Key Points

Brentuximab vedotin addition du gemcitabine safely increases treatment efficacy in patients with relapsed and refractory PTCL.

Baseline soluble CD30 appears strongly predictive of outcome whereas CD30 expression is not, specially in patients with TFHL and PTCL-NOS.

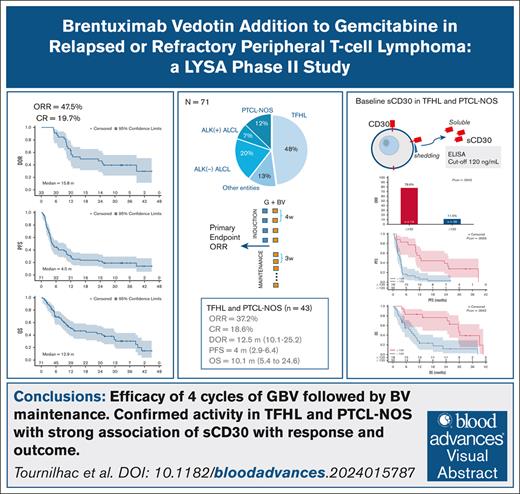

Visual Abstract

We aim to evaluate the efficacy of brentuximab vedotin (BV) combined with gemcitabine (GBV) followed by BV maintenance in relapsed or refractory (R/R) peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL). Patients with at least 5% CD30+ cells by immunohistochemistry received 4 GBV induction (28 days) cycles of gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 (day 1, day 15) plus BV 1.8 mg/kg (day 8) followed, in responding patients, by up to 12 BV maintenance (21 day) cycles. Primary end point was overall response rate (ORR) after 4 induction cycles by computed tomography scan–based Lugano criteria. Of 71 enrolled patients (median age of 66 years), 80.3% had received 1 previous line and 60.6% were refractory. The diagnoses per pathology central review were follicular helper T-cell lymphomas (TFHL; 47.9%), anaplastic large-cell lymphomas (ALCL; anaplastic lymphoma kinase [ALK] negative [19.7%] and ALK+ [7%]), peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS; 12.7%), and other entities (12.7%). In the intention-to-treat analysis, ORR was 46.5%, with 19.7% complete response. Twenty-eight patients received maintenance. Grade 3 to 4 adverse events reported in ≥10% of patients during induction comprised neutropenia (55%), thrombocytopenia (14%), anemia (21%), and infection (14%); during maintenance comprised neutropenia (39%), thrombocytopenia (21%), and peripheral neuropathy (14%). With a median follow-up of 32.6 months, the median duration of response, progression-free, and overall survival were 15.8, 4.5, and 12.9 months, respectively. Efficacy, higher in ALCL, was present in the TFHL and PTCL-NOS group. A negative association of high baseline soluble CD30 on both response and survival was found, which, in ad hoc analysis, appeared highly relevant in patients with TFHL and PTCL-NOS. This trial was registered at the European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials database as #2017-000409-1, and at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT03496779.

Introduction

Peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs) are a heterogeneous group representing 6.3% of noncutaneous lymphomas, including angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL; the major subtype of the follicular helper T-cell lymphomas [TFHL] subgroup); PTCL not otherwise specified (PTCL, NOS); and anaplastic large cell lymphomas (ALCL), anaplastic lymphoma kinase positive [ALK+] or ALK−.1

Patients with relapsed or refractory (R/R) PTCL have a poor prognosis, with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of ∼3 months and a median overall survival (OS) of 5 to 11 months in patients unable to reach transplant consolidation.2-6 The most consistent curative approach remains allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT).7,8 Only a small proportion of patients are eligible, and allo-HCT should, at best, be offered to patients with controlled disease. Treatment options after failing first-line therapy are limited, stressing the need for novel therapeutic agents. Numerous regimens are currently being used, with no evidence that multidrug combinations are more effective than monotherapies.9,10

Brentuximab vedotin (BV), an anti-CD30 chimeric monoclonal antibody coupled to the microtubule-disrupting monomethyl auristatin E, has shown spectacular efficacy in the treatment of R/R ALCL (both ALK− and ALK+), with an overall response rate (ORR) of 86%, including 57% complete response (CR), and 25.6 months median duration of response (DOR).11,12 Data pertaining to BV monotherapy in relapse treatment of non-ALCL entities that may express CD30 were reported in prospective phase 2 studies with lower ORR and CR rates of 25% to 45% and 10% to 25%, respectively.13-15 In non-ALCL entities, the factors predictive of response are undetermined and appear unrelated to the level of CD30 expression in the tumor.13,14,16

The French Lymphoma Study Association (LYSA) group designed a prospective phase 2 study to assess the efficacy and tolerability of an induction treatment associating BV with gemcitabine, a chemotherapy usually used as reference arm in controlled trial,17 followed in responders by BV maintenance in patient with CD30+ R/R PTCL.

