Key Points

TXA is an active-site inhibitor of uPA.

TXA attenuates MDA-MB-231 BAG cell migration and inhibits endogenous uPA activity.

Introduction

Lysine binding sites (LBSs) of plasminogen (Plg) are essential for maintaining a closed conformation in circulation and binding to fibrin and cell surface receptors.1,2 Upon binding to the targets, Plg is activated to plasmin (Plm) by the fibrin-bound tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) or the cell receptor–bound urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA). Tranexamic acid (TXA) is a lysine analog that binds to the LBSs of Plg with 1 high-affinity (1.1 μM) and 3 medium-affinity (∼0.75 mM) binding sites.1-3 Accordingly, TXA at submicromolar concentrations significantly attenuates in situ Plm formation4 and is used frequently as an antifibrinolytic agent in trauma, as well as in major surgeries, including cardiac, orthopedic, and hepatic surgeries.5

The CRASH-26 and MATTERs7 clinical studies revealed that, when TXA is administered within 3 hours after injury, mortality is reduced by up to 20%.8 Recent reanalysis of the clinical data further showed that the survival benefit of TXA decreased by 10% for every 15 minutes of delayed administration, with no benefit obtained after 3 hours.9 This lack of efficacy outside of the “3-hour window” has been associated with the upregulation of plasma uPA postinjury.6,10,11

We have previously observed that a very high concentration (∼25 mM) of TXA inhibits Plm activity via binding to the primary catalytic (S1) pocket of the enzyme.12 However, because of the low affinity of TXA for Plm, we do not anticipate that TXA functions as a Plm inhibitor during clinical use.12 However, given these findings, we investigated whether TXA may have an inhibitory effect on other proteases in the Plg-activation system. Unexpectedly, our results revealed that TXA attenuates uPA activity with an inhibitory constant (Ki) of 2 mM. In contrast, similar efficacy is not observed in the presence of ε-aminocaproic acid (EACA; an alternative drug to TXA).

Methods

Detailed methods are as described in the figure legends.

Protein Data Bank accession code

The atomic coordinates and structure factors of the uPA–TXA complex reported here have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under code 6NMB.

UniProt IDs

The UniProt IDs of serine proteases used in this study are listed in parentheses: human Plg (P00747, residue 20-810), full-length uPA or urokinase (P00749, residue 21-431), full-length tPA (P00750, residue 36-562), and the serine protease domain of plasma kallikrein (P03952, residue 381-638).

Results and discussion

We tested the ability of TXA to inhibit plasma kallikrein, uPA, and tPA (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1; supplemental Table 1). The data reveal that uPA is most susceptible to TXA inhibition (Ki, 2.01 ± 0.09 mM; half-maximal inhibitory concentration [IC50], 3.63 ± 0.16 mM) in comparison with Plm (IC50, 86.79 ± 2.30 mM),12 plasma kallikrein (IC50, 67.53 ± 2.69 mM), and tPA (not determined). By comparison, the inhibition of uPA activity by EACA is approximately sixfold lower (IC50, 25.25 ± 1.50 mM).

