TO THE EDITOR:

The stromal antigen 2 (STAG2) gene, located on chromosome Xq25, is a core component of the cohesin complex that functions on chromatin organization, transcriptional regulation, and postreplicative DNA repair.1-3STAG2 mutations (STAG2ms) are reported in 5% to 10% of myeloid neoplasms (MNs), mostly high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).4,5 Although few data are available on the frequency of STAG2ms alone, collectively, cohesin complex mutations are present in 8% of MDS, 12% of AML, and 10% of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia cases. It is considered 1 of 8 secondary-type mutations and are specific to secondary AML (sAML).6STAG2ms correlate with MDS response to hypomethylating agents (HMAs)3,5 but are linked to poor prognosis in MDS,3,7,8 with conflicting data on AML outcome8-11 and limited data on effects of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).

Our single-institute retrospective study included 91 patients with STAG2m MN, whose charts were reviewed for clinical information after institutional review board approval. Patients were included at date of in-house STAG2-harboring next-generation sequencing (NGS) (performed at diagnosis or progression). Diagnosis was rendered according to World Health Organization classification12,13 and MDS risk stratification according to the Revised International Prognostic Scoring System.14 BlueSky Software V7.40 was used for statistical analysis.

Most patients were older (median age, 72 years) males (78%). MDS was the most common diagnosis (55%), followed by AML (29%), MDS/myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) overlap, and MPN. Of the MDS cases, 36 (72%) belonged to the excess blast subtype (MDS-EB) (including 17 MDS-EB1 and 19 MDS-EB2) and 23 (46%) were high or very high risk. None were of the ring sideroblast subtype (including the 8 patients carrying SF3B1m). Ten patients with AML (38%) had sAML, whereas 14 patients (15%) had therapy-related MN (t-MN) (including 10 and 8 who received prior chemotherapy and radiotherapy, respectively). By the European LeukemiaNet risk stratification, 18 of the AML cases were adverse risk, 7 intermediate, and 1 favorable risk. Twenty-eight patients (31%) had abnormal cytogenetics, with trisomy 8 being the most common (Table 1; supplemental Tables 2-4). None of the females had X-chromosome deletion.

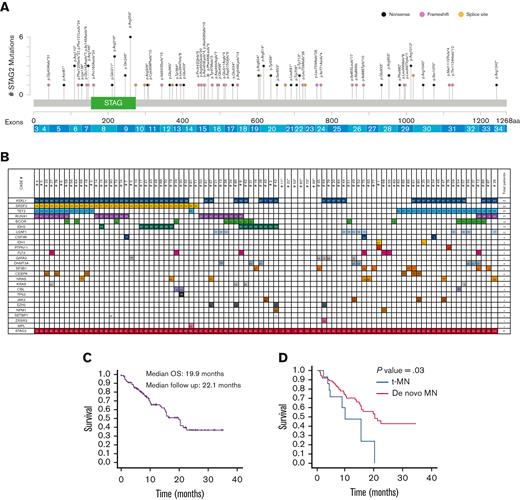

The median VAF of STAG2ms was 50% (range, 5% to 100%) and was significantly higher in males (P < .001), as expected of an X-linked gene. Corrected median VAF (accounting for X chromosome) was 29.5% and 27% in males and females (P = .5), respectively. There was no difference in VAF between diagnostic groups (P = .6), MDS subtypes (P = .7), high and non–high-risk MDS (P = .6), de novo AML (dnAML) (P = .2), and sAML or between t-MN and de novo MN (dnMN) (P = .1). There was no correlation between VAF and bone marrow (BM) or peripheral blasts. Most STAG2ms were in the N-terminus (64%) and 15 (16%) were in the STAG domain. Within the STAG domain, there were 6 (p.Arg259) and 4 (p.Arg216) nonsense mutations, representing mutational hotspots (Figure 1). Nonsense mutations were the most common (54%), followed by frameshift (36%) and splice site (10%) (supplemental Table 5). There was no correlation between mutation type or site and MN classification, BM blasts, or VAF.

