Key Points

FAS-dependent apoptosis in Vδ1 T cells makes the latter possible culprits for the lymphadenopathy observed in patients with FAS mutations.

Rapamycin and methylprednisolone resistance should prompt clinicians to look for Vδ1 T cell proliferation in ALPS-FAS patients.

Introduction

Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) is a rare primary immune disease characterized by chronic nonmalignant, noninfectious lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and an increased likelihood of developing lymphoma or autoimmunity.1,2 The disease is caused by the lack of a functional interaction between FAS (CD95) and its ligand (FASL; CD95L). ALPS caused by mutations in FAS (ALPS-FAS) shows most often autosomal dominant inheritance. Although it has been suggested that the FAS genotype can influence genetic penetrance,3 it is still not known why disease severity varies markedly between individuals with identical mutations in FAS. It has been suggested that acquired somatic mutations and differential regulation of microRNAs affect disease penetrance.4-6 In contrast, it has yet to be demonstrated that environmental factors can influence penetrance.

Many patients with ALPS require immunosuppressive treatment, and it has been reported that corticosteroids, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclosporine A can alleviate autoimmune manifestations, albeit with variable outcomes.7,8 Another treatment, the antimalarial pyrimethamine, has been effective in reducing severe lymphadenopathy in some patients9,10 but not others.11 The search for alternative drug targets has revealed that the double-negative (DN) T cells’ proliferative activity is associated with hyperactive mechanistic target of rapamycin signaling.12 Thus, mechanistic target of rapamycin inhibition with rapamycin constitutes a more targeted pharmacological approach. This treatment indeed reduced lymphoproliferative and autoimmune manifestations in children with ALPS.13,14

It is probable that ALPS treatment outcomes are influenced by the type of cells involved in lymphoproliferation. The accumulation of T-cell receptor (TCR) αβ+ DN T cells in the peripheral blood is a unique feature and one of the diagnostic criteria of ALPS.4 Expansion of these cells in the lymph nodes has also been documented in some patients.15 Furthermore, γδ T cells are also found at higher frequencies in ALPS patients than in healthy individuals.15,16 It was previously shown that the majority of circulating γδ T cells in healthy individuals are restricted to the Vγ9Vδ2-TCR combination.17,18 However, tissue-resident γδ T cells are known to express other TCR combinations (with the predominance of Vδ1 over Vδ3). Adult and neonatal γδ T cells differ in several respects. During bacterial infections, Vδ2 T cells in adults accumulate in the peripheral blood, whereas Vδ1 T cells in newborns preferentially proliferate in the peripheral blood.19 The non–Vδ2 γδ T cells have also been found to expand during bacterial and viral infections, such as cytomegalovirus infections.20 As with αβTCRs, diversity at the TCRγ and TCRδ loci is generated by (1) somatic recombination of the V, D (other than in the γ chain), and J fragments; and (2) extensive modifications of the junction forming the complementary-determining region 3 (CDR3).21-23

Accumulation of γδ T cells in an enlarged cervical lymph node has previously been reported in a patient with ALPS-FAS.24 We now expand on this earlier report by detailing the TCR sequence repertoire in the lymph node of this patient and the lymph node of another patient with the same γδ-driven ALPS-FAS manifestations. Furthermore, we investigated how FASL-induced apoptosis controls the expansion of Vδ1 T cells. Finally, we analyzed the impact of current therapies for ALPS-FAS on the induction of apoptosis in γδ cells.

Case description

Patient 1 (Pt. 1)

