Key Points

Abatacept reduced incidence of endothelial injury syndromes and improved survival in patients with TDT.

Patients receiving abatacept did not experience grade 2 to 4 acute GVHD.

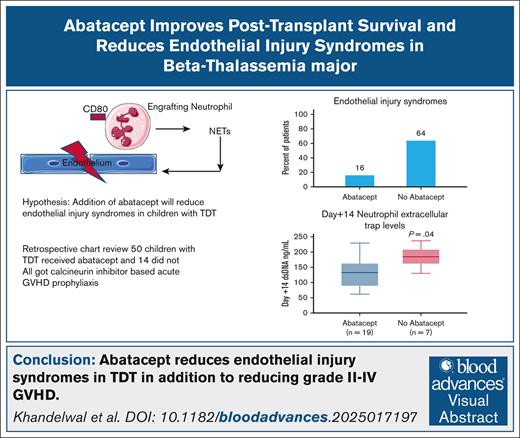

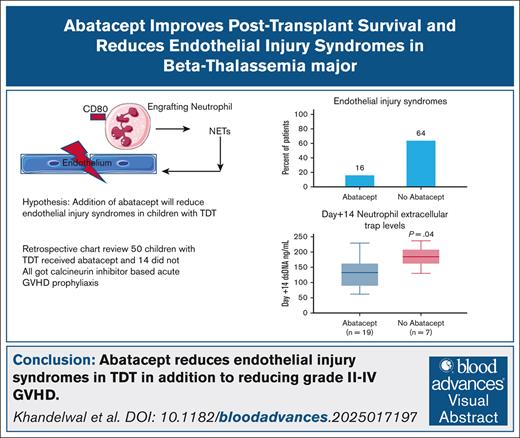

Visual Abstract

Iron overload in transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia (TDT) generates reactive oxygen species, predisposing to post–hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) endothelial activation. Abatacept prevents acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) by inhibiting CD80/CD86 on T cells, but CD80 is also expressed on neutrophils. Elevated neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) at day +14 are associated with thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) after HSCT, mechanistically linking endothelial activation to complement activation. We wanted to compare post-HSCT survival and incidence of endothelial injury syndromes in children with TDT with and without addition of abatacept to standard GVHD prophylaxis. We performed a retrospective review of children with TDT who underwent HSCT at our center. Patients without abatacept served as controls. A total of 64 children underwent HSCT for TDT. Fifty received abatacept and 14 did not. Acute grade 2 to 4 GVHD was lower in the abatacept cohort (0%) compared with the no-abatacept cohort (35%). Incidence of any endothelial injury syndromes (transplant-associated TMA, sinusoidal obstructive syndrome, posterior reversible encephalopathy, and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage) was lower in the abatacept cohort (16%) compared with no abatacept (64%; P = .0009). Day +14 double-stranded DNA (surrogate of NETs) and soluble c5b-9 were lower in the abatacept cohort than the no-abatacept cohort (P = .04 and P < .001, respectively). All patients in the abatacept cohort had full donor myeloid chimerism and remained transfusion independent at a median last follow-up of 1915 days (range, 266-3464) after HSCT. Thalassemia-free survival was 100% in the abatacept cohort and 71% in the no-abatacept cohort. Addition of abatacept to calcineurin inhibitor–based GVHD prophylaxis resulted in excellent thalassemia-free survival and lower endothelial injury syndromes.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a curative therapy for transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia (TDT), a genetic disorder characterized by ineffective erythropoiesis and severe anemia necessitating lifelong blood transfusions.1 Advances in transplantation have significantly improved outcomes, especially in children.2-4 Large cohort studies have reported overall survival rates of >85% in children undergoing matched sibling donor HSCT, with event-free survival rates of 75% to 80% in many centers.5-8 Myeloablative conditioning regimens incorporating busulfan, fludarabine, and thiotepa have demonstrated efficacy in overcoming graft rejection in high-risk patients with significant iron overload or previous alloimmunization.8,9

Patients with β-thalassemia are at heightened risk for transplant-related complications due, in part, to chronic iron overload from repeated transfusions.10 Excess iron accumulates in various organs and catalyzes the formation of reactive oxygen species, resulting in oxidative stress and tissue damage.10 This prooxidative milieu can injure the vascular endothelium, predisposing to endothelial dysfunction11 and promoting a proinflammatory state11 that may exacerbate graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) pathogenesis and other endothelial injury–related complications such as sinusoidal obstruction syndrome.12 Endothelial activation also fosters leukocyte recruitment and neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation, further amplifying inflammatory cascades.13 Strategies that mitigate oxidative and endothelial stress in patients with TDT undergoing HSCT could reduce transplant toxicity and improve outcomes.

Abatacept is a fusion protein composed of the extracellular domain of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 linked to a modified Fc portion of human immunoglobulin G1.14 It selectively modulates T-cell activation by binding to CD80 and CD86, thereby inhibiting CD28-mediated costimulation.14 Originally approved for autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis,15 abatacept is now approved for preventing acute GVHD in the setting of unrelated donor HSCT.16,17 Beyond its immunomodulatory effects, abatacept has also been implicated in reducing the formation of NETs, which are released by activated neutrophils during inflammatory responses.18

Limited data exist on reduction of endothelial injury syndromes after HSCT in children with TDT. Several acute GVHD prophylactic agents including calcineurin inhibitors, sirolimus, and posttransplant cyclophosphamide have been associated with increased risk of endothelial and complement activation after HSCT.19-22 Although posttransplant cyclophosphamide has significantly reduced severe acute and chronic GVHD in limited case series of children with TDT,23 emerging literature shows perturbation of the endothelium by posttransplant cyclophosphamide, lending interest to approaches that reduce GVHD and simultaneously reduce incidences of endothelial activation.22

We have previously shown reduction of severe acute GVHD with addition of 4 doses of abatacept to standard calcineurin inhibitor–based acute GVHD prophylaxis in children with TDT.24 We hypothesized that the addition of abatacept to standard GVHD prophylaxis would reduce the incidence of endothelial injury syndromes and improve survival outcomes in children with TDT undergoing HSCT. In this report, we show a reduction in all endothelial activation–related events along with improvement in thalassemia-free survival in TDT with addition of 4 doses of abatacept, and hypothesize that abatacept may reduce endothelial activation by reducing NETosis as a novel and underrecognized mechanism of action.

Methods

This retrospective study received approval from the institutional review board at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center and includes all patients who underwent allogeneic HSCT for TDT at our center between January 2010 and March 2024. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing was performed for 10 alleles (HLA-A, B, C, DR, and DQ) using molecular techniques. Details of donor relation and stem cell source were collected.

All participants received a conditioning regimen that included IV busulfan for 4 consecutive days, with doses adjusted to achieve a pharmacokinetic target area under the curve of 3900 to 4200 μmol∗min/d or 62 to 68 mg∗h/L. This was followed by 4 days of IV fludarabine (40 mg/m2 per day) and 2 days of thiotepa (5 mg/kg per day). An initial busulfan test dose (0.8-1.0 mg/kg) was administered within a week before conditioning to guide dosing. None of the patients received preconditioning with hydroxyurea or azathioprine, as per our institutional practice. Red blood cell transfusions continued per routine before transplantation without intensification.

Patients were divided into 2 groups for comparison, those who received abatacept and those who did not. All patients without abatacept served as controls. The no-abatacept group received a calcineurin inhibitor and corticosteroids (1 mg/kg per day from day +1 to day +28) with or without maraviroc from day −3 to day +30 after HSCT.25 The abatacept group received additional calcineurin inhibitors and either corticosteroids or mycophenolate mofetil. Abatacept was administered IV at 10 mg/kg (maximum dose of 1000 mg) on days −1 before transplant, and +5, +14, and +28 after transplant.16

Our center’s practice is to perform liver biopsies if liver iron content (LIC) estimated by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) T2∗ is >10 000 μg of iron per g dry weight of liver. Mild, moderate, and severe iron overload was defined as a LIC of 3500 to 7000 μg/g dry weight of liver, 7000 to 12 000 μg/g dry weight of liver, and >12 000 μg/g dry weight of liver, respectively.

Patients were classified as high risk if they were aged >7 years and had a palpable liver >2 cm below the costal margin, whereas presence of either age of >7 years without hepatomegaly or hepatomegaly in a child aged <7 years classified them into moderate risk. Age of <7 years and no hepatomegaly classified patients into low risk.5

Diagnosis and grading of acute and chronic GVHD were performed by the treating physicians, using the modified Glucksberg26 and 2005 National Institutes of Health consensus criteria,27 respectively. Patient records were reviewed for data on pretransplant iron burden (liver and cardiac, via T2∗ MRI), neutrophil and platelet engraftment timing, donor myeloid chimerism, incidence and severity of acute and chronic GVHD and endothelial injury syndromes such as sinusoidal obstructive syndrome (SOS), transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy (TA-TMA), posterior reversible encephalopathy (PRES) and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH),28 transfusion requirements, and infections through the last follow-up. Clinical soluble C5b-9 (sC5b-9) values tested before transplant and at day +7 and day +14 after HSCT were also collected for patients if these were available to compare pretransplant (baseline), day +7, and day +14 complement activation status.

All HSCT recipients at our center were prospectively screened for TA-TMA starting at pretransplant baseline until at least day +100, or TA-TMA resolution if later, and prospectively diagnosed and risk stratified for TA-TMA using Jodele criteria, as we have previously published.29-31All patients with TA-TMA stratified as high risk received targeted therapy with complement blocking agent eculizumab as first line of therapy.32 SOS was diagnosed using the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation criteria for children.33

Circulating double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) was used as a surrogate for NETs34,35 and was quantified on day +14 using the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA reagent and kit in a subset of children (n = 26) for whom samples were available from our institutional biorepository.

Outcomes were compared between those receiving no abatacept and those who received abatacept. For endothelial injury syndromes, we compared the incidence of any endothelial injury syndrome including TA-TMA, SOS, PRES, or DAH between the 2 cohorts and compared each syndrome separately between both cohorts. Continuous variables were reported as medians with interquartile ranges, whereas categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Fisher exact test were used to assess differences across groups. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated, and the log-rank test was applied for group comparisons. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to assess additional factors beyond abatacept contributing to endothelial injury–related events, using age at HSCT and HLA match as additional variables. All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 3.2.4; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), with a significance threshold of P value <.05

Results

Demographics

A total of 64 children underwent allogeneic HSCT for TDT. Demographics are shown in Table 1. Fifty children received abatacept in addition to standard calcineurin inhibitor–based prophylaxis and 14 children received standard calcineurin inhibitor–based acute GVHD prophylaxis without abatacept. Six children in the no-abatacept cohort received maraviroc from day −3 to day +30.25 Median age in the abatacept cohort was 6.5 years (range, 2-13) whereas median age in the no-abatacept cohort was 7.3 years (range, 2-18.8; P = .5). All children in both cohorts received busulfan, fludarabine, and thiotepa as their preparative regimen. Busulfan dosing was based on pharmacokinetic studies. Both cohorts had comparable demographics including similar 10 of 10 HLA matches (80% in the abatacept cohort vs 78% in no-abatacept cohort; P = .9), unrelated donors (38% in abatacept cohort vs 35% in no-abatacept cohort; P = .9), and bone marrow as stem cell source (80% in abatacept cohort vs 85% in the no-abatacept cohort; P = .9). All patients received antimicrobial prophylaxis against fungi, Pneumocystis jerovecii as per institutional practice. All patients were on acyclovir prophylaxis as per standard institutional practice. No patient experienced infusion-related adverse effects to abatacept.

Risk stratification

Risk stratification was based on age at HSCT (age of <7 or >7 years) and hepatomegaly, as previously published.5 Most children were deemed to be low risk at the time of HSCT in both cohorts (64% in abatacept cohort vs 64% in the no-abatacept cohort). No patient underwent liver biopsy because the median pre-HSCT LIC as estimated by MRI T2∗ was 4395 μg/g (range, 1666-9742) in the abatacept cohort and 4471 μg/g (range, 1658-6800) in the no-abatacept cohort (P = .7). No patient in either group had evidence of myocardial iron deposition before HSCT.

Engraftment

Neutrophil engraftment, defined as an absolute neutrophil count of 0.5 × 103/μL for 3 consecutive days, was achieved at a median of 12 days (range, 9-14) in the abatacept cohort and 11 days (range, 9-15) in the no-abatacept cohort (P = .1). Platelet engraftment, defined as a platelet count of 20 000/μL at least 7 days from the last platelet transfusion, was achieved at a median of 18 days (range, 13-43) in the abatacept cohort and a median of 16 days (range, 12-81) in 13 children in the no-abatacept cohort (P = .4). The lowest documented myeloid chimerism at any time until last follow-up in both cohorts was 100%. All patients in the abatacept cohort had full donor myeloid chimerism at a median last follow-up of 1915 days (range, 266-3593) after HSCT. All patients in the no-abatacept cohort had full donor myeloid chimerism at a median time of death or last follow-up of 3622 days (range, 65-5498; Table 2).

GVHD

Confirming our previously published observations,24,36 acute grade 2 to 4 GVHD was 0% in the abatacept cohort compared with 35% in the no-abatacept cohort (P = .0003). Incidence of grade 1 to 4 acute GVHD was 14% (all grade 1) in the abatacept cohort compared with 64% in the no-abatacept cohort (grade 1, n = 4; grade 3-4, n = 5; P = .0004). In the no-abatacept cohort, acute GVHD was observed in fully matched family donors (n = 6), fully matched unrelated donor transplants (n = 2), and single antigen mismatched unrelated donor transplant (n = 1). Importantly , in the no-abatacept cohort, grade 3 to 4 GVHD was observed in 5 patients, of whom 3 received matched related donor transplants, 1 received a matched unrelated donor transplant, and 1 received a mismatched unrelated donor transplant. The incidence of visceral acute GVHD was 0% in abatacept cohort compared with 35% in no-abatacept cohort (P = .0003). The incidence of 1-year chronic GVHD was 14% in the abatacept cohort and 35% in the no-abatacept cohort (P = .1). The incidence of moderate-severe chronic GVHD was 10% in the abatacept cohort and 28% in the no-abatacept cohort (P = .09; Table 2)

Endothelial injury syndromes

Endothelial injury syndromes were compared between both cohorts, including TA-TMA, SOS, PRES, and DAH.28 We first compared the incidence of any endothelial injury syndrome between both cohorts and then compared individual complications separately. Median day after HSCT of onset of any endothelial injury syndrome was 23 days after HSCT (range, 8-91) in the abatacept cohort and 36 days (range, 16-157) in the no-abatacept cohort. The median day after HSCT of onset of TA-TMA was 38 days (range, 17-91) in the abatacept cohort and 36 days (range, 16-157) in the no-abatacept cohort. SOS was diagnosed on day +8 and +50 after HSCT in the abatacept cohort and day +56 and day +73 after HSCT in 2 patients in the no-abatacept cohort. PRES was diagnosed at day +19 after HSCT in 1 patient in the abatacept cohort and day +35 in 1 patient in the no-abatacept cohort.

There was a significant reduction in endothelial injury–related complications in patients who received abatacept. Incidence of any endothelial injury syndromes (TA-TMA, SOS, DAH, or PRES) was 16% in the abatacept cohort compared with 64% in children who did not receive abatacept (P = .0009). Incidence of moderate-severe TMA was 6% in the abatacept cohort compared with 57% in the no-abatacept cohort (P < .001). Incidence of all-risk TMA was 12% in the abatacept cohort compared with 64% in the no-abatacept cohort (P = .002; Table 2). The incidence of high-risk TMA was 4% in the abatacept cohort and 21% in the no-abatacept cohort (P = .06). Incidence of SOS was 4% in the abatacept cohort and 14% in the no-abatacept cohort (P = .2); and incidence of PRES was 2% in the abatacept cohort and 7% in the no-abatacept cohort(P = .3). No patient in either cohort experienced DAH. Three patients (21%) in the no-abatacept cohort had >1 endothelial injury syndrome (TMA and SOS, n = 2; TMA and PRES, n = 1) compared with 1 patient (2%) in the abatacept cohort (TMA and SOS; P = .03; Table 1).

