Key Points

Proteasomal HSP70 degradation results in cleavage of GATA1, decrease in erythroid progenitors, and apoptosis in severe DBA phenotype.

HSP70 plays a role not only during terminal erythroid differentiation, but also in the earlier proliferation of erythroid progenitor cells.

Abstract

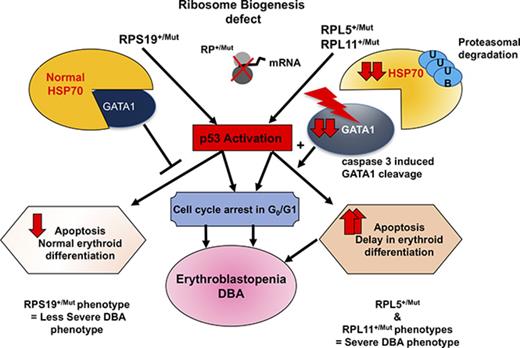

Diamond-Blackfan anemia (DBA) is a rare congenital bone marrow failure syndrome that exhibits an erythroid-specific phenotype. In at least 70% of cases, DBA is related to a haploinsufficient germ line mutation in a ribosomal protein (RP) gene. Additional cases have been associated with mutations in GATA1. We have previously established that the RPL11+/Mut phenotype is more severe than RPS19+/Mut phenotype because of delayed erythroid differentiation and increased apoptosis of RPL11+/Mut erythroid progenitors. The HSP70 protein is known to protect GATA1, the major erythroid transcription factor, from caspase-3 mediated cleavage during normal erythroid differentiation. Here, we show that HSP70 protein expression is dramatically decreased in RPL11+/Mut erythroid cells while being preserved in RPS19+/Mut cells. The decreased expression of HSP70 in RPL11+/Mut cells is related to an enhanced proteasomal degradation of polyubiquitinylated HSP70. Restoration of HSP70 expression level in RPL11+/Mut cells reduces p53 activation and rescues the erythroid defect in DBA. These results suggest that HSP70 plays a key role in determining the severity of the erythroid phenotype in RP-mutation–dependent DBA.

Introduction

A genetic defect in ribosome biogenesis1 has been noted in a variety of hematologic cancers,2-4 congenital asplenia,5 and congenital bone marrow failure syndromes including Shwachman-Diamond syndrome,6 dyskeratosis congenita,7 and Diamond-Blackfan anemia (DBA).8-11

DBA was the first identified human ribosomopathy.12 A constitutive heterozygous mutation, including large deleterious deletions,13-15 in 14 ribosomal protein (RP) genes13,16-23 is identified in 70% of DBA cases. The disease is characterized by an erythroblastopenia in an otherwise normocellular and nondysplastic bone marrow. The consequence is an anemia (often macrocytic) with reticulocytopenia. The erythroid maturation blockade in humans has been established to occur between the burst forming unit–erythroid (BFU-E) and colony forming unit–erythroid (CFU-E) stages.24 Erythroblastopenia is the unique clinical feature of 60% of DBA cases while being associated with diverse congenital abnormalities in the other patients.25-27 A few DBA patients who do not carry a mutation in 1 of the identified RP genes have been found to have mutations in the GATA1 gene, inducing a constitutive loss of the transactivation domain of this transcription factor.28-32

The reason why haploinsufficiency in some RP genes specifically affects erythropoeisis remains poorly understood. Identification of a translational defect of GATA1 messenger RNA (mRNA) suggests that abnormal expression of this transcription factor may account for the erythroid tropism of DBA.31 Abnormal GATA1 expression could also be the consequence of the downregulation of a key chaperone of GATA1, heat shock protein 70 (HSP70).33 Upon erythropoietin (EPO) stimulation, erythroblast differentiation requires caspase-3 activation and HSP70 migrates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus to protect GATA1 from caspase-3 mediated cleavage, which would inhibit the terminal erythroid differentiation process and induce apoptosis of erythroblasts.34 A defective relocalization of HSP70 to the nucleus of EPO-stimulated erythroblasts during terminal erythroid differentiation of proerythroblasts is known to be involved in the pathogenesis of anemia in some myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs)35 and in β-thalassemia.36

Using primary human cells and cultured cells, we have previously identified 2 distinct DBA phenotypes in RP-deficient patients. RPS19 haploinsufficiency decreases erythroid proliferation without affecting erythroid differentiation. In marked contrast, haploinsufficiency of RPL5 or RPL11 dramatically affects erythroid cell proliferation and induces apoptosis of erythroid cells.37 Given that HSP70 is involved in both erythroid differentiation and cell survival, we hypothesized that HSP70 may play a major role in the erythroblastopenia of DBA and may explain the variability in the observed phenotypes. Indeed, we found that the differential regulation of HSP70 expression during erythropoiesis can account for these 2 distinct phenotypes. More specifically, an abnormal degradation of HSP70 in erythroid progenitors was detected in haploinsufficient RPL5 or RPL11 primary human erythroid cells, but not in RPS19 haploinsufficient progenitor cells. These findings imply that HSP70 plays a role not only during terminal erythroid differentiation but also in the proliferation of erythroid progenitor cells.

Material and methods

Study population

A total of 12 patients affected with DBA, registered in the French DBA registry (CNIL acceptance no. 911387, CCTIRS no. 11.295, 5 December 2011), and 12 hematologically normal individuals were studied. DBA was diagnosed according to established criteria.27 Table 1 shows the biological and clinical data of the DBA patients. Human umbilical cord blood was collected from normal full-term deliveries after maternal informed consent according to approved institutional guidelines (Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris, Paris, France).

Description of the 12 DBA-affected patients who have been analyzed in this study

| DBA patients . | Sex . | Age* (mo) . | Hb* g/dL . | Reticulocyte count,* ×109/L . | eADA activity . | Mutated gene . | Malformations . | Treatment* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UPN#987 | F | 2 | 4.2 | 2 | NA | RPS19 | Yes | T |

| Thumb anomaly | ||||||||

| UPN#251 | F | 6 | NA | NA | NA | RPS19 | No | TI |

| UPN#35 | F | 3 | 5.6 | NA | Increased | RPS19 | Yes | T |

| Hair anomaly | ||||||||

| Prognathism | ||||||||

| UPN#37 | M | 3 | 2.9 | 90 | Normal | RPS19 | No | T |

| UPN#412 | M | 2 | 7 | NA | Increased | RPL5 | Supernumerary thumb | TI |

| Hypoplasic thumb | ||||||||

| Flat thenar | ||||||||

| UPN#587 | M | Birth | 9.5 | 15 | Increased | RPL11 | Yes | S |

| Spina bifida | ||||||||

| Triphalangeal thumb | ||||||||

| Arnold Chiari | ||||||||

| UPN#172 | F | Birth | 4.5 | 23 | Increased | RPL11 | No | T |

| UPN#189 | F | 4 | 11.9 | 23 | Increased | RPL11 | Yes | S |

| Thumb anomaly | ||||||||

| UPN#1130 | M | NA | NA | NA | Increased | RPL11 | Yes | TI |

| Thumb anomaly | ||||||||

| Ear anomaly | ||||||||

| Surdity | ||||||||

| Ectopia testis | ||||||||

| UPN#479 | M | Birth | 6 | NA | Increased | RPL11 | Yes | T |

| Prematurity | ||||||||

| Triphalangeal thumb | ||||||||

| Hypospadias | ||||||||

| Heart malformation | ||||||||

| UPN#1099 | M | 1 | 6.4 | 9 | Increased | RPL11 | Yes | T |

| Hypoacousia | ||||||||

| Eye anomaly | ||||||||

| Multiple naevi | ||||||||

| UPN#412 | M | 2 | 7 | NA | Increased | RPL11 | Supernumerary thumb | TI |

| Hypoplasic thumb | ||||||||

| Flat thenar |

| DBA patients . | Sex . | Age* (mo) . | Hb* g/dL . | Reticulocyte count,* ×109/L . | eADA activity . | Mutated gene . | Malformations . | Treatment* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UPN#987 | F | 2 | 4.2 | 2 | NA | RPS19 | Yes | T |

| Thumb anomaly | ||||||||

| UPN#251 | F | 6 | NA | NA | NA | RPS19 | No | TI |

| UPN#35 | F | 3 | 5.6 | NA | Increased | RPS19 | Yes | T |

| Hair anomaly | ||||||||

| Prognathism | ||||||||

| UPN#37 | M | 3 | 2.9 | 90 | Normal | RPS19 | No | T |

| UPN#412 | M | 2 | 7 | NA | Increased | RPL5 | Supernumerary thumb | TI |

| Hypoplasic thumb | ||||||||

| Flat thenar | ||||||||

| UPN#587 | M | Birth | 9.5 | 15 | Increased | RPL11 | Yes | S |

| Spina bifida | ||||||||

| Triphalangeal thumb | ||||||||

| Arnold Chiari | ||||||||

| UPN#172 | F | Birth | 4.5 | 23 | Increased | RPL11 | No | T |

| UPN#189 | F | 4 | 11.9 | 23 | Increased | RPL11 | Yes | S |

| Thumb anomaly | ||||||||

| UPN#1130 | M | NA | NA | NA | Increased | RPL11 | Yes | TI |

| Thumb anomaly | ||||||||

| Ear anomaly | ||||||||

| Surdity | ||||||||

| Ectopia testis | ||||||||

| UPN#479 | M | Birth | 6 | NA | Increased | RPL11 | Yes | T |

| Prematurity | ||||||||

| Triphalangeal thumb | ||||||||

| Hypospadias | ||||||||

| Heart malformation | ||||||||

| UPN#1099 | M | 1 | 6.4 | 9 | Increased | RPL11 | Yes | T |

| Hypoacousia | ||||||||

| Eye anomaly | ||||||||

| Multiple naevi | ||||||||

| UPN#412 | M | 2 | 7 | NA | Increased | RPL11 | Supernumerary thumb | TI |

| Hypoplasic thumb | ||||||||

| Flat thenar |

eADA, erythrocyte adenosine deaminase; F, female; Hb, hemoglobin; M, male; NA, not available; S, steroid; T, transfusion dependence; TI, therapeutic independence.

At diagnosis.

Cell culture

Cell lines.

The UT-7–EPO (gift from Komatsu laboratory, Japan) and EBNA 293T cells were cultured as previously described.37

Culture of human primary cells.

CD34+ cells isolated from the peripheral blood of DBA patients or controls or from human cord blood were cultured as previously described.37 In some of the studies, to ensure better cell synchronization during cell culture, we used a culture media developed at the New York Blood Center.38 Viable cells were counted in triplicate using the trypan blue dye exclusion test as a function of time in culture.

Erythroid differentiation and apoptosis

Sorting of erythroid cells at BFU-e and CFU-e stages.

As synchronization of erythroid cells is required to compare the relative protein levels at a specific stage of differentiation, we sorted cells according to an established method.38

Erythroid differentiation.