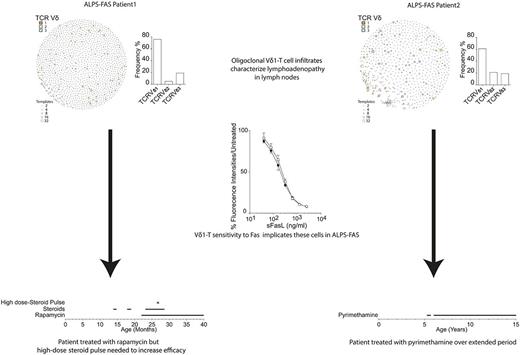

At 12 months of age, the male Pt. 1 presented with failure to thrive, mild fever, extensive splenomegaly (12 cm in length, as assessed with ultrasound imaging), generalized lymphadenopathy, bicytopenia (anemia and neutropenia), and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. The course of the disease in this patient is summarized in supplemental Figure 1. We arrived at a diagnosis of ALPS because Pt. 1 met the 2 requisite diagnostic criteria: (1) chronic, nonmalignant, noninfectious lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly; and (2) an elevated frequency of peripheral DN T cells (accounting for 17% of the CD45+ subset). Pt. 1 also met several of the secondary diagnostic criteria for ALPS: an elevated serum interleukin-10 level (>500 pg/mL at 12 months), polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, and a family history of nonmalignant/noninfectious lymphoproliferation. Even though serum vitamin B12 levels were normal at 12 months (1098 ng/mL), they were very high at 22 months (3942 ng/mL) and 31 months (3090 ng/mL).

Patient 2 (Pt. 2)

van den Berg et al have previously reported on Pt. 2’s clinical history between the ages of 1 and 6 months.24 Briefly, this female patient presented with splenomegaly, anemia, and thrombocytopenia at the age of 1 month. At 6 months, the patient developed cervical lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly. The size of the cervical lymph nodes fluctuated up to the age of 5 years, with enlargement during infections. The liver and (especially) the spleen were enlarged, whereas blood cell counts and serum immunoglobulin G levels were stable throughout the course of the disease.

Methods

Reported results are part of a large study of individuals with suspected primary immunodeficiencies registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (#NCT02735824). Methods can be found in supplemental Data.

Results and discussion

The 2 patients were found to carry different heterozygous mutations in FAS (supplemental Figure 1). However, both mutations were predicted to change the intracellular portion of FAS and therefore belong to a group of mutations associated with greater clinical penetrance and elevated rates of ALPS-related morbidity.3 Consistently, both mutations had a dominant-negative effect on apoptosis induced by recombinant FASL in cells sampled from the patients and from family members with the same mutation (supplemental Figure 2). Several symptoms of ALPS were observed (albeit to a lesser extent) in Pt. 2’s family members with the same mutation (data not shown). Similarly, Pt. 1’s mother carried the same mutation as her son and had a history of mild ALPS-like symptoms (sporadic lymphadenopathy; data not shown). Even though the clinical penetrance of the disease was high in both families, the severity and early onset in the index patients suggest the presence of a specific trigger or specific aggravating factors.

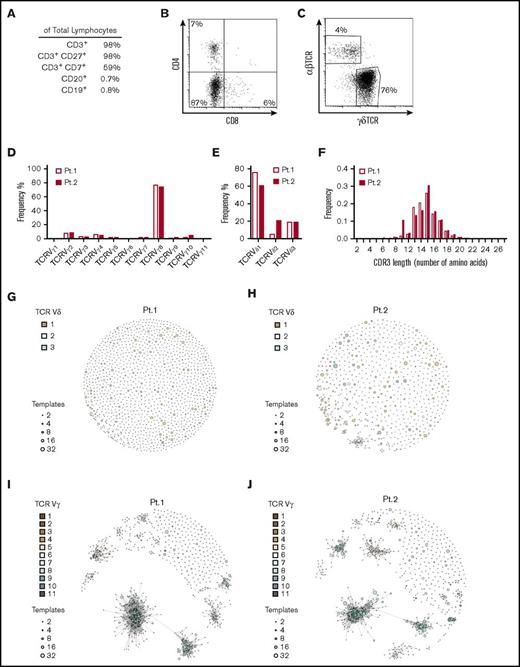

Pt. 1’s left inguinal lymph node was removed at the age of 12 months for diagnostic purposes. A histopathological analysis revealed infiltrates with expression of CD3, CD5, CD2, and CD7 but lacking CD4, CD8, and TCRβ (Figure 1A-B; supplemental Figure 3). Flow cytometry of suspensions from the same lymph node confirmed the cell population’s DN (CD4−CD8−) phenotype (Figure 1B) and indicated a γδTCR phenotype (Figure 1C). The results of a histopathological analysis of an enlarged cervical lymph node from Pt. 2 at the age of 6 months have been reported previously.24 In brief, the lymph node also contained an expanded CD3+CD4−CD8− γδ T cell population. Presence of additional (somatic) mutations in FAS was excluded by sequencing of DNA isolated from the same lymph nodes from both patients (supplemental Figure 4).

