Abstract

Sickle-cell disease (SCD) leads to recurrent vaso-occlusive crises, chronic end-organ damage, and resultant physical, psychological, and social disabilities. Although hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) is potentially curative for SCD, this procedure is associated with well-recognized morbidity and mortality and thus is ideally offered only to patients at high risk of significant complications. However, it is difficult to identify patients at high risk before significant complications have occurred, and once patients experience significant organ damage, they are considered poor candidates for HSCT. In turn, patients who have experienced long-term organ toxicity from SCD such as renal or liver failure may be candidates for solid-organ transplantation (SOT); however, the transplanted organs are at risk of damage by the original disease. Thus, dual HSCT and organ transplantation could simultaneously replace the failing organ and eliminate the underlying disease process. Advances in HSCT conditioning such as reduced-intensity regimens and alternative donor selection may expand both the feasibility of and potential donor pool for transplantation. This review summarizes the current state of HSCT and organ transplantation in SCD and discusses future directions and the clinical feasibility of dual HSCT/SOT.

Introduction

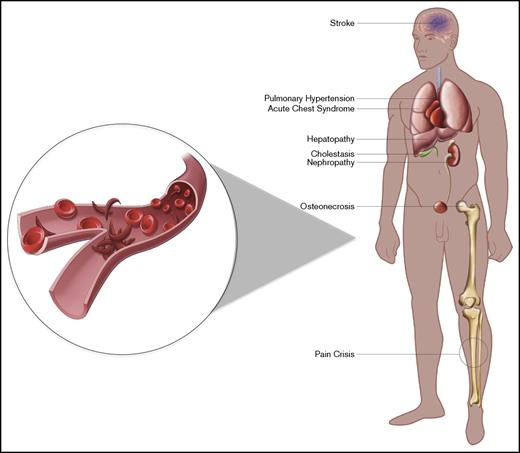

Sickle-cell disease (SCD) is the most common hemoglobinopathy worldwide. It affects ∼1 in 500 African American births, and approximately 100 000 Americans are estimated to have the disease.1 SCD is caused by a single nucleotide mutation in the β-globin gene that produces sickle hemoglobin (HbS), which has a propensity toward hemoglobin polymerization. Clinically, SCD is characterized by anemia, recurrent vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs), hemolysis, chronic organ dysfunction, and early mortality.2 The presentation and severity of the disease vary depending on the genotype; the homozygous state (HbSS) and the coinheritance of β-thalassemia gene with complete inactivity (HbSβ0 thalassemia) are typically associated with the most severe symptoms. In contrast, coinheritance of hemoglobin C (HbSC) or β-thalassemia with remaining synthesis of β chains (HbSβ+) leads to less severe manifestations.3 Wider use of newborn screening, early childhood education, penicillin prophylaxis, vaccination, blood transfusion, and hydroxyurea has improved childhood survival. The mortality rate among children is 0.5 per 100 000 persons. In contrast, the mortality rate in adults with SCD is >2.5 per 100 000 persons, and median life expectancy is 42 years of age for men and 48 years of age for women.4 Furthermore, a large prospective study revealed that 10-year survival probability dropped dramatically with age, especially after the age of 20 years, in patients with SCD compared with the general African American population, and 18% of deaths occurred in chronically ill patients with clinically evident organ failure.5 Chronic organ damage, caused by recurrent vascular obstruction, endothelial damage, and inflammation, includes nephropathy, hepatopathy, stroke, and chronic lung disease (Figure 1). At present, the only curative treatment for SCD is allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT). However, the decision to proceed with HSCT is complicated because of preexisting chronic organ damage as well as risk of transplantation-related complications. In contrast, solid-organ transplantation (SOT) can be considered for patients with SCD with organ failure, but end-organ transplantation for such patients is similarly challenging because the underlying SCD pathophysiology is not reversed and the transplanted organ is subject to the same risks of pathology from SCD. Ideally, one would be able to select only the patients at highest risk from their SCD.

Manifestations of SCD. The manifestations of SCD vary among patients. Patients may develop end-organ damage of the kidney, liver, and lungs, which would be potential targets for dual transplantation. Illustration by Evan Dailey, Rowan University.

Manifestations of SCD. The manifestations of SCD vary among patients. Patients may develop end-organ damage of the kidney, liver, and lungs, which would be potential targets for dual transplantation. Illustration by Evan Dailey, Rowan University.

