Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a major health care and societal problem that affects millions of people worldwide.

In low-income countries like Malawi, basic facilities for management are lacking, systematic screening is not present, and diagnosis is often made late.

Before January 2015, children suspected of having SCD at Kamuzu Central Hospital (KCH; a referral hospital in Lilongwe) were seen in the general pediatric clinic together with children with various chronic medical conditions.

The diagnosis was made clinically, with a few children diagnosed by Sickledex; the supply of drugs was erratic, and time was limited for patient and caregiver SCD education.

In January 2015, a weekly dedicated Sickle Cell Clinic was established at KCH, and hemoglobin electrophoresis capabilities were introduced.

The clinic together with a concurrent observational study aims to establish a prospective longitudinal SCD cohort in Malawi and determine clinical characteristics, acute and chronic complications, and the laboratory profile of patients with confirmed SCD.

Methods

Study participants were recruited from a general pediatric clinic, the children’s ward at KCH, and surrounding health facilities (Figure 1).

Clinical and laboratory data were collected longitudinally at 6-month intervals during routine care. Loss-to-follow-up was defined as no study visit in 12 months.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software.

Written informed consent was obtained from parents of all enrolled children. Children age 7 to 17 years also provided informed assent prior to study participation.

The study was approved by the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill institutional review board and the Malawi National Health Science Review Committee.

Capacity building

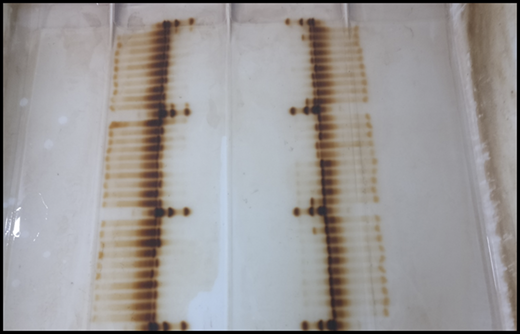

Because the SCD clinic is now available, hemoglobin electrophoresis can be used to make the diagnosis in individuals suspected of having SCD at KCH (Figures 2 and 3).

Laboratory technicians have been trained to perform hemoglobin electrophoresis and interpret results. The site laboratory is now capable of conducting large-scale screening studies for SCD.

Having a dedicated team of nurses and clinicians running the Sickle Cell Clinic every week has led to better understanding of the disease and enhanced knowledge and skills in patient care.

Results

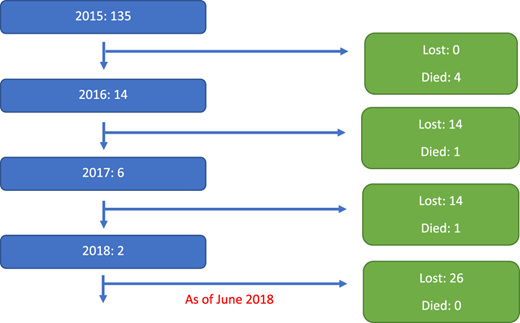

Enrollment of new participants and loss-to-follow-up by year (N = 157).

Demographic and follow-up characteristics of the study cohort

| Characteristic . | Count . | % . | n* . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 79 | 51.6 | 153 |

| Female | 74 | 48.4 | 153 |

| Lilongwe District | 120 | 90.2 | 133 |

| Lost to follow-up (after 12 months) | 54 | 34.4 | 157 |

| Deceased | 6 | 3.8 | 157 |

| HbSS | 155 | 98.7 | 157 |

| HbSc | 1 | 0.6 | 157 |

| HbFS | 1 | 0.6 | 157 |

| Median | Range or IQR | n* | |

| Age at enrollment, years | 7 | Range, 0-20 | 148 |

| Duration of follow-up, months | 27 | IQR, 24-36 | 135 |

| No. of follow-up study visits | 3 | IQR, 2-4 | 157 |

| Characteristic . | Count . | % . | n* . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 79 | 51.6 | 153 |

