Key Points

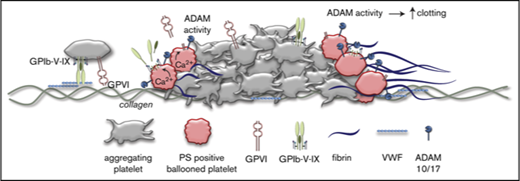

Specific populations of activated platelets shed GPIbα and GPVI by ADAM activity via pathways related to, but not secondary to, PS exposure.

ADAM-mediated glycoprotein shedding increases coagulation factor binding and enhances platelet-dependent fibrin formation.

Abstract

The platelet receptors glycoprotein Ibα (GPIbα) and GPVI are known to be cleaved by members of a disintegrin and metalloprotease (ADAM) family (ADAM10 and ADAM17), but the mechanisms and consequences of this shedding are not well understood. Our results revealed that (1) glycoprotein shedding is confined to distinct platelet populations showing near-complete shedding, (2) the heterogeneity between (non)shed platelets is independent of agonist type but coincides with exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS), and (3) distinct pathways of shedding are induced by elevated Ca2+, low Ca2+ protein kinase C (PKC), or apoptotic activation. Furthermore, we found that receptor shedding reduces binding of von Willebrand factor, enhances binding of coagulation factors, and augments fibrin formation. In response to Ca2+-increasing agents, shedding of GPIbα was abolished by ADAM10/17 inhibition but not by blockage of calpain. Stimulation of PKC induced shedding of only GPIbα, which was annulled by kinase inhibition. The proapoptotic agent ABT-737 induced shedding, which was caspase dependent. In Scott syndrome platelets that are deficient in Ca2+-dependent PS exposure, shedding occurred normally, indicating that PS exposure is not a prerequisite for ADAM activity. In whole-blood thrombus formation, ADAM-dependent glycoprotein shedding enhanced thrombin generation and fibrin formation. Together, these findings indicate that 2 major activation pathways can evoke ADAM-mediated glycoprotein shedding in distinct platelet populations and that shedding modulates platelet function from less adhesive to more procoagulant.

Introduction

In hemostasis and thrombosis, blood platelets are triggered to adhere to an injured or atherosclerotic vessel wall. Platelet adhesion and subsequent aggregate formation are controlled, in a synergistic way, by multiple glycoprotein receptors.1-3 Two crucial receptors are glycoprotein VI (GPVI), which interacts with collagen and fibrin, and GPIb-V-IX, which binds to von Willebrand factor (VWF). Other receptors with high adhesive strength are CLEC-2 with unknown ligands in the healthy vessel wall; integrin α6β1, which binds laminin; integrin αIIbβ3, which, for example, binds fibrinogen; and integrin α2β1, which also interacts with collagen.4 Research has indicated that, following activation of the platelets, most, and perhaps all, of these adhesive receptors can be inactivated, suggesting the presence of postactivation mechanisms to control platelet interactions with their environment. An example are platelets with high cytosolic Ca2+ levels and phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure, which undergo calpain-dependent cleavage of the intracellular integrin β3 chain and adjacent signaling proteins, resulting in the inactivation of αIIbβ3.5,6 Another example is cleavage of the extracellular domains of GPIbα and GPVI following platelet stimulation. Studies with inhibitors and murine knockouts have indicated that the latter cleavage is mediated by 2 members of a disintegrin and metalloprotease (ADAM) family. It is considered that GPIbα is primarily cleaved by ADAM17, whereas GPVI shedding is predominantly controlled by ADAM10.7-10 However, murine studies have indicated significant substrate redundancy between the 2 ADAM isoforms.11

The literature indicates that ADAM-mediated shedding of the extracellular domains of GPIbα and GPVI can be induced by a variety of platelet-stimulating agents. These include collagen, thrombin, the protein kinase C (PKC) stimulus phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), mitochondrial-uncoupling compounds, and apoptosis-inducing agents.7,9,11-13 In addition, there is evidence that shedding of GPIbα can be induced at high wall shear rates or by platelet storage.14,15 It remains unknown which signaling pathways cause platelets to shed particular glycoproteins. A first concept, using the compound W7, suggested that platelet ADAM activity and shedding are negatively regulated by the Ca2+-dependent protein kinase cofactor calmodulin.8,9 Other reports propose that reactive oxygen species produced in the platelet mitochondria induce ADAM activation and, hence, receptor shedding.12,16,17 In lymphocytes, receptor shedding has been related to phospholipid scrambling and PS exposure, which are key processes in apoptosis.18 Together, this suggests the existence of several mechanisms of ADAM-dependent receptor shedding, likely with consequences for platelet function.

We hypothesized that 4 distinct pathways can contribute to ADAM-dependent shedding of GPIbα and GPVI: Ca2+ elevation, PKC activation, PS exposure, and caspase activity. Based on this, we used a broad range of potential shedding-inducing agents and inhibitors to study the involvement of these pathways in specific populations of activated platelets. Our results indicate that shedding is regulated on a single-platelet level primarily via Ca2+- or caspase-dependent pathways that are accompanied by, but not caused by, PS exposure. Furthermore, we examined the consequences of glycoprotein shedding for platelet functional properties.

Materials and methods

Materials

Materials and additional methods are available in the supplemental Materials and methods.

Blood collection and platelet preparation

Human blood was obtained from healthy volunteers and a patient with Scott syndrome after informed consent, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, under protocols reviewed by the local ethics committee. The Scott syndrome patient was genotyped as compound heterozygous in ANO6 with 1 mutation, IVS6 + 1G→A, resulting in exon 6 skipping, and a second mutation (c.1219insT) causing a premature stop in translation.19

Blood was collected into 3.2% citrate for flow perfusion studies or into acid-citrate dextrose (1:6 ACD, 80 mM trisodium citrate, 52 mM citric acid, and 180 mM glucose) for platelet isolation. The first 3 mL of blood was discarded. Washed platelets were prepared as described before.20 Platelet count was determined with a Sysmex XP-300 thrombocounter (Sysmex, Chuo-ku Kobe, Japan).