HSCT in SCD

HSCT is in fact a successful form of gene therapy; transplantation replaces the genetically abnormal cells with hematopoietic cells that do not contain the sickle-cell mutation. In 1984, a child with SCD underwent HSCT for acute myeloid leukemia and was cured of SCD.6 This report established HSCT as a potentially curative therapy for SCD. Despite this, patients with SCD (particularly adults) seldom undergo HSCT because of donor availability, socioeconomic barriers, comorbidities from the disease, and concern for HSCT-related complications and mortality. According to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research, which has data from >75 centers across the United States, only 1089 patients with SCD underwent HSCT from 1991 to April 2017. Overall survival (OS) data were available in 1018 patients (773 patients age <16 years and 245 who were age ≥16 years). The OS rate at 1 year posttransplantation was 95% (95% confidence interval [CI], 94%-97%) in patients age <16 years and 87% (95% CI, 83%-91%) in patients age ≥16 years. Most transplantations were performed using HLA-identical sibling donors in both age groups (Table 1). Similar results have been obtained in several single-center studies (Table 2), most of which showed OS rates >90% with median follow-up of ≥1.8 years.

OS rates of patients by age from US centers who underwent allogeneic HSCT for SCD registered at CIBMTR

| . | HLA-identical sibling (n = 674) . | HLA-matched other relative (n = 25) . | HLA-mismatched relative (n = 101) . | Other relative (n = 5) . | Unrelated donor (n = 175) . | Cord blood (n = 109) . | All (N = 1089) . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | N evaluated . | OS (95% CI), % . | N evaluated . | OS (95% CI), %; or patients alive (%)* . | N evaluated . | OS (95% CI), % . | N evaluated . | Patients alive (%) . | N evaluated . | OS (95% CI), % . | N evaluated . | OS (95% CI), %; or patients alive (%)* . | N evaluated . | OS (95% CI), % . |

| Age <16 y | 500 | 17 | 41 | 3† | 120 | 92 | 773 | |||||||

| 100 d | 99 (98-100) | 88 (69-99) | 100 | 3 (100) | 94 (89-98) | 98 (94-100) | 98 (97-99) | |||||||

| 6 mo | 98 (97-99) | 88 (69-99) | 100 | 3 (100) | 91 (85-95) | 96 (90-99) | 96 (95-98) | |||||||

| 1 y | 97 (95-98) | 88 (69-99) | 97 (89-100) | 3 (100) | 89 (82-94) | 93 (87-98) | 95 (94-97) | |||||||

| 2 y | 95 (93-97) | 88 (69-99) | 90 (76-98) | 2 (67) | 85 (77-91) | 88 (81-94) | 92 (90-94) | |||||||

| Age ≥16 y | 139 | 6† | 50 | 2† | 47 | 13† | 257 | |||||||

| 100 d | 99 (96-100) | 6 (100) | 98 (92-100) | 2 (100) | 96 (88-100) | 10 (77) | 97 (94-99) | |||||||

| 6 mo | 96 (93-99) | 5 (83) | 94 (85-99) | 1 (50) | 89 (78-96) | 8 (62) | 93 (89-96) | |||||||

| 1 y | 92 (87-96) | 4 (66) | 89 (78-96) | 1 (50) | 76 (62-88) | 8 (62) | 87 (83-91) | |||||||

| 2 y | 87 (80-92) | 3 (50) | 86 (74-95) | 1 (50) | 64 (47-80) | 7 (53) | 82 (76-86) | |||||||

| . | HLA-identical sibling (n = 674) . | HLA-matched other relative (n = 25) . | HLA-mismatched relative (n = 101) . | Other relative (n = 5) . | Unrelated donor (n = 175) . | Cord blood (n = 109) . | All (N = 1089) . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | N evaluated . | OS (95% CI), % . | N evaluated . | OS (95% CI), %; or patients alive (%)* . | N evaluated . | OS (95% CI), % . | N evaluated . | Patients alive (%) . | N evaluated . | OS (95% CI), % . | N evaluated . | OS (95% CI), %; or patients alive (%)* . | N evaluated . | OS (95% CI), % . |

| Age <16 y | 500 | 17 | 41 | 3† | 120 | 92 | 773 | |||||||

| 100 d | 99 (98-100) | 88 (69-99) | 100 | 3 (100) | 94 (89-98) | 98 (94-100) | 98 (97-99) | |||||||

| 6 mo | 98 (97-99) | 88 (69-99) | 100 | 3 (100) | 91 (85-95) | 96 (90-99) | 96 (95-98) | |||||||

| 1 y | 97 (95-98) | 88 (69-99) | 97 (89-100) | 3 (100) | 89 (82-94) | 93 (87-98) | 95 (94-97) | |||||||

| 2 y | 95 (93-97) | 88 (69-99) | 90 (76-98) | 2 (67) | 85 (77-91) | 88 (81-94) | 92 (90-94) | |||||||

| Age ≥16 y | 139 | 6† | 50 | 2† | 47 | 13† | 257 | |||||||

| 100 d | 99 (96-100) | 6 (100) | 98 (92-100) | 2 (100) | 96 (88-100) | 10 (77) | 97 (94-99) | |||||||

| 6 mo | 96 (93-99) | 5 (83) | 94 (85-99) | 1 (50) | 89 (78-96) | 8 (62) | 93 (89-96) | |||||||

| 1 y | 92 (87-96) | 4 (66) | 89 (78-96) | 1 (50) | 76 (62-88) | 8 (62) | 87 (83-91) | |||||||

| 2 y | 87 (80-92) | 3 (50) | 86 (74-95) | 1 (50) | 64 (47-80) | 7 (53) | 82 (76-86) | |||||||

CIBMTR, Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research.

