Key Points

Nbeal2 deficiency leads to significantly reduced lung and brain pathology and enhanced survival in a mouse model of malaria.

Both antibody-dependent and antibody-independent platelet depletion in mice recapitulate the findings observed in Nbeal2−/− mice.

Introduction

Cerebral malaria and malaria-associated acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome are among the most severe complications of Plasmodium infection. While these disease manifestations are multifactorial, platelets have been described to play a role in the development of both syndromes in humans1,2 and mice.3,4 Although the impact of platelets on malaria has been well studied, questions remain with regard to their contribution to parasite control and immunopathogenesis. Studies have indicated that platelets can kill Plasmodium-infected red blood cells (iRBCs).5-8 However, there are contrasting reports that platelets do not exert any significant control over parasite growth but rather exacerbate malaria immunopathology.3,9-12 In this study, we address the role of platelets in the development of severe malaria in 3 different mouse models of platelet dysfunction/depletion. We show a key role for platelets, particularly platelet α-granules, in mediating organ-specific pathologies during rodent Plasmodium infection.

Methods

Rodent Plasmodium infection

Female C57BL/6J mice aged 6 to 12 weeks were bred in-house or purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Homozygous Nbeal2−/− mice on a C57BL/6J background originated from the Di Paola laboratory and were obtained by Robert Campbell to be bred in-house. C57BL/6-Tg(PF4-icre)Q3Rsko/J mice (platelet factor 4 [PF4] Cre, Stock 008535) and C57BL/6-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(HBEGF)Awai/J mice (B6-iDTR, stock 007900) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Homozygous B6-iDTR mice were bred with PF4-Cre positive or negative mice to generate PF4-Cre–positive inducible diphtheria toxin receptor (iDTR)–positive and PF4-Cre–negative iDTR-negative mice. Infections were initiated intraperitoneally with 0.5 × 106Plasmodium berghei ANKA (PbA) iRBCs (clone15cy1, 1037cl1 WT-GFP-Lucschiz; mutant RMgm-32, or a constitutive GFP-expressing clone) obtained from donor C57BL/6J mice. Peripheral parasitemia was monitored by counting 300 to 500 red blood cells (RBCs) on Diff-Quik (Siemens)–stained thin blood smears. All experiments were carried out according to protocols approved by the institutional animal care and use committees and biosafety committees of Emory University (DAR-2000454-021114BN, HAD01-2425-11R15-101915) and the University of Utah (17-01001, 05-17).

Tissue preparation for flow cytometry

Spleens were pressed through a 40-μm cell strainer and suspended in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM) containing 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 1 μM l-glutamine, 12 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, 0.5 mM sodium pyruvate, and 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol (all Gibco) (cIMDM). Single-cell suspensions of splenocytes were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 8 minutes at 4°C prior to RBC lysis of the pellet using an RBC lysis buffer (BioLegend). Splenocytes were centrifuged again before resuspension in cIMDM with the addition of 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (HI-FCS) (PAA Laboratories) for downstream flow cytometric analysis. Brains were pressed through a 100-μm cell strainer and resuspended in a 30% Percoll solution before overlaying onto a 70% Percoll gradient. Brain samples were centrifuged at 600g for 20 minutes at room temperature with no brake. The peripheral blood mononuclear cell interface was collected and washed with cIMDM + HI-FCS before resuspension in cIMDM + HI-FCS for downstream flow cytometric analysis. Lungs were placed in a 6-well plate and minced with scissors prior to incubation in digestion media (RPMI + collagenase D [Roche] + DNase [Invitrogen]) at 37°C for 30 minutes in a shaking incubator. Cells were filtered through a 100-μm cell strainer and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 8 minutes at 4°C. The pellet was then resuspended in a 40% Percoll solution before overlaying onto an 80% Percoll gradient. Lung samples were centrifuged at 1600 rpm for 25 minutes at room temperature with no brake. The interface was collected and washed prior to RBC lysis and resuspension in cIMDM + HI-FCS for downstream flow cytometric analysis.