| Female | 74 | 48.4 | 153 |

| Lilongwe District | 120 | 90.2 | 133 |

| Lost to follow-up (after 12 months) | 54 | 34.4 | 157 |

| Deceased | 6 | 3.8 | 157 |

| HbSS | 155 | 98.7 | 157 |

| HbSc | 1 | 0.6 | 157 |

| HbFS | 1 | 0.6 | 157 |

| Median | Range or IQR | n* | |

| Age at enrollment, years | 7 | Range, 0-20 | 148 |

| Duration of follow-up, months | 27 | IQR, 24-36 | 135 |

| No. of follow-up study visits | 3 | IQR, 2-4 | 157 |

HbFS, fetal hemoglobin sickle cell; HbSc, sickle cell hemoglobin C; HbSS, homozygous sickle cell; IQR, interquartile range.

n represents total number of patients in the subgroup.

Lifetime medical history at enrollment

| . | No. of patients (N = 154)* . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Malaria | 58 | 37.7 |

| Tuberculosis | 8 | 5.2 |

| Pneumonia | 2 | 1.3 |

| Anemia | 96 | 62.3 |

| Fever | 13 | 8.4 |

| Pain crisis | 72 | 46.8 |

| Jaundice | 77 | 50.0 |

| Shortness of breath | 23 | 14.9 |

| Chest pain | 32 | 20.8 |

| Joint pain | 79 | 51.3 |

| Dactylitis | 47 | 30.5 |

| Total No. of blood transfusions | ||

| 1-5 | 18 | 11.7 |

| 6-10 | 1 | 0.6 |

| 11-20 | 0 | 0 |

| 21-30 | 0 | 0 |

| 31-50 | 0 | 0 |

| Hospital admissions | 1 (median) | 0-8 (range) |

| Pneumococcal vaccine | 20 | 13.0 |

| . | No. of patients (N = 154)* . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Malaria | 58 | 37.7 |

| Tuberculosis | 8 | 5.2 |

| Pneumonia | 2 | 1.3 |

| Anemia | 96 | 62.3 |

| Fever | 13 | 8.4 |

| Pain crisis | 72 | 46.8 |

| Jaundice | 77 | 50.0 |

| Shortness of breath | 23 | 14.9 |

| Chest pain | 32 | 20.8 |

| Joint pain | 79 | 51.3 |

| Dactylitis | 47 | 30.5 |

| Total No. of blood transfusions | ||

| 1-5 | 18 | 11.7 |

| 6-10 | 1 | 0.6 |

| 11-20 | 0 | 0 |

| 21-30 | 0 | 0 |

| 31-50 | 0 | 0 |

| Hospital admissions | 1 (median) | 0-8 (range) |

| Pneumococcal vaccine | 20 | 13.0 |

Not all participants had medical history information recorded.

Medications at enrollment visit and as a proportion of all return visits

| Medication . | First visit . | All return visits . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (N = 151)* . | % . | No. (N = 451) . | % . | |

| Folic acid | 21 | 13.9 | 438 | 97.1 |

| Fansidar | 18 | 11.9 | 414 | 91.8 |

| Azithromycin, penicillin V, amoxicillin | 19 | 12.6 | 441 | 97.8 |

| Hydroxyurea | 5 | 3.3 | 126 | 27.9 |

| Medication . | First visit . | All return visits . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (N = 151)* . | % . | No. (N = 451) . | % . | |

| Folic acid | 21 | 13.9 | 438 | 97.1 |

| Fansidar | 18 | 11.9 | 414 | 91.8 |

| Azithromycin, penicillin V, amoxicillin | 19 | 12.6 | 441 | 97.8 |

| Hydroxyurea | 5 | 3.3 | 126 | 27.9 |

Not all participants had medical history information recorded.