OS for age <16 rows and age ≥16 rows on “HLA-identical sibling,” “HLA-mismatched relative,” and “Unrelated donor.” Patient alive for age ≥16, “HLA-matched other relative,” “Other relative,” and “Cord blood.”

Number too small to calculate overall survival rate. Number of patients alive is presented.

Review of publications on HSCT for patients with SCD

| Reference . | N . | Age, median (range), y . | Conditioning . | Stem-cell source (n) . | Follow-up, median (range), y . | OS, % . | EFS, % . | TRM, % . | Graft rejection, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 72 | 50 | 7.5 (0.9-23) | MAC | BM (48), UCB (2) | 5 (0.3-11) | 93 | 82 | 4 | 10 |

| 16 | 59 | 10.1 (3.3-15.9) | MAC | BM | 3.5 (1.0-9.6) | 93 | 84 | 6.7 | 10 |

| 14 | 7* | 9 (3.0-20) | RIC | BM (6), PBMC (1) | 2.3 (1.3-3.3) | 0 | 0 | 100 | |

| 7 | 87 | 9.5 (2-22) | MAC | BM (74), UCB (10), BM/UCB (2), PBMC (1) | 6.0 (2.0-17.9) | 93.1 | 86.1 | 7 | 22.6 (without ATG), 2.9 (with ATG) |

| 74 | 67 | 10 (2-27) | MAC | BM (54), UCB (4), PBSC (9) | 5.1(0.3-14.8) | 97 | 85 | 4 | 13 |

| 17 | 7 | 8 (6-18) | RIC | BM | 4.0 (2.0-8.5) | 86 | 0 | 14 | |

| 9 | 15 | 17 (16-27) | MAC | BM (14), PBMC (1) | 3.4 (1-16.1) | 93 | 93 | 7 | 0 |

| 18 | 17 | 30 (15-46) | RIC | BM | 1.9 (0.61-5.4) | 100 | 0 | 35 | |

| 73 | 8 | 9.1 (2-24) | RIC | BM (6), UCB (1), BM/PBSC (1) | 4 (1-7.7) | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 19 | 30 | 28.5 (17-65) | RIC | PBSC | 3.4 (1-8.6) | 88 | 3 | 13 | |

| 75 | 18 | 8.9 (2.3-20.2) | MAC | BM (15), UCB (3) | 2.9 (0.37-7.48) | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 76 | 13 | 30 (17-40) | RIC | PBSC | 1.8 (1.0-3.7) | 100 | 92 | 0 | 7.7 |

| 77 | 11 | 7 (2-13) | MAC | BM | 3.1 (1-5.7) | 90.9 | 81.9 | 9.1 | 9.1 |

| Reference . | N . | Age, median (range), y . | Conditioning . | Stem-cell source (n) . | Follow-up, median (range), y . | OS, % . | EFS, % . | TRM, % . | Graft rejection, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 72 | 50 | 7.5 (0.9-23) | MAC | BM (48), UCB (2) | 5 (0.3-11) | 93 | 82 | 4 | 10 |

| 16 | 59 | 10.1 (3.3-15.9) | MAC | BM | 3.5 (1.0-9.6) | 93 | 84 | 6.7 | 10 |

| 14 | 7* | 9 (3.0-20) | RIC | BM (6), PBMC (1) | 2.3 (1.3-3.3) | 0 | 0 | 100 | |

| 7 | 87 | 9.5 (2-22) | MAC | BM (74), UCB (10), BM/UCB (2), PBMC (1) | 6.0 (2.0-17.9) | 93.1 | 86.1 | 7 | 22.6 (without ATG), 2.9 (with ATG) |

| 74 | 67 | 10 (2-27) | MAC | BM (54), UCB (4), PBSC (9) | 5.1(0.3-14.8) | 97 | 85 | 4 | 13 |

| 17 | 7 | 8 (6-18) | RIC | BM | 4.0 (2.0-8.5) | 86 | 0 | 14 | |

| 9 | 15 | 17 (16-27) | MAC | BM (14), PBMC (1) | 3.4 (1-16.1) | 93 | 93 | 7 | 0 |

| 18 | 17 | 30 (15-46) | RIC | BM | 1.9 (0.61-5.4) | 100 | 0 | 35 | |

| 73 | 8 | 9.1 (2-24) | RIC | BM (6), UCB (1), BM/PBSC (1) | 4 (1-7.7) | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 19 | 30 | 28.5 (17-65) | RIC | PBSC | 3.4 (1-8.6) | 88 | 3 | 13 | |

| 75 | 18 | 8.9 (2.3-20.2) | MAC | BM (15), UCB (3) | 2.9 (0.37-7.48) | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 76 | 13 | 30 (17-40) | RIC | PBSC | 1.8 (1.0-3.7) | 100 | 92 | 0 | 7.7 |

| 77 | 11 | 7 (2-13) | MAC | BM | 3.1 (1-5.7) | 90.9 | 81.9 | 9.1 | 9.1 |

ATG, antithymocyte globulin; BM, bone marrow; EFS, event-free survival; MAC, myeloablative conditioning; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cell; RIC, reduced-intensity conditioning; TRM, transplantation-related mortality; UCB, umbilical cord blood.