Flow cytometry

Populations of washed platelets (1 × 108/mL) stimulated with (combinations of) ABT-737 (10 µM), ionomycin (10 µM), convulxin (100 ng/mL), CRP-XL (5 µg/mL), thrombin (4 nM), SFLLRN (15 µM), factor Xa (10 μg/mL), 2MeS-ADP (10 µM), CCCP (100 µM), or PMA (100 nM) were analyzed with an Accuri C6 flow cytometer and software, as described in detail in supplemental Materials and methods. Surface expression of GPIbα, GPVI, or GPIX was measured after labeling with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) anti-GPIbα monoclonal antibody (mAb), phycoerythrin (PE) anti-GPVI mAb, or FITC anti-GPIX mAb, respectively; AF647-annexin A5 was added to measure PS exposure. Binding of VWF, OG488-prothrombin, OG488-factor Xa, or AF488-factor Va was essentially as described.21

Whole-blood thrombus formation with platelet activation

Blood was perfused over microspots of collagen type I under coagulant conditions, as detailed in the supplemental Materials and methods. Stabilized activated thrombi were stained as indicated for GPIbα (FITC mAb, 2 µg/mL), GPVI (PE mAb, 1 µg/mL), and/or PS exposure (AF647 annexin A5, 5 µg/mL). Alternatively, platelet thrombi formed on collagen were used as substrate for thrombin-generation measurements, as described.22

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed with a paired-sample Student t test. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 23 package (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

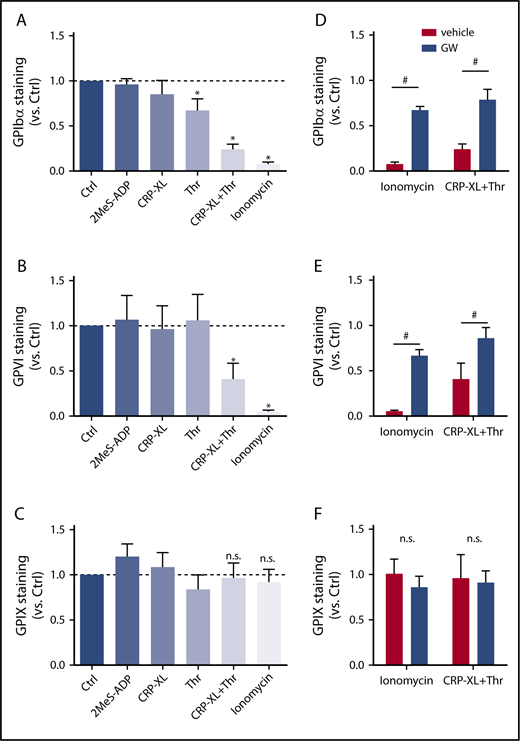

Strong platelet stimulation required for shedding of GPIbα and GPVI

To systematically study the roles of various signaling pathways implicated in GPIbα and GPVI shedding, washed human platelets were stimulated with a variety of agonists at near-maximal concentrations and then quantified for staining for the extracellular domains of GPIbα and GPVI using flow cytometry. To check for possible internalization of the GPIb-V-IX complex, staining for GPIX was used as a control, because this glycoprotein chain is not cleaved by ADAM10/17.23 Although platelet stimulation with stable ADP (2MeS-ADP) did not alter the staining for GPIbα, stimulation with CRP-XL (GPVI receptor agonist) or thrombin (PAR1/4 agonist) led to a modest reduction (Figure 1A). No reduced staining for GPVI was observed under these conditions (Figure 1B). For the whole-platelet population, costimulation with CRP-XL plus thrombin led to a substantial (60% to 80%) reduction in GPIbα and GPVI staining. This reduction was even more pronounced (>90%) upon stimulation with the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin (Figure 1A-B). None of these stimuli affected the staining for GPIX (Figure 1C), thus excluding interference of internalization of the GPIb-V-IX complex. Importantly, pretreatment of platelets with the ADAM10/17 inhibitor GW280264X24,25 essentially abrogated the loss of GPIbα and GPVI staining in platelets stimulated with CRP-XL/thrombin or ionomycin (Figure 1D-F), thus confirming the involvement of ADAM extracellular proteases. Other ADAM inhibitors, including GI254023X (specificity ADAM10 > ADAM17) and TAPI (ADAM17 > ADAM10), had similar effects (data not shown).

ADAM10/17-mediated glycoprotein shedding upon platelet stimulation with strong agonists. Washed platelets, which were preincubated for 15 minutes with DMSO (vehicle) or ADAM17/10 inhibitor GW280264X (GW; 5 μM), were stimulated with 2MeS-ADP, CRP-XL, thrombin (Thr), or CRP-XL/Thr (GPIbα, n = 8) for 180 minutes or with ionomycin (GPIbα, n = 8) for 60 minutes (all at 37°C). Unstimulated platelets were used as control (Ctrl). Staining for GPIbα (A,D), GPVI (B,E), and GPIX (C,F) was measured with optimized concentrations of FITC anti-GPIbα mAb, PE anti-GPVI mAb, or FITC anti-GPIX mAb using flow cytometry (mean fluorescence intensities). (A-C) Effect of agonist stimulation on glycoprotein expression levels. Data are normalized to those of unstimulated platelets. (D-F) Effect of GW treatment on glycoprotein expression level. Data are mean ± SD, n = 3-5 (≥3 donors). *P < .05 vs unstimulated platelets, #P < .05 vs vehicle. n.s., not significant.