Lymphocytes isolated from lymph nodes express the Vγ8Vδ1-TCR. (A) Flow cytometry of cell suspension prepared from the left inguinal lymph node isolated from Pt. 1. Cell numbers are expressed as a percentage of total lymphocytes. (B) Flow cytometry on the same cell suspension but stained for CD4 and CD8 and gated on CD3+/CD45+ cells. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of γδTCR and αβTCR expression by CD3+/CD45+ cells present in the same inguinal lymph node. (D-E) Sequencing of recombined TCR genes in cells isolated from the lymph nodes from Pt. 1 (empty bars) and Pt. 2 (filled bars), showing Vγ and Vδ TCR chain usage. (F) The Vγ8 chain CDR3 length distribution in Pt. 1 (empty bars) and Pt. 2 (filled bars). (G-J) A network analysis for visualizing the sequences’ similarity, frequency, and level of homology. Each node in the network represents a sequence, and each color represents a different Vδ (G-H) or Vγ (I-J) chain. The size of each node is proportional to the frequency of the amino acid sequence. The level of homology between sequences is shown by the connecting lines.

Lymphocytes isolated from lymph nodes express the Vγ8Vδ1-TCR. (A) Flow cytometry of cell suspension prepared from the left inguinal lymph node isolated from Pt. 1. Cell numbers are expressed as a percentage of total lymphocytes. (B) Flow cytometry on the same cell suspension but stained for CD4 and CD8 and gated on CD3+/CD45+ cells. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of γδTCR and αβTCR expression by CD3+/CD45+ cells present in the same inguinal lymph node. (D-E) Sequencing of recombined TCR genes in cells isolated from the lymph nodes from Pt. 1 (empty bars) and Pt. 2 (filled bars), showing Vγ and Vδ TCR chain usage. (F) The Vγ8 chain CDR3 length distribution in Pt. 1 (empty bars) and Pt. 2 (filled bars). (G-J) A network analysis for visualizing the sequences’ similarity, frequency, and level of homology. Each node in the network represents a sequence, and each color represents a different Vδ (G-H) or Vγ (I-J) chain. The size of each node is proportional to the frequency of the amino acid sequence. The level of homology between sequences is shown by the connecting lines.

A CDR3 sequence analysis at the TCR-Vγ and TCR-Vδ loci of DNA isolated from the same lymph nodes revealed that in each patient, >75% of the cells expressed the TCR-Vγ8 chain (Figure 1D), and almost as many (>75% and >50% of the cells for Pt. 1 and Pt. 2, respectively) also expressed the TCR-Vδ1 chain (Figure 1E). This suggests that the vast majority of cells in the patients’ enlarged lymph nodes expressed the TCR-Vγ8Vδ1 chain combination. Analysis of the CDR3 amino acid sequence length evidenced polyclonal T-cell expansion in these lymph nodes (Figure 1F). A network analysis of sequence similarities revealed striking oligoclonal Vγ8 chain usage in both patients (Figure 1I-J), whereas the Vδ1 CDR3 sequence was polyclonal (Figure 1G-H). This common TCR-V chain usage pattern was not because of the expansion of cells bearing TCRs with common CDR3 sequences in both patients, because the most abundant γδTCR sequences were dissimilar (supplemental Tables 1-4). The oligoclonal TCR repertoire detected in both patients’ lymph nodes does not rule out the possibility whereby a common infectious agent gave rise to differences in the γδ T cells’ CDR3 sequences. For example, it has been shown that a single agent presented by butyrophilin BTN3A117 was responsible for the oligoclonal expansion of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. Nevertheless, it has been reported that intrauterine cytomegalovirus infections are associated with the enrichment of specific CDR3 sequences for Vγ8 and Vδ1.25 Furthermore, the expansion of Vδ1 T cells with restricted CDR3 sequences has been observed in systemic sclerosis,26 multiple sclerosis,27 HIV,28 and the small intestine and colon of healthy patients.29 All these CDR3 sequences were underrepresented in the TCR repertoire from our patients’ lymph nodes (supplemental Table 5). Furthermore, the 2 patients differed with regard to the most common Vδ1 sequences. The differences in the γδ CDR3 sequences between our 2 patients and the differences with regard to previously reported cases make it difficult to draw firm conclusions. The observed oligoclonal expansion suggests that FAS is essential in controlling non-Vδ2 T-cell expansion.