TXA is an active site inhibitor of uPA. (A) The residual enzyme activity of tPA (Actilyse; Boehringer Ingelheim), Plm (Haematologic Technologies), plasma kallikrein (KLK; residue 381-638 recombinantly expressed and purified from Expi293 cells),12 and uPA (urokinase medac) was measured in the presence of TXA and EACA (0-125 mM) in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, and 0.01% Tween-80 at 450 nm, as previously described.21 IC50 derived from the linear absorbance range and Ki are summarized in supplemental Table 1. The Michaelis-Menten constant (Km) and the apparent Km values for uPA in the presence of 0 to 15 mM TXA were also determined with 0 to 0.5 mM S-2444, and data were plotted using GraphPad Prism 7.0 to calculate Ki (supplemental Figure 1; supplemental Table 1). (B) The residual clot lysis activity (reciprocal plot of the normalized 50% clot lysis time in supplemental Figure 4) was recorded in the presence of 1 μM Plm, 1 μM Plg plus tPA, or 1 μM Plg plus uPA at the concentrations indicated. Each reaction consists of a 100-μL fibrin clot preformed by incubating human fibrinogen (12.5 μM; Enzyme Research Laboratories) and thrombin (55 nM; Diagnostic Reagents) in a lysis buffer (40 mM Tris, 75 mM NaCl, 3 mM CaCl2, 0.01% Tween-20) at 37°C for 3 hours. An additional 100 μL of lysis buffer containing Plm or Plg plus tPA/uPA in the presence of 0 to 25 mM TXA was added to start the lysis; the progress of clot lysis was monitored using a nephelometer (BMG LABTECH), which records every minute for 5.5 hours at 37°C. Fifty percent clot lysis time was determined using an online application (https://drclongstaff.shinyapps.io/clotlysisCL/).22 (C) During fibrin clot lysis, Plm and uPA enzyme activities were also measured in the presence of TXA (0-50 mM), Plm substrate (H-Ala-Phe-Lys-AMC; Bachem), or uPA substrate (Glutaryl-Gly-Arg-AMC; Sekisui Diagnostics) in 100 μL of lysis buffer, as described in panel B. Enzyme activity was recorded using a FLUOstar Omega (BMG) at 37°C; excitation and emission were 355 nm and 460 nm, respectively. All data points represent the mean ± standard deviation of a minimum of 3 independent experiments. (D) Cocrystal structure of uPA and TXA. uPASP (serine protease domain of human uPA, residue 164-431) was expressed and purified from Expi293 cells, as previously described.12 uPASP was activated to the 2-chain form (tc-uPASP) by Plm (Haematologic Technologies), concentrated to 10 mg/mL, and mixed with 20 mM TXA for crystallization trials. Crystals were obtained in the presence of 0.03 M NaNO3, 0.03 M Na2HPO4, 0.03 M (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 M Tris-bicine pH 8.5, 25% (weight-to-volume ratio) polyethylene glycol monomethyl ether 500, and 10% (weight-to-volume ratio) polyethylene glycol 20 000 at 20°C. The electrostatic surface representation of uPA (basic, blue; acidic, red) is shown, with key binding residues (cyan sticks) to TXA (green sticks) labeled. There are 4 binary complex molecules in the asymmetric unit, and the model of monomer A with TXA is shown. Data collection and processing were performed as previously described (supplemental Table 2).12 Further information is shown in supplemental Figure 5.

TXA is an active site inhibitor of uPA. (A) The residual enzyme activity of tPA (Actilyse; Boehringer Ingelheim), Plm (Haematologic Technologies), plasma kallikrein (KLK; residue 381-638 recombinantly expressed and purified from Expi293 cells),12 and uPA (urokinase medac) was measured in the presence of TXA and EACA (0-125 mM) in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, and 0.01% Tween-80 at 450 nm, as previously described.21 IC50 derived from the linear absorbance range and Ki are summarized in supplemental Table 1. The Michaelis-Menten constant (Km) and the apparent Km values for uPA in the presence of 0 to 15 mM TXA were also determined with 0 to 0.5 mM S-2444, and data were plotted using GraphPad Prism 7.0 to calculate Ki (supplemental Figure 1; supplemental Table 1). (B) The residual clot lysis activity (reciprocal plot of the normalized 50% clot lysis time in supplemental Figure 4) was recorded in the presence of 1 μM Plm, 1 μM Plg plus tPA, or 1 μM Plg plus uPA at the concentrations indicated. Each reaction consists of a 100-μL fibrin clot preformed by incubating human fibrinogen (12.5 μM; Enzyme Research Laboratories) and thrombin (55 nM; Diagnostic Reagents) in a lysis buffer (40 mM Tris, 75 mM NaCl, 3 mM CaCl2, 0.01% Tween-20) at 37°C for 3 hours. An additional 100 μL of lysis buffer containing Plm or Plg plus tPA/uPA in the presence of 0 to 25 mM TXA was added to start the lysis; the progress of clot lysis was monitored using a nephelometer (BMG LABTECH), which records every minute for 5.5 hours at 37°C. Fifty percent clot lysis time was determined using an online application (https://drclongstaff.shinyapps.io/clotlysisCL/).22 (C) During fibrin clot lysis, Plm and uPA enzyme activities were also measured in the presence of TXA (0-50 mM), Plm substrate (H-Ala-Phe-Lys-AMC; Bachem), or uPA substrate (Glutaryl-Gly-Arg-AMC; Sekisui Diagnostics) in 100 μL of lysis buffer, as described in panel B. Enzyme activity was recorded using a FLUOstar Omega (BMG) at 37°C; excitation and emission were 355 nm and 460 nm, respectively. All data points represent the mean ± standard deviation of a minimum of 3 independent experiments. (D) Cocrystal structure of uPA and TXA. uPASP (serine protease domain of human uPA, residue 164-431) was expressed and purified from Expi293 cells, as previously described.12 uPASP was activated to the 2-chain form (tc-uPASP) by Plm (Haematologic Technologies), concentrated to 10 mg/mL, and mixed with 20 mM TXA for crystallization trials. Crystals were obtained in the presence of 0.03 M NaNO3, 0.03 M Na2HPO4, 0.03 M (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 M Tris-bicine pH 8.5, 25% (weight-to-volume ratio) polyethylene glycol monomethyl ether 500, and 10% (weight-to-volume ratio) polyethylene glycol 20 000 at 20°C. The electrostatic surface representation of uPA (basic, blue; acidic, red) is shown, with key binding residues (cyan sticks) to TXA (green sticks) labeled. There are 4 binary complex molecules in the asymmetric unit, and the model of monomer A with TXA is shown. Data collection and processing were performed as previously described (supplemental Table 2).12 Further information is shown in supplemental Figure 5.