ADAM10/17-mediated glycoprotein shedding upon platelet stimulation with strong agonists. Washed platelets, which were preincubated for 15 minutes with DMSO (vehicle) or ADAM17/10 inhibitor GW280264X (GW; 5 μM), were stimulated with 2MeS-ADP, CRP-XL, thrombin (Thr), or CRP-XL/Thr (GPIbα, n = 8) for 180 minutes or with ionomycin (GPIbα, n = 8) for 60 minutes (all at 37°C). Unstimulated platelets were used as control (Ctrl). Staining for GPIbα (A,D), GPVI (B,E), and GPIX (C,F) was measured with optimized concentrations of FITC anti-GPIbα mAb, PE anti-GPVI mAb, or FITC anti-GPIX mAb using flow cytometry (mean fluorescence intensities). (A-C) Effect of agonist stimulation on glycoprotein expression levels. Data are normalized to those of unstimulated platelets. (D-F) Effect of GW treatment on glycoprotein expression level. Data are mean ± SD, n = 3-5 (≥3 donors). *P < .05 vs unstimulated platelets, #P < .05 vs vehicle. n.s., not significant.

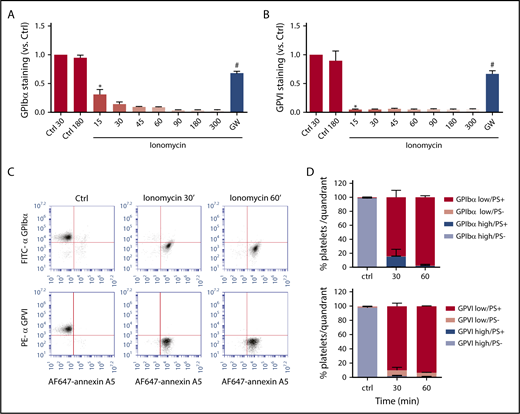

Population of platelets with PS exposure, accompanied by GPIbα and GPVI shedding

Flow cytometry was also used to assess the kinetics of loss of surface glycoproteins (inhibitable by GW280264X), as a measure of receptor shedding, in platelets stimulated with the most active inducer, ionomycin. For all platelets, 90% of detectable GPIbα was lost after 30 minutes of stimulation, whereas 90% of detectable GPVI had already disappeared after 15 minutes (Figure 2A-B). This kinetic difference may be due to the higher copy number of GPIbα in comparison with GPVI expressed per platelet, estimated as 18 800 and 9600 copies, respectively.26 Stimulation of platelets with ionomycin is known to result in phospholipid scrambling and surface exposure of PS.27 Considering that membrane destabilization may trigger ADAM activity, we performed dual staining of platelets for PS exposure (AF-647 annexin A5) and either GPIbα (FITC mAb) or GPVI (PE mAb) expression. Flow cytometric dot plots confirmed that the PS-exposing platelets were low in GPIbα and GPVI staining (Figure 2C), although the staining, especially for GPIbα, continued to decrease after full PS exposure (Figure 2D). Pretreatment of platelets with the ADAM10/17 inhibitor GW280264X blocked GPIbα and GPVI expression changes (Figure 2A-B).

Comparable kinetics of glycoprotein receptor shedding and PS exposure in ionomycin-stimulated platelets. Washed platelets, which were preincubated with vehicle or GW280264X (GW; 5 μM), were left unstimulated (Ctrl) or were stimulated for the indicated times (15 to 300 minutes) with ionomycin (37°C) and evaluated for glycoprotein expression by flow cytometry. (A-B) ADAM-dependent decrease in surface expression of GPIbα and GPVI over time. Mean fluorescence intensities were normalized to those of unstimulated platelets. (C-D) Analysis of platelet populations after dual staining for GPIbα (FITC mAb) or GPVI (PE mAb) and for PS exposure (AF647-annexin A5). Flow cytometric events were separated into 4 platelet populations: GPIbα/VIhigh PS−, GPIbα/VIhigh PS+, GPIbα/VIlow PS−, and GPIbα/VIlow PS+. Shown are representative dot plots and quantification of 4 quadrants. Data are mean ± SD, n = 3-5 (≥3 donors). *P < .05 vs control, #P < .05 vs vehicle.

Comparable kinetics of glycoprotein receptor shedding and PS exposure in ionomycin-stimulated platelets. Washed platelets, which were preincubated with vehicle or GW280264X (GW; 5 μM), were left unstimulated (Ctrl) or were stimulated for the indicated times (15 to 300 minutes) with ionomycin (37°C) and evaluated for glycoprotein expression by flow cytometry. (A-B) ADAM-dependent decrease in surface expression of GPIbα and GPVI over time. Mean fluorescence intensities were normalized to those of unstimulated platelets. (C-D) Analysis of platelet populations after dual staining for GPIbα (FITC mAb) or GPVI (PE mAb) and for PS exposure (AF647-annexin A5). Flow cytometric events were separated into 4 platelet populations: GPIbα/VIhigh PS−, GPIbα/VIhigh PS+, GPIbα/VIlow PS−, and GPIbα/VIlow PS+. Shown are representative dot plots and quantification of 4 quadrants. Data are mean ± SD, n = 3-5 (≥3 donors). *P < .05 vs control, #P < .05 vs vehicle.

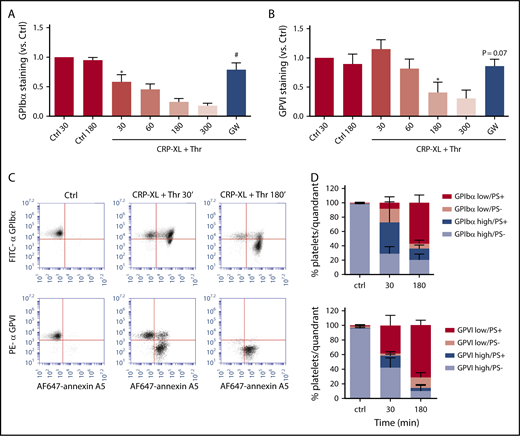

Similar analysis was performed for platelets stimulated with CRP-XL plus thrombin. These agonists, in comparison with ionomycin, caused a slower loss of surface-expressed GPIbα and GPVI, which continued for ≥3 hours. This fluorescence decrease again was antagonized by GW280264X (Figure 3A-B). Dual-labeling analysis indicated that the population of PS-exposing platelets appeared before the reduction in staining for GPIbα or GPVI (Figure 3C). Quantification of the platelets with(out) PS exposure and shed/unshed receptors indicated that, at an intermediate time of 30 minutes, a considerable fraction of platelets (16% to 44%) with PS exposure still showed appreciable staining for GPIbα and GPVI (Figure 3D). These results are compatible with the suggestion that platelet exposure to PS is a prerequisite for ADAM-mediated receptor shedding, such as reported for lymphocytes.18 However, both processes could also occur independently in platelets that have sensed a certain signal, such as high Ca2+.

