Key Points

Treatment resistance in ITP has been linked to autoantibody-producing long-lived plasma cells, emphasizing the role of CD38 depletion.

CD38 antibody daratumumab demonstrated short- and long-term efficacy with an acceptable safety profile in patients with ITP.

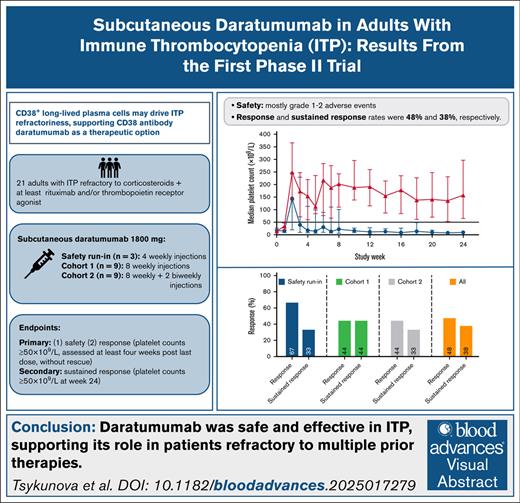

Visual Abstract

Resistance to B-cell–targeted therapies in immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) has been linked to persistence of autoantibody-producing CD38+ long-lived plasma cells. CD38 antibody daratumumab has been proposed as a potential therapy for ITP. This multicenter, open-label, phase 2 study evaluated safety and efficacy of daratumumab in 21 patients with previously treated ITP. Following a safety run-in, 2 dosing cohorts received 8 and 10 subcutaneous injections of 1800 mg daratumumab weekly, respectively. Primary end points were safety and response (2 consecutive platelet counts ≥50 × 109/L at week 12 for the safety run-in/cohort 1, and at week 16 for cohort 2). At baseline, median platelet count was 17 × 109/L, median number of prior therapies was 4. Most treatment-emergent adverse events were transient grade 1 to 2, most commonly infections (38%). Two patients (4.7%) experienced grade 3 adverse events, 1 infusion-related reaction, and 1 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection with acute renal failure. Ten patients (48%) met the primary efficacy end point. Sustained response (2 consecutive platelet counts ≥50 × 109/L at week 24) was achieved in 8 patients (38%), of whom 2 later relapsed. Response and relapse rates did not differ between cohorts. Patient-reported quality of life measured by 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey improved in responding patients. Daratumumab decreased immunoglobulin levels in all patients, and substantially reduced CD38+ cells in peripheral blood and bone marrow. There was no significant difference in antiplatelet antibodies between responders and nonresponders. This study confirms CD38 as an important target in ITP. This trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT04703621, and at the European Clinical Trial Register (EudraCT #2019-004683-22).

Introduction

Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is an acquired autoimmune bleeding disorder characterized by isolated thrombocytopenia in the absence of other thrombocytopenia-associated disorders.1 ITP is believed to result from a loss of immune tolerance toward platelet antigens. Immune-mediated attack by antibodies and T cells causes accelerated peripheral platelet destruction and impaired production, resulting in thrombocytopenia.2

Corticosteroids are the first-line treatment choice, but few patients achieve long-term remissions.3 Consequently, most patients with ITP require second-line therapies, including thrombopoietin receptor agonist (TPO-RA) or immunomodulatory agents. Nevertheless, patients respond variably to available second-line therapies, and many relapse after an initial response. One such example is the CD20 antibody rituximab. Despite initial response of 60%, half of the responders lose response within 2 to 5 years.4,5 Mechanisms associated with failure/relapse include inadequate B-cell clearance, persistence of autoreactive CD20-CD19+ memory B cells, and emergence of long-lived splenic and bone marrow plasma cells.6-9 Importantly, long-lived plasma cells in the bone marrow show overexpression of antiapoptotic genes and do not express CD20, and thus may contribute to relapse from and resistance to treatments like rituximab and splenectomy.8

Based on these observations, plasma cell-depleting therapy is a promising potential treatment for patients with ITP with inadequate response to second-line therapies. The CD38 monoclonal antibody, daratumumab, has previously shown therapeutic effects in refractory autoimmune conditions,10,11 and small case series have shown efficacy in ITP.12-14 Beyond plasma cells and plasmablasts, daratumumab targets other CD38-expressing cells, including subsets of B and T cells, dendritic cells, and natural killer cells.15

More data on the safety, efficacy, and total cumulative dose of daratumumab were needed to assess its potential as a treatment for ITP in adults before conducting the randomized trial. This led to the conduct of the hypothesis-generating DART trial.

Materials and methods

Study design

Daratumumab as a treatment for adult ITP (the DART Study) was an investigator-initiated, multicenter, open-label, phase 2 study of subcutaneous daratumumab in patients with ITP, conducted in 6 hematology centers in Norway, Denmark, and France, with a primary aim to evaluate the safety and efficacy of subcutaneous daratumumab in ITP.

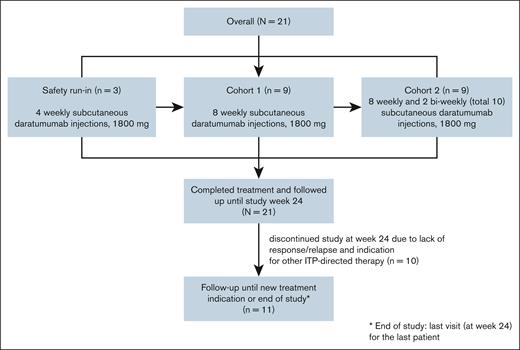

The trial consisted of an initial safety run-in phase involving the first 3 participants, and 2 total dose-increasing cohorts of 9 patients each to assess the impact of total dose on response rates (Figure 1).

CONSORT flow diagram of the study. The first 3 patients participated in the safety run-in cohort, and received 4 weekly subcutaneous daratumumab injections of 1800 mg. Each patient in the safety run-in cohort was treated and observed individually for 4 weeks after treatment. In the subsequent phases of the study, 9 patients were included in cohort 1, and received 8 weekly subcutaneous daratumumab injections. The last 9 patients were included in cohort 2, and received 8 weekly subcutaneous daratumumab injections, followed by 2 biweekly injections (total of 10 injections). The primary end point, response, was evaluated at week 12 in the safety run-in and cohort 1, and week 16 in cohort 2. All patients were followed until study week 24. Patients with sustained response and nonresponders without a need for other ITP-directed therapy were followed until the end of the study.