Flow cytometry staining

Whole blood (5 μL) was collected into Krebs saline containing antibodies of interest for staining. Platelet depletion efficacy was determined by size and granularity and CD41 expression (phycoerythrin [PE], Pacific Blue, or BV421, cl. MWReg30) via flow cytometry. For time-course experiments monitoring platelet-iRBC aggregation and platelet activation, the following additional antibodies were used: TER-119 (APC/Cy7 or BV786, cl. TER-119), CD62P/P-selectin (PE or PE/Cy7, cl. RMP-1), CD63 (APC, cl. NVG-2) (all from BioLegend), and αIIbβ3 (PE, cl. JON/A) (EmFret). A PbA clone expressing constitutive GFP (PbA-GFP) was used for infections in which parasites were detected via flow cytometry. For neutrophil sequestration experiments, the following antibodies were used: Ly-6G (PE, cl. 1A8), CD11b (BV605, cl. M1/70), CD19 (BV510, cl. 6D5), Ly-6C (PerCP/Cy5.5, cl. HK1.4), and Zombie NIR viability dye (all from BioLegend).

Imaging flow cytometry

Experiments were performed on an ImageStreamX Mk II imaging flow cytometer with INSPIRE acquisition software (Amnis), which allows for distinguishing coincident vs contact events. All images were captured with the 60× objective. Whole blood (5 μL) was collected into Krebs saline containing antibodies of interest for staining. The following antibodies were used: CD41-BV421 (cl. MWReg30, to identify platelets) and TER-119-AF647 (cl. TER-119, to identify red blood cells) (both from BioLegend), in addition to the PbA-GFP fluorescent parasite to identify infected red blood cells. BV421 was excited by the 405-nm laser and emission captured in the range 435 to 505 nm (Ch1), GFP was excited by the 488-nm laser and emission captured in the range 505 to 560 nm (Ch2), AF647 was excited by the 642-nm laser and emission captured in the range 642 to 745 nm (Ch5), and bright field was captured in Ch3. Single-stained controls were used to generate a compensation matrix. IDEAS v6.2 software (Amnis) was used for data analysis on compensated data.

ELISA

Mouse PF4, elastase, and myeloperoxidase enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (all from R&D Systems) were used to detect these molecules in plasma of mice according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Bioluminescent parasite imaging

Parasite burden in tissues was determined using an IVIS Spectrum Bioluminescent Imaging System (PerkinElmer). At days 2, 4, or 6 after infection with the PbA schizont-specific luciferase reporter line, mice were injected with 150 μL RediJect D-Luciferin bioluminescent substrate (PerkinElmer) 30 minutes prior to euthanization, organ dissection, and imaging. Regions of intensity were quantified using IVIS Living Image software.

In vivo platelet/megakaryocyte depletion

C57BL/6J mice were intraperitoneally injected with 0.1 mg purified anti-mouse CD41 antibody (clone MWReg30, BioLegend) or isotype control antibody (rat immunoglobulin G1, κ, BioLegend) 1 day after infection with PbA. PF4-Cre–positive iDTR-positive ((−) MK) mice and PF4-Cre–negative iDTR-negative ((+) MK) mice were intraperitoneally injected with 20 ng diphtheria toxin (Sigma) on days −7, −4, and −1 prior to infection with PbA.

In vivo Evans blue permeability assay

Mice were injected IV with 200 μL of 1% Evans blue (Sigma) on day 6 after infection with PbA and euthanized 1 hour later. Brains and lungs were removed and imaged using a MicroCapture digital microscope (Veho) and placed into vials containing 1 mL formamide (Sigma) at 37°C for 4 days. The concentration of the dye extracted from the tissues was measured at an absorbance of 620 nm using a plate reader (Biotek).