Erythroid differentiation was evaluated by flow cytometry from D5 to D14 using several antibodies: PC7- or phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated CD34 (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA), allophycocyanin-CD36 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), PE/Cy7-IL-3R (Miltenny, Paris, France), Glycophorin A (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), allophycocyanin-Band 3 (New York Blood Center, New York, NY), and PE-α4 integrin (Miltenny).

Apoptosis analysis.

For determining apoptosis, cells were stained with PerCP 5.5-Annexin V and with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis was conducted on a BD Biosciences flow cytometer. Data were analyzed using Kaluza software (Beckman Coulter).

Lentivirus generation and infection

Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) constructs targeting RPS19, RPL5, and RPL11 have been previously generated and validated by our group.37 HSP70 wild-type complementary DNA (cDNA) sequence was derived from the work of Frisan et al.35 We modified the pTRIP zephyr–PGK-EGFP-WPRE (gift from Michaela Fontenay, Cochin Institute, Paris, France) with a m-Cherry reporter sequence instead of an EGFP sequence for cell sorting of the positive cells for both GFP and m-Cherry. Lentivirus production, titration, and infection were done as previously described.37

For rescue experiments, erythroid cells were cotransduced with shRNAs targeting ribosomal proteins with either the pTRIP-ZEPHYR-mCherry control, or the pTRIP-ZEPHYR-HSP70-mCherry, which contains the wild-type HSP70 cDNA.

qRT-PCR

Method, primers, and internal probes used for quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) are described in Table 2.

Primers and probes

| Primers and probes studied . | Primer and probe sequences . |

|---|---|

| TaqMRPS19F | TGGTGGAAAAGGACCAAGATG |

| TaqMRPS19R | CCGGCGATTCTGTCCAGAT |

| ProbeRPS19 | CCGCAAACTGACACCTCAGGGACA |

| TaqMRPL5F | CTGTGGATGGAGGCTTGTC |

| TaqMRPL5R | CATTAAATTCCTTGCTTTCAGAATCA |

| Probe RPL5 | ATCCCTCACAGTACCAAACGATTCCCTGG |

| TaqMRPL11F | TTGGTATCTACGGCCTGGACTT |

| TaqMRPL11R | GATTCTGTGTTTGGCCCCAAT |

| ProbeRPL11 | TTTCAGCATCGCAGACAAGAAGCGC |

| TaqMhup53F | TTTGCGTGTGGAGTATTTGGAT |

| TaqMhup53R | TGTAGTGGATGGTGGTACAGTCAGA |

| ProbeHup53 | CACTTTTCGACATAGTGTGGTGGTGCCCTA |

| TaqMHSP70huF | ACATGAAGCACTGGCCTTTC |

| TaqMHSP70huR | CTCGGCGATCTCCTTCATCT |

| ProbehuHSP70 | AGCTCACCTGCACCTTGGGCT |

| TaqMhuGATA1F | CCTCATCCGGCCCAAGA |

| TaqMhuGATA1R | TGGTCGTCTGGCAGTTGGT |

| ProbeGATA1hu | TGATTGTCAGTAAACGGGCAGGTAC |

| TaqMhuGAPDHF | CCTGTTCGACAGTCAGCCG |

| TaqMhuGAPDHR | CGACCAAATCCGTTGACTCC |

| ProbeGAPDHhu | AGCCACATCGCTCAGACACCATGG |

| TaqMHPRThuF | GGCAGTATAATCCAAAGATGGTCAA |

| TaqMHPRThuR | TCAAATCCAACAAAGTCTGGCTTATAT |

| ProbeHPRThu | CTTGCTGGTGAAAAGGACCCCACGA |

| TaqMB2MhF | GCGGCATCTTCAAACCTCC |

| TaqMB2MhR | TGACTTTGTCACAGCCCAAGATA |

| ProbeB2Mh | TGATGCTGCTTACATGTCTCGATCCCACTT |

| Primers and probes studied . | Primer and probe sequences . |

|---|---|

| TaqMRPS19F | TGGTGGAAAAGGACCAAGATG |

| TaqMRPS19R | CCGGCGATTCTGTCCAGAT |

| ProbeRPS19 | CCGCAAACTGACACCTCAGGGACA |

| TaqMRPL5F | CTGTGGATGGAGGCTTGTC |

| TaqMRPL5R | CATTAAATTCCTTGCTTTCAGAATCA |

| Probe RPL5 | ATCCCTCACAGTACCAAACGATTCCCTGG |

| TaqMRPL11F | TTGGTATCTACGGCCTGGACTT |

| TaqMRPL11R | GATTCTGTGTTTGGCCCCAAT |

| ProbeRPL11 | TTTCAGCATCGCAGACAAGAAGCGC |

| TaqMhup53F | TTTGCGTGTGGAGTATTTGGAT |

| TaqMhup53R | TGTAGTGGATGGTGGTACAGTCAGA |

| ProbeHup53 | CACTTTTCGACATAGTGTGGTGGTGCCCTA |

| TaqMHSP70huF | ACATGAAGCACTGGCCTTTC |

| TaqMHSP70huR | CTCGGCGATCTCCTTCATCT |

| ProbehuHSP70 | AGCTCACCTGCACCTTGGGCT |

| TaqMhuGATA1F | CCTCATCCGGCCCAAGA |

| TaqMhuGATA1R | TGGTCGTCTGGCAGTTGGT |

| ProbeGATA1hu | TGATTGTCAGTAAACGGGCAGGTAC |

| TaqMhuGAPDHF | CCTGTTCGACAGTCAGCCG |

| TaqMhuGAPDHR | CGACCAAATCCGTTGACTCC |

| ProbeGAPDHhu | AGCCACATCGCTCAGACACCATGG |

| TaqMHPRThuF | GGCAGTATAATCCAAAGATGGTCAA |

| TaqMHPRThuR | TCAAATCCAACAAAGTCTGGCTTATAT |

| ProbeHPRThu | CTTGCTGGTGAAAAGGACCCCACGA |

| TaqMB2MhF | GCGGCATCTTCAAACCTCC |

| TaqMB2MhR | TGACTTTGTCACAGCCCAAGATA |

| ProbeB2Mh | TGATGCTGCTTACATGTCTCGATCCCACTT |

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol Reagent and treated with RNase-Free DNase. Reverse transcription was carried out with 500 ng total RNA. Real-time PCR was performed using the ABI 7900 Real-time PCR system and TaqMan PCR mastermix (Life Technologies). Quantification of gene amplification was performed in duplicate using the ΔΔCt method. The expression level of each gene was normalized using 3 housekeeping genes: hypoxantine-guanine-phosphoribosyl-transferase (HPRT) gene, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene, and β2 microglobulin gene. Primers and probes are listed.

Western blot analysis

Fifty thousand cells were harvested during the time course of erythroid cultures. Samples were run on a tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane glycine 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis resolving gel. Membranes were stained with following antibodies: GATA1 N-terminal (ab173816 rabbitAb; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and GATA1 C-Terminal (sc-1233; Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX), HSP70 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (#ADI SPA 812, #ADI SPA 810; Enzo Life Sciences, Villeurban, France), HSP90 (#4877; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), HSP27 (#2402; Cell Signaling), p53 (#5816; Sigma), phospho-p53 (ser15) (Cell Signaling), caspase-3 and its cleaved form, Bcl-Xl, PARP and its cleaved form (all rabbit polyclonal antibodies from Cell Signaling), β-actin (Ac-15) (Sigma-Aldrich), RPS19 (#57643; Abcam), RPL5 (#74744; Abcam), and the polyclonal antibody against RPL11 (gift from M. F. O’Donohue, Laboratoire de Biologie Moléculaire Eucaryote, Toulouse, France).

Confocal microscopy and imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream)

Confocal microscopy.

The cells were fixed at room temperature in 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized in 0.2% Triton-X. The staining was performed at 4°C overnight using antibody against HSP70 (ADI SPA 810 mouse mAb; Enzo Life Technologies) and GATA1 N-terminal (ab173816 rabbit pAb; Abcam). The secondary antibody staining was performed at room temperature for 1 hour using Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-mouse and Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-rabbit, respectively. Slides mounted in a Fluoromount-G slide mounting imaging medium (Sigma-Aldrich) were imaged using a Leica SPE confocal microscope at ×63 magnification. Acquired images were analyzed using Image J, Java Image processing program (NIH Image).

ImageStream.

The cells (1-2 × 106) were fixed and permeabilized using Foxp3 staining Buffer Set according to the manufacturer’s instructions (00-5523-00; Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Staining was performed using primary antibodies against HSP70, GATA1 N-terminal, hemoglobin (Hbb, Santa Cruz sc-21757), and DAPI, and secondary antibodies as used were as for confocal microscopy. Image acquisition at a ×60 magnification was performed using the ImageStream system and analyzed on an Imagestream ISX mkII (Amnis Corp. Millipore). Between 30 000 and 50 000 events were collected in all experiments. Single stain controls were run for each fluorochrome used, and spectral compensation was performed in IDEAS software (version 6.2, Amnis Corp. Millipore). Specific masks were designed for the analysis of the nuclear or the cytoplasmic localization of HSP70, GATA-1, and β-globin.

Proteasome inhibition

The proteasome of human primary cells or UT7-EPO cell lines was inhibited using 2 proteasome inhibitors: lactacystin and MG132 (both from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Cells were incubated in the culture medium with lactacystin at 50 µM for 2 hours or MG132 at 10 µM for 1 to 2 hours for human primary cells or for 5 hours for EPO-UT-7 cells.

Protein synthesis

UT-7 cells were washed with warm phosphate-buffered saline and incubated with methionine-free RPMI medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM l-glutamine for 1 hour at 37°C to deplete methionine. For metabolic labeling of protein, S35* radioactive isotope, 250 µCi of methionine cysteine S35 was added (pulse) for 6 hours. The cells were subsequently resuspended in complete medium containing methionine cysteine (chase). The protein extracts were processed by addition of a lysis buffer. Immunoprecipitation was performed using primary antibodies against HSP70 and actin. The proteins were separated using 10% bisacrylamide gel and then placed in a cassette with radioactive sensitive film. The newly synthesized proteins were detected after 5 days using the Curix 60 (AGFA).

Immunoprecipitation of HSP70

Protein extracts from 5 million EPO-UT-7 cells, untreated or treated with MG132, were collected from the lysis buffer. Whole cell lysates were used for immunoprecipitation using 5 μg of protein per sample of a goat polyclonal antibody against HSP70 bound beads or an anti-ubiquitin mAb-agarose (D058-8; MBL). The protein-protein interactions were identified by western blotting.

p53 induction

The primary human erythroid cells at day 7 were treated with 5, 10, or 20 µM of the p53 activator, nutlin 3A (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 to 4 hours. The resultant p53 activity was compared with that of cells cultured without nutlin 3A or with the inactive enantiomer molecule nutlin 3B.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPAd Prism (version 5.0; GraphPAd software) and IDEAS 6.2. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean of n determinations unless noted otherwise. Student t test or the Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare the data from different populations. Differences were considered significant at *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, and ****P < .0001.