Includes 1 patient with β-thalassemia major.

Outcomes of HSCT using an MAC regimen are best in children. Event-free survival among patients with SCD age 2 to 22 years who underwent HSCT was 95% after 2000.7 However, in older patients or those with alternative donors, the outcomes of MAC transplantation are poorer.8 In a cohort of 15 adults (age 16-27 years) who underwent HSCT using MAC, 1 patient (7%) died on day 32 posttransplantation, 8 patients (53%) developed acute grade ≥2 graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), and 2 patients (13%) had chronic GVHD.9 Also, patients with SCD are prone to developing central nervous system toxicities such as seizures, cognitive impairment, and intracranial hemorrhage posttransplantation.10,11 Late effects of MAC include sterility, ovarian failure, growth failure, and secondary malignancies.12,13 Efforts should be directed to minimize toxicity while maintaining the efficacy of HSCT.

RIC regimens in patients with SCD were initially better tolerated but were associated with high rates of graft failure and recurrence of the underlying disease.14,15 Notably, complete replacement of the hematopoietic system is not necessary to improve the HbS-related physiology, and as little as 10% of donor engraftment is effective if transplanted from an HbAA donor, and 30% to 50% is effective if transplanted from an HbAS (sickle cell trait) donor.16 The reasons for relatively low mixed chimerism being adequate in SCD are that ineffective erythropoiesis by HbSS progenitors allows for a maturation advantage for HbAA or HbAS donor precursor cells, resulting in a greater contribution from donor erythrocyte production. The outcomes of studies using RIC or MAC in SCD are reported in Table 2. In a study with a mostly pediatric population (age 6-18 years), conditioning with busulfan targeted to 900 ng/mL (∼50% of myeloablative dose) for 2 days, fludarabine 35 mg/m2 for 5 days, ATG, and total lymphoid irradiation (5 Gy) in HLA-matched patients resulted in engraftment in 6 of 7 patients.17 In adults, Bolaños-Meade et al18 used fludarabine (30 mg/m2 for 5 days), cyclophosphamide (Cy; 14.5 mg/kg for 2 days), total body irradiation (TBI; 2 Gy), and ATG. In this study, 3 HLA-matched siblings and 14 HLA-haploidentical donors were used. There was no graft failure in HLA-matched patients; however, 6 haploidentical patients rejected their grafts. None experienced severe or chronic GVHD. Engrafted patients had improvement in anemia and hemolysis, and most became transfusion independent. Six patients stopped immunosuppression. Although RIC seems to be safer in adults with end-organ damage, it leads to a tradeoff with graft failure. Additional reductions in intensity such as the minimal-toxicity regimen using alemtuzumab and 3-Gy TBI in HLA-matched donors resulted in 87% long-term engraftment.19 Half of the patients stopped immunosuppression and continued to have mixed chimerism without GVHD. These outcomes were accompanied by stabilization of progression of end-organ dysfunction and by reduced hospitalization and narcotic requirements.

These studies show that patients with SCD conditioned with RIC regimens can achieve reversal of the disease by full-donor chimerism or stable mixed chimerism resulting in decreased hospitalization because of pain crises and prevention of progression of organ damage.

SOT in SCD

Severe SCD often results in end-organ damage, such as cerebrovascular events, nephropathy, hepatopathy, chronic lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, retinopathy, and avascular osteonecrosis.20,21 These complications lead to significant morbidity and mortality. A large prospective cohort study of 1056 patients with SCD observed for >4 decades showed that 12% of the patients developed chronic renal failure at the median age of 37 years. Chronic lung disease occurred in 16%. Irreversible damage to the lung, kidney, and/or liver accounted for 42% of deaths of patients age >20 years.22 Notably, liver disease is likely multifactorial from viral hepatitis, iron overload, and ischemic injury.23 Manci et al24 reported that 74.7% of the patients had evidence of chronic organ injury on autopsy; however, only 25.3% of patients had clinically diagnosed end-organ injury, suggesting that chronic injury in SCD may be underestimated by clinicians.

