Key Points

We identify and characterize novel SF3B1 in-frame deletions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

These deletions are functionally similar to well-known SF3B1 hotspot mutations and are sensitive to splicing modulation.

Introduction

Hematologic neoplasms including myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, and acute myeloid leukemia have recently been reported to contain heterozygous hotspot mutations in splicing factor genes involved with 3′ splice site (ss) recognition (SF3B1, U2AF1, SRSF2, and ZRSR2).1-4 In contrast to other disorders, CLL is unique in that only SF3B1 is recurrently mutated.2 The spliceosome machinery directs the removal of introns from transcripts followed by ligation of coding exons during RNA splicing.5 The recently solved eukaryotic spliceosome structures indicate that SF3B1 HEAT domains interact with the branch site and polypyrimidine (Py) tract.6-8 Although the majority of SF3B1 hotspot mutations are located in the Py tract interacting region, the reason for inducing aberrant 3′ ss selection through reduced branch site fidelity remains unclear.9-13

The unique signature of aberrant 3′ ss junction usage by SF3B1 mutations suggests that these events can be used as biomarkers to discover additional genomic alterations that lead to similar splicing defects. To this end, we analyzed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) from 215 CLL patients. We discovered 3 patients carrying 2 novel SF3B1 in-frame deletions, and we demonstrate that these deletions induce aberrant 3′ ss selection through use of an alternative branch site, similar to SF3B1 p.K700E. In addition, patient samples carrying these deletions showed sensitivity to the splicing modulator E7107. Functionally, these novel deletions act similarly to other well-known SF3B1 hot-spot mutations suggesting patients carrying these lesions are candidates for treatment with SF3B1 modulators.

Case description

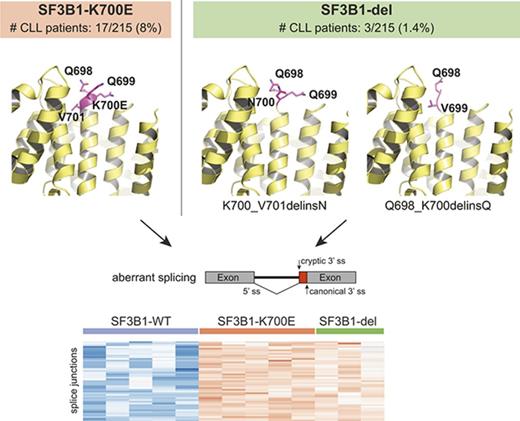

Recurrent mutations in RNA splicing factors SF3B1, U2AF1, and SRSF2 have been reported in hematologic cancers including MDSs and CLL. However, CLL is unique considering that only SF3B1 is found to be recurrently mutated and associated with aberrant splicing. To investigate whether other genomic aberrations cause similar splicing defects, we clustered RNA-seq data based on an alternative 3′ ss pattern previously identified in SF3B1-mutant CLL patients. Among 215 samples, we identified 37 (17%) with alternative 3′ ss usage, the majority of which harbored known SF3B1 hotspot mutations. Intriguingly, 3 patient samples carried previously unreported in-frame deletions in SF3B1 around K700, the most frequent mutation hot spot. To study the functional effects of these deletions, we used various minigenes demonstrating that recognition of canonical 3′ ss and alternative branch site are required for aberrant splicing, as observed for SF3B1 p.K700E. The common mechanism of action of these deletions and substitutions result in similar sensitivity of primary cells toward an SF3B1 splicing modulator. These data demonstrate a novel genomic aberration in SF3B1 that induces aberrant splicing and suggest SF3B1 in-frame deletions will confer sensitivity to splicing modulators.

Methods

RNA-seq from 215 CLL patients was analyzed to discover if any novel genomic abnormality was able to induce SF3B1-mutant-like aberrant splicing. Genomic abnormalities in 3 aberrant splicing cases were identified as SF3B1 in-frame deletions and confirmed in DNA by targeted resequencing. Analysis of RNA splicing was carried out as described previously.9 Expression of hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged mxSF3B1 deletion complementary DNAs transfected into HEK293FT cells was confirmed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and immunoblotting. Aberrant splicing was validated using ZDHHC16 minigenes and viability effect of E7107 in CLL primary cells was assessed by 3-(4,5 dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) assay. Methods in detail can be found in the supplemental Data.