Results

HSP70 protein expression is decreased during the early stages of erythroid differentiation in RPL5 and RPL11 haploinsufficient human primary erythroid cells

We generated erythroid cells by ex vivo differentiation of primary human CD34+ cells collected from healthy donors and RPL5+/Mut, RPL11+/Mut, and RPS19+/Mut DBA patients. At day 10 of culture, we observed that HSP70 protein expression was dramatically decreased in RPL5+/Mut and RPL11+/Mut as compared with healthy and RPS19+/Mut erythroid cells (Figure 1A). The decreased HSP70 expression level was also noted in a DBA-affected patient carrying a mutation in another ribosomal protein (RP) gene, RPS26 gene (supplemental Figure 1A). The decreased HSP70 expression was associated with a decrease in procaspase-3 expression (Figure 1A).

HSP70 expression level in human erythroid cell culture from DBA patients’ peripheral blood CD34+cells and from cord blood CD34+depleted in RPS19, RPL5, or RPL11 after shRNA infection. (A) Immunoblots of HSP70 and procaspase-3 at day 10 of erythroid cell culture (20 000 cells) from CD34+ peripheral blood from DBA-affected patients carrying various RP gene mutations: RPL5Mut/+ (UPN#412), RPL11Mut/+ (UPN#587), and RPS19Mut/+ (UPN#987, UPN#251, UPN#35) DBA-affected patients compared with the healthy controls (Co). HSP70 and procaspase-3 expression levels have been compared with β-actin expression. Molecular weight (Mr). (B) Immunoblots of HSP70 and procaspase-3 at day 7 of erythroid cell culture (50 000 cells) from cord blood CD34+ infected with various shRNAs against RPS19 (shRPS19), RPL5 (shRPL5-1 and shRPL5-2), and RPL11 (shRPL11) compared with noninfected CD34+ (Co) and Scramble (SCR). Representative of 5 independent experiments. Quantification of HSP70 protein immunoblot band intensity by ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health [NIH]) compared with β-actin from the 5 independent experiments is represented lower. (C) Study of HSP70 and GATA1 expression by immunostaining and analyzed by confocal microscopy at day 10 of erythroid cell culture from cord blood CD34+ infected with various shRNAs against RPS19 (shRPS19), RPL5 (shRPL5), and RPL11 (shRPL11) compared with noninfected CD34+ (Co). Shown are HSP70, GATA1, DAPI, and merged HSP70 and GATA1 stainings. Original magnification ×60. Scale bar represents 10 μm. (D) Study of HSP70 expression normalized to β-actin at day 6 of synchronized BFU-E and CFU-E progenitors obtained from cord blood CD34+ infected with various shRNAs against RPS19 (shRPS19), RPL5 (shRPL5), and RPL11 (shRPL11) compared with noninfected CD34+ (Co) and Scramble (SCR). Left: HSP70 expression after quantification of each immunoblot band by ImageJ software (NIH) compared with β-actin, in control BFU-E compared with shRPS19 and shRPL11 BFU-E (1 experiment-immunoblot in supplemental Figure 2E). Right top: HSP70 expression level after quantification of each immunoblot band by ImageJ software (NIH) compared with β-actin obtained in synchronized BFU-E and CFU-E. Right bottom: Immunoblot of HSP70 expression level in the synchronized BFU-E and CFU-E erythroid progenitors in each condition (20 000 cells/lane).

HSP70 expression level in human erythroid cell culture from DBA patients’ peripheral blood CD34+cells and from cord blood CD34+depleted in RPS19, RPL5, or RPL11 after shRNA infection. (A) Immunoblots of HSP70 and procaspase-3 at day 10 of erythroid cell culture (20 000 cells) from CD34+ peripheral blood from DBA-affected patients carrying various RP gene mutations: RPL5Mut/+ (UPN#412), RPL11Mut/+ (UPN#587), and RPS19Mut/+ (UPN#987, UPN#251, UPN#35) DBA-affected patients compared with the healthy controls (Co). HSP70 and procaspase-3 expression levels have been compared with β-actin expression. Molecular weight (Mr). (B) Immunoblots of HSP70 and procaspase-3 at day 7 of erythroid cell culture (50 000 cells) from cord blood CD34+ infected with various shRNAs against RPS19 (shRPS19), RPL5 (shRPL5-1 and shRPL5-2), and RPL11 (shRPL11) compared with noninfected CD34+ (Co) and Scramble (SCR). Representative of 5 independent experiments. Quantification of HSP70 protein immunoblot band intensity by ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health [NIH]) compared with β-actin from the 5 independent experiments is represented lower. (C) Study of HSP70 and GATA1 expression by immunostaining and analyzed by confocal microscopy at day 10 of erythroid cell culture from cord blood CD34+ infected with various shRNAs against RPS19 (shRPS19), RPL5 (shRPL5), and RPL11 (shRPL11) compared with noninfected CD34+ (Co). Shown are HSP70, GATA1, DAPI, and merged HSP70 and GATA1 stainings. Original magnification ×60. Scale bar represents 10 μm. (D) Study of HSP70 expression normalized to β-actin at day 6 of synchronized BFU-E and CFU-E progenitors obtained from cord blood CD34+ infected with various shRNAs against RPS19 (shRPS19), RPL5 (shRPL5), and RPL11 (shRPL11) compared with noninfected CD34+ (Co) and Scramble (SCR). Left: HSP70 expression after quantification of each immunoblot band by ImageJ software (NIH) compared with β-actin, in control BFU-E compared with shRPS19 and shRPL11 BFU-E (1 experiment-immunoblot in supplemental Figure 2E). Right top: HSP70 expression level after quantification of each immunoblot band by ImageJ software (NIH) compared with β-actin obtained in synchronized BFU-E and CFU-E. Right bottom: Immunoblot of HSP70 expression level in the synchronized BFU-E and CFU-E erythroid progenitors in each condition (20 000 cells/lane).

To further confirm that the normal expression of HSP70 was specific for RPS19-mutated DBA patients, we analyzed cells from 4 additional RPS19-mutated patients carrying various mutations in RPS19 gene during erythroid differentiation (supplemental Figure 1B). Cells from patient UPN#987 with mutant RPS19 gene could be cultured for the entire time course of erythroid differentiation, and HSP70 expression level was normal at all stages of erythroid differentiation. Patients UPN#35 and UPN#1039 were studied using 2 different erythroid culture protocols, and normal expression of HSP70 was noted under all conditions (supplemental Figure 1B).

These findings using primary cells from DBA patients could be reproduced by using shRNAs37 to specifically decrease the expression of RPL5, RPL11, and RPS19 genes in cord blood CD34+ cells prior to inducing their erythroid differentiation (Figure 1B). Efficiency of each shRNAs in knocking down RPL5, RPL11, and RPS19 mRNA was validated in each experiment (supplemental Figure 2A). In accordance with our previous observations, a downregulation of each of these 3 RP genes induced an increase in the phosphorylation of p53 (data not shown), whereas only the downregulation of RPL5 and RPL11 resulted in increased apoptosis, as suggested by a decrease in procaspase-3 expression and increased levels of cleaved caspase-3 (Figure 1B). The decreased HSP70 expression level in RPL5 and RPL11 haploinsufficient erythroid cells was confirmed by confocal microscopy (Figure 1C).

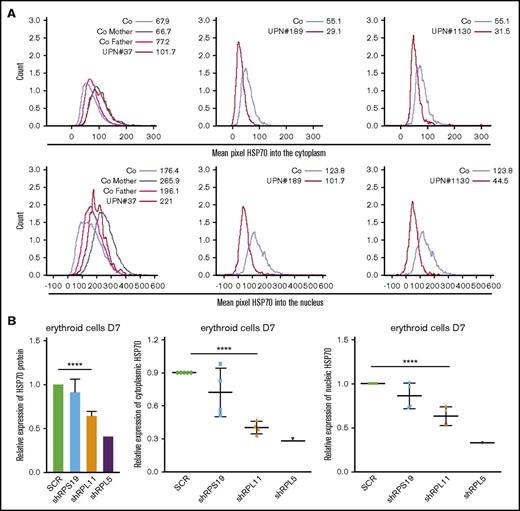

The downregulation of HSP70 protein in human RPL5 and RPL11 haploinsufficient erythroid cells was further confirmed in cells from DBA patients (Figure 2A) and in the shRNA model (Figure 2B) using imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream). Again, HSP70 expression level was significantly decreased in haploinsufficient RPL5 or RPL11 erythroid cells.

HSP70 expression level and subcellular localization measured by imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream) in human erythroid cells from various DBA patients and after RPS19 or RPL11 or RPL5 depletion of primitive CD34+cord blood cells. (A) HSP70 expression level measured by imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream) into the cytoplasm (top panels) and nucleus (bottom panels) in erythroid cells from DBA-affected patients (RPS19+/Mut UPN#37, RPL11+/Mut UPN#189 and UPN#1130 patients) and relatives (Co mother and father) at day 7 of culture compare with healthy controls (Co). Results are presented as the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). (B) HSP70 expression analysis compared with actin in the shRNA model using imaging flow cytometry in the total erythroid cells and in the cytoplasm and nucleus of these cells (ImageStream). The data are shown as the mean ± the standard deviation of 4 independent experiments. RPL5 shown as another non RPS19 gene. ****P < .0001.

HSP70 expression level and subcellular localization measured by imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream) in human erythroid cells from various DBA patients and after RPS19 or RPL11 or RPL5 depletion of primitive CD34+cord blood cells. (A) HSP70 expression level measured by imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream) into the cytoplasm (top panels) and nucleus (bottom panels) in erythroid cells from DBA-affected patients (RPS19+/Mut UPN#37, RPL11+/Mut UPN#189 and UPN#1130 patients) and relatives (Co mother and father) at day 7 of culture compare with healthy controls (Co). Results are presented as the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). (B) HSP70 expression analysis compared with actin in the shRNA model using imaging flow cytometry in the total erythroid cells and in the cytoplasm and nucleus of these cells (ImageStream). The data are shown as the mean ± the standard deviation of 4 independent experiments. RPL5 shown as another non RPS19 gene. ****P < .0001.

This decrease in HSP70 found in erythroid cells was not present in lymphoblastoid cell lines established from RPL5+/Mut and from RPL11+/Mut DBA patients, supporting our hypothesis for a cell-specific role for HSP70 in the erythroid tropism of the disease (supplemental Figure 2B). Furthermore, we did not detect any change in the basal expression levels of 2 other heat shock proteins, namely HSP90 and HSP27, in erythroid cells derived from shRNA-RPL5 (not shown), -RPL11, and -RPS19 lentiviral infected CD34+ cells, indicating a specific alteration of HSP70 (supplemental Figure 2C).