In the recent era, SOT has gradually emerged as a therapeutic modality in patients with SCD with chronic organ failure. Table 3 lists the publications on SOT for patients with SCD. To date, kidney,25-27 liver,28-30 lung,31 and combined heart-kidney32 and liver-kidney33 transplantations have been reported, with kidney transplantation being the most common. An investigation of outcomes in recipients of renal allografts in the United States revealed that 1-year cadaveric renal allograft survival in recipients with sickle-cell nephropathy was comparable to that in patients with end-stage renal disease from other causes but was significantly poorer at 3 or 6 years.26,27 Additionally, 6-year survival among recipients with SCD was 71%, compared with 84% for the matched cohort with other diagnoses, and was associated with a 3.42-fold increased risk of death. The etiology of mortality was thought to be mainly due to underlying SCD. Notably, recurrence of sickle-cell nephropathy was reported within 0.3 to 3.5 years after transplantation.25,34,35 Other specific complications include acute graft loss from intragraft VOC.36 For liver grafts, acute sickle hepatic crises and recurrent hepatopathy were reported posttransplantation.37-39 These observations suggest that transplanted organs are at risk of injury from sickling and vaso-occlusion and highlight that patients undergoing SOT for complications of SCD should be considered for disease-modifying procedures such as HSCT.

Review of publications on SOT for patients with SCD

| Reference . | N . | Transplanted organ . | 1-y graft survival, % . | 1-y patient survival, % . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 78 | 30 | Kidney | 67 | 86 | |

| 34 | 1 | Kidney | Recurrent SCN after 3.5 y | ||

| 79 | 40 | Kidney | 82 (live), 62 (cadaveric) | 88 | |

| 25 | 5 | Kidney | 100 | 100 | Recurrent SCN in 2 patients |

| 80 | Kidney | 89 | 89 | ||

| 26 | 82 | Kidney | 78 | 78 | |

| 81 | 59 | Kidney | 82.5 | 90.5 | |

| 58 | 13 | Kidney | NA | NA | |

| 82 | 2 | Kidney | 100 | 100 | |

| 83 | 237 | Kidney | NA | NA | |

| 36 | 2 | Kidney | 0 | Acute graft loss from intragraft VOC | |

| 27 | 67 (1988-1999), 106 (2000-2011) | Kidney | 6 y: 45.9 (1988-1999), 50.8 (2000-2011) | 6 y: 55.7 (1988-1999), 69.8 (2000-2011) | |

| 84 | 1 | Kidney | 100 | 100 | |

| 31 | 1 | Lung | 100 | 100 | |

| 85 | 1 | Liver | 100 | 100 | |

| 28 | 1 | Liver | |||

| 86 | 1 | Liver | 100 | 100 | |

| 29 | 1 | Liver | 0 | 0 | |

| 87 | 1 | Liver | 100 | 100 | |

| 88 | 1 | Liver | 100 | 100 | |

| 89 | 2 | Liver | 0 | 0 | |

| 37 | 3 | Liver | 100 | 100 | Recurrent hepatopathy in 1 patient |

| 90 | 1 | Liver | |||

| 38 | 1 | Liver | Acute sickle hepatic crisis after 3 mo | ||

| 91 | 6 | Liver | 83.3 | ||

| 92 | 1 | Liver | 100 | 100 | |

| 93 | 1 | Liver | |||

| 33 | 1 | Liver and kidney | 100 | 100 |

| Reference . | N . | Transplanted organ . | 1-y graft survival, % . | 1-y patient survival, % . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 78 | 30 | Kidney | 67 | 86 | |

| 34 | 1 | Kidney | Recurrent SCN after 3.5 y | ||

| 79 | 40 | Kidney | 82 (live), 62 (cadaveric) | 88 | |

| 25 | 5 | Kidney | 100 | 100 | Recurrent SCN in 2 patients |

| 80 | Kidney | 89 | 89 | ||

| 26 | 82 | Kidney | 78 | 78 | |

| 81 | 59 | Kidney | 82.5 | 90.5 | |

| 58 | 13 | Kidney | NA | NA | |

| 82 | 2 | Kidney | 100 | 100 | |

| 83 | 237 | Kidney | NA | NA | |

| 36 | 2 | Kidney | 0 | Acute graft loss from intragraft VOC | |

| 27 | 67 (1988-1999), 106 (2000-2011) | Kidney | 6 y: 45.9 (1988-1999), 50.8 (2000-2011) | 6 y: 55.7 (1988-1999), 69.8 (2000-2011) | |

| 84 | 1 | Kidney | 100 | 100 | |

| 31 | 1 | Lung | 100 | 100 | |

| 85 | 1 | Liver | 100 | 100 | |

| 28 | 1 | Liver | |||

| 86 | 1 | Liver | 100 | 100 | |

| 29 | 1 | Liver | 0 | 0 | |

| 87 | 1 | Liver | 100 | 100 | |

| 88 | 1 | Liver | 100 | 100 | |

| 89 | 2 | Liver | 0 | 0 | |

| 37 | 3 | Liver | 100 | 100 | Recurrent hepatopathy in 1 patient |

| 90 | 1 | Liver | |||

| 38 | 1 | Liver | Acute sickle hepatic crisis after 3 mo | ||

| 91 | 6 | Liver | 83.3 | ||

| 92 | 1 | Liver | 100 | 100 | |

| 93 | 1 | Liver | |||

| 33 | 1 | Liver and kidney | 100 | 100 |

NA, not available; SCN, sickle-cell nephropathy.