Patients and methods

Study design and participants

This LYSA prospective open-label phase 2 study was conducted in 31 centers in France and in 8 centers in Belgium (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03496779). Patient recruitment took place between 10 April 2018 and 8 October 2019, with the last patient visit on 25 August 2022 and a cutoff date of October 2022.

Patients aged 18 to 80 years with histologically proven PTCL; CD30+ (at least 5% of cells according to local examination of the most recent available biopsy); relapsing after, or refractory to, ≥1 line but ≤3 previous lines of therapy; and at least 1 nodal or extranodal target lesion of ≥1.5 cm were eligible.

Main exclusion criteria were central nervous system involvement, neutrophil count of <1.5 × 109/L, platelet count of <75 × 109/L, hemoglobin of <8 g/dL, creatinine of >2.0 mg/dL, or creatinine clearance of <40 mL/min. All criteria are listed in the online version of the protocol.

Study treatment

Patients were to receive 4 BV combined with gemcitabine (GBV) induction cycles every 28 days comprising gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 IV on day 1 and day 15, combined with BV 1.8 mg/kg IV on day 8. Patients achieving CR or partial remission (PR) after 4 induction cycles were started on maintenance with BV 1.8 mg/kg once every 21 days, up to a maximum of 12 cycles. After the end of induction, eligible patients could also stop BV maintenance and proceed to consolidation by autologous HCT (auto-HCT) or allo-HCT at their physician's discretion (supplemental Figure 1). Administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and antibiotic prophylaxis were left to the physicians’ discretion. In the event of peripheral neuropathy, as soon as grade ≥2 adverse events (AEs), according to the National Cancer Institute's Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.03), were observed, rules for treatment suspension, dose adjustment, or even discontinuation were applied.

Study assessments

Pretherapeutic evaluation included collection of data on disease-related symptoms; clinical examination; blood sampling; bone marrow trephine biopsy; and cervical, thoracic abdominal, and pelvic computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET) scan. The primary end point was ORR after the fourth induction cycle in application of the revised Lugano 2014 criteria based on investigators' assessment of clinical and CT scan response.18 PET-CT assessment at fourth cycles was a secondary objective. Additional assessments were scheduled after the second induction cycle, after every 3 maintenance cycles, and at the end of maintenance, whether complete (12 cycles) or prematurely interrupted. Follow-up was then performed every 3 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months until at least 3 years after the last inclusion. The safety assessment consisted of collecting and grading AEs using the criteria of National Cancer Institute's Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.03.

Pathological review and exploratory analysis of CD30-associated parameters

Patient biopsies were collected at the LYSA Pathology Laboratory, Henri Mondor University Hospital, Créteil, France. Review of diagnoses according to the 2017 World Health Organization (WHO) classification19 and assessment of CD30 expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC; Ber-H2 clone; Dako, Agilent Technologies) on the most recent tumor samples available before inclusion were performed by 2 expert pathologists (L.d.L. and P.G.). The percentages of CD30+ cells in neoplastic cells and among all tumor cells (neoplastic cells and reactive microenvironment), were evaluated and recorded with 5% increments based on an adaptation of a previous work.20 Soluble serum CD30 (sCD30) was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (CD30 human enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit [Thermo Fisher, Asnieres, France], from frozen [−80°C], collected at baseline, according to product instruction). An initial screening dose was carried out by diluting the sera to 1 in 4, then dilutions to 1 in 10 or 1 in 100 were carried out, if necessary, to remain within the calibration range. Both central IHC assessment of CD30 expression and sCD30 and assays were performed blinded to the study investigators.

