163 with FVIIa residue F31 and XK1 residues γ20 and T21.

The significant rearrangement of the 4×Ser loop in this complex suggests an important role in facilitating the interaction between TF, FVIIa and FX. We propose that the FVIIa GLA domain exerts an allosteric effect which includes FVIIa residue R36 repelling TF residue K165, causing the adjacent loop (TF residues S160 to G164) to move aside to expose the binding interface for interacting with the XK1 GLA domain (Figure 5; supplemental Video 5).

Discussion

Our cryo-EM density maps of the TF/FVIIa/membrane complex show that this elongated complex is arranged perpendicular to the membrane surface, confirming prior fluorescence resonance energy transfer measurements.47,48 The high-affinity FX mimetic, XK1, was also bound to the complex, providing new insights into the structural basis of FX recognition by TF/FVIIa. Although XK1 is a surrogate for the natural substrate, FX, which could represent a potential limitation of this study, we demonstrated that its affinity for the membrane-bound TF/FVIIa complex depends on a functional TF exosite in the same way that FX requires this exosite for efficient activation by membrane-bound TF/FVIIa. These data add confidence that the interaction of XK1’s FX light chain with TF/FVIIa reflects the enzyme/substrate interactions within the TF/FVIIa/FX Michaelis complex.

We found 2 main contact points between XK1 and TF/FVIIa: (1) the K1 domain of XK1 docks into the FVIIa active site (designed to mimic FX bound to FVIIa within the Michaelis complex); and (2) the TF exosite near the membrane surface engages the GLA domains of both FVIIa and XK1. It was technically challenging to obtain a high-resolution structure of what are 2 elongated peripheral membrane proteins (FVIIa and XK1) with very small membrane footprints, bound to a small, elongated, single-pass membrane protein (TF), all projecting away from a supported nanoscale membrane. Incorporating the Fab fragment of 10H10 facilitated a higher-resolution structure, which in turn allowed identification of protein-protein and protein-membrane interactions in greater detail. 10H10 has been shown to have no effect on the rate FX activation by TF/FVIIa, which we confirmed. We also demonstrated that it had no effect of the affinity of XK1 for TF/FVIIa.

Much of the FX light chain (ie, most of EGF1 and all of EGF2) makes no discernable contact with TF/FVIIa, making this part of the complex flexible. This fits with the idea that FX must interact selectively with the TF/FVIIa complex, while at the same time, not bind so tightly that egress of the product, FXa, would be too slow. Our structure contrasts with most computational models of the TF/FVIIa/FX complex (typically in the absence of the membrane), which predicted extensive contact surfaces between TF/FVIIa and all FX domains.24-27 We previously reported that aligning these prior models with the sTF/10H10 crystal structure reveals extensive steric clash between FX and the 10H10 Fab,28,31 indicating that their trajectories for FX cannot be correct. In our more recent MD simulation of the TF/FVIIa/FX/membrane complex, FX interacts with TF/FVIIa in a manner that resembles that of XK1 in the membrane associated cryo-EM complex, in that both EGF domains of FX are in the solvent, projecting away from TF/FVIIa (and also avoiding the steric clash with 10H10).28 However, in that MD simulation, the FX GLA domain is rotated ∼120° compared to its arrangement in the EM structure, so it has a different face of the FX GLA domain interacting with TF/FVIIa, and also has a different trajectory for the neighboring EGF1 domain.

A surprise in the EM structure was the location and movement of TF’s 4×Ser loop and adjacent G164 and K165 residues. Residues S163, G164, and K165 are among those whose mutation to alanine defined the TF exosite.11 Although residues S160, S161, and S162 were not mutated in the original exosite studies, more recently we showed that any change in the length of TF’s 4×Ser loop—including deleting or inserting even 1 Ser—drastically reduces the rate of FX activation.36 This is in spite of the lack of electron density for this loop in almost all crystal structures (supplemental Figure 11), indicating it is surface-exposed and likely disordered. The cryo-EM structure now reveals that residue R36 in the FVIIa GLA domain, previously shown to be important in FX activation,16 is positioned near TF residue K165 in what appears to be a charge-charge repulsion. This is a consequence of the FVIIa GLA domain moving relative to its position in the sTF/FVIIa crystal structures, accompanied by upward movement of TF residue K165 shown in the view in Figure 5C, and movement of adjacent TF residue G164 and the entire 4×Ser loop toward FVIIa by some 4 to 5 Å (Figure 5C-E; supplemental Video 5). As a result, the EM structure shows that the FX GLA domain is now abutted up against TF residues S162, S163, and G164 in a location that clashes with these same TF residues in sTF/FVIIa crystal structures (Figure 5). The fact that this TF loop undergoes substantial movement relative to the crystal structures helps explain why none of the prior computational or docking models (including our own) predicted the correct placement of the FX GLA domain on the TF/FVIIa complex.

