Key Points

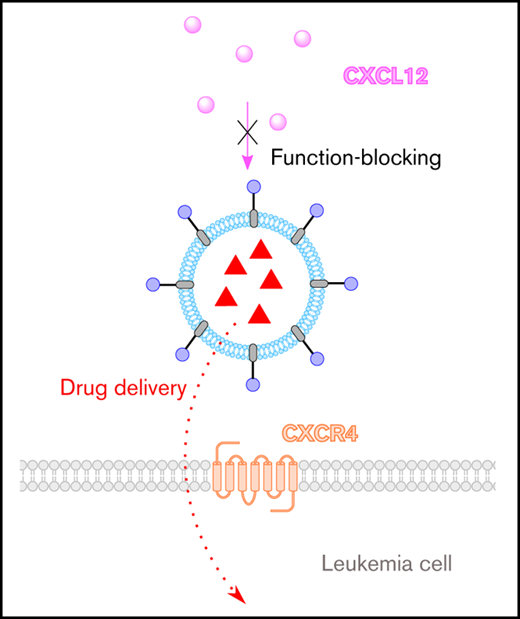

We have developed a novel drug-delivery system that delivers cancer therapeutics and blocks CXCR4’s interaction with CXCL12.

The drug-delivery system is modular and versatile, allowing it to be tailored to other hematological cancers in which CXCR4 is implicated.

Abstract

CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) is overexpressed by a broad range of hematological disorders, and its interaction with CXC chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12) is of central importance in the retention and chemoprotection of neoplastic cells in the bone marrow and lymphoid organs. In this article, we describe the biological evaluation of a new CXCR4-targeting and -antagonizing molecule (BAT1) that we designed and show that, when incorporated into a liposomal drug delivery system, it can be used to deliver cancer therapeutics at high levels to chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells. CXCR4 targeting and antagonism by BAT1 were demonstrated alone and following its incorporation into liposomes (BAT1-liposomes). Antagonism of BAT1 against the CXCR4/CXCL12 interaction was demonstrated through signaling inhibition and function blocking: BAT1 reduced ERK phosphorylation and cell migration to levels equivalent to those seen in the absence of CXCL12 stimulation (P < .001). Specific uptake of BAT1-liposomes and delivery of a therapeutic cargo to the cell nucleus was seen within 3 hours of incubation and induced significantly more CLL cell death after 24 hours than control liposomes (P = .004). The BAT1 drug-delivery system is modular, versatile, and highly clinically relevant, incorporating elements of proven clinical efficacy. The combined capabilities to block CXCL12-induced migration and intracellular signaling while simultaneously delivering therapeutic cargo mean that the BAT1-liposome drug-delivery system could be a timely and relevant treatment of a range of hematological disorders, particularly because the therapeutic cargo can be tailored to the disease being treated.

Introduction

Drug-delivery systems are nanoscale objects that store therapeutic agents, releasing them upon uptake into target cells. Targeting ligands (most commonly binding a receptor overexpressed on the cell) can be used to decorate the drug-delivery system and provide specificity for target cells, such as cancer cells.1-3 In some instances, the interaction between targeting ligands and cell receptors can be further exploited to block or modify important cell functions, achieving additional chemosensitizing or disease-modifying effects. The most widely used drug-delivery vehicles in clinical practice are liposomes. Nontargeted liposomes encapsulating drugs such as doxorubicin, cytarabine, or vincristine have been used in the treatment of hematological cancers,4-6 and research into the use of targeting agents in hematological malignancies is ongoing7-9 ; however, the field remains underdeveloped. In this article, we present the use of the novel CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4)–targeting drug BAT1 (referred to as molecule 1 in our prior publication)10 incorporated into liposomes (BAT1-liposomes). We demonstrate that BAT1-liposomes combine function blocking and effective drug delivery to primary chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) lymphocytes. This highly adaptable system has the potential to be used in a range of hematological cancers in which CXCR4 plays an important role.11,12

CXCR4 is overexpressed in >20 cancers, including CLL, where its role has been studied in depth.13-17 In CLL, CXCR4 plays a significant role in the interaction between neoplastic cells and their microenvironment through CXC chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12), which is central to the emergence of cells that are resistant to standard treatment and, therefore, are referred to as the chemoprotective niche.18-20 Bis(cyclam) compounds are a class of high-affinity CXCR4 antagonists, with the class-leading drug (plerixafor) licensed for clinical use.21 In CLL, several studies have found that plerixafor disrupts lymphocyte interactions within the bone marrow microenvironment,14,20,22 leading to increased CLL cell sensitization to standard therapies. Promising results from clinical trials using plerixafor in combination therapies suggest that bis(cyclam) compounds may lead to improved patient outcomes when administered with other therapeutics.23-25

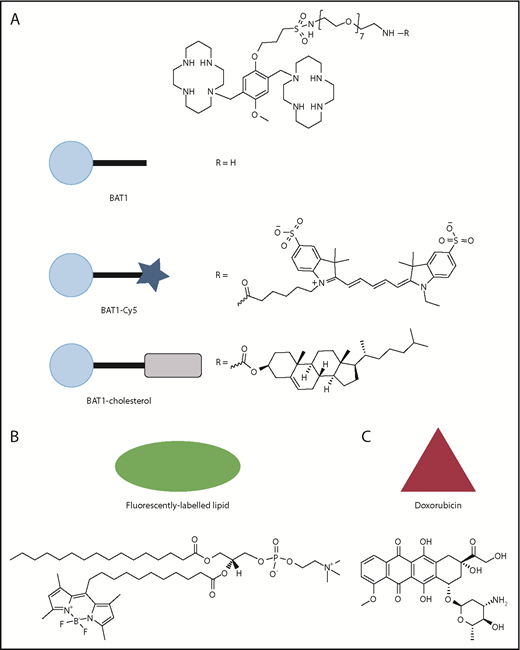

The ability of plerixafor to tightly bind CXCR4 makes it an attractive choice for use in targeted drug delivery.18,26-29 However, plerixafor is not readily attached to drug-delivery systems, because chemical modification occurs primarily through the molecule’s cyclam groups, which significantly reduces its affinity to CXCR4.28 To overcome this barrier, we have synthesized a bis(cyclam) compound (BAT1) with a flexible tether attached to the aromatic core that allows easy conjugation to other molecules while retaining a high affinity to CXCR410 (Figure 1A). In this article, we show that, following conjugation to nanoparticles, BAT1 can be used to target liposomally encapsulated chemotherapy drugs to CLL lymphocytes while retaining the capability to block intracellular signaling and migration responses of CLL cells to CXCL12.

Molecular structures of the compounds used in this article, with the symbols used for schematic representations. (A) Structure of BAT1, and its derivatives, BAT1-Cy5 (fluorescently labeled BAT1 conjugate) and BAT1-cholesterol (used to decorate liposomes with BAT1). (B) Structure of the fluorescently labeled lipid, TopFluor, which was used to label liposomal membranes for ease of tracking. (C) Structure of doxorubicin, the drug cargo loaded into liposomes and delivered using BAT1 targeting.