Statistical procedures

Sample size calculation was based on the primary end point (ORR) at the end of 4 induction cycles on the full analysis set corresponding to all patients receiving at least 1 dose of study treatment. To provide an 80% power to detect an increase of 15% of the ORR with 1-sided α of .05, a total of 70 patients was required. The null hypothesis was ORR of ≤35% according to the gemcitabine monotherapy arm of the Lumiere study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01482962).21 Patients without response assessment (due to any reason) are considered as nonresponders. Response rates are expressed with 90% confidence interval (CI) according to the Pearson-Clopper method. Logistic regression models were used to estimate the odd ratios (with 90% CIs) of prognostic factors. Time-to-event analysis were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method and are defined as the time from inclusion to event. Patients without an event are censored at the time of last visit with adequate assessment (or last contact for OS). For patients who underwent allo-HCT or auto-HCT consolidation, follow-up was censored at the date of transplantation. Time-to-event end points in the different groups were compared with the use of 2-sided log-rank tests and Cox proportional-hazards regression. Two different approaches, X-Tile22 and receiver operating characteristic analysis were used to define the optimal cutoff with minimal P value of CD30-associated parameters for prediction. Cutoff for survival data was determined with the X-Tile software, allowing the division of the population into subsets for the marker analyzed and to calculate log-rank P value at each cutoff point. The minimal P value is then selected as the optimal cutoff point. Cutoff for response rate were determined with receiver operating characteristic curves to optimize the sensibility and specificity with the use of the Youden index. Analyses were done with SAS software (version 9.3 or later), and X-Tile (version 3.6.1).

Considering the analysis of sCD30 and CD30 expression association with response and outcome, we used an approach adjusted for multiple comparisons according to the Miller and Siegmund method.23,24

The protocol for this study was approved by an independent ethics committee (30 January 2018 and 8 May 2018 for France and Belgium, respectively), and informed consent was obtained from each patient before any study-related procedure, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Patient characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the 71 patients enrolled and treated are shown in Table 1. Median age was 66 years, 66% were male and most had stage III to IV lymphoma (91.6%). Median time from PTCL diagnosis to inclusion was 9.4 months. Centrally reviewed histology according 2017 WHO classification was TFHL (47.9%; including AITL [38%] and nodal TFHL [9.9%]), followed by ALCL (including ALK+ [19.7%] or ALK− [7%]), PTCL-NOS (12.7%), and all other entities (12.7%). All patients had been exposed to CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, Oncovin [vincristine], and prednisone)/CHOP-like, 15.5% had received auto-HCT, 80.3% were on second-line therapy, and 60.6% were refractory to their previous line of therapy.

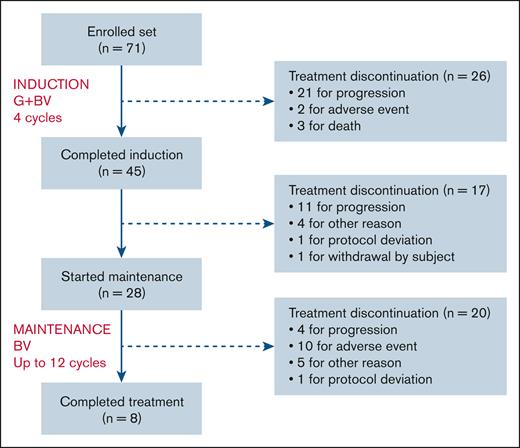

CONSORT diagram is in Figure 1. Forty-five patients completed 4 GBV induction cycles and 28 patients started BV maintenance, 8 of whom reached 12 maintenance cycles. Premature discontinuation was recorded in 63 patients, mostly from lymphoma progression (n = 36) followed by death or AEs (n = 15). There were 3 study withdrawals related to study deviation or patient request. Finally, 9 eligible patients were withdrawn to enable entry into a transplantation program as permitted by protocol after initial evaluation, either before (n = 4) or during maintenance (n = 5). Eventually, 5 underwent allo-HCT (including 1 after relapse and a short course of further treatment) and 1 auto-HCT followed by BV maintenance (supplemental Figure 2).

CONSORT diagram. Protocol deviations were: in 1 patient, the administration of a fifth BV induction cycle before a consolidation with auto-HCT; and 1 patient, the absence of a 12th cycle of maintenance. “Other reason” means patients withdrawn for transplantation program as permitted by protocol after initial evaluation, either before (n = 4) or during maintenance (n = 5).

CONSORT diagram. Protocol deviations were: in 1 patient, the administration of a fifth BV induction cycle before a consolidation with auto-HCT; and 1 patient, the absence of a 12th cycle of maintenance. “Other reason” means patients withdrawn for transplantation program as permitted by protocol after initial evaluation, either before (n = 4) or during maintenance (n = 5).