Dual transplantation of HSCs and SOs

One potential solution to reverse both SCD and end-organ damage is dual HSCT and SOT. Despite being developed largely independently, HSCT and SOT share many biological principles. Immunosuppressants to prevent graft rejection overlap with those for prevention of GVHD. There are many reports of SOT being performed after HSCT or vice versa (Table 4). These patients either underwent SOT to treat a complication of HSCT or underwent HSCT after incidentally developing hematologic malignancy after organ transplantation. It is well established that HSCT MAC provides donor-specific tolerance to SO grafts even across HLA barriers.40-43 The induction of organ allograft tolerance through mixed chimerism using reduced-intensity regimens for HSCT has also been reported.44-46 The mechanisms of organ tolerance induced by HSCT after less T-cell–ablative regimens include central and peripheral clonal deletion, anergy, and immune regulation.47,48

Review of publications of HSCT and SOT for any indications

| Reference . | N . | Age, y . | Transplanted SO . | Primary disease (n) . | Indication for secondary transplantation (n) . | Time between SOT and BMT . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOT after BMT | ||||||

| 94 | 13 | 4.5-50 | Kidney | AML (5), CML (3), ALL (2), WAS (1), SAA (1), FA (1) | BMT nephropathy (4), RF (4), membranous nephritis (1), MPGN (1), radiation nephritis (1), HUS (2) | 1-10 y |

| 14 | 4-47 | Liver | AML (4), CML (3), ALL (3), MDS (2), NHL (1), SD/SAA (1) | VOD (9), GVHD (4), GVHD cirrhosis (1) | 0.06-3 y | |

| 9 | 3-37 | Lung | AML (1), CML (1), ALL (4), WAS (1), SAA (1), ID (1) | GVHD (6), lung fibrosis (1), restrictive lung disease (1), radiation pneumonitis (1) | 1.3-14 y | |

| 1 | 26 | Heart | AML | Cardiomyopathy | 1 y | |

| BMT for malignancy after SOT | ||||||

| 94 | 7 | 0.3-45 | Liver | Hepatitis (5), ALF (1), hepatitis B and lymphoma (1) | SAA (5), recurrent lymphoma (1), HLH (1) | 0.17-3.7 y |

| 4 | 30-42 | Kidney | Focal GS (2), chronic GN (1), progressive GN (1) | AML (1), AML relapse (1), lymphoma (1), prolymphocytic leukemia (1) | 7.5-10 y | |

| 1 | 23 | Heart | Viral cardiomyopathy | MDS | 10 y | |

| Combined BMT and SOT | ||||||

| 95 | 1 | 43 | Liver | Breast cancer liver metastasis | 85 d | |

| 50 | 1 | 18 | Liver | Hyper-IgM syndrome and cholangiopathy | 34 d | |

| 96 | 7 | 34-55 | Kidney | MM and ESRD | Same day | |

| 51 | 10 | 22-46 | Kidney | Alport (4), PKD (2), MPGN (2), reflux uropathy (1), focal GS (1) | Same day | |

| 52 | 19 | 18-64 | Kidney | Alport (1), PKD (4), IgA (3), DM (2), MPGN (1), HTN (3), membranous (1), chronic GN (1), urinary reflux (2), unknown (1) | 1 d | |

| 53 | 38 | 21-62 | Kidney | Alport (1), PKD (4), IgA (10), SLE (4), DM (2), GN (2), FSGS (1), dysplasia (1), urinary reflux (1), CIN (1), obstruction (1), unknown (10) | Same day | |

| 54 | 4 | 38-67 | Kidney | MM and ESRD (3), HD and ESRD (1) | Same day | |

| 97 | 1 | 30 | Kidney | MM and ESRD |

| Reference . | N . | Age, y . | Transplanted SO . | Primary disease (n) . | Indication for secondary transplantation (n) . | Time between SOT and BMT . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOT after BMT | ||||||

| 94 | 13 | 4.5-50 | Kidney | AML (5), CML (3), ALL (2), WAS (1), SAA (1), FA (1) | BMT nephropathy (4), RF (4), membranous nephritis (1), MPGN (1), radiation nephritis (1), HUS (2) | 1-10 y |

| 14 | 4-47 | Liver | AML (4), CML (3), ALL (3), MDS (2), NHL (1), SD/SAA (1) | VOD (9), GVHD (4), GVHD cirrhosis (1) | 0.06-3 y | |