Molecular structures of the compounds used in this article, with the symbols used for schematic representations. (A) Structure of BAT1, and its derivatives, BAT1-Cy5 (fluorescently labeled BAT1 conjugate) and BAT1-cholesterol (used to decorate liposomes with BAT1). (B) Structure of the fluorescently labeled lipid, TopFluor, which was used to label liposomal membranes for ease of tracking. (C) Structure of doxorubicin, the drug cargo loaded into liposomes and delivered using BAT1 targeting.

Methods

General reagents

Unless otherwise stated, all reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Gillingham, United Kingdom). Details about all antibodies, including their suppliers and the concentrations used, can be found in supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

Preparation of BAT1 liposomes

BAT1 and the conjugate between BAT1 and cholesterol (BAT1-cholesterol) were prepared as described previously.10 For analysis, conjugation to the Cy5-NHS ester was performed as follows: BAT1 (3 µmol) was mixed with Cy5-NHS ester (1 molar equivalent) in 3 mL of Milli-Q water and then stirred overnight at room temperature. The mixture was purified using high-performance liquid chromatography (supplemental Methods and data) and nuclear magnetic resonance and mass spectrometry analysis were used to confirm conjugation (supplemental Figures 1 and 2). The reaction can also be performed directly in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4). Mass spectrometry MS (ESI+) calculated for C81H137N12O18S3 [M + 3H]3+ = 553.9773, found: 553.9837 and calculated for C81H137N12O18S3Na [M + H + Na]2+ = 841.9550, found: 841.9640.

Liposomes were prepared using standard methods30 (supplemental Methods and data), incorporating the following phospholipids (PLs): 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine, and 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol). The ζ potential of all preparations was measured in buffer (HEPES buffer: 25 mM with 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5), at PL concentrations of 10 mM, using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZSP at 25°C. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements were performed in Milli-Q water (concentration: 10 mM of PLs) on a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZSP 633-nm laser at 25°C (3 runs of 12 scans per sample) and a scattering angle of 173° using the diffusion barrier method.31 Doxorubicin was actively loaded into DOPC liposomes using a pH gradient under standard methods32 (supplemental Methods and data), and the quantity loaded was quantified using UV–visible absorption spectroscopy (supplemental Figure 7).

Biological analysis

Cells and culture.

Primary human CLL peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were collected with informed consent and full Research Ethics Committee (REC) approval: Manchester REC reference 10/H1017/73, Plymouth REC reference 14/EE/1251. Details of disease characteristics and cases are provided in supplemental Table 3. Cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 using RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 1% l-glutamine, and 1% penicillin streptomycin, with cell densities between 1 and 4 × 106 cells per milliliter, depending on the assay. CLL PBMCs were used without further purification.

In some liposomal-uptake assays (indicated in “Results” and in the figure legends), cells were cocultured with murine fibroblasts stably transfected with the CD40 ligand (CD40L murine fibroblasts; donated by C.V.H.). This coculture reproduces some of the stromal interactions present in vivo and alters membrane CXCR4 expression (supplemental Figure 5). Experiments were performed by coculturing the CLL cells with CD40L murine fibroblasts at 70% confluency for 24 hours before incubation with the liposomes.

Immunohistochemistry.

Sections of normal or CLL tissue were kindly donated by Richard Byers (Division of Cancer Sciences, University of Manchester). Preparation used standard deparaffinization (Histo-Clear II; Scientific Laboratory Supplies, Nottingham, United Kingdom) and antigen retrieval (10 mM sodium citrate at 65°C; Thermo Fisher, Altrincham, United Kingdom) before blocking with H2O2 and protein block (Mouse and Rabbit Specific HRP/DAB [ABC] Detection IHC Kit; Abcam PLC, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Immunostaining used CXCR4 or CXCR7 antibodies overnight at 4°C.

Flow cytometry.

Analysis used a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer and BD FACSDiva and FlowJo v10 software.

Competition assays.

After culturing overnight, cells were incubated for 3 hours with BAT1 or plerixafor (R&D Systems, Abingdon, United Kingdom). Concentrations are indicated in the figures. CXCR4 and CXCR7 antibody staining (15 minutes, room temperature) was performed, followed by fixation with 1% paraformaldehyde. BAT1-Cy5 cell-targeting assay. Cells were incubated with BAT1-Cy5 for 3 hours (0-10 µM), washed, and analyzed using flow cytometry. Controls. Plerixafor (R&D Systems) pretreatment (20 µM), free Cy5, vehicle (compound-free buffer).

Viability assays.

Doxorubicin was used in a number of the assays and has a broad fluorescence emission profile, which interferes with the use of fluorescent probes for cell death. Therefore, the positions of live, early apoptotic, and dead cells on scatter plots were determined using propidium iodide and annexin-FITC staining (supplemental Figure 8) and were found to be consistent across all cases tested; this confirmed that cell death occurred by an apoptotic, rather than a necrotic, mechanism. Therefore, all viability assays in this study used scatter plots to determine the proportion of dead cells within the population. Measurements of cell viability were performed at 24 hours, which is consistent with the time required for apoptosis to be induced following disruption of the interaction between CLL lymphocytes and supportive cells of monocyte lineage.20,33

Western blot.

Cells were cultured overnight and then exposed to BAT1, plerixafor, or vehicle for 3 hours. Cells were then incubated with 200 ng/mL CXCL12 for 5 minutes at 37°C. Cell pellets were extracted with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (recipe in supplemental Methods and data) before electrophoresis and immunoblotting. Immunoblotting for CXCR4 and CXCR7 was performed without stimulation and used appropriate modifications for tetraspan proteins. Full details are provided in supplemental Methods and data. Visualization used horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody, followed by Amersham ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Amersham, United Kingdom), with a Molecular Imager ChemiDoc XRS+ System (Bio-Rad, Watford, United Kingdom). Image analysis was performed using Image Lab Software (Bio-Rad) and ImageJ (v.1.52a; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Minor changes to image background levels were applied equally to optimize blot visibility in figures.

Messenger RNA analysis.

Results were derived from a wider microarray study on these cells. Briefly, pellets from cells cultured overnight as above were lysed and then RNA was extracted with 100 µL of RLT buffer (Qiagen, Manchester, United Kingdom), yielding 134 ng/mL RNA. Analysis used an Affymetrix 3′ microarray for 20 000 genes (Thermo Fisher) and PUMA 1.2.1 software (University of Manchester).

Immunofluorescence.

Cytospin preparations (Thermo Fisher) of cells, cultured in the presence or absence of drugs, chemokine, or liposomes (as indicated), were mounted and nuclei were visualized using a 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)–containing mountant (ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant; Thermo Fisher) and then examined using an Axio Vert epifluorescent microscope (Zeiss, Cambridge, United Kingdom) or an IX83 inverted microscope (Olympus, Southend-on-Sea, United Kingdom) after antibody staining.

To compare membrane-bound and internal CXCR4 expression, cells in suspension were incubated with mouse anti-CXCR4 on ice (30 minutes), washed, and incubated with an anti-mouse secondary antibody. Samples were then fixed (1% paraformaldehyde) and cytospun onto glass slides before permeabilization (0.1% Triton X-100). A second CXCR4 antibody (rabbit anti-human) with an appropriate secondary antibody was used to visualize internal CXCR4.