Glycoprotein receptor shedding following PS exposure in CRP-XL/thrombin–stimulated platelets. Washed platelets, which were preincubated with vehicle or ADAM10/17 inhibitor GW280264X (GW; 5 μM), were left unstimulated (Ctrl) or were stimulated with CRP-XL plus thrombin (Thr) for the indicated times and then evaluated for glycoprotein expression by flow cytometry. (A-B) ADAM-dependent decrease in surface expression of GPIbα and GPVI over time. (C-D) Population analysis of platelets after dual staining for GPIbα (FITC mAb) or GPVI (PE mAb) and for PS exposure (AF647-annexin A5). Four platelet populations are defined, as in Figure 2. Note the gradual increase in the PS-exposing platelet populations and the slower increase in populations with shed GPIbα or GPVI. Data are mean ± SD, n = 3-7 (≥3 donors). *P < .05 vs control, #P < .05 vs vehicle.

Glycoprotein receptor shedding following PS exposure in CRP-XL/thrombin–stimulated platelets. Washed platelets, which were preincubated with vehicle or ADAM10/17 inhibitor GW280264X (GW; 5 μM), were left unstimulated (Ctrl) or were stimulated with CRP-XL plus thrombin (Thr) for the indicated times and then evaluated for glycoprotein expression by flow cytometry. (A-B) ADAM-dependent decrease in surface expression of GPIbα and GPVI over time. (C-D) Population analysis of platelets after dual staining for GPIbα (FITC mAb) or GPVI (PE mAb) and for PS exposure (AF647-annexin A5). Four platelet populations are defined, as in Figure 2. Note the gradual increase in the PS-exposing platelet populations and the slower increase in populations with shed GPIbα or GPVI. Data are mean ± SD, n = 3-7 (≥3 donors). *P < .05 vs control, #P < .05 vs vehicle.

Glycoprotein shedding can also be evoked by other platelet-activating agents independently of receptor stimulation. These include the proapoptotic BH3 mimetic ABT-737,13 also inducing PS exposure28 ; the PKC activator PMA7,29 ; and the mitochondrial-uncoupling agent CCCP7 ; the latter two act in an essentially Ca2+-independent way.30,31 Treatment of platelets with ABT-737 resulted in a gradual (GW280264X-inhibitable) loss of GPIbα and GPVI expression, needing >60 minutes for completion (supplemental Figure 1A-B). Dual labeling with anti-GPIbα mAb and AF647-annexin A5 indicated that GPIbα shedding, at least in part, preceded PS exposure, whereas GPVI shedding was markedly slower than PS exposure (supplemental Figure 2A-B). Ultimately, a population of PS-exposing platelets was formed that had completely lost their glycoproteins.

To exclude microparticle formation as a cause of the loss of glycoproteins, scatter profiles were determined in the presence of MegaMix calibration beads. Quantification revealed that the majority of flow cytometric events (resting, 99.8%; ionomycin, 90.8%) were comparable in size or had greater forward scatter than the 0.9-µm beads (supplemental Figure 3). It is noted that the ionomycin-stimulated cells assume a ballooning morphology, which increases their size, but also makes them more translucent,32 with likely lower scatter properties. Furthermore, scatter profiles, in contrast to glycoprotein levels, were not altered by ADAM inhibition with GW280264X (supplemental Figure 4).

For the whole-platelet population, stimulation with PMA resulted in only limited GPIbα shedding, which remained incomplete after 5 hours, whereas GPVI was not shed at all (supplemental Figure 1C-D). Double labeling indicated that those platelets that had shed GPIbα were PS negative (supplemental Figure 2C-D). Platelet treatment with CCCP caused even slower shedding, especially of GPVI, requiring up to 5 hours to become measurable (supplemental Figure 1E-F). Also with CCCP, limited PS exposure was measured. Together, these data indicated that agonist-induced glycoprotein receptor shedding and PS exposure occur in the same platelet population, although the different kinetics indicate that the processes occur independently.

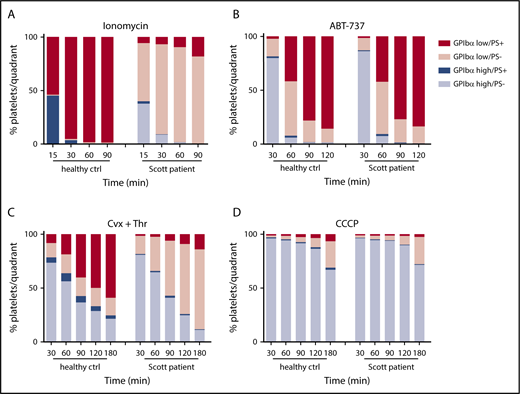

To investigate the relationship between PS exposure and shedding in more detail, platelets were examined from a Scott syndrome patient, which aggregate normally but are deficient in PS exposure when stimulated with Ca2+-mobilizing agonists, such as ionomycin or CRP-XL/thrombin.28,32 Strikingly, the Scott syndrome platelets, regardless of the stimulus applied (ionomycin, ABT-737, convulxin/thrombin, or CCCP), displayed high GPIbα shedding similarly to platelets from a control donor (Figure 4). Earlier, we established that these Scott syndrome platelets show normal agonist-induced Ca2+ fluxes.33 Hence, our data suggest that glycoprotein shedding and PS exposure are Ca2+-dependent events but are not mutually dependent.