We now propose a novel allosteric activation mechanism for the TF exosite. When TF/FVIIa assembles on a membrane bilayer, the FVIIa GLA domain engages PS and becomes repositioned, resulting in FVIIa residue R36 repelling TF residue K165. This charge-charge repulsion, in turn, forces TF residues from S160 to G164 to move aside, uncovering a cryptic FX GLA domain binding site. This mechanism explains why reversing the charge of TF residue K165 (ie, the K165E mutation) tightens the FVIIa-TF binding affinity threefold while greatly decreasing FX activation.9,15 It also comports with the finding that mutating FVIIa residue R36 substantially decreases the rate of FX activation by TF/FVIIa,16 and agrees with a series of domain deletion and swapping studies that implicated the FVIIa and FX GLA domains as the likeliest interaction points with the TF exosite.9,13,16-18 It explains why changing the length of the 4×Ser loop by even 1 residue is so deleterious for FX activation, given that this loop must move aside and become part of the binding interface between the FVIIa and FX GLA domains. We propose that it is the engagement of the FVIIa and FX GLA domains with PS in the bilayer that drives these structural rearrangements. The dissociation constant (Kd) for binding of FVIIa to membrane-embedded TF drops from 2.7 nM when TF is embedded in pure PC membranes down to 41 pM when TF is in PC/PS membranes.17 Thus, engagement of PS with the FVIIa GLA domain contributes −10.4 kJ/mol to the binding energy (ΔΔG),17 which we propose drives allosteric activation of the TF exosite. This may also help explain why an elevated PS content can partially compensate for TF exosite mutations.

An extensive literature exists for the phenomenon of TF encryption/decryption.49 TF on the surface of unactivated, undamaged cells binds FVIIa with high affinity but poorly supports FX activation, whereas agents that induce the appearance of PS on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane are known to “decrypt” TF, resulting in full FX activation. Although other mechanisms have been proposed,50 the allostery uncovered in the present study provides a mechanistic explanation for understanding TF encryption/decryption on cell surfaces, in which the appearance of PS on the outer membrane leaflet repositions the FVIIa GLA domain to force the S160-K165 loop in TF to move aside. This then uncovers the previously cryptic binding site on TF for the FX GLA domain, permitting efficient recognition of FX as a substrate.

In conclusion, the cryo-EM structure of the TF/FVIIa/membrane complex bound to a high-affinity substrate mimetic provides crucial new structural insights into how the enzyme that triggers blood clotting in health and disease interacts with its primary substrate on the membrane surface. Unlike previous models—most of which lack a membrane context, a resolved TF 4×Ser loop, or a stably bound substrate—our structure captures key protein-membrane and protein-substrate interactions within a fully assembled complex (supplemental Figure 11). Finally, this 3D structure now allows us to propose a novel allosteric regulatory mechanism for the TF exosite region that explains a host of biochemical and mutational findings from the past 30 years, and the puzzling phenomenon of TF encryption/decryption.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Melanie P. Muller for her early MD modeling work, Xueyuan Peng for help with initial cryo-EM data collection, and the University of Michigan (UM) cryo-EM facility scientists for their technical support. The UM cryo-EM facility is supported by the UM Biosciences Initiative, the Beckman Foundation, and the Life Sciences Institute.

This study was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) as follows: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants R35 HL135823 and R35 HL171334 (J.H.M.); NIH Director’s Office grant S10OD030275 (M.D.O.); and National Institute for General Medical Sciences grant R24 GM145965 (E.T.). F.B. was supported by predoctoral fellowship N028347 from the American Heart Association.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Authorship

Contribution: J.C.S., F.B., M.A.C., E.T., M.D.O., and J.H.M. conceived the project; J.C.S. and F.B. designed the experiments, purified proteins, and prepared and analyzed samples for cryoelectron microscopy analysis; J.C.S., A.L.P., K.M., and S.K. collected and processed electron microscopy data; A.M., P.-C.W., and C.D. built atomic models; M.A.C., E.T., M.D.O., and J.H.M. acquired funding and supervised the research; and J.C.S., A.L.P., M.D.O., and J.H.M. wrote the manuscript, with contributions from F.B. and E.T.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: James H. Morrissey, Department of Biological Chemistry, University of Michigan Medical School, 4301B MSRB III, 1150 West Medical Center Dr, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-5606; email: jhmorris@umich.edu; and Melanie D. Ohi, University of Michigan Life Sciences Institute, Mary Sue Coleman Hall, 210 Washtenaw Ave, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2216; email: mohi@umich.edu.

References

Author notes

J.C.S. and A.L.P. contributed equally to this study.

Atomic coordinates and cryoelectron microscopy density maps have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank and the Electron Microscopy Data Bank with the following accession codes: 9P0X and EMD-71090 for the TF/FVIIa/XK1/10H10 complex with density for the nanodisc subtracted during refinement; EMD-71093 for the TF/FVIIa/XK1/10H10 complex with nanodisc density included; EMD-71095 for the TF/FVIIa/XK1/10H10 complex with nanodisc density analyzed by 3-dimensional flexible refinement; and EMD-71094 for the TF/FVIIa/XK1 complex (without 10H10) with nanodisc density included.

Additional data are available on request from the corresponding authors, James H. Morrissey (jhmorris@umich.edu) and Melanie D. Ohi (mohi@umich.edu).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal