Key Points

Monoclonal and polyclonal anti-PRT/heparin antibodies are serologically distinct from anti-PF4/heparin antibodies.

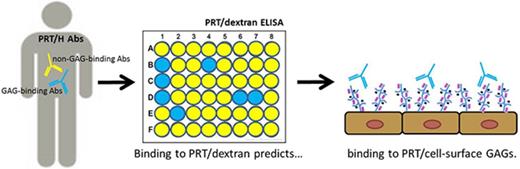

Binding of anti-PRT/heparin antibodies to PRT/dextran complexes correlates with PRT/GAG reactivity.

Abstract

Anti-protamine (PRT)/heparin antibodies are a newly described class of heparin-dependent antibodies occurring in patients exposed to PRT and heparin during cardiac surgery. To understand the biologic significance of anti-PRT/heparin antibodies, we developed a murine monoclonal antibody (ADA) specific for PRT/heparin complexes and compared it to patient-derived anti-PRT/heparin antibodies, as well as comparing polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies with anti–platelet factor 4 (PF4)/heparin. Using monoclonal antibodies and polyclonal patient-derived antibodies, we show distinctive binding patterns of anti-PRT/heparin antibodies as compared with PF4/heparin antibodies. Whereas heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) antibody binding to PF4/heparin is inhibited by relatively low doses of heparin (0-1 U/mL), anti-PRT/heparin antibodies, including ADA, retain binding to PRT/heparin over a broad range of heparin concentrations (0-50 U/mL). Unlike PF4/heparin antibodies, which recognize PF4 complexed to purified or cell-associated glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), anti-PRT/heparin antibodies show variable binding to cell-associated GAGs. Further, binding of anti-PRT/heparin antibodies to PRT/dextran complexes correlates closely with the ability of antibodies to bind to cell-surface PRT. These findings suggest that antibody binding to PRT/dextran may identify a subset of clinically relevant anti-PRT/heparin antibodies that can bind to cell-surface GAGs. Together, these findings show important serologic differences between HIT and anti-PRT/heparin antibodies, which may account for the variability in disease expression of the two classes of heparin-dependent antibodies.

Introduction

Recent studies suggest that ∼25% of patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) develop antibodies to protamine (PRT)/heparin complexes.1-3 Although anti-PRT/heparin antibodies share a number of serologic properties with anti–platelet factor 4 (PF4)/heparin antibodies, including enhanced binding in the presence of heparin, platelet activation, and serologic transience, the clinical significance of these antibodies remains uncertain. In our prior study, although anti-PRT/heparin antibodies at the time of cardiac surgery were associated with a trend toward long-term adverse outcomes and major adverse cardiovascular events, no short-term complications were seen in seropositive patients.2 Similarly, a recent study of 24 patients with preformed anti-PRT/heparin antibodies who were re-exposed to drug during CPB found no association of anti-PRT/heparin antibodies with perioperative outcomes, including thrombocytopenia, hemorrhage, or thromboembolic events.4 In contrast, other studies have noted serious clinical complications in seropositive patients, including severe thrombocytopenia5 and arterial thrombosis in association with platelet-activating antibodies.3,6

The disease heterogeneity associated with anti-PRT/heparin antibodies suggests that these antibodies may exhibit biologic heterogeneity as well. To understand such differences, we examined binding specificities of anti-PRT/heparin antibodies and compared them with anti-PF4/heparin antibodies, a well-recognized class of heparin-dependent antibodies that are causative of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). To facilitate these investigations, we developed a heparin-dependent murine monoclonal antibody to PRT/heparin complexes (ADA). Our studies suggest that ADA, some polyclonal anti-PRT/heparin antibodies, and anti-PF4/heparin antibodies show differential reactivity to PRT/heparin or PF4/glycosaminoglycan (GAG) complexes. Our studies suggest that these biologic differences may define antibody subpopulations with the potential to cause disease in the absence of heparin.

Methods

Patient samples

With institutional review board (IRB) approval (Duke University Medical Center IRB #Pro00010736), patient-derived anti-PRT/heparin antibodies were obtained from cardiac surgery patients enrolled at Duke in the HIT 5801 study, a prospective multicenter study of patients with HIT undergoing cardiac surgery. Additional samples from patients with HIT were obtained after informed consent (IRB #Pro00012901). Stored plasma samples with high antibody reactivity to PRT/heparin (A450 nm > 2.5) or to PF4/heparin complexes (A450 nm > 2.0) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) were used as a source of respective patient-derived polyclonal anti-PRT/heparin or anti-PF4/heparin antibodies. Because of limited availability of patient samples containing anti-PRT/heparin antibodies, platelet-activation assays could not be performed.

Monoclonal antibodies to PRT/heparin and PF4/heparin

ADA, a monoclonal immunoglobulin (Ig) of IgG3κ subclass, was developed after immunization of 6- to 8-week-old female BALB/c mice with PRT/heparin complexes using previously described protocols7 and institutional approval (Departmental Animal Care University Committee protocol #A205-13-08). Titers of anti-PRT/heparin were monitored by ELISA. Fusion was performed using the immortalized myeloma cell line P3X63Ag8U.1,p.Unk (CRL-1597; ATCC, Manassas, VA) and splenocytes from mice expressing the highest serum titers. A hybridoma clone showing reactivity to PRT/heparin much greater than PRT was identified among 152 screened hybridomas and further subcloned by limiting dilution. Hybridomas were grown in BD Cell Line CL-1000 flasks (San Jose, CA). Monoclonal antibodies to PRT/heparin were isolated using protein A (ProPur Midi A columns; ThermoFisher Scientific, Rochester, NY) columns according to the manufacturer’s instructions. KKO, an IgG2bκ antibody to PF4/heparin complexes, was developed in our laboratory as previously described.7 Isotype controls were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

ELISA studies

Binding of ADA to PRT/heparin or to PRT/low molecular weight complexes (enoxaparin or fondaparinux), mouse PF4/heparin, human PF4/heparin, or albumin was measured by ELISA as previously described.7 To determine the ability of antibodies to bind in the presence of excess heparin, patient-derived HIT antibodies (diluted 1:100) or patient-derived anti-PRT/heparin antibodies (diluted 1:500 or 1:2000) were incubated with increasing amounts of unfractionated heparin (0.1-100 U/mL) in 10% fetal bovine serum. Binding of antibodies was then measured by ELISA as previously described.8 GAGs were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (chondroitin sulfates A and C, dermatan sulfate, dextran sulfate [molecular weight 6500-10 000], and heparan sulfate). Binding of anti-PRT/heparin or anti-PF4/heparin antibodies to PRT/GAGs or PF4/GAGs was performed as previously described.7 Goat anti-human IgG γ-chain specific (Sigma) or goat anti-mouse IgG γ-chain specific (KPL, Gaithersburg, Maryland) labeled with horse radish peroxidase was used for secondary antibodies. Tetramethylbenzidine substrate (KPL) was used for colorimetric detection. Plates were read at 450 nm in a Molecular Devices ELISA plate reader (Sunnvale, CA).

Cell-associated ELISA

Cell-associated ELISA was performed using various cell lines (CHO and HUVEC, ATCC, or EA.hy926 endothelial cell line provided by Cora-Jean Edgell [University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill]) according to previously described methods.7 In brief, cells were grown to confluence in recommended media for each cell line. Cells were then seeded into 96-well microtiter plates (Nunc C96 Maxisorp; Thermo Scientific) at a density of 50 000 cells per well. Once confluent, cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) and incubated with antigen (PRT 31 μg/mL ± heparin 4 U/mL), and binding of monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies was measured by ELISA as described in the previous paragraph.

Statistical analysis

All data shown are representative of at least 3 independent determinations. Means and standard deviations or medians and ranges for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables were used to summarize data. Association of the continuous variables was examined using Spearman correlations because the variables are nonnormal. Statistical significance was examined at α = .05. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS statistical software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

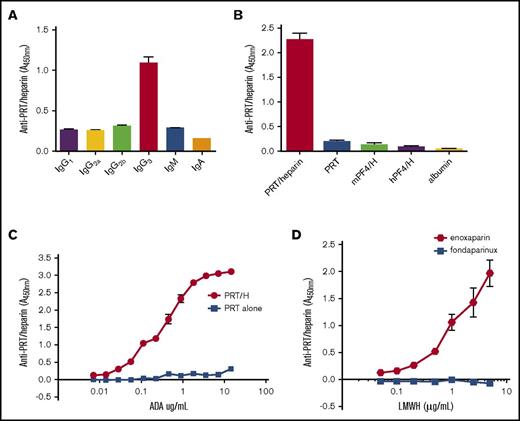

Development of murine monoclonal antibody to PRT/heparin complexes

We undertook these studies to examine the serologic and biologic characteristics of anti-PRT/heparin antibodies. Because patient-derived samples provide a finite resource, we developed an anti-PRT/heparin monoclonal antibody (ADA) using techniques previously described for the development of KKO, a monoclonal anti-PF4/heparin antibody.7 BALB/c mice injected with PRT/heparin complexes developed robust immune responses to PRT/heparin (data not shown). Splenocytes from 2 mice expressing high-titer anti-PRT/heparin antibodies were fused with an immortalized myeloma cell line, and a hybridoma with anti-PRT/heparin specificity was identified for cloning. This clone, named ADA, is a monoclonal IgG3κ (Figure 1A). ADA is highly specific for PRT/heparin because it does not recognize heparin bound to other positively charged proteins, such as human PF4 or mouse PF4, nor does it bind nonspecifically to other proteins, such as albumin (Figure 1B). ADA binds specifically to the PRT/heparin complex, and it is does not bind to PRT alone. Half-maximal binding of ADA was noted at 1.44 µg/mL. As shown in Figure 1C, ADA does not bind to PRT alone over a wide range of antibody concentrations tested (7 ng/mL to 14.4 µg/mL). To determine if ADA is able to bind to PRT complexed to low molecular weight heparin or fondaparinux, binding of ADA (49 ng/mL) was measured at a fixed concentration of PRT (31 µg/mL) along with varying concentrations of enoxaparin or fondaparinux (0-5 µg/mL). As seen in Figure 1D, binding of ADA increases with increasing enoxaparin concentration. In contrast, ADA does not recognize PRT/fondaparinux complexes at any concentration of fondaparinux tested. These studies show that the monoclonal antibody ADA is highly specific for PRT/heparin complexes, and it cross-reacts with PRT/enoxaparin complexes.

Characterization of a monoclonal antibody (ADA) to PRT/heparin complexes. (A) Isotype of ADA. ADA was confirmed to be an IgG3 subtype by an antigen-capture assay using isotype-specific antibodies as shown on the x-axis. (B) ADA specificity. ADA binding to PRT/heparin complexes, protamine alone (PRT), mouse PF4/heparin (mPF4/H) complexes, human PF4/heparin (hPF4/H) complexes, or albumin was measured by ELISA. Mean absorbance of triplicate wells at 450 nm is shown on the y-axis. (C) ADA binding to PRT/heparin complexes vs protamine alone. Serial dilutions of ADA were incubated in microtiter wells coated with PRT/heparin or protamine alone. Concentration of ADA is shown on the x-axis, and mean absorbance of triplicate wells is shown on the y-axis. Half-maximal binding of ADA to PRT/heparin complexes occurred at 1.44 µg/ml. (D) ADA binding to low molecular weight heparins (LMWHs). ADA binding to protamine/LMWH (enoxaparin or fondaparinux) complexes was determined by ELISA. Increasing concentration of enoxaparin or fondaparinux is shown along the x-axis.

Characterization of a monoclonal antibody (ADA) to PRT/heparin complexes. (A) Isotype of ADA. ADA was confirmed to be an IgG3 subtype by an antigen-capture assay using isotype-specific antibodies as shown on the x-axis. (B) ADA specificity. ADA binding to PRT/heparin complexes, protamine alone (PRT), mouse PF4/heparin (mPF4/H) complexes, human PF4/heparin (hPF4/H) complexes, or albumin was measured by ELISA. Mean absorbance of triplicate wells at 450 nm is shown on the y-axis. (C) ADA binding to PRT/heparin complexes vs protamine alone. Serial dilutions of ADA were incubated in microtiter wells coated with PRT/heparin or protamine alone. Concentration of ADA is shown on the x-axis, and mean absorbance of triplicate wells is shown on the y-axis. Half-maximal binding of ADA to PRT/heparin complexes occurred at 1.44 µg/ml. (D) ADA binding to low molecular weight heparins (LMWHs). ADA binding to protamine/LMWH (enoxaparin or fondaparinux) complexes was determined by ELISA. Increasing concentration of enoxaparin or fondaparinux is shown along the x-axis.

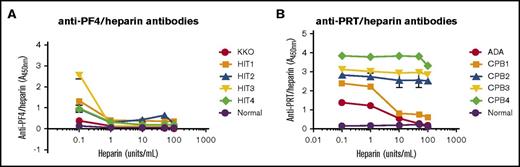

Heparin-dependent binding characteristics of anti-PRT/heparin and anti-PF4/heparin antibodies

HIT antibodies bind to antigen over a narrow range of heparin concentrations that coincide with formation of PF4/heparin ultralarge complexes (ULCs) at certain molar ratios.9-11 To determine if binding of ADA and patient-derived anti-PRT/heparin antibodies are also affected by the concentration of heparin present, we compared binding of monoclonal antibodies (KKO and ADA) and patient-derived antibodies (anti-PF4/heparin, n = 4; anti-PRT/heparin, n = 4) with their respective antigens in the presence of excess heparin (0.1-100 U/mL). HIT antibodies showed marked sensitivity to the presence of excess heparin, with significant loss of antigen binding at heparin concentrations >0.1 U/mL (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 1). In contrast, ADA and anti-PRT/heparin antibodies showed minimal loss of reactivity with excess heparin (Figure 2B). Further dilution of anti-PRT/heparin antibodies from 1:500 to 1:2000 did not significantly alter sensitivity to excess heparin (supplemental Figure 2). Together, these data show that unlike HIT antibodies, which are uniquely sensitive to excess heparin, binding of ADA and patient-derived anti-PRT/heparin antibodies are relatively insensitive to excess heparin, even at high dilutions of antibody.

Heparin-dependent reactivity of monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies to PF4/heparin and PRT/heparin complexes. (A) Binding of KKO and HIT antibodies to PF4/heparin in the presence of excess heparin. KKO 2 ng/mL, HIT antibodies from patients (HIT 1-4, diluted 1:100), or normal plasma (1:100) were incubated in microtiter wells coated with PF4/heparin complexes either in buffer or in buffer supplemented with increasing concentrations of unfractionated heparin (0.1-100 U/mL). Concentrations in excess of 0.1 U/mL of heparin were associated with significant loss of KKO and HIT antibody binding. (B) Binding of ADA and PRT/heparin antibodies to PRT/heparin in the presence of excess heparin. ADA 100 ng/mL, patient-derived PRT/heparin antibodies (CPB1-4, diluted 1:500), or normal plasma (1:500) were incubated in microtiter wells coated with PRT/heparin complexes either in buffer or buffer supplemented with increasing concentrations of unfractionated heparin (0.1-100 U/mL). For CPB1, antibody binding was reduced with heparin concentrations ≥ 10 U/mL (78% decrease in binding). CPB2-4 showed significant binding despite excess heparin (>100 U/mL). Binding characteristics of antibodies are also shown in columnar format in supplemental Figure 1. All data shown are representative of 3 independent determinations.

Heparin-dependent reactivity of monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies to PF4/heparin and PRT/heparin complexes. (A) Binding of KKO and HIT antibodies to PF4/heparin in the presence of excess heparin. KKO 2 ng/mL, HIT antibodies from patients (HIT 1-4, diluted 1:100), or normal plasma (1:100) were incubated in microtiter wells coated with PF4/heparin complexes either in buffer or in buffer supplemented with increasing concentrations of unfractionated heparin (0.1-100 U/mL). Concentrations in excess of 0.1 U/mL of heparin were associated with significant loss of KKO and HIT antibody binding. (B) Binding of ADA and PRT/heparin antibodies to PRT/heparin in the presence of excess heparin. ADA 100 ng/mL, patient-derived PRT/heparin antibodies (CPB1-4, diluted 1:500), or normal plasma (1:500) were incubated in microtiter wells coated with PRT/heparin complexes either in buffer or buffer supplemented with increasing concentrations of unfractionated heparin (0.1-100 U/mL). For CPB1, antibody binding was reduced with heparin concentrations ≥ 10 U/mL (78% decrease in binding). CPB2-4 showed significant binding despite excess heparin (>100 U/mL). Binding characteristics of antibodies are also shown in columnar format in supplemental Figure 1. All data shown are representative of 3 independent determinations.

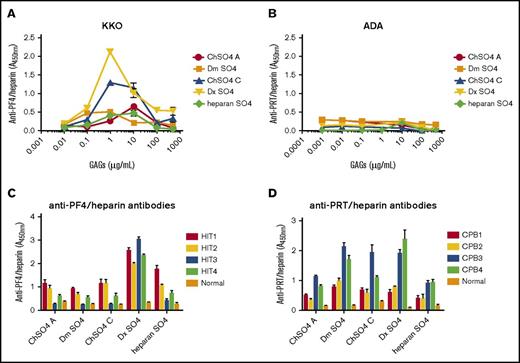

Binding of anti-PF4/heparin and anti-PRT/heparin antibodies to GAGs

It has long been recognized that other naturally occurring and/or synthetic GAGs can substitute for heparin in the PF4/heparin antigenic complex and promote cross-reactivity with HIT antibodies.12-14 To determine if anti-PRT/heparin antibodies similarly recognize PRT/GAG complexes, we performed cross-reactivity assays using complexes formed by PRT or PF4 with chondroitin sulfate A, chondroitin sulfate C, dermatan sulfate, dextran sulfate, or heparan sulfate. Consistent with prior observations, KKO showed binding to PF4/GAGs, with variable binding depending on GAG concentration and moiety (Figure 3A). Binding was most robust with complexes formed with 1 to 500 µg/mL dextran sulfate. In contrast, ADA showed no binding to PRT in complex with any GAG over a broad range of concentrations (0-500 µg/mL; Figure 3B). We next performed cross-reactivity studies with these same GAGs using patient-derived HIT antibodies (HIT1-4) and patient-derived anti-PRT/heparin antibodies (CPB1-4). We noted differential reactivity of anti-PRT/heparin and anti-PF4/heparin antibodies to their respective PRT/GAG and PF4/GAG complexes. HIT antibodies showed selective reactivity, because binding of HIT antibodies varied by patient, GAG concentration, and GAG moiety (Figure 3C). In contrast, patient-derived anti-PRT/heparin antibodies seemed to show a generally dichotomous pattern of binding, wherein patients showed either general binding (CPB3-4) or no binding (CPB1- 2; Figure 3D) to PRT/GAG complexes.

Binding of antibodies to PF4/GAGs or PRT/GAGs. (A) Binding of KKO to PF4/GAGs. KKO 2 ng/mL was incubated with microtiter wells coated with PF4 alone or with PF4/GAG complexes containing increasing concentrations (1 ng/mL to 500 µg/mL) of chondroitin sulfate (ChSO4 A or ChSO4 C), dermatan sulfate (Dm SO4), dextran sulfate (Dx SO4), or heparan sulfate (heparan SO4). (B) Binding of ADA to PRT/GAGs. Similar studies as shown in (A) were performed using ADA 50 ng/mL and wells coated with PRT or PRT/GAG complexes (1 ng/mL to 500 µg/mL). (C) Binding of HIT antibodies to PF4/GAGs. Patient-derived HIT antibodies (HIT1-4) or normal plasma were diluted 1:100 in wells coated with PF4/GAG complexes. Antibody binding to PF4/GAG 10 µg/mL is depicted. (D) Binding of PRT/heparin antibodies to PRT/GAGs. Patient-derived PRT/heparin antibody samples (CPB1-4) or normal plasma were diluted 1:2000 in wells coated with PRT/GAG complexes. Antibody binding to PRT/GAG 10 µg/mL is depicted. Polyclonal PRT/heparin antibodies displayed differential binding to PRT/GAG complexes. All data shown are representative of 3 independent determinations.

Binding of antibodies to PF4/GAGs or PRT/GAGs. (A) Binding of KKO to PF4/GAGs. KKO 2 ng/mL was incubated with microtiter wells coated with PF4 alone or with PF4/GAG complexes containing increasing concentrations (1 ng/mL to 500 µg/mL) of chondroitin sulfate (ChSO4 A or ChSO4 C), dermatan sulfate (Dm SO4), dextran sulfate (Dx SO4), or heparan sulfate (heparan SO4). (B) Binding of ADA to PRT/GAGs. Similar studies as shown in (A) were performed using ADA 50 ng/mL and wells coated with PRT or PRT/GAG complexes (1 ng/mL to 500 µg/mL). (C) Binding of HIT antibodies to PF4/GAGs. Patient-derived HIT antibodies (HIT1-4) or normal plasma were diluted 1:100 in wells coated with PF4/GAG complexes. Antibody binding to PF4/GAG 10 µg/mL is depicted. (D) Binding of PRT/heparin antibodies to PRT/GAGs. Patient-derived PRT/heparin antibody samples (CPB1-4) or normal plasma were diluted 1:2000 in wells coated with PRT/GAG complexes. Antibody binding to PRT/GAG 10 µg/mL is depicted. Polyclonal PRT/heparin antibodies displayed differential binding to PRT/GAG complexes. All data shown are representative of 3 independent determinations.

Binding of anti-PRT/heparin antibodies to PRT/dextran complexes is predictive of binding to cell-surface GAGs

Findings shown in Figure 3D demonstrated that anti-PRT/heparin antibodies can be differentiated into those that react (CPB3- 4) and those that do not react (CPB1-2) to PRT/GAGs. On the basis of this observation, we next asked if binding to PRT/GAGs in our assay correlates with ability to bind to cell-surface GAGs. To address this question, we used PRT/dextran as a representative GAG, given its low cost and commercial availability. To determine if binding to PRT/dextran correlates with binding to PRT bound to cell-surface GAGs, we examined the cross-reactivity of the 4 patients with CPB shown in Figure 3D with 3 differing cell lines (CHO, HUVEC, and EA.hy926 cells). As shown in Table 1, anti-PRT/heparin antibody binding to PRT/dextran seemed to correlate with binding to cell-surface–bound PRT in all cell lines tested. As depicted in Table 1, all 4 patients with CPB showed selective binding to PRT/heparin with minimal reactivity to PRT alone. In contrast, antibody binding to PRT/dextran differed among this cohort. Whereas CPB1 and CPB2 showed minimal binding to PRT/dextran, CPB3 and CPB4 were reactive to this antigen. These same patients also showed differential binding to PRT in association with cellular GAGs. Following the same overall binding pattern, CPB1 and CPB2 showed minimal binding to PRT/cell-surface GAG complexes, whereas CPB3 and CPB4 showed reactivity to PRT/GAGs on CHO, HUVEC, and EA.hy926 cell lines. In this limited cohort (n = 4), the binding of anti-PRT/heparin antibodies to dextran sulfate seemed to parallel antibody cross-reactivity to cellular GAGs.

Binding characteristics of patient-derived PRT/heparin antibodies (CPB1-4)

| CPB . | PRT/heparin . | PRT alone . | PRT/dextran . | CHO . | HUVEC . | EA.hy926 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.50 ± 0.09 | 0.17 ± 0.07 | 0.06 ± 0.002 | 0.54 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.07 | 0.25 ± 0.01 |

| 2 | 1.15 ± 0.09 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.33 ± 0.06 | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 0.21 ± 0.06 | 0.35 ± 0.03 |

| 3 | 1.50 ± 0.00 | 0.47 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.04 | 1.23 ± 0.02 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 1.26 ± 0.01 |

| 4 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 1.14 ± 0.22 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.73 ± 0.17 | 0.52 ± 0.08 |

| CPB . | PRT/heparin . | PRT alone . | PRT/dextran . | CHO . | HUVEC . | EA.hy926 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.50 ± 0.09 | 0.17 ± 0.07 | 0.06 ± 0.002 | 0.54 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.07 | 0.25 ± 0.01 |

| 2 | 1.15 ± 0.09 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.33 ± 0.06 | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 0.21 ± 0.06 | 0.35 ± 0.03 |

| 3 | 1.50 ± 0.00 | 0.47 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.04 | 1.23 ± 0.02 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 1.26 ± 0.01 |

| 4 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 1.14 ± 0.22 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.73 ± 0.17 | 0.52 ± 0.08 |

For each assay, reactivity (mean A450 nm ± standard deviation) is depicted. All data shown are representative of 3 independent determinations.

Strong correlation of antibody binding to PRT/dextran complexes and PRT bound to cell-surface GAGs

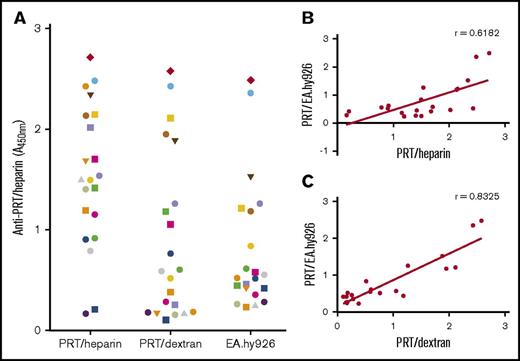

Building on the findings listed in Table 1, we next examined an expanded cohort of anti-PRT/heparin–seropositive patients (n = 21) to determine if binding to PRT/dextran could potentially discriminate a subpopulation of antibodies that react to cell-surface GAGs. For these studies, we used EA.hy926 cells as a representative cell line. Figure 4A shows the reactivity of an expanded cohort of CPB patients with anti-PRT/heparin antibodies to PRT/heparin, PRT/dextran, and PRT/EA.hy926 cells. Figure 4B-C shows the correlation of binding to each antigen plotted against binding to PRT/EA.hy926. We noted significant correlation between antibody binding to PRT/dextran and PRT/EA.hy926 cells (r = 0.8325; P < .0001). These findings indicate that reactivity of anti-PRT/heparin antibodies to PRT/dextran complexes can identify antibody subpopulations that react to cell-surface GAGs.

Binding of PRT/heparin antibodies to antigens and to EA.hy926 cells. (A) Binding of PRT/heparin antibodies to PRT/heparin complexes, PRT/dextran, or PRT/EA.hy926. Plasma from 21 patients with CPB containing PRT/heparin antibodies were diluted 1:2000 in microtiter wells coated with PRT/heparin or PRT/dextran 10 µg/mL. For cell-based studies, fixed EA.hy926 cells were incubated with PRT 31 µg/mL for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by CPB samples (n = 21) diluted 1:500. (B-C) Correlation of PRT/EA.hy926 binding. Binding of PRT/heparin antibodies (n = 21) to PRT/heparin complexes (B) or PRT/dextran 10 µg/mL (C) is plotted as a function of PRT/EA.hy926 binding. All data shown are representative of 2 independent determinations.

Binding of PRT/heparin antibodies to antigens and to EA.hy926 cells. (A) Binding of PRT/heparin antibodies to PRT/heparin complexes, PRT/dextran, or PRT/EA.hy926. Plasma from 21 patients with CPB containing PRT/heparin antibodies were diluted 1:2000 in microtiter wells coated with PRT/heparin or PRT/dextran 10 µg/mL. For cell-based studies, fixed EA.hy926 cells were incubated with PRT 31 µg/mL for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by CPB samples (n = 21) diluted 1:500. (B-C) Correlation of PRT/EA.hy926 binding. Binding of PRT/heparin antibodies (n = 21) to PRT/heparin complexes (B) or PRT/dextran 10 µg/mL (C) is plotted as a function of PRT/EA.hy926 binding. All data shown are representative of 2 independent determinations.

Discussion

Given the recent discovery of anti-PRT/heparin antibodies, there is limited information on the clinical and biologic specificities of this new class of heparin-dependent antibodies. In this report, we describe the serologic properties of anti-PRT/heparin antibodies and compare them with those of HIT antibodies, which are well characterized in the literature. Using a newly developed monoclonal antibody to PRT/heparin complexes (ADA), patient-derived anti-PRT/heparin antibodies, a HIT monoclonal antibody (KKO), and patient-derived HIT antibodies, we note distinctive serologic properties of these two classes of antibodies with respect to heparin dependence and binding to cellular GAGs. We additionally note that binding of anti-PRT/heparin antibodies to PRT/dextran complexes correlates with binding to PRT bound to the cell surface. These findings indicate that anti-PRT/heparin antibodies, unlike anti-PF4/heparin antibodies, which are causative of HIT, are relatively insensitive to excess heparin and can be segregated into distinct populations based on their reactivity to dextran and/or cell-surface GAGs.

The serologic features noted in this study offer insights into the heterogeneity of disease expression with anti-PRT/heparin antibodies. The unique heparin sensitivity of anti-PF4/heparin antibodies derives, in large part, from formation of ULCs at certain molar ratios, which are further stabilized through HIT antibody binding.15 These studies in HIT and related observations16,17 have shown that addition of excess heparin to ULCs leads to complex dissolution and loss of binding sites for KKO and/or HIT antibodies. As shown in Figure 2A, the requirements for ULC assembly manifest as a unique sensitivity to heparin, with loss of HIT antibody binding at higher concentrations of heparin. Anti-PRT/heparin antibodies, in contrast, do not show this heparin sensitivity in binding (Figure 2B), suggesting that binding may not require ULC formation. Prior studies have established that PRT, a highly cationic protein, and heparin form ULCs through charge-dependent interactions, which can be detected by a variety of biophysical methods.3,18 Like PF4/heparin ULCs, PRT/heparin complexes show heparin-dependent reactivity, with maximal size occurring at molar ratios (3:1) of the two compounds associated with charge neutralization.18 Prior studies from Bakchoul et al3 have demonstrated that protamine changes conformation when complexed to heparin, likely resulting in the exposure of neoepitopes on protamine.3 This conformational change in protamine is most pronounced with the initial introduction of heparin but is less prominent with increasing concentrations of heparin.3 In studies shown here, we note that ADA and patient-derived antibodies bind to PRT/heparin complexes over a wide range of heparin concentrations (0.1-100 U/mL), exceeding the minimal concentration needed to disrupt ULCs (>4 U/mL).18 Together, these observations suggest that neoepitopes for anti-PRT/heparin antibodies are sufficiently exposed when PRT/heparin complexes of any size form, and the addition of heparin beyond the optimal level needed for PRT/heparin ULC formation has little effect on the induction of neoepitopes on protamine and subsequent binding of antibodies.

The finding that PRT/heparin antibodies bind to antigen in states of heparin excess can be biologically relevant for seropositive patients undergoing cardiac surgery, who are exposed to PRT and high doses of heparin. One recent study noted that anti-PRT/heparin–seropositive patients who were re-exposed to PRT during cardiac surgery had increased protamine requirements relative to seronegative patients.4 These seropositive patients did not experience adverse clinical events in the immediate postoperative period. On the basis of our findings, one could speculate that despite high circulating levels of heparin, preserved recognition of antigen by anti-PRT/heparin antibodies could lead to enhanced clearance of antigen, which manifests clinically as increased protamine requirements.

Our studies also reveal important serologic properties of anti-PRT/heparin antibodies with regard to protein/GAG binding. Because the pathogenicity of HIT antibodies is, in large part, mediated by antibodies binding and recognizing antigen bound to cell-surface GAGs, we examined binding of anti-PRT/heparin antibodies to PRT in the presence of either purified or cell-surface GAGs. In agreement with previous descriptions,7,13 we noted that KKO bound to PF4 in association with cell-surface GAGs as well as with cells coated with PF4/heparin complexes (supplemental Figure 3A). In contrast, as shown in supplemental Figure 3B, ADA does not bind to cells incubated with PRT and only binds to cells incubated with PRT/heparin complexes. Patient-derived PRT/heparin antibodies, however, show variable binding to PRT/GAGs. As depicted in Table 1 and Figure 4A, we noted a seemingly dichotomous pattern of reactivity to cell-surface GAGs. Whereas a majority of patients showed minimal binding to PRT/GAGs, a subset of patients (6 [28%] of 21 patients) displayed strong binding to cell-surface GAGs (A450 nm > 1; Figure 4A). We also observed that antibody binding to PRT/dextran complexes correlates significantly with the ability of antibodies to bind to cell-surface GAGs (Figure 4C). Whether PRT/dextran binding can be used as a predictive measure of cell-surface binding requires further study with larger sample sets.

We speculate that antibody populations capable of recognizing PRT/GAG complexes are likely to exert functional activity in vitro, and possibly in vivo, given an appropriate context of antigen exposure. Because of limited patient sample volumes in this study, we were unable to correlate GAG-binding properties of anti-PRT/heparin antibodies with functional properties of antibodies in platelet activation or cellular activation assays. With ADA, we were unable to demonstrate platelet activation with PRT, with or without heparin (data not shown), an effect we attribute to the lack of PRT/GAG reactivity of ADA. However, our finding that ∼28% of anti-PRT/heparin antibodies recognize PRT/GAG complexes (Figure 4A) closely parallels findings reported in the literature of the prevalence of antibodies with functional activity in the presence of PRT alone. In a study of patients undergoing cardiac surgery, Bakchoul et al3 noted that 24 (15.6%) of 154 seropositive patients had anti-PRT/heparin antibodies capable of activating platelet in the presence of protamine alone. Pouplard et al1 found that ∼29% (17 of 59) of patients with anti-PRT/heparin antibodies had a positive serotonin release assay in the presence of PRT alone. Recently, Zollner et al19 noted that 21 (∼29%) of 80 sera containing anti-PRT/heparin bound to platelets in the presence of neutral protamine hagedorn insulin, but not in the presence of insulin alone, and that heparin dissociated antibody binding from platelets, implying that PRT was bound to cellular GAGs.

Whether the ability to bind to cellular GAGs is correlated with antibody pathogenicity remains unclear. In our limited cohort (n = 21), 6 patients showed PRT binding to PRT/EA.hy926, defined as absorbance at 450 nm > 1 (Figure 4A). Review of clinical information demonstrated that only 1 of these 6 patients developed an adverse outcome (right popliteal deep venous thrombosis and occlusion of a saphenous vein graft, both noted on postoperative day 10). The remaining 15 patients with non–GAG-binding antibodies experienced no adverse clinical outcomes. In additional analysis, we investigated the effect of binding to cell-surface GAGs on the development of postoperative thrombocytopenia. Platelet counts at baseline (before surgery) and on postoperative day 1 were queried for all patients. Patients with anti-PRT/heparin antibodies that bound to cell-surface GAGs had an absolute greater decrease in platelet count when compared with patients with antibodies that did not bind to cell-surface GAGs (mean [± standard deviation] change in platelet count of GAG binders, −44.42 ± 49.71 compared with non-GAG binders, −41.15 ± 59.5); however, these findings were not statistically significant (P = .8976). These results, however, do not imply that anti-PRT/heparin antibodies are inconsequential, because prior studies have demonstrated that anti-PRT/heparin antibodies are able to bind to protamine bound to cell-surface GAGs (PRT/GAG complexes) to elicit platelet activation in vitro and to manifest clinically as thrombocytopenia with bleeding.2,5 Thus, the broader clinical significance of anti-PRT/heparin antibodies with anti-PRT/GAG–binding properties awaits future prospective study. We believe that these studies will be facilitated by the use of protamine/dextran as a surrogate measure for detecting antibodies capable of binding to cell-surface GAGs.

In conclusion, our observations show several biologic differences between anti-PF4/heparin and anti-PRT/heparin antibodies that may provide insights into their respective clinical effects. These findings provide the framework for future studies to compare and contrast the role of antigenic ULCs in immune complex formation and cellular activation, contribution of GAG-binding antibodies to disease manifestations, and requirements for other cellular targets in disease pathogenesis.

Presented in part at the 56th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Francisco, CA, 6-9 December 2014.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Thomas Ortel and Sharon Hall at Duke University Medical Center for collaboration and for providing clinical samples from the HIT 5801 clinical study. The authors acknowledge Dayna Grant for her technical support.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grants HL110860 and HL109825 [G.M.A.] and K08HL127183 [G.M.L.]) and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant F32-AI108118-01) (G.M.L.).

Authorship

Contribution: G.M.L. and G.M.A. conceived and designed the study; G.M.L., S.K., and L.R. provided study materials or patients; G.M.L., M.J., S.K., and R.Q. collected and assembled data; G.M.L., M.J., S.K., L.R., G.M.A., and M.K. analyzed and interpreted data; G.M.L., M.J., G.M.A., and M.K. wrote the manuscript; and G.M.L., M.J., L.R., S.K., G.M.A., and M.K. provided final approval of manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Gowthami M. Arepally, Division of Hematology, DUMC Box 3486, Room 301, Alex H. Sands Building, Research Dr, Durham, NC 27710; e-mail: arepa001@mc.duke.edu.