CONSORT flow diagram of the study. The first 3 patients participated in the safety run-in cohort, and received 4 weekly subcutaneous daratumumab injections of 1800 mg. Each patient in the safety run-in cohort was treated and observed individually for 4 weeks after treatment. In the subsequent phases of the study, 9 patients were included in cohort 1, and received 8 weekly subcutaneous daratumumab injections. The last 9 patients were included in cohort 2, and received 8 weekly subcutaneous daratumumab injections, followed by 2 biweekly injections (total of 10 injections). The primary end point, response, was evaluated at week 12 in the safety run-in and cohort 1, and week 16 in cohort 2. All patients were followed until study week 24. Patients with sustained response and nonresponders without a need for other ITP-directed therapy were followed until the end of the study.

The primary efficacy end point was evaluated at week 12 for the safety run-in and cohort 1, and week 16 for cohort 2, to avoid a possible effect of corticosteroid premedication on platelet counts. All patients were followed until week 24 to assess the sustained response rate and other secondary end points. Patients with sustained responses and nonresponders not requiring initiation of additional platelet-elevating therapy were followed until the end of the study (last visit for the last patient).

Patients

Patients with primary ITP were eligible if they were aged ≥18 years, had a platelet count of ≤30 × 109/L, had failed to respond or relapsed after corticosteroid treatment and at least 1 second-line therapy, including TPO-RA or rituximab (last infusion ≥24 weeks before study inclusion). For the safety run-in phase, a platelet counts of 15 × 109/L to 30 × 109/L was required. The dose of corticosteroids and TPO-RAs had to remain stable over the 2 weeks prior to inclusion without increase during the study period. Rescue therapy (IV immunoglobulin, corticosteroids, anti-D and platelet transfusions) was allowed until the day of the administration of the last injection of study treatment; its use after that qualified the patient as a nonresponder. Details on eligibility criteria are presented in the supplemental Appendix.

The trial was conducted according to the International Council on Harmonization Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethics committee of each participating institution approved the trial protocol. The independent data and safety monitoring board provided oversight. All patients provided written informed consent before trial entry.

Treatment

Subcutaneous daratumumab, 1800 mg per dose, was administered weekly for 4 weeks for the safety run-in, weekly for 8 weeks for cohort 1, and weekly for 8 weeks followed by every 2 weeks at weeks 10 and 12 for cohort 2.

The 3 safety run-in participants were treated and observed individually for 4 weeks after treatment. To investigate whether a higher cumulative daratumumab dose could lead to a higher and/or longer response, 2 successive dosing cohorts with 9 patients each were defined, with cohort 2 receiving a 25% higher total dose.

Progress to the next participant in the safety run-in phase and the decision to initiate each cohort was based on safety evaluation conducted by the Data and Safety Monitoring Board.

Premedication included antihistamines (diphenhydramine 50 mg or equivalent) and paracetamol (acetaminophen 1000 mg). Methylprednisolone 100 mg or equivalent preceded the first injection, and was reduced to 60 mg for the second and subsequent injections. In addition, methylprednisolone 20 mg (or equivalent) was administered for 2 consecutive days following the first 3 daratumumab injections only. Montelukast (10 mg) was given only before the first daratumumab injection.

Methods

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was assessed using the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey Version 1 (SF-36v1)18,19 and the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI- 20) questionnaire to evaluate fatigue.20 Participants answered the questionnaires before initiation of therapy, 4 weeks after the last treatment, and at study week 24. Minimal important difference (MID) values estimated for the EXTEND study population were used to evaluate the clinical significance of changes in SF-36 domains.21

Blood for study-specific analyses was taken only at Norwegian and French study centers.

Mononuclear cells for evaluation of CD38 depletion were cryopreserved from blood and bone marrow at screening, and 4 weeks after the last daratumumab infusion, that is week 12 for the safety run-in and cohort 1, and week 16 for cohort 2, and from blood at study week 24. Flow cytometric analysis of mononuclear cells for evaluation of CD38 depletion was performed with cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells and bone marrow mononuclear cells enriched for live cells by magnetic depletion of dead cells (Dead Cells Removal Kit, Miltenyi) in the presence of citrate buffer. At least 1 million cells per patient sample, healthy donor peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and VeriCells were seeded in a 96-well plate. Cells were washed, and each well was stained with Live/Dead Zombie Near-IR (BioLegend) diluted in phosphate-buffered saline. Cells were washed and stained with pretitrated CD38 antibody (clone HIT-2, BD Biosciences) and B-cell antibody panel for 30 minutes at 4°C.22 Cells were washed twice before fixation and immediate acquisition on a SONY ID7000 flow cytometer. The staining was analyzed using FlowJo v10 software (BD Life Sciences).

Antiplatelet antibody test was performed for the Norwegian patients only. Platelet immunoglobulin G (IgG) autoantibodies to glycoproteins (GPs) IIb/IIIa, Ib/IX, Ia/IIa, and V on patients’ platelets were evaluated using in-house indirect and direct monoclonal antibody immobilization of platelet antigens assay (MAIPA).23,24 Briefly, platelets isolated from EDTA blood tubes were tested in duplicates using 20 × 106 platelets per well. Donor platelets (blood group O) were incubated with 50 μL patient plasma (for indirect MAIPA), or patient platelets were incubated with autologous plasma (for direct MAIPA). Monoclonal antibodies specific for GPIIIa/CD61 (Y2/51), GPIb/CD42b (SZ2), GPIa/CD49b (Gi9), and GPV/CD42d (SW16) were used at 5 μg/mL. For detection, goat anti-human IgG (HRP) and tetramethylbenzidine substrate were used, and the reaction was stopped with 0.5 M H2SO4. Optical density (OD) was read at 450 nm. For indirect MAIPA, positive cutoff values were mean OD (negative control) +2 standard deviations of control plasma in the set-up. For direct MAIPA, OD values ≥0.15 to 0.2 were evaluated as weakly reactive, while a restrictive positive cutoff was set to OD ≥0.2.

For some samples, the numbers of platelets were not sufficient for direct MAIPA, and the available platelets were used (>5 × 106 platelets per well): if negative in the test, results were considered inconclusive.

Antidaratumumab antibodies were analyzed using the KRIBIOLISA antidaratumumab enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Eagle Biosciences, Amherst, NH). CD38 expression (anti-CD38, clone HIT2; BD Biosciences) was measured on an Attune NxT (Thermo Fisher) or a SONY ID7000 flow cytometer, and analyzed using FlowJo v10 software (BD Life Sciences).

More details on blood- and bone marrow sampling are presented in the supplemental Appendix.