STAG2m characteristics in patients with MN. (A) Representation of STAG2 variants detected, positioned on the STAG2 protein and its functional domains. The protein alterations are indicated on top of the corresponding mutation location, exon locations are indicated below the protein. (B) Comutational pattern in 91 patients with STAG2m MN. Each patient is represented by a column. The number reported in the box represents the VAF of each mutation. (C) OS for 88 patients with STAG2m MN. (D) OS for tMN vs dnMN in patients with STAG2m. STAG, STAG domain; aa, amino acid.

STAG2m characteristics in patients with MN. (A) Representation of STAG2 variants detected, positioned on the STAG2 protein and its functional domains. The protein alterations are indicated on top of the corresponding mutation location, exon locations are indicated below the protein. (B) Comutational pattern in 91 patients with STAG2m MN. Each patient is represented by a column. The number reported in the box represents the VAF of each mutation. (C) OS for 88 patients with STAG2m MN. (D) OS for tMN vs dnMN in patients with STAG2m. STAG, STAG domain; aa, amino acid.

The median number of comutations was 3 (range, 0-6) (supplemental Table 6). The most common were ASXL1 (65%), TET2 (36%), SRSF2 (36%), RUNX1 (30%), and BCOR (20%), whereas TP53 was uncommon (1%) (supplemental Figure 1; supplemental Tables 7 and 8). There was no correlation between the number of comutations and MN classification. Higher risk MDS had more BCOR mutations (P = .01) and RUNX1 mutations (P = .2) than lower risk MDS. There was no difference in the comutational pattern between dnAML and sAML or between dnMN and t-MN. t-MN cases carried fewer comutations than dnMN (2 vs 3, P = .02), whereas sAML cases and those that progressed to AML carried 4. No single comutation was associated with progression to AML and none of those that progressed carried KRAS mutations/NRAS mutations. Six cases (7%) had isolated STAG2ms, including 3 MDS, 2 AML, and 1 CCUS. There was no difference in VAF (P = .2), BM blasts (P = .5), or cytogenetics in them (P = .3) compared with those in the comutated cases.

Sixty-four patients (70%) received treatment, including 33 patients with MDS, 21 with AML, 6 with MDS/MPN, and 3 with MPN. Among these, 47 (73%) received HMA either alone or in combination with venetoclax (VEN), and 6 (10%) received intensive chemotherapy (IC). Those who received HMA and those who received HMA + VEN had response rates of 46% and 59%, respectively (P = .4) (Table 1). There was no difference in the response rate between those receiving HMA and those receiving IC (83%) (P = .2) or between those receiving HMA + VEN and those receiving IC (P = .3). Median overall survival (mOS) for HMA responders was not reached, and for HMA nonresponders, it was 20.4 months (P = .06). Twenty-five patients (28%) received HSCT including 11 with AML, 12 with MDS, and 2 with MDS/MPN. Before NGS, 3 patients had received HSCT. The median time from NGS to HSCT was 4.9 months.

Fifty-four percent and 19% of AML and MDS cases, respectively, relapsed after remission. There was no difference between those who received HMA and those who received IC (P = .6); and cytogenetics, VAF, and BM/peripheral blasts did not affect relapse. Nine MDS (18%) and 2 MDS/MPN (22%) cases progressed to AML. By competing risk analysis, time to progression in patients with MDS was 10.4 months. Median event-free survival for patients with MDS was 16.3 months. Higher risk MDS and those with higher BM blasts were more likely to progress (P = .04 and P = .008, respectively), whereas no other factors predicted progression.