Efficacy

We ran intention-to-treat response evaluation of the full analysis set (n = 71) at end of induction. ORR was of 46.5% (90% CI, 36.30-56.89), with a CR and PR rate of 19.7% (90% CI, 12.33-29.10) and 26.7% (90% CI, 18.29-36.75), respectively. Hence, the lower limit of the 90% CI being above the 35% (null hypothesis), this phase 2 study provides a positive result according to our statistical plan. At 2 GBV cycles (n = 33), ORR was 49.3% (90% CI, 39.00-59.63) and CR rate was 12.7% (90% CI, 6.78-21.08). The best ORR was 55%, with CR and PR of 26.8% (90% CI, 18.29-36.75) and 28.2% [90% CI, 19.51-38.24), respectively, and in 66 evaluated patients for this criterion, the median time to best response was 3.5 (95% CI, 0.7-12.0) months.

Applying PET-CT, the overall metabolic response rate after 4 GBV cycles was (n = 32) 45.1% (90% CI, 34.96-55.50), including 23.9% complete metabolic response (Table 2).

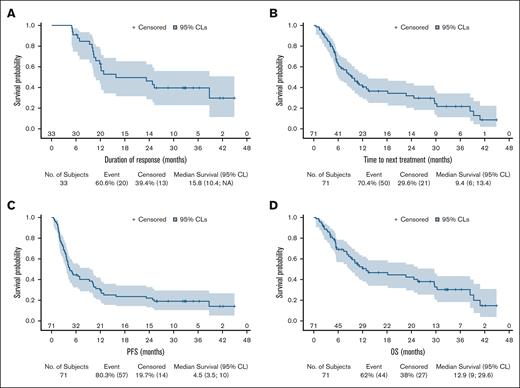

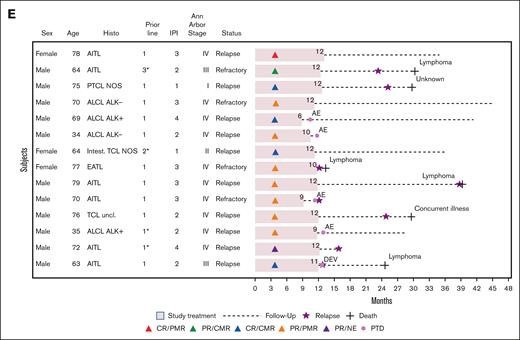

After a median follow-up of 32.6 months (range, 0.5-45), the median DOR, PFS, time to next treatment, and OS were 15.8 months (95% CI, 10.4 to nonapplicable), 4.5 months (95% CI, 3.5-10.0), 9.4 months (95% CI, 6.0-13.4), and 12.9 months (95% CI, 9.0-29.6), respectively (Figure 2A-D). The description of 14 patients with long-term responding PTCL with at least 12 months without disease progression is reported in Figure 2E.

The analysis of efficacy according to PTCL entities is reported in supplemental Table 1A-B and supplemental Figure 4.

CD30-associated parameter evaluation

Secondary end point included the analysis of CD30-associated parameters. CD30 expression by IHC was centrally evaluated in 63 patients on biopsies taken either at relapse before inclusion (n = 25), at diagnosis (n = 35), or at a previous relapse (n = 3). In ALCL, CD30 expression in neoplastic cells was constant, with a median of 92.5% positive cells. In the non-ALCL entities, the percentage of CD30+ neoplastic cells was lower, with a median of 10.0% in TFHL, 25.0% in PTCL-NOS, and 52.5% in other entities (supplemental Table 2). In 3 patients with TFHL with <5% CD30+ neoplastic cells, CD30 was found expressed at 5% within the tumor, including nonneoplastic cells.

For 65 patients with sCD30 available at baseline, the median level was 308 ng/mL (range, 21-9136; supplemental Table 3). We examined the potential interactions between the levels of sCD30 or CD30 expression with other covariates. Applying the cutoff of 10% (see hereafter) the percentage CD30 expression on neoplastic cells was not associated with any clinical variable except, unsurprisingly, with histology, because this percentage is much higher in ALCL than in the other subtypes. Applying the cutoff of 120 ng/mL (see hereafter), high sCD30 was associated with stage III to IV disease and intermediate or high International Prognostic Index but not with histology, although sCD30 levels were higher in patients with ALCL (supplemental Table 4A-B). We failed to demonstrate any correlation between baseline sCD30 and the percentage of CD30+ neoplastic cells either in the ALCL (P = .27) or in the non-ALCL (P = .48) groups.