Next, we tested whether TXA inhibits uPA-mediated Plg activation. As shown in supplemental Figure 2, TXA inhibits uPA-mediated activation of the catalytic domain of Plg (microplasminogen) in a dose-dependent manner (IC50, 4.53 ± 0.66 mM), whereas the IC50 of EACA is 26.84 ± 0.67 mM (supplemental Table 1).

We further investigated stable clot lysis in the presence of TXA, using Plm or Plm generated in situ from Plg by uPA or Plg on preformed fibrin clots. As shown in Figure 1B, supplemental Figure 4, and supplemental Table 1, the clot lysis activity is inhibited in a dose-dependent manner. No significant difference was observed using Plm, Plg plus 2 concentrations of tPA (70 nM and 350 nM) or uPA (100 U and 400 U), suggesting that the TXA inhibition is insensitive to the type or concentration of Plg activator in this experimental condition.

We next measured uPA and Plm enzyme activities during clot lysis (Figure 1C). Here, TXA inhibits uPA activity (IC50, 2.70 ± 0.11 mM). The impact of TXA on Plm activity (generated by uPA) is biphasic: it enhanced Plm activity at a concentration of 0 to 1 mM TXA and plateaued at ∼1 mM TXA (>300% activity of 0 mM TXA); a further increase in TXA concentration inhibits Plm activity. This biphasic effect on Plg is also observed in solution assay, and enhancement of activity also plateaus at ∼1 mM TXA (supplemental Figure 3). The initial stimulation of Plm activity is due to binding of TXA to the LBS of Plg, which results in a conformational change and higher activation rate; thus, it cancels out the inhibitory effect of TXA on uPA.

To characterize the TXA binding site on uPA, we performed cocrystallization experiments on the catalytic domain of uPA in the presence of TXA (Figure 1D). The structure was determined to 2.3 Å resolution and contains 4 uPA–TXA complexes in the asymmetric unit (space group P1211) (supplemental Figure 5A). All 4 TXA molecules are buried deep in the catalytic pockets. Superposition of the 4 TXA molecules in the structure shows slight movements, suggesting that they are not tightly constrained. However, all of the TXA molecules are positioned at an equivalent site in uPA to the TXA moiety of the small molecule inhibitor PSI-112 bound to the Plm active site (supplemental Figure 6).12