mOS among 88 patients (after excluding CCUS and aplastic anemia) was 19.9 months (number of deaths = 39). Median 2-year survival in patients with AML was 40%. There was no difference in survival based on sex (P = .2) or cytogenetics (P = .08). There was no difference between diagnostic groups (P = .3), sAML and dnAML (P = .2), or higher and lower risk MDS (P = .6). Patients with t-MN had lower mOS than dnMN (9.9 vs 20.5 months, P = .03). Those with circulating blasts ≥5% had lower mOS than those with <5% (10.1 vs 21.4 months, P = .01). On univariate Cox regression analysis with VAF as a continuous variable, mOS worsened with increasing VAF (hazard ratio [HR], 1.01; P = .03). t-MN and circulating blasts ≥5% remained significant on multivariate analysis (supplemental Table 9), whereas higher VAF worsened OS (HR, 1.01; P = .09). A higher VAF worsened OS in males alone with HR, 1.01 and P = .1. Analysis of OS against corrected VAF among all patients yielded HR, 1.02 and P = .1. Patients who received HSCT after NGS had longer mOS than those who without HSCT (HR, 0.4; P = .06; by time-dependent variable analysis). Mutations of KRAS, PTPN11, and CBL led to lower mOS (P < .001, P < .001, and P = .04, respectively), whereas IDH2 mutations improved mOS (P = .04). Neither ASXL1 mutations nor comutational burden affected mOS (Figure 1; supplemental Figures 2-11).

Of 91 patients, 47 (52%) were diagnosed with MN before NGS (supplemental Figure 12), with a median time of 8.4 months from initial diagnosis to in-house NGS. Among 37 non-AML cases, 7 (19%) had progressed to AML at time of NGS. mOS did not differ between those with and without a prior diagnosis (P = .9). Thirty-one of 91 patients had a subsequent NGS (S-NGS). Sixteen patients (52%) continued to harbor STAG2m in S-NGS and had poor mOS compared with those who did not (19.9 months vs not reached, P = .03) (supplemental Figure 13). Where the STAG2m was lost on S-NGS, the median number of comutations became 2. Of 11 patients with AML who had a S-NGS, 7 had lost STAG2m. Four of these 7 patients had shown response to therapy, whereas the remaining 3 had not.

Our study included 91 patients, which is the largest cohort of patients with STAG2m MN in current literature. We found a high cooccurrence of STAG2ms and ASXL1 mutations, as previously alluded to by Kon et al.15,16 We demonstrated the prevalence of higher risk disease among patients with STAG2m MDS, as previously suggested.4,5 Eighteen percent of MDS cases progressed to sAML, with an increased comutational burden on progression, as previous studies suggest.17-19 It is possible that STAG2ms, therefore, favor transformation through induction of genetic instability and acquisition of new mutations. In our cohort, 31% patients had abnormal karyotype. Thota et al5 had found that the prevalence of abnormal karyotype was similar among cohesin-mutated and wild-type MN. Our study found that karyotype did not impact survival or disease progression, which previous studies had not alluded to.

Our study also showed STAG2ms to be associated with poor prognosis in MN. There was possible worsening of OS with higher VAF, which may be highlighted with a larger cohort. This, combined with the lack of association between MN classification and OS, suggests an adverse impact of STAG2ms on survival regardless of phenotypic features. There was also no correlation of VAF with clinical features (age, MN phenotype, and blast counts); hence, there was no clear explanation for an impact of VAF. Because none of the females had X-chromosome deletion, the impact of the loss-of-heterogeneity could not be assessed. STAG2m sAML had comparable clinical characteristics and survival to dnAML, unlike what others have suggested.20 This supports the notion that STAG2ms are secondary type and define a subset of dnAML cases with worse clinical outcome, comparable to that of clinically defined sAML.6 Our data also suggest a positive response to HSCT among patients with STAG2m MN, albeit a larger sample size is needed to confirm this.

Our study is limited by the relatively small sample size, retrospective nature, patient heterogeneity, and the lack of long-term follow-up. To our knowledge, we present novel findings on the role of STAG2ms in MN progression. A larger cohort can provide further insight.

Contribution: B.K., A.N., and A.A.-K. planned the study, reviewed data, completed statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript; R.H. and D.V. performed molecular analysis and reviewed the manuscript; P.N. reviewed BM slides and manuscript; P.G. performed cytogenetic analysis and reviewed the analysis; K. Bessonen coordinated NGS data collection; and N.G., K. Begna, A.T., A.M., M.P., W.J.H., M.L., M.V.S., C.A.Y., J.F., T.B., and H.B.A. reviewed the manuscript and contributed patients.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Aref Al-Kali, Division of Hematology, Mayo Clinic, 200 First St SW, Rochester, MN 55905; e-mail: alkali.aref@mayo.edu.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Aref Al-Kali (alkali.aref@mayo.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.