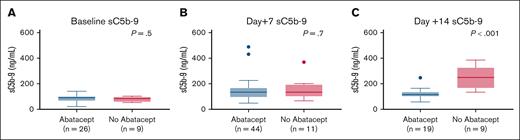

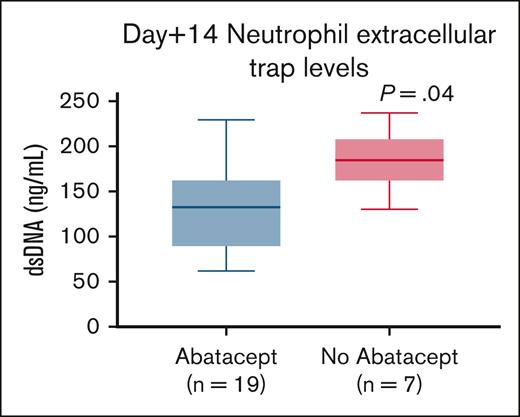

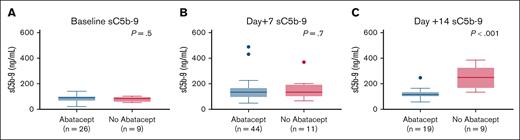

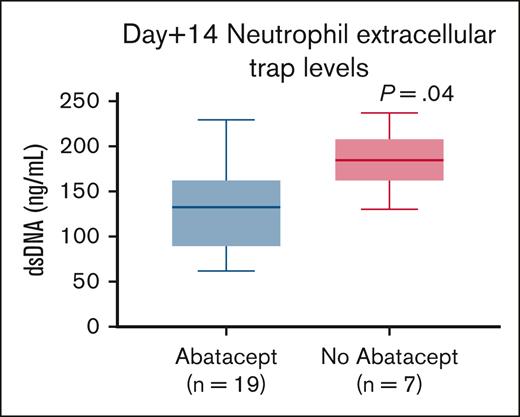

Median pre-HSCT sC5b-9 values were 87.5 ng/mL (range, 33-140) in 26 children who received abatacept and 83 ng/mL (range, 53-102) in 9 children who did not receive abatacept (P = .5), indicating similar complement activation status before proceeding to transplant in both groups (Figure 1A). Median sC5b-9 values at day +7 were 134.5 ng/mL (range, 48-489) in 44 children who received abatacept compared with 134 ng/mL (range, 66-369) in 11 children who did not receive abatacept(P = .7; Figure 1B. Day +14 median sC5b-9 values were 115 ng/mL(range, 58-247) in 19 children who received abatacept compared with 249 ng/mL (range, 134-385) in 9 children who did not receive abatacept (P < .001; Figure 1C). To further investigate the role of NETs in reduction of endothelial injury–related events, we quantified NETs in both cohorts using dsDNA as a surrogate in a subset of patients for whom we had available cryopreserved biospecimens in our transplant tissue repository. Median plasma dsDNA at day +14 after HSCT was 131.9 ng/mL (range, 62-229) in children who received abatacept (n = 19) compared with 184.5 ng/mL (range, 130-236) in children who did not receive abatacept (n = 7; P = .04; Figure 2).

sC5b-9 levels are lower in abatacept cohort at day +14 post-HSCT. (A) Pretransplant sC5b-9 values are similar between abatacept and no-abatacept cohorts, indicating similar complement activation status before proceeding with HSCT. (B) Day +7 post-HSCT sC5b-9 values are similar between abatacept and no-abatacept cohort. (C) Day +14 post-HSCT sC5b-9 values are higher in the no-abatacept cohort than in the abatacept cohort, suggesting lower complement activation in the abatacept cohort.

sC5b-9 levels are lower in abatacept cohort at day +14 post-HSCT. (A) Pretransplant sC5b-9 values are similar between abatacept and no-abatacept cohorts, indicating similar complement activation status before proceeding with HSCT. (B) Day +7 post-HSCT sC5b-9 values are similar between abatacept and no-abatacept cohort. (C) Day +14 post-HSCT sC5b-9 values are higher in the no-abatacept cohort than in the abatacept cohort, suggesting lower complement activation in the abatacept cohort.

Neutrophil extracellular traps are lower in the abatacept cohort. Day +14 post-HSCT dsDNA levels in the abatacept cohort are lower than those of patients who did not receive abatacept for TDT.

Neutrophil extracellular traps are lower in the abatacept cohort. Day +14 post-HSCT dsDNA levels in the abatacept cohort are lower than those of patients who did not receive abatacept for TDT.

We performed univariate and multivariate analyses to see whether HLA mismatch or age at HSCT also influenced endothelial injury–related events (supplemental Table 1). The use of abatacept remained statistically significantly associated with reduced endothelial injury–related events on multivariate analyses, odds ratio of 0.09 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.02-0.36; P = .001).

Infectious complications

Bloodstream infections (BSI) were observed in both cohorts. Seven children (14%) had bacteremia in the abatacept cohort compared with 5 children (35%) in the no-abatacept cohort (P = .1). Details of organisms involved including the day after HSCT when bacteremia occurred are shown in Table 3. Median days of BSI was 38 days after HSCT (range, day −8 to day +176) in the no-abatacept cohort and 7 days (range, 3-61) after HSCT in the abatacept cohort. All BSI in both cohorts were successfully treated with antibiotics.

Asymptomatic viremias were also observed in both cohorts (Table 3). The incidence of any asymptomatic viral reactivation was 80% in the abatacept cohort and 71% in the no-abatacept cohort (P = .4). Incidence of viral disease was 21% in the no-abatacept cohort and 14% in the abatacept cohort (P = .6; Table 3). Asymptomatic cytomegalovirus (CMV) viremia and CMV pneumonitis in both cohorts were successfully treated with antivirals including foscarnet and ganciclovir and virus-specific T-cell infusions. Asymptomatic Epstein-Barr virus viremia was treated with rituximab and virus-specific T-cell infusions. BK virus hemorrhagic cystitis in both cohorts was managed with virus-specific T cells; and disseminated adenoviremia in 1 patient in the no-abatacept cohort was treated with IV cidofovir.