Prognostic parameters

According to a prespecified univariate analysis we explored the prognostic value of baseline characteristics including CD30-related parameters. Baseline sCD30 was predictive of ORR, with an optimal cutoff level of 120 ng/mL (supplemental Figure 3). Conversely, no relevant cutoff was found for the percentage of CD30+ neoplastic cells by IHC. Therefore, based on previous reports16 and on Echelon-2 trial inclusion criteria,25 we applied the 10% cutoff of CD30+ neoplastic cells for further analysis.

This univariate analysis included 11 variables. An increased lactate dehydrogenase level was associated with a lower ORR (P = .008) and a CR rate (P = .044). Refractory status was associated with shorter PFS (P = .031) and OS (P = .007). Non-ALCL histology was associated with both shorter PFS (P = .049) and OS (P = .041). Strikingly, although CD30 expression of ≥10% had no impact, a high sCD30 of >120 ng/mL negatively influenced ORR (P = .0004), CR (P = .0057), PFS (P = .0114), and OS (P = .0196; supplemental Table 5).

We performed an exploratory ad hoc multivariate model including variables found to have significant impact in prespecified univariate analysis and 1 additional variable of clinical relevance (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of ≥2). ALCL histology and a low sCD30 level appeared in this model to have an independent positive impact on OS, PFS, and ORR. For CR, only sCD30 had an impact in this analysis (Table 3).

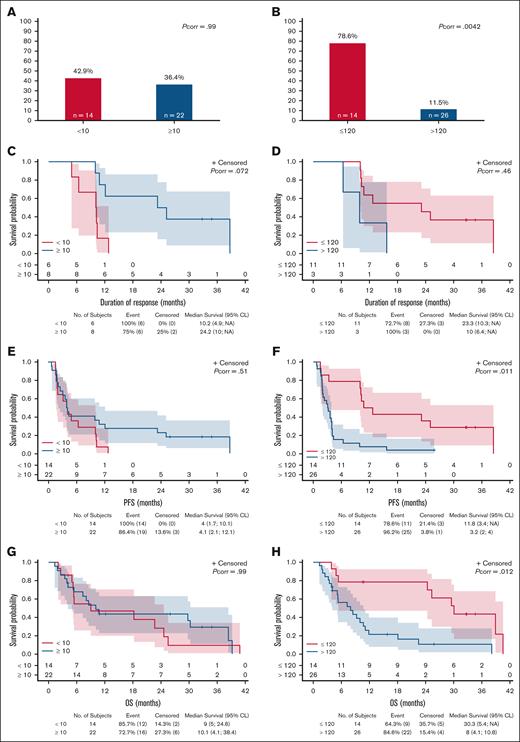

We finally performed another exploratory ad hoc analysis focusing on patients with TFHL and PTCL-NOS, having shorter PFS and OS and spanning a wide range of both percentage of CD30+ and baseline sCD30. In this group, we confirmed the very high negative impact of baseline sCD30 of >120 ng/mL and the absence of impact of CD30 expression on neoplastic cells of ≥10% on ORR, PFS, and OS (Figure 3). As a continuous variable, the percentage of CD30+ neoplastic cells also had no impact, whereas baseline sCD30 remained significantly associated with ORR (P = .012), CR (P = .038), and PFS (P = .043), but less with OS (P = .052), and not with DOR (P = .10).

Reponse and outcome according to CD30-associated parameters in TFHL and PTCL-NOS (exploratory analysis). ORR (A-B) and Kaplan-Meier estimate, with number of patients at risk and 95% CL of DOR (C-D), PFS (E-F), and OS (G-H) with relative impact of IHC CD30 expression on neoplastic cells (<10% vs ≥10%; left panels) and of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay baseline sCD30 level (≤120 ng/mL vs >120 ng/mL; right panels). NA, not applicable; Pcorr, corrected P-value.

Reponse and outcome according to CD30-associated parameters in TFHL and PTCL-NOS (exploratory analysis). ORR (A-B) and Kaplan-Meier estimate, with number of patients at risk and 95% CL of DOR (C-D), PFS (E-F), and OS (G-H) with relative impact of IHC CD30 expression on neoplastic cells (<10% vs ≥10%; left panels) and of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay baseline sCD30 level (≤120 ng/mL vs >120 ng/mL; right panels). NA, not applicable; Pcorr, corrected P-value.