Results and discussion

To investigate if genomic abnormalities in addition to known hot-spot mutations in SF3B1 led to SF3B1-mutant-like splicing aberrations in CLL patients, we clustered RNA-seq data from 215 samples based on previously identified SF3B1-mutant specific alternative 3′ ss in CLL (n = 194).9 Of 215 samples, we identified 37 (17%) with alternative 3′ ss usage, 34 of which harbored known SF3B1 hot-spot mutations including p.K700E. Interestingly, 3 patient samples carried previously unreported in-frame deletions in SF3B1: 1 patient had a 3 nucleotide (nt) deletion resulting in replacement of K700 and V701 with N (p.K700_V701delinsN, “p.K700del”) and 2 patients had 6 nt deletion resulting in replacement of Q698, Q699, and K700 with Q (p.Q698_K700delinsQ; “p.Q698del”) (Figure 1A). The SF3B1 deletion variant allele fraction (VAF) ranged from 8.8% to 42.2%, confirmed through RNA-seq and DNA sequencing. All 3 patients had poor prognostic features including unmutated IGHV status and high-risk cytogenetics (supplemental Table 1). Notably, a different SF3B1 in-frame deletion (p.Q699_K700del) has also been reported both in MDS14,15 and 2 cases of CLL16,17 ; however, its function remains uncharacterized.

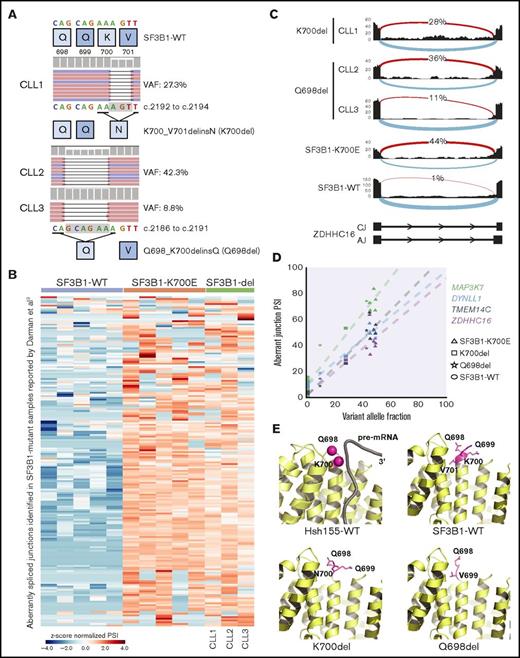

Novel SF3B1 in-frame deletions found in CLL patients result in aberrant splicing. (A) DNA sequencing reads from 3 CLL patients are aligned to show SF3B1 in-frame deletions: CLL1, p.K700_V701delinsN (p.K700del); CLL2 and CLL3, p.Q698_K700delinsQ (p.Q698del). The schematic below shows the 3 nt and 6 nt deletions resulting in replacement of K700 and V701 with N and of Q698, Q699, and K700 with Q, respectively. The deletion is highlighted in a gray box. (B) Heat map representing z score normalized percent spliced in (PSI) of aberrant junctions previously identified in SF3B1-mutant CLL patient samples (n = 194). Sample columns are grouped into SF3B1 variants: SF3B1 wild type (WT; n = 5), SF3B1 p.K700E (n = 5), and SF3B1 deletion mutants (n = 3). (C) Sashimi plot showing aberrant 3′ ss usage (red) with respect to canonical splicing (light blue) of ZDHHC16 exons 9 to 10 in different CLL patient samples: K700del (CLL1), Q698del (CLL2 and CLL3), SF3B1 p.K700E, and SF3B1 WT. The aberrant junction PSI is given as a percentage in each condition. For SF3B1 p.K700E and SF3B1 WT, the average read density and PSI is plotted (n = 5, each). (D) Four SF3B1 hotspot-specific aberrant ss’s show linear correlation between mutation allele frequency (%) and ss usage (PSI). Colors for splicing markers: light green, MAP3K7; light blue, DYNLL1; gray, TMEM14C; purple, ZDHHC16. Shapes for SF3B1 mutation status: circle, WT; triangle, p.K700E; square, p.K700del; star, p.Q698del. (E) Homology model based on cryo-electron microscopy structure of Hsh155 (SF3B1 homolog in yeast) interacting with pre–messenger RNA (pre-mRNA) near the deletion site (K700 and Q698 represented as magenta spheres, PDB: 5GM6) and crystal structure of apo-SF3B1 (PDB: 5IFE) are shown in top panel. Homology modeling of SF3B1 in-frame deletions, K700del and Q698del, based on the crystal structure (PDB: 5IFE) are shown in the bottom panel. The affected amino acid side chains are represented in stick (magenta), rest of the protein (yellow), and pre-mRNA (gray) in illustration.