By sorting for human erythroid cells at defined stages of development (supplemental Figure 2D), we noted that HSP70 expression increased between normal BFU-E and CFU-E differentiation stages, (Figure 1D, right panel; supplemental Figure 2E), which was previously described for GATA1 expression.39 This differentiation-associated increase in HSP70 and GATA1 expression was conserved following shRNA-mediated downregulation of RPS19. In marked contrast, the expression of HSP70 was decreased at the BFU-e stage and remained decreased from BFU-E to CFU-E in cultures of both shRPL5- or shRPL11-transduced cord blood CD34+ cells (Figure 1D, right and left panels; supplemental Figure 2E). Moreover, HSP70 expression was clearly decreased in RPL5- and RPL11-deficient CFU-E compared with that of normal CFU-E (Figure 1D).

Decreased expression of HSP70 is not due to a mislocalization of the protein in DBA

Because mislocalization of subcellular HSP70 has been previously reported in MDS35 and in β-thalassemia erythroid cells,36 we analyzed the location of HSP70 during erythroid cell differentiation with confocal microscopy (Figure 1C) at day 10 or imaging flow cytometry (Figure 2A-B) at day 7 in several DBA patients (Figure 2A) and in shRNA-RPL5 and -RPL11 depleted erythroid cells (Figure 2B, lower panels). In 4 independent experiments, we observed a uniform decrease in HSP70 expression in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus of RPL5 and RPL11 haploinsufficient erythroid cells. We were unable to document abnormal redistribution of HSP70 between the 2 cell compartments. We made a similar observation in a mother and her son, both affected with DBA and carrying the same RPL11 gene mutation (UPN#189 and UPN#1130) (Figure 2A). In contrast, we did not find a decreased HSP70 expression in the proband (UPN#37) of a DBA family member carrying a RPS19 gene mutation (Figure 2A).

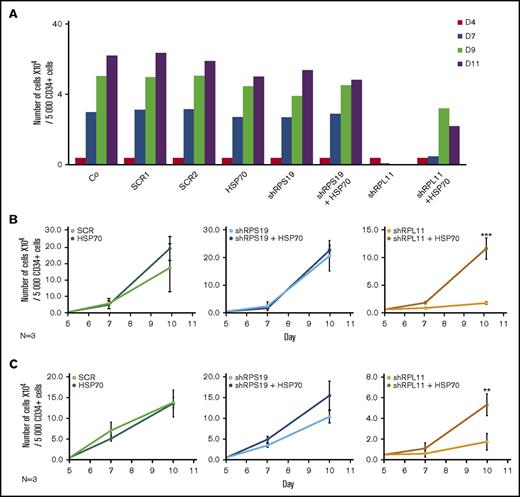

HSP70 overexpression rescues erythroid proliferation defect in RPL11-deficient cells

Transduction of wild-type HSP70 cDNA into RPL11-haploinsufficient CD34+ cells partially rescued the proliferation defect of erythroid cells from day 7 to day 11 in the culture system, whereas HSP70 overexpression did not significantly modify the erythroid differentiation of RPS19 haploinsufficient cells (Figure 3A). We subsequently synchronized erythroid cell cultures before sorting for BFU-E (Figure 3B) and CFU-E (Figure 3C) progenitors to induce their erythroid differentiation and confirmed the major defect in proliferation of RPL11-deficient cells compared with RPS19-deficient and control erythroid cells. Overexpression of HSP70 in RPL11-deficient CD34+ cells significantly increased the proliferation of BFU-E (Figure 3B) and CFU-E- (Figure 3C) derived erythroid cells. In contrast, over expression of HSP70 in RPS19-haploinsufficient CD34+ cells had little or no effect on erythroid proliferation (Figures 3B-C). Taken together these findings establish that HSP70-mediated effects on erythroid progenitors are the cause of erythroid proliferative defect in RPL5 and RPL11 deficient cells.

Overexpression of wild-type (WT) HSP70 restored HSP70, GATA1, and erythroid proliferation in depleted RPL11 erythroid progenitors. (A) Erythroid proliferation (number of cells ×104) during the time course from day 4 to day 11 of erythroid culture from normal cord blood CD34+ depleted in RPS19 or RPL11 by specific shRNAs has been studied compared with noninfected CD34+ cells (Co) or infected with various random scrambles (SCR-1 and SCR-2) or WT HSP70 cDNA lentivirus. The depleted RPS19 or RPL11 erythroid cell proliferation has been studied with and without WT HSP70 cDNA lentivirus infection. Five thousand CD34+ cells have been plated at day 4. Erythroid proliferation has been calculated compared with this number during the time course. Study of erythroid proliferation (number of cells ×104) between day 5 and day 10 from synchronized BFU-E (B) and CFU-E (C) erythroid progenitors in RPS19 or RPL11 deficient erythroid cells compared with SCR infected cells or WT HSP70 cDNA lentivirus infection (left panels). The depleted RPS19 (middle panels) or RPL11 (right panels) erythroid cell proliferation has been studied with (black spots) and without (white spots) WT HSP70 cDNA lentivirus infection. Five thousand CD34+ cells have been plated at day 5. Erythroid proliferation has been calculated compared with this number during the time course at days 7 and 10. Counting of the erythroid cells has been performed using flow cytometry (shown) and manual count under the microscope in triplicate. The data are shown as the mean ± the standard deviation (n = 3 experiments). **P < .01; ***P < .001. Expression level of total HSP70 and its cytoplasmic and nuclear subcellular distribution (D) and nuclear expression of GATA1 (E) in deficient RPS19 (shRPS19) and RPL11 (shRPL11) erythroid cells after (dark blue and red curves, respectively) or not (light blue and orange curves, respectively) WT HSP70 cDNA lentivirus infection at day 10 of synchronized erythroid culture. The results are presented in MFI obtained by using imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream). The vertical green and red lines represented the MFI of HSP70 expression (D) and GATA1 (E) in erythroid cells infected with shSCR or WT HSP70 cDNA lentivirus in depleted RPL11 cells, respectively. The total efficiency of the HSP70 rescue is shown by the overlapping of both lines as shown on the total expression of HSP70 but also in nucleic GATA1 expression. (F) Imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream) analysis of GATA1 and HSP70 immunostainings in synchronized erythroid cells at day 7 of culture after depletion of RPS19-shRNA or RPL11-shRNA and overexpression or not of WT HSP70 cDNA. Shown are HSP70, GATA1, DAPI, and merged HSP70 and GATA1 stainings. Original magnification ×60. Scale bar represents 10 µm. (G) β-globin expression level in deficient RPL11 (shRPL11) erythroid cells after (red curve) or not (orange curve) WT HSP70 cDNA lentivirus rescue at day 10 of synchronized erythroid culture. The results are presented as the MFI obtained by using imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream).

Overexpression of wild-type (WT) HSP70 restored HSP70, GATA1, and erythroid proliferation in depleted RPL11 erythroid progenitors. (A) Erythroid proliferation (number of cells ×104) during the time course from day 4 to day 11 of erythroid culture from normal cord blood CD34+ depleted in RPS19 or RPL11 by specific shRNAs has been studied compared with noninfected CD34+ cells (Co) or infected with various random scrambles (SCR-1 and SCR-2) or WT HSP70 cDNA lentivirus. The depleted RPS19 or RPL11 erythroid cell proliferation has been studied with and without WT HSP70 cDNA lentivirus infection. Five thousand CD34+ cells have been plated at day 4. Erythroid proliferation has been calculated compared with this number during the time course. Study of erythroid proliferation (number of cells ×104) between day 5 and day 10 from synchronized BFU-E (B) and CFU-E (C) erythroid progenitors in RPS19 or RPL11 deficient erythroid cells compared with SCR infected cells or WT HSP70 cDNA lentivirus infection (left panels). The depleted RPS19 (middle panels) or RPL11 (right panels) erythroid cell proliferation has been studied with (black spots) and without (white spots) WT HSP70 cDNA lentivirus infection. Five thousand CD34+ cells have been plated at day 5. Erythroid proliferation has been calculated compared with this number during the time course at days 7 and 10. Counting of the erythroid cells has been performed using flow cytometry (shown) and manual count under the microscope in triplicate. The data are shown as the mean ± the standard deviation (n = 3 experiments). **P < .01; ***P < .001. Expression level of total HSP70 and its cytoplasmic and nuclear subcellular distribution (D) and nuclear expression of GATA1 (E) in deficient RPS19 (shRPS19) and RPL11 (shRPL11) erythroid cells after (dark blue and red curves, respectively) or not (light blue and orange curves, respectively) WT HSP70 cDNA lentivirus infection at day 10 of synchronized erythroid culture. The results are presented in MFI obtained by using imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream). The vertical green and red lines represented the MFI of HSP70 expression (D) and GATA1 (E) in erythroid cells infected with shSCR or WT HSP70 cDNA lentivirus in depleted RPL11 cells, respectively. The total efficiency of the HSP70 rescue is shown by the overlapping of both lines as shown on the total expression of HSP70 but also in nucleic GATA1 expression. (F) Imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream) analysis of GATA1 and HSP70 immunostainings in synchronized erythroid cells at day 7 of culture after depletion of RPS19-shRNA or RPL11-shRNA and overexpression or not of WT HSP70 cDNA. Shown are HSP70, GATA1, DAPI, and merged HSP70 and GATA1 stainings. Original magnification ×60. Scale bar represents 10 µm. (G) β-globin expression level in deficient RPL11 (shRPL11) erythroid cells after (red curve) or not (orange curve) WT HSP70 cDNA lentivirus rescue at day 10 of synchronized erythroid culture. The results are presented as the MFI obtained by using imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream).

Using imaging flow cytometry, we noted that the HSP70 expressed in RPL11-haploinsufficient cells following transfection with HSP70 cDNA localized in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm of erythroid cells (Figure 3D). Importantly, overexpression of HSP70 in RPL11-haploinsufficient erythroid cells induced a significant increase in GATA1 expression level in the cell nucleus (Figure 3E-F; supplemental Figure 3). Finally, in RPL11-haploinsufficient cells, overexpression of HSP70 increased the expression of total β-globin chains, the major erythroid cell protein whose gene expression is controlled by GATA1, an effect observed as soon as globin chain synthesis is initiated at day 7 (Figure 3G).