| 9 | 3-37 | Lung | AML (1), CML (1), ALL (4), WAS (1), SAA (1), ID (1) | GVHD (6), lung fibrosis (1), restrictive lung disease (1), radiation pneumonitis (1) | 1.3-14 y | |

| 1 | 26 | Heart | AML | Cardiomyopathy | 1 y | |

| BMT for malignancy after SOT | ||||||

| 94 | 7 | 0.3-45 | Liver | Hepatitis (5), ALF (1), hepatitis B and lymphoma (1) | SAA (5), recurrent lymphoma (1), HLH (1) | 0.17-3.7 y |

| 4 | 30-42 | Kidney | Focal GS (2), chronic GN (1), progressive GN (1) | AML (1), AML relapse (1), lymphoma (1), prolymphocytic leukemia (1) | 7.5-10 y | |

| 1 | 23 | Heart | Viral cardiomyopathy | MDS | 10 y | |

| Combined BMT and SOT | ||||||

| 95 | 1 | 43 | Liver | Breast cancer liver metastasis | 85 d | |

| 50 | 1 | 18 | Liver | Hyper-IgM syndrome and cholangiopathy | 34 d | |

| 96 | 7 | 34-55 | Kidney | MM and ESRD | Same day | |

| 51 | 10 | 22-46 | Kidney | Alport (4), PKD (2), MPGN (2), reflux uropathy (1), focal GS (1) | Same day | |

| 52 | 19 | 18-64 | Kidney | Alport (1), PKD (4), IgA (3), DM (2), MPGN (1), HTN (3), membranous (1), chronic GN (1), urinary reflux (2), unknown (1) | 1 d | |

| 53 | 38 | 21-62 | Kidney | Alport (1), PKD (4), IgA (10), SLE (4), DM (2), GN (2), FSGS (1), dysplasia (1), urinary reflux (1), CIN (1), obstruction (1), unknown (10) | Same day | |

| 54 | 4 | 38-67 | Kidney | MM and ESRD (3), HD and ESRD (1) | Same day | |

| 97 | 1 | 30 | Kidney | MM and ESRD |

ALF, acute liver failure; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BMT, bone marrow transplantation; CIN, chronic interstitial nephritis; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; DM, diabetes mellitus; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; FA, Fanconi anemia; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; GN, glomerulonephritis; GS, glomerulosclerosis; HD, Hodgkin disease; HLH, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; HTN, hypertension; HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome; ID, immune deficiency; Ig, immunoglobulin; MDS, myelodysplasia; MM, multiple myeloma; MPGN, membranous proliferative glomerulonephritis; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; PKD, polycystic kidney disease; RF, renal failure; SAA, severe aplastic anemia; SD, Shwachman-Diamond syndrome; VOD, veno-occlusive disease; WAS, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome.

Dual (prospectively planned) transplantation of HSCs and SOs (dual HSCT/SOT) was initially performed to treat both end-organ damage and hematologic disease, such as multiple myeloma with end-stage renal disease or hyper–immunoglobulin M syndrome with cholangiopathy.49,50 Recently, this procedure has been used to induce graft tolerance in patients without underlying hematologic disease.51-53 This approach allows HLA-mismatched grafting for transplantation by inducing durable or transient lymphohematopoietic chimerism in recipients without developing GVHD. This also potentially allows for withdrawal of immunosuppressants; for example, Leventhal et al52 reported that 12 of 19 patients who received HLA-mismatched kidney transplants combined with HSCT from the same donor were successfully weaned from immunosuppressants. To our knowledge, there is no report of prospective dual transplantation for SCD specifically, although there is an ongoing clinical trial for patients with ESRD and hematologic disorders including SCD (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT01758042).

The conditioning regimen should be modified for reduced renal or hepatic function. Experiences in combined HSCT and kidney transplantation for patients with multiple myeloma and end-stage renal disease revealed that a regimen of Cy 60 mg/kg, ATG, and thymus irradiation at 7 Gy with hemodialysis after each Cy dose was tolerated.54 The same group used a reduced-intensity regimen consisting of Cy 14.5 mg/kg for 2 days, fludarabine 24 mg/m2 for 3 days with hemodialysis, and TBI at 2 Gy on day −1 and successfully performed HSCT from haploidentical donors. As mentioned previously, correction of the sickle phenotype does not require 100% chimerism, and although less ablative regimens lead to risks of HSC graft failure or rejection, we propose the conditioning regimen of Cy 14.5 mg/kg on days −6 and −5 and fludarabine 25 to 30 mg/m2 on days −4 to −2 with TBI at 2 Gy on day −1, followed by posttransplantation Cy 50 mg/kg on days +3 and +4, followed by mycophenolate and tacrolimus as previously reported.55 Addition of ATG may also be considered to reduce graft rejection.