End points

The main primary end points were safety and efficacy of subcutaneous daratumumab. Safety was assessed as the number and severity of adverse events grade ≥2 during the study. Adverse events were recorded at least until week 24, and as long as the patient remained in the study.

The primary efficacy end point, response, was defined as 2 consecutive platelet counts ≥50 × 109/L (measured ≥24 hours apart), assessed at least 4 weeks after the last daratumumab injection (week 12 for safety run-in and cohort 1, and week 16 for cohort 2), given the high corticosteroid doses in standard daratumumab premedication to allow for corticosteroid washout.

Secondary efficacy end points were rates of sustained response defined as 2 consecutive platelet counts ≥50 × 109/L (measured ≥24 hours apart) at study week 24, duration of response, time to treatment failure, and number of bleeding episodes per patient.

Exploratory outcomes were time from first treatment to the first platelet count ≥50 × 109/L, rates of complete response (platelet count ≥100 × 109/L) and partial response (platelet count >30 × 109/L but <50 × 109/L, or at least doubling of platelet count from baseline), evaluation of patient-reported outcomes, pretreatment and posttreatment levels of antiplatelet antibodies, and depletion efficacy of CD38+ immune cells in blood and bone marrow. Detailed description of the end points is provided in the supplemental Appendix.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed for all enrolled patients. Baseline characteristics are presented using descriptive statistics. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for evaluation of primary and secondary end points were calculated using the Clopper-Pearson method. Time-to-event estimates were evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method. No replacement of missing data was performed.

No formal hypothesis was planned in this study, as the statistical power was insufficient to detect differences between dose groups.

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism (version 9.0.0), R Statistical Software (version 4.4.2), and STATA/SE v.18.0.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between January 2021 and September 2023, 21 patients were enrolled. The data cutoff for analysis was 12 March 2024, 6 months after last enrollment. All patients completed study treatment, and were available for analysis of the primary and secondary end points.

Demographics are described in Table 1. Median age was 51 years (range, 19-77 years), and 66.7% were males. Median number of previous ITP-directed therapies was 4 (range, 2-11). Nineteen patients (90%) had previously responded to corticosteroids at least once. Five patients (23.8%) had received a splenectomy, and 16 had previously received rituximab. Thirteen (62%) patients received concurrent medication at baseline: corticosteroids (14%), TPO-RA (24%), or combination (24%).

Patient and disease characteristics at baseline

| Characteristics . | All patients (N = 21) . | Safety run-in (n = 3) . | Cohort 1 (n = 9) . | Cohort 2 (n = 9) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR), y | 51 (34-65) | 55 (33-75) | 51 (36-67) | 49 (33-59) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 14 (66.7) | 2 (66.7) | 5 (55.6) | 7 (77.8) |

| Female | 7 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 4 (44.4) | 2 (22.2) |

| Median BMI (IQR), kg/m2 | 29.3 (26.0-33.3) | 35.0 (28.0-42.2) | 29.4 (26.0-32.2) | 28.7 (25.3-33.3) |

| Median platelet count at screening (IQR), ×109/L | 17.0 (10.0-20.0) | 17.0 (16.0-26.0) | 19.0 (15.0-22.0) | 16.0 (10.0-19.0) |

| Median duration of ITP∗ (IQR), mo | 60.5 (13.5- 231.7) | 108.8 (13.5-136.8) | 18.3 (7.3-60.5) | 231.4 (42.0- 272.9) |

| Median number of different prior ITP treatments (range) | 4 (2-11) | 5 (3-6) | 4 (2-9) | 4 (3-11) |

| Prior ITP therapy, n (%) | ||||

| Corticosteroids | 21 (100) | 3 (100) | 9 (100) | 9 (100) |

| IVIG | 14 (67) | 2 (67) | 5 (56) | 7 (78) |

| Rituximab | 16 (76) | 3 (100) | 6 (67) | 7 (78) |

| TPO-RA† | 18 (86) | 3 (100) | 8 (67) | 7 (78) |

| Fostamatinib | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (11) |

| Rilzabrutinib | 1 (5) | 1 (33) | 0 | 0 |

| Azathioprine | 2 (10) | 0 | 1 (11) | 1 (11) |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 2 (10) | 0 | 0 | 2 (22) |

| Dapsone | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (11) |

| Danazol | 1 (5) | 0 | 1 (11) | 0 |

| Cyclosporine | 2 (10) | 0 | 0 | 2 (22) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (11) |

| Splenectomy | 5 (24) | 0 | 2 (22) | 3 (33) |

| Response to previous steroid therapy | 19 (90) | 2 (67) | 9 (100) | 8 (89) |

| Concomitant ITP-directed therapy (at the date of the first daratumumab injection), n (%) | ||||

| Corticosteroid monotherapy | 3 (14) | 0 | 0 | 3 (33) |

| TPO-RA monotherapy | 5 (24) | 1 (33) | 2 (22) | 2 (22) |

| TPO-RA and corticosteroids combined | 5 (24) | 2 (67) | 1 (11) | 2 (22) |

| WHO bleeding score at baseline, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 11 (52) | 1 (33) | 8 (89) | 2 (22) |

| 1 | 9 (43) | 2 (67) | 1 (11) | 6 (67) |

| 2 | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (11) |

| 3/4/5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Median IgG level at baseline (IQR), g/L | 10.1 (8.6-12.7) | 10.1 (9.6-12.0) | 12.4 (11.7-14.3) | 8.6 (6.3-10.1) |

| Characteristics . | All patients (N = 21) . | Safety run-in (n = 3) . | Cohort 1 (n = 9) . | Cohort 2 (n = 9) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR), y | 51 (34-65) | 55 (33-75) | 51 (36-67) | 49 (33-59) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 14 (66.7) | 2 (66.7) | 5 (55.6) | 7 (77.8) |

| Female | 7 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 4 (44.4) | 2 (22.2) |

| Median BMI (IQR), kg/m2 | 29.3 (26.0-33.3) | 35.0 (28.0-42.2) | 29.4 (26.0-32.2) | 28.7 (25.3-33.3) |

| Median platelet count at screening (IQR), ×109/L | 17.0 (10.0-20.0) | 17.0 (16.0-26.0) | 19.0 (15.0-22.0) | 16.0 (10.0-19.0) |

| Median duration of ITP∗ (IQR), mo | 60.5 (13.5- 231.7) | 108.8 (13.5-136.8) | 18.3 (7.3-60.5) | 231.4 (42.0- 272.9) |

| Median number of different prior ITP treatments (range) | 4 (2-11) | 5 (3-6) | 4 (2-9) | 4 (3-11) |