Novel SF3B1 in-frame deletions found in CLL patients result in aberrant splicing. (A) DNA sequencing reads from 3 CLL patients are aligned to show SF3B1 in-frame deletions: CLL1, p.K700_V701delinsN (p.K700del); CLL2 and CLL3, p.Q698_K700delinsQ (p.Q698del). The schematic below shows the 3 nt and 6 nt deletions resulting in replacement of K700 and V701 with N and of Q698, Q699, and K700 with Q, respectively. The deletion is highlighted in a gray box. (B) Heat map representing z score normalized percent spliced in (PSI) of aberrant junctions previously identified in SF3B1-mutant CLL patient samples (n = 194). Sample columns are grouped into SF3B1 variants: SF3B1 wild type (WT; n = 5), SF3B1 p.K700E (n = 5), and SF3B1 deletion mutants (n = 3). (C) Sashimi plot showing aberrant 3′ ss usage (red) with respect to canonical splicing (light blue) of ZDHHC16 exons 9 to 10 in different CLL patient samples: K700del (CLL1), Q698del (CLL2 and CLL3), SF3B1 p.K700E, and SF3B1 WT. The aberrant junction PSI is given as a percentage in each condition. For SF3B1 p.K700E and SF3B1 WT, the average read density and PSI is plotted (n = 5, each). (D) Four SF3B1 hotspot-specific aberrant ss’s show linear correlation between mutation allele frequency (%) and ss usage (PSI). Colors for splicing markers: light green, MAP3K7; light blue, DYNLL1; gray, TMEM14C; purple, ZDHHC16. Shapes for SF3B1 mutation status: circle, WT; triangle, p.K700E; square, p.K700del; star, p.Q698del. (E) Homology model based on cryo-electron microscopy structure of Hsh155 (SF3B1 homolog in yeast) interacting with pre–messenger RNA (pre-mRNA) near the deletion site (K700 and Q698 represented as magenta spheres, PDB: 5GM6) and crystal structure of apo-SF3B1 (PDB: 5IFE) are shown in top panel. Homology modeling of SF3B1 in-frame deletions, K700del and Q698del, based on the crystal structure (PDB: 5IFE) are shown in the bottom panel. The affected amino acid side chains are represented in stick (magenta), rest of the protein (yellow), and pre-mRNA (gray) in illustration.

In order to confirm that all the splicing aberrations found in mutant SF3B1 were observed in the novel deletion mutants, we selected 5 CLL patient samples with high VAF SF3B1 p.K700E and compared the expression of various aberrant splicing markers (Figure 1B), including the aberrant 3′ ss in intron 9 of ZDHHC16 (Figure 1C). Interestingly, all 3 samples with SF3B1 in-frame deletions showed all the aberrant 3′ ss selections observed in the SF3B1-mutant patient samples, and we observed a direct correlation between VAF and 4 selected aberrant splicing biomarkers (Figure 1D).9,18,19 Collectively, this analysis strongly suggested that SF3B1 deletions acquire a neomorphic function similar to p.K700E. Structural modeling of the p.K700del and p.Q698del mutations in SF3B1 indicated they were located at the edge of α-helix of HEAT repeat domain 6, a region critical for pre-mRNA interaction (Figure 1E, top panel).6,7 Deletion of key residues in the loop region could eliminate charged side-chain interaction of lysine with pre-mRNA or restrain conformational change in SF3B1 superhelical HEAT repeats affecting RNA/protein interactions (Figure 1E, bottom panel).