Safety

During induction, patients were exposed to 236 cycles of GBV (mean, 3.3 [±1.01] cycles per patient) delivered over a mean of 2.7 (±1.01) months. A dose reduction of BV and gemcitabine was applied for 28 (39.4%) and 26 (36.6%) patients, respectively, and treatment was discontinued due to AEs in 2 patients.

During maintenance, 28 patients were exposed to 219 cycles of BV; mean 7.8 (±4.07) cycles per patient (range, 1-12) delivered over a mean of 5.0 (±2.98) months. BV dose reduction was applied in 16 (57.1%) patients and treatment was discontinued due to AEs in 10 patients.

At least 1 grade ≥3 AE was reported in 13 patients during induction and in 17 patients during maintenance. Grade 3 and 4 AEs are reported in Table 4.

Peripheral neuropathy of any grade, assessed as an AE of clinical interest, was reported in 22 patients during induction (n = 9 [12.6%]) or during maintenance (n = 13 [46.4%]), including grade 1 (n = 2), 2 (n = 13), or 3 (n = 7). In 7 patients, grade 3 (n = 5) or 2 (n = 2) peripheral neuropathies led to treatment discontinuation.

During the study, 44 deaths were reported, including 31 related to lymphoma, with a median time from inclusion to death of 7.7 (range, 0.53-40.87) and 5.6 (range, 1.31-39.26) months, respectively. In 13 cases, death resulted from concurrent illness (n = 9; including sepsis [n = 5], sudden death [n = 1], pneumonitis [n = 1], respiratory distress [n = 1], altered general condition [n = 1], and COVID-19 [n = 1]), toxicity of subsequent reinduction therapy (n = 1), or unknown (n = 3; supplemental Table 6). Five deaths from concurrent illness were reported as AEs occurring during induction; no grade ≥3 neutropenia was recorded during the GBV cycles in these patients and the investigator’s narrative did not describe that death resulted from neutropenia.

Discussion

In R/R PTCLs the development of new strategies is imperative and, following this aim, the LYSA group tested a regimen comprising GBV induction followed by BV maintenance. We obtained an ORR of 46.5%, significantly higher than a published experience of gemcitabine alone,17 with almost 20% CR and a DOR exceeding 15 months, which is achieved according to statistical plan, in comparison with gemcitabine alone. The cohort was well characterized based on central pathological review according to WHO 2017 classification. In univariate analysis, the treatment had more efficacy in patients with relapsed than in those with refractory disease and with ALCL, consistent with the knowledge that BV-based therapy is most beneficial in ALCL either in the R/R setting 12,13,26,27 or as frontline therapy.25

Despite being in line with our hypothesis, the benefit of combining BV with gemcitabine in comparison with gemcitabine alone remains modest. This study does not address the comparison of combining gemcitabine with BV compared with BV alone and does not provide statistically backed result for each PTCL entity, a frequent pitfall in PTCL studies.

The inclusion of ALCL may have led to an upward bias in the results. At time of study conception, BV was registered in R/R ALCL, based on the compelling results of a single pivotal phase 2 monotherapy study.11,12 Additional prospective data seemed useful. Moreover, given the possible inaccuracies of histopathological diagnosis,1 the probability of including CD30+ PTCL that would have turned out to be ALCL after review was significant. We finally based our statistical hypothesis on the gemcitabine arm of the Lumiere trial in which ALCL could be included.17,21 Surprisingly, in ALCL compared with the pivotal phase 2, ORR and CR rate appear lower with a shorter PFS, which, however, was censored in the event of transplantation. The changes in BV administration related to AEs were identical. The use of a combination at the expense of a reduction in the dose intensity of BV therefore does not appear to explain this difference. In addition, real life data of BV in ALCL28-31 have not always replicated the results of the pivotal phase 2 study and in the Echelon-2 trial update,26 ALCL patients who experienced progression after CHOP and received BV alone or in combination had 51% ORR and 39% CR rate.