| Prior ITP therapy, n (%) | ||||

| Corticosteroids | 21 (100) | 3 (100) | 9 (100) | 9 (100) |

| IVIG | 14 (67) | 2 (67) | 5 (56) | 7 (78) |

| Rituximab | 16 (76) | 3 (100) | 6 (67) | 7 (78) |

| TPO-RA† | 18 (86) | 3 (100) | 8 (67) | 7 (78) |

| Fostamatinib | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (11) |

| Rilzabrutinib | 1 (5) | 1 (33) | 0 | 0 |

| Azathioprine | 2 (10) | 0 | 1 (11) | 1 (11) |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 2 (10) | 0 | 0 | 2 (22) |

| Dapsone | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (11) |

| Danazol | 1 (5) | 0 | 1 (11) | 0 |

| Cyclosporine | 2 (10) | 0 | 0 | 2 (22) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (11) |

| Splenectomy | 5 (24) | 0 | 2 (22) | 3 (33) |

| Response to previous steroid therapy | 19 (90) | 2 (67) | 9 (100) | 8 (89) |

| Concomitant ITP-directed therapy (at the date of the first daratumumab injection), n (%) | ||||

| Corticosteroid monotherapy | 3 (14) | 0 | 0 | 3 (33) |

| TPO-RA monotherapy | 5 (24) | 1 (33) | 2 (22) | 2 (22) |

| TPO-RA and corticosteroids combined | 5 (24) | 2 (67) | 1 (11) | 2 (22) |

| WHO bleeding score at baseline, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 11 (52) | 1 (33) | 8 (89) | 2 (22) |

| 1 | 9 (43) | 2 (67) | 1 (11) | 6 (67) |

| 2 | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (11) |

| 3/4/5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Median IgG level at baseline (IQR), g/L | 10.1 (8.6-12.7) | 10.1 (9.6-12.0) | 12.4 (11.7-14.3) | 8.6 (6.3-10.1) |

BMI, body mass index; IVIG, IV immunoglobulin; WHO, World Health Organization.

The duration of ITP was defined as the time from date of ITP diagnosis to the date of baseline evaluation.

TPO-RA include eltrombopag, avatrombopag, and romiplostim.

Safety end points

During the study, 9 patients (43%) experienced at least 1 treatment-related adverse event, all were transient (Table 2). The most common treatment-related adverse events were infusion-related reactions (IRRs), occurring in 3 patients (14%), injection site reactions (9.5%), and diarrhea (9.5%). All IRRs were related to the first injection, and resolved within 24 hours. Infections were the most common treatment-emergent adverse events (38%; supplemental Table 1). One patient had several upper respiratory tract infections managed with oral antibiotics and without hospitalization.

Treatment-related adverse events

| Adverse event . | No. of patients (%) with treatment-related adverse events∗ . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade . | Grade 1 . | Grade 2 . | Grade 3† . | |

| Any adverse event | 9 (42.9) | 4 (19.0) | 5 (23.8) | 1 (4.7) |

| IRRs | 3 (14.3) | 0 | 2 (9.5) | 1 (4.7) |

| Urticaria | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 1 (4.7) | 0 |

| Fever | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 1 (4.7) | 0 |

| IRR | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.7) |

| Injection site reaction | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Erythematous rush | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Injection site discoloration | 1 (4.7) | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Infections | 1 (4.7) | 1 (4.7) | 1 (4.7) | 0 |

| Upper respiratory tract infections | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 1 (4.7) | 0 |

| Sinusitis | 1 (4.7) | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 2 (9.5) | 0 | 2 (9.5) | 0 |

| Headache | 1 (4.7) | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 1 (4.7) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 1 (4.7) | 0 |

| Weight gain | 1 (4.7) | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Adverse event . | No. of patients (%) with treatment-related adverse events∗ . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade . | Grade 1 . | Grade 2 . | Grade 3† . | |

| Any adverse event | 9 (42.9) | 4 (19.0) | 5 (23.8) | 1 (4.7) |

| IRRs | 3 (14.3) | 0 | 2 (9.5) | 1 (4.7) |

| Urticaria | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 1 (4.7) | 0 |

| Fever | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 1 (4.7) | 0 |

| IRR | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.7) |

| Injection site reaction | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Erythematous rush | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Injection site discoloration | 1 (4.7) | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Infections | 1 (4.7) | 1 (4.7) | 1 (4.7) | 0 |

| Upper respiratory tract infections | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 1 (4.7) | 0 |

| Sinusitis | 1 (4.7) | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 2 (9.5) | 0 | 2 (9.5) | 0 |

| Headache | 1 (4.7) | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 1 (4.7) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 1 (4.7) | 0 |

| Weight gain | 1 (4.7) | 1 (4.7) | 0 | 0 |

Relatedness to treatment was determined by the study investigators. Four patients had >1 treatment-related adverse event.

In total, 3 adverse events of grade 3 were reported in 2 patients. Only 1 (IRR) was related to treatment. The second patient contracted severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection complicated with acute renal failure. No grade 4 or grade 5 adverse events appeared during the study.

Two patients experienced grade 3 adverse events. One had an IRR. The second patient experienced severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection complicated by acute renal failure, unrelated to the study treatment as considered by investigator. There were no grade 4 adverse events or deaths among participants, and no treatment-related thrombotic events. None of the patients discontinued study treatment.

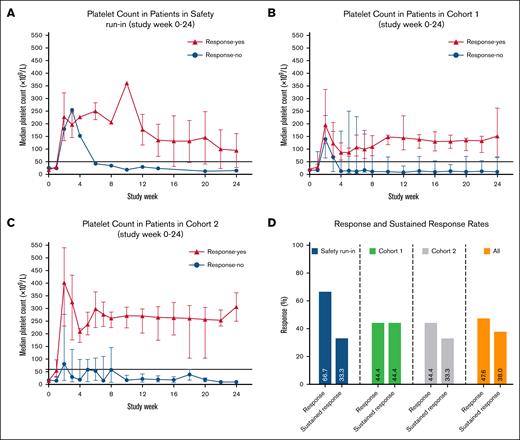

Efficacy end points

All 21 included patients were evaluated for efficacy. The primary end point, response, was met in 10 patients (48% [95% CI, 25.7-70.2]). This included 2 of 3 patients in the safety run-in, 4 of 9 patients (44% [95% CI, 13.7-78.8]) in cohort 1, and 4 of 9 patients (44% [95% CI, 13.7-78.8]) in cohort 2 (Table 3). One additional patient in cohort 1 responded shortly after the primary end point evaluation, at week 14. Five of 11 responding patients (45%) used concomitant medications at the time of the first daratumumab injection (2 were treated with TPO-agonist, 2 with prednisolone, and 1 with a combination of TPO-agonist and prednisolone). All responding patients discontinued concomitant ITP medication, and the median time to discontinuation was 6 weeks (range, 2-12 weeks). Eighteen (86%) patients achieved a platelet count of ≥50 × 109/L at least once between the date of the first study treatment and the primary end point evaluation, with median time to first platelet count ≥50 × 109/L of 7 days (range, 6-10 days).