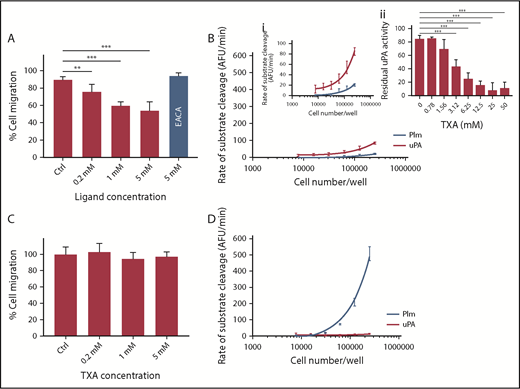

We next investigated whether TXA inhibits uPA functions independent of Plg activation/fibrinolysis using a Transwell migration assay and MDA-MB-231 BAG human breast cancer cells, which express high levels of uPAR, uPA, and PAI-113,14 As shown in Figure 2A, there is a significant and dose-dependent inhibition of cell migration, showing 26% ± 8.4% inhibition (P < .005) at 0.2 mM TXA. The impact of TXA on cell-migration plateaus at 1 mM (40% ± 4.2% inhibition, P < .0005), with no further reduction being observed up to 5 mM TXA. Conversely, no inhibition is observed at 5 mM EACA. An MTT assay was performed and has ruled out any possible impact of TXA on cell viability (supplemental Figure 7). Interestingly, similar inhibition was not observed when OVMZ6 ovarian adenocarcinoma cells15 were used for these experiments (Figure 2C).

TXA inhibits cell migration of MDA-MB-231 BAG breast cancer cells in vitro. Two cell lines were studied: the MDA-MB-231 BAG breast cancer cell line (A-B) and the OVMZ6 ovarian adenocarcinoma cell line (C-D). Inhibition of cell migration by TXA is observed in MDA-MB-231 BAG cells (A) but not in the OVMZ6 cell line (C). (B) Endogenous uPA and Plm activities were detected in MDA-MB-231 BAG cells (panel i is the same as panel B with a reduced scale on the y-axis for better illustration). (Bii) The endogenous uPA activity (250 000 cells per reaction) was inhibited by TXA (0-50 mM) in a dose-dependent manner. (D) No uPA activity was recorded in OVMZ6 cells, but a high level of Plm activity (∼30 times that of MDA-MB-231 BAG cells) was recorded. The Transwell cell-migration assay was performed by incubation of cells with TXA at 0, 0.2, 1, and 5 mM or with EACA at 5 mM for 30 minutes,23 after which migration was allowed to occur at 37°C for 3 hours. Cells were stained with a Quick Dip staining kit (Fronine) and imaged with an Olympus IX71 microscope at ×200 magnification. Migrated cell numbers were counted and averaged from 10 individual microscopic frames in duplicate conditions and plotted as a percentage of 0 mM TXA. Endogenous Plm and uPA activity was measured (as for Figure 1A) using fluorogenic substrates (as for Figure 1C) on a range of cell number inputs. All data points represent the mean ± standard deviation of ≥3 independent experiments. Both cell lines were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (50 U/mL), and streptomycin (50 μg/mL). **P < .005, ***P < .0005, 1-way analysis of variance using GraphPad Prism. AFU, arbitrary fluorescence units.

TXA inhibits cell migration of MDA-MB-231 BAG breast cancer cells in vitro. Two cell lines were studied: the MDA-MB-231 BAG breast cancer cell line (A-B) and the OVMZ6 ovarian adenocarcinoma cell line (C-D). Inhibition of cell migration by TXA is observed in MDA-MB-231 BAG cells (A) but not in the OVMZ6 cell line (C). (B) Endogenous uPA and Plm activities were detected in MDA-MB-231 BAG cells (panel i is the same as panel B with a reduced scale on the y-axis for better illustration). (Bii) The endogenous uPA activity (250 000 cells per reaction) was inhibited by TXA (0-50 mM) in a dose-dependent manner. (D) No uPA activity was recorded in OVMZ6 cells, but a high level of Plm activity (∼30 times that of MDA-MB-231 BAG cells) was recorded. The Transwell cell-migration assay was performed by incubation of cells with TXA at 0, 0.2, 1, and 5 mM or with EACA at 5 mM for 30 minutes,23 after which migration was allowed to occur at 37°C for 3 hours. Cells were stained with a Quick Dip staining kit (Fronine) and imaged with an Olympus IX71 microscope at ×200 magnification. Migrated cell numbers were counted and averaged from 10 individual microscopic frames in duplicate conditions and plotted as a percentage of 0 mM TXA. Endogenous Plm and uPA activity was measured (as for Figure 1A) using fluorogenic substrates (as for Figure 1C) on a range of cell number inputs. All data points represent the mean ± standard deviation of ≥3 independent experiments. Both cell lines were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (50 U/mL), and streptomycin (50 μg/mL). **P < .005, ***P < .0005, 1-way analysis of variance using GraphPad Prism. AFU, arbitrary fluorescence units.