For the non-ALCL entities, experience on BV monotherapy had been initially collected in 3 prospective studies13-15 of 35, 21, and 16 patients, the first being before the official classification identifying the major TFHL entity. Our study brings additional data in 34 patients with TFHL and 9 patients with PTCL-NOS. In this group as whole, the ORR and CR rate are 37.2% and 18.6%, respectively, the PFS and DOR are 4 (95% CI, 2.9-6.4) and 12.5 (95% CI, 10.1-25.2) months, respectively, and 7 patients remained free of progression for at least 12 months. Compared with gemcitabine monotherapy, ORR and CR rate at 4 cycles of the GBV combination was in the same range than in 2 prospective studies (ORR of 55% and 30%; CR of 35% and 22%; respectively).21,32 Likewise, if we consider the prospective results on BV monotherapy,13-15 our study does not show that combining gemcitabine with BV brings better results but confirms the level of activity of a BV-based strategy in patients with PTCL-NOS and TFLH. Most recent data are going in the same direction. In a real-life setting, 81 patients with R/R PTCL treated with BV and bendamustine combination,27 the ORR and CR rate were 68% and 49%, respectively, with response lasting >1 year, suggesting that perhaps bendamustine is a better choice for a combination. The romidepsin-CHOP phase 3 study exploratory analysis also suggest the benefit of BV-based therapy in the treatment of PTCL relapses.33 Finally, in the 33 patients of the PTCL cohort (excluding ALCL) of the CheckMate phase 2 study, a combination of BV and nivolumab gave an ORR and CR rate of 45.5% and 33.3%, respectively, with a DOR of 4.6 months.34

In prospective studies evaluating BV-based therapy in PTCL and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, CD30 expression by IHC on tumor samples was an inclusion criterion, with different levels depending upon the studies obtained by local13,15,25,35 or central11,36 assessment. Other than the ALCL entity combining constant and strong CD30 expression and the best BV results, the correlation between CD30 expression and BV efficacy in mature T-cell lymphomas remains unclear.16 Analysis of parameters associated with CD30 was an essential secondary objective of our study. After inclusion, among 63 centrally evaluated patients, 59 (93.6%) had at least 5% CD30+ neoplastic cells by IHC. Applying the ≥10% cutoff of positivity, we did not find any correlation with efficacy, as previously described.16 Conversely, we found a significant negative impact of a high level of baseline sCD30 on both response and survival.

Focusing on patients with TFHL and PTCL-NOS, having less benefit of study treatment, and spanning a wide range of both percentages of CD30+ and of baseline levels of sCD30, an exploratory ad hoc analysis did not find any impact of CD30 expression whereas the level of baseline sCD30 kept a strong predictive impact on outcome. This finding on patients with TFHL and PTCL-NOS has yet to be confirmed by a validation cohort, and the impact of sCD30 should ideally be examined across the main PTCL entities and for other BV-based therapy, including BV monotherapy.

We should note that in our cohort, the correlation between sCD30, response, and survival was not found for ALCL, potentially due to the small sample size. Two other studies also found no correlation between sCD30 and BV efficacy in a series of 25 B-cell and T-cell lymphomas including 10 cases of AITL and 5 cases of EBV-positive PTCL37 and in a series of 32 cases of CTCL.38

While remaining cautious, this sCD30 assay could become a useful predictive marker of BV-based therapy efficacy in the tight timeframe of an aggressive disease and should also be tested in front line and in the context of emerging CD30-targeting therapies including chimeric antigen receptor T cells and bispecific antibodies. CD30 is cleaved by the metalloproteases ADAM10 or ADAM17 form normal and neoplastic cells,39,40 respectively, and its ectodomain sCD30 is released. We speculate that the prognostic impact of high baseline sCD30 could be explained by in vivo neutralization of BV. sCD30 level, which in our study was also associated with advanced stage as well as an intermediate or high International Prognostic Index, could also indicate particular lymphoma aggressiveness as demonstrated in Hodgkin lymphoma.41

The side effects of this study treatment were dominated by hematological AEs. Grade ≥3 neutropenia related to the GBV combination was found in 55%, higher compared with gemcitabine monotherapy (31%)17 and BV monotherapy in ALCL (21%).11 The occurrence of peripheral neuropathy of all grades was also found (21%) but at a level not exceeding that of BV monotherapy in ALCL.11 Of 44 deaths, which occurred during the study, 13 were considered unrelated to lymphoma and 5 during GBV induction including respiratory distress, sudden death, septic shock, sepsis, and or alteration of general condition. In the context of R/R PTCL, the occurrence of this type of complication is not unexpected.