Efficacy end points

| End point . | All patients (N = 21) . | Cohort 1 (n = 9) . | Cohort 2 (n = 9) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary end point∗ | |||

| Response rate, n % (95% CI) | 10 48 (25.7-70.2) | 4 44 (13.7-78.8) | 4 44 (13.7-78.8) |

| Secondary end points | |||

| Sustained response rate, n % (95% CI) | 8 38 (18.1-61.6) | 4 44 (13.7-78.8) | 3 33 (7.4-70.0) |

| Median duration of response (range), mo | 21.5 (1.2-33.2) | 18.7 (3.2-26.2) | 8.1 (1.2-11.5) |

| Time to treatment failure (range), mo | 22.3 (1.2-33.2) | 18.7 (12.0-26.2) | 8.1 (1.2-11.5) |

| Median time from first daratumumab injection to first platelet count >50 × 109/L (range), d | 7 (6-10) | 6.5 (6-8) | 7 (6-10) |

| No. of patients with platelet count ≥100 × 109/L (complete response), n % (95% CI)† | 9 43 (21.8-66.0) | 3 33 (7.4-70.0) | 4 44 (13.7-78.8) |

| No. of patients with platelet count <50 × 109/L but >30 × 109/L (partial response), n % (95% CI)† | 1 5 (0.1-23.0) | 0 0 | 1 11 (0.3-48.2) |

| End point . | All patients (N = 21) . | Cohort 1 (n = 9) . | Cohort 2 (n = 9) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary end point∗ | |||

| Response rate, n % (95% CI) | 10 48 (25.7-70.2) | 4 44 (13.7-78.8) | 4 44 (13.7-78.8) |

| Secondary end points | |||

| Sustained response rate, n % (95% CI) | 8 38 (18.1-61.6) | 4 44 (13.7-78.8) | 3 33 (7.4-70.0) |

| Median duration of response (range), mo | 21.5 (1.2-33.2) | 18.7 (3.2-26.2) | 8.1 (1.2-11.5) |

| Time to treatment failure (range), mo | 22.3 (1.2-33.2) | 18.7 (12.0-26.2) | 8.1 (1.2-11.5) |

| Median time from first daratumumab injection to first platelet count >50 × 109/L (range), d | 7 (6-10) | 6.5 (6-8) | 7 (6-10) |

| No. of patients with platelet count ≥100 × 109/L (complete response), n % (95% CI)† | 9 43 (21.8-66.0) | 3 33 (7.4-70.0) | 4 44 (13.7-78.8) |

| No. of patients with platelet count <50 × 109/L but >30 × 109/L (partial response), n % (95% CI)† | 1 5 (0.1-23.0) | 0 0 | 1 11 (0.3-48.2) |

The primary end point response was defined as proportion of patients who achieve platelet count ≥50 × 109/L in 2 measurements (taken at least 24 hours apart) during week 12 after the first study drug injection for safety run-in and cohort 1, and week 16 for cohort 2, without having received rescue therapy for the last 4 weeks, or having had dose increment of TPO-RA or corticosteroids during the study period. The 95% CIs were based on the Clopper-Pearson method. The width of the CIs has not been adjusted for multiplicity, and should not be used to definitively infer efficacy.

Evaluation of complete and partial response displayed in this table was done at 12 weeks for patients in the safety run-in and cohort 1, and at week 16 for patients in cohort 2. Complete response was defined as platelet count ≥100 × 109/L. Partial response was defined as platelet count >30 × 109/L, but <50 × 109/L (or at least doubling of the platelet count from baseline).

Of 16 patients who had previously been treated with rituximab, 8 (50%) met the primary end point, and 6 out of 8 were still responding at week 24. Of those who previously responded to rituximab (n = 4), 3 showed a response to daratumumab at weeks 12/16, while 1 did not. By week 24, 2 prior rituximab responders maintained a response to daratumumab. Although the exact interval since rituximab was not consistently recorded, study eligibility required at least 24 weeks since the last dose; where available, the documented intervals were substantially longer.

None of the 5 patients who received splenectomy responded to daratumumab, whereas 11 of 16 patients who did not receive splenectomy did.

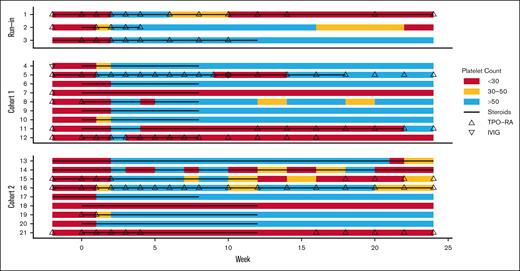

A sustained response defined as 2 consecutive platelet counts ≥50 × 109/L (measured ≥24 hours apart) at study week 24 was achieved in 8 patients (38% [95% CI, 18.1-61.6]), 1 from the safety run-in, 4 (44% [95% CI, 13.7-78.8]) from cohort 1, and 3 (33% [95% CI, 7.4-70.0]) from cohort 2 (Figures 2 and 3; supplemental Figure 1).

Platelet counts over time in patients included in (A) safety run-in, (B) study cohort 1, (C) cohort 2, and (D) response rates. (A) The median platelet count from screening through the 24-week treatment period is shown for the 3 patients in safety run-in, (B) 9 patients in cohort 1, (C) and 9 patients in cohort 2. Bars represent IQR. Horizontal lines at platelet counts of 50 × 109/L represent the threshold for response. (D) The bar diagram shows the percentage of patients who met the criteria for the primary (response) and secondary (sustained response) end points.

Platelet counts over time in patients included in (A) safety run-in, (B) study cohort 1, (C) cohort 2, and (D) response rates. (A) The median platelet count from screening through the 24-week treatment period is shown for the 3 patients in safety run-in, (B) 9 patients in cohort 1, (C) and 9 patients in cohort 2. Bars represent IQR. Horizontal lines at platelet counts of 50 × 109/L represent the threshold for response. (D) The bar diagram shows the percentage of patients who met the criteria for the primary (response) and secondary (sustained response) end points.