Results and discussion

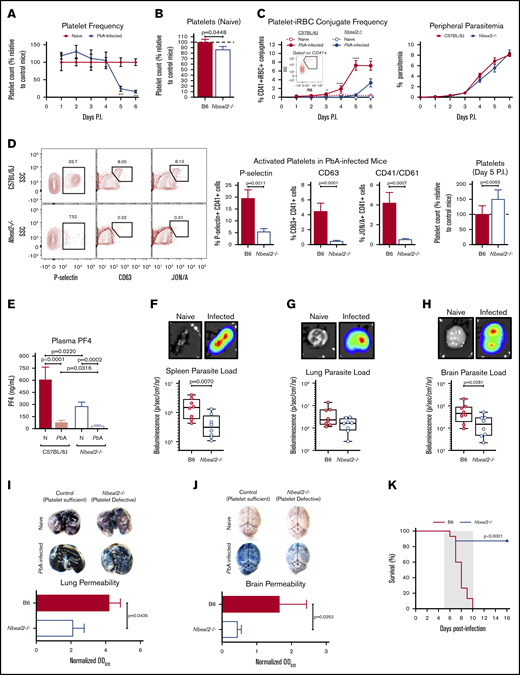

Previous studies in mice have demonstrated the importance of platelets in the development of severe malaria pathology even as platelet counts decrease significantly over the course of Plasmodium infection,9 which is a phenomenon we also observed (Figure 1A). In order to investigate how platelets and platelet α-granules may function to mediate severe malaria pathogenesis, we used PbA, a parasite strain that causes a well-established mouse model of experimental cerebral malaria (ECM)13 and lung injury,14,15 to infect wild-type C57BL/6J mice along with neurobeachin-like 2 (Nbeal2)–deficient mice, which have severe defects in platelet α-granule formation.16,17 Naive Nbeal2−/− mice had a slight but significant reduction in platelets compared with naive control mice (Figure 1B). Upon infection with PbA, we observed a significantly lower frequency of platelet-iRBC conjugates in whole blood isolated from Nbeal2−/− mice compared with C57BL/6J mice (Figure 1C, left), even though there were no significant differences in peripheral parasitemia between the 2 groups over the course of infection (Figure 1C, right). Additionally, we confirmed using imaging flow cytometry that >90% of platelet-iRBC double-positive events indeed represented platelets in contact with iRBCs (supplemental Figure 1). While we cannot conclusively determine whether platelets become activated subsequent to contact with iRBCs or if activated platelets preferentially bind to iRBCs, these data indicate that platelet α-granules can impact the ability of platelets to interact with iRBCs. However, this interaction between platelets and iRBCs has no effect on overall peripheral parasite growth, which supports previous findings.9

Nbeal2 deficiency significantly alters parasite sequestration, lung and brain pathology, and survival in PbA-infected mice. (A) Time course of platelets in peripheral blood of C57BL/6J mice after PbA infection compared with naive control mice (n = 7-10 mice/group) as determined by flow cytometry. (B) Platelets in whole blood of naive Nbeal2−/− mice normalized to naive C57BL/6J (B6) control mice as determined by flow cytometry (n = 20-24 mice/group). (C) Frequency of platelet-iRBC conjugates (left, n = 10-20 mice/group) in whole blood of C57BL/6J and Nbeal2−/− mice after PbA-GFP infection and time course of peripheral parasitemia as determined by staining and counting of thin blood smears (right, n = 10 mice/group). (D) Representative flow cytometry plots and quantification of the frequency of P-selectin+, CD63+, and CD41/CD61+ platelets as well as total platelets normalized to control mice in whole blood isolated from C57BL/6J (B6) and Nbeal2−/− mice at day 5 after infection with PbA (n = 10-26 mice/group). (E) Quantification of PF4 in the plasma of C57BL/6J and Nbeal2−/− mice at day 6 after infection with PbA (n = 10-14 mice/group) or naive (N) (n = 9-10 mice/group) as determined by ELISA. (F-H) Representative images and bioluminescence quantification of sequestered PbA schizonts expressing luciferase under the AMA-1 promoter in spleens (F), lungs (G), and brains (H) of PbA-infected C57BL/6J (B6) and Nbeal2−/− mice (n = 8 mice/group). Values are normalized to naive control mice from each respective group (n = 4 mice/group). (I-J) Lung permeability (I) and brain permeability (J) in C57BL/6J (B6) and Nbeal2−/− mice injected IV with 200 μL of 1% Evans blue dye at day 6 after infection with PbA (n = 9-13/group). Representative images and quantification of dye extracted from whole organs are shown. Optical density values are normalized to naive control mice from each respective group (n = 4 mice/group). (K) Survival curves of PbA-infected Nbeal2−/− (blue line) and C57BL/6J (B6, red line) mice (n = 15-16 mice/group). The gray shaded region represents the typical timeframe of death from ECM. Graphs in panels A-E and I-J represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. Boxes in panels F-H represent the median ± the 25th and 75th percentiles with minimum/maximum whiskers. Statistical analyses were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test (A-J) and log-rank Mantel-Cox test (K). Only statistically significant (P < .05) values are shown. For graphs in panels A and C, *P < .05, **P < .005, ***P < .0005, and ****P < .0001. Figures represent combined data from 2 (A; C, right; D, middle and right graphs; and E-J) or ≥3 (B; C, left; D, left; and K) independent experiments. P.I., postinfection; SSC, side scatter.