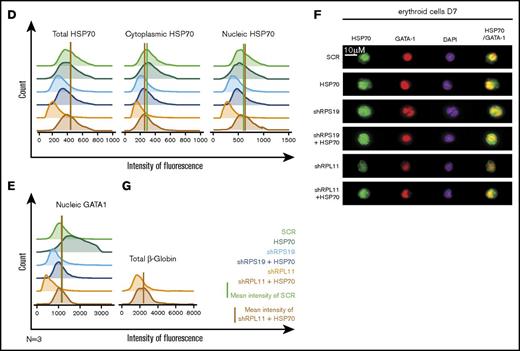

HSP70 overexpression rescues erythroid progenitor proliferation, restores erythroid terminal differentiation, decreases apoptosis, and improves globin expression in DBA patients

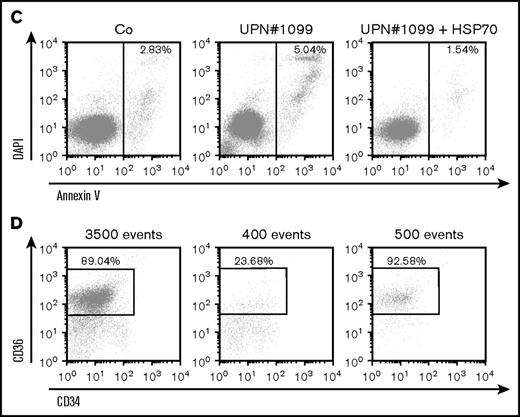

Transduction of wild-type HSP70 gene into peripheral blood CD34+ cells collected from 5 DBA patients increased cell proliferation in our erythroid cell culture system (Figure 4A). Interestingly, a mother (UPN#189) and her son (UPN#1130) carrying the same RPL11 gene mutation exhibited a very similar decrease in erythroid proliferation at the steady state and both showed a similar increase in proliferation following overexpression of HSP70 (Figure 4A, lowest right panel). At day 9 of synchronized erythroid cell culture, HSP70 expression level was similar in RPL11+/Mut HSP70 transduced cells to that observed in controls (Figure 4B; supplemental Figure 4), which was associated with an increase in both GATA1 protein level (Figure 4B; supplemental Figure 4) and α and β globin chain expression (Figure 4B, top and bottom panels; supplemental Figure 4). HSP70 overexpression in RPL11+/Mut DBA patient cells also decreased the level of apoptosis of erythroid cells in culture, which resulted in an increase in caspase-3 expression level (Figure 4B; supplemental Figure 4). A similar decrease in annexin V labeling was also noted following HSP70 overexpression in another RPL11+/Mut DBA patient erythroid cells (Figure 4C). Finally, HSP70 overexpression increased the fraction of CD34−/CD36+ erythroid cells (Figure 4D).

HSP70 overexpression rescued erythroid proliferation and differentiation and decreased the apoptosis of erythroid cells in mutated RPL11+/MutDBA patients. (A) Study of erythroid proliferation (number of cells ×104) between day 6 and days 14 or 15 from CD34+ peripheral blood from various DBA-affected patients carrying a mutation in RPS19 gene (UPN#37) (middle and bottom left plots) or RPL11 gene (UPN#172 (top and middle right plots), UPN#189 (red dot), and UPN#1130 (yellow dot) (bottom right plot) compared with healthy controls (Co) (open circle) or CD34+ cells infected with WT HSP70 cDNA lentivirus (filled circle) (top left plot). Erythroid cells from DBA affected patients have been analyzed with or without WT HSP70 cDNA lentivirus infection. Counting of the erythroid cells has been performed using flow cytometry (shown) and manual count under the microscope in triplicate. Five thousand CD34+ cells have been plated at day 0. Erythroid proliferation has been calculated compared with this number of cells during the time course at days 9, 12, and 14 or 15. (B) Top panel: western blot is shown from the erythroid cells (20 000 cells) obtained at day 10 from CD34+ peripheral blood from a DBA affected patient carrying a mutation in RPL11 gene (UPN#479). CD34+ DBA patients’ cells in erythroid differentiation have been studied without or with wild-type HSP70 cDNA lentivirus infection. HSP70, GATA1, procaspase-3 and β-globin protein expressions have been studied compared with β-actin expression level. Bottom panel: a RPL11+/Mut DBA affected patient exhibited a defect in α-globin and β-globin expression level in accordance with the hemoglobin concentration of the patient. Overexpression of wild-type cDNA HSP70 in erythroid cells from the RPL11+/Mut UPN#172 DBA affected patient restored α-globin and β-globin expression in this patient compared with the normal erythroid cells transduced with wild-type cDNA HSP70. Globin gene expression level has been measured by imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream). (C-D) Representative FACS histogram plots of cultured erythroid cells (10 000 cells) from a healthy control (Co) (left panels), a RPL11+/Mut DBA patient (UPN#1099) (middle panels), and this patient after wild-type HSP70 cDNA lentivirus infection. (C) Apoptosis analysis on the DAPI and annexin V labeling. DAPI−/annexin V+ apoptotic erythroid cells have been quantified in percentage. (D) Erythroid differentiation analysis on the CD34/CD36 labeling. In all the FACS histogram plots, the ordinate and the abscissa measured the number of cells displaying the fluorescent intensity of the different antibody staining.

HSP70 overexpression rescued erythroid proliferation and differentiation and decreased the apoptosis of erythroid cells in mutated RPL11+/MutDBA patients. (A) Study of erythroid proliferation (number of cells ×104) between day 6 and days 14 or 15 from CD34+ peripheral blood from various DBA-affected patients carrying a mutation in RPS19 gene (UPN#37) (middle and bottom left plots) or RPL11 gene (UPN#172 (top and middle right plots), UPN#189 (red dot), and UPN#1130 (yellow dot) (bottom right plot) compared with healthy controls (Co) (open circle) or CD34+ cells infected with WT HSP70 cDNA lentivirus (filled circle) (top left plot). Erythroid cells from DBA affected patients have been analyzed with or without WT HSP70 cDNA lentivirus infection. Counting of the erythroid cells has been performed using flow cytometry (shown) and manual count under the microscope in triplicate. Five thousand CD34+ cells have been plated at day 0. Erythroid proliferation has been calculated compared with this number of cells during the time course at days 9, 12, and 14 or 15. (B) Top panel: western blot is shown from the erythroid cells (20 000 cells) obtained at day 10 from CD34+ peripheral blood from a DBA affected patient carrying a mutation in RPL11 gene (UPN#479). CD34+ DBA patients’ cells in erythroid differentiation have been studied without or with wild-type HSP70 cDNA lentivirus infection. HSP70, GATA1, procaspase-3 and β-globin protein expressions have been studied compared with β-actin expression level. Bottom panel: a RPL11+/Mut DBA affected patient exhibited a defect in α-globin and β-globin expression level in accordance with the hemoglobin concentration of the patient. Overexpression of wild-type cDNA HSP70 in erythroid cells from the RPL11+/Mut UPN#172 DBA affected patient restored α-globin and β-globin expression in this patient compared with the normal erythroid cells transduced with wild-type cDNA HSP70. Globin gene expression level has been measured by imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream). (C-D) Representative FACS histogram plots of cultured erythroid cells (10 000 cells) from a healthy control (Co) (left panels), a RPL11+/Mut DBA patient (UPN#1099) (middle panels), and this patient after wild-type HSP70 cDNA lentivirus infection. (C) Apoptosis analysis on the DAPI and annexin V labeling. DAPI−/annexin V+ apoptotic erythroid cells have been quantified in percentage. (D) Erythroid differentiation analysis on the CD34/CD36 labeling. In all the FACS histogram plots, the ordinate and the abscissa measured the number of cells displaying the fluorescent intensity of the different antibody staining.

Altogether, HSP70 overexpression prevented erythroid cell death and restored erythroid cell differentiation of RPL11+/Mut DBA patient CD34+ cells in culture.

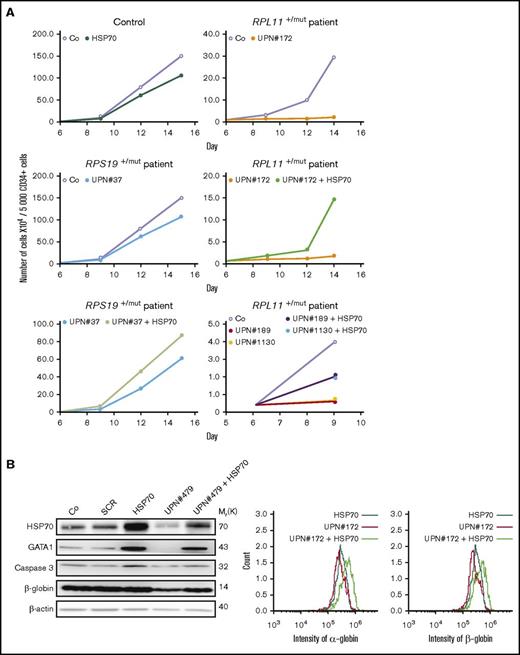

HSP70 is degraded by the proteasome during erythroid differentiation in RPL5- and RPL11-depleted erythroid cells

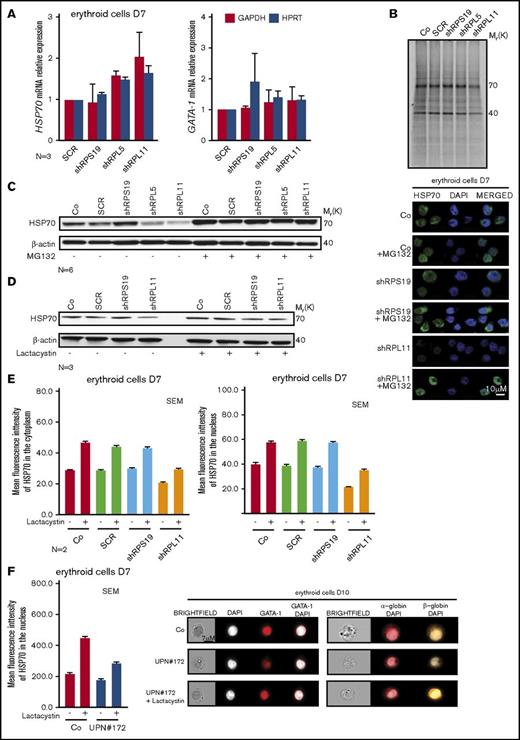

We subsequently explored the mechanism leading to the decreased expression of HSP70 observed in erythroid cells of RPL5- and RPL11-haploinsufficient DBA patients. This decrease is not at the transcriptional level as we did not detect any significant differences in HSP70 mRNA expression in RP-haploinsufficient erythroid cells compared with control cells and 2 different reporter genes (Figure 5A). GATA1 mRNA expression was also similar to that of control cells as previously documented.31 We also used metabolic S35 tracing to measure the synthesis of HSP70 in RPL5- and RPL11-haploinsufficient compared with wild-type and RPS19-haploinsufficient cells. This experiment, performed in EPO-dependent UT-7 cells, did not reveal any impact of RP haploinsufficiency on HSP70 synthesis (Figure 5B).