Swimmer plot of the duration of response in patients receiving subcutaneous daratumumab injection. Responses shown from baseline to study week 24, where week 1 is the week of the first daratumumab treatment. The colors indicate platelet count: <30 × 109/L (red); 30 × 109/L to 50 × 109/L (yellow); >50 × 109/L (blue). Black line indicates exposure to corticosteroids, including those used as a concomitant therapy and as a part of daratumumab premedication. At the point of evaluation of response, concomitant therapy was administered to 8 of 21 patients, including TPO-RA only (n = 1), corticosteroids (n = 2), both (n = 4), and TPO-RA with sirolimus (n = 1). At the point of evaluation for sustained response, concomitant therapy was administered to 8 of 21 patients, including TPO-RA (n = 3), corticosteroids (n = 1), both (n = 2), mycophenolate mofetil (n = 1), and TPO-RA with sirolimus (n = 1); none were responders.

Swimmer plot of the duration of response in patients receiving subcutaneous daratumumab injection. Responses shown from baseline to study week 24, where week 1 is the week of the first daratumumab treatment. The colors indicate platelet count: <30 × 109/L (red); 30 × 109/L to 50 × 109/L (yellow); >50 × 109/L (blue). Black line indicates exposure to corticosteroids, including those used as a concomitant therapy and as a part of daratumumab premedication. At the point of evaluation of response, concomitant therapy was administered to 8 of 21 patients, including TPO-RA only (n = 1), corticosteroids (n = 2), both (n = 4), and TPO-RA with sirolimus (n = 1). At the point of evaluation for sustained response, concomitant therapy was administered to 8 of 21 patients, including TPO-RA (n = 3), corticosteroids (n = 1), both (n = 2), mycophenolate mofetil (n = 1), and TPO-RA with sirolimus (n = 1); none were responders.

Median duration of follow-up was 10.4 months (range, 5.3-34.8 months) for the entire study population, 15.4 months (range, 5.5-29.2 months) in cohort 1, and 8.0 months (range, 5.3-15.2 months) in cohort 2.

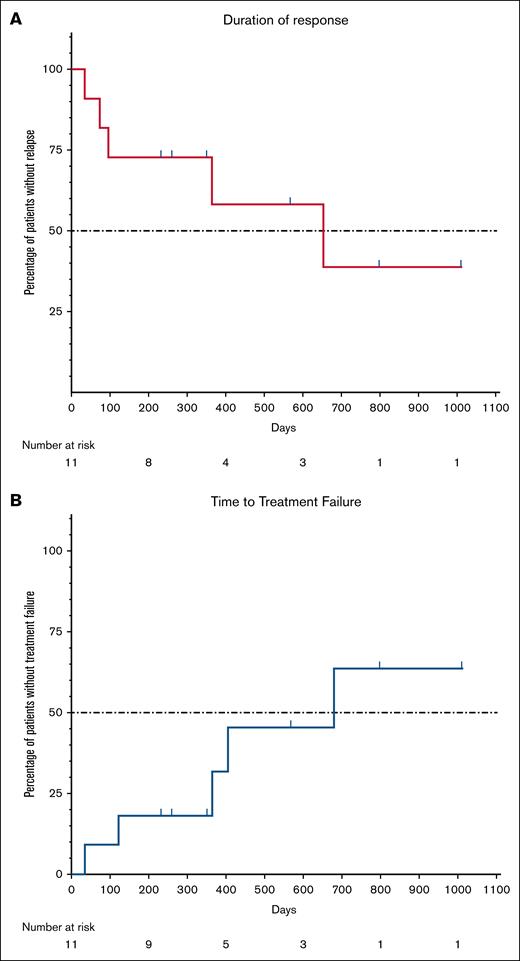

Median duration of response was 21.5 months (range, 1.2-33.2 months), and time to treatment failure was 22.3 months (range, 1.2-33.2 months; Figure 4). At end of the study, 6 patients (29%) maintained response without additional ITP-directed therapies; 1 from the safety run-in, 2 from cohort 1, and 3 in cohort 2.

(A) Duration of response and (B) time to treatment failure. Duration of response was defined as the duration of platelet count ≥50 × 109/L in 2 consecutive blood samples taken at least 24 hours apart, without having received any platelet-elevating therapy or having had dose increment of TPO-RA and/or corticosteroids, and starting from a minimum of 4 weeks following the last daratumumab injection. Loss of response was defined as platelet count <50 × 109/L after achieving response, in 2 consecutive blood samples taken at least 24 hours apart. Time to treatment failure was defined as a time with platelet count ≥50 × 109/L from 4 weeks after the last daratumumab injection to the first platelet count <30 × 109/L of 2 counts taken in 2 consecutive measurements at least 24 hours apart, or administration of any platelet-elevating therapy after achieving response.

(A) Duration of response and (B) time to treatment failure. Duration of response was defined as the duration of platelet count ≥50 × 109/L in 2 consecutive blood samples taken at least 24 hours apart, without having received any platelet-elevating therapy or having had dose increment of TPO-RA and/or corticosteroids, and starting from a minimum of 4 weeks following the last daratumumab injection. Loss of response was defined as platelet count <50 × 109/L after achieving response, in 2 consecutive blood samples taken at least 24 hours apart. Time to treatment failure was defined as a time with platelet count ≥50 × 109/L from 4 weeks after the last daratumumab injection to the first platelet count <30 × 109/L of 2 counts taken in 2 consecutive measurements at least 24 hours apart, or administration of any platelet-elevating therapy after achieving response.

Seven patients experienced WHO grade 2 bleeding episodes; none were related to treatment. One patient experienced macroscopic hematuria, and another experienced menorrhagia (supplemental Table 2).

Rescue medications were used in 2 patients (9.5%) during the study period, 1 during the first 24 weeks, and another during the later follow-up.

Patient-reported outcomes

Data regarding patient-reported outcomes at baseline and 4 weeks after the last daratumumab treatment are shown in supplemental Figures 2 and 3 and supplemental Tables 3 and 4. Compared with baseline, numerical improvement was observed for responders in all 8 dimensions of the SF-36 at 4 weeks after the completion of treatment. In 4 domains (role limitations due to physical health and emotional problems, energy/fatigue, and general health), the observed improvements were higher than MID values. In the fatigue-specific tool, MFI-20, a trend to improvement in the general fatigue domain was observed in responders compared with nonresponders, whereas in the 4 other domains, a very minor improvement in the domains of physical and mental fatigue was observed.