Liposome uptake and cargo release were assessed via fluorescence microscopy; decorated and undecorated liposome preparations incorporated 1% (mol/mol) fluorescently labeled PL (TopFluor PC) or doxorubicin (supplemental Methods and data). Cells cultured with decorated or undecorated liposomes were cytospun, fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized, and stained with DAPI. Following acquisition, images were deconvolved using Huygens Software (Scientific Volume Imaging). Z-projection and background correction were performed using ImageJ.

Migration assays.

Cells were cultured overnight, incubated with BAT1, plerixafor, or PBS for 3 hours (concentrations are indicated in the figures), and then aliquoted into the permeable inserts of a filter migration plate (Corning Transwell). The receiving well was filled with complete media (600 µL) containing CXCL12 (200 ng/mL); cells were incubated for 90 minutes at 37°C, and cells from the lower well were counted without further cell purification using a fixed acquisition time with a flow cytometer to provide a cell concentration relative to the positive control (CXCL12, no antagonist).

Doxorubicin-loaded liposome cell death assay.

A method adapted from Iden and Allen34 was used. Cells cultured overnight at 4 × 106 cells per milliliter were dosed with decorated or undecorated doxorubicin-loaded liposomes (dox-liposomes) at 30 to 150 μM (PL), and their viabilities were assessed at 3, 6, and 24 hours. At 3 and 6 hours, cells were washed to remove free liposomes and cultured in fresh media for the remaining 21 or 18 hours, respectively. At 24 hours, all cells were diluted 1:3, and their viability was assessed using flow cytometry. Separate experiments investigating cell death at 3 and 6 hours found that no excess death occurred at these earlier time points (supplemental Figure 9).

Statistical methods

Dose-response curves, aligned dot plots, and cell-migration column charts were plotted and analyzed using Prism (version 7; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). For full equations, see supplemental Methods and data. Statistical analysis used Prism’s in-built analyses (see figure legends). All flow cytometric data were analyzed as median fluorescence intensity using FlowJo software v10. Cell death was normalized with respect to control. Quantification of relative protein expression after western blot was determined via densitometry in Fiji without image adjustment.

Results

Synthetic design of the modified bis(cyclam) drug BAT1

CXCR4 and CXCR7 expression in CLL

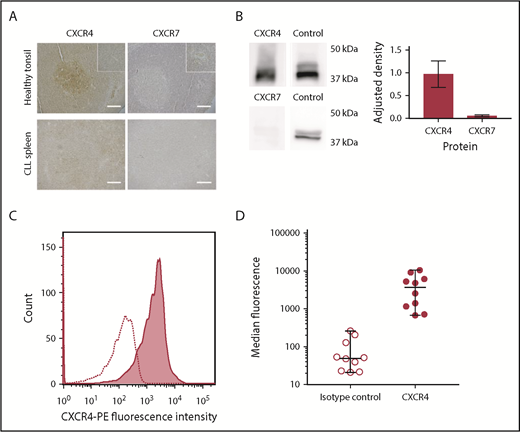

It was previously thought that CXCR4 was the sole receptor for CXCL12, but it has since been found that the scavenger receptor CXCR7 moderates CXCR4 activation by binding and removing CXCL12 from the extracellular milieu.35,36 Bis(cyclam) drugs, such as plerixafor, have been reported to bind to CXCR7, although binding is reported to be weak.37 To understand the role of CXCR4 and CXCR7 during targeting and antagonism with BAT1 and its derivatives in CLL, we analyzed the expression of CXCR4 and CXCR7 by CLL cells and tissues.

Expression of CXCR4 and CXCR7 was demonstrated using immunohistochemistry (IHC). In normal tonsil, both showed the expected patterns of reactivity38 : CXCR4 showed diffuse positivity with particular staining of germinal centers, and CXCR7 stained less strongly but with particular expression in vascular endothelium. In CLL-infiltrated tissue sections, CXCR4 was expressed throughout the tissue, although lower expression was observed in the proliferation centers. Although CXCR7 expression was detected on CLL lymphocytes, this was weak with no significant differences between tissue regions (Figure 2A).

CLL cells consistently express CXCR4 in the peripheral blood and lymphoid organs, whereas CXCR7 expression is significantly lower, (A) Healthy tonsil and CLL spleen sections were stained with antibodies against CXCR4 or CXCR7. In normal tonsil, CXCR4 is widely expressed but with noticeably stronger expression in follicles. In contrast, expression of CXCR7 is weak, and it is expressed primarily by vascular endothelial cells. In organs infiltrated by CLL (shown in spleen), expression of CXCR4 and CXCR7 is observed across the entire sample. CXCR4 staining in proliferation zones is weaker than in other regions of the sample but is still observed. CXCR7 expression is detected, but it is far weaker than CXCR4, with no strong differences observed between proliferation centers and the surrounding tissue. The insets in the upper panels are shown at increased magnification in the lower panels. HRP/DAB technique was used with hematoxylin counterstain. Scale bars, 500 µm. (B) Immunoblot showing relative protein expression levels of CXCR4 and CXCR7 in primary CLL cells, with total ERK1/2 presented as a protein expression control. Densitometric quantification of the blots is shown with adjustment relative to the protein expression control on each blot. Percentage errors were calculated as the average variation between equivalent blots across several experiments. (C) Immunocytofluorescence of CXCR4 assessed by flow cytometry using a phycoerythrin-conjugated CXCR4 antibody for a representative case (shaded graph), with the isotype-control peak shown as a dotted line. (D) Median CXCR4 staining of CLL PBMCs from 10 cases was assessed with flow cytometry using a phycoerythrin-conjugated CXCR4 antibody (●) compared with isotype control (⃝). The median and range of each distribution are represented by horizontal lines. Strong CXCR4 expression is consistently observed, although a significant variation in median staining level was also seen.

CLL cells consistently express CXCR4 in the peripheral blood and lymphoid organs, whereas CXCR7 expression is significantly lower, (A) Healthy tonsil and CLL spleen sections were stained with antibodies against CXCR4 or CXCR7. In normal tonsil, CXCR4 is widely expressed but with noticeably stronger expression in follicles. In contrast, expression of CXCR7 is weak, and it is expressed primarily by vascular endothelial cells. In organs infiltrated by CLL (shown in spleen), expression of CXCR4 and CXCR7 is observed across the entire sample. CXCR4 staining in proliferation zones is weaker than in other regions of the sample but is still observed. CXCR7 expression is detected, but it is far weaker than CXCR4, with no strong differences observed between proliferation centers and the surrounding tissue. The insets in the upper panels are shown at increased magnification in the lower panels. HRP/DAB technique was used with hematoxylin counterstain. Scale bars, 500 µm. (B) Immunoblot showing relative protein expression levels of CXCR4 and CXCR7 in primary CLL cells, with total ERK1/2 presented as a protein expression control. Densitometric quantification of the blots is shown with adjustment relative to the protein expression control on each blot. Percentage errors were calculated as the average variation between equivalent blots across several experiments. (C) Immunocytofluorescence of CXCR4 assessed by flow cytometry using a phycoerythrin-conjugated CXCR4 antibody for a representative case (shaded graph), with the isotype-control peak shown as a dotted line. (D) Median CXCR4 staining of CLL PBMCs from 10 cases was assessed with flow cytometry using a phycoerythrin-conjugated CXCR4 antibody (●) compared with isotype control (⃝). The median and range of each distribution are represented by horizontal lines. Strong CXCR4 expression is consistently observed, although a significant variation in median staining level was also seen.