Normal glycoprotein shedding in Scott syndrome platelets with defective PS exposure. Platelets from a healthy control subject or a Scott patient were stimulated with 10 µM ionomycin (A), 10 µM ABT-737 (B), 100 ng/mL convulxin and 4 nM thrombin (C), or 100 µM CCCP (D) at 37°C. GPIbα expression and PS exposure were measured at the indicated time points. Platelets were separated into 4 populations (GPIbαhigh PS−, GPIbαhigh PS+, GPIbαlow PS−, and GPIbαlow PS+) and quantified. Data are means of 3 replicates.

Normal glycoprotein shedding in Scott syndrome platelets with defective PS exposure. Platelets from a healthy control subject or a Scott patient were stimulated with 10 µM ionomycin (A), 10 µM ABT-737 (B), 100 ng/mL convulxin and 4 nM thrombin (C), or 100 µM CCCP (D) at 37°C. GPIbα expression and PS exposure were measured at the indicated time points. Platelets were separated into 4 populations (GPIbαhigh PS−, GPIbαhigh PS+, GPIbαlow PS−, and GPIbαlow PS+) and quantified. Data are means of 3 replicates.

Pathways of glycoprotein shedding: key roles of calcium increase and caspase activity

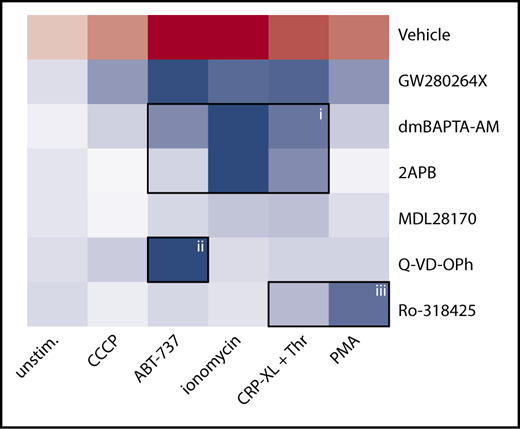

To define the main signaling pathways accountable for receptor shedding in response to different agents (ionomycin, CRP-XL/thrombin, ABT-737, PMA, or CCCP), a panel of inhibitors was applied to block specific pathways. Thus, platelets were pretreated with calpain inhibitor MDL-28170,5 pan-caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPh,28 general PKC inhibitor Ro-318425,34 chelator of cytosolic Ca2+ dm-BAPTA AM,28 or Ca2+ entry inhibitor 2APB.35 The combined effects of agonist and inhibitors (supplemental Table 1) were converted into a heat map, representing the relative agonist strength to induce GPIbα shedding (red) and the inhibitor efficacy to antagonize this response (blue) (Figure 5). This heat map identifies the following principal pathways for GPIbα shedding: (1) high Ca2+ (inhibited by dm-BAPTA AM, 2APB, or absence of extracellular CaCl2) in response to ionomycin > CRP-XL/thrombin > ABT-737, (2) low Ca2+ caspase activity (inhibited by Q-VD-OPh) for ABT-737, and (3) low Ca2+ PKC activation (inhibited by Ro-318425) for PMA > CRP-XL/thrombin. A minor involvement of calpain was noted for ionomycin-treated platelets.

Analysis of signaling pathways implicated in agonist-induced glycoprotein shedding. Washed platelets were pretreated with ADAM10/17 GW280264X, the calpain inhibitor MDL-28170, the pan-caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPh, the general PKC inhibitor Ro-318425, the Ca2+ chelator dm-BAPTA AM, or the Ca2+ entry inhibitor 2APB. Samples were stimulated with ionomycin/CaCl2, CRP-XL plus thrombin, PMA, ABT-737, or CCCP, as indicated. Data are normalized to those of unstimulated platelets without any inhibitors. Shown is a heat map representing the effects of agonists on GPIbα shedding (red), as well as relative antagonizing effects of inhibitors (blue). Note the 3 clusters representing a role for Ca2+ elevation (i), caspase activation (ii), and PKC activity (iii). See supplemental Table 1 for additional information.

Analysis of signaling pathways implicated in agonist-induced glycoprotein shedding. Washed platelets were pretreated with ADAM10/17 GW280264X, the calpain inhibitor MDL-28170, the pan-caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPh, the general PKC inhibitor Ro-318425, the Ca2+ chelator dm-BAPTA AM, or the Ca2+ entry inhibitor 2APB. Samples were stimulated with ionomycin/CaCl2, CRP-XL plus thrombin, PMA, ABT-737, or CCCP, as indicated. Data are normalized to those of unstimulated platelets without any inhibitors. Shown is a heat map representing the effects of agonists on GPIbα shedding (red), as well as relative antagonizing effects of inhibitors (blue). Note the 3 clusters representing a role for Ca2+ elevation (i), caspase activation (ii), and PKC activity (iii). See supplemental Table 1 for additional information.

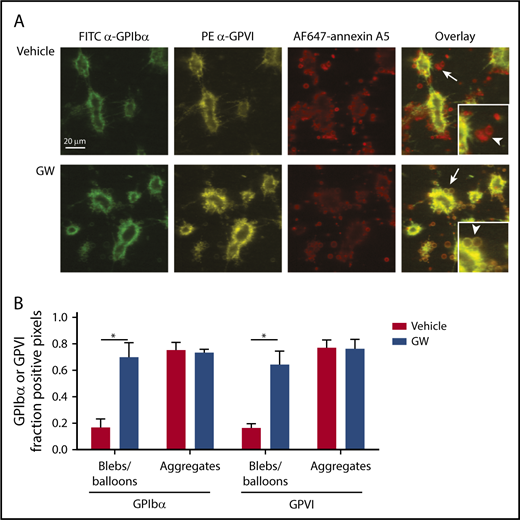

Heterogeneous shedding of GPIbα and GPVI in platelet thrombi

Because GPIbα and GPVI are key receptors in the regulation of collagen-dependent thrombus formation under flow,1,4 it was reasoned that ADAM-mediated cleavage of the glycoproteins may affect the adhesion of platelets to aggregates or thrombi. To examine this, platelet thrombi were allowed to form on collagen under coagulant conditions. In this setting, thrombi are known to consist of 2 populations of platelets: pseudopod-containing platelets in aggregates and patches of balloon-shaped PS-exposing platelets surrounding the aggregates.1,36 For the aggregated platelets, no difference was seen in staining for GPIbα or GPVI expression, even after 3 hours of incubation (Figure 6). In contrast, the balloon-shaped PS-exposing platelets no longer stained for GPIbα or GPVI and were loosely connected to the thrombi.