Immune reconstitution and survival

The median last follow-up for the abatacept cohort is 1915 days (range, 266-3593) after HSCT, whereas the median follow-up for surviving patients of the no-abatacept cohort is 3785 days (range, 3243-5498) after HSCT.

Median absolute CD4+ counts at 6 months were 376 cells per μL (range, 5-1690) in the no-abatacept cohort and 441 cells per μL (range, 71-802) in the abatacept cohort. All surviving patients in both cohorts are transfusion independent at last follow-up.

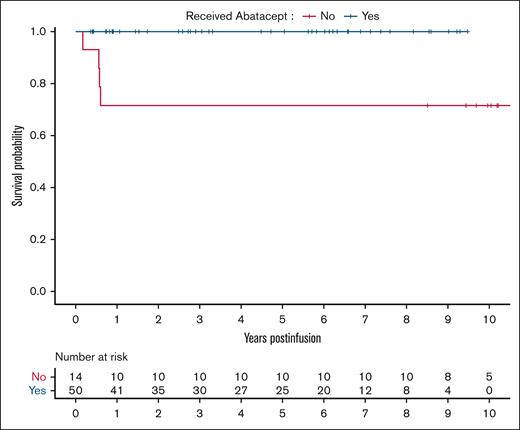

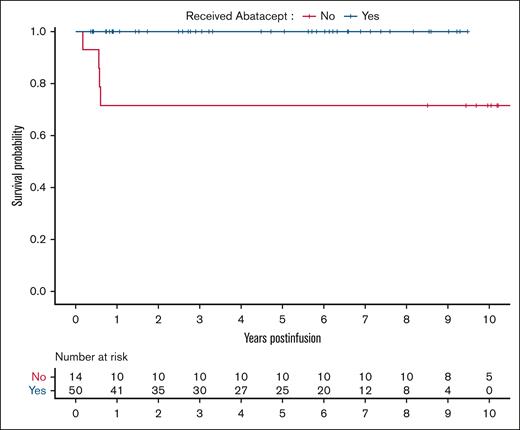

Thalassemia-free survival was 100% in the abatacept cohort and 71% in the no-abatacept cohort (Figure 3). Four children in the no-abatacept cohort died at a median of 208 days (range, 65-220) after HSCT due to multiorgan failure from SOS (n = 1), disseminated adenoviremia leading to multiorgan failure (n = 1), disseminated Aspergillus infection (n = 1), and CMV pneumonitis (n = 1), all in the setting of GVHD. Notably all 4 patients had active TA-TMA at time of death.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of children with TDT who received abatacept (n = 50) and those who did not receive abatacept (n = 14).

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of children with TDT who received abatacept (n = 50) and those who did not receive abatacept (n = 14).

Discussion

We show an impressive thalassemia-free survival and reduction in endothelial injury syndrome incidences with the addition of 4 doses of abatacept to standard calcineurin inhibitor–based acute GVHD prophylaxis in a busulfan-based conditioning regimen. In this TDT cohort, we not only confirm striking reduction in incidence of grade 2 to 4 acute GVHD with this approach but also show significant reduction in endothelial injury syndromes including moderate-high-risk TA-TMA, SOS, DAH, and PRES. We included both matched and mismatched donors and unrelated and matched family donors in our study and demonstrated benefit compared with a historical cohort of patients who received transplantation at our center without abatacept. Our incidence of moderate-severe TMA was unusually high in the control group predominantly comprised of matched donor transplants, without known reasons for such predisposition or occurrence. Abatacept was well tolerated and was not associated with infusion-related side effects.

Although morbidity and mortality associated with acute GVHD is well defined, we are now becoming increasingly aware of endothelial injury syndromes affecting posttransplant outcomes.29,37 Our group and others have reported in prospective studies and retrospective observations, that endothelial injury syndromes such as TA-TMA, SOS, DAH, and PRES adversely affect posttransplant outcomes and are associated with higher risk of developing multiorgan injury syndromes with limited targeted therapeutic strategies available.32,38,39 Patients with endothelial injury syndromes often require intensive care unit care and have prolonged hospital stay.29,39 These patients remain at high risk for long-term organ injury and increased need for chronic care in addition to adverse short-term impacts on health and financial burden.32,40 Reducing the incidence of endothelial injury syndromes by upfront preventive strategies, such as incorporating abatacept in transplant for TDT, has multiple favorable outcomes, from preserving health to reducing financial burden.