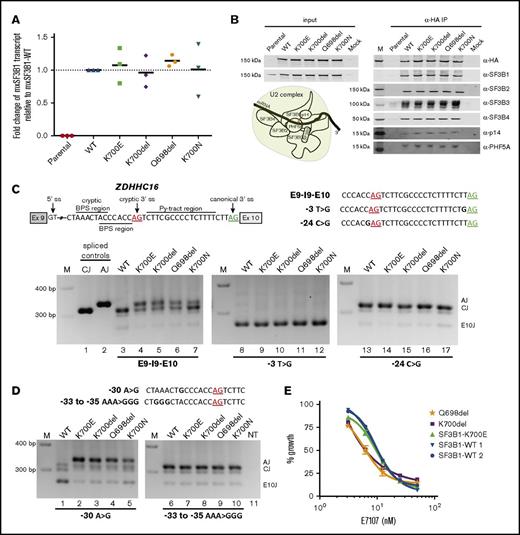

After confirming the expression of these SF3B1 in-frame deletions by qPCR and their incorporation in the core SF3b complex by coimmunoprecipitation (Figure 2A-B), we used ZDHHC16 minigenes to study the mechanism of induction of aberrant splicing.9 As expected, when Exon9-Intron9-Exon10 (E9-I9-E10) minigene was cotransfected with WT, only canonical splicing was observed (Figure 2C, lane 3), whereas in cells expressing p.K700del and p.Q698del and the hotspot mutations (p.K700E and p.K700N), both canonical and aberrant splicing were detected (lanes 4-7). Previously, through modifications in canonical 3′ ss, cryptic 3′ ss, branch sites, and Py tracts, we demonstrated that recognition of both canonical 3′ ss and alternate branch site are required for aberrant splicing of ZDHHC16 by SF3B1 hotspot mutants.9 To address the dependence of cryptic 3′ ss selection by the in-frame deletions on canonical 3′ ss, we altered the nucleotide base upstream of the AG dinucleotide (canonical, −3T>G; aberrant, −24C>G) that is critical for U2AF1 interaction.20 When −3T>G minigene was cotransfected with any of the constructs splicing was observed within exon 10 (Figure 2C, lanes 8-12). Whereas, when −24C>G minigene was used, only canonical splicing was observed in all cases (lanes 13-17), suggesting that the −3 position relative to cryptic AG is also important for its recognition during the second step of splicing. Further to test branch site utilization, we used ZDHHC16 minigenes with mutated branch sites (WT, −30A>G; mutant, −33 to −35 AAA>GGG). When −30A>G minigene was cotransfected with WT, splicing was observed within exon 10 (Figure 2D, lane 1), but when cotransfected with p.K700E or in-frame deletions, only aberrant splicing was observed (Figure 2D, lanes 2-5). When −33 to −35 AAA>GGG minigene was cotransfected with p.K700E or in-frame deletions, only canonical splicing was observed (Figure 2D, lanes 7-10). Taken together, these data show that the novel SF3B1 in-frame deletions p.K700del and p.Q698del use intronic features to induce aberrant splicing identical to the most frequent hotspot mutant p.K700E.

Expression and functional characterization of SF3B1 in-frame deletions. (A) Fold change of mxSF3B1 variant transcript relative to WT (calculated as 2−ΔΔCT) in HEK293FT cells transfected with mxSF3B1 WT, K700E, K700del, Q698del, and K700N complementary DNA constructs. Data are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean, n = 3. (B) Incorporation of SF3B1 variants in SF3b complex is shown through western blot analysis of 5 different complex partners after coimmunoprecipitation using α-HA beads. Input cell lysates are shown in the left panel, and the eluted IP samples are shown in the right panel. Schematic of SF3b in U2 complex is also shown with pre-mRNA branch site labeled as “A.” (C-D) Schematic of ZDHHC16 minigene labeled with ss’s is shown with cryptic AG (red) and canonical AG (green) underlined. Total RNA isolated from HEK293FT cotransfection of mxSF3B1 variants (WT, K700E, K700del, Q698del, K700N) with any of the 3 different ZDHHC16 minigenes (E9-I9-E10, −3T>G, −24C>G) (C) or with any of the 2 different ZDHHC16 minigenes (−30A>G, −33 to −35 AAA>GGG) (D) was used for reverse transcription PCR and visualized by ethidium-bromide stained 2.5% agarose gel. Sequences of different minigenes with specific mutations highlighted in bold are shown for respective gels. Spliced controls of canonical (CJ) and aberrant junction (AJ) are in lanes 1 and 2, marker is denoted as M, and nontransfected control is shown as NT. Spliced product for junction in exon 10 is shown as E10J. (E) Effects of splicing inhibitor E7107 treatment on viability of primary CLL patient cells (K700del, Q698del, SF3B1-K700E, SF3B1-WT 1, and SF3B1-WT 2) measured through MTS assay. E7107 concentration is plotted in log scale in the x-axis; % absorbance in the colorimetric assay is represented as % growth in the y-axis. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation, n = 3.