Selective loss of GPIbα and GPVI in high-Ca2+PS-exposing platelets in thrombi. Platelet thrombi were formed in flow chambers on collagen type I using whole-blood perfusion at a wall shear rate of 1000 s−1. The thrombi were postactivated with thrombin, incubated with vehicle or GW280264X (GW) for up to 180 minutes at 37°C, and stained for GPIbα and GPVI expression and PS exposure. (A) Representative confocal fluorescence images of GPIbα and GPVI expression and PS exposure. PS-exposing ballooned platelets are indicated by arrows and arrowheads. (B) Regions of interest corresponding to aggregated platelets and ballooned platelets were analyzed for fluorescence staining. Pixels representing GPIbα− or GPVI+ platelets were determined and expressed as percentages of surface area coverage of ballooned or aggregated platelets. Data are mean ± SD, n = 3. *P < .05.

Selective loss of GPIbα and GPVI in high-Ca2+PS-exposing platelets in thrombi. Platelet thrombi were formed in flow chambers on collagen type I using whole-blood perfusion at a wall shear rate of 1000 s−1. The thrombi were postactivated with thrombin, incubated with vehicle or GW280264X (GW) for up to 180 minutes at 37°C, and stained for GPIbα and GPVI expression and PS exposure. (A) Representative confocal fluorescence images of GPIbα and GPVI expression and PS exposure. PS-exposing ballooned platelets are indicated by arrows and arrowheads. (B) Regions of interest corresponding to aggregated platelets and ballooned platelets were analyzed for fluorescence staining. Pixels representing GPIbα− or GPVI+ platelets were determined and expressed as percentages of surface area coverage of ballooned or aggregated platelets. Data are mean ± SD, n = 3. *P < .05.

Incubation of thrombi in the presence of GW280264X retained the staining for GPIbα and GPVI of the balloon-shaped PS-exposing platelets. Exposure of PS was not affected by GW280264X treatment (9.4% ± 3.0% surface area coverage [SAC] vs 12.1% ± 6.8% SAC for controls, mean ± SD, n = 3, P = .39). When the thrombi on collagen were postactivated with ionomycin, the number of loosely adhered PS-exposing platelets markedly increased, whereas staining for GPIbα and GPVI decreased (supplemental Figure 5). Again, the latter decrease, in contrast to PS exposure, was antagonized by GW280264X. This confirmed the hypothesis that only the high-Ca2+ PS-exposing platelets in thrombi had lost their GPIbα and GPVI receptors via ADAM10/17-mediated shedding (ie, platelets with loose adherence to collagen or thrombi).

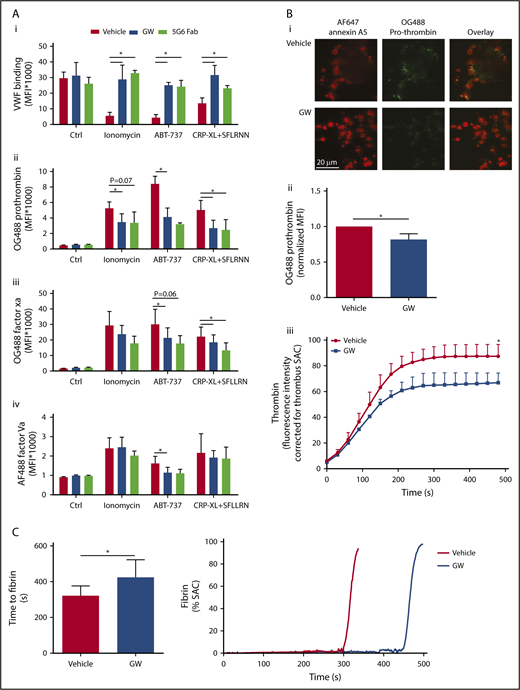

Functional effects of glycoprotein shedding

Additional studies were performed to determine the functional effects of GPIbα and GPVI shedding in the population of high-Ca2+ platelets. In addition to reducing platelet-adhesive properties, removal of the extracellular domain of these abundantly expressed glycoproteins may affect the binding properties of plasma proteins, such as coagulation factors. To investigate this, washed platelets were stimulated with ionomycin, ABT-737, or CRP-XL/SFLLRN (replacing thrombin, to prevent fibrin formation), which resulted in GPIbα and GPVI shedding, and were then evaluated for binding properties by flow cytometry. It appeared that all agonists reduced VWF binding (Figure 7Ai), a VWF receptor in accordance with the lower level of extracellular GPIbα. Notably, preincubation of platelets with GW280264X or the 5G6 Fab fragment, which blocks the ADAM17 cleavage site in GPIbα,10 almost completely restored VWF binding.