To confirm these results, microarray analysis and immunoblotting were performed for representative cases. Microarray analysis confirmed the presence of messenger RNA encoding for CXCR7, but the levels of messenger RNA encoding for CXCR4 were 300-fold greater. Western blot analysis showed very high levels of CXCR4, whereas CXCR7 protein levels were very low (Figure 2B). These results are in accordance with previous reports that found low or undetectable levels of CXCR7 on CLL cells.17,39 CXCR4 membrane expression in PBMCs was then investigated in 8 patients using flow cytometry (Figure 2C-D). CLL PBMCs were consistently observed to strongly express CXCR4, but the precise expression levels varied among cases (Figure 2D).

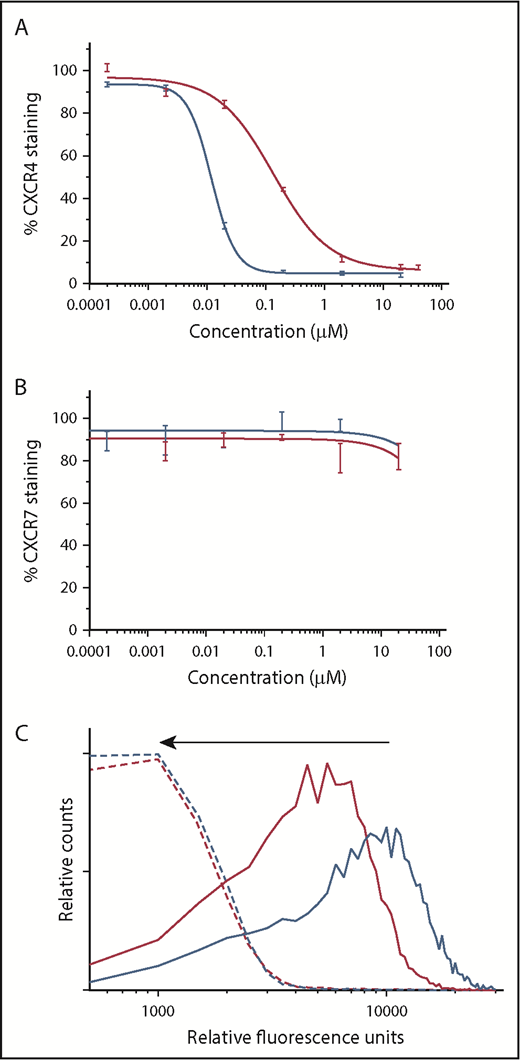

BAT1 binds with high affinity to CXCR4 on primary CLL cells

The binding affinity of BAT1 to CXCR4 or CXCR7 present on primary CLL lymphocytes was assessed by flow cytometry using antibody competition assays.40 In the case of CXCR4, the assay revealed a typical competitive-binding curve similar to the class-leading drug, plerixafor (Figure 3A). The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of BAT1 was found to be 139 ± 3 nM, higher than that of plerixafor (the measured IC50 for plerixafor in this assay was 11.7 ± 0.7 nM, and the published IC50 is 44 nM41 ). However, the binding affinity of BAT1 compares favorably with similarly modified molecules within the bis(cyclam) class,42,43 with the IC50 and IC90 values of BAT1 well within the reported achievable plasma levels for plerixafor (achievable and safe plasma concentration 800-1000 ng/mL equivalent to 2 μM44 ). When the same assay approach was used to assess binding to CXCR7, neither plerixafor nor BAT1 caused a significant reduction in antibody attachment to the cells, suggesting that CXCR4 is the major receptor through which plerixafor and BAT1 act in primary CLL cells. This observation is in agreement with the very low expression of CXCR7, and with previous reports in which plerixafor binding to CXCR7 was only observed at very high concentrations (>10 μM).37

BAT1 binds tightly to CXCR4, leading to dose-dependent inhibition of antibody binding and delivery of fluorescent cargo. (A) Phycoerythrin-CXCR4 antibody competition assay against BAT1 (red line) and plerixafor (blue line), assessed using flow cytometry. Primary CLL cells from a representative case were incubated with BAT1 or plerixafor at concentrations between 0 and 20 µM for 3 hours and then stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated CXCR4 antibodies. Experiment was performed in triplicate, and the mean was taken of the medians of each fluorescent distribution; errors were calculated as standard deviation of the mean. Dose-response curve fitted using a modified Hill equation, as detailed in supplemental Methods and data. A dose-dependent reduction in fluorescence was observed for BAT1 and plerixafor, with IC50(BAT1) = 138 nM and IC50(plerixafor) = 11.7 nM. (B) Analogous PerCP-CXCR7 antibody competition assay against BAT1 (red line) and plerixafor (black line). A dose-dependent reduction in antibody-staining was not observed for BAT1 or plerixafor. Fluorescence due to bound anti-CXCR7 antibody decreased at the highest concentrations of plerixafor or BAT1, but this decrease is within the measurement error, determined using the standard deviation of the mean. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of dose-dependent and selective BAT1-Cy5 targeting to CLL cells. Primary CLL cells were incubated with Cy5-conjugated BAT1 at 5 µM (solid red line) and 10 µM (solid blue line) for 3 hours. To demonstrate selectivity, the cells were also preincubated with 20 µM plerixafor as a comparison (dashed lines). BAT1-Cy5 was found to bind to CLL cells in a dose-dependent manner, and cells preincubated with 20 µM plerixafor present significantly reduced fluorescence, as indicated by the arrow. These data indicate that BAT1 can be used to specifically target functional molecules, such as dyes, to CXCR4-expressing cells.

BAT1 binds tightly to CXCR4, leading to dose-dependent inhibition of antibody binding and delivery of fluorescent cargo. (A) Phycoerythrin-CXCR4 antibody competition assay against BAT1 (red line) and plerixafor (blue line), assessed using flow cytometry. Primary CLL cells from a representative case were incubated with BAT1 or plerixafor at concentrations between 0 and 20 µM for 3 hours and then stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated CXCR4 antibodies. Experiment was performed in triplicate, and the mean was taken of the medians of each fluorescent distribution; errors were calculated as standard deviation of the mean. Dose-response curve fitted using a modified Hill equation, as detailed in supplemental Methods and data. A dose-dependent reduction in fluorescence was observed for BAT1 and plerixafor, with IC50(BAT1) = 138 nM and IC50(plerixafor) = 11.7 nM. (B) Analogous PerCP-CXCR7 antibody competition assay against BAT1 (red line) and plerixafor (black line). A dose-dependent reduction in antibody-staining was not observed for BAT1 or plerixafor. Fluorescence due to bound anti-CXCR7 antibody decreased at the highest concentrations of plerixafor or BAT1, but this decrease is within the measurement error, determined using the standard deviation of the mean. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of dose-dependent and selective BAT1-Cy5 targeting to CLL cells. Primary CLL cells were incubated with Cy5-conjugated BAT1 at 5 µM (solid red line) and 10 µM (solid blue line) for 3 hours. To demonstrate selectivity, the cells were also preincubated with 20 µM plerixafor as a comparison (dashed lines). BAT1-Cy5 was found to bind to CLL cells in a dose-dependent manner, and cells preincubated with 20 µM plerixafor present significantly reduced fluorescence, as indicated by the arrow. These data indicate that BAT1 can be used to specifically target functional molecules, such as dyes, to CXCR4-expressing cells.

To demonstrate direct targeting of BAT1 to CLL cells, the BAT1-Cy5 conjugate was incubated with the cells, and cellular fluorescence was assessed using flow cytometry. BAT1-Cy5 showed high affinity for CXCR4-expressing CLL lymphocytes, and specificity was confirmed by inhibition of BAT1-Cy5 binding following incubation of cells with plerixafor (Figure 3B-C).

BAT1 functions as a CXCL12 antagonist in primary CLL lymphocytes

Drugs of the bis(cyclam) class are reported to act as pure antagonists that prevent binding of CXCL12 to CXCR4 but are not internalized and do not display agonist function.45 Functional assays were used to confirm that these attributes were retained by BAT1.

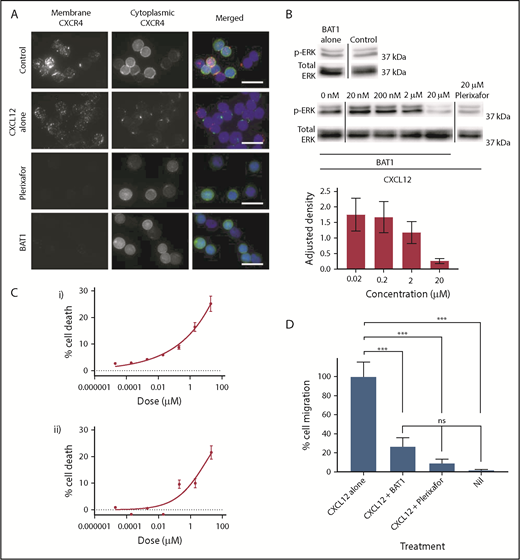

First, cytoplasmic and membrane distributions of CXCR4 were compared using a dual (surface and internal) immunostaining approach (Figure 4A), which confirmed that CXCR4 was present across the cell membrane and in the cytoplasm of untreated CLL lymphocytes. Treatment with CXCL12 led to cell surface CXCR4 expression becoming reduced and punctate, with redistribution of the cytoplasmic fraction to a focal region (Figure 4A, second row). In contrast, incubation with plerixafor or BAT1 completely blocked staining of the membrane by anti-CXCR4, confirming that BAT1 binds tightly to CXCR4. Cytoplasmic expression and distribution were unaffected following exposure to BAT1 or plerixafor, suggesting that neither drug was internalized.

BAT1 acts as a pure antagonist against CXCL12, reducing migration along the chemokine gradient and cell viability in vitro. (A) Fluorescence microscopy analysis of receptor redistribution following exposure to CXCL12, BAT1, or plerixafor. Primary CLL cells were incubated with vehicle, 20 µM BAT1, or 20 µM plerixafor for 3 hours before exposure to CXCL12 for 10 minutes. Control cells were incubated with vehicle alone (no CXCL12). Cells were then stained for membrane and cytoplasmic CXCR4 to assess its distribution. Unstimulated CLL lymphocytes (top row) express CXCR4 at the cell surface and in the cytoplasm. Binding of CXCL12 causes receptor internalization with intracellular redistribution, with possible trafficking of cytoplasmic CXCR4 to the membrane (second row). Plerixafor (third row) and BAT1 (bottom row) bind to surface CXCR4, blocking immunoreactivity, but they do not induce receptor internalization or redistribution. Original magnification ×600 (60× 1.4 N.A. objective lens). Scale bars, 20 µm. (B) Immunoblotting demonstrates BAT1’s antagonism of CXCL12-induced signaling. Primary CLL cells were incubated with BAT1, plerixafor, or vehicle for 3 hours before exposure to CXCL12 for 10 minutes. Lysates were prepared, and signaling levels were assessed by immunoblotting for ERK phosphorylation (p-ERK). Incubation with BAT1 led to a dose-dependent reduction in p-ERK, with saturating levels of BAT1 reducing p-ERK to similar levels as 20 µM plerixafor or no stimulation. Densitometric quantification of the blots is shown with adjustment relative to total ERK for each lane. Percentage errors were calculated based on the average variation between equivalent blots across several experiments. (C) Effects of BAT1 and plerixafor on cell viability were assessed over 24 hours using flow cytometry. Primary CLL cells were incubated with plerixafor (i) or BAT1 (ii) at a range of concentrations over 24 hours. A progressive decrease in cellular viability was demonstrated at concentrations exceeding 20 nM BAT1 or plerixafor. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and the mean was taken. Errors are the standard deviation of the mean, added in quadrature to the standard error on the gating. Curves were fitted using nonlinear regression with software’s in-built log(agonist) vs response curve with variable slope, based on the Hill equation. (D) Inhibition of chemotaxis in response to CXCL12 was assessed using a filter migration assay, where cell migration was assessed using flow cytometry. BAT1 significantly reduces chemotactic migration of CLL lymphocytes. No significant difference in migration levels was seen between the BAT1-treated cells and those treated with plerixafor or vehicle alone. ***P < .001, 1-way analysis of variance with the Holm-Sidak multiple-comparisons test. ns, not significant.

BAT1 acts as a pure antagonist against CXCL12, reducing migration along the chemokine gradient and cell viability in vitro. (A) Fluorescence microscopy analysis of receptor redistribution following exposure to CXCL12, BAT1, or plerixafor. Primary CLL cells were incubated with vehicle, 20 µM BAT1, or 20 µM plerixafor for 3 hours before exposure to CXCL12 for 10 minutes. Control cells were incubated with vehicle alone (no CXCL12). Cells were then stained for membrane and cytoplasmic CXCR4 to assess its distribution. Unstimulated CLL lymphocytes (top row) express CXCR4 at the cell surface and in the cytoplasm. Binding of CXCL12 causes receptor internalization with intracellular redistribution, with possible trafficking of cytoplasmic CXCR4 to the membrane (second row). Plerixafor (third row) and BAT1 (bottom row) bind to surface CXCR4, blocking immunoreactivity, but they do not induce receptor internalization or redistribution. Original magnification ×600 (60× 1.4 N.A. objective lens). Scale bars, 20 µm. (B) Immunoblotting demonstrates BAT1’s antagonism of CXCL12-induced signaling. Primary CLL cells were incubated with BAT1, plerixafor, or vehicle for 3 hours before exposure to CXCL12 for 10 minutes. Lysates were prepared, and signaling levels were assessed by immunoblotting for ERK phosphorylation (p-ERK). Incubation with BAT1 led to a dose-dependent reduction in p-ERK, with saturating levels of BAT1 reducing p-ERK to similar levels as 20 µM plerixafor or no stimulation. Densitometric quantification of the blots is shown with adjustment relative to total ERK for each lane. Percentage errors were calculated based on the average variation between equivalent blots across several experiments. (C) Effects of BAT1 and plerixafor on cell viability were assessed over 24 hours using flow cytometry. Primary CLL cells were incubated with plerixafor (i) or BAT1 (ii) at a range of concentrations over 24 hours. A progressive decrease in cellular viability was demonstrated at concentrations exceeding 20 nM BAT1 or plerixafor. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and the mean was taken. Errors are the standard deviation of the mean, added in quadrature to the standard error on the gating. Curves were fitted using nonlinear regression with software’s in-built log(agonist) vs response curve with variable slope, based on the Hill equation. (D) Inhibition of chemotaxis in response to CXCL12 was assessed using a filter migration assay, where cell migration was assessed using flow cytometry. BAT1 significantly reduces chemotactic migration of CLL lymphocytes. No significant difference in migration levels was seen between the BAT1-treated cells and those treated with plerixafor or vehicle alone. ***P < .001, 1-way analysis of variance with the Holm-Sidak multiple-comparisons test. ns, not significant.