Physical examination characteristics at enrollment and at last recorded study visit

| Characteristic . | First visit . | Last visit . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (N = 151)* . | % . | No. (N = 138)† . | % . | |

| Jaundice | 7 | 4.6 | 11 | 8.0 |

| Frontal bossing | 4 | 2.7 | 13 | 9.4 |

| Murmur | 2 | 1.3 | 9 | 6.5 |

| Hepatomegaly | 26 | 17.2 | 19 | 13.8 |

| Splenomegaly | 5 | 3.3 | 10 | 7.3 |

| Clubbing | 4 | 2.7 | 2 | 1.5 |

| Leg ulcers | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2.9 |

| Dactylitis | 2 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Joint swelling | 2 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Characteristic . | First visit . | Last visit . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (N = 151)* . | % . | No. (N = 138)† . | % . | |

| Jaundice | 7 | 4.6 | 11 | 8.0 |

| Frontal bossing | 4 | 2.7 | 13 | 9.4 |

| Murmur | 2 | 1.3 | 9 | 6.5 |

| Hepatomegaly | 26 | 17.2 | 19 | 13.8 |

| Splenomegaly | 5 | 3.3 | 10 | 7.3 |

| Clubbing | 4 | 2.7 | 2 | 1.5 |

| Leg ulcers | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2.9 |

| Dactylitis | 2 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Joint swelling | 2 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 |

Not all participants had medical history information recorded.

The most recent study follow-up visit (excluding the enrollment visit).

Laboratory results at first and last recorded follow-up visits

| Laboratory test . | First visit* . | Last visit . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of tests done . | Median . | Range . | No. of tests done . | Median . | Range . | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 137 | 7.4 | 5.1-10.4 | 140 | 7.6 | 3.6-13.0 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 137 | 0.3 | 0.1-1.2 | 105 | 0.36 | 0.14-7.22 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 136 | 653 | 309-1748 | 104 | 638.5 | 204-2117 |

| No. of positive tests | % | No. of positive tests | % | |||

| Urine protein | 145 | 11 | 7.6 | 164 | 15 | 9.2 |

| Blood in urine | 145 | 54 | 26.2 | 164 | 49 | 29.9 |

| Laboratory test . | First visit* . | Last visit . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of tests done . | Median . | Range . | No. of tests done . | Median . | Range . | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 137 | 7.4 | 5.1-10.4 | 140 | 7.6 | 3.6-13.0 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 137 | 0.3 | 0.1-1.2 | 105 | 0.36 | 0.14-7.22 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 136 | 653 | 309-1748 | 104 | 638.5 | 204-2117 |

| No. of positive tests | % | No. of positive tests | % | |||

| Urine protein | 145 | 11 | 7.6 | 164 | 15 | 9.2 |

| Blood in urine | 145 | 54 | 26.2 | 164 | 49 | 29.9 |

Not all participants had medical history information recorded.

Conclusion

Most children presented with a history of malaria, a major cause of morbidity and mortality in children with SCD in Malawi. Anemia and a history of blood transfusion were common in patients who presented with SCD. Screening children who present with anemia may lead to early diagnosis of SCD. Parents are educated about the importance of prophylaxis, prompt treatment of infections, immunizations, and mosquito netting. Our cohort shows a low death rate, but the rate of loss to follow-up is concerning. A community tracking program of bringing patients back to care and ascertainment of health status including verbal autopsies is needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Robert Krysiak, Godwin Chipoka, Zondwayo Tembo, and Yacinta Majawa (University of North Carolina Project-Malawi).

This work was funded by the Fulbright-Fogarty Training Program, National Institutes of Health Fogarty International Center, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (U01HL117659).

Authorship

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: N.K. received research funding from UniQure BV. K.A. received research funding from Pfizer and Global Blood Therapeutics; received honoraria from Modus Therapeutics, Global Blood Therapeutics, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, and Bioverativ; served as a member of the board of directors or on advisory committees for Global Blood Therapeutics; and served as a member of various entities of Bioverativ. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Portia Kamthunzi, University of North Carolina Project-Malawi, Lilongwe, Malawi; e-mail: pkamthunzi@unclilongwe.org.