HSP70 decreased expression level is because of a proteasomal degradation. (A) HSP70 and GATA1 gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR in CD34+ human cells, transduced with shRPS19, shRPL5, or shRPL11 relative to the Scramble (SCR) transduced cells and compared with nontransduced cells (Co) at day 7 of erythroid differentiation. The data are shown as the mean ± the standard deviation (for 3 independent samples) and normalized to GAPDH and HPRT reporter genes. (B) Immunoprecipitation of HSP70 protein after S35* metabolic staining of EPO-dependent UT-7 cell line depleted in RPS19 (shRPS19), in RPL5 (shRPL5), or in RPL11 (shRPL11) compared with SCR transduced erythroid cells or nontransduced cells (Co). HSP70 is normally expressed at 70 kDa in each condition. Western blot of HSP70 protein is shown in depleted RPS19 (shRPS19), or RPL11 (shRPL11) erythroid cells compared with controls (Co and SCR), at day 7 after proteasome inhibitor treatment. The cells have been treated with or without MG132 at 10 µM for 1 hour (C) or with or without lactacystin at 50 µM for 2 hours (D). (E) Left panels: Analysis of HSP70 protein expression level in the 2 subcellular compartments (cytoplasm, left panel and nucleus, right panel) of erythroid cells at day 7 of terminal erythroid differentiation in depleted RPS19 (shRPS19), and RPL11 (shRPL11) erythroid cells compared with controls (Co, SCR). The erythroid cells have been treated with or without lactacystin at 50 µM for 2 hours. The results obtained by using imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream) are presented as the MFI ± the standard deviation representative of 3 independent experiments. Right panel: HSP70 protein expression and localization analysis by confocal microscopy in erythroid cells transduced with shRPS19 or shRPL11 compared with nontransduced cells (Co) at day 7 of erythroid culture. The erythroid cells have been treated with or without MG132 at 10 µM for 1 hour. Shown are HSP70, DAPI, and merged HSP70 and DAPI stainings. Original magnification ×60. Scale bar represents 10 µm. (F) HSP70 protein expression into the nucleus of erythroid cells at day 7 of erythroid culture from a DBA-affected patient (UPN#172), carrying a mutation in RPL11 gene (left panel). The erythroid cells have been treated with or without lactacystin at 50 µM for 2 hours. The results obtained by using imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream) are presented as the MFI ± the standard deviation. Representative images obtained using imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream) of GATA1 (middle panel), α-globin and β-globin (right panel) in erythroid cells at day 10 of culture from the RPL11+/Mut mutated DBA-affected patient (UPN#172) compared with a healthy control (Co). The erythroid cells from the DBA patient have been treated with or without lactacystin at 50 µM for 2 hours. Shown standard bright-field images, DAPI, GATA1 and merged GATA1/DAPI, α-globin/DAPI, and β-globin/DAPI stainings. Original magnification ×60. Scale bar represents 7 µm.

HSP70 decreased expression level is because of a proteasomal degradation. (A) HSP70 and GATA1 gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR in CD34+ human cells, transduced with shRPS19, shRPL5, or shRPL11 relative to the Scramble (SCR) transduced cells and compared with nontransduced cells (Co) at day 7 of erythroid differentiation. The data are shown as the mean ± the standard deviation (for 3 independent samples) and normalized to GAPDH and HPRT reporter genes. (B) Immunoprecipitation of HSP70 protein after S35* metabolic staining of EPO-dependent UT-7 cell line depleted in RPS19 (shRPS19), in RPL5 (shRPL5), or in RPL11 (shRPL11) compared with SCR transduced erythroid cells or nontransduced cells (Co). HSP70 is normally expressed at 70 kDa in each condition. Western blot of HSP70 protein is shown in depleted RPS19 (shRPS19), or RPL11 (shRPL11) erythroid cells compared with controls (Co and SCR), at day 7 after proteasome inhibitor treatment. The cells have been treated with or without MG132 at 10 µM for 1 hour (C) or with or without lactacystin at 50 µM for 2 hours (D). (E) Left panels: Analysis of HSP70 protein expression level in the 2 subcellular compartments (cytoplasm, left panel and nucleus, right panel) of erythroid cells at day 7 of terminal erythroid differentiation in depleted RPS19 (shRPS19), and RPL11 (shRPL11) erythroid cells compared with controls (Co, SCR). The erythroid cells have been treated with or without lactacystin at 50 µM for 2 hours. The results obtained by using imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream) are presented as the MFI ± the standard deviation representative of 3 independent experiments. Right panel: HSP70 protein expression and localization analysis by confocal microscopy in erythroid cells transduced with shRPS19 or shRPL11 compared with nontransduced cells (Co) at day 7 of erythroid culture. The erythroid cells have been treated with or without MG132 at 10 µM for 1 hour. Shown are HSP70, DAPI, and merged HSP70 and DAPI stainings. Original magnification ×60. Scale bar represents 10 µm. (F) HSP70 protein expression into the nucleus of erythroid cells at day 7 of erythroid culture from a DBA-affected patient (UPN#172), carrying a mutation in RPL11 gene (left panel). The erythroid cells have been treated with or without lactacystin at 50 µM for 2 hours. The results obtained by using imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream) are presented as the MFI ± the standard deviation. Representative images obtained using imaging flow cytometry (ImageStream) of GATA1 (middle panel), α-globin and β-globin (right panel) in erythroid cells at day 10 of culture from the RPL11+/Mut mutated DBA-affected patient (UPN#172) compared with a healthy control (Co). The erythroid cells from the DBA patient have been treated with or without lactacystin at 50 µM for 2 hours. Shown standard bright-field images, DAPI, GATA1 and merged GATA1/DAPI, α-globin/DAPI, and β-globin/DAPI stainings. Original magnification ×60. Scale bar represents 7 µm.

Proteasome inhibition with either MG132 (Figure 5C) or lactacystin (Figure 5D) restored the expression of HSP70 to normal level in RPL5- or RPL11-deficient erythroid cells. Proteasome inhibitors also increased the expression of HSP70 in noninfected and SCR-infected erythroid cells, suggesting that the proteasomal machinery could regulate HSP70 expression level during normal erythroid differentiation (Figures 5C-D; supplemental Figure 5A). The expression of the other stress-inducible HSP27 and HSP90 remained unchanged in these cells treated with proteasome inhibitors (data not shown). Cell treatment with either MG132 or lactacystin restored HSP70 protein expression in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus of erythroid cells (Figure 5E) with MG132 appearing to be more effective. Importantly, lactacystin treatment resulted in increased HSP70 in erythroid cells derived from RPL11+/Mut DBA patient CD34+ cells from peripheral blood at day 7 (Figure 5F, left panel) with partial restoration of GATA1 expression in RPL11-haploinsufficient erythroid cells (Figure 5F, middle panel). Finally, in these cells, lactacystin also increased expression levels of α- and β-globin chains (Figure 5F, right panel). Because we did not observe any impact of RP gene haploinsufficiency on the overall proteasomal activity measured in CD34+ cells undergoing erythroid differentiation (supplemental Figure 5B), HSP70 proteasomal degradation is not the result of a global deregulation of protein degradation in these cells and the effect of proteasome inhibitors on HSP70 expression in RPL5- or RPL11-deficient erythroid cells appears to be specific to HSP70.

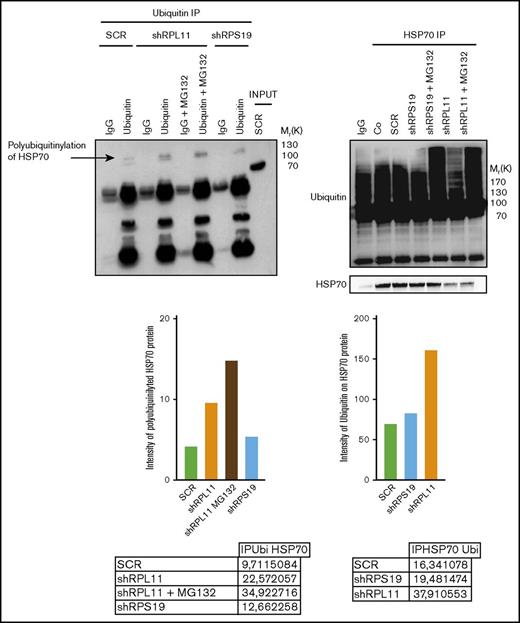

HSP70 is targeted for proteasomal degradation after ubiquitination

We subsequently explored if posttranslational polyubiquitination of the protein could control its degradation rate.40 Analysis of the human HSP70 protein sequence identified several lysine residues as potential targets for ubiquitination (supplemental Figure 6). Three putative ubiquitination sites, located at the lysine amino acid residues in position 524, 526, and 550, were reported by both databases with a high level of confidence. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments performed in control and RP-deficient EPO dependent UT-7 cells, that is, immunoprecipitation of mono and polyubiquitinated proteins followed by immunoblotting with an anti-HSP70 antibody (Figure 6, left panel) and immunoprecipitation of HSP70 followed by immunoblotting with an anti-ubiquitin antibody (Figure 6, right panel), identified increased polyubiquitination of HSP70 in RPL11- compared with RPS19-deficient cells. Treatment of cells with MG132 improved the detection of polyubiquitinated HSP70 in RPL11 and RPS19-depleted EPO dependent UT-7 cell lines (Figure 6).

HSP70 is ubiquitinated in RPL11 invalidated cells before proteasomal degradation. Left panel: Immunoprecipitation (IP) of ubiquitinated stained proteins (ubiquitin lanes) compared with the immunoprecipitation with an immunoglobulin G (IgG) control antibody (IgG lanes) in UT-7 cells cultured under EPO and infected with either the shRPS19 or the shRPL11, compared with the SCRamble (shSCR). Proteins after immunoprecipitation have been revealed with an antibody against HSP70. shRPL11 cells were treated or not with MG132 at 10 µM for 5 hours. HSP70 expression has been analyzed in the total cell lysate (INPUT) to validate that the HSP70 protein is present in all the studied samples. IgG lane: IgG control antibody; ubiquitin lane: anti-ubiquitin specific antibody in order to immunoprecipitate the ubiquitinated proteins; IgG+MG132 lane: IgG control antibody immunoprecipitation after cell treatment with the proteasome inhibitor, MG132; ubiquitin+MG132: anti-ubiquitin specific antibody for ubiquitinated proteins after cell treatment with the proteasome inhibitor, MG132. Right panel: Immunoprecipitation of HSP70 stained protein. The proteins have been then revealed by an antibody against ubiquitin (top of the western blot) and against HSP70 (bottom of the western blot) in UT-7 cells cultured under EPO and infected with either the shRPS19 or the shRPL11, compared with the SCRamble (shSCR) and noninfected cells (Co). These cells were also treated or not with MG132 at 10 µM for 5 hours. IgG lane: IgG control antibody; HSP70 IP lanes: HSP70 specific antibody in order to immunoprecipitate HSP70 proteins in depleted RPS19, RPL11 after or not MG132 cell treatment and compare with the SCRamble (shSCR) and noninfected cells (Co).