Western blotting was used to confirm that CXCL12-induced signaling was prevented by BAT1 (Figure 4B). At saturating levels of BAT1 (20 μM; saturation confirmed by an antibody competition assay, see Figure 3A), immunoblotting analysis confirmed complete inhibition of CXCL12-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation: phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in the presence of BAT1 and CXCL12 was comparable to that in the absence of CXCL12 or following plerixafor antagonism at saturating concentrations (Figure 4C). In a filter-migration assay, >70% reduction in chemotaxis was observed at saturating doses of BAT1 or plerixafor, equivalent to migration in the absence of CXCL12 (Figure 4D). In addition, it was found that BAT1 reduced the viability of CLL lymphocytes at doses associated with significant receptor blockade (>90% receptor occupancy), equivalent to the levels observed with plerixafor (Figure 4B). We suggest that this is likely to be caused by disrupting the interactions between CLL lymphocytes and the supportive monocytes present in their culture.20,33

Together, these findings show that, in addition to CXCR4-targeting activity, BAT1 antagonizes intracellular signal generation, cell migration, and prosurvival effects of CXCL12. Importantly, we did not identify any additional toxicity attributable to the modified structure of the drug compared with plerixafor.

BAT1-liposomes bind to CLL lymphocytes with high affinity and retain CXCL12-blocking function

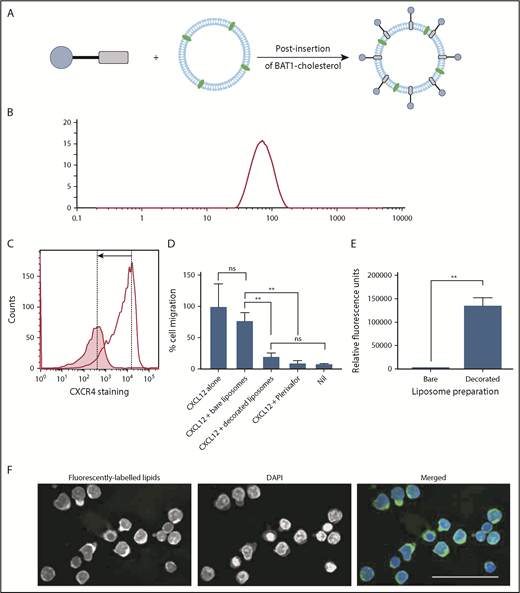

Liposomes were prepared incorporating a fluorescently labeled lipid (Figure 1B) to allow tracking. Fluorescent liposomes were decorated with BAT1-cholesterol using a postinsertion technique34 (Figure 5A).

BAT1-cholesterol can be used to decorate fluorescently labeled liposomes, resulting in significantly higher uptake into cells. (A) Illustration of the prepared liposomes, indicating BAT1-cholesterol decoration of the fluorescently labeled liposomal membrane using the postinsertion method. (B) Liposome sizes were assessed using DLS. A representative line graph from the analysis is shown: intensity is related to particle size using the Mie scattering function. (C) CXCR4 antibody staining was used to assess the specificity of liposome binding. Cells were stained with phycoerythrin-CXCR4 antibodies following incubation with bare liposomes (black line) or BAT1-decorated liposomes (filled graph). In the presence of bare liposomes, ∼94% of the live cells are stained to a high level. In the presence of BAT1-labeled liposomes, ∼37% of cells are stained, and the median fluorescence is significantly lower. Cell staining reduction is indicated by the arrow. (D) Cell migration in response to CXCL12 was measured using a filter migration assay. Data shown are from 1 representative case. Experiments were performed in triplicate, means were taken across the triplicates, and errors were calculated as the standard deviation of the mean. BAT1-decorated liposomes inhibit migration along a CXCL12 gradient: no significant difference in migration inhibition is observed between BAT1-decorated liposomes and 20 μM plerixafor or the negative control. Further, no significant difference in migration was observed between cells incubated with bare liposomes and the positive control. **P < .01, 1-way analysis of variance with the Holm-Sidak multiple-comparisons test. (E) Flow cytometry was used to quantify levels of liposomal attachment and uptake. At only 30 µM liposomes, the cells incubated with decorated liposomes presented significantly higher levels of fluorescence (**P < .01, Student t test). (F) Laser deconvolution microscopy was used to show in which region of the cell the liposomes are located after a 3-hour incubation. Liposomes fluoresce in green, whereas nuclei are labeled with DAPI (blue). Images were prepared by building a z-projection (median intensity) from the image stack comprising the central region of the cell. The liposomes are observed throughout the cytoplasm. Scale bar, 50 µm.

BAT1-cholesterol can be used to decorate fluorescently labeled liposomes, resulting in significantly higher uptake into cells. (A) Illustration of the prepared liposomes, indicating BAT1-cholesterol decoration of the fluorescently labeled liposomal membrane using the postinsertion method. (B) Liposome sizes were assessed using DLS. A representative line graph from the analysis is shown: intensity is related to particle size using the Mie scattering function. (C) CXCR4 antibody staining was used to assess the specificity of liposome binding. Cells were stained with phycoerythrin-CXCR4 antibodies following incubation with bare liposomes (black line) or BAT1-decorated liposomes (filled graph). In the presence of bare liposomes, ∼94% of the live cells are stained to a high level. In the presence of BAT1-labeled liposomes, ∼37% of cells are stained, and the median fluorescence is significantly lower. Cell staining reduction is indicated by the arrow. (D) Cell migration in response to CXCL12 was measured using a filter migration assay. Data shown are from 1 representative case. Experiments were performed in triplicate, means were taken across the triplicates, and errors were calculated as the standard deviation of the mean. BAT1-decorated liposomes inhibit migration along a CXCL12 gradient: no significant difference in migration inhibition is observed between BAT1-decorated liposomes and 20 μM plerixafor or the negative control. Further, no significant difference in migration was observed between cells incubated with bare liposomes and the positive control. **P < .01, 1-way analysis of variance with the Holm-Sidak multiple-comparisons test. (E) Flow cytometry was used to quantify levels of liposomal attachment and uptake. At only 30 µM liposomes, the cells incubated with decorated liposomes presented significantly higher levels of fluorescence (**P < .01, Student t test). (F) Laser deconvolution microscopy was used to show in which region of the cell the liposomes are located after a 3-hour incubation. Liposomes fluoresce in green, whereas nuclei are labeled with DAPI (blue). Images were prepared by building a z-projection (median intensity) from the image stack comprising the central region of the cell. The liposomes are observed throughout the cytoplasm. Scale bar, 50 µm.

Various lipid formulations were assessed for their stability and targeting ability: DOPC (a PL commonly used in liposomes) was used alone or in combination with 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine or 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol), both of which are more strongly negatively charged. The different lipid formulations were assessed because BAT1 is cationic, and the increase in liposome surface charge following its insertion could affect the stability of the liposome suspension. DLS confirmed that all liposome preparations had hydrodynamic radii in the range of 119 to 137 nm (Figure 5B). Successful insertion of BAT1-cholesterol into the liposomal membrane was supported by observed changes in the ζ potential of the liposomes, which gives an indication of the surface charge. After incubation with BAT1-cholesterol, the ζ potential of every formulation increased significantly (eg, DOPC liposomes became more positive by 23.2 ± 1.5 mV, consistent with successful insertion of BAT1-cholesterol).

CXCR4 specificity of BAT1-decorated liposomes was assessed with primary CLL lymphocytes. Antibody staining of CXCR4 was significantly reduced following cell incubation with BAT1-decorated liposomes in comparison with undecorated liposomes (Figure 5C). Furthermore, when cellular migration in response to CXCL12 was tested in the presence or absence of BAT1-decorated liposomes, it was found that insertion of BAT1-cholesterol into liposomes did not diminish the function-blocking activity of BAT1 (Figure 5D). Indeed, BAT1-liposomes showed a similar level of function-blocking activity as plerixafor, reducing migration to the level observed in the absence of CXCL12. In addition, BAT1-DOPC liposomes retained their biological effects for up to 4 weeks.

Liposomes were incubated for 3 hours with primary CLL cells at PL concentrations between 30 and 300 µM, and uptake was assessed using flow cytometry. All 3 of the BAT1-labeled fluorescent liposome preparations were preferentially taken up compared with bare liposomes of the same lipid composition (supplemental Figure 4). BAT1-DOPC liposomes showed the greatest uptake, with significantly higher fluorescence observed, even at 30 µM PL. This result was replicated after a 24-hour coculture with CD40L murine fibroblasts, which reduce CXCR4 membrane expression (Figure 5E; supplemental Figures 5 and 6). Laser deconvolution microscopy images showed TopFluor fluorescence present throughout the cell cytoplasm, consistent with liposome uptake rather than cell membrane binding (Figure 5F).

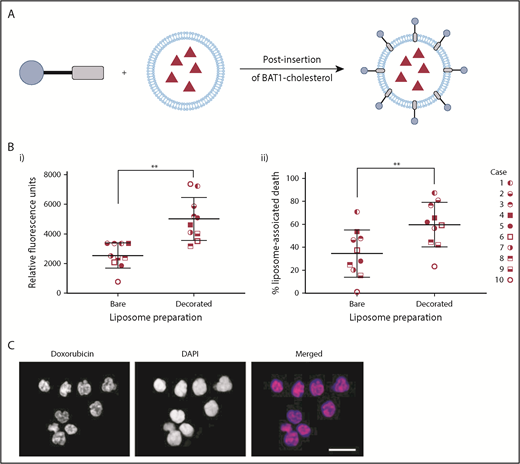

BAT1-liposomes deliver high levels of doxorubicin and greater levels of cytotoxicity

Doxorubicin was chosen as a model drug for liposomal encapsulation and delivery. Successful BAT1-cholesterol insertion into dox-liposomes was supported by changes in their ζ potential. In HEPES buffer, the ζ potential of the bare liposomes was measured to be −2.8 ± 1.4 mV, which increased to 24.1 ± 1.3 mV following the addition of cationic BAT1-cholesterol. Liposomal concentrations from 30 to 300 μM (PL) and time points ranging from 3 to 24 hours were initially assessed using a representative CLL case. Cell death was assessed at 24 hours to allow sufficient time for the effects of the doxorubicin to become apparent; for the earlier incubation time points, cells were washed to remove liposomes that had not been taken up. These initial assays showed that incubation with 75 μM liposomes for only 3 hours led to a significant difference in cell death between BAT1-labeled liposomes and their bare counterparts; therefore, these conditions were used in subsequent cell death assays.

Liposomal uptake and cell death were assessed in 10 separate cases to ensure the robustness and reproducibility of the results and to control for the variability in levels of CXCR4 expression (Figure 2D). Flow cytometric analysis confirmed that BAT1-liposomes delivered significantly higher quantities of doxorubicin, with approximately twofold greater doxorubicin-associated fluorescence in cells that had died after treatment with BAT1-labeled liposomes compared with bare liposomes (Figure 6Bi). Furthermore, BAT1-decorated liposomes consistently led to increased cell death across the sample set (Figure 6Bii), with the increase in median cell death from BAT1-liposomes approximately double that of bare doxorubicin liposome controls. Fluorescence microscopy was used to investigate the region to which the doxorubicin had been delivered: at only 3 hours, DAPI and doxorubicin fluorescence colocalization implied that doxorubicin had been delivered to the nucleus (Figure 6C).

BAT1 decoration of dox-liposomes leads to increased uptake in primary CLL cells, causing significantly increased rates of death compared with bare liposomes. (A) Schematic illustrating the postinsertion process for decorating dox-liposomes. (B) Primary CLL cells from 10 subjects were incubated with dox-liposomes, with and without BAT1 decoration. (Bi) Liposomal uptake and doxorubicin delivery were determined by assessing the doxorubicin-associated fluorescence in dead cells using flow cytometry. Each point represents the median fluorescence from an individual case. Median doxorubicin-associated fluorescence in dead CLL cells is significantly higher when CLL cells are incubated with BAT1-decorated dox-liposomes than with bare dox-liposomes. P = .0020, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. (Bii) Dox-liposome–associated death was measured in primary CLL cells across 10 cases using flow cytometry. The number of dead cells was calculated using forward/side scatter. BAT1-decorated liposomes consistently led to increased levels of cell death across all cases tested. P = .0039, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test (**P < .01). (C) Cellular localization of the doxorubicin was assessed using laser deconvolution microscopy. Images were prepared by building a z-projection (intensity sum) from the image stack comprising the central region of the cell. Colocalization of the doxorubicin-associated red fluorescence and the DAPI staining was used as a measure of delivery to the cell nucleus. Doxorubicin is delivered to the cell nucleus in large quantities when cells are incubated for 3 hours with BAT1-decorated liposomes. Scale bar, 20 µm.

BAT1 decoration of dox-liposomes leads to increased uptake in primary CLL cells, causing significantly increased rates of death compared with bare liposomes. (A) Schematic illustrating the postinsertion process for decorating dox-liposomes. (B) Primary CLL cells from 10 subjects were incubated with dox-liposomes, with and without BAT1 decoration. (Bi) Liposomal uptake and doxorubicin delivery were determined by assessing the doxorubicin-associated fluorescence in dead cells using flow cytometry. Each point represents the median fluorescence from an individual case. Median doxorubicin-associated fluorescence in dead CLL cells is significantly higher when CLL cells are incubated with BAT1-decorated dox-liposomes than with bare dox-liposomes. P = .0020, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. (Bii) Dox-liposome–associated death was measured in primary CLL cells across 10 cases using flow cytometry. The number of dead cells was calculated using forward/side scatter. BAT1-decorated liposomes consistently led to increased levels of cell death across all cases tested. P = .0039, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test (**P < .01). (C) Cellular localization of the doxorubicin was assessed using laser deconvolution microscopy. Images were prepared by building a z-projection (intensity sum) from the image stack comprising the central region of the cell. Colocalization of the doxorubicin-associated red fluorescence and the DAPI staining was used as a measure of delivery to the cell nucleus. Doxorubicin is delivered to the cell nucleus in large quantities when cells are incubated for 3 hours with BAT1-decorated liposomes. Scale bar, 20 µm.