Glycoprotein shedding increases coagulation factor binding to platelets and enhances the formation of thrombin and fibrin. (A) Washed platelets were preincubated with vehicle, GW280264X (GW; 5 µM, 15 minutes), or 5G6 Fab fragment, which are known to block ADAM17-mediated shedding of GPIbα (10 µg/mL, 15 minutes). After 60 minutes of stimulation (37°C) with ionomycin, ABT-737, or CRP-XL plus SFLLRN, flow cytometry was used to measure platelet binding of VWF with fluorescent anti-VWF mAb (in the presence of ristocetin) (Ai), OG488-prothrombin (Aii), OG488-factor Xa (Aiii), or AF488-factor Va (Aiv). Binding of prothrombin, factor Xa, and factor Va was evaluated for the PS-exposing platelet population, identified with AF647-annexin A5. Data are mean ± SD, n = 3-6. (B) Platelet thrombi were formed on collagen and posttreated with SFLLRN for 60 minutes at 37°C in the presence of vehicle or GW (5 µM). After incubation, the thrombi were stained with OG488-prothrombin or were incubated with recalcified plasma supplemented with fluorogenic substrate Z-Gly-Gly-Arg-AMC to measure thrombin generation. Representative fluorescence images (Bi) and quantification of prothrombin fluorescence (Bii). (Biii) Time course (under stasis) of generation of thrombin from the surface of platelet thrombi formed in the presence or absence of GW. Data are mean ± SD, n = 3. (C) Kinetics of fibrin formation at a layer of adhered platelets on collagen, posttreated with ionomycin for 10 minutes, and inducing maximal shedding, in the presence of vehicle or GW. Fibrin formation was then allowed by perfusion of recalcified normal plasma at 250 s−1, while recording fluorescence images. Shown are times to fibrin formation and representative time traces of fibrin formation (expressed as SAC). Data are mean ± SD, n = 6. *P < .05.

Glycoprotein shedding increases coagulation factor binding to platelets and enhances the formation of thrombin and fibrin. (A) Washed platelets were preincubated with vehicle, GW280264X (GW; 5 µM, 15 minutes), or 5G6 Fab fragment, which are known to block ADAM17-mediated shedding of GPIbα (10 µg/mL, 15 minutes). After 60 minutes of stimulation (37°C) with ionomycin, ABT-737, or CRP-XL plus SFLLRN, flow cytometry was used to measure platelet binding of VWF with fluorescent anti-VWF mAb (in the presence of ristocetin) (Ai), OG488-prothrombin (Aii), OG488-factor Xa (Aiii), or AF488-factor Va (Aiv). Binding of prothrombin, factor Xa, and factor Va was evaluated for the PS-exposing platelet population, identified with AF647-annexin A5. Data are mean ± SD, n = 3-6. (B) Platelet thrombi were formed on collagen and posttreated with SFLLRN for 60 minutes at 37°C in the presence of vehicle or GW (5 µM). After incubation, the thrombi were stained with OG488-prothrombin or were incubated with recalcified plasma supplemented with fluorogenic substrate Z-Gly-Gly-Arg-AMC to measure thrombin generation. Representative fluorescence images (Bi) and quantification of prothrombin fluorescence (Bii). (Biii) Time course (under stasis) of generation of thrombin from the surface of platelet thrombi formed in the presence or absence of GW. Data are mean ± SD, n = 3. (C) Kinetics of fibrin formation at a layer of adhered platelets on collagen, posttreated with ionomycin for 10 minutes, and inducing maximal shedding, in the presence of vehicle or GW. Fibrin formation was then allowed by perfusion of recalcified normal plasma at 250 s−1, while recording fluorescence images. Shown are times to fibrin formation and representative time traces of fibrin formation (expressed as SAC). Data are mean ± SD, n = 6. *P < .05.

Considering the fact that PS-exposing platelets bind coagulation (co)factors of the prothrombinase complex,21 we assessed platelets, stimulated with ionomycin, ABT-737, or CRP-XL/SFLLRN, for binding of fluorescent-labeled prothrombin, factor Xa, and factor Va. As expected, the population of PS-exposing platelets showed strong staining for all these coagulation factors. Inhibition of ADAM activity with GW280264X resulted in a partial reduction in binding, which was significant for most of the agonists (Figure 7Aii-iii). Essentially similar results were obtained with 2 other ADAM inhibitors: GI254023X (specificity ADAM10 > ADAM17) and TAPI (ADAM17 > ADAM10) (supplemental Figure 6). Furthermore, the 5G6 Fab fragment, which inhibited GPIbα shedding, also had a suppressive effect on coagulation factor binding (Figure 7Aii-iii).

Evidence has been provided for a role of factor Xa in the shedding of GPVI but not GPIbα.37 To evaluate this in the present setting, platelets were treated with unlabeled factor Xa and then stimulated with thrombin and/or CRP-XL. However, no (enhancing) effect of factor Xa on GPIbα or GPVI staining could be determined (supplemental Figure 7).

Also in thrombi on collagen, PS-exposing platelets bind prothrombin.21 Using OG488-prothrombin, this was confirmed for thrombi posttreated with SFLLRN and incubated at 37°C to allow receptor shedding (Figure 7Bi-ii). Notably, ADAM inhibition with GW280264X lowered the prothrombin binding at (high-Ca2+) PS-exposing platelets, which is in line with the flow cytometry results. Again, annexin A5 staining was not affected by GW280264X. Staining for VWF revealed a lower level on PS-exposing platelets (data not shown), again in agreement with the requirement of noncleaved GPIbα for VWF binding.

To further assess whether the altered coagulation factor binding to platelets had functional consequences, kinetics of thrombin and fibrin was examined. Thrombi posttreated with SFLLRN, containing platelets with shed glycoproteins (incubation at 37°C), were perfused with recalcified plasma. Subsequent thrombin-generation measurements with the thrombin substrate Z-GGR-AMC indicated a gradual accumulation of thrombin activity, which was partly suppressed upon inhibition of receptor shedding by GW280264X (Figure 7Biii). Control experiments with plasma confirmed that this ADAM inhibitor, similar to other ADAM inhibitors, was without effect on the thrombin-generation process per se (data not shown). In addition, when collagen-adhered platelets with maximally shed receptors (by ionomycin stimulation) were superfused with recalcified plasma, fibrin formation was markedly delayed in the presence of GW280264X (Figure 7C). Taken together, these results indicated that the Ca2+-induced glycoprotein shedding of platelets is accompanied by a moderate increase in coagulation factor binding and enhanced thrombin and fibrin generation, which augment the platelet procoagulant phenotype.