HSP70 is ubiquitinated in RPL11 invalidated cells before proteasomal degradation. Left panel: Immunoprecipitation (IP) of ubiquitinated stained proteins (ubiquitin lanes) compared with the immunoprecipitation with an immunoglobulin G (IgG) control antibody (IgG lanes) in UT-7 cells cultured under EPO and infected with either the shRPS19 or the shRPL11, compared with the SCRamble (shSCR). Proteins after immunoprecipitation have been revealed with an antibody against HSP70. shRPL11 cells were treated or not with MG132 at 10 µM for 5 hours. HSP70 expression has been analyzed in the total cell lysate (INPUT) to validate that the HSP70 protein is present in all the studied samples. IgG lane: IgG control antibody; ubiquitin lane: anti-ubiquitin specific antibody in order to immunoprecipitate the ubiquitinated proteins; IgG+MG132 lane: IgG control antibody immunoprecipitation after cell treatment with the proteasome inhibitor, MG132; ubiquitin+MG132: anti-ubiquitin specific antibody for ubiquitinated proteins after cell treatment with the proteasome inhibitor, MG132. Right panel: Immunoprecipitation of HSP70 stained protein. The proteins have been then revealed by an antibody against ubiquitin (top of the western blot) and against HSP70 (bottom of the western blot) in UT-7 cells cultured under EPO and infected with either the shRPS19 or the shRPL11, compared with the SCRamble (shSCR) and noninfected cells (Co). These cells were also treated or not with MG132 at 10 µM for 5 hours. IgG lane: IgG control antibody; HSP70 IP lanes: HSP70 specific antibody in order to immunoprecipitate HSP70 proteins in depleted RPS19, RPL11 after or not MG132 cell treatment and compare with the SCRamble (shSCR) and noninfected cells (Co).

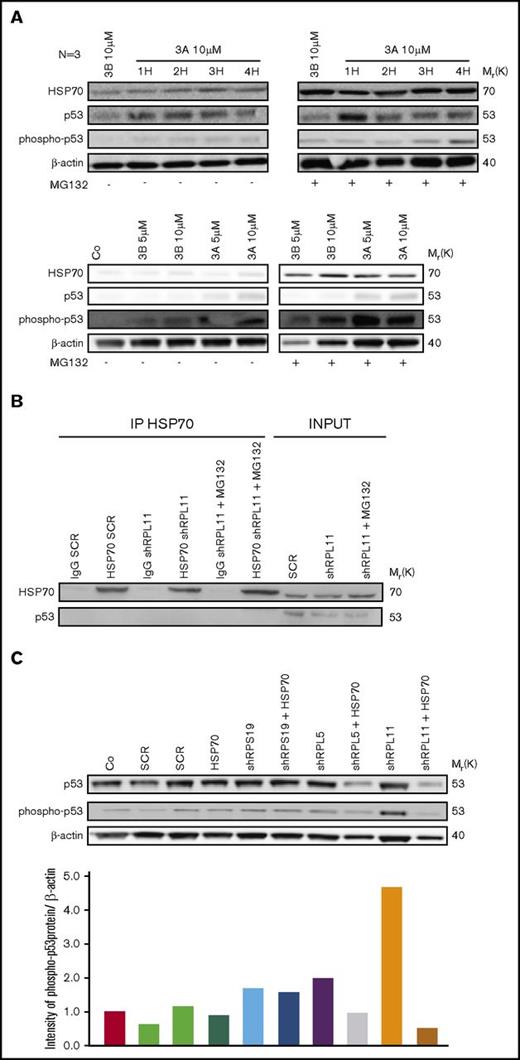

HSP70 proteasomal degradation is not due to p53 activation, but overexpression of HSP70 is able to reduce p53 stabilization

We have previously shown that the level of p53 activation in erythroid cells derived from DBA patients varies depending on the RP gene involved.37 We therefore wondered whether the HSP70 degradation was related to the level of p53 activation. To determine the link between HSP70 degradation and p53 stabilization, we used nutlin 3A, an activator of p53, at different concentrations or durations during culture. We also studied for comparison the effects of nutlin 3B, which has the opposite effect by inhibiting p53. In normal human erythroid cells, HSP70 was normally expressed and had increased expression with p53 activation by nutlin 3A. MG132 treatment increased HSP70 expression level in normal erythroid cells but the expression pattern was not affected by treatment with either nutlin 3A or nutlin 3B (Figure 7A). In UT-7 cells, with or without downregulation of RPL11, coimmunoprecipitation experiments did not detect any interaction between HSP70 and p53, even when RPL11-deficient UT-7 cells were treated with MG132 (Figure 7B). However, in haploinsufficient RPL11- or RPL5-deficient erythroid cells, overexpression of HSP70 led to decrease in p53 expression and phosphorylation (Figure 7C). These results indicate that HSP70 proteasomal degradation favors p53 accumulation and phosphorylation, which is not the case in RPS19-deficient erythroid cells. Decreased expression in HSP70, leading to the GATA-1 cleavage by caspase-3 during erythroid differentiation may be involved indirectly in the stabilization of p53 in the more severe DBA phenotypes. GATA-1 deficiency may be the factor responsible for p53 activation in DBA, as previously reported41 and may also explain the differences in p53 activation depending on the mutated RP gene involved in DBA patients, as we have previously described.37

HSP70 and p53 expression level analysis. (A) Study of HSP70, p53, phosphorylated (Ser15) p53 protein expression level compared with actin in normal erythroid cells from CD34+ primary cells at day 7 of the erythroid culture. Cells have been treated with nutlin 3A, a p53 activator, which increased p53 stabilization, for 1 hour (1H) to 4 hours (4H) compared with nutlin 3B, the inactive enantiomer. In addition, these erythroid cells have been treated with (right western blot) or not (left western blot) MG132 proteasome inhibitor at 10 µM for 1 hour. Different concentrations of nutlin 3A and 3B (5 to 10 µM) for 1 hour have been also tested with (right western blot) or not (left western blot) MG132 proteasome inhibitor at 10 µM for 1 hour (western blots below). (B) Immunoprecipitation of HSP70 revealed by an antibody against p53 and HSP70 as a control in depleted RPL11 (shRPL11) UT7-EPO dependent erythroid cells, compared with the control (shSCR) after or not a MG132 treatment. IgG SCR lane: IgG control antibody in shSCR infected cells; HSP70 SCR: immunoprecipitation with a specific antibody for HSP70 in shSCR infected cells; IgG shRPL11: IgG control antibody in RPL11 depleted cells; HSP70 shRPL11: immunoprecipitation with a specific antibody for HSP70 in RPL11 depleted cells; IgG shRPL11+MG132: IgG control antibody on shRPL11 depleted erythroid cells after treatment with MG132; HSP70 shRPL11+MG132: immunoprecipitation with a specific antibody for HSP70 in RPL11 depleted cells, treated with MG132. The expression level analysis of HSP70 and p53 has been performed in total cell lysate (INPUT lanes) in order to validate that the p53 and HSP70 were correctly expressed in the samples before immunoprecipitation. (C) Study of p53, phosphorylated (Ser15) p53 protein expression compare with actin in depleted RPS19, RPL5, or RPL11 erythroid cells from CD34+ primary cells at day 7 of erythroid culture after a rescue or not with the lentivirus containing the WT HSP70 cDNA. Quantification of P-p53 compared with β-actin (bottom panel) has been performed on Image J, Java Image processing program (NIH Image).

HSP70 and p53 expression level analysis. (A) Study of HSP70, p53, phosphorylated (Ser15) p53 protein expression level compared with actin in normal erythroid cells from CD34+ primary cells at day 7 of the erythroid culture. Cells have been treated with nutlin 3A, a p53 activator, which increased p53 stabilization, for 1 hour (1H) to 4 hours (4H) compared with nutlin 3B, the inactive enantiomer. In addition, these erythroid cells have been treated with (right western blot) or not (left western blot) MG132 proteasome inhibitor at 10 µM for 1 hour. Different concentrations of nutlin 3A and 3B (5 to 10 µM) for 1 hour have been also tested with (right western blot) or not (left western blot) MG132 proteasome inhibitor at 10 µM for 1 hour (western blots below). (B) Immunoprecipitation of HSP70 revealed by an antibody against p53 and HSP70 as a control in depleted RPL11 (shRPL11) UT7-EPO dependent erythroid cells, compared with the control (shSCR) after or not a MG132 treatment. IgG SCR lane: IgG control antibody in shSCR infected cells; HSP70 SCR: immunoprecipitation with a specific antibody for HSP70 in shSCR infected cells; IgG shRPL11: IgG control antibody in RPL11 depleted cells; HSP70 shRPL11: immunoprecipitation with a specific antibody for HSP70 in RPL11 depleted cells; IgG shRPL11+MG132: IgG control antibody on shRPL11 depleted erythroid cells after treatment with MG132; HSP70 shRPL11+MG132: immunoprecipitation with a specific antibody for HSP70 in RPL11 depleted cells, treated with MG132. The expression level analysis of HSP70 and p53 has been performed in total cell lysate (INPUT lanes) in order to validate that the p53 and HSP70 were correctly expressed in the samples before immunoprecipitation. (C) Study of p53, phosphorylated (Ser15) p53 protein expression compare with actin in depleted RPS19, RPL5, or RPL11 erythroid cells from CD34+ primary cells at day 7 of erythroid culture after a rescue or not with the lentivirus containing the WT HSP70 cDNA. Quantification of P-p53 compared with β-actin (bottom panel) has been performed on Image J, Java Image processing program (NIH Image).

Discussion

Taken together, our present study suggests that HSP70 degradation is responsible for the severe erythroid phenotype observed in RPL5+/Mut and RPL11+/Mut when compared with RPS19+/Mut DBA. Indeed, both HSP70 dependent increased apoptosis and delay in erythroid differentiation in patients carrying a mutation in RPL5 or RPL11 gene enhanced the severity of the erythroid hypoplasia which we have repeatedly noted in erythroid culture from this subset of patients. The rescue of erythroid proliferation and differentiation in association with decreased apoptosis following overexpression of HSP70 validates our thesis. It is interesting to note that in our French cohort of DBA patients individuals with a mutation either in RPL5 or RPL11 gene (n = 41) exhibited a significantly higher level of a malformative syndrome (P = .0002) compared with patients who carried a mutation in RPS19 gene (n = 66). In addition, evolution to treatment independency is less in DBA patients who carry a mutation in RPL5 or RPL11 gene compared RPS19 (6 vs 10 patients) (data not shown). In spite of difficulties in establishing a phenotype/genotype correlation in DBA as in many constitutional rare diseases, the severity of the malformative syndrome in RPL5 and RPL11 DBA patient phenotype that been already previously reported20,42-44 and confirmed in our large patient cohort, the gene modifiers or the genetic mechanisms for increased severity have not been identified.44 Our study provides evidence that HSP70 may be one of the major genetic modifier of disease severity. However, the reasons why HSP70 expression level is dependent on the presence or not in a DBA patient of a mutation in RPS19 gene are still to be defined. Other pathways may be involved and indeed, it has been recently shown in shRNA-RPS19 deficient erythroid progenitors that the activation of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) through p38 MAPK phosphorylation could play a role in decreased GATA1 expression.45 TNF-α acting via S100A8 and S100A9 proteins of the innate immune system has recently been shown to be involved in the 5q- MDSs.46 We cannot exclude the possibility that 1 or more additional factors interacting with HSP70 depending on the specific RP mutated gene may be modulating the different phenotypes.