Benefits and limitations of dual SOT and HSCT for SCD

There have been many improvements in management of SCD, and a number of exciting new treatment approaches are being developed, including gene therapy.56,57 Currently, HSCT is the only approach with proven curative potential in SCD. However, because of the potential for transplantation-related morbidity and mortality and particularly in the setting of comorbidities, HSCT is less often considered as a treatment option. Because of the inability to accurately identify patients at highest risk for SCD-related morbidity and mortality before the development of end-organ damage, by the time such patients are identified as being at the highest risk, they have already experienced end-organ damage either precluding HSCT or significantly increasing the risks in HSCT. In addition, previous experience in SOT to replace damaged organs as sequelae of SCD indicates that the same organ injury from SCD occurs in the grafts.

Dual HSCT/SOT may benefit patients with severe SCD by reversing the disease and the chronic organ injury resulting from the disease. Dual transplantation will primarily apply to those who have developed end-organ dysfunction from SCD, such as nephropathy or hepatopathy. On the basis of the US Renal Data System Annual Report, it is estimated that 0.1% of the dialysis population has SCD,58 and such patients are therefore potential candidates for dual transplantation. By combining these transplantations, organs from the HSCT donor may benefit from immunological tolerance, thus limiting the exposure of patients to long-term immunosuppressants. RIC regimens for HSCT can reduce transplantation-related morbidity and mortality while allowing mixed donor chimerism and have successfully reversed SCD clinically.

Challenges of dual HSCT/SOT in patients with SCD include adjusting the HSCT conditioning regimen in the setting of chronic organ dysfunction as discussed previously, optimization of HbS burden to avoid perioperative VOC, HLA and red blood cell sensitization from prior transfusions, and donor selection.

Current perioperative guidelines recommend against aggressive transfusion because it does not lower SCD-specific complications.59 Transfusion to achieve a hematocrit of 30% may be beneficial for patients at moderate to high risk. Prior HLA sensitization from multiple transfusions is problematic because the presence of anti-HLA antibodies to the donor’s mismatched HLA in the setting of haploidentical HSCT increases the risk of graft failure.60,61 In SCD, HLA alloimmunization is detected in 18% to 47% of patients and red blood cell alloimmunization in 4% to 47%.62,63 For both HSCT and SOT, desensitization therapy can include plasmapheresis, IV immunoglobulin, rituximab, bortezomib, Cy, and polyclonal antilymphocyte antibodies.64-66 These regimens should be further studied specifically in patients with SCD.

Donor selection for dual HSCT/SOT will likely be a limiting factor. Huang et al27 reported that 106 renal transplantations were performed in patients with SCD from 2000 to 2011, and among those, 76.4% received cadaveric allografts and only 25 patients received grafts from living donors.27 Currently, collecting HSCs from cadavers is problematic; therefore, both HSCs and SOs should ideally come from the same living donor. It is estimated that only 14% to 20% of patients with SCD have unaffected HLA-matched sibling donors.67 However, of these, the number who have unaffected organs and are willing and eligible to donate their organs would likely be much smaller. If these donors are unavailable, haploidentical or mismatched donors would be an option. Donors can have HbAS (sickle-cell trait) because the safety of stem-cell mobilization using granulocyte colony-stimulating factor has been shown previously, and there were no major differences in outcomes of HSCT.68,69 Dual transplantation for multiple myeloma with end-stage renal disease using haploidentical donors54 or HSCT for patients with SCD using mismatched family members or unrelated donors has been successful.70 Additionally, paired exchanges of SOs could potentially increase the donor pool.71 These approaches may provide a reliable pool of motivated, appropriate donors from whom a suitable organ/stem-cell donor could be selected. Another alternative may be to use different donors as sources for HSCT and SOT. This approach would increase the pool of donors and potential recipients, at the cost of inability to generate donor-specific tolerance and with potential for complicated 3-way alloimmunity interactions between the patient, the HSC graft, and the SO graft.

Conclusion

SCD results in severe morbidity and mortality by causing multiple hospitalizations, end-organ dysfunction, and early mortality. The limited application of SOT and HSCT to date is due to the concern for recurrent organ dysfunction from SCD and concern for morbidity and mortality from HSCT. Combined transplantation of HSCs and SOs has become more feasible because of the development of nonmyeloablative and reduced-intensity regimens and improved supportive care, but there is still a risk of significant morbidity and mortality. Identifying patients most at risk for disease-related morbidity and mortality will be critical for the application of dual transplantation. Protocols will need to be designed to select patients for dual HSCT/SOT to treat both the underlying disease and its complications simultaneously, with multidisciplinary involvement of the appropriate teams.

Authorship

Contribution: H.H. wrote the manuscript; H.H. and S.G. designed tables and figure; and J.L., P.A., D.H., D.L.P., and S.G. revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Saar Gill, University of Pennsylvania, 3400 Civic Center Blvd, Philadelphia, PA 19104; e-mail: saargill@pennmedicine.upenn.edu.