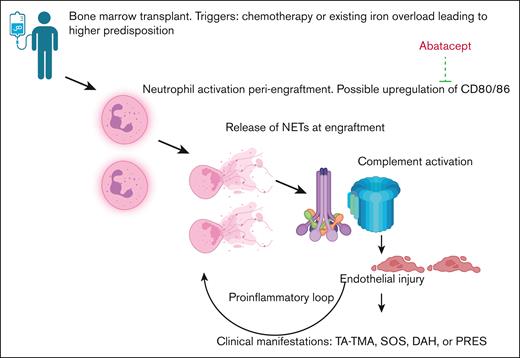

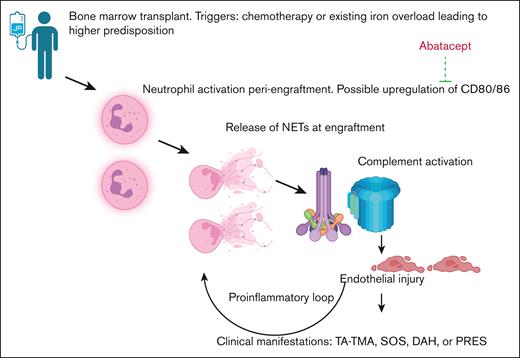

It is generally assumed that lower incidence of acute GVHD could lead to lower incidence of TMA, but we show lower day +14 dsDNA and sC5b-9 levels in the abatacept cohort compared with a no-abatacept cohort, which offer a possible explanation of the lower rates of endothelial injury, independent of acute GVHD incidence. NETs have been shown to activate complement41,42 and an early spike in dsDNA production around day +14 during engraftment was associated with subsequent TA-TMA development in ∼100 pediatric consecutive allogeneic HSCT recipient.43 Because CD80/CD86 is also expressed on activated neutrophils,44 abatacept could also lower complement activation by reducing peak dsDNA levels and reducing NETosis, suggesting a novel and previously underrecognized mechanism of action. Our proposed hypothesis is shown in Figure 4. Baseline sC5b-9 levels, available for a subset of patients in both cohorts, showed similar complement activation before transplant, indicating no inherent differences between the groups. By day +7 after HSCT, the abatacept cohort had received 2 doses of abatacept on days −1 and +5. However, because no patients achieved neutrophil engraftment by day +7, presumably NETosis had not yet begun (Figure 4). Therefore sC5b-9 levels remained similar between the abatacept and no-abatacept cohorts at day +7, suggesting similar levels of complement activation between both cohorts. However, by day +14 after HSCT, both dsDNA and sC5b-9 levels were lower in the abatacept group. These limited data, although not directly demonstrative of mechanism, could suggest that lower NETosis was associated with lower levels of complement activation, resulting in lower incidence of endothelial injury syndromes.

Schematic hypothesis of how abatacept reduces endothelial injury post-HSCT. Hypothesis of our proposed mechanism including neutrophil activation leading to production of NETs, activation of complement system, and endothelial injury, along with the possible role of abatacept in ameliorating these manifestations.

Schematic hypothesis of how abatacept reduces endothelial injury post-HSCT. Hypothesis of our proposed mechanism including neutrophil activation leading to production of NETs, activation of complement system, and endothelial injury, along with the possible role of abatacept in ameliorating these manifestations.

Ibrahimova et al have also shown reduction of NETs and lower sC5b-9 level in patients receiving abatacept compared with standard calcineurin inhibitor use in a large cohort of pediatric and young adult patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT.18 Moreover, a recent publication has demonstrated a unique vascular toxicity with the use of posttransplant cyclophosphamide, possibly contributing to endothelial injury.45 Posttransplant cyclophosphamide reduces acute GVHD significantly, but this reduction does not translate to reducing endothelial activation, suggesting that reduction of acute GVHD does not always eliminate endothelial injury syndromes.

The addition of abatacept did not adversely affect myeloid chimerism or lead to graft failure, which is different to treosuflan-based conditioning regimens for TDT, in which the incidence of graft rejection is reported to be 5% to 11% and incidence of mixed chimerism is reported to be 25% to 30%.46,47 In a separate randomized study of either busulfan or treosulfan with fludarabine and thiotepa for nonmalignant indications, there were more graft failures in the treosulfan arm (21%) compared with busulfan arm (4%).48 Lüftinger et al performed a retrospective European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation analysis of 772 patients, 410 of whom received busulfan/fludarabine- and 362 treosulfan/fludarabine-based conditioning.49 Two-year overall survival was 92.7% (95% CI, 89.3-95.1) after busulfan and 94.7% (95% CI, 91.7-96.6) after treosulfan.49 The incidence of second HSCT at 2 years was 4.6% in the busulfan vs 9.0% in the treosulfan group.49 We show reduction in toxicities with abatacept leading to improvement in survival, while maintaining curative levels of myeloid chimerism with our busulfan-based preparative regimen, which could be an alternative safe approach to treat TDT.