Repeated courses of oral prednisolone in Pt. 1 did not induce the long-term remission of cytopenia (supplemental Figure 5A). Oral rapamycin was initiated at the age of 23 months at a loading dose of 2 mg/m2, then reduced to 1 mg/m2, aiming for plasma levels of 2 to 10 ng/mL, reaching plasma levels of 2.5 to 12.3 ng/mL (initially measured weekly, then every 2-3 weeks, while the patient was receiving low-dose oral prednisolone) but had a limited effect. At 27 months, Pt. 1 (who was still on rapamycin) was given a 3-day course of high-dose IV methylprednisolone (10 mg/kg per day). Oral prednisolone was tapered off in the following 2 months. These interventions finally resulted in a reduction in spleen size and a return to normal hemoglobin levels (supplemental Figure 5A). The patient (now 3 years old) is still receiving rapamycin. He has mild splenomegaly and no lymphadenopathy. Pt. 2 is now 17 years old. She has been successfully treated with pyrimethamine since the age of 5 years (supplemental Figure 5B).

Based on these therapeutic outcomes, we designed a series of in vitro experiments to investigate (1) the role of FASL-mediated apoptosis on Vδ1 T cells and (2) the ability of rapamycin and pyrimethamine to induce death in Vδ1 T cells. These cells were found to express levels of FAS comparable to αβ T cells following phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) stimulation (Figure 2A). Incubation of the cell lines with increasing amounts of soluble FASL (sFASL) showed that Vδ1 and αβ T cells were equally sensitive to FAS-mediated apoptosis (Figure 2B-C). Pyrimethamine and rapamycin were also effective at inducing apoptosis, although rapamycin was more effective than pyrimethamine at lower concentrations, and Vδ1 cells were less sensitive than αβ T cells to both drugs (Figure 2B-C). In the same in vitro assay, Vδ1 T cells were found to be more resistant to the steroid methylprednisolone (Figure 2B).

Induction of apoptosis in vitro by FASL and drugs. (A) Expression of FAS on PHA-expanded Vδ1 (gray line) and αβ (black line) T-cell lines from healthy donors, compared with an isotype control (dashed line) and measured by flow cytometry. (B) The percentage of early apoptotic cells (annexin-V+ propidium iodide [PI]−) and late apoptotic cells (annexin-V+ PI+) in cultures of PHA-expanded Vδ1 (upper quadrants) and αβ (lower quadrants) T-cell lines from healthy donors when either untreated or following incubation with the indicated amounts of rapamycin, pyrimethamine, or sFASL for 4 hours. (C) Percentage fluorescence intensities (after incubation with AlamarBlue reagent) of PHA-expanded Vδ1 (empty circles) and αβ (filled circles) T-cell lines from healthy donors following exposure to the indicated amounts of rapamycin, pyrimethamine, sFASL, or methylprednisolone. The percentage fluorescence intensity was calculated as follows: (fluorescence of treated wells/fluorescence of untreated wells) × 100. Error bars indicate the standard deviation for 3 repeats. These data are representative of at least 2 repeats.

Induction of apoptosis in vitro by FASL and drugs. (A) Expression of FAS on PHA-expanded Vδ1 (gray line) and αβ (black line) T-cell lines from healthy donors, compared with an isotype control (dashed line) and measured by flow cytometry. (B) The percentage of early apoptotic cells (annexin-V+ propidium iodide [PI]−) and late apoptotic cells (annexin-V+ PI+) in cultures of PHA-expanded Vδ1 (upper quadrants) and αβ (lower quadrants) T-cell lines from healthy donors when either untreated or following incubation with the indicated amounts of rapamycin, pyrimethamine, or sFASL for 4 hours. (C) Percentage fluorescence intensities (after incubation with AlamarBlue reagent) of PHA-expanded Vδ1 (empty circles) and αβ (filled circles) T-cell lines from healthy donors following exposure to the indicated amounts of rapamycin, pyrimethamine, sFASL, or methylprednisolone. The percentage fluorescence intensity was calculated as follows: (fluorescence of treated wells/fluorescence of untreated wells) × 100. Error bars indicate the standard deviation for 3 repeats. These data are representative of at least 2 repeats.