HSP70 is a stress inducible protein, a member of the large Heat Shock Protein family, which has been shown to be a major erythroid anti-apoptotic protein.34 HSP70 maintains BcL-XL, the antiapoptotic factor in synergy with EPO. In addition, upon EPO stimulation, during terminal erythroid differentiation, the chaperone HSP70 enters the nucleus, binds GATA1, and protects it from caspase-3 mediated proteolysis.34 HSP70 limits caspase-3 activation by interacting with Apaf-1, limiting the apoptosome formation.47,48 During apoptosis activation, in TF-1 erythroid cells, upregulated HSP70 is able to bind the mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor, sequestrating it into the cytosol in order to limit apoptosis.49,50 HSP70 is thus critically involved during erythropoiesis with regards to cell survival and erythroid differentiation.

Although previous studies have shown a role for HSP70 during terminal erythroid differentiation,34-36 our present findings suggest an important role for HSP70 in earlier erythroid progenitor proliferation in DBA. Specifically, we have documented that in RPL5+/Mut and RPL11+/Mut DBA cells, HSP70 is degraded by the proteasome machinery resulting in GATA1 cleavage, a block in the proliferation of erythroid progenitors and an induction of apoptosis, ultimately, leading to a decrease in BFU-E and CFU-E progenitors.

These results extend the list of human disorders of erythropoiesis in which GATA1 protection by HSP70 is defective,33-36 both in early erythroid progenitors (DBA) and in terminal erythroid differentiation (thalassemias and MDS) where apoptosis is a feature. The present findings provide additional mechanistic insights into the erythroid tropism of DBA.

Although p53-independent pathways do exist,51-53 p53 activation plays a central role in apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in DBA erythroid cells.37,54 The activation of p53 could be mediated by either binding of some ribosomal proteins to MDM2, which inhibits the E3 ubiquitin ligase function of this protein,55,56 or to RPL11 recruitment on the promoter of CBP/p300 gene whose product is a transcriptional coactivator of p53 and p53-regulated genes, including p21 gene.57 An additional mechanism of p53 activation recently documented in 5q- MDSs involves the TNF-α pathway in response to secreted S100A8 and S100A9, 2 proteins of the innate immune system.46 Finally, the decreased expression of GATA1 could also favor p53 activation.41 Our results argue for these latter mechanisms with p53 activation being a consequence of the downregulation of GATA1 in response to HSP70 defect in RPL5+/Mut and RPL11+/Mut erythroid cells.

The involvement of HSP70 in DBA pathophysiology adds additional complexity to the various mechanisms thought to play a role in DBA pathophysiology, which include (1) the ribosome maturation defect,12 resulting in the p53 stabilization responsible for cell cycle arrest and increased apoptosis leading at least in part to the erythroblastopenia37,54 ; (2) the selective translation defect of specific transcripts such GATA131 and BAG1, CSDE151 ; (3) the autophagy58,59 ; and (4) the imbalance between decreased globin synthesis and free heme excess (L.D.C., DBA foundation consensus conference, 6 March 2016, and Yang et al60 ), which generates reactive oxygen species and subsequent increase in cell toxicity and apoptosis of erythroid progenitors and precursors. The balance between each of mechanisms and perhaps others need to be further deciphered to account for the variable and heterogeneous severity of the disease phenotype. It is very likely that HSP70 in addition to GATA1 plays a key role in accounting erythroid defect, which is the hallmark of DBA.

Yet, the molecular events leading to HSP70 defect observed in RPL5+/Mut and RPL11+/Mut erythroid cells remain to be fully deciphered. Whatever these events might be, the role of HSP70 downregulation in the pathophysiology of severe DBA erythroid phenotypes and the ability to rescue erythroid proliferation and differentiation defect by overexpressing HSP70 in erythroid cells of various DBA-affected patients suggest that therapeutic approaches that would increase HSP70 expression in the nucleus of erythroid cells undergoing differentiation, for example, through blockade of its nuclear export, may be potentially beneficial for patients.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the patients affected with DBA and their families, the French DBA patients association “AFMBD,” the Maria Daniella Arturi and the DBA foundations. The authors honor Gil Tchernia for his inspiration, scientific discussions, and perpetual interest in DBA. The authors thank Isabelle Marie for her work in the French DBA registry and Julie Galimand, Hélène Bourdeau, and Laurène Guion for their work in DBA patient mutation screening analysis and the primer and probe design (Hematology Laboratory, R. Debré Hospital, Paris, France).

This work was supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR): ANR-RIBOCRASH (ANR-2010-BLAN-SVSE1-111501); ANR-HSPathies-ANR-2012-BLAN-SVSE1; ANR-2015-AAP générique-CE12; the Laboratory of Excellence for red cells (LABEX GR-Ex)-ANR Avenir-11-LABX-0005-02 (M.G. [funding for his PhD]); the French National PHRC OFABD (DBA registry and molecular biology)-2008-2012-2016; the “Fondation pour la Recherche médicale” (H.M. [funding for her PhD]); the Fondation ARC pour la recherche contre le cancer (M.G. and H.M. [funding for their PhDs]); and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health (grant DK32094).

Authorship

Contribution: L.D.C., E.S., W.V., and O.H. conceived the project; M.G., S.R., N.K., and H.M. performed the research; M.D. performed the ImageStream experiments with M.G.; M.S. and M.G. performed the IP experiments under the supervision of C.G.; T.L. provided the clinical data and patients samples; N.M. and A.N. provided scientific input and mentored N.K. for the erythroid cell culture synchronization experiments; P.G. performed the statistical analysis; M.G., S.R., N.K., H.M., M.D., M.S., L.D.C., E.S., W.V., and O.H. analyzed the data; and L.D.C., E.S., O.H., and W.V. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

A list of the members of the French Society of Hematology (SFH) and the French Society of Immunology and Hematology (SHIP) appears in “Appendix.”

Correspondence: Lydie Da Costa, Hôpital Robert Debré, Service d’Hématologie Biologique, 48 Blvd Sérurier, 75019 Paris, France; e-mail: lydie.dacosta@aphp.fr.

Appendix: study group members

The members of the French Society of Hematology (SFH) and French Society of Immunology and Hematology (SHIP) are: T.L., W.V., O.H., E.S., and L.D.C., along with the following members who provided blood samples from their affected DBA patients: M. P. Castex (CHU Toulouse), F. Fouyssac (CHU Nancy), C. Oudot (CHU Limoges), O. Minckes (CHU Caen), M. L. Menard (CH Sens), B. Pautard (CHU Amiens), and E. Tarral and V. Giacobbi-Milet (CH Le Mans).

References

Author notes

M.G. and S.R. contributed equally to this study.

![Figure 1. HSP70 expression level in human erythroid cell culture from DBA patients’ peripheral blood CD34+ cells and from cord blood CD34+ depleted in RPS19, RPL5, or RPL11 after shRNA infection. (A) Immunoblots of HSP70 and procaspase-3 at day 10 of erythroid cell culture (20 000 cells) from CD34+ peripheral blood from DBA-affected patients carrying various RP gene mutations: RPL5Mut/+ (UPN#412), RPL11Mut/+ (UPN#587), and RPS19Mut/+ (UPN#987, UPN#251, UPN#35) DBA-affected patients compared with the healthy controls (Co). HSP70 and procaspase-3 expression levels have been compared with β-actin expression. Molecular weight (Mr). (B) Immunoblots of HSP70 and procaspase-3 at day 7 of erythroid cell culture (50 000 cells) from cord blood CD34+ infected with various shRNAs against RPS19 (shRPS19), RPL5 (shRPL5-1 and shRPL5-2), and RPL11 (shRPL11) compared with noninfected CD34+ (Co) and Scramble (SCR). Representative of 5 independent experiments. Quantification of HSP70 protein immunoblot band intensity by ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health [NIH]) compared with β-actin from the 5 independent experiments is represented lower. (C) Study of HSP70 and GATA1 expression by immunostaining and analyzed by confocal microscopy at day 10 of erythroid cell culture from cord blood CD34+ infected with various shRNAs against RPS19 (shRPS19), RPL5 (shRPL5), and RPL11 (shRPL11) compared with noninfected CD34+ (Co). Shown are HSP70, GATA1, DAPI, and merged HSP70 and GATA1 stainings. Original magnification ×60. Scale bar represents 10 μm. (D) Study of HSP70 expression normalized to β-actin at day 6 of synchronized BFU-E and CFU-E progenitors obtained from cord blood CD34+ infected with various shRNAs against RPS19 (shRPS19), RPL5 (shRPL5), and RPL11 (shRPL11) compared with noninfected CD34+ (Co) and Scramble (SCR). Left: HSP70 expression after quantification of each immunoblot band by ImageJ software (NIH) compared with β-actin, in control BFU-E compared with shRPS19 and shRPL11 BFU-E (1 experiment-immunoblot in supplemental Figure 2E). Right top: HSP70 expression level after quantification of each immunoblot band by ImageJ software (NIH) compared with β-actin obtained in synchronized BFU-E and CFU-E. Right bottom: Immunoblot of HSP70 expression level in the synchronized BFU-E and CFU-E erythroid progenitors in each condition (20 000 cells/lane).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/1/22/10.1182_bloodadvances.2017008078/3/m_advances008078f1.jpeg?Expires=1765892202&Signature=FdOfPQno2OY2NVtC9Iha9KuZea7bdd52dFP3Mz3ApC7Sdm4ZQOL58~Lmt9r07Ny682NlCGwoQXBEijTv1WHlx4ouIFN0jQEU5ircg~1tH-fIOlmBxFpelpNDXHO7EX7rdsTbSZBN6P7-LnX2yC0xSkd3isal-kCfRX7jaiIg-WesSoZ2qYE9Yk79TFbfXFI5fLFvj1NQLF9k1N4d5i-QHXGzuob0eMEY~AU9GYYa63ussWtLSxIa-5wLVrx4uMJBV4-Mok6crsrdiL7eRvQsDOZgjsDRW149fDxnbib4o0HEIgRaUNWNzQpsJNuX42SIalHtsFYg2tLAEO3lc9Sq2w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)