Four doses of abatacept at day −1, +5, +14, and +28 did not reduce the incidence of moderate-severe chronic GVHD, consistent with previous published reports.17,24 Results from the extended dosing of abatacept trial will shed light on whether extending the course of treatment may reduce the incidence of chronic GVHD. In the abatacept cohort, the incidence of moderate-severe chronic GVHD was low at 10%, consistent with low overall rates of this complication in children.50

Posttransplant cyclophosphamide leads to significant reduction in incidences of severe acute GVHD and chronic GVHD.51 Limited published reports exist on use of posttransplant cyclophosphamide for TDT, but a preliminary report of 40 children with TDT demonstrated a 7.5% incidence of acute GVHD and 10% incidence of chronic GVHD.52 No data were included on endothelial activation syndromes in the aforementioned study.52 We demonstrate significant reduction in incidences of severe acute GVHD and endothelial activation syndromes with the use of 4 doses of abatacept with excellent thalassemia-free survival. These attributes of abatacept have to be balanced by the lack of reduction of the incidence of chronic GVHD, which are observed with posttransplant cyclophosphamide, but studies are underway to determine whether extended dosing abatacept may reduce chronic GVHD.

Infectious complications were similar between both cohorts, but viral reactivation remains the largest challenge with abatacept, especially because these occurred without concurrent GVHD or escalating immune suppression, as was seen in the no-abatacept cohort. We advocate access to virus-specific T-cell infusions to manage viremias in addition to antiviral prophylaxis with letermovir in addition to acyclovir for eligible patients to reduce the risk of viral reactivation.

Gene therapy has emerged as a transformative treatment for TDT, with the US Food and Drug Administration approving betibeglogene autotemcel for patients aged ≥4 years53 and exgamaglogene autotemcel for patients aged ≥12 years.54 Despite these promising outcomes, the high cost of therapy and complex administration requirements limit their accessibility, particularly in low- and middle-income countries in which TDT prevalence is highest.55 Consequently, HSCT remains the primary curative option in these regions and ongoing efforts to enhance transplant protocols are essential to improve clinical outcomes.

Our study is limited by its small sample size and its retrospective study design. We were unable to assess CD80/CD86 expression on neutrophils at day +14 due to challenges with performing flow cytometry on cryopreserved neutrophils. We are unable to show baseline values of NETs between the 2 cohorts because we do not have cryopreserved samples at baseline in the no-abatacept cohort but show clinical sC5b-9 values at baseline, day +7, and day +14 after HSCT. Furthermore, there is a sample size imbalance between the 2 cohorts that could introduce bias and limit statistical power. Although we included all consecutive patients with TDT who underwent HSCT at our center, the retrospective, nonrandomized study design could raise the possibility of selection bias. The lack of baseline dsDNA values in both groups limits the strength of our observations in the mechanistic role of abatacept in reducing NETs. Finally, we included patients who received maraviroc and corticosteroids in the control group for acute GVHD prophylaxis, contributing to heterogeneity in our comparison groups. Despite our limitations, we show a significant reduction in mortality and complications with the addition of 4 doses of abatacept to calcineurin inhibitor–based acute GVHD prophylaxis, when using busulfan-based conditioning regimen, regardless of HLA match or donor relation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank clinical staff, patients, and families. The authors also thank the Bone and Marrow Transplant repository and the S.M.D. laboratory for assistance with procuring cryopreserved biospecimens.

Authorship

Contribution: P.K. collected data and wrote the manuscript; A.L. performed statistical analyses; A.I. performed double-stranded DNA experiments; S.M.D. and M.G. critically read the manuscript and provided feedback; S.J. oversaw the study and provided critical feedback; and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Pooja Khandelwal, Division of Bone Marrow Transplantation and Immune Deficiency, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Ave, Cincinnati, OH 45229; email: pooja.khandelwal@cchmc.org.

References

Author notes

Deidentified data are available on request from the corresponding author, Pooja Khandelwal (pooja.khandelwal@cchmc.org).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.