TO THE EDITOR:

The recent point and counterpoint articles by Peggs1 and Moskowitz2 discuss the evolving role of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) for Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) after failure of autologous HCT in the era of highly active novel agents including brentuximab vedotin (BV) and the immune checkpoint inhibitors. Although a subset of HL patients may achieve durable remissions with BV after failure of autologous HCT, the majority of patients will relapse, and median progression-free survival (PFS) for patients who do not achieve a complete response (CR) with BV is only 6 to 7 months.3 Furthermore, recent trial results have led to adoption of BV in earlier treatment paradigms, including maintenance following autologous HCT per the AETHERA trial,4 and frontline therapy per the ECHELON-1 trial.5 The efficacy of BV at relapse in these settings is unknown. The immune checkpoint inhibitors, nivolumab and pembrolizumab, are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration after failure of autologous HCT and BV and are associated with high response rates, but longer follow-up is required to determine the durability of these responses.6,7 In a recent update of the CheckMate 205 trial, patients who progressed after nivolumab had poor outcomes with 1-year overall survival (OS) of 59%.8

In our experience, nonmyeloablative allogeneic HCT using total lymphoid irradiation and antithymocyte globulin (TLI-ATG) conditioning is an effective treatment strategy for HL after failure of autologous HCT with a very low risk of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and nonrelapse mortality (NRM) and excellent long-term OS. From 2003 to 2016, we performed allogeneic HCT using TLI-ATG conditioning for 33 HL patients who had failure of autologous HCT, including 14 patients who had received prior BV (Table 1). All patients provided informed consent in the accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were enrolled in transplant protocols approved by the Stanford University institutional review board. All patients were transplanted before the US Food and Drug Administration approval of the immune checkpoint inhibitors for relapsed or refractory HL. Median age at the time of transplantation was 28 years (range, 22-51 years). Fourteen patients had HLA-matched related, 10 had HLA-matched unrelated, and 9 had HLA-mismatched unrelated donors. Fourteen patients had a CR at the time of allogeneic HCT, 16 had a partial response, and 3 had SD or PD. Four patients received additional radiotherapy during TLI as a boost to sites of residual disease prior to transplantation.

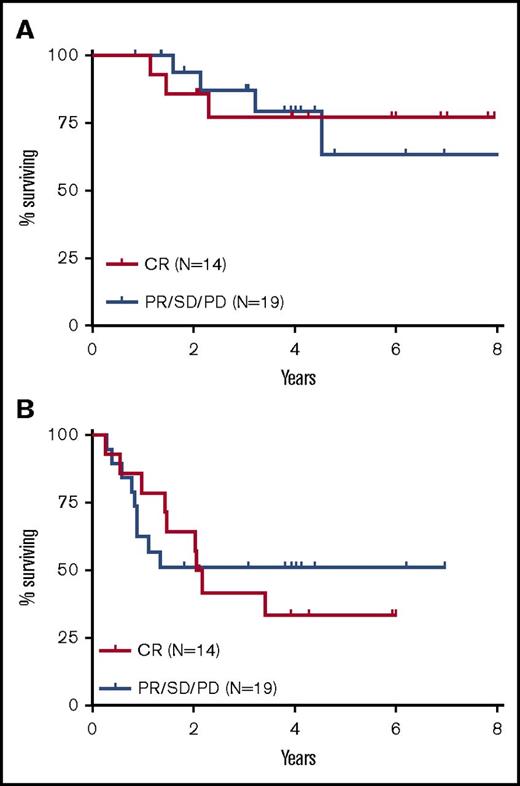

At a median follow-up of 4 years, the 4-year OS was 79% (8-year OS was 71%), and the 4-year PFS was 45% (Figure 1). Of the 16 patients who relapsed after allogeneic HCT, 6 were able to achieve a durable CR after treatment with additional chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and/or donor lymphocyte infusion, including 1 patient who received posttransplant nivolumab. The latter patient developed pneumonitis that resolved with corticosteroids but did not develop acute GVHD after treatment with nivolumab. At the last follow-up, 22 patients (67%) were alive in CR, 4 were alive with disease, and 7 were deceased. NRM was 0% at 1 year, with only 1 death from infection occurring 1.5 years posttransplant. The cumulative incidences of acute GVHD grade 2‐4 and grade 3‐4 at day +100 were 6% and 3%, respectively, and were consistently low regardless of donor type. The cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD (mild to moderate) was 27% at 1 year and 34% at 2 years. Durable remissions were seen even among patients with residual disease at the time of transplantation (Figure 2).

Outcomes after allogeneic transplantation with TLI-ATG conditioning. Kaplan-Meier and cumulative incidence curves show outcomes for 33 patients with Hodgkin lymphoma who underwent nonmyeloablative allogeneic transplantation with TLI-ATG conditioning after failure of autologous transplantation. (A) OS. (B) PFS. (C) Nonrelapse mortality. (D) Acute GVHD grade 2-4. (E) Acute GVHD grade 3-4. (F) Chronic GVHD.

Outcomes after allogeneic transplantation with TLI-ATG conditioning. Kaplan-Meier and cumulative incidence curves show outcomes for 33 patients with Hodgkin lymphoma who underwent nonmyeloablative allogeneic transplantation with TLI-ATG conditioning after failure of autologous transplantation. (A) OS. (B) PFS. (C) Nonrelapse mortality. (D) Acute GVHD grade 2-4. (E) Acute GVHD grade 3-4. (F) Chronic GVHD.

Outcomes stratified by disease status before transplantation. Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS (A) and PFS (B) are shown stratified by disease status before allogeneic transplantation. Fourteen patients had a CR at the time of allogeneic transplantation and 19 patients had a PR, SD, or PD.

Outcomes stratified by disease status before transplantation. Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS (A) and PFS (B) are shown stratified by disease status before allogeneic transplantation. Fourteen patients had a CR at the time of allogeneic transplantation and 19 patients had a PR, SD, or PD.

In summary, our data suggest that nonmyeloablative allogeneic HCT using TLI-ATG conditioning is an effective treatment strategy for HL after failure of autologous HCT, with excellent long-term OS exceeding 70% and a very low risk of NRM and GVHD. The low risk of NRM and GVHD was observed even among patients with a partially HLA-mismatched unrelated donor, which is consistent with our prior experience using TLI-ATG conditioning.9 Although it is certainly reasonable to first consider BV and the immune checkpoint inhibitors for HL patients who relapse after autologous HCT, our data lend strong support that appropriate patients should continue to be referred for transplant consultation because they may be effectively salvaged and achieve durable remissions with nonmyeloablative allogeneic HCT. It remains unclear whether the pretransplant use of immune checkpoint inhibitors may increase the risk for GVHD. Further studies are needed to determine whether a washout period should be implemented before proceeding with allogeneic HCT.10

Authorship

Contribution: M.A.S. wrote the paper; R.H.A., R.T.H., R.L., and L.S.M. revised the paper; and R.T.H. provided data on radiotherapy.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michael A. Spinner, Division of Oncology, Department of Medicine, Stanford University, 875 Blake Wilbur Dr, Stanford, CA 94305; e-mail: mspinner@stanford.edu.