We also tested endogenous enzyme activity on these cells. MDA-MB-231 BAG cells show Plm and uPA activities and, here, uPA activity is inhibited by TXA (IC50, 2.87 ± 0.37 mM, Figure 2B). In contrast, OVMZ6 cells show no uPA activity but very high Plm activity (∼30-fold higher than that of MDA-MB-231 BAG cells, Figure 2D). Finally, to study whether Plm may also play a direct role in cell migration, we tested the migration of MDA-MB-231 BAG cells in the presence of 2 Plm inhibitors: D-Val-Phe-Lys chloromethyl ketone and aprotinin.16 As shown in supplemental Figure 8, they do not inhibit cell migration. Taken together, these data suggest that TXA, at a low concentration (0.2 mM), attenuates MDA-MB-231 BAG cell migration, and it may act via inhibition of uPA on the cell surface.

Our data illustrate that TXA is a uPA inhibitor. In comparison with EACA, TXA inhibition of uPA is approximately sixfold higher. TXA is often used at a submicromolar range and, therefore, its inhibitory activity with respect to uPA is not expected to impact upon standard patient care.6 However, in cases in which a large volume of blood has been lost, and if the clearance of TXA via the kidneys is impaired, the plasma level of TXA may be substantially higher. Indeed, in cardiac surgeries, TXA levels of up to 200 μM can be measured in the cerebral spinal fluid and levels of up to 2 mM can be measured in the serum.17 Therefore, at a Ki of 2 mM, TXA may impose a block on uPA function.

Within the fibrinolytic system, TXA inhibits clot lysis by Plm generated by uPA and tPA (Figure 1B), even at high concentrations of the plasminogen activators. Accordingly, TXA is efficacious for bleeding disorders in patients with Quebec platelet disorder (a condition caused by increased expression and storage of uPA by megakaryocytes).18 However, TXA at submicromolar concentrations increases Plm activity/Plg activation by uPA (Figure 1C; supplemental Figure 3),3 which promotes fibrinogen degradation (supplemental Figure 9).19 It is foreseeable that this would prohibit stable clot formation at a time when the coagulation system is in “crisis mode.”19,20 Accordingly, our data further support the notion that, although TXA is an effective antifibrinolytic agent on preformed clots, its late administration in coincidence with high plasma uPA levels may exacerbate the depletion of hemostatic factors, such as fibrinogen and inhibit stable clot formation.10,11,19

Lastly, uPA plays many physiological roles, including wound healing and cell migration.21 Our observation that cell migration of uPA-expressing MDA-MB-231 BAG cells is sensitive to TXA, but that of non–uPA-expressing OVMZ6 cells is not, could be a result of uPA inhibition. In this regard, and outside the context of Plm and the fibrinolytic system, submicromolar TXA concentrations may impact uPA function and cell migration. The clinical implications of these findings need to be investigated further.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors of the uPA–TXA complex reported in this article have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (code 6NMB).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Viktor Magdolen (Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany) for kindly providing the OVMZ cell lines for the cell-migration assay, Australian Synchrotron, Australia's Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation, for MX2 beamtime, the use of Australian Cancer Research Foundation detector and technical assistance, and the Monash Molecular Crystallization Facility for setting up crystallization experiments.

This work was supported in part by the Australian National Health Medical Research Council. G.W. and B.A.M. are supported by Monash University PhD scholarships, and J.C.W. is a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Senior Principal Research Fellow (grant APP1127593).

Authorship

Contributions: G.W. and B.A.M. designed and conducted the study and cowrote the manuscript; M.J.V., A.J.Q., L.M.O., and P.J.C. provided input on the design of experiments and performed experiments; T.T.C.-D., J.G.S., and K.L.T. provided input on data interpretation; R.H.P.L. designed the study, provided input on data interpretation, and cowrote the manuscript; and J.C.W. provided input on data interpretation and cowrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ruby H. P. Law, Biomedicine Discovery Institute and Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC 3800, Australia; e-mail: ruby.law@monash.edu; and James C. Whisstock, Biomedicine Discovery Institute and Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC 3800, Australia; e-mail: james.whisstock@monash.edu.

References

Author notes

G.W. and B.A.M. contributed equally to this work and are joint first authors.

J.C.W. and R.H.P.L. contributed equally to this work.