Changes in immunologic indicators

Efficacy of daratumumab-mediated immune cell depletion was evaluated longitudinally in 13 patients with cryopreserved cells derived from bone marrow and peripheral blood at screening and at primary end point evaluation, and in blood only at study week 24. The median reduction of CD38+ cells at primary end point evaluation was 91% (interquartile range [IQR], 73%-93%) in the peripheral blood, 90% (IQR, 69%-98%) in bone marrow, and 91% (IQR, 73%-93%) in the peripheral blood at week 24. No difference between cohorts in responders vs nonresponders was observed.

Serum Ig levels decreased after the administration of daratumumab in all patients (supplemental Table 5), with no association between magnitude of Ig decline and platelet response.

At baseline, only 3 of 7 of the responders (43%) and 4 of 9 of the nonresponders (44%) had antiplatelet antibodies with direct MAIPA (OD cutoff 0.15). Platelet autoantibodies were notably detectable in only 6 of 16 patients tested at baseline, with the more conservative cutoff OD 0.2. Four weeks after the last treatment, antiplatelet antibodies were still detectable in 2 responders (29%) and 2 nonresponders (22%; supplemental Table 6). All of the direct MAIPA negative/inconclusive patient samples were also negative in indirect MAIPA.

Antidrug (daratumumab) antibody samples were analyzed in 12 patients with no antibodies detected.

Discussion

In this phase 2 study, the anti-CD38 antibody daratumumab was administered subcutaneously to an ITP population previously treated with a median of 4 prior lines of therapy; two-thirds had been previously treated with both rituximab and TPO-RA, and ∼25% had failed splenectomy. The primary end point was achieved in 48% of the patients, with 1 additional patient achieving a response 2 weeks after the primary end point evaluation time point.

Treatment with subcutaneous daratumumab was associated with mainly mild to moderate and transient adverse events, with infections being the most common treatment-emergent adverse event. Infusion reactions were infrequent, manageable, and did not recur with subsequent daratumumab injections. While treatment with subcutaneous daratumumab led to a consistent, substantial decline in immunoglobulin levels in all study participants, only 1 patient developed recurrent infections requiring antimicrobial therapy. No grade 4 adverse events or deaths occurred, and none discontinued study treatment.

Recently, Chen et al reported the safety and efficacy of 8 weekly IV injections of anti-CD38 antibody CM313 in 22 previously treated patients with ITP.25 Similar to our study, the median number of previous therapies was 4. Compared with our patient cohort, patients in the CM313 study were younger (median age 36 vs 51 years), mostly female (76% vs 33%), had lower body mass index (median of 25.9 vs 29.3 kg/m2), shorter median ITP duration (27.0 vs 60.1 months), and only 36% had previously been treated with rituximab compared with 76% in our study. In the CM313 study, overall response at week 12 (platelet counts ≥30 ×109/L) was 86%, and durable sustained response was 64% at week 24, which was higher than in our study. Notably, response was defined as 2 or more consecutive platelet counts ≥50 × 109/L (≥1 day apart) within 8 weeks of the first CM313 dose. Sustained response was defined as maintenance of a continuous platelet count ≥30 × 109/L, with at least a twofold increase from baseline, maintained over the 24-week period. Differences in study populations and end point definitions may have contributed to the varying response rates between this study and ours. Structural differences between the medicaments may also play a role, although knowledge of the structure of CM313 remains limited beyond its distinct complementarity-determining region sequence, which differs from that of daratumumab.25

A previous noninferiority study comparing IV daratumumab at dose 16 mg/kg and subcutaneous daratumumab at fixed dose of 1800 mg in patients with multiple myeloma, showed slower increase in plasma concentrations with a lower peak level in the subcutaneous group.26 However, a maximum trough concentration (Ctrough) of the drug was overall higher or similar for subcutaneous daratumumab in an overall study population. Of interest, patients ≤65 kg had 60% higher, whereas patients >85 kg had 12% lower values of maximum Ctrough with subcutaneous daratumumab than IV daratumumab. As such, these could potentially contribute to the observed differences between the 2 study populations.26

The IRR rate was numerically higher among the patients treated with CM313 compared with our study (32% vs 14%), which may be dependent of route of administration, as previously shown for daratumumab.26

Mezagitamab is another subcutaneous CD38 antibody that has been recently evaluated in a phase 2 trial with promising preliminary results, with a 91% platelet response defined as 2 platelet counts >50 × 109/L and ≥20 × 109/L above baseline on ≥2 visits.27

Although most patients in our study exhibited a rapid initial platelet rise, the primary end point response rate was evaluated at least 4 weeks after the daratumumab injection, and was 48%, suggesting that early increases may reflect corticosteroid premedication effects, or a synergistic effect with daratumumab.

Response and relapse rates did not appear to correlate with the number of subcutaneous daratumumab injections, with even distribution between the groups. Furthermore, in the safety run-in, 2 of 3 patients responded after only 4 injections of daratumumab. The small number of patients in each cohort precludes any definite conclusion regarding the optimal dosing; however, our results suggest that 4 doses may be as effective as 8 or 10 doses with regard to rate and duration of response.

All responding patients in our study were able to discontinue concomitant medications. This indicates that response to daratumumab is largely if not solely related to the drug, and is independent of other medications. This effect, if confirmed, may translate into a big advantage to the patient and health care system.

Daratumumab treatment consistently resulted in substantial decreases in CD38+ cells in peripheral blood and bone marrow, with a reduction of 90% in all assessments, and a decline in IgG levels albeit unrelated to platelet responses. There was no apparent difference in antiplatelet autoantibody positivity between responders and nonresponders. The findings may suggest that part of the response mechanisms involves modulation of CD38+ immune cells other than plasma cells, such as natural killer cells or T cells, and that the heterogeneity of pathophysiology means that not all patients will respond to any single therapeutic approach.28-30

Fatigue and impaired HRQoL are well-known manifestations of ITP. In the current study, HRQoL measured by SF-36 improved across all dimensions in responding patients. In 4 dimensions, the improvement was higher than the MID. There were also trends to improvement in general fatigue (domain 1 in MFI-20 score) in responders compared with nonresponders.

Daratumumab has been in clinical use for multiple myeloma for years, and is commercially available. Importantly, this means that the safety profile is well established, and the drug is usually well tolerated even in elderly frail patients. Of note, we did not observe any additional side-effects specific to the ITP population.

We followed all patients not requiring other types of ITP treatment until the end of the study, with the longest follow-up being almost 35 months. This provides valuable insight into the durability of response to daratumumab, and demonstrates the potential to induce treatment-free remissions.