Expression and functional characterization of SF3B1 in-frame deletions. (A) Fold change of mxSF3B1 variant transcript relative to WT (calculated as 2−ΔΔCT) in HEK293FT cells transfected with mxSF3B1 WT, K700E, K700del, Q698del, and K700N complementary DNA constructs. Data are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean, n = 3. (B) Incorporation of SF3B1 variants in SF3b complex is shown through western blot analysis of 5 different complex partners after coimmunoprecipitation using α-HA beads. Input cell lysates are shown in the left panel, and the eluted IP samples are shown in the right panel. Schematic of SF3b in U2 complex is also shown with pre-mRNA branch site labeled as “A.” (C-D) Schematic of ZDHHC16 minigene labeled with ss’s is shown with cryptic AG (red) and canonical AG (green) underlined. Total RNA isolated from HEK293FT cotransfection of mxSF3B1 variants (WT, K700E, K700del, Q698del, K700N) with any of the 3 different ZDHHC16 minigenes (E9-I9-E10, −3T>G, −24C>G) (C) or with any of the 2 different ZDHHC16 minigenes (−30A>G, −33 to −35 AAA>GGG) (D) was used for reverse transcription PCR and visualized by ethidium-bromide stained 2.5% agarose gel. Sequences of different minigenes with specific mutations highlighted in bold are shown for respective gels. Spliced controls of canonical (CJ) and aberrant junction (AJ) are in lanes 1 and 2, marker is denoted as M, and nontransfected control is shown as NT. Spliced product for junction in exon 10 is shown as E10J. (E) Effects of splicing inhibitor E7107 treatment on viability of primary CLL patient cells (K700del, Q698del, SF3B1-K700E, SF3B1-WT 1, and SF3B1-WT 2) measured through MTS assay. E7107 concentration is plotted in log scale in the x-axis; % absorbance in the colorimetric assay is represented as % growth in the y-axis. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation, n = 3.

To examine the sensitivity of these novel SF3B1 deletions to pharmacologic splicing modulation in comparison with p.K700E, we used the splicing modulator E7107 known to cross-link the SF3b complex.21 An MTS assay on primary leukemia cells from CLL patients after treatment with E7107 showed a dose response similar to SF3B1K700E and SF3B1WT cells (IC50 of ∼4-10 nM; Figure 2E). This suggests that SF3B1 deletions discovered in this study may be therapeutically sensitive targets for splicing modulators. Indeed, an orally available SF3B1 modulator is currently being evaluated in phase 1 clinical trials (www.clinicaltrials.gov; #NCT02841540).

Here we report the identification, characterization, and sensitivity to splicing modulation of 2 novel SF3B1 in-frame deletions found in CLL. The colocalization of p.K700E hotspot mutation and these novel deletions highlight the functional importance of this region in SF3B1. These findings for SF3B1 are analogous to functionally similar oncogenic in-frame deletions that have been described surrounding hotspot mutations in the splicing factor SRSF2,3 and several oncogenes such as CTNNB1 and NFE2L2, encoding oncoproteins β-catenin and NRF2, respectively.22-25 Although the novel SF3B1 deletions we report here could compromise the superhelical flexibility and constitutively force an alternative conformation inducing changes in the protein-RNA interactome, they still induce aberrant splicing and maintain sensitivity toward splicing modulation, thus rendering them as therapeutic targets for treating spliceosome-mutant cancers.

The RNA-sequencing data analyzed and presented in this article have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE95352). The DNA-sequencing data analyzed and presented in this article have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (accession number SRP100874).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to patients and families for participating in clinical trials and providing samples; the authors also thank H3 Biomedicine employees for their support in this project.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Alliance Foundation for Clinical Trials in Oncology (J.S.B.) and the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (grants K23 CA178183 [J.A.W.] and R35 CA197734-01 [J.C.B.]).

Authorship

Contribution: M.S. and L.Y. conducted the bioinformatics analyses of RNA-seq data; A.A.A. performed the structure modeling, qPCR, immunoblotting, and minigene assays; R.M. prepared sequencing experiments; L.T.B. performed viability assays; J.S.B. and R.L. collected and analyzed viability experiment in patient samples; A.J.J., J.A.W., and J.C.B. provided reagents and patient samples; M.W., P.G.S., A.A.A., M.S., L.Y., J.S.B., and S.B. guided the experiments; A.A.A., M.S., J.S.B., and S.B. wrote the manuscript; and all authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.A.A., M.S., M.W., P.Z., L.Y., P.G.S., and S.B. are full time employees of H3 Biomedicine, Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Silvia Buonamici, H3 Biomedicine, Inc., 300 Technology Sq, Cambridge, MA 02139; e-mail: silvia_buonamici@h3biomedicine.com.

References

Author notes

A.A.A. and M.S. contributed equally to this study.

J.S.B. and S.B. are joint senior authors.