Nbeal2 deficiency significantly alters parasite sequestration, lung and brain pathology, and survival in PbA-infected mice. (A) Time course of platelets in peripheral blood of C57BL/6J mice after PbA infection compared with naive control mice (n = 7-10 mice/group) as determined by flow cytometry. (B) Platelets in whole blood of naive Nbeal2−/− mice normalized to naive C57BL/6J (B6) control mice as determined by flow cytometry (n = 20-24 mice/group). (C) Frequency of platelet-iRBC conjugates (left, n = 10-20 mice/group) in whole blood of C57BL/6J and Nbeal2−/− mice after PbA-GFP infection and time course of peripheral parasitemia as determined by staining and counting of thin blood smears (right, n = 10 mice/group). (D) Representative flow cytometry plots and quantification of the frequency of P-selectin+, CD63+, and CD41/CD61+ platelets as well as total platelets normalized to control mice in whole blood isolated from C57BL/6J (B6) and Nbeal2−/− mice at day 5 after infection with PbA (n = 10-26 mice/group). (E) Quantification of PF4 in the plasma of C57BL/6J and Nbeal2−/− mice at day 6 after infection with PbA (n = 10-14 mice/group) or naive (N) (n = 9-10 mice/group) as determined by ELISA. (F-H) Representative images and bioluminescence quantification of sequestered PbA schizonts expressing luciferase under the AMA-1 promoter in spleens (F), lungs (G), and brains (H) of PbA-infected C57BL/6J (B6) and Nbeal2−/− mice (n = 8 mice/group). Values are normalized to naive control mice from each respective group (n = 4 mice/group). (I-J) Lung permeability (I) and brain permeability (J) in C57BL/6J (B6) and Nbeal2−/− mice injected IV with 200 μL of 1% Evans blue dye at day 6 after infection with PbA (n = 9-13/group). Representative images and quantification of dye extracted from whole organs are shown. Optical density values are normalized to naive control mice from each respective group (n = 4 mice/group). (K) Survival curves of PbA-infected Nbeal2−/− (blue line) and C57BL/6J (B6, red line) mice (n = 15-16 mice/group). The gray shaded region represents the typical timeframe of death from ECM. Graphs in panels A-E and I-J represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. Boxes in panels F-H represent the median ± the 25th and 75th percentiles with minimum/maximum whiskers. Statistical analyses were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test (A-J) and log-rank Mantel-Cox test (K). Only statistically significant (P < .05) values are shown. For graphs in panels A and C, *P < .05, **P < .005, ***P < .0005, and ****P < .0001. Figures represent combined data from 2 (A; C, right; D, middle and right graphs; and E-J) or ≥3 (B; C, left; D, left; and K) independent experiments. P.I., postinfection; SSC, side scatter.

P-selectin (CD62P) is present within platelet α-granules and is externalized upon platelet activation. Five days after PbA infection, we observed a lower frequency of P-selectin+ platelets in blood from Nbeal2−/− mice compared with control mice as expected (Figure 1D, left graph). To determine more broadly if Nbeal2 deficiency affected overall platelet activation, we analyzed surface expression of 2 α-granule–independent markers of platelet activation: CD63, which is present in dense granules and lysosomes and externalized upon platelet activation,18 and the high-affinity conformation of the integrin αIIbβ3 (CD41/CD61).19 Similar to our findings with P-selectin, we observed a significantly lower frequency of CD63+ and CD41/CD61+ platelets isolated from Nbeal2−/− mice at day 5 after PbA infection compared with control mice (Figure 1D, middle graphs) despite Nbeal2−/− mice containing more platelets at this time point (Figure 1D, right graph). The dysfunctional platelet α-granule secretion in Nbeal2−/− mice was further validated by the presence of significantly lower concentrations of PF4 in Nbeal2−/− plasma compared with C57BL/6J control plasma both in naive mice and in mice at day 6 after infection with PbA (Figure 1E). Of note, PbA-infected mice have significantly less plasma PF4 than naive mice given the significant reduction in the platelet count that occurs by day 6 after infection (Figure 1A). Taken together, these data suggest that Nbeal2 deficiency affects platelet activation as a whole in the context of severe malaria, which may subsequently influence the ability of Nbeal2−/− platelets to interact with iRBCs.