Discussion

In this article, we provide new evidence for heterogeneity between populations of activated platelets with regard to the ADAM10/17-mediated shedding of extracellular GPIbα and GPVI. Flow cytometry revealed platelet populations with either near-complete glycoprotein shedding or without shedding, irrespective of the agonist used. The following shedding-promoting pathways were identified: (1) persistent Ca2+ increase (eg, induced by collagen/thrombin receptor stimulation or ionomycin), accompanied by, but not secondary, to PS exposure and ballooning; (2) low-Ca2+ PKC stimulation; and (3) caspase-mediated apoptosis, evoked by the BH3 mimetic ABT-737 and in this case preceding PS exposure. Our data further indicate that shedding of GPIbα was unaltered in platelets from a Scott syndrome patient, which are characterized by defective PS exposure but no other affected platelet responses.32,38 Although the populations of shed and PS-exposing platelets can overlap, we concluded that the major membrane disturbance upon PS exposure and balloon formation is not a prerequisite for ADAM-mediated proteolysis. Rather, it appears that both processes share a common denominator, such as elevated Ca2+, upstream in the regulatory pathways (supplemental Figure 8). Thus, our data with platelets deviate from a recent report on lymphocytes, in which PS exposure was considered to be upstream of ADAM17 activity.18

A surprising finding was that ADAM-induced glycoprotein shedding arises as an all-or-nothing event. This was concluded from the observations that shedding of the 2 glycoproteins, GPIbα (via ADAM17) and GPVI (via ADAM10), (1) occurs in the same population of platelets, regardless of the agonist type (with PMA as an exception, see later discussion), and (2) proceeds in single platelets to near completion, thus leading to a marked separation of populations with shed or nonshed receptors. The well-characterized ADAM10/17 inhibitor GW280264X almost completely inhibited this process, similar to the ADAM inhibitor GI254023X (5 µM, ∼80%), whereas common matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors were without effect (data not shown). One can speculate that residual protein cleavage can be due to other ADAM isoforms (eg, ADAM9, which is expressed at 600 copies per platelet).26

Previous investigations have shown that the isoforms ADAM10 and ADAM17 can cleave multiple platelet glycoproteins with at least partial redundancy.9 Yet, ADAM17 was found to preferentially cleave, similar to GPIbα, JAM-A, tetraspanin 9, and semaphorins, whereas ADAM10 preferentially shed GPVI and CD84.29,39 This substrate specificity might depend on the type of agonist, but this has not been clarified.11 In terms of the mechanism of ADAM-mediated glycoprotein shedding, other investigators have proposed an inhibitory role for calmodulin9 and a stimulating role for the p38 MAPK pathway,14 although the direct activation mechanism of the ADAM proteases in platelets is still unclear.40,41 Our data point to a positive, rather than a negative, role for elevated cytosolic Ca2+ in glycoprotein shedding, suggesting the involvement of a Ca2+-dependent protease activator.

In individual platelets, GPIbα and GPVI appeared to be cleaved to the same extent, independently of the type of agonist; PMA, which preferentially shed GPIbα, was a notable exception. The latter observation may imply a specific PKC-dependent activation pattern for ADAM17, with GPIbα as the preferred substrate. This suggestion is in line with observations from murine embryonic fibroblasts, showing that PKC activation does not activate ADAM10.42 Our data further point to a limited cross talk between the Ca2+-dependent and caspase-dependent activation pathways, because chelation of cytosolic Ca2+ resulted in only limited inhibition of shedding in apoptotic platelets. This is in line with earlier observations that ABT-737 primarily acts independently of Ca2+, although in a small platelet population it can cause increases in Ca2+.28 Shedding induced via PMA seems to be essentially Ca2+ independent, because PMA in platelets strongly suppresses agonist-induced increases in Ca2+.30,31

In thrombi formed ex vivo with aggregated and procoagulant platelets, ADAM-mediated glycoprotein shedding was also concentrated on ballooned platelets with PS exposure. This agrees with observations from other investigators that thrombi formed under flow conditions are high in ADAM10 activity.43 Furthermore, under conditions of shedding, regardless of agonist type, the binding of VWF to platelets decreased, whereas the binding of coagulation factors increased. Platelet PS exposure is known to be accompanied by less adhesion due to calpain-induced integrin cleavage.5 The present data add to this and indicate that such procoagulant platelets, with shed receptors, are defective in establishing GPIbα- and GPVI-dependent interactions (eg, to VWF, collagen, and fibrin).44-46 In addition, GPIbα provides a binding site for α-thrombin.47 However, this binding does not seem to play a role in the generation of thrombin and fibrin at PS-exposing platelets, given the rapid shedding of GPIbα from such platelets.

In terms of functional effects, our results point to a moderate enhancement of thrombin generation and fibrin formation under conditions of extensive glycoprotein shedding. Taken together, the present data indicate that (1) there is substantial heterogeneity in ADAM-induced glycoprotein shedding between activated platelets, and that (2) the platelet population with (near-complete) glycoprotein shedding has altered functional properties. Thus, the platelets undergoing ADAM-induced glycoprotein shedding seem to undergo a phenotypic change from less-adhesive platelets to more-procoagulant platelets. Although this study concentrated on GPIbα and GPVI, the broader substrate spectrum of platelet ADAM isoforms may suggest that the revealed changes are exemplary of a broader phenotypic change.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Netherlands Landsteiner Foundation for Blood Transfusion Research (1006) and the Cardiovascular Centre (HVC) of Maastricht University Medical Centre. F.S. was supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, M.M.P.C.D. was supported by the Netherlands Heart Foundation (Dr E. Dekker grant 2012T079), and P.E.B. was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant R01 HL071544).

Authorship

Contribution: C.C.F.M.J.B., F.S., T.M., T.G.M., and M.A.H.F. performed experiments and analyzed data; P.E.B., M.M.P.C.D., P.W.C., and R.L. contributed essential research tools; P.E.J.v.d.M. and J.W.M.H. designed and coordinated the research; C.C.F.M.J.B., P.E.J.v.d.M., and J.W.M.H. wrote the masnuscript; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Johan W. M. Heemskerk, Department of Biochemistry (CARIM), Maastricht University, P.O. Box 616, 6200 MD Maastricht, The Netherlands; e-mail: jwm.heemskerk@maastrichtuniversity.nl.