Discussion

We have developed a novel drug-delivery system, BAT1-liposome, and showed that it binds with high specificity and affinity to CXCR4. This allows targeted delivery of therapeutics to CLL cells and blocks their interaction with the chemoprotective chemokine CXCL12. When used to deliver doxorubicin, BAT1-liposomes consistently increased CLL cell death compared with undecorated liposomes. The combination of targeted drug delivery and receptor blockade provided by BAT1-liposomes is highly attractive in hematology; it has the potential to deliver an increased local dose of therapeutics while disrupting the cancer cells’ interaction with their chemoprotective niche.

Clinical relevance, versatility, and modularity were central to the design of BAT1 and its application in liposomal drug delivery. The use of CXCR4-targeted drug delivery utilizing a bis(cyclam) motif has been tested by other investigators: in particular, Oupický and colleagues developed a range of bis(cyclam)-based polymers (polymeric-plerixafor) for drug delivery that display CXCR4 antagonism and are taken up preferentially by CXCR4-overexpressing cells.26-28,46,47 However, the use of polymeric-plerixafor as the drug-delivery system introduces some constraints: a balance of CXCR4 affinity, binding of therapeutic agents, and pharmacological behavior within the body must all be sought from the same material. In contrast, BAT1 is readily conjugated to fluorescent moieties or cholesterol for insertion into liposomes, and it retains high efficacy in CXCR4 targeting and antagonism, demonstrating the versatility of the design approach. Liposomes were selected because they are the most well-developed drug-delivery system and are already widely used in clinical practice2,48 ; in addition they have been used to encapsulate or complex a wide range of therapeutics, from small-molecule drugs to biomolecules.49-52 Doxorubicin is an excellent model drug because it is used extensively in the clinic for cancer treatment in its free and liposomal forms, and it is inherently fluorescent. However, we believe that BAT1-liposomes are applicable to a wide range of cargo, the choice of which could be used to strengthen or tailor the system to its application.

Although the cancer model used in this paper is CLL, the methodology described should be applicable to a broad range of hematological cancers in which CXCR4 is overexpressed. Hematological cancer treatments are limited by the dose that can be delivered to cancer cells while avoiding bystander cell toxicity. This can be associated with persistent measurable residual disease, leading to treatment resistance and disease reemergence.14,33,53,54 Liposomes have the capability to deliver therapeutics at far higher effective concentrations than would be possible with systemic delivery. Furthermore, the biology of hematological cancers means that they are particularly strong targets for liposomal-targeted drug delivery: liposomes will encounter neoplastic cells during circulation, and fenestrations in the bone marrow and lymphoid vasculature allow liposomal extravasation and accumulation in the regions of interest.55-57 The function-blocking properties of BAT1-liposomes also mean that cancer cells may be retained in the circulation, blocked from the CXCL12 gradient that promotes their movement into the chemoprotective niche and potentially leading to additional sensitivity to treatment. The use of drug-delivery systems, such as liposomes, provides unique advantages for the treatment of hematological disorders, such as CLL, because unlike small-molecule drugs that must pass through the cell membrane, liposomes can exploit active uptake through mechanisms such as macropinocytosis, which is used readily by mature immune cells.58-61

The BAT1-liposome system was designed to incorporate 2 important properties: targeted therapeutic delivery to CXCR4-overexpressing cells and antagonism against CXCL12, both of which have now been demonstrated. This dual mechanism differentiates BAT1-liposomes from other targeted drug-delivery systems that increase selective uptake of a therapeutic agent but do not have a therapeutic action themselves.7,8 BAT1 tight binding to CXCR4 was demonstrated alone and following conjugation to liposomes. Although the receptor redistribution assay demonstrated that BAT1 alone was a pure antagonist without evidence of uptake, microscopy showed that BAT1-liposomes were taken up into the cell. This is in accordance with the literature, because liposomes and other nanoparticles within the 150 to 200–nm size range are expected to be endocytosed by lymphocytes through nonreceptor-mediated routes.59-61 Doxorubicin delivered by liposomes was observed in the cell nuclei, and BAT1-targeted dox-liposomes caused significantly higher levels of cell death across 10 cases expressing various levels of CXCR4. These results were despite the fact that neither BAT1-liposomes nor undecorated (bare) liposomes were stealth coated, which would be expected to reduce nonspecific uptake.48 Compared with free doxorubicin at an equivalent concentration, BAT1-liposomes led to increased cell death (supplemental Figure 10). Furthermore, although free doxorubicin still produced high levels of cell death, the free drug cannot show the same selectivity for specific cell types observed for BAT1-liposomes. In addition to therapeutics delivery, BAT1-liposomes retained their antagonistic properties: functional blocking was shown in the inhibition of cellular migration along a CXCL12 gradient. This demonstrates that BAT1-liposomes may be able to target CXCR4-overexpressing cells and disrupt their interactions with the chemoprotective niche, thereby sensitizing them to treatment. In future work, stealth coating could be used to extend the in vivo circulation time of BAT1-liposomes. Furthermore, the encapsulation of signal inhibitors or nucleic acids would combine their strengths with those of the BAT1-liposome system: protecting sensitive cargo from degradation, allowing higher effective concentrations to be delivered, and reducing bystander toxicity.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rehana Sung for guidance in developing high-performance liquid chromatography protocols and the Manchester University School of Chemistry's Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Service; Reynard Spiess and the Mass Spectrometry Service (School of Chemistry, University of Manchester) for mass spectrometry support; Steve Marsden and Peter March (Bioimaging Facility, in the Michael Smith Building, University of Manchester) for microscopy guidance; Richard Byers and Marcus Price for providing samples for IHC and training in IHC, respectively; and Robin Curtis and the Curtis group for the kind use of the Malvern Zetasizer.

This work was supported by a University of Manchester Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) Doctoral Prize Award (grant EP/N509565/1), an EPSRC NOWNANO Doctoral Training Centre studentship (grant EP/G03737X/1), the Manchester Pharmacy School (University of Manchester), the Horace Hayhurst Memorial Trust, and a Colloid Science studentship from the School of Chemistry (University of Manchester).

Authorship

Contribution: C.M. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed data, designed the figures, and wrote the manuscript; A.D.P. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and reviewed the manuscript; A.B. designed experiments and assisted in their performance and reviewed the manuscript; K.R.-U. and J.A. assisted with the design and performance of experiments and reviewed the manuscript; R.R. performed experiments, analyzed data, and reviewed the manuscript; A.P. assisted in the research design and reviewed the manuscript; C.V.H. provided and characterized patient samples, performed experiments, and reviewed the manuscript; S.J.W. designed the research (chemistry lead) and wrote the manuscript; and J.B. designed the research (biology lead) and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for A.B. is School of Chemistry, University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom.

Correspondence: John Burthem, Division of Cancer Sciences, School of Medical Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester M20 4GJ, United Kingdom; e-mail: john.burthem@mft.nhs.uk.

References

Author notes

For original data, please contact John Burthem (john.burthem@mft.nhs.uk).