Although we found that platelet α-granules do not inhibit PbA blood-stage parasite growth (Figure 1C, right), peripheral parasitemia does not reflect the quantity of iRBCs, specifically schizonts, that have sequestered in the microvasculature of organs. Therefore, we quantified iRBC sequestration in key organs of Nbeal2−/− mice as measured by bioluminescence of a schizont-specific luciferase-expressing PbA strain. The spleen, which is responsible for iRBC clearance and activation of the immune response against iRBCs,20 contained significantly fewer iRBCs in Nbeal2−/− mice when compared with C57BL/6J mice (Figure 1F). PbA sequestration has been associated with acute lung injury,15 yet there was no significant effect of platelet dysfunction on lung parasite sequestration in the absence of Nbeal2 (Figure 1G). However, we did observe significant differences in brain parasite sequestration which has been associated with ECM,21,22 as Nbeal2−/− mice harbored significantly fewer parasites in the brain than control mice (Figure 1H). Therefore, while platelets do not appear to alter blood-stage PbA growth, platelet α-granules can potentiate PbA organ sequestration.

PbA-induced lung and brain damage are associated with ECM,23 although the contribution of platelets to these events has not been fully elucidated. Since parasite sequestration does not always correlate with ECM development,24 we determined whether reduced parasite sequestration was accompanied by reduced pathology in these key organs. Malaria-induced vascular permeability was significantly abrogated in both the lungs (Figure 1I) and brains (Figure 1J) of Nbeal2−/− mice compared with control mice at day 6 after infection with PbA.

Strikingly, this protection from lung and brain damage correlated with nearly complete protection from ECM-associated death in Nbeal2−/− mice (Figure 1K). Thus, platelet α-granules appear to impact parasite sequestration and contribute to fatal Plasmodium-associated organ damage during ECM.

Several recent studies have described abnormalities in neutrophils and monocytes in Nbeal2−/− mice in response to different pathogenic infections.25,26 We also observed differences in neutrophil and monocyte trafficking in PbA-infected mice, with Nbeal2−/− mice harboring significantly more neutrophils and inflammatory monocytes in the spleen when compared with PbA-infected C57BL/6J control mice (supplemental Figure 2A). However, the numbers of neutrophils present in the lungs and brains of PbA-infected Nbeal2−/− and C57BL/6J mice were similar (supplemental Figure 2B-C, left graphs). PbA-infected Nbeal2−/− mice had a significantly higher frequency and number of inflammatory monocytes in their lungs compared with PbA-infected C57BL/6J control mice (supplemental Figure 2B, right graphs). Previous studies have shown that inflammatory monocytes play a key role in the clearance of organ-sequestered PbA-iRBCs that can help minimize organ damage.14 Thus, it is possible that the increase in inflammatory monocytes in the spleens of Nbeal2−/− mice could participate in reducing parasite sequestration, although this does not appear to be the case in the lungs where parasite sequestration was not significantly affected by Nbeal2 deficiency. Furthermore, Nbeal2−/− mice also experienced significantly reduced brain parasite sequestration and pathology in the absence of any difference in brain inflammatory monocyte numbers (supplemental Figure 2C, right graphs). It therefore seems unlikely that these observed differences in monocytes are responsible for the protective phenotype observed in Nbeal2−/− mice. Similarly, although neutrophils have been shown in a few studies to potentially contribute to Plasmodium-associated lung and brain damage in severe malaria,27,28 the fact that we observed no significant differences in neutrophil numbers in the lungs or brains of PbA-infected Nbeal2−/− mice compared with C57BL/6J mice also suggests that the reduced organ damage is independent of any effects of Nbeal2 deficiency on neutrophil function. In support of this, there were no significant differences in the levels of myeloperoxidase or elastase in the plasma of PbA-infected Nbeal2−/− and C57BL/6J mice at day 6 after infection (supplemental Figures 2D-E). This suggests similar systemic neutrophil activation at the onset of severe disease, even though naive Nbeal2−/− mice have significantly higher levels of both enzymes compared with naive C57BL/6J mice, as has been described previously.26