Our findings show that lymphadenopathy in ALPS-FAS patients can be driven by the expansion of TCR Vγ8Vδ1 T lymphocytes. Our study is the first to demonstrate that Vδ1 T cells are sensitive to activation- induced cell death via FAS/FASL interaction. The biological relevance of these findings is evidenced by the report of 2 unrelated patients, each with a different germ line heterozygous FAS mutation, suffering from refractory ALPS with massive infiltration of γδT cells in secondary lymphoid organs. Remarkably, both patients underwent a special treatment program to induce remission from anemia and organomegaly. Thus, treatment failure, especially with regard to organomegaly in patients with ALPS should prompt clinicians to look for Vδ1 T cell proliferation.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Elaine Sarkin Jaffe and Stefania Pittaluga (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) for advice on the histopathological diagnosis. The authors also thank the patients and their families for their cooperation.

This work was supported by a grant from the Heidi-Ras Foundation (Zurich, Switzerland) and a grant from the Emily Dorothy Lagemann Foundation (Zurich, Switzerland) (S.V. and J.P.S.), a grant from the Müller-Gierok Foundation (Zurich, Switzerland) (A.M.), a Forschungskredit grant from the University of Zurich (Zurich, Switzerland) (U.N. and J.P.S.), and a grant from the Swiss Hochspezialisierte Medizin Schwerpunkt Immunologie program (B.V. and J.P.S.).

Authorship

Contribution: S.V. and J.P.S., conceived the research and wrote the manuscript with comments from all authors; S.V. performed the research; J.P.S. directed the laboratory work and clinical work for Pt. 1; F.R.-L. and B.N. actively contributed to drafting the manuscript; J.D.G. analyzed TCR sequencing data; J.T. and S.P. assisted with clinical work; A.v.d.B. supervised laboratory work on Pt. 2; R.Y.J.T. performed clinical work for Pt. 2; A.M.-C., O.P., U.N., A.M., B.V., O.S., B.R., U.C.G., D.R.Z., R.M., A.D., and L.V. contributed to research; L.S., L.O., and B.R. carried out sequencing and analyzed the results; and E.M.M. and E.H. performed all the histological assessments.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Stefano Vavassori, University Children’s Hospital Zurich, August-Forel Str 7, 8008 Zurich, Switzerland; e-mail: stefano.vavassori@kispi.uzh.ch.

![Figure 2. Induction of apoptosis in vitro by FASL and drugs. (A) Expression of FAS on PHA-expanded Vδ1 (gray line) and αβ (black line) T-cell lines from healthy donors, compared with an isotype control (dashed line) and measured by flow cytometry. (B) The percentage of early apoptotic cells (annexin-V+ propidium iodide [PI]−) and late apoptotic cells (annexin-V+ PI+) in cultures of PHA-expanded Vδ1 (upper quadrants) and αβ (lower quadrants) T-cell lines from healthy donors when either untreated or following incubation with the indicated amounts of rapamycin, pyrimethamine, or sFASL for 4 hours. (C) Percentage fluorescence intensities (after incubation with AlamarBlue reagent) of PHA-expanded Vδ1 (empty circles) and αβ (filled circles) T-cell lines from healthy donors following exposure to the indicated amounts of rapamycin, pyrimethamine, sFASL, or methylprednisolone. The percentage fluorescence intensity was calculated as follows: (fluorescence of treated wells/fluorescence of untreated wells) × 100. Error bars indicate the standard deviation for 3 repeats. These data are representative of at least 2 repeats.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/1/15/10.1182_bloodadvances.2017006411/3/m_advances006411f2.jpeg?Expires=1769221783&Signature=IGN31KQAku15IGXDdwUFg4D4ULRsaLGifDQ0-b3klGiiX0FwsNPd3WSft2acMhtgkOlq~Hfq~XqNR~Uizi3jPQOoEqbf-Orc4-99QCsJy6GaJWhGQUSiZVyMV0-IQkXc-fiT1Zv2ie079RMoBYDDuqWZdfCax1EbMjx0g2KQN97Vs8pj423eeImQCDQ6UQcSAwbOOtiQfGYPC2ZDtu76H3SOCkQgfquy76KcDq6uhHWti60DFWurP6jPI1Zay5VZ~Lc0mwH2Y4L-F0-li~-inU~X1lVF8mobyoSSjW3BtTIpYy5ICnp9SfCZY1i4J-gpvEDyS2jiatO~al0AC1XrYQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)