In the difficult task of treating R/R PTCL,2,4 conventional multidrug therapy has produced disappointing results, with no evidence of superiority over limited combinations.9,10 Pralatrexate42 is not registered worldwide. Histone deacetylase inhibitors alone or in combination have an efficacy seemingly linked to the TFH phenotype.43 This includes belinostat44 and romidepsin, the latter withdrawn from the United States market despite positive results.45,46 The oral form of azacytidine in TFHL in the ORACLE phase 3 had an impact on OS but paradoxically no superiority in response.47 Drugs targeting enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2)48 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase49,50 are in development. However, for eligible patients, the best curative approach remains allo-HCT, as we reported in the AATT phase 3 trial long-term analysis.8 It is essential to bridge patients to transplant using an effective and tolerable approach. In this study, of 49 patients deemed eligible based on their age who were aged <70 years and who achieved a response to induction, 9 patients were withdrawn from study with the aim to proceed to HCT.

In conclusion, we show that a widely available combination of GBV followed by BV maintenance, is beneficial in R/R PTCL not only in ALCL but also in the major entity TFHL, and in PTCL-NOS. This study adds to the limited available prospective data advocating the addition of BV in relapse protocols, in all PTCL entities expressing the target of this drug conjugate. In addition, in patients with TFHL and PTCL-NOS we found that blood baseline sCD30 levels could be a useful biomarker of response and survival.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the patients, families, and caregivers who participated in the study. The authors also acknowledge Lymphoma Academic Research Organisation, the operational arm of the LYSA for sponsoring the trial, coordinating the study sites, and conducting the analysis; and all research teams and nurses in the participating centers including the pathologists and the Lymphoma Study Association Pathology for collection and processing of the histopathological material. The authors also thank Takeda Pharmaceuticals for funding the study.

Authorship

Contribution: O.T. and G.L.D. designed and performed research on particular patients’ inclusion and treatment, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; R.D. designed and performed research on particular patients' inclusion and treatment; K.B., M.H., K.L., Sébastien Bailly, M.M., L.Y., S.G., S.L.G., C.B., M.A., J.D., C.T., E.B., N.D., F.M., S.T., C.M., A.B., R.H., A.C., E.G., G.C., H.F., V.C., B.D., H.Z., D.S., E.N.-V., C.D., Sarah Bailly, and S.C. performed research on particular patients' inclusion and treatment; S.L., T.B., and M.-H.D.-L. performed research, in particular, soluble serum CD30 analysis; P.G., A.L.-P., M.P., and L.d.L. performed research in pathology review and CD30 expression assessments; and S.G. performed statistical analysis.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: O.T. received travel grants and honoraria from Takeda, AbbVie, BeiGene/BeOne, and AstraZeneca; research support from Takeda; and honoraria from Ideogen. M.A. served on advisory boards for Takeda, Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead, Incyte, Sobi, and BeiGene; received institutional research grants from Roche, Johnson & Johnson, and Takeda; and travel grants from Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Gilead, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, and Takeda. J.D. received travel grants from Janssen and BeiGene/BeOne; and honoraria from BeiGene/BeOne and AstraZeneca. S.T. received travel grants from Takeda and BeiGene/BeOne. G.C. served as a consultant for Takeda, Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Roche, Ownards Therapeutics, MAbQI, and AbbVie; received honoraria from Takeda, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead, Roche, Janssen, and AbbVie; and travel grants from Novartis, Gilead, Roche, and Janssen. V.C. received honoraria from Incyte, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Ideogen, Janssen, Kiowa Kirin, Kite/Gilead, Lilly, Novartis, Octapharma, Secura Bio, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Takeda. D.S. received travel grants and honoraria from Takeda. R.D. is an employee and stock owner of BeiGene/BeOne. P.G. received travel grants, honoraria, and research support from Takeda. L.d.L. served as a consultant for Roche; on advisory boards for AbbVie and Novartis; as a speaker for Takeda, all institutional; and received travel support from Roche. G.D. received travel support from Takeda and Amgen; and research support from Takeda and Ideogen. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Olivier Tournilhac, Hematology and Cell Therapy, Clermont-Ferrand University Hospital, UCA, EA7453 Chelter Centre d'Investigation Clinique-1405, 1 Pl Lucie et Raymond Aubrac, 63003 Clermont-Ferrand Cedex 1, France; email: otournilhac@chu-clermontferrand.fr.

References

Author notes

K.B. and S.L. contributed equally to this study.

Publication-related data will be shared upon reasonable project outline on request from the corresponding author, Olivier Tournilhac (otournilhac@chu-clermontferrand.fr).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.