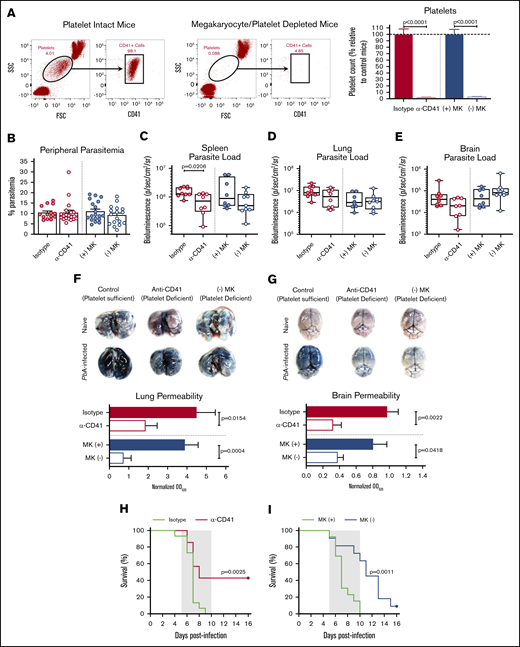

Given the clearly reduced organ pathology and enhanced survival in PbA-infected Nbeal2−/− mice, we next determined if we could recapitulate the impacts of Nbeal2 deficiency using 2 different mouse models of platelet deficiency. The first involves administering an anti-CD41 antibody to deplete platelets, which has been shown to protect against ECM.12 The second model, which has not been previously used in any Plasmodium studies, involves mice that selectively express DTR on megakaryocytes, allowing for inducible megakaryocyte depletion and reduced platelet production.29 Flow cytometry confirmed that platelets are depleted equivalently in anti-CD41 (α-CD41) and (−) MK mice (Figure 2A). As in Nbeal2−/− mice, peripheral parasite growth at day 6 after infection was unaffected by the absence of platelets (Figure 2B), further demonstrating the minimal role that platelets play in controlling PbA peripheral parasite growth. Similar to Nbeal2−/− mice, platelet-depleted mice had reduced splenic parasite accumulation (Figure 2C), although this trend was not significant in (−) MK mice. We found no significant differences in PbA parasite burden in the lungs or brains of platelet-depleted mice compared with their respective platelet-intact control groups (Figure 2D-E). Additionally, aside from a slight but significant difference in lung parasite burden at day 2 after infection, we observed no clear effects of platelet depletion on parasite sequestration at earlier time points after infection prior to day 6 (supplemental Figure 3A-C). Along with the data shown in Figure 1, these data collectively suggest a more complex role for platelets in mediating parasite trafficking and/or sequestration during PbA infection.

Platelet depletion recapitulates the reduced organ pathology and increased survival observed in Nbeal2−/−mice. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots of platelets in mouse whole blood when platelets are present (left, platelet intact mice) or absent (right, megakaryocyte/platelet–depleted mice). Platelets in whole blood of platelet-depleted anti-CD41–treated C57BL/6J mice (α-CD41) and diphtheria toxin–treated (−) MK mice normalized to their respective platelet intact control groups as quantified by flow cytometry (n = 29-37 mice/group). C57BL/6J mice were intraperitoneally injected with 100 μg of either an anti-CD41 or isotype control antibody on day 1 after PbA infection, and platelets were measured on day 3 after PbA infection. PF4-Cre–negative iDTR ((+) MK) (megakaryocyte and platelet sufficient) and (−) MK (megakaryocyte and platelet deficient) mice were intraperitoneally injected with 20 ng diphtheria toxin on days −7, −4, and −1 prior to PbA infection, and platelets were measured on day 0 of PbA infection. (B) Frequency of infected RBCs in peripheral blood of C57BL/6J mice given either an isotype control or anti-CD41 (α-CD41) antibody and diphtheria toxin–treated (+) MK and (−) MK mice at day 6 after infection with PbA as determined by staining and counting of thin blood smears (n = 14-20 mice/group). (C-E) Bioluminescence quantification of sequestered PbA schizonts expressing luciferase under the AMA-1 promoter in spleens (C), lungs (D), and brains (E) of PbA-infected mice in designated groups (n = 8-9 mice/group). Values are normalized to naïve control mice from each respective group (n = 4 mice/group). (F-G) Lung permeability (F) and brain permeability (G) in platelet-intact and depleted mice as described in panel A injected IV with 200 μL of 1% Evans blue dye at day 6 after infection with PbA (n = 7-11 mice/group). Representative images and quantification of dye extracted from whole organs are shown. Optical density values are normalized to naive control mice from each respective group (n = 4-5 mice/group). (H) Survival curves of PbA-infected C57BL/6J mice given an anti-CD41 (α-CD41, red line) or isotype control (green line) antibody on day 1 after infection (n = 15-21 mice/group). (I) Survival curves of PbA-infected (−) MK (blue line) and (+) MK (green line) mice given diphtheria toxin on days −7, −4, and −1 prior to infection (n = 11-13 mice/group). The gray shaded regions represent the typical timeframe of death from ECM. Bar graphs in panels A-B and F-G represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. Boxes in panels C-E represent the median ± the 25th and 75th percentiles with minimum/maximum whiskers. Statistical analyses were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test for isotype/α-CD41 and (+) MK/(−) MK groups, respectively (as separated by gray dotted line) (A-G) and log-rank Mantel-Cox test (H-I). Only statistically significant (P < .05) values are shown. Figures represent combined data from 2 (C-G,I) or ≥3 (A-B,H) independent experiments. FSC, forward scatter.

Platelet depletion recapitulates the reduced organ pathology and increased survival observed in Nbeal2−/−mice. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots of platelets in mouse whole blood when platelets are present (left, platelet intact mice) or absent (right, megakaryocyte/platelet–depleted mice). Platelets in whole blood of platelet-depleted anti-CD41–treated C57BL/6J mice (α-CD41) and diphtheria toxin–treated (−) MK mice normalized to their respective platelet intact control groups as quantified by flow cytometry (n = 29-37 mice/group). C57BL/6J mice were intraperitoneally injected with 100 μg of either an anti-CD41 or isotype control antibody on day 1 after PbA infection, and platelets were measured on day 3 after PbA infection. PF4-Cre–negative iDTR ((+) MK) (megakaryocyte and platelet sufficient) and (−) MK (megakaryocyte and platelet deficient) mice were intraperitoneally injected with 20 ng diphtheria toxin on days −7, −4, and −1 prior to PbA infection, and platelets were measured on day 0 of PbA infection. (B) Frequency of infected RBCs in peripheral blood of C57BL/6J mice given either an isotype control or anti-CD41 (α-CD41) antibody and diphtheria toxin–treated (+) MK and (−) MK mice at day 6 after infection with PbA as determined by staining and counting of thin blood smears (n = 14-20 mice/group). (C-E) Bioluminescence quantification of sequestered PbA schizonts expressing luciferase under the AMA-1 promoter in spleens (C), lungs (D), and brains (E) of PbA-infected mice in designated groups (n = 8-9 mice/group). Values are normalized to naïve control mice from each respective group (n = 4 mice/group). (F-G) Lung permeability (F) and brain permeability (G) in platelet-intact and depleted mice as described in panel A injected IV with 200 μL of 1% Evans blue dye at day 6 after infection with PbA (n = 7-11 mice/group). Representative images and quantification of dye extracted from whole organs are shown. Optical density values are normalized to naive control mice from each respective group (n = 4-5 mice/group). (H) Survival curves of PbA-infected C57BL/6J mice given an anti-CD41 (α-CD41, red line) or isotype control (green line) antibody on day 1 after infection (n = 15-21 mice/group). (I) Survival curves of PbA-infected (−) MK (blue line) and (+) MK (green line) mice given diphtheria toxin on days −7, −4, and −1 prior to infection (n = 11-13 mice/group). The gray shaded regions represent the typical timeframe of death from ECM. Bar graphs in panels A-B and F-G represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. Boxes in panels C-E represent the median ± the 25th and 75th percentiles with minimum/maximum whiskers. Statistical analyses were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test for isotype/α-CD41 and (+) MK/(−) MK groups, respectively (as separated by gray dotted line) (A-G) and log-rank Mantel-Cox test (H-I). Only statistically significant (P < .05) values are shown. Figures represent combined data from 2 (C-G,I) or ≥3 (A-B,H) independent experiments. FSC, forward scatter.

Despite similar parasite burdens, Plasmodium-induced vascular permeability in both the lungs (Figure 2F) and brain (Figure 2G) was significantly reduced in both models of induced thrombocytopenia. As with Nbeal2 deficiency, platelet-depleted mice also experienced significantly improved survival from ECM in both models (Figure 2H-I), although the magnitude of survival varied. This suggests that the method and timing of platelet depletion impacts ECM development.

In summary, our results show that Nbeal2−/− mice are robustly protected from the organ damage and death characteristic of PbA infection, suggesting the importance of platelet α-granules in contributing to severe malaria pathology. These effects of Nbeal2 deficiency are largely recapitulated by platelet depletion. As Nbeal2−/− mice harbor dysfunctional platelets from birth while α-CD41–treated mice and diphtheria toxin–treated (−) MK mice experience transient platelet depletion as adults, it is likely the differences among the 3 models of platelet dysfunction/depletion can potentially be attributed to the timing, magnitude, and/or mechanism of platelet depletion. The differing extents of brain parasite sequestration and survival in α-CD41 and (−) MK mice indicate that the methodology of platelet depletion itself may impact severe malaria pathology. Dysfunctional platelets in Nbeal2−/− mice may be able to recruit immune cells to sites of parasite sequestration during early PbA infection in an α-granule–independent manner30 benefitting the early response to infection. On the other hand, their lack of α-granules may render them unable to recruit pathogenic CD8 T cells to organs,31 which is required for ECM-associated pathology. Interestingly, the absence of any in vivo increase in peripheral parasitemia in any of our mouse models of platelet dysfunction/depletion contrasts with several studies that suggest platelets are a central mechanism responsible for killing iRBCs.5,32 However, those studies primarily involve nonsevere malaria models in which the kinetics of the parasite-induced inflammatory milieu likely have significant impacts on the timing of platelet activation and their subsequent response to infection. While additional research is required to continue to elucidate the complex roles of platelets in malaria, this study further supports a pathogenic role for platelets, particularly platelet α-granules, in the development of severe malaria.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Taryn Stewart and Nicole Stokes for excellent animal husbandry, the Emory University Department of Pediatrics Flow Cytometry Core and the University of Utah Health Science Center Flow Cytometry Core for flow cytometry support, Jorge Di Paola and Robert Campbell for the Nbeal2−/− mice, Josh Andersen and Daniel Call at Brigham Young University for ImageStream use and technical assistance, and Chris Janse for the luciferase-expressing and GFP-expressing PbA parasite strains.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institutes for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grant F31NS098736) (T.K.D.); National Institutes of Health, Kirschstein National Research Service Award (training grants T32AI007610 and T32AI106699) (T.K.D.); and the Institute for Cardiovascular Medicine and Research Seed Grant Fund (T.J.L.).

T.K.D. is a PhD candidate at Emory University. This work is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree.

Authorship

Contribution: T.K.D. devised and performed the experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote and edited the manuscript; M.P.S., C.C.Z., F.M.M., and P.N.M. performed the experiments; J.M.G. and S.M.J. contributed to designing the experiments; and T.J.L. devised and supervised the experiments and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Tracey J. Lamb, Department of Pathology, University of Utah, 15 North Medical Dr, Salt Lake City, UT 84112; e-mail: tracey.lamb@path.utah.edu.

References

Author notes

For data sharing, e-mail the corresponding author, Tracey J. Lamb (tracey.lamb@path.utah.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.