Our study has several limitations, including a limited number of patients and the nonrandomized design. However, at the time our study was initiated, limited data existed on the use of CD38 antibodies in ITP, and therefore the study was intended as a hypothesis-generating study that aimed to assess the safety of daratumumab and explore potential efficacy signals. We also chose to use a dosage and schedule based on multiple myeloma regimens, while the optimal schedule for ITP may be different and should be explored in future studies. The investigated difference in cumulative dose between our cohorts was probably too small to have a major impact on outcomes and response durability. Finally we cannot exclude that the administration of corticosteroids as a premedication may have augmented the response rates during the study drug administration period. To minimize this potential effect, we measured the primary end point 4 weeks after the last injection and thus last (single) steroid dose.

This phase 2 study demonstrates the safety and efficacy of CD38 antibody daratumumab in patients with ITP who were heavily pretreated. Together with other recent anti-CD38 trials, these findings highlight the therapeutic potential of CD38-targeted approach in ITP. The consistent, durable responses, and favorable safety profile suggest that daratumumab would have utility beyond the refractory setting. Its use earlier in the disease course, either as monotherapy or in combination with corticosteroids or other agents, warrants exploration, particularly given the potential for synergistic effects and reduced reliance on prolonged immunosuppression. Early intervention may also modify the disease trajectory in select patients, leading to more sustained remissions. However, prospective, controlled trial is essential to confirm the findings in our study, optimize treatment strategies, and assess the role of re-treatment in relapsed responders.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who participated in the trial, and their caregivers, trial investigators, and safety monitoring board. The Norwegian National Unit for Platelet Immunology performed platelet autoantibody testing. Daratumumab was provided free of charge by Janssen Pharmaceutica NV (Beerse, Belgium).

This trial was sponsored and overseen by South-East Regional Health Authority, Østfold Hospital Trust (grant number 2020099), Research Council of Norway, Stiftelsen KG Jebsen, and Østfold Hospital, Norway.

The funders of this study had no role in study design, data collection, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Authorship

Contribution: G.T. and W.G. conceived and designed the trial with input from all the coauthors, coordinated the study, recruited patients, and participated in data analysis; G.T. wrote the statistical analysis plan, wrote the first draft of the manuscript with subsequent input from the coauthors, was responsible for statistical analysis, and analyzed data (which were collected by investigators) with input from the coauthors; P.A.H., H.T.T.T., H.F., E.T., M. Mahévas, and M. Michel screened, recruited, and followed patients; L.A.M., E.D., and H.K. performed and interpreted flow analyses of CD38+ cells; I.H.S. and M.T.A. supervised and interpreted monoclonal antibody immobilization of platelet antigens assay analysis; J.B., D.J.K., and T.H.A.T. participated in designing of the study and drafting of the study protocol; all authors and Janssen Pharmaceutica NV (Beerse, Belgium) reviewed, revised, and approved the manuscript before it was submitted to publication; all authors were involved in drafting the manuscript, had access to trial data, and were responsible for the decision to submit for publication.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: G.T. received lecture honoraria from and was part of the advisory board for Janssen, Sanofi, Sobi, and Grifols. P.A.H. received research funding from Bayer, Biogen, Commonwealth Serum Laboratories (CSL), and Sobi; and speaker honorarium from Bayer, BioMarin, CSL, Novo Nordisk, Octapharma, Pfizer, Roche, Takeda, and Sobi. H.T.T.T. received consultancy fees from and participated in advisory boards for AbbVie, Grifols, Novartis, and AstraZeneca. H.F. received research funding from Sanofi, Novartis, and Alexion. E.T. participated in advisory boards for Janssen, Sobi, Grifols, Novartis, Alexion, GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals (GSK), BeiGene, and AOP Orphan Pharmaceuticals. L.A.M. received grants from South East Regional Authority, Research Council of Norway, and Stiftelsen KG Jebsen. M. Mahévas received speaker’s and/or advisory fees from Novartis, Grifols, Incyte, and Amgen; and grant from GSK. M. Michel received speaker’s and/or advisory fees from Amgen, Grifols, Novartis, Sanofi, and Sobi. J.B. declares participation in consulting/advisory boards for Novartis, Janssen, Union Chimiqie Belge (UCB), Argenx, Alpine, RallyBio, and Pfizer. D.J.K. received research grants from Alnylam, Fulcrum, Hutchmed, Novartis, Principia, Sanofi, and Takeda; and consulting fees from Alexion, Alpine, Amgen, Argenx, BioCryst, Blackstone, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Cardurion, Caremark, Chugai, Hengrui, Hutchmed, Iconic Bio, Immunovant, Kaigen, Lilly, Medscape, Merck Sharp Dohme, New York Blood Center, Nexcella, Novartis, Nurix, Nuvig, Ouro, PeerView, Physicians Education Resource (PER), Pfizer, Platelet Disorder Support Association, Principia, Regeneron, Rigel, Sanofi, Seismic, Sobi, Takeda, Timberlyne, UCB, UpToDate, and Verve. T.H.A.T. received lecture honoraria and fees for participation in advisory boards from Sanofi, Takeda, and Janssen. W.G. received fees for participation in advisory boards from Amgen, Novartis, Pfizer, Principia Biopharma Inc (a Sanofi Company), Sanofi, Sobi, Grifols, UCB, Argenx, Cellphire, Alpine, Kedrion, HiBio, Hutchmed, and Takeda; lecture honoraria from Amgen, Novartis, Pfizer, BMS, Sobi, Grifols, Sanofi, and Bayer; and research grants from Bayer, BMS/Pfizer, UCB, Sobi, and Sanofi. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Galina Tsykunova, Division of Medicine, Department of Hematology, Haukeland University Hospital, Haukelandsveien 22, 5009 Bergen, Norway; email: galina.tsykunova@helse-bergen.no.

References

Author notes

The study schedule and preliminary results of the safety run-in phase were presented as a poster presentation at the 63rd annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Atlanta, GA, 11 to 14 December 2021. Short-term response and safety results were presented as an oral presentation at the 30th annual congress of the European Hematology Assosiation, Milan, Italy, 12 to 15 June 2025. Short-and long-term safety and efficacy results were presented as an oral presentation at the 33rd annual congress of the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, Washington, DC, 21 to 25 June 2025.

Data requests will be reviewed on a case-by-case basis by the corresponding and last authors. Such requests should be sent along with the research proposal for consideration. Data are not publicly available due to restrictions, such as containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants. The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan are provided